The Alaska Native Knowledge

Network

by

Ray Barnhardt

[To be published in Local

Diversity: Place-Based Education in the Global Age,

Greg Smith and David Gruenewald, eds., Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates (2005)]

This chapter will

describe a ten-year educational restoration effort aimed at bringing the

Indigenous

knowledge systems and ways of knowing that have sustained the Native people

of Alaska for millennia to the forefront in the educational systems serving

all Alaska students and communities today. The focus will be on describing

how Native people have begun to reintegrate their own knowledge systems

into the school curriculum as a basis for connecting what students learn

in school with life out of school. This process has sought to restore

a traditional sense of place while at the same time broadening and deepening

the educational experience for all students. Included will be a discussion

of the role of local Elders, cultural atlases, traditional values, cultural

camps, experiential learning, and cultural standards. All serve as

the basis for a pedagogy of place that shifts the emphasis from teaching

about local culture to teaching through the culture as students learn about

the immediate places they inhabit and their connection to the larger world

within which they will make a life for themselves.

Old Minto Cultural Camp

OUR MISSION IS TO HONOR OUR ANCESTORS

by preserving and protecting Athabascan

values, knowledge,

language, and traditions. We aim to facilitate

the passing on of

these things from elders to youth, and

to share our culture with

others in the land of our grandmothers.

We carry out these goals

in the spirit of healthy lifestyles and

education, and with respect

for ourselves, the Earth and all life.

– Cultural Heritage and Education

Institute

For nearly two

decades, the University of Alaska Fairbanks, in cooperation with the Cultural

Heritage

and Education Institute of the village of Minto, has been offering an opportunity

for university students in selected summer courses to spend a week at the

Old Minto Cultural Camp on the Tanana River under the tutelage of local

Athabascan Elders and their families. The program is designed as

a cultural immersion experience for teachers and others new to Alaska,

as well as for students entering the UAF graduate programs in cross-cultural

studies.

Participants in

the Old Minto Cultural Camp are taken 30 miles down the Tanana River from

Nenana by river

boat to the site of the former village of Minto, which was vacated in 1970

when the new village of Minto was constructed 25 miles away near the Tolovana

River on the north end of the Minto Flats. In 1984, the Elders from

Minto set up the Cultural Heritage and Education Institute as a non-profit

entity with Robert Charlie as director, to help them regain control over

the old village site and put it to use for cultural and educational purposes. In

addition to the UAF Cultural Camp, the site has been used in the ensuing

years by the Minto Elders to provide summer and winter cultural heritage

programs for the young people of Minto, as well as for others from as far

away as Anchorage, Yukon Territory, New York, England and Australia. In

addition, the Tanana Chiefs Conference (a tribal organization serving Interior

Alaska) has been using Old Minto as the site for a successful alcohol and

drug recovery camp. Despite State restrictions on the use of the

site (until title was regained by the Minto Tribal Council in 2004), participants

in the various Old Minto programs, including the UAF faculty and students,

have helped to restore several of the old buildings, clean up the cemeteries,

clear two campsites, and construct a fish-wheel, a smoke house, drying

racks, outhouses, kitchen facilities, a dining hall and ten cabins for

year-round use.

Participants in

the summer cultural immersion program spend eight days at Old Minto, arriving

in time for lunch

on Saturday and then spending the remainder of the first day "making camp," including

collecting spruce boughs for the tents and eating area, bringing in water

and firewood, and helping with the many chores that go with living in a

fish camp. Except for a few basic safety rules that are made explicit

upon arrival, everything at the camp for the remainder of the week is learned

through participation in the on-going life of the people serving as our

hosts/teachers. Volunteer work crews are assembled for the various

projects and activities that are always underway, with the Elders providing

guidance and teaching by example. Many small clusters of people — young

and old, Native and non-Native, experts and novices—can be seen throughout

the camp busily working, visiting, showing, doing, listening and learning

from each other. Teachers become students and students become teachers. At

the end of the day, people gather to sing, dance, joke, tell stories, play

games and watch the midnight sun hover over the Tanana River. On

the last evening, a potlatch is held with special foods prepared by the

camp participants and served to over 100 guests in a traditional format

on the ground adjacent to the riverbank, followed with speeches relating

the events of the week to the life and history of the area and the people

of Minto.

