|

Indigenous Knowledge Systems/Alaska Native

Ways of Knowing

by

Ray Barnhardt

Angayuqaq Oscar Kawagley

University of Alaska Fairbanks

[updated & posted online 4/29/2005]

Barnhardt, R., & Kawagley,

A. O. (2005). Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Alaska Native Ways of Knowing.

Anthropology

and Education Quarterly, 36(1), pp. 8-23.

ABSTRACT

This article seeks to extend our understanding of the

processes of learning that occur within and at the intersection of diverse

world views and knowledge

systems, drawing on experiences derived from across Fourth World contexts,

with an emphasis on the Alaska context in particular. The article outlines

the rationale behind a comprehensive program of educational initiatives

that are closely articulated with the emergence of a new generation of

indigenous

scholars who are seeking to move the role of indigenous knowledge and

learning from the margins to the center of the educational research arena and

thus

take on some of the most intractable and salient issues of our times.

A few years

ago, a group of Alaska Native elders and educators was assembled to identify

ways to more effectively utilize the traditional knowledge systems and

ways of knowing that are embedded in the Native communities to enrich

the school

curriculum and enliven the learning experiences of the students. After

listening for two days to lengthy discussions of topics such as indigenous

world views,

Native ways of knowing, cultural and intellectual property rights and

traditional ecological knowledge, an Inupiaq elder stood up and explained through

an

interpreter that he was going to describe how he and his brother were

taught to hunt caribou

by their father, before guns were commonplace in the upper Kobuk River

area of northern Alaska.

The elder described how his father had been a

highly respected hunter who always brought food home when he went out on

hunting trips and shared

it

with others

in the village. One day when he and his brother were coming of age,

their father told them to prepare to go with him to check out a herd of caribou

that was

migrating through a valley a few miles away. They eagerly assembled

their

clothing and equipment and joined their father for their first caribou

hunt. When they

reached a ridge overlooking the nearby valley, they could see a large

herd grazing and moving slowly across a grassy plain below. Their father

told

his sons to lay quietly up on the ridge and watch as he went down with

his bow

and arrows to intercept the caribou.

The boys watched as their father

proceeded to walk directly toward the caribou herd, which as he approached

began to move away from him

in a

file behind

the lead bulls, yet he just kept walking openly toward them. This

had the two brothers

scratching their heads wondering why their father was chasing the

caribou away from him. Once the father reached the area where the caribou had

been grazing,

he stopped and put his bow and arrows down on the ground. As the

(now)

elder told the story, he demonstrated how his father then got into

a crouching position and slowly began to move his arms up and down,

slapping

them against

his legs

as though he were mimicking a giant bird about to take off. The two

brothers watched intently as the lead bulls in the caribou heard

stopped and looked

back curiously at their father’s movements. Slowly at first,

the caribou began to circle back in a wide arc watching the figure

flapping

its wings

out on the tundra, and then they began running, encircling their

father in a closing

spiral until eventually they were close enough that he reached down,

picked up his bow and arrows and methodically culled out the choice

caribou one

at a time until he had what he needed. He then motioned for his sons

to come down

and help prepare the meat to be taken back to the village.

As the

elder completed the story of how he and his brother were taught the

accrued knowledge associated with hunting caribou, he explained

that in those

days the relationship between the hunter and the hunted was much

more intimate than it is now. With the intervention of modern forms

of technology,

the

knowledge associated with that symbiotic relationship is slowly being

eroded. But for

the elder, the lessons he and his brother had learned from their

father out on the tundra that day where just as vivid when he shared

them

with us as

they had been the day he learned them, and he would have little difficulty

passing

a graduation qualifying exam on the subject 70 years later. The knowledge,

skills and standards of attainment required to be a successful hunter

were self-evident, and what a young hunter needed to know and be

able to do

was both implicit and explicit in the lesson the father provided.

The insights conveyed to us by the Inupiaq elder drawing on his childhood

experience

also

have relevance to educators today as we seek ways to make education

meaningful in the 21st century. It is to explicating such relevance

that the remainder

of this article will be directed through a close examination of common

features that indigenous knowledge systems share around the world,

followed by a closer

look at some of the initiatives that are contributing to the resurgence

of Alaska Native knowledge systems and ways of knowing as a catalyst

for educational

renewal.

Indigenous peoples throughout the world have sustained their

unique worldviews and associated knowledge systems for millennia, even while

undergoing

major social upheavals as a result of transformative forces beyond

their control.

Many of the core values, beliefs and practices associated with

those worldviews have survived and are beginning to be recognized as having

an adaptive

integrity that is as valid for today’s generations as it was

for generations past. The depth of indigenous knowledge rooted

in the long inhabitation of a particular

place offers lessons that can benefit everyone, from educator to

scientist, as we search for a more satisfying and sustainable way

to live on this planet.

Actions currently being taken by indigenous

people in communities throughout the world clearly demonstrate

that a significant “paradigm shift” is

under way in which indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing are

beginning to be recognized as consisting of complex knowledge systems

with an adaptive

integrity

of their own (cf. Winter, 2004 special issue of Cultural Survival

Quarterly on indigenous education). As this shift evolves,

it is not only indigenous

people who are the beneficiaries, since the issues that are being

addressed are of equal significance in non-indigenous contexts

(Nader 1996). Many of

the problems that are manifested under conditions of marginalization

have gravitated from the periphery to the center of industrial

societies, so the

new (but old)

insights that are emerging from indigenous societies may be of

equal benefit to the broader educational community.

