The

Educational Achievement of Indian Children

CHAPTER II

Differences In Student

Backgrounds

INTRODUCTION

Since the present study was designed to complete the

cycle begun by the 1946 testing, the information gathered by means

of the Background

Questionnaire in the 1950 study was essentially the same as in

1946. Peterson3 had this to say regarding this phase of the investigation:

A great many statements have been made and articles written describing

the Indian student, often drawing comparisons between him and white

pupils. Good or poor achievement has frequently been explained

on the basis of racial or cultural differences between the two

groups. Up to the time of this study, no service-wide survey has

collected the data needed to draw valid conclusions in regard to:

(1) the actual difference between the achievement of Indian students

and white children from rural areas,

(2) cultural differences between the two groups, or

(3) the relation between achievement and cultural differences.

It may be said therefore that the objective of this survey is three-fold:

(1) to measure the educational achievement of students in Indian

schools,

(2) to gather data relative to the cultural backgrounds of the

Indian and non-urban white students in Indian, public and mission

schools, and

(3) to determine the relationships, if any, which exist between

these measures of cultural background and school achievement.

Practical limitations made it necessary to collect cultural data

on a relatively small number of topics, but those which were selected

for study were those which seemed likely to be most important as

an aid to interpreting the test data and also as indication of

the other information which should ultimately be collected during

the following years of the study.

However, the present study was concerned chiefly with finding an

answer to the question: How well are Indian children educated?

This basic question was broken down into several specific questions

as follows:

1. Is the educational achievement of Indian children in some geographic

areas greater than in others?

2. Is the educational achievement of Indian children in some types

of schools greater than in others?

3. Is the educational achievement of Indian children in the various

types of schools they attend, as great as that of non-Indian children

in rural public schools?

4. What factors are in operation to produce differences in achievement

of Indian children in the different areas, in different types of

schools, and in contrast to non-Indian children in public schools?

5. The superior performance of fourth grade Indian children on

the 1946 tests, led to the tentative conclusion that the more systematically

organized program of instruction keyed to Indian needs, accounted

in large part for this clear-cut superiority, and raised the question

as to whether these same pupils at the eighth grade level would

also show an achievement superior to that of previous eighth graders

who had not had the benefit of basic instruction under the new

Indian school educational program. Therefore, the following question:

On tests common to both the eighth and twelfth grades, what is

the percentage of overlap or what percentage of the students in

the eighth grade exceeded the mean of the twelfth grade?

COMPOSITION OF TYPES OF SCHOOLS BY AREAS

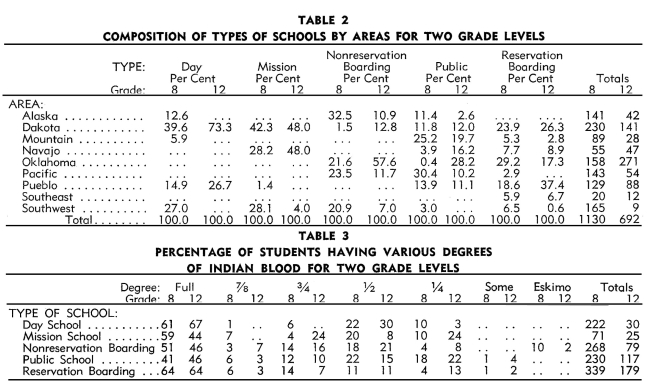

Many of the comparisons that follow later in Chapter 3 will be

more meaningful if one knows the areas represented in the 1950

testing program. Table 2 shows the composition of the types of

schools by areas for the students in grades eight and twelve in

this study. For example, a large proportion of the students in

the eighth and twelfth grades who attended Government reservation

boarding schools lived in the Dakota, Pueblo, and Oklahoma areas.

A majority of the Indian children in the eighth grade in this study

who attended public schools lived in the Mountain and Pacific areas.