By the time the

boats head back upriver to Nenana on Saturday, everyone has become a part

of Old Minto—connected

to the place and the people whose ancestors are buried there. It

is an experience for which there are no textbook equivalents. What

is learned cannot be acquired vicariously, because it is embedded in the

environment and the learning experience itself, though not everyone comes

away having learned the same thing. In fact, one of the strengths

of the program is that each participant comes away having learned something

different and unique to (and about) themselves.

The Old Minto Camp

experience (which occurs during the middle week of a three-week course)

contributes

enormously to the overall level of cross-cultural understanding that students

achieve in a relatively short period of time—a level of understanding

that could not be achieved in a years worth of reading and discussion in

a campus-based seminar. Part of the reason for this is that students

come back to class during the third week with a common experience of immersion

in a culture deeply rooted in a particular place, against which they can

bounce their ideas and build new levels of understanding. More significantly,

however, students have been able to immerse themselves in a new cultural

milieu in a non-threatening and guided fashion that allows them to set

aside their own predispositions long enough to begin to see the world through

other peoples eyes. For this, most of the credit needs to go to the

Elders of Minto, who have mastered the art of making themselves accessible

to others, and to the Director, Robert Charlie, who makes it all happen. For

the Minto people, it provides an opportunity to reconnect with their own

heritage and ancestral place, and to enlist the teachers' help in experimenting

with new ways to pass on that heritage to their children and grandchildren

(as indicated in the Cultural Heritage and Education Institute mission

statement).

The greatest challenge

for those of us teaching the courses associated with the camp experience

is to help

the students/teachers find ways to transfer what they have learned at Old

Minto to their future practice as educators, while at the same time helping

them to recognize the limitations and dangers of over-extending their sense

of expertise on the basis of the small bits of cultural insights they may

have acquired on the banks of the Tanana River. By taking the teachers

to a traditional camp environment for a cultural immersion experience of

their own, our intent has been to encourage them to consider ways to use

cultural camps and Elder's expertise in their own teaching. At least

one graduate of the program has taken the experience to heart and has developed

a graduate course in "Place-based Education" into which he has

incorporated a weeks stay at Old Minto for his summer class.

Teachers, schools

and communities throughout Alaska have sponsored similar camps for a wide

variety of purposes,

but in many instances the camps are treated as a supplementary experience,

rather than as an integral part of the school curriculum. We hope

that graduates of Old Minto will lead the way in making cultural camps

and Elders the classrooms and teachers of the future in rural Alaska, which

is why "Elders and Cultural Camps" has become one of the key

initiatives that has been implemented over the past ten years through the

Alaska Rural

Systemic Initiative/Alaska Native Knowledge Network in each of the five

major cultural regions in Alaska.

Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative

In an effort to

address the issues associated with converging knowledge systems in a comprehensive

, in-depth way and apply new insights to address long-standing and seemingly

intractable problems with schooling for Native students, in 1995 the Alaska

Federation of Natives, in collaboration with the University of Alaska Fairbanks

and with funding from the National Science Foundation, entered into a long-term

educational restoration endeavor—the Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative

(AKRSI). The underlying purpose of the AKRSI has been to implement

a set of initiatives to systematically document the Indigenous knowledge

systems of Alaska Native people and develop school curricula and pedagogical

practices that appropriately incorporate local knowledge and ways of knowing

into the formal education system. The central focus of the AKRSI

strategy has been the fostering of connectivity and complementarity between

two functionally interdependent but historically disconnected and alienated

complex systems—the Indigenous knowledge systems rooted in the Native

cultures that inhabit rural Alaska, and the formal education systems that

have been imported to ostensibly serve the educational needs of Native

communities. Within each of these evolving systems is a rich body

of complementary knowledge and skills that, if properly explicated and

leveraged, can serve to strengthen the quality of educational experiences

and improve the academic performance of students throughout Alaska (Boyer

2005).