The tendency

in the earlier literature on indigenous education, most of which

was written from a non-indigenous perspective, was

to focus

on how

to get

Native people to acquire the appurtenances of the Western/scientific

view of the world

(Darnell 1972; Orvik and Barnhardt 1974). Until recently there

was very little literature that addressed how to get Western scientists

and educators

to

understand Native worldviews and ways of knowing as constituting

knowledge systems in

their own right, and even less on what it means for participants

when such divergent systems coexist in the same person, organization

or

community. It is imperative, therefore, that we come at these issues

on a two-way

street, rather than view them as a one-way challenge to get Native

people to buy

into

the western system. Native people may need to understand western

society, but not at the expense of what they already know and the

way they have

come to

know it. Non-Native people, too, need to recognize the co-existence

of multiple worldviews and knowledge systems, and find ways to

understand

and relate

to the world in its multiple dimensions and varied perspectives.

The intent of this article is to extend our understanding of

the processes of learning that occur within and at the intersection

of diverse world

views and knowledge systems through a comparative analysis of

experiences derived

from across multiple Fourth World contexts, drawing in particular

on our work with the Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative over the

past ten

years.

The article

will outline the rationale behind a comprehensive program of

educational initiatives that are closely articulated with the emergence of

a new generation of indigenous

scholars who are seeking to move the role of indigenous knowledge

and learning from the margins to the center of the educational

research arena and thus

take on some of the most intractable and salient issues of our

times.

Indigenous Knowledge Systems

In 2003 the U.S. Commission on Civil

Rights issued a comprehensive report titled, A Quiet Crisis: Federal

Funding and Unmet Needs

in Indian Country,

in which

the following conclusion was drawn with regard to education

of Native American students:

As a group, Native American students are

not afforded educational opportunities equal to other American

students. They routinely

face deteriorating

school facilities, underpaid teachers, weak curricula, discriminatory

treatment,

and outdated learning tools. In addition, the cultural histories

and practices of Native students are rarely incorporated

in the learning environment.

As a result, achievement gaps persist with Native American

students scoring lower

than any other racial/ethnic group in basic levels of reading,

math, and history. Native American students are also less

likely to graduate

from

high

school

and more likely to drop out in earlier grades (2003:xi).

Students

in indigenous societies around the world have, for the most part, demonstrated

a distinct lack of enthusiasm

for the

experience of schooling

in its conventional form-an aversion that is most often

attributable to an alien institutional culture, rather than any lack of

innate intelligence, ingenuity, or problem-solving skills

on the part

of

the students (Battiste

2002). The

curricula, teaching methodologies and assessment strategies

associated with

mainstream schooling are based on a worldview that does

not adequately recognize or appreciate indigenous notions of

an interdependent

universe and the importance

of place in their societies (Kawagley, Norris-Tull and

Norris-Tull 1998)

Indigenous people have had their own ways of looking at

and relating to the world, the universe, and to each other

(Ascher

2002; Eglash

2002). Their

traditional education processes were carefully constructed

around observing natural processes,

adapting modes of survival, obtaining sustenance from the

plant and animal world, and using natural materials to

make their

tools and

implements. All of this was made understandable through

demonstration and observation

accompanied

by thoughtful stories in which the lessons were imbedded

(Kawagley 1995;

Cajete 2000). However, indigenous views of the world and

approaches to education have

been brought into jeopardy with the spread of western social

structures and institutionalized forms of cultural transmission

(Barnhardt

and Kawagley 1999).

Recently, many Indigenous as well as

non-Indigenous people have begun to recognize the limitations of a mono-cultural

education

system,

and new

approaches have

begun to emerge that are contributing to our understanding

of the relationship between indigenous ways of knowing

and those

associated

with western

society and formal education. Our challenge now is to

devise a system of education

for all people that respects the epistemological and

pedagogical foundations provided by both indigenous and western cultural

traditions. While

the examples used here will be drawn primarily from the

Alaska Native context,

they are

intended to be illustrative of the issues that emerge

in any indigenous context where efforts are underway to reconnect

education to a

sense of place and

its attendant cultural practices and manifestations.

Indigenous

Knowledge and Western Science Converge

While western science and education

tend to emphasize compartmentalized knowledge which is often de-contextualized

and taught in

the detached setting of a

classroom or laboratory, indigenous people have traditionally

acquired their knowledge

through direct experience in the natural world. For

them, the particulars come to be understood in relation to

the whole,

and the “laws” are continually

tested in the context of everyday survival. Western

thought also differs from indigenous thought in its

notion of competency. In western terms, competency

is often assessed based on predetermined ideas of

what a person should know, which is then measured

indirectly

through various forms of “objective” tests.

Such an approach does not address whether that person

is actually capable of putting that knowledge into

practice. In the traditional Native sense, competency

has an unequivocal relationship to survival or extinction—if

you fail as a caribou hunter, your whole family may

be in jeopardy . You either have

it, or you don't, and it is tested in a real-world

context.

The American Association for the Advancement

of Science has begun to recognize the potential contributions

that indigenous

people

can make

to our understanding

of the world around us (Lambert 2003). In addition

to sponsoring a day-long symposium on “Native

Science” at the 2003 Annual Meeting in Denver,

AAAS has published a Handbook on Traditional

Knowledge and Intellectual Property to guide traditional knowledge

holders in protecting their intellectual property

and maintaining biological diversity (Hansen and

VanFleet 2003). In the handbook,

AAAS defines traditional knowledge as follows:

Traditional

knowledge is the information that people in a given

community, based on experience and adaptation

to

a

local culture

and environment,

have developed over time, and continue to develop.

This knowledge is used to sustain

the community and its culture and to maintain the

genetic resources necessary for the continued survival

of the

community (2003:3).

Indigenous people do a form of “science” when

they are involved in the annual cycle of subsistence

activities. They have studied and know

a great

deal about the flora and fauna, and they have their

own classification systems and versions of meteorology,

physics, chemistry, earth science, astronomy,

botany, pharmacology, psychology (knowing one's

inner world), and the sacred (Burgess 1999). For a Native

student imbued with an indigenous, experientially

grounded, holistic world view, typical approaches

to schooling can present

an impediment to learning, to the extent that they

focus on compartmentalized knowledge with little

regard for how academic subjects relate to one

another or to the surrounding universe.

