The

Educational Achievement of Indian Children

CHAPTER I

Introduction

PREVIOUS STUDIES

The years 1944, 1945, and 1946 marked an unusual

departure in Indian education, for it was during these years that

a service-wide evaluation

of Indian education was conducted for the Bureau of Indian Affairs

by the Department of Education of the University of Chicago. This

service-wide evaluation was presented in a monograph entitled How

Well Are Indian Children Educated? The monograph was a summary

of the results of a three-year program testing the achievement

of Indian children in federal, public, and mission schools. This

excellent contribution to Indian education was authored by Dr.

Shailer Peterson, then of the University of Chicago. The monograph

also included chapters by Dr. Ralph Tyler of the University of

Chicago, and Dr. Willard Beatty, Chief, Branch of Education of

the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The volume was printed at the Haskell

Institute Print Shop, Lawrence, Kansas, in September of 1948.

PROBLEMS OF INDIAN EDUCATION

In order to orient the reader to Indian education and its problems,

we quote: 1

The Indian Bureau-wide Testing Project, reported in this monograph,

had two main purposes: (1) to examine the progress and achievement

that the Indian students had made in various types of educational

situations; (2) to examine those factors which were thought to

be related to the student's educational development and to uncover

any other factors which might prove to be related.

This first chapter becomes, in a sense, a summary of the monograph,

for it answers with information gathered from this study many of

the questions commonly raised by those interested in Indian education.

Moreover, this chapter provides some of the background essential

to an understanding of the study and the information that it has

revealed.

The following chapters describe in detail the methods by which

the test battery was developed, administered and interpreted.

For approximately twelve years, there has been a definite and expressed

philosophy directing the program of education in the schools of

the United States Indian Service. This is summarized in the introductory

statement of the Civil Service examination prepared for the Indian

Service teachers. It reads as follows:

The primary objectives of Indian schools are: To give students

an understanding and appreciation of their own tribal lore, art,

music, and community organization; to teach students through their

own participation in school and community government to become

constructive citizens of their communities; to aid students in

analyzing the economic resources of their reservation and in planning

more effective ways of utilizing these resources for the improvement

of standards of living; to teach, through actual demonstration,

intelligent conservation of natural resources; to give students

firsthand experience in housing anal clothing, in subsistence gardening,

cooperative marketing, farm mechanics, and whatever other vocational

skills are needed to earn a livelihood in the region; to develop

better health habits, improve sanitation, and achieve higher standards

of diet with a view to prevention of trachoma, tuberculosis, and

infant diseases; to give students an understanding of the social

and economic world immediately about them and to aid them in achieving

some mastery over their environment; and to serve as a community

center in meeting the social and economic needs of the community.

Obviously this philosophy has required attention to training Indian

children so that they may be able to make a living from the natural

resources of their home environment, as well as to make a living

away from their reservation. This educational program has not resulted

in neglecting the usual type of academic instruction which includes

reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, history, and science.

Instead, to these academic subjects has been added emphasis on

those skills needed to make the best use of the resources of the

environment. These extra skills have included an understanding

of desirable health practices, domestic living, and practical training

in one or more of a variety of vocational fields, each of which

is important not only on the reservation but away from the reservation

in both rural and urban localities.

It is evident that education is as important in the life of an

Indian as it is in the life of a non-Indian. Many Indian children

do not come to school the first day possessing a familiarity with

the English language or with much of the background experience

which is common to the lives and environment of most white children.

Experiences and skills that are taken for granted by the teachers

of white children in the kindergarten or first grade cannot be

taken for granted by the teachers of Indian children.

One out of every three children from the hills of eastern Oklahoma

or from the Dakota Sioux reservations comes with an extremely limited

English vocabulary, being accustomed to doing most of his speaking

and thinking in his native Indian language. In the Papago country

of southern Arizona and throughout the Navaho reservation, the

great majority of children who enroll in the federal schools are

unable to understand English at all when they enter school. The

teachers of such children are therefore confronted with students

who have been speaking and thinking in only their native tongue.