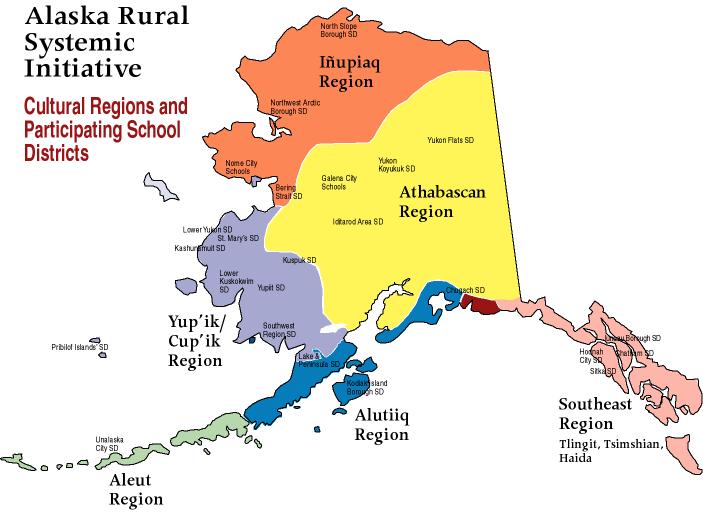

The most critical salient feature

of the context in which this work has been situated is the vast cultural

and geographical diversity represented by the sixteen distinct Indigenous

linguistic/cultural groups distributed across five major geographic regions,

as the following map illustrates.

The diverse Indigenous cultural and language

systems that continue to survive in villages throughout Alaska have a rich

cultural history that still governs much of everyday life in those communities. For

over six generations, however, Alaska Native people have been experiencing

recurring negative feedback in their relationships with the external systems

that have been brought to bear on them, the consequences of which have

been extensive marginalization of their knowledge systems and continuing

erosion of their cultural integrity. Though diminished and often

in the background, much of the Indigenous knowledge systems, ways of knowing

and world views remains intact and in practice, and there is a growing

appreciation of the contributions that Indigenous knowledge can make to

our contemporary understanding in areas such as medicine, resource management,

meteorology, biology, and in basic human endeavors, including educational

practices (James 2001).

In response

to these conditions, the following initiatives were developed and have

constituted the major thrusts of the AKRSI applied research and educational

restoration strategy:

Alaska Native

Knowledge Network

Indigenous

Science Knowledge Base

Multimedia

Cultural Atlas Development

Native Ways

of Knowing/Pedagogical Practices

Elders, Cultural

Camps and Traditional Values

Village Science

Applications, Camps and Fairs

Alaska Standards

for Culturally Responsive Schools

Native Educator

Associations

Over a period of

ten years, these initiatives have served to strengthen the quality of educational

experiences and have been shown to consistently improve the academic performance

of students in participating schools throughout Alaska (AKRSI Annual Report

2004). In the course of implementing the AKRSI initiatives, we have

come to recognize that there is much more to be gained from further mining

the fertile ground that exists within Indigenous knowledge systems, as

well as at the intersection of converging knowledge systems and world views. The

depth of knowledge derived from the long-term inhabitation of a particular

place that Indigenous people have accumulated over millennia provides a

rich storehouse upon which schools can draw to enrich the educational experiences

of all students. However, this requires more than simply substituting

one body of knowledge for another in a conventional subject-based curriculum—it

requires substantial rethinking of not only what is taught, but how it

is taught, when it is taught, where it is taught, and who does the teaching. With

these considerations in mind, we established the Alaska Native Knowledge

Network as a key component of the AKRSI effort, to serve as a framework

for documentation, analysis, dissemination and application of information

about Indigenous knowledge systems and their relevance in the contemporary

world.

Native Ways of Knowing and Traditional Values

Indigenous

peoples throughout the world have sustained their unique worldviews and

associated knowledge systems for millennia, even while undergoing major

social upheavals as a result of transformative forces beyond their control. Many

of the core values, beliefs, and practices associated with those worldviews

have survived and are beginning to be recognized as being just as valid

for today's generations as they were for generations past. The depth of

Indigenous knowledge rooted in the long inhabitation of a particular place

offers lessons that can benefit everyone, from educator to scientist, as

we search for a more satisfying and sustainable way to live on this planet

(Barnhardt and Kawagley 2005).

Actions

currently being taken by Indigenous people in communities throughout the

world clearly demonstrate that a significant "paradigm shift" is under

way in which Indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing are recognized as

constituting complex knowledge systems with an adaptive integrity of their

own (Barnhardt and Kawagley 2004). As this shift evolves, Indigenous people

are not the only beneficiaries—the issues are of equal significance

in non-Indigenous contexts. Many problems manifested within conditions

of marginalization have gravitated from the periphery to the center of

industrial societies, so that new (but old) insights emerging from Indigenous

societies are of equal benefit to the broader educational community.