To bring significance to learning

in indigenous settings,

the explanations of natural phenomena are best

understood by students

if they are

cast first in indigenous terms to which they can

relate, and then explained

in western

terms. For example, when choosing an eddy along

the river for placing a fishing net, it can be explained

initially

in the

indigenous way of understanding,

pointing out the currents, the movement of debris

and sediment in the water, the likely path of the

fish,

the condition

of the river

bank,

upstream

conditions

affecting water levels, the impact of passing boats,

etc. Once the students understand the significance

of the knowledge

being

presented,

it can

then be explained in western terms, such as flow,

velocity, resistance, turbidity,

sonar readings, tide tables, etc., to illustrate

how the modern explanation adds to the traditional

understanding

(and vice

versa). All learning

can start

with what the student and community already know

and have

experienced in everyday life. The indigenous student

(as with most students)

will then

become more

motivated to learn when the subject matter is based

on something useful and suitable to the livelihood

of the

community and

is presented

in

a way that

reflects a familiar world view (Kawagley 1995;

Lipka 1998; Battiste 2000).

Since western scientific perspectives influence

decisions that impact every aspect of indigenous people’s lives, from

education to fish and wildlife management, indigenous people themselves have

begun to take an active role

in re-asserting their own traditions of science

in various research and policy-making arenas (Arctic Environmental Protection

Strategy 1993; Cochran 2004). As

a result, there is a growing awareness of the depth

and breadth of knowledge that is extant in many indigenous societies and

its potential value in addressing

issues of contemporary significance, including

the adaptive processes associated with learning and knowledge construction.

The following observation by Bielawski

illustrates this point:

Indigenous knowledge is

not static, an unchanging artifact of a former lifeway. It has been adapting

to the contemporary

world

since contact

with “others” began,

and it will continue to change. Western science

in the North is also beginning to change in response

to contact with indigenous knowledge. Change was

first

seen in the acceptance that Inuit (and other Native

northerners) have knowledge, that is ‘know

something.’ Then change moved to involving

Inuit in the research process as it is defined

by western science. Then community-based

research began, wherein communities and native

organizations identified problems and sought the

means to solve them. I believe the next stage will

be one

in

which Inuit and other indigenous peoples grapple

with the nature of what scientists call research

(1990:8).

Such an awareness of the contemporary

significance of indigenous knowledge systems

has entered into

policy development arenas

on an international

level, as is evident in the following statement

in the

Arctic Environmental Protection

Strategy:

Resolving the various concerns that

indigenous peoples have about the development of scientific

based information

must

be addressed

through

both policy and

programs. This begins with reformulating the

principles and guidelines within which research

will be carried out and involves the process

of consultation and the development of appropriate

techniques for

identifying problems

that

indigenous peoples

wish to see resolved. But the most important

step that must be taken is to assure that indigenous

environmental and ecological

knowledge

becomes an

information system that carries its own validity

and

recognition. A large effort is now

underway in certain areas within the circumpolar

region, as well

as in other parts of the world, to establish

these information systems and

to

set standards

for their use (1993:27).

Indigenous societies,

as a matter of survival, have long sought to understand the regularities

in the

world around

them, recognizing

that nature is

underlain with many unseen patterns of order.

For example, out of

necessity, Alaska

Native people have made detailed observations

of animal behavior (including the inquisitiveness

of caribou). They have learned to decipher

and adapt to the constantly changing patterns of

weather

and

seasonal cycles.

The Native

elders have long been

able to predict weather based upon observations

of subtle signs that presage what

subsequent conditions are likely to be. The

wind, for example,

has irregularities of constantly varying velocity,

humidity, temperature, and direction

due to topography and other factors. There

are non-linear dimensions to clouds,

irregularities

of cloud formations, anomalous cloud luminosity,

and different forms

of precipitation at different elevations. Behind

these variables, however, there are patterns,

such as prevailing winds or predictable cycles

of weather phenomena that can be discerned

through long

observation

(though global

climate change

is taking

its toll on weather predictability). Over time,

Native people have observed that the weather’s

dynamic is not unlike the mathematical characteristics

of fractals, where patterns are reproduced

within themselves and the parts of a part are

part of

another part which is a part of still another

part,

and so on.

For indigenous people there is a

recognition that many unseen forces are at

play in the elements

of the universe

and that

very little

is naturally linear,

or occurs in a two-dimensional grid or a three

dimensional cube. They are

familiar with the notions of conservation of

energy,

irregularities in patterns and

anomalies of form and force. Through long observation

they have become specialists in understanding

the interconnectedness and

holism of

our place in the universe

(Barnhardt and Kawagley 1999; Cajete 2000;

Eglash 2002).

The new sciences of chaos and

complexity and the study of non-linear dynamic systems have

helped

Western scientists

to also recognize

order in phenomena

that were previously considered chaotic and

random. These patterns reveal new sets of relationships

which point

to the essential

balances and diversity

that

help nature to thrive. Indigenous people have

long recognized these interdependencies and

have

sought

to maintain harmony

with all

of life. Western scientists

have constructed the holographic image, which

lends itself to the Native concept

of everything being connected. Just as the

whole contains each part of the image, so too

does

each part contain

the makeup

of the whole.

The

relationship of each part to everything else

must be understood to produce the whole

image.

With fractal geometry, holographic images and

the sciences of chaos and complexity, the Western

thought-world

has begun

to

focus more

attention on relationships,

as its proponents recognize the interconnectedness

in all elements of

the world around us (Capra 1996; Sahtouris

2000). Thus

there is a growing appreciation

of the complementarity that exists between

what were previously considered two disparate

and

irreconcilable systems of

thought (Kawagley and

Barnhardt 2004).

The incongruities between western

institutional structures and practices and

indigenous cultural

forms will

not be easy to reconcile.

The

complexities that

come into play when two fundamentally different

worldviews converge present a formidable challenge.

