|

AN ANALYSIS OF ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT

OF INDIAN HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS IN FEDERAL AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

I. INTRODUCTION

The major concern of this longitudinal study was

to determine whether academic achievement differs significantly

for American Indian

students enrolled in four types of schools: (1) federal on-reservation,

(2) federal off-reservation, (3) public on-reservation, (4)

public off-reservation. Other important interests were to examine

differences

in academic achievement by geographic area, grade, and sex.

In addition, it was the purpose of the study to gather a variety

of data on other psychological and sociological variables and

to investigate the relationship of some of them to achievement.

Of the numerous studies that have been made of academic achievement

of American Indian students, only a few have examined levels

of achievement in various types of schools, notably the extensive

study by Coombs who found that Indian students who were enrolled

in public schools achieved at a higher level on the average than

did those enrolled in Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) schools.

However,

since initial individual differences were not controlled statistically,

differences in group achievement could not be attributed to the

educational experiences provided to students by the schools.

Although Coombs was careful to point out that differences in

socioeconomic

backgrounds of the students in the groups being compared may

have accounted for the disparity in achievement levels, it

became almost

axiomatic, as a result of the findings of the study, that an

Indian student would make greater academic progress in a public

school

than in a BIA school. 1

In this present study, individual differences were taken into

consideration in comparing academic achievement of various groups.

To provide

a measure of control of individual differences influencing achievement

the statistical technique of analysis of covariance was employed

so that the differences in achievement could be attributed to

the treatments being tested.

II. METHOD

The Sample

In the fall of 1966 a sample of American Indian high school students

was drawn from 21 schools located in the seven states of Alaska,

Arizona, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and Utah.

Approximately equal numbers were drawn from each of the four school

types: federal on-reservation, federal off-reservation, public

on-reservation, and public off-reservation. The sample was also

stratified on the basis of sex, grade, and geographic area, with

approximately equal numbers of male and female, and with 34% coming

from grade nine, 28% from grade ten, 20% from grade eleven, and

18% from grade twelve. The sample included all Indian students

enrolled in certain schools and a random selection of students

from other schools and was drawn so as to provide representation

from certain Bureau of Indian Affairs administrative areas proportionate

to the numbers of students enrolled in federal schools in those

areas. This sample, numbering 3,346 students, was pretested in

the fall of 1966. In the spring of 1967 testing sessions were held

again in all of the same schools, at which time it proved possible

to obtain usable post-test results for 2,584 of those who had been

pretested in the fall. This group of 2,584 subjects, who were administered

both pretests and post-tests, then comprised the sample for the

first year of the study.

Insufficient time to make necessary arrangements, considering certain

difficulties encountered, made it impossible to include public

school native Alaskan students in the sample for the first year

of the study. However, this situation was corrected and students

enrolled in two public schools were added to the sample for the

succeeding years of the study.

In the fall of 1967 a total of 3,375 Indian students was tested.

Of these, a substantial number were ninth grade students brought

into the sample for the first time, while the others were principally

students who had been tested the previous school year. In the spring

of 1968 a total of 2,556 Indian students was tested. Of this number,

complete and usable data for both the fall pretest and the spring

post-test were obtained for 1,928 Indian students.

The next testing session was held in the spring of 1969. No new

ninth grade students were added to the sample at this time. Data

were sought only on students who had been tested at some prior

time in the study. This, of course, limited the spring of 1969

sample to tenth, eleventh, and twelfth grade students. Data were

obtained for 1,377 students in the 1969 spring testing.

The final testing was accomplished in the spring of 1970, and again

was confined to students who had been tested previously, thus limiting

the sample to eleventh grade and twelfth grade students. Of the

1,377 students tested in the spring of 1969, it was possible to

test 837 again in the spring of 1970.

Measuring Instruments

The following tests were administered during the course of the

study.

Fall 1966

California Achievement Tests (CAT), Advanced, Complete Battery,

1957 Edition, 1963 Norms, Form W.

California Short-Form Test of Mental Maturity (CTMM), 1963 Level

4.

Mooney Problem Check List (Abbreviated Version), Form J-SH.

Questionnaire.

Spring 1967

CAT, Form X.

Fall 1967

CAT, Form Y.

CTMM. Administered to all ninth grade students and to Alaska public

school students, grades 10-12, new to the sample.