Over many generations,

Indigenous people have constructed their own ways of looking at and relating

to the

world, the universe, and to each other (Barnhardt and Kawagley 1999; Eglash

2002). Their traditional education processes were carefully crafted

around observing natural processes, adapting modes of survival, obtaining

sustenance from the plant and animal world, and using natural materials

to make their tools and implements. All of this was made understandable

through demonstration and observation accompanied by thoughtful stories

in which the lessons were imbedded (Kawagley 1995; Cajete 2000). However,

Indigenous views of the world and approaches to education have been brought

into jeopardy with the spread of Western values, social structures and

institutionalized forms of cultural transmission.

Over the past ten years, Native Elders and educators

from every cultural region in Alaska have sought to reconnect with their

cultural traditions

through a variety of initiatives aimed at making explicit their expectations

for drawing upon their own ways in the up-bringing of their children and

grandchildren. For example, the following cultural values were drawn

from several lists of values adopted by Alaska Native Elders from each cultural

region in the state to serve as the core values

by which the community members, students and school staff are expected to

engage with one another and by which educational practices are to be implemented:

Respect for Elders

Respect for Nature

Respect for Others

Love for Children

Providing for Family

Knowledge of Language

Wisdom

Spirituality

Responsibility

Unity

Compassion

Love

Dignity

Honoring the Ancestors

Honesty

Humility

Humor

Sharing

Caring

Cooperation

Endurance

Hard Work

Self-Sufficiency

Peace

Such universal

values, once identified and adopted by Native communities, provide an invaluable

basis

on which to construct an educational system that is not only applicable

to Native students, but has relevance for all students. The metaphor

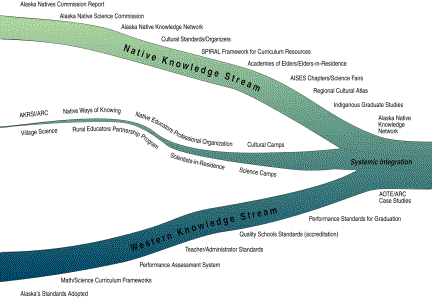

we've used to describe the processes we are engaged in with the Native

communities and schools is that of converging streams of knowledge, as

illustrated in the following diagram:

A variety of initiatives

have been implemented aimed at documenting the makeup of the Native knowledge

stream to make it more accessible to schools, along with parallel initiatives

aimed at loosening up the structure of the Western knowledge stream to

make room for the local contributions. In addition, initiatives such

as the Old Minto camp have illustrated how both knowledge streams can come

together in mutually productive ways. The goal of these efforts has

been to demonstrate the complementarity that can be achieved by understanding

the interaction of these knowledge systems in ways that increase both the

depth and breadth of learning opportunities for all students.

Recently, many

Indigenous as well as non-Indigenous people have begun to recognize the

limitations of

a mono-cultural, single-stream education system, and new approaches have

begun to emerge that are contributing to our understanding of the relationship

between Indigenous ways of knowing and those associated with Western society

and formal education. Our challenge now is to devise a system of

education for all people that respects the epistemological and pedagogical

foundations provided by both Indigenous and Western cultural traditions. While

the examples used here to illustrate that point will be drawn primarily

from the Alaska Native context, they are intended to be illustrative of

the issues that emerge in any context where efforts are underway to reconnect

education to a sense of place and its attendant cultural practices and

manifestations.

Alaska Native Knowledge Network:

Connecting Education to Place

As the AKRSI

effort began to accumulate a widening range of examples of the successful

merging

of Indigenous

and Western ways of making sense of the world, we sought to develop curricular

and pedagogical strategies that incorporated the experiential features

which served to bring the two systems of thought together. To share

the insights that were gained from this process and to promote the exchange

of materials and ideas among educators throughout Alaska and beyond, we

formed the Alaska Native Knowledge Network (ANKN), which consists of a

curriculum database, an extensive web site and listserv, and a publication

production and distribution facility. The following section will

illustrate some of the kinds of resources that have been developed through

the ANKN.