The specialization,

standardization,

compartmentalization,

and systematization that are inherent features

of most western bureaucratic forms of organization

are

often

in direct conflict

with social structures

and practices in indigenous societies, which

tend toward collective decision-making, extended

kinship

structures,

ascribed authority

vested in elders, flexible

notions of time, and traditions of informality

in everyday affairs (Barnhardt 2000). It is

little wonder

then

that formal education

structures, which

often epitomize western bureaucratic forms,

have been found wanting in addressing

the educational needs of traditional societies.

When engaging in the kind of comparative analysis of different

world views outlined above, any

generalizations should

be recognized as

indicative and not definitive, since indigenous

knowledge systems are diverse

themselves and are constantly adapting and

changing in response to new conditions.

The

qualities

identified for both indigenous and western

systems represent tendencies rather than fixed

traits,

and thus must be

used cautiously to avoid

overgeneralization (Gutierrez and Rogoff 2003).

At the same time, it is the diversity and

dynamics

of indigenous societies that enrich our efforts

as we seek avenues to integrate

indigenous knowledge systems in a complementary

way with the system of education we call schooling.

Intersecting

World Views: The Alaska Experience

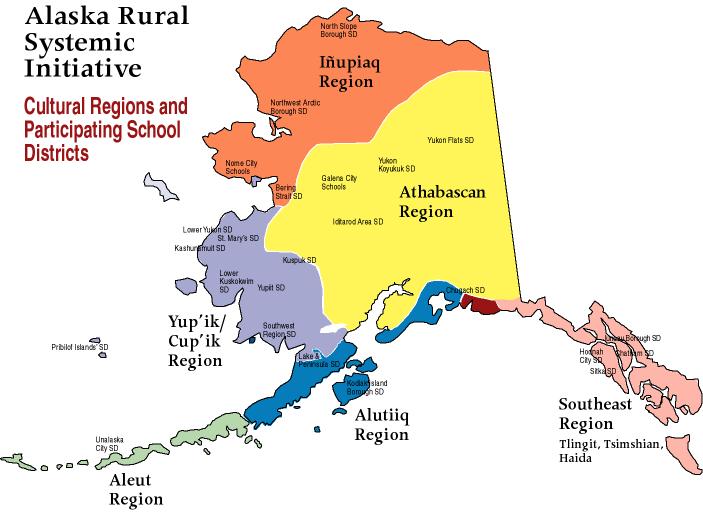

The sixteen distinct indigenous cultural

and language systems that continue to survive in

villages throughout

Alaska

have a rich cultural

history

that still governs much of everyday life in

those communities. For over six

generations, however, Alaska Native people

have been experiencing recurring negative feedback

in their relationships with the external systems

that have been brought to bear on them, the

consequences

of which

have been

extensive marginalization

of their knowledge systems and continuing erosion

of

their cultural integrity. Though diminished

and often in the

background, much

of the Native knowledge

systems, ways of knowing and world views remains

intact and in practice, and there is a growing

appreciation of the contributions

that indigenous

knowledge

can make to our contemporary understanding

in areas such as medicine,

resource management, meteorology, biology,

and in basic

human behavior and educational

practices (James 2001).

Alaska Natives have

been at the forefront in bringing indigenous perspectives into a variety

of policy

arenas through a

wide range of research and

development initiatives in recent years. In

the past two years alone, the National

Science Foundation has funded projects incorporating

indigenous knowledge in the

study of climate change, the development of

indigenous-based math curriculum, the

effects of contaminants on subsistence foods,

observations of the aurora, and alternative

technology for waste

disposal. In

addition,

Native

people have

formed new institutions of their own (e.g.,

the Consortium for Alaska Native Higher Education,

the Alaska Native

Science Commission

and

the First Alaskans

Institute) to address some of these same issues

through an indigenous lens.

Alaska Native people

have taken an active role in promoting the integration of traditional

knowledge with western

science traditions,

though

their reasons for sharing their knowledge with

outsiders

have been varied,

as indicated

by Richard Glenn, an Inupiaq who has served

on the Arctic Research Consortium and the Alaska

Native Science Commission:

Why do Iñupiat

share traditional knowledge? Despite the stigma,

our community is proud of a long history of

productive, cooperative efforts with

visiting researchers, hunters, travelers, scientists,

map makers and others. We share when we consider

others close enough to be part of Iñupiat

culture and share when it is in the best interest

of a greater cultural struggle (Glenn 2000:13–14).

In

an effort to address the issues associated

with converging knowledge systems in a more

comprehensive way and apply

new insights to address

long-standing and often intractable problems,

in1995

the University of Alaska Fairbanks,

under contract with the Alaska Federation of

Natives and with funding support from the National

Science

Foundation program,

entered into

a ten-year educational

development endeavor—the Alaska Rural

Systemic Initiative. The most critical salient

feature of the context in which this work has

been situated

is the

vast cultural and geographical diversity represented

by the sixteen distinct indigenous linguistic/cultural

groups distributed across five major geographic

regions, as the following map illustrates.

Through the Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative (AKRSI), a statewide network

of 20 partner school districts was formed, involving a total of 176 rural schools

serving nearly 20,000 predominately Alaska Native students. The remaining 28

rural school districts in Alaska (103 rural schools serving mostly non-Native

communities) have served as a comparison group for assessing the impact of

the AKRSI initiatives. Utilizing an educational reform strategy focusing on

integrating local knowledge and pedagogical practices into all aspects of the

education system, this established network of partner schools serving diverse

indigenous populations has provided a fertile real-world context in which to

address the many issues associated with learning and indigenous knowledge systems

outlined above.