CULTURAL BACKGROUNDS OF THE STUDENTS

Degree of Indian Blood Degree of Indian Blood

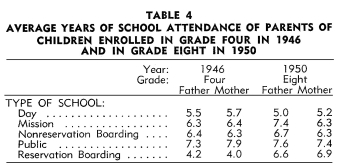

Table 3 describes the degree of Indian blood of the students in

the two grade levels in the different types of schools. The Peterson

report also listed the degree of Indian blood according to the

different

geographic areas. This information was also obtained for this report

but since the data were essentially the same as in the 1946 study,

they were not recorded here. The same was true of the information

gathered on other factors considered in this chapter and therefore

it has not been included in this report.

Essentially the some generalizations were obtained with regard

to the degree of Indian blood as in the 1946 report,4 namely:

(1) Nearly all of the students in the Navajo, Pueblo and other

Southwest schools are full blood Indians.

(2) There is a larger percentage of mixed blood students in the

non-reservation schools than in any of the other types of Federal

Indian schools.

(3) The public schools and mission schools selected for comparison

have a fairly wide range of students, extending from the full blood

Indians to all-white students.

Since this report is concerned essentially with comparisons of

achievement of Indian children in the various types of schools

they attended, the third generalization listed above is important.

If the public schools and the mission schools selected had contained

only full blood Indians, it would have been difficult to compare

the achievement of the Indian children in these schools with the

Indian children in government schools where the degree of Indian

blood ranged from full blood to some Indian blood. This is assuming

that the degree of Indian blood is a factor in school achievement.

The evidence presented in the 1946 study with regard to this question

was inconclusive.

Education of Parents Education of Parents

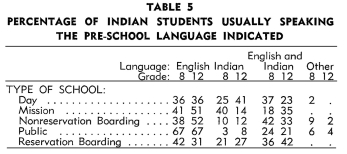

Table 4 indicates the average years of school attendance of parents

of children enrolled in the fourth grade in the 1946 report and

the eighth grade in this report. The educational attendance of

the parents of the students in the twelfth grade in 1950 was not

available. Peterson concluded that the “students coming from

homes in which parents have had the advantage of considerable education,

tend to remain in school longer than those coming from homes where

the parents have had little or no schooling.”5 Table 4 neither

confirms nor denies Peterson's conclusion. However, the parents

of Indian children enrolled in the public schools had the highest

average years of school attendance when compared with parents of

Indian children enrolled in the other four types of schools.

A study of drop-outs in the Lawrence Junior High School, Lawrence,

Kansas,6 revealed that the average school grade reached by the

mothers was 8.1 and that reached by the fathers was 7.7. Both of

these values are higher than those listed for the Indian children

in grade eight in Table 4. The average school grade reached by

the parents of all junior high school students in the Lawrence

school would be much higher.

In a study of a representative group of North Central High Schools

in Kansas, about eighty-eight per cent of the adults, in the communities

in which these schools were located, had completed the elementary

school or higher.7

Any conclusions, therefore, regarding the achievement of Indian

students in the various schools and white students in public schools

should be tempered by the fact that the educational level reached

by the parents of Indian children is probably considerably less

than that reached by the parents of white children in public schools.

Language Spoken in the Home Language Spoken in the Home

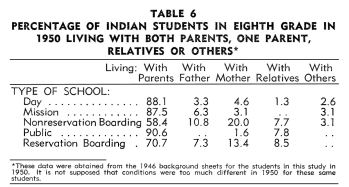

Table 5 describes the pre-school language usually spoken by the

eighth and twelfth grade Indian students in the 1950 study. Peterson

had this to say about the language spoken in the homes of Indian

children in the 1946 study:"8

It should be noted that this represents the language which the

student reported as that which is actually spoken in the home?not

the homes in which one or both parents can talk and understand

enough English to converse in that language if necessary. There

is evidence that many students who, because they speak English

habitually around school and are thought of as English-speaking,

actually speak only Indian when they are at home. It is also apparent

that many adult Indians who speak perfectly good English when necessary,

elect to converse in their Indian language at home. It will be

noted that the students in day schools come from homes in which

less English is spoken than do the students in any of the other

types of Indian schools. As would be expected, the public school

children have by far the greatest amount of English spoken in their

homes. This is true for Indian students in public schools, as well

as for whites in public schools. A much greater proportion of English

is spoken in the homes of the twelfth grade students in Indian

schools, and the proportion for the eighth grade is greater than

that for the fourth grade. The language spoken in the home appears

to be correlated with school achievement and also with the number

of years the student remains in school.