Among the Pueblos, still another problem presents itself, for here

many of the children are trilingual, speaking a little Spanish

and a little English mixed with a large proportion of Indian dialect.

The problem of having to teach the student English before he can

be taught reading, writing, arithmetic, and geography is peculiar

to the Indian Service. Few public schools, other than those located

on the Mexican border, have a similar problem. In most public schools,

it is the exception if teachers are confronted with a non-English-speaking

child. In the Indian Service, some schools rarely have beginning

students who know English, and in almost all schools the language

problem is ever present.

In federal schools the curricula and teaching methods are necessarily

different from those employed in most public schools because of

the differences which exist between beginning Indian children and

white children. Teachers who have had their training and practice

teaching in the environment of the average public school find the

problems of the Indian school to be quite different. In-service

training programs have been necessary to prepare the new teachers

for this new kind of experience. Special summer school training

and specially prepared materials have been used to acquaint new

teachers with the problems which are not a part of most methodology

textbooks.

Those who are uninformed or misinformed about the problems

of Indian education are often critical when they learn that

Navaho youngsters

are a year or two behind the grade level expected of white children

of the same age. Those who find Indian Bureau schools devoting

a large part of the first year to the acquisition of a useful

and functional English vocabulary, consider it strange that

the teaching

of reading is usually delayed to the second year. Similarly,

new Indian Service teachers coming from the public schools

at first

wonder why it is that the Bureau of Indian Affairs does not advocate

close adherence to those courses of study commonly accepted and

advocated for the public schools of the states in which the Bureau

of Indian Affairs operates. These new teachers first fear that

without these "accepted" courses of study, their students

cannot possibly make satisfactory progress.

Those who have directed the Indian schools have watched the results

of their specially adopted program of teaching, and have made changes

and modifications as they seemed desirable. In the past, however,

there has not been a planned evaluation program for obtaining an

over-all picture of Indian education through the years. The absence

of such information is particularly notable now that data are being

gathered about the present status of the educational program. A

point of reference for comparison purposes would now be very useful.

In 1944, the Chief, Branch of Education, Bureau of Indian Affairs,

and his associates requested the cooperation of the Department

of Education of the University of Chicago, in planning and administering

a service-wide evaluation in an endeavor to answer numerous questions

which have arisen over the years. The details of this cooperative

effort will be described in the following chapters of this monograph.

The remainder of this chapter will be .devoted to reporting the

results of three years of a carefully conducted evaluation program

by listing the questions that have been asked and giving the answers

that have so far been obtained.

THE PREVIOUS TESTING PROGRAM

The scope and comprehensiveness of the testing programs conducted

in 1944, 1945, and 1946, is best shown by quoting from Peterson's

monograph:2

Indian groups throughout the country differ greatly in their cultural

background. Some Indian school children belong to tribes to whom

educational opportunities have been available for as long as 150

years, whereas others belong to tribes in which these children

are the first generation to whom educational opportunities have

been available. Differences also exist as a result of contrasting

environments. Many Indian children are bilingual and most of them

have rural backgrounds. Since most standardized tests depend upon

language-the language of urban life-such tests have limitations.

An evaluation of the achievement of Indian children by merely comparing

their scores on verbal tests with the scores of white children

from urban communities would tell little or nothing concerning

the attainment of the Indian children. It had been suggested that

one might find relatively little difference between the achievement

of Indian children who attend public schools and white children

from rural environments, since those who attend public schools

come from less isolated environments than do the majority of the

Indian children in federal schools. Another factor indicated for

study was the difference in environment offered to pupils by different

kinds of Indian schools.

Most day school students have no contact with English except during

the few hours when they are in school, whereas the students in

boarding schools are exposed to English during the entire twenty-four

hours of the day. Probably the most important difference in school

environment is that which relates to the special curricula provided

students in Indian schools. The home environment of most Indian

students does not provide them with certain types of training in

health practices, rural practices and home economics, which most

rural white children receive at home. Because of this, the Indian

schools attempt to provide those things which are not always included

in the public school curriculum. Moreover the vocational objectives

of many of the Indian groups differ from the objectives of other

Indian groups or white students to the extent that the curriculum

in each school must be adapted to the special needs of its students.