The activities associated with the Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative

have been aimed at fostering connectivity and complementarity between the

indigenous knowledge systems rooted in the Native cultures that inhabit rural

Alaska and

the formal education systems that have been imported to serve the educational

needs of rural Native communities. The underlying purpose of these efforts

has been to implement a set of research-based initiatives to systematically

document the indigenous knowledge systems of Alaska Native people and to

develop pedagogical practices and school curricula that appropriately incorporate

indigenous

knowledge and ways of knowing into the formal education system. The following

initiatives have constituted the major thrusts of the AKRSI applied research

and educational development strategy (details are available at www.ankn.uaf.edu):

Indigenous

Science Knowledge Base/Multimedia Cultural Atlas Development

Native Ways of Knowing/Parent Involvement

Elders and Cultural Camps/Academy of Elders

Village Science Applications/Science Camps and Fairs

Alaska Native Knowledge Network/Cultural Resources and Web Site

Alaska Standards for Culturally Responsive Schools

Native Educator Associations/Leadership Development

Over a period of ten years,

these initiatives have served to strengthen the quality of educational experiences

and consistently improve the academic

performance of students in participating schools throughout rural Alaska

(AKRSI Annual

Report 2003). In the course of implementing the AKRSI initiatives, we

have come to recognize that there is much more to be gained from further mining

the fertile ground that exists within indigenous knowledge systems, as

well as at the intersection of converging knowledge systems and world views.

The

following diagram is intended to capture some of the critical elements

that come into play when indigenous knowledge systems and western science

traditions

are put side-by-side and nudged together in an effort to develop more

culturally

responsive science curricula (Stephens 2000).

Diagram 1

Qualities Associated with Traditional Knowledge and Western Science

In the Handbook for Culturally Responsive Science Curriculum, Sidney

Stephens explains the significance of the various components of this diagram

as follows:

For many Native educators, culturally responsive science curriculum

has to

do with their passion for making cultural knowledge, language and values a

prominent part of the schooling system. It has to do with presenting science

within the whole of cultural knowledge in a way that embodies that culture

(the Traditional Native Knowledge circle in the diagram), and with demonstrating

that science standards can be met in the process. It also has to do with finding

the knowledge, strategies and support needed to carry out this work. For those

educators not so linked to the local culture, culturally responsive science

curriculum has more to do with connecting what is known about Western science

education to what local people know and value (the Western Science circle)

(2000:10)

The implications for the learning processes imbedded in the three

domains of knowledge represented in the overlapping circles are numerous and

of considerable

significance. Stephens highlights some of the implications for how we approach

education as follows:

Although educators obviously differ in their perspective,

there is no doubt that the creation of culturally responsive science curriculum

has powerful

implications for students for at least three reasons. The first is that a student

might conceivably develop all of the common ground skills and understandings

while working from and enhancing a traditional knowledge base. The second is

that acquisition of the common ground, regardless of route, is a significant

accomplishment. And the third is that exploration of a topic through multiple

knowledge systems can only enrich perspective and create thoughtful dialog

(2000:10-11).

With these considerations in mind, the Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative

has sought to serve as a catalyst to promulgate curricular and pedagogical

reforms

focusing on increasing the level of connectivity and complementarity between

the formal education systems and the indigenous knowledge systems of the communities

in which the schools are situated. In so doing, the AKRSI has attempted to

bring the two systems together in a manner that promotes a synergistic relationship

such that the two previously disparate systems join to form a more comprehensive

holistic system that can better serve all students, not just Alaska Natives,

while at the same time preserving the essential integrity of each component

of the larger over-lapping system. The implications of such an approach to

learning as it relates to indigenous knowledge systems extend far beyond Native

communities in Alaska, as indicated by Battiste in her comprehensive literature

review on Indigenous Knowledge and Pedagogy in First Nations Education (Canada):

Indigenous

scholars discovered that indigenous knowledge is far more than the binary

opposite of western knowledge. As a concept, indigenous knowledge benchmarks

the limitations of Eurocentric theory — its methodology, evidence, and

conclusions — reconceptualizes the resilience and self-reliance of indigenous

peoples, and underscores the importance of their own philosophies, heritages,

and educational processes. Indigenous knowledge fills the ethical and knowledge

gaps in Eurocentric education, research, and scholarship (2002:5).

Examples

of what this “fresh vantage point” looks like are provided

in recently developed curriculum materials that seek to integrate western and

indigenous knowledge in a complementary way (cf. Aikenhead 2001; Adams and

Lipka 2003; Carlson 2003). Indigenous people themselves have begun to rethink

their role and seek to blend old and new practices in ways that are more likely

to fit contemporary conditions. There are ways to break out of the mindset

in which we are oftentimes stuck, though it takes some effort. There are ways

to develop linkages that connect different worldviews, at least for a few people

under the right conditions. The kinds of insights that emerge from such efforts

often open up as many questions as answers. We have learned a tremendous amount

from recent experience, and we find each year that the more we learn the less

we know, in terms of having penetrated through another layer of understanding

of what life in an indigenous context is all about, only to recognize the existence

of many additional layers that lie beyond our current understanding.

One of

the major limitations in these endeavors, however, has been the severe lack

of indigenous people with advanced indigenous expertise and western research

experience to bring balance to the indigenous knowledge/western science research

enterprise. Thus, one of the long-term goals of the AKRSI has been to develop

a sustainable research and development infrastructure that makes effective

use of the rich cultural and natural environments of indigenous peoples to

implement an array of intensive and comparative research initiatives, with

partnerships and collaborations in indigenous communities across the U.S. and

around the world. To begin to address this issue, UAF has expanded its program

offerings through a series of special seminars, distance education courses,

visiting scholars, international exchanges, internships and Indigenous Elder

Academies. In addition, a new M.A. with an emphasis on indigenous knowledge

systems has been established, with the following graduate courses now available

to students anywhere in the U.S. or Canada through the Center for Cross-Cultural

Studies distance education program:

CCS 601, Documenting Indigenous Knowledge

CCS 608, Indigenous Knowledge Systems

CCS 610, Education and Cultural Processes

CCS 611, Culture, Cognition and Knowledge Acquisition

CCS 612, Traditional Ecological Knowledge

CCS 602, Cultural and Intellectual Property Rights

The initiatives outlined

above have brought together the resources of indigenous-serving institutions

and the communities they serve to forge new configurations and

collaborations that break through the obfuscations associated with conventional

paradigms of research on cultural influences in learning. Alaska, along with

the other indigenous cultural regions of the world, provides a natural laboratory

in which indigenous and non-indigenous scholars can get first-hand experience

integrating the study of learning and indigenous knowledge systems.