The primary vehicle

for promoting experiential, inquiry-based pedagogy has been the development

of curriculum

materials that guide teachers into the use of the local environment and

cultural resources as a foundation for all learning. A key incentive

for such practices has been the sponsorship of Alaska Native Science Camps

and Fairs in which students work with local Elders to identify topics of

local interest and develop projects illustrating the use of "science" in

everyday life in their community and environment. The science project

opportunities have been unlimited as Elders have shared their accumulated

knowledge derived from living on the land over many generations. For

example, the Minto Elders identified 72 uses of birch trees, many of which

provided intriguing opportunities for students to test the scientific principles

imbedded in the Elders knowledge (Why is bark for baskets harvested at

a certain time of the year?).

The projects prepared by the

students are judged by Elders as well as scientists, using two sets of

criteria to insure that the students have incorporated both culturally

accurate and scientifically valid principles and practices. This is a learning

process in which the teachers, Elders and students have all been eager

and willing participants, and we now have numerous examples of integrated

science/culture camps and fairs which clearly illustrate the ways in which

an extended period of experiential inquiry in a traditional camp environment

can serve as the stepping stone toward in-depth curriculum and instruction

back in the classroom (http://ankn.uaf.edu/anses/).

One of the major ANKN initiatives in the

area of curricula has been the creation of a clearinghouse and database

to identify, review and catalog appropriate national and Alaska-based curriculum

resources suitable for Indigenous settings, and make them available throughout

the state via the ANKN web site (http://www.ankn.uaf.edu). Access

to these resources has been expanded to include a CD-ROM collection of

the best materials in various thematic areas relevant to schools in Alaska. In

selecting culturally relevant materials for the database and CD-ROM collections,

we have sought to reach beyond the surface features of Indigenous cultural

practices and illustrate the potential for comparative study of deep knowledge

drawn from both the Native and Western streams. Examples of topical

areas for instruction in which opportunities for linking local knowledge

with the textbook curriculum are readily available are illustrated in the

lower portion of the following iceberg analogy:

The knowledge and skills derived from thousands

of years of careful observation, scrutiny and survival in a complex ecosystem

readily lends itself to the in-depth study of basic principles of biology,

chemistry, physics and mathematics, particularly as they relate to areas

such as botany, geology, hydrology, meteorology, astronomy, physiology,

anatomy, pharmacology, technology, engineering, ecology, topography, ornithology,

fisheries and other applied fields (cf. Carlson 2003; Denali Foundation

2004). Requests for the ANKN curricular materials listed in the ANKN

database has grown steadily, with over 800,000 "hits" from nearly 40,000

different individuals recorded on the web site each month. The CD-ROM

containing Village Science (http://ankn.uaf.edu/VS/index.html),

the Handbook for Culturally Responsive Science Curriculum (http://ankn.uaf.edu/handbook/),

and Alaska Science Camps, Fairs and Experiments (http://ankn.uaf.edu/Alaska_Science/)

has been an instant hit and is being used extensively in schools and professional

development programs throughout the state. It is the ready availability

of these resources that has given teachers the impetus to revamp their

curricula to integrate the place-based approach to education that has been

championed through the AKRSI.

The integration

of the curricular and pedagogical strategies outlined above into everyday

practice in schools

has been fostered in several ways. The first has been through the

promotion of Indigenous "organizers" as the basis for bringing all the

elements of the educational experience together in a framework that is

grounded in the cultural and physical environment in which the school is

situated. Guidelines and models to assist teachers and districts

in such development are now included in the Alaska curriculum frameworks

documents distributed by the Alaska Department of Education, as well as

through ANKN (cf. Scollon, 1988). A recent addition to the arsenal

of professional development activities that expose teachers to available

curriculum resources has been the regional implementation of cross-cultural

orientation programs for new teachers modeled on the Old Minto camp.

One of the vehicles

for bringing coherence to the ideas imbedded in the initiatives promoted

by the AKRSI

has been the development of a culturally-oriented curriculum framework

for purposes of organizing all the curricular and cultural resources that

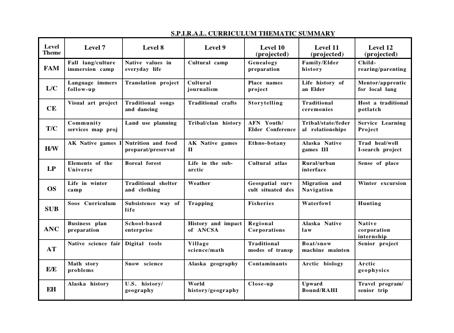

are emerging from the schools as a result of the various initiatives. The "Spiral

Pathway for Integrating Rural Alaska Learning" (SPIRAL), is structured

around 12 themes and grade levels, so that the compilation of curriculum

resources can be accessed by clicking on the appropriate theme and grade

level, which will then produce a codified list of available materials,

many of which can be down-loaded directly from the ANKN web site.