It was decided that certain measuring instruments should be tried

experimentally during 1944, the first year of the study. Staff

members from the Branch of Education, Bureau of Indian Affairs,

with the assistance of staff members of the department of Education

of the University of Chicago, analyzed existing tests. Where suitable

tests were not available, they constructed tests in those fields

of rural life education to which Indian schools devote considerable

attention. The selection and preparation of the measuring instruments

finally employed, resulted from a consideration of the following:

(1) the immediate and far-reaching purposes of the testing program,

(2) the educational program suited to the needs of students now

enrolled in Indian schools,

(3) the level of Indian pupil achievement in tool subjects such

as reading, English, arithmetic and penmanship,

(4) the effect that certain differences in educational and home

environments (e. g. school attended, language of the parents, etc.)

may have had upon the Indian student's achievement,

(5) the available measuring instruments with particular reference

to:

(a) their wide age or educational range, thereby making the test

suitable for students with widely differing abilities,

(b) reliability or dependability of the measure,

(c) validity for purposes intended,

(d) simplicity of directions,

(e) ease of indicating answers or choices,

(f) simplicity of scoring,

(g) availability of useful norms,

(h) strange or unusual vocabulary,

(6) the assembly of information that will provide a better understanding

of Indian students and their families,

(7) the assembly of information which lends itself to a useful,

long-range program.

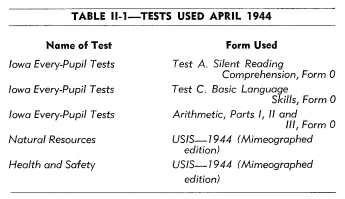

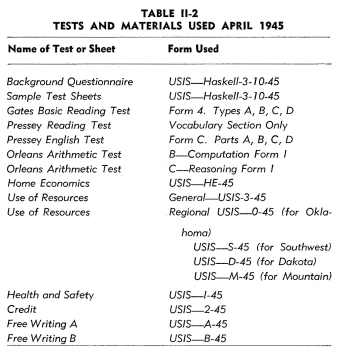

Table II-1 lists the evaluation instruments that were selected

or prepared for use in the trial program in 1944. The standardized

tests included were selected because it was believed they would

meet many of the requirements of the program.

The Iowa Every-Pupil Tests, used in the trial battery of tests,

employ a rather complicated system of answering items in order

to facilitate mechanical scoring. Such a scheme presented an additional

and unnecessary hurdle to Indian children, unfamiliar with this

method of response. A review of the difficulties encountered by

the students on items in the reading and arithmetic tests in the

Iowa battery also revealed that the types of errors seemed to be

caused by the fact that the content material was foreign to rural

experience, thereby defeating the purposes of the tests. For those

two reasons, the Iowa battery was replaced in 1945 by other tests

as indicated in Table II-2.

The Indian Bureau tests in Natural Resources and Health and Safety

(the Rural Practices Tests) administered experimentally in 1944

proved to contain certain language hurdles. Consequently, these

tests were revised in the light of these findings and other tests

were prepared for inclusion in the 1945 program. In all of these,

there was an effort to minimize the reading skill required for

understanding anal responding to each content item.

The pilot study of 1944 was exceedingly helpful in revealing many

additional factors which required consideration in this program.

The results were based on samples too small to warrant any conclusions

concerning the achievement of Indian students.

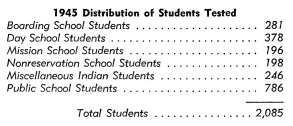

As indicated in Chapter 1, it was decided that the 1945 program

should include all of the eighth grade students in Indian schools,

as well as students in a selected group of public and mission schools.