There are

numerous opportunities to probe deeper into the basic issues that arise as

we explore terrain that has always been a part of our existence, but

is now being seen through new multi-dimensional lens that provide greater breadth

and depth to our understanding. Given the comprehensive nature of indigenous

knowledge systems, they provide fertile ground for pursuing a broad interdisciplinary

research agenda. In the next section we will identify some of the most promising

research opportunities that have emerged from the intersection of indigenous

knowledge systems and western educational and scientific endeavors.

Emerging

Research Associated with Indigenous Knowledge Systems

The study of indigenous

knowledge systems as it relates to education falls into three inter-related

research themes: documentation and articulation of

indigenous knowledge systems; delineating epistemological structures and learning/cognitive

processes associated with indigenous ways of knowing; and developing/assessing

educational strategies integrating indigenous and western knowledge and ways

of knowing. These issues encompass some of the most long-standing cultural,

social and political challenges facing education in indigenous societies around

the world. Public debate on these issues has revolved around apparent conflicts

between educational, political and cultural values, all of which are highly

interrelated, so it is essential that future research address the issues in

an integrated, cross-cultural and cross-disciplinary manner, and with strong

indigenous influence. Following is a brief description of some of the major

research initiatives that have emerged from the study of indigenous knowledge

systems.

Native Ways of Knowing/Indigenous Epistemologies:

Indigenous scholars have begun to identify the epistemological underpinnings

and learning processes

associated with indigenous knowledge systems (Kawagley 1995; Cajete 2000; Meyer

2001). The Venn diagram depicting the intersection of traditional Native knowledge

and western science presented earlier contains numerous topical areas in which

comparative research can be undertaken to gain a better understanding of the

inner-workings of the many and varied indigenous knowledge systems around the

world, as well as a more detailed explication of the elements of “common

ground” that emerge when the diverse knowledge systems interact with one

another. Collaboration among scholars across the indigenous cultural regions

will enhance the degree of generalizability that can be achieved as well as

facilitate the transfer of knowledge to other related sectors.

Culturally Responsive

Pedagogy/Contextual Learning: The development and implementation

of the “Alaska

Standards for Culturally Responsive Schools” and “Guidelines

for Respecting Cultural Knowledge” by the Assembly of Alaska Native Educators

(1998) has fostered a great deal of promising innovation in schools seeking

to integrate indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing into their curriculum

and pedagogical practices. While there appears to be a strong positive correlation

between the implementation of the Cultural Standards in the schools/ communities

and Native student academic performance, the details of those associations

have not yet been fully delineated. The research implications and opportunities

in this area are of considerable interest and potential consequence with regard

to how we approach schooling in general, not just in indigenous settings. Research

initiatives should engage scholars incorporating multiple research traditions

and theories associated with cultural and contextual influences on learning,

teaching and cognition. Of particular interest are the implications of current

theories associated with various forms of contextually-driven teaching and

learning (Johnson 2000).

Ethno-mathematics: Ethno-mathematics has emerged

in the last decade as a powerful blending of insights from the mathematical

sciences

and cross-cultural analysis

(Asher 2002; Eglash 2002). The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics

recently published a collection of articles under the heading, Changing

the Faces of Mathematics: Perspectives on Indigenous People of North America,

several of which reflected research from Alaska (Hankes and Fast 2002). Alaska

has

been at the forefront in the development of curriculum materials that utilize

Alaska Native constructs such as fish rack construction, egg gathering, salmon

harvesting and star navigation as an avenue for teaching mathematical content

that prepares students to meet national and state standards and related assessment

mandates (Adams and Lipka 2003). All of these recent breakthroughs in our understanding

of how mathematical knowledge is constructed and utilized provide extensive

opportunities for research on mathematics learning across cultures that has

significant implications for schooling, particularly since mathematics is one

of the critical elements in the current assessment systems associated with

No Child Left Behind.

Indigenous Language Learning: Indigenous languages

are an integral part of indigenous knowledge systems and thus warrant particular

attention in our efforts

to understand how to better integrate learning in school with the cultural

context of the home/community in indigenous societies. Research issues associated

with indigenous languages extend beyond the makeup of the language itself to

include the thought processes imbedded in the language, as well as how, when,

where and for what purposes the language is used (sociolinguistics). Only then

can we begin to understand what happens to an indigenous knowledge system when

the language associated with that system of thought is usurped by another (G.H.

Smith 2002).

Cross-Generational Learning/Role of Elders/Camps:

A dominant theme throughout

the Alaska Standards for Culturally Responsive Schools (Assembly of Alaska

Native Educators 1998) is the importance of drawing Native elders into the

educational process and utilizing natural learning environments in which the

knowledge that is being passed on to the students by the elders takes on appropriate

meaning and value and is reinforced in the larger community context. While

available data affirms the broad educational value of cross-generational learning

in culturally appropriate contexts (Johnson 2002; Battiste 2002), the dynamics

associated with such learning has not yet been well documented and translated

into comprehensive pedagogical or curricular strategies.