Questionnaire. Administered to all ninth grade students and to

Alaska public school students, grades 10-12, new to the sample.

Semantic Differential.

Spring 1968

CAT, Form W.

School Interest Inventory, by William Cottle, published by Houghton

Mifflin Company, 1966.

Spring 1969

CAT, Form X.

California Psychological Inventory. Five measures: CS (Capacity

for Status), SP (Social Presence), AC (Achievement via Conformance),

SA (Self-Acceptance), and AI (Achievement via Independence).

Value Orientation Scale.

Spring 1970

CAT, Form Y.

Vocational Aspiration Scale.

Testing Procedures

Each of the six testing sessions was completed in one day at each

school. All testing each fall was accomplished within a period

of about two weeks during late September and early October. Spring

testing was done during the latter half of April.

In each geographic area testing was under the supervision of a

trained and experienced psychometrician who either administered

the tests or trained and supervised others, all of whom had previous

experience in testing.

Analysis of Data

In comparing groups within the sample on the basis of academic

achievement, post-test California Achievement Test (CAT) raw scores

were used as a criterion and differences in means were tested for

significance by analysis of covariance. Since individual differences

in scholastic aptitude and in academic ability could conceivably

influence criterion scores, pretest intelligence and achievement

scores were used as control variables. The California Test of Mental

Maturity (CTMM) intelligence quotient scores were used as a scholastic

aptitude control, and the pretest California Achievement Test (CAT)

raw scores were used as a prior achievement control.

III. ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT BY SCHOOL TYPES

One-Year Analyses

Since achievement tests were administered at six different points

within a span of four school years it was possible to analyze achievement

for the following one-year periods:

Fall 1966 (pretest) - Spring 1967 (post-test)

Fall 1967 (pretest) - Spring 1968 (post-test)

Spring 1968 (pretest) - Spring 1969 (post-test)

Spring 1969 (pretest) - Spring 1970 (post-test)

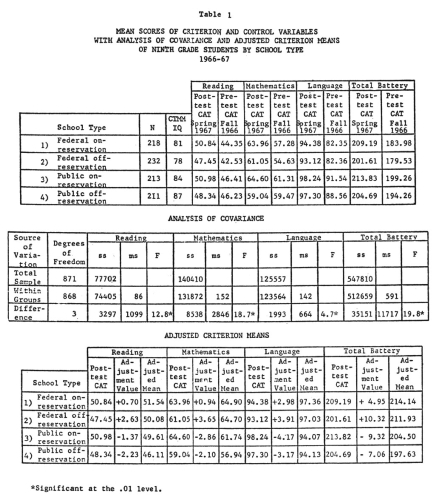

Table 1 presents the mean raw scores of the criterion and control

variables for reading, mathematics, language, and total battery,

by school types, for ninth grade students who were pretested in

the fall of 1966 and post-tested in the spring of 1967. Also presented

in Table 1 are analysis of covariance figures and adjusted criterion

means.

The F scores of 12.82, 18.73, 4.67, and 19.84 with 3 and 868 degrees

of freedom are all significant beyond the 1% level. Therefore,

there is little doubt that the ninth grade students enrolled in

the four types of schools differed significantly in achievement

during the 1966-67 school year. Since significant F values were

found, it is appropriate to compute adjusted criterion means for

each school type. In similar succeeding tables, whenever differences

in criterion means are not found to be significant, adjusted means

are not presented.

In order to avoid burdening the body of the report with tables,

the remaining mean raw scores, analysis of covariance, and, where

appropriate, adjusted criterion means, by grade and school type,

for each of the one-year measurement periods are presented in Tables

A1- A12 in Appendix A.

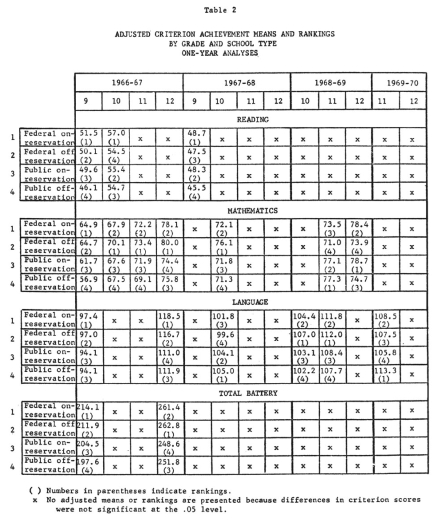

A compilation of the adjusted criterion means found in Table 1

and in Tables A1 - A12 is presented in Table 2. Rankings, by

school types, are indicated in parentheses. Those categories

for which achievement differences between school types were found

not to be a significant (11th grade reading in 1966-67, 12th

grade reading in 1966-67, 10th grade reading in 1967-68, etc.)

are marked with the letter x.