To take the place-based

curriculum structure imbedded in the SPIRAL thematic chart a step further,

a group

of Native educators from the Athabascan region of Interior Alaska have

developed a 7-12 Charter School (scheduled to open in the Fall of 2005),

in which the entire curriculum will be based on the SPIRAL framework and

will be implemented in a three-week modular format where students will

enroll in once course at a time and rotate through each of the 12 themes

on an annual year-round schedule. The specific components that will

make up the curriculum are summarized in the following chart, all of which

have been aligned with the State content standards.

Another

area in which the AKRSI is promoting initiatives impacting student/teacher,

school/curriculum interactions is in the use of technology to extend and

deepen learning opportunities for Native students. For those schools

that have full technology access, we have been providing training in implementing "cultural

atlases"—a CD-ROM/web site development project in which students

research any aspect of their culture/community/region and assemble the

information in a multimedia format through the use of technology. Cultural

atlases engage students in information gathering and compiling processes

that simultaneously enhance learning of subject matter, technology applications

and cultural knowledge, with the results often of direct interest and service

to their communities. Areas in which cultural atlases have been developed

by students in various schools around the state include life histories,

genealogies, place names, language documentation, uses of local flora and

fauna, subsistence practices, community histories, traditional arts and

crafts, mapping projects and weather knowledge. The AKRSI staff member

responsible for the cultural atlas initiative was invited to attend a UNESCO-sponsored

conference on "Multimedia and Invisible Culture," to illustrate

how technology can be used to help students connect and contribute to their

place (King

and Schiermann 2004).

Alaska Standards for Culturally Responsive Schools

One of the major constraints in achieving

long-term improvement of any kind in rural schools in Alaska is the persistent

high turnover rate among educational personnel (an average of one-third

annually in rural schools), coupled with a statewide Alaska Native teaching

staff of under five percent, when the Native student population constitutes

24% of the school enrollment. Therefore, the emphasis of the AKRSI

has been on implementing changes that can bring about a degree of stability

and continuity in the professional personnel in the schools, particularly

through the preparation of qualified Alaska Native teachers and administrators,

and engaging Elders and local experts in the educational process. This

has led to a focus on capacity building through the formation of

a series of regional Native educator associations to foster leadership

development on the part of those teachers for whom the community/region/state

is their home.

A turning point in the AKRSI efforts took place in 1998, when the Native

educators from each of the regional associations collectively produced and

adopted the Alaska Standards for Culturally Responsive Schools,

which have since been endorsed by the State Board of Education and are now

in use in schools throughout the state. The "Cultural Standards" embody

the cultural and educational restoration strategy of the AKRSI and have had

ripple effects throughout Alaska, in urban as well as rural schools. These standards have provided

guidelines against which schools and communities can examine the extent to

which they are attending to the educational and cultural well-being of their

students. They include standards in five areas: for students, educators,

curriculum, schools and communities. The emphasis is on fostering a strong

connection between what students experience in school and their lives out

of school by promoting opportunities for students to engage in in-depth experiential

learning in real world contexts.

Culturally responsive education is directed

toward culturally-knowledgeable students who are well grounded in the cultural

heritage and traditions of their community and are able to understand and

demonstrate how their local situation and knowledge relates to other knowledge

systems and cultural beliefs. This includes:

In this respect, the incorporation of the Alaska Standards for Culturally-Responsive

Schools in all aspects of the school curriculum

and the demonstration of their applicability in providing multiple alternative

avenues to meet the State content standards is central. As indicated

in the cultural standards, culturally responsive curricula:

- reinforce the integrity

of the cultural knowledge that students bring with them;

- recognize cultural knowledge

as part of a living and constantly adapting system that is grounded in

the past, but continues to grow through the present and into the future;

- use the local language

and cultural knowledge as a foundation for the rest of the curriculum

and provide opportunities for students to study all subjects starting

from a base in the local knowledge systems;

- foster a complementary

relationship across knowledge derived from diverse knowledge systems;