Place-based Education:

The importance of linking education to the physical and cultural environment

in which the student/school is situated has special

significance in indigenous settings, where people have acquired a deep and

abiding sense of place and relationship to the land in which they have lived

for millennia (Barnhardt and Kawagley 1999; Semken and Morgan 1997). “Place-based” educational

practices have received wide-spread national recognition and support as a way

to foster civic responsibility while also enriching the educational experiences

for all students—rural and urban, indigenous and non-indigenous alike

(G. Smith 2002; Gruenewald 2003; Sobel 2004). Indigenous scientific and cultural

knowledge associated with local environments is a critical ingredient for developing

an interdisciplinary pedagogy of place (Cajete 2000). As such, these systems

of knowledge offer many opportunities for comparative research into how traditional

indigenous ways of learning and knowing can be drawn upon to expand our understanding

of basic educational processes for all students.

Native Science/Sense-Making:

The ways of constructing, organizing, using, and communicating knowledge that

have been practiced by indigenous peoples for

centuries have come to be recognized as constituting a form of science with

its own integrity and validity, as indicated by a day-long AAAS-sponsored symposium

on “Native Science” at its 2003 meeting (Lambert 2003). Mainstream

science also has its distinctive ways of constructing, organizing, using and

communicating knowledge. Both Native and mainstream knowledge systems are largely

implicit, however, and while they overlap, they also diverge in ways important

to how knowledge is learned and applied. Native scholars have been actively

contributing their insights to the growing body of literature around the themes

of Native science and sense-making (Cajete 2000; James 2001; Krupnik and Jolly

2002; Hankes and Fast 2002).

Cultural Systems, Complexity and Learning: An

area of special interest in exploring the implications of indigenous knowledge

systems and the structures by which

they are perpetuated is the potential insights that can be gained from the

application of complexity theory to our understanding of the dynamics that

occur when diverse knowledge systems collide with one another (Eglash 2002;

Barnhardt and Kawagley 2003). Since this is a sufficiently broad (and complex)

arena with many convergent, divergent and emergent properties and possibilities,

it has the potential to evolve as a significant research theme that capitalizes

on the recent insights gained from the study of complex adaptive systems and

through which we can apply those insights to stimulate the development of self-organizing

structures that emerge from interactions within and between diverse knowledge

systems.

Indigenizing Research in Education: Until recently,

research traditions in education have been dominated by western science methods,

models and practices,

including those applied to indigenous peoples. In 1999, Maori scholar Linda

Tuhiwai Smith published Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous

Peoples, which articulated the importance of indigenous people devising

and using their own research methodologies and addressing issues from frames

of

reference that derive from within their own communities and cultural traditions.

Indigenous scholars are in a position to enlarge the scope of research paradigms

in ways that will benefit all research traditions.

The research topics outlined

above have the potential to advance our understanding of learning as it occurs

in diverse cultural contexts by exploring the interface

between indigenous and western knowledge systems, as well as contributing to

the further conceptualization, critique and development of indigenous knowledge

systems in their own right, drawing on the experiences of indigenous peoples

from around the world. The expansion of the knowledge base associated with

learning and indigenous knowledge systems will contribute to an emerging interdisciplinary

body of scholarly work regarding the critical role that the local cultural

context can play in fostering academic success in learning, particularly among

indigenous peoples.

Conclusion

An underlying theme of this article has been the need to reconstitute

the relationship between indigenous peoples and the immigrant societies in

which they are embedded.

By documenting the integrity of locally situated cultural knowledge and skills

and critiquing the learning processes by which such knowledge is transmitted,

acquired and utilized, Alaska Native and other indigenous people are engaging

in a form of self-determination that will not only benefit themselves, but

will open opportunities to better understand learning in all its manifestations

and thus inform educational practices for everyone’s benefit. Traditional

processes for learning to hunt caribou by observation and meaningful participation

can offer insights into how we create opportunities for students learning to

operate a computer. To overcome the long-standing estrangement between indigenous

communities and the external institutions impacting their lives, all parties

in this endeavor (community, school, higher education, state and national agencies)

will need to form a true multi-lateral partnership in which mutual respect

is accorded the contributions that each brings to the relationship. The key

to overcoming the historical imbalance in that regard is the development of

collaborative research endeavors specifically focusing on education and indigenous

knowledge systems, with primary direction coming from indigenous people so

they are able to move from a passive role subject to someone else’s agenda

to an active leadership position with explicit authority in the construction

and implementation of the research initiatives (Harrison 2001).

In this context,

the task of achieving broad-based support hinges on our ability to demonstrate

that such an undertaking has relevance and meaning in the local

indigenous contexts with which it is associated, as well as in the broader

social, political and educational arenas involved. By utilizing research

strategies that link the study of learning to the knowledge base and ways of

knowing already

established in the local community and culture, indigenous communities are

more likely to find value in what emerges and be able to put the new insights

into practice toward achieving their own ends as a meaningful exercise in

real self-determination. In turn, the knowledge gained from these efforts will

have

applicability in furthering our understanding of basic human processes associated

with learning and the transmission of knowledge in all forms.

References Cited

Adams, Barbara L. and Jerry Lipka

2003 Building a Fish Rack: Investigations into Proof, Properties, Perimeter

and

Area. Calagary, AB: Detselig Enterprises.

Aikenhead, Glen

2001 Integrating Western and Aboriginal Sciences: Cross-Cultural Science

Teaching. Research in Science Education 31(3): 337-355.

Alaska Rural Systemic

Initiative

2003 Annual Report. Fairbanks: Alaska Native Knowledge Network (ankn.uaf.edu/arsi.html),

University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy

1993 A Research Program on Indigenous Knowledge, Anchorage, AK: Inuit

Circumpolar Conference.

Ascher, Martha

2002 Mathematics Elsewhere: An Exploration of Ideas Across Cultures.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Assembly of Alaska Native

Educators

1998 Alaska Standards for Culturally Responsive Schools. Fairbanks:

Alaska Native Knowledge Network , University

of

Alaska Fairbanks.

http://ankn.uaf.edu/Publications/standards.html

Barnhardt, Ray and A. Oscar Kawagley

2004 Culture, Chaos and Complexity: Catalysts for Change in Indigenous

Education. Cultural Survival Quarterly 27(4): 59-64.