Although the information was not available, observations have indicated

that English was the predominant language spoken in the homes of

white children in the public schools in this study. Therefore,

any conclusions regarding the achievement of Indian students in

the various schools and white students in public schools should

be tempered by this fact.

Home Stability Home Stability

Table 6 describes the home stability of the students in the eighth

grade by indicating the percentage living with their parents, with

only their father, with only their mother, with relatives, or with

others. Data for the twelfth grade were not available. The following

statement appeared in the 1946 study:9

These data do not appear to have a direct or easily interpretable

relationship with any of the achievement scores, or with home factors

studied, but they will probably prove of value and interest in

personnel and adjustment studies. For example, the percentage of

students living with both parents is much smaller among students

in non-reservation boarding schools than in any other type of school.

* The data do not indicate, of course, that the broken home is

never a factor in the poor achievement of an individual student,

but they do indicate that, whatever the adverse effects of a broken

home may have been among these students, they are concealed by

other factors more directly affecting achievement.

*Dependency because of a broken home is one criterion for admission

to a non-reservation boarding school.

The important thing to note in Table 6 is that the percentage of

students falling into the various categories did not differ too

widely in the various types of school which these Indian children

attended. If home stability is a factor in school achievement,

the students who attended the non-reservation schools should not

have achieved as much as students who attended the other types

of schools. Although the data were not available, observations

indicate that a greater percentage of the white children in the

public schools in this study lived with their parents than was

true of the Indian children in the various schools. This factor

must be considered when comparing the achievement of Indian children

in the various schools and white children in the public schools.

Permanent Residence Permanent Residence

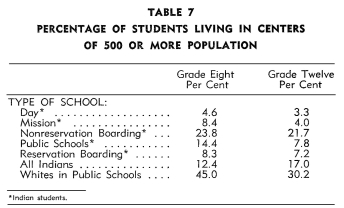

Table 7 indicates the percentage of students in the various types

of schools living in urban centers of 500 or more population. The

Indian children enrolled in the non-reservation boarding schools

and in the public schools lived in population centers more urban

than the Indian children who attended the other types of schools.

A much greater percentage of the white children in public schools

in this study lived in urban centers than was true of Indian children

in any of the types of schools they attended. Certain cultural

advantages are open to youngsters living in urban centers that

are not available to those living in rural areas. It would be expected

that Indian children living in urban centers might assimilate the

white man's culture more rapidly than Indian children living in

rural areas. Any conclusions, therefore, regarding the achievement

of Indian children and white children in public schools should

take the facts revealed in Table 7 into consideration.

Kinds of Friends Kinds of Friends

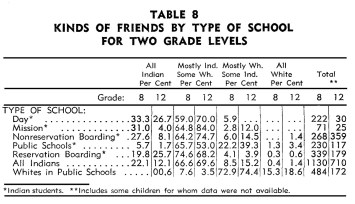

Table 8 reveals percentages of the kinds of friends of Indian children

who attend the various schools for Indians and the kinds of friends

of white children who attend the public schools included in this

study. If contact with white children is a factor in school achievement,

then the Indian children attending the public schools should achieve

more than the Indian children attending the other types of schools

for Indian children. The Indian children in the twelfth grade in

this study apparently have more contact with white children. Therefore,

if contact with white children is a factor in school achievement,

then the Indian students in the upper grades should compare more

favorably with white children in school achievement than the Indian

children in the lower grades.

EDUCATIONAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE STUDENTS

Grade Placement and School Attendance Grade Placement and School Attendance

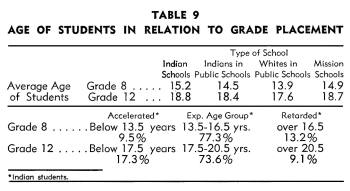

Table 9 shows the average age of the students in grades eight and

twelve in the 1950 study. These values are almost identical with

those given in the 1946 study. However, the percentages of students

accelerated in the eighth and twelfth grades in 1946 were 4.5 per

cent and 15.9 per cent respectively,10 as contrasted to 9.5

per cent and 17.3 percent respectively in the 1950 study. However,

the gain in acceleration in the eighth grade was offset by an increase

in retardation, the percentage of retardation being 6.8 per cent

in 1946 as contrasted to 13.2 per cent in 1950. In the twelfth

grade in 1950, there was an increase in the percentage of students

accelerated and in the expected age group and a decrease in the

percentage of students retarded when compared with the values given

in the 1946 study. Whether or not this trend represents a change

in promotional policy or a dropping out of less capable students

was not revealed by the information gathered.

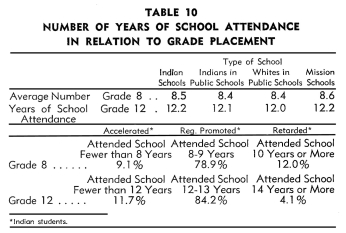

Table 10 indicates the number of years of school attendance in

relation to grade placement. The average number of years of school

attendance was almost identical with that reported in the 1946

study.11

Here again the comparison with regard to accelerated, regularly

promoted, and retarded students is almost the same as mentioned

previously with regard to Table 9.

In a study of a group of Kansas North Central high schools,12 the

percentage of over-ageness decreased from grades nine to twelve,

while the percentage of youngness increased. This trend noted in

Tables 9 and 10 for Indian children is typical of white children

in the public schools. The decrease in the percentage of retarded

students in the upper grades may be partially explained by acceleration

during the interval or because more of the students now entering

have difficulties that result in early retardation.

The percentage of students in the twelfth grade in the Kansas North

Central high schools who were older than 17.5 years, was 17.6 per

cent. The percentage of students in the twelfth grade in the Indian

schools in this study who were over 17.5 years was 82.8 per cent.

Thus, it is apparent that the Indian students in the twelfth grade

in this study were considerably retarded when compared with white

students in typical public high schools. There are many reasons

for this retardation, the chief one probably being the late entrance

of many Indian students in school. Thus, any conclusions regarding

the achievement of Indian students in the various schools with

white children in public schools must be tempered by differences

in the ages of students in relation to their grade placement.

Size of School Attended Size of School Attended

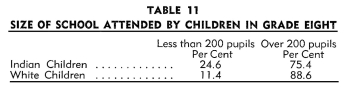

Table 11 presents some information regarding size of school attended

by Indian children, and white children in public schools. The number

of cases for grade twelve for white children in public schools

was far too few to make a comparison. Two studies13, 14 have shown

the size of the school to be a factor in school achievement. These

studies demonstrated that students in schools of less than 100

pupils did not achieve as much in certain subjects as pupils in

schools enrolling from 100 to 500 students. Whether or not this

factor played a role in this present study is not known, but it

might well have affected the Indian students.

School Attendance School Attendance

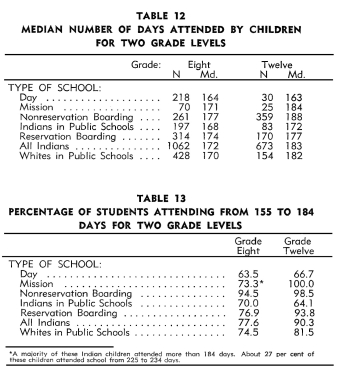

Table 12 shows the median number of days attended by Indian children

in the various schools and by white children in public schools.

Table 13 gives the percentage of Indian children in the various

schools and white children in public schools that attended from

155 to 184 days. It is apparent from these two tables that Indian

children in the non-reservation boarding schools have the best

record of attendance while the Indian children in the day schools

have the poorest record of attendance. However, the attendance

figures as given here for Indian children compare favorably with

those of white children in the public schools in this study. If

attendance is a factor in school achievement, then Indian children

attending non-reservation boarding schools should achieve the

most and Indian children attending day schools

should achieve the least. This is merely an interesting hypothesis,

which might be explored in a study planned to test out the hypothesis.