- situate local knowledge

and actions in a global context: Ąthink globally, act locally';

- unfold in a physical environment

that is inviting and readily accessible for local people to enter and

utilize. (ANKN, 1998, p. 13-19)

Summary

The primary thrust of the Alaska Native Knowledge Network in its effort to

create a place for Indigenous knowledge in education can best be summarized

by the following statement taken from the introduction to the Alaska

Standards for Culturally Responsive Schools:

By shifting the

focus in the curriculum from teaching/learning about cultural heritage as another

subject to teaching/learning through the local culture as a

foundation for all education, it is intended that all forms of knowledge,

ways of

knowing and world views be recognized as equally valid, adaptable and

complementary to one another in mutually beneficial ways. (ANKN,

1998, p. 3)

While much remains

yet to be done to fully achieve the intent of Alaska Native people in seeking

a place for their knowledge and ways in the education of their children,

they have

succeeded in demonstrating the efficacy of an educational system that

is grounded in the deep knowledge associated with a particular place, upon

which a broader knowledge of the rest of the world can be built. This

is a lesson from which we can all learn.

REFERENCES

[Most of the references cited

in this article can be found on the Alaska Native Knowledge Network web

site at http://www.ankn.uaf.edu]

Alaska Rural Systemic

Initiative

2004

Annual Report. Fairbanks: Alaska Native Knowledge Network

(http://ankn.uaf.edu/old/AKRSI_2004_Final_Report.doc), University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Alaska Native

Knowledge Network

1998 Alaska

Standards for Culturally Responsive Schools.

Fairbanks: Alaska Native Knowledge Network (http://ankn.uaf.edu/standards/), University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Barnhardt, Ray

and A. Oscar Kawagley

2005

Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Alaska Native Ways of Knowing. Anthropology

and Education Quarterly 36(1): 8-23.

Barnhardt, Ray

and A. Oscar Kawagley

2004

Culture, Chaos and Complexity: Catalysts for Change in Indigenous

Education. Cultural

Survival Quarterly 27(4): 59-64.

Barnhardt, Ray

and A. Oscar Kawagley

1999

Education Indigenous to Place: Western Science Meets Indigenous

Reality. In Ecological Education in Action.

Gregory Smith and Dilafruz Williams, eds. Pp. 117-140. New York:

State University of New York Press.

Boyer, Paul

2005

Alaska: Rebuilding Native Knowledge. In Building Community:

Reforming Math and Science Education in Rural Schools.

Paul Boyer. Washington, D.C.: National Science Foundation.

Cajete, Gregory

2000 Native

Science: Natural Laws of Interdependence.

Sante Fe, NM: Clear Light Publishers.

Carlson, Barbara

S.

2003 Unangam Hitnisangin/Unangam

Hitnisangis: Aleut Plants.

Fairbanks: Alaska Native Knowledge Network (http://ankn.uaf.edu/Unangam/),

University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Denali Foundation

2004 Observing Snow. Fairbanks: Alaska Native Knowledge Network

(http://ankn.uaf.edu/ObservingSnow/),

University of Alaska Fairbanks,

Eglash, Ron

2002

Computation, Complexity and Coding in Native American Knowledge Systems.

In Changing the Faces of Mathematics: Perspectives on Indigenous People

of North America.

Judith E. Hankes

and Gerald R. Fast, eds. Pp. 251-262. Reston,

VA: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

James, Keith,

ed.

2001 Science

and Native American Communities.

Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Kawagley, A.

Oscar

1995 A

Yupiaq World View: A Pathway to Ecology and Spirit.

Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press.

King, Linda and Sabine Schiermann

2004 The Challenges of Indigenous Education:

Practice and Perspectives. Paris: UNESCO

Scollon, Ron

1988 The Axe Handle Academy: A Proposal for

a Bioregional, Thematic Humanities Curriculum. In R. Barnhardt & K.

Tonsmeire (Eds.), Lessons Taught, Lessons Learned. Fairbanks, AK: Center for Cross-Cultural Studies

(http://ankn.uaf.edu/axehandle/index.html),

University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Stephens, Sidney

2000 Handbook

for Culturally Responsive Science Curriculum.

Fairbanks: Alaska Native Knowledge Network(http://ankn.uaf.edu/handbook/),

University of Alaska Fairbanks.