Barnhardt, Ray

2002 Domestication of the Ivory Tower: Institutional Adaptation to

Cultural Distance. Anthropology and Education Quarterly 33(2): 238-249.

Barnhardt, Ray and A. Oscar Kawagley

1999 Education Indigenous to Place: Western Science Meets Indigenous

Reality. In Ecological Education in Action. Gregory Smith and Dilafruz

Williams,

eds. Pp. 117-140. New York: State University of New York Press.

Battiste, Marie

2002 Indigenous Knowledge and Pedagogy in First Nations Education:

A Literature Review with Recommendations. Ottawa: Indian and Northern

Affairs

Canada.

Bielawski, Ellen

1990 Cross-Cultural Epistemology: Cultural Readaptation Through the

Pursuit of Knowledge. Edmonton: Department of Anthropology, University

of Alberta.

Burgess, Philip

1999 Traditional Knowledge: A Report prepared for the Arctic Council

Indigenous Peoples' Secretariat. Copenhagen: Indigenous Peoples'

Secretariat, Arctic

Council.

Cajete, Gregory

2000 Native Science: Natural Laws of Interdependence. Sante Fe, NM:

Clear Light Publishers.

Capra, Frithof

1996 The Web of LIfe: A New Scientific Understanding of Living Systems.

New York: Doubleday.

Carlson, Barbara S.

2003 Unangam Hitnisangin/Unangam Hitnisangis: Aleut Plants. Fairbanks:

Alaska Native Knowledge Network.

Cochran, Patricia

2004 What is Traditional Knowledge? Traditional Knowledge Systems

in the North. Anchorage: (http://www.nativescience.org/html/traditional_knowledge.html)

Alaska

Native Science Commission.

Darnell, Frank, ed.

1972 Education in the North: The First International Conference

on Cross-Cultural Education in the Circumpolar Nations. Fairbanks:

Center

for Northern

Education Research, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Eglash, Ron

2002 Computation, Complexity and Coding in Native American Knowledge

Systems. In Changing the Faces of Mathematics: Perspectives on

Indigenous People

of North America. Judith E. Hankes and Gerald R. Fast, eds. Pp.

251-262. Reston,

VA: National

Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

Glenn, Richard

2000 Traditional Knowledge, Environmental Assessment, and the Clash

of Two Cultures. In Handbook for Culturally

Responsive Science Curriculum. S. Stephens,

ed. Pp.

13-14. Fairbanks: Alaska Native Knowledge Network.

Gruenewald, David A.

2003 The Best of Both Worlds: A Critical Pedagogy of Place. Educational

Researcher 32(4): 3-12.

Gutierrez, Kris D. and Barbara Rogoff

2003 Cultural Ways of Learning: Individual Traits or Repertoires

of Practice. Educational Researcher 32(5): 19-25.

Hankes, Judith E. and Gerald R. Fast, eds.

2002 Changing the Faces of Mathematics: Perspectives on Indigenous

People of North America. Reston, VA: National Council of Teachers

of Mathematics.

Hansen, Stephen A. and Justin W. VanFleet

2003 Traditional Knowledge and Intellectual Property. Washington,

D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Harrison,

Barbara

2001 Collaborative Programs in Indigenous Communities. Walnut

Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

James, Keith, ed.

2001 Science and Native American Communities. Lincoln, NE:

University of Nebraska Press.

Johnson, Elaine

2002 Contextual Teaching and Learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin

Press.

Kawagley, A. Oscar, Delena Norris-Tull and Roger Norris-Tull

1998 The Indigenous Worldview of Yupiaq Culture: It's Scientific

Nature and Relevance to the Practice and Teaching of Science.

Journal of Research

in

Science Teaching

35(2): 133-144.

Kawagley, A. Oscar

1995 A Yupiaq World View: A Pathway to Ecology and Spirit.

Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press.

Krupnik, Igor and Dyanna Jolly, eds.

2001 The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic

Environmental Change. Fairbanks: Arctic Research Consortium

of the United States.

Lambert, Lori

2003 From 'Savages' to Scientists: Mainstream Science Moves Toward

Recognizing Traditional Knowledge. Tribal College Journal of

American Indian Higher

Education 15(1): 11-12.

Lipka, Jerry

1998 Transforming the Culture of Schools: Yup'ik Eskimo Examples.

Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Meyer, Manulani

A.

2001 Our Own Liberation: Reflections on Hawaiian Epistemology.

The Contemporary Pacific 13(1): 124-148.

Nader, Laura

1996 Naked Science: Anthropological Inquiries into Boundaries,

Power and Knowledge. New York, NY: Routledge.

Orvik, James,

and Ray Barnhardt, eds.

1974 Cultural Influences in Alaska Native Education. Fairbanks:

Center for Northern Education Research, University of

Alaska Fairbanks.

Sahtouris, Elisabet

2000 The Indigenous Way. In EarthDance: Living Systems

in Evolution, Elisabet Sahtouris. New York, NY: iUniversity

Press: 323-343.

Semken, Steve C. and F. Morgan

1997 Navajo Pedagogy and Earth Systems: Journal of

Geoscience Education, 45(1): 109-112.

Smith, Gregory

2002 Place-based Education. Phi Delta Kappan 84(2): 584-594.

Smith, Graham H.

2002 Kaupapa Maori Theory: An Indigenous Theory of Transformative

Praxis. Auckland, NZ: University of Auckland/Te Whare

Wananga o Awanuiarangi.

Smith, Linda T.

1999 Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous

Peoples. New York: Zed Books.

Sobel, David

2004 Place-Based Education: Connecting Classrooms and

Communities. Great Barrington, MA: The Orion Society.

Stephens,

Sidney

2000 Handbook for Culturally Responsive Science Curriculum.

Fairbanks: Alaska Native Knowledge Network.

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights

2003 A Quiet Crisis: Federal Funding and Unmet Needs

in Indian Country, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Commission

on Civil

Rights.

|