Introduction

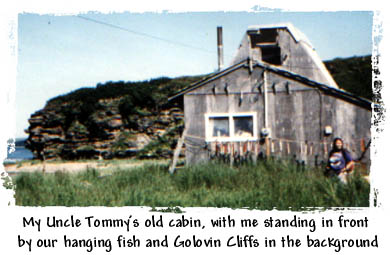

Golovin, Alaska is located in western Alaska on the Seward Penninsula.

This coastal community is located in Golovnin Bay of the Norton Sound.

You may wonder why Golovin is spelled differently from Golovnin. In 1797,

a Russian ship sailed into what is now known as Golovnin Bay; The captain

of the ship was named Golovnin, the person for which the bay was named.

The community of Golovin was changed slightly from the captain's name

because it was easier to pronounce than Golovnin. The original name of Golovin was Chinik. There

is a creek just behind Golovin, named Chinik Creek, whick still holds

the original name. One of the native corporations in Golovin, still uses

the original name, Chinik Community, Corp.

The original name of Golovin was Chinik. There

is a creek just behind Golovin, named Chinik Creek, whick still holds

the original name. One of the native corporations in Golovin, still uses

the original name, Chinik Community, Corp.

Golovin or Chinik was the original point of contact on the Seward Penninsula between white Russian sailors and the Naitve people. Many people believe that it was gold that brought a flood of outsiders into the region, but to begin with it was silver. Maggie Olson shared with me an article she found on the Omilak Mine up in the hills of the Seward Pennisula. The original outside explorers hired Eskimo men from Chinik to take them up to the mine in skin boats and kayaks. The men risked their lives and summers taking these profiteering white men to their precious mine and payed the Eskimos with only a few fish! There was even a story of an Eskimo woman who was stolen by one of the Russian sailors. When the husband of the woman protested, the sailor killed the Eskimo man.

Because Golovin was the orginal point of contact between these two radically

different cultures, I believe this clash of cultures has been very hard

on the people of Golovin.  My

grandma, Florence Willoya understands that the clash is hurting our people

and she tries to do things to help. She was the bilingual teacher for

the school for many years, and she has shared with me her collection of

papers on the Iñupiaq language. She attended many alcohol awareness

seminars to understand the pains and loses resulting from the abuse of

alcohol. She is committed to the preservation of the Iñupiaq culture

and she was thrilled to help me with this project. Maggie Olson is another

example of the Elders interacting with the youth of Golovin to see the

culture through these hard times. Maggie is a pillar of the community.

She runs church services throughout the year and opens her home to many

people. These women are true leaders in their community.

My

grandma, Florence Willoya understands that the clash is hurting our people

and she tries to do things to help. She was the bilingual teacher for

the school for many years, and she has shared with me her collection of

papers on the Iñupiaq language. She attended many alcohol awareness

seminars to understand the pains and loses resulting from the abuse of

alcohol. She is committed to the preservation of the Iñupiaq culture

and she was thrilled to help me with this project. Maggie Olson is another

example of the Elders interacting with the youth of Golovin to see the

culture through these hard times. Maggie is a pillar of the community.

She runs church services throughout the year and opens her home to many

people. These women are true leaders in their community.

The population of Golovin is about 200. Of those 200 people, I would say 15-20, approximately 5 families, use the traditional plants as a main food source and gather to save for the winter. Some plants are used by nearly everyone; for example the blueberries, salmonberries, and blackberries. The berries are collected throughout the summer and fall and put away for the winter. Most people bag the berries in ziplock and freeze them for use later in the year. This method of storage contrast the the original method of storage of berries in barrels. My grandmother has a pile of old barrels behind her house that she was planning on reviving someday. She explained how you must keep the wax on the inside intact or the barrels will leak. The barrels held many gallons of berries, or aged greens. My grandmother went on to tell me that before the barrels, our ancestors stored food in seal pokes. Pokes were made from skinned out seal skins that are blown up like ballons and dried with the hair side in. The pokes are filled with berries or greens and seal or or dried meat and seal oil and then sewn shut. My grandmother never made a seal poke, though Iím sure her father did.

Most of the people in Golovin, including the children, know which plants are used, even if the Iñupiaq names are not farmiliar to them. The biggest problem that I found is that the Iñupiaq names are being forgotten. The Elders I worked with had forgotten about 10 plant names, or the plants never had names. The names that have been forgotten are the names of plants that are not widely know and are not used as frequently as other plants.

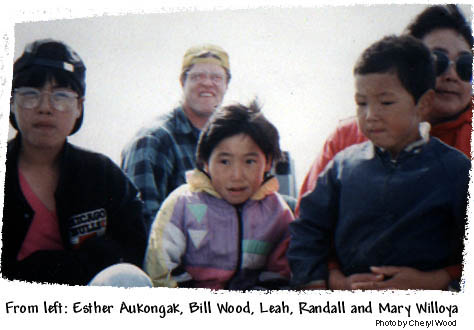

The time I spent in Golovin this summer was wonderful. As an Iñupiaq Eskimo who was raised in California, I have much to learn about my Eskimo heritage. Living in Golovin, getting to know my family and friends there, learning how to live from the land as my people have done for thousands of years was an invaluable experience I cannot express in words. I will continue to go there and I have hopes of teaching there, as well. The most valuable part of this project is that the children of Golovin came on walks with us out in to country and they were as curious as I was about the plants. I know that the work I produce from my research will reach the children and hopefully will help preserve what knowledge is available for the childrenís children and grandchildren.