An inspection of Table 2 reveals that significant achievement differences

between school types occurred for only 18 of the 52 categories.

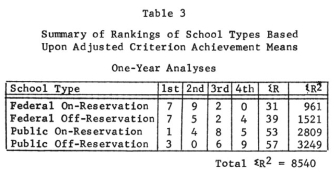

A summary of the rankings appearing in Table 2 is presented in

Table 3. The sums of the ranks (∑R) reveal that the general ranking

of school types from highest to lowest was: federal on-reservation

(31),federal off-reservation (39), public on-reservation (53),

public off-reservation (57).

To test the differences in ranks for significance the Friedman

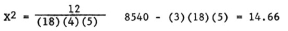

Test, a form of rank order analysis of variance was employed. The

formula is

where k is the number of rankings made (18) and n is the number

of objects being ranked (4).

Then

Reference to an X2 table reveals that

a value of 14.66 with k-1=17 degrees of freedom is not significant

at the .05 level.

To summarize, when individual differences in scholastic aptitude

and academic ability were controlled, significant differences in

one-year academic achievement between school types were found for

only 18 of 52 categories of measurement and differences in the

rankings of school types on those 18 categories were not significant.

Apparently, academic achievement did not differ significantly between

the four types of schools for the one-year time periods.

Two-Year Analyses

Achievement, by school types, was analyzed for the following two-year

spans:

Fall 1966 (pretest) - Spring 1968 (post-test)

Fall 1967 (pretest) - Spring 1969 (post-test)

Spring 1968 (pretest) - Spring 1970 (post-test)

Tables A13 - A20 in the Appendix present the means of criterion

and control variables, analysis of covariance and, where appropriate,

adjusted criterion means, by school types, for each of the two-year

measurement periods.

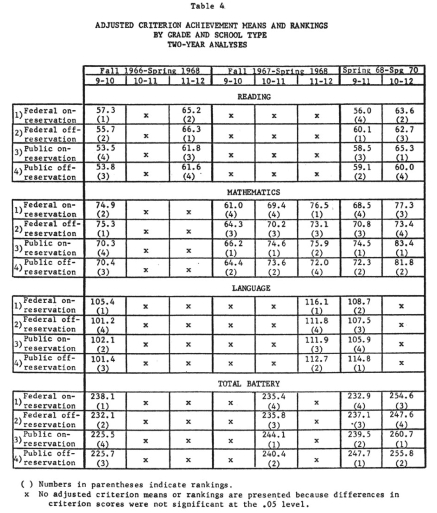

A summary of adjusted criterion achievement means by school types

for two-year periods, taken from Tables A13 - A20 in the Appendix,

is presented in Table 4. Significant differences in achievement

between types of schools were found for 17 of the 32 categories

of measurement, while differences were found not to be significant

for 15 categories.

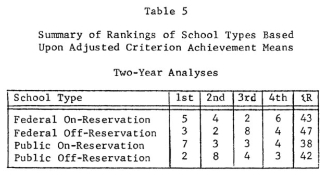

Table 5 presents a summary of the rankings from Table 4. Based

upon the sums of the ranks (∑R) in Table 5, the general ranking

of school types from highest to lowest was: public on-reservation

(38) public off-reservation (42), federal on-reservation (43),

federal off-reservation (47) However, differences in ranks which

obviously are very slight, proved to be non-significant. Use of

the Friedman Test yields an X2 of only 1.44. With 16 degrees of

freedom, this value falls far short of the X2 of 26+ necessary

for significance at the .05 level.

The evidence indicates that when individual differences in scholastic

aptitude and academic ability were controlled there were not significant

differences in two-year academic achievement between school types

for 15 of the 32 categories measured, while for the 17 categories

for which significant differences were found the rankings of school

types were so mixed that no significant pattern of superiority

emerged. Obviously, the two-year analyses do not indicate that

academic achievement differed significantly between the four types

of school.