Males and Females Enrolled Males and Females Enrolled

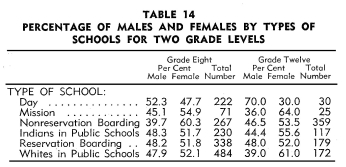

Table 14 indicates the percentage of male and female Indian children

enrolled in the various schools and the percentage of male and

female white children enrolled in the public schools in this study.

These figures would seem to indicate that the schools which Indian

children attend are holding more girls than boys in school. This

trend is more evident with regard to white children in the public

schools. The latest enrollment figures for the nation show that

about 430,000 more girls than boys go to high school, despite the

fact that there are more boys than girls of high school age."15

Academic Ambition Academic Ambition

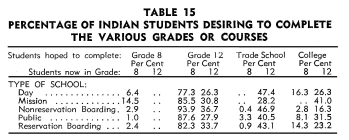

Table 15 indicates the percentage of students desiring to complete

the various grades or courses. The some kind of information was

not available for the white children in the public schools in this

study, but it would be supposed that the academic ambition of the

white children would be higher than that of the Indian children.

Furthermore, it would be supposed that academic ambition would

be a factor in school achievement. Whether or not this factor played

a role in this study is not known.

SUMMARY

A number of factors seemingly related to school achievement have

been cited and discussed. If these factors affected school achievement

as measured in this study, they did so to produce differences in

achievement:

(1) among Indian children attending the different types of schools

or living in different geographic areas, and

(2) of Indian children when contrasted to white children in public

schools.

These factors and many more, tend to operate in two directions.

This complicates rather than simplifies the problem of answering

the question, how well are Indian children educated?

Some of the factors discussed operate in varying degrees of intensity

on different groups of Indian children to produce less school achievement

than that attained by white children in the public schools. Some

of these factors are: degree of Indian blood, language spoken in

the home, home stability, place of residence, kinds of friends,

late entrance to school, size of school attended, regularity of

school attendance, and academic ambition. Any conclusions, therefore,

regarding the school achievement of Indian children as contrasted

to the school achievement of white children in public schools must

be tempered by the fact that these factors may tend to operate

against Indian children. Some may argue that the influence of some

of these factors on school achievement has not been definitely

established. Until research proves differently, we can only be

mindful of the differences in the cultural and educational backgrounds

of Indian children as contrasted to white children in public schools.

3 Peterson. op. cit. p. 27.

4 Peterson, op.cit. p. 29.

5 Peterson, op cit. p. 30.

6 Review and Preview, Secondary School

Studies of Drop-Outs, Hidden Tuition Costs, Junior High Activity

Program.

Lawrence Junior High School, Liberty Memorial High School, Lawrence,

Kansas. (In cooperation with the School of Education, University

of Kansas) 1950-51.

7 Kenneth E. Anderson. A Summary Report

to the North Central Schools of Kansas on Criterion I. (Mimeographed

Bulletin) School

of Education, University of Kansas, 1949, p. 16.

8 Peterson.

op. cit. pp. 31-32.

9 Peterson. op.cit. pp. 33-34.

10 Peterson. op. cit. p. 34.

11 Peterson. op. cit. p. 34.

12 Kenneth F.

Anderson. A Summary Report to the North Central Schools

of Kansas on Criterion 1, p. 13.

13 Kenneth E. Anderson. "A Frontal Attack

on the Basic Problem in Evaluation." Journal of

Experimental Education, 18 (March 1950) 163-174.

14 Jim Schunert. "The

Association of Mathematical Achievement with Certain Factors

Resident in the Teacher, in the Teaching,

in the Pupil and in the School." Journal of Experimental

Education, 19 (March 1951) 219-238.

15 EIIsworth Tompkins. "Where Are the

Boys?" School and Society, 70 (July 2, 1949) 8-10.

|