The total number of students tested in each type of school was

as follows:

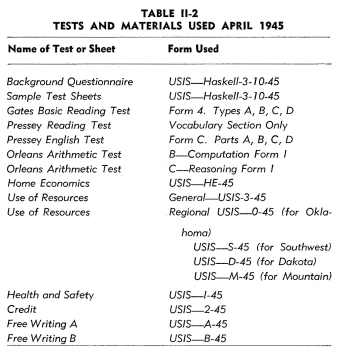

The test battery was administered in each of the schools by personnel

selected by the area superintendent of education. Only persons

who had previously had test experience were used in the administration

and in 1945 the tests were administered by persons not connected

with the schools in which they were given. Table II-2 lists the

test battery given to all eighth grade students in the spring of

1945.

All of the papers from this program were scored in the Chicago

Office by a group of well-qualified teachers. Reports on the performance

of each individual student within a school, together with graphic

norm sheets showing the distribution of scores in each type of

school and in each region included, were then distributed to the

administrators of the schools that participated.

A good many tentative conclusions, discussed in detail in the following

chapters, resulted from the data collected and assembled in 1945.

In addition, the need for other, specific data became apparent.

It was recognized that many questions can be answered only by following

the progress of the same students during a period of several years.

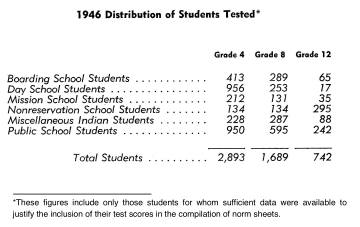

However, it was decided to extend the student sample to include

students in grades four and twelve the following year, in order

that differences in relation to grade level could be observed.

In 1946, the tests were administered again to students in selected

public and mission schools in order that comparative data for rural

white children, and for Indian children in public and

mission schools might be available. The total number of students

tested in each grade and in each type

of school was as follows:

The standardized tests used in the 1945 program proved sufficiently

satisfactory so that all of them were included in the 1946 battery

for twelfth grade students. Several of the same tests were administered

to fourth graders in 1946. Use of identical test instruments

both years made it possible to compare the new data with that

collected from the eighth grade students the previous year. This

eliminated the necessity of repeating all of the tests at the

eighth grade level in 1946. Many of the schools were supplied

with all tests for the eighth grade students at their own request,

in order that they might collect additional information on the

students in their own schools. The 1945 Credit Test was omitted

because the number of items in the test was so small that it

was decided to include them at a later date as a part of another

test. The use of regional tests in resources presented a number

of problems which made it seem advisable to incorporate those

items which tended to be somewhat general in nature, into the

General Resources Test. In this test all items clearly having

only regional significance were omitted. The Rural Practices

Vocabulary Test was constructed and administered to students

in grades eight and twelve. The Gates Advanced Primary Reading

Tests were selected for testing the reading achievement of the

fourth grade students. The Background Questionnaire was revised

to include additional data for study. Table 11-3 lists the tests

included in the 1946 battery.

**These principals who wished to do so were permitted to administer

these tests to eighth grade students in their own schools.

It was decided that the problems of test administration and scoring

would be considerably lessened by the use of a larger number of

administrators, and by having the multiple response type test scored

in the field. Through the cooperation of area superintendents of

Indian education, persons who were well qualified to follow the

detailed instructions furnished to them were selected to administer

the tests in 1946. In some instances it was recommended that the

tests be administered by the classroom teacher. The manual of instructions

was prepared in sufficient detail to make the test administration

relatively uniform. Area superintendents also arranged for the

scoring of all except the Free Writing test. Rechecking indicated

that a high degree of grading accuracy was maintained in the field

scoring. All of the Free Writing Tests were scored by a small group

of teachers who worked under the supervision of one of the staff

members from the Chicago Office.

To facilitate a more comprehensive analysis of background data

and test results, all of the data collected were coded and entered

on punch cards so that machine computations would be possible.

Provision has been made to add data to these punch cards from time

to time to facilitate growth studies and for making other comparisons.

THE 1950 TESTING PROGRAM

Having provided the reader with some background information regarding

Indian education and its problems as well as the nature of the

1944-45-46 testing programs, we turn our attention now to the purpose

of the present report.