Three-Year and Four-Year Analyses

Achievement by school types was also analyzed for the following

three-year and four-year spans of time:

Fall 1966 (pretest) -Spring 1969 (post-test)

Fall 1967 (pretest) - Spring 1970 (post-test)

Fall 1966 (pretest) - Spring 1970 (post-test)

Tables A21 - A25 in Appendix A present the means of criterion and

control variables, analysis of covariance and, where appropriate,

adjusted criterion means, by school types, for each of the three-year

measurement periods and for the four-year period.

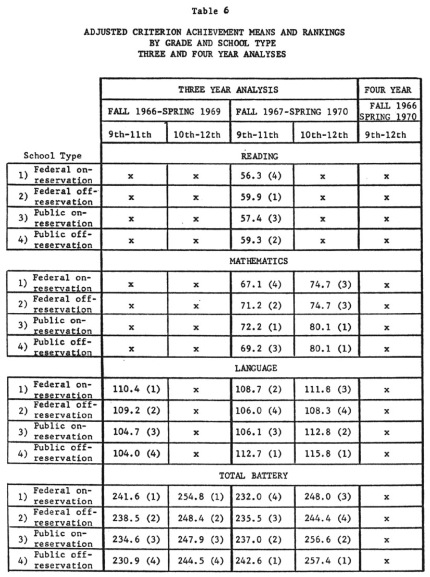

A summary of adjusted criterion achievement means of school types

for three-year and four-year time spans is presented in Table 6.

There were no significant differences in achievement between the

four types of schools for the four-year period from the fall of

1966 to the spring of 1970. The three-year analyses yielded significant

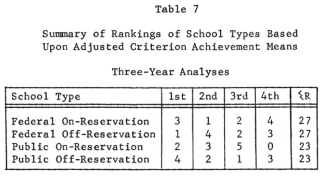

F scores for 10 of the 16 categories. However, the orders of rank

on the 10 significant categories are very mixed and favor the two

public school types only slightly, as can be seen by reference

to the sums of the ranks in Table 7.

Testing the differences in ranks for significance with the Friedman

Test yields an X2 of only 0.96, which falls far short of the figure

of 16.9 necessary for significance at the .05 level. Since differences

in achievement between the four school types were found to be non-significant

for 6 categories and the ranks of the school types did not differ

significantly on the 10 categories for which significant achievement

differences were registered, it appears that academic achievement

did not differ significantly between types of schools during the

three-year periods.

Summary of Analyses of Academic Achievement by School Types

On the basis of adjusted criterion means, which were calculated

for those categories having significant differences, federal schools

ranked higher than public schools on one-year analyses, public

on-reservation schools ranked highest and federal off-reservation

schools lowest by small margins on two-year analyses, and public

schools ranked slightly higher than federal schools on three-year

analyses. However, rankings of school types were so mixed on those

categories for which significant differences were found that differences

in ranks were not significant for one-year, two-year, or three-year

analyses. No significant differences in achievement between the

four types of schools were found for the four-year period.

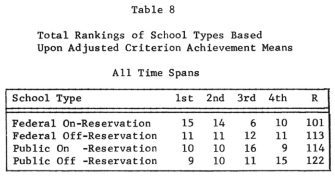

Altogether, the four types of schools were compared on 104 measures

of academic achievement. Of this total of 104 categories of measure,

differences in achievement between school types were found to be

significant at the .05 level of confidence for only 45 categories.

The rankings of the four school types on the 45 significant categories

are shown in Table 8, which is a composite of Tables 3, 5, and

7.

Applying the Friedman Test to the data in Table 8 yields an X2 of 3. With 44 degrees of freedom this falls far short of the X2 of 60+ necessary for significance at the .05 level.

In summary, significant differences in achievement between types

of schools were found for less than one-half of the categories

measured and no significant hierarchal pattern of achievement emerged

for those categories where significant differences in achievement

did exist. The evidence, therefore, does not indicate that the

academic achievement of American Indian students was superior or

inferior in any particular type of high school when individual

differences in scholastic aptitude and academic ability were controlled.

IV. ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT BY AREAS

Analyses of academic achievement by geographic areas also were

made, similar to the analyses of achievement completed for school

types. One-year, two-year, three-year, and four-year analyses

were made.

Designated areas correspond to Bureau of Indian Affairs administrative

areas and include the following: Aberdeen, Muskogee, Navajo, Phoenix,

and Juneau. The numbers of students