The present monograph is concerned with the results of the 1950

Service-Wide Testing Program planned and supervised by L. Madison

Coombs, Education Specialist, Bureau of Indian Affairs.

The purpose of the 1950 Service-Wide Testing Program was given

in the Manual of Instructions for Test Administration and reads

as follows:

As in former years one of the major purposes of the administration

of tests to Indian students in the 1950 program is to provide schools

with additional information about students that may be useful in

the guidance of these students. In keeping with this purpose, tests

have been selected, adapted, and constructed with these students

in mind. These tests are designed to provide measures of a number

of important abilities or aptitudes, special achievements, and

interests.

The testing done this spring will, in a sense, complete

the cycle begun by the 1946 testing, results of which were

published by Dr.

Shailer Peterson in the monograph, "How Well Are Indian Children

Educated?" Pupils at the fourth and eighth grade levels in

1946 are now, assuming normal progress, at the eighth and twelfth

grade levels, respectively, in 1950. A re-testing at these last

named grade levels this spring should provide much illuminating

data.

As explained on the page titled, "Test Schedule," not

all of the tests given to the twelfth grade will be administered

to eighth grade students.

This is not an annual all-pupil testing program

such as some state departments and school systems have inaugurated.

Instead it is

an attempt to provide additional information to the schools so

that school personnel may have a better basis on which to guide

students and to initiate curriculum studies. It is also important

that all school personnel understand that the items included in

the various tests do not constitute a list of facts or

skills that should be mastered by all students in the Indian Schools.

These

do not, in any sense, constitute an approved course of study. The

range of the tests included is wide in order that they may be used

at various grade levels and in different types of schools. Criticisms

of any of the items in any of the tests will be welcome, for they

will be valuable in future revisions of the tests. Neither the

quality of instruction in any school nor the efficiency of any

teacher will be judged by the results of these tests.

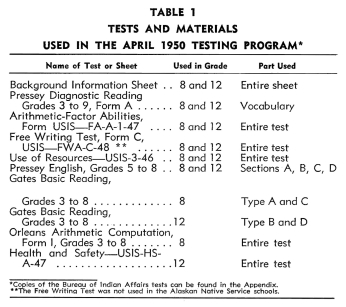

The tests and materials administered in the 1950 testing program

and used in this study are shown in Table 1.

THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS

The 1950 testing program was outlined and administered prior to

the completion of a contract between the Bureau of Indian Affairs

and the University of Kansas. Therefore, consultants from the

School of Education at the University of Kansas began advisement

at the point of punching and sorting of the information gathered

in the 1950 testing program by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

The results of this monograph are in a sense, therefore, a post-mortem

on the information gathered. This in no way is meant to imply

that the testing program was not wisely planned and administered.

It is simply to point out the time that the consultants of the

University of Kansas entered into the study. The late entry of

the University of Kansas consultants made their task somewhat

more difficult than it would have been if they had participated

in the study from the beginning. In addition, some of the data

obtained by administering some of the tests listed in Table 1

were not used in this study. The chief reason for only partial

utilization of the data was that some of the tests were measuring

abilities that had not been definitely established and explored.

In other words, the consultants were not sure just what abilities

some of the tests were measuring and whether the tests were doing

a good job of measuring the stated abilities.

SUMMARY

It was the purpose of this chapter to present a review of the events

leading up to the 1950 testing program. The brief discussion of

Indian education and the previous evaluations of Indian education

should prove of value to the reader in the forthcoming pages. The

present study does not depart markedly from the previous studies

of Indian education but is rather a continuation and extension

of those studies. The entrance of new evaluators to the scene must

of necessity change the points of emphasis here and there. Departures

from the previous studies were introduced whenever they clarified

the issues involved.

1 Shailer Peterson. How Well Are

Indian Children Educated? Lawrence, Kansas, Haskell Institute Print Shop, 1948. pp. 9-12.

2 ibid. pp. 20-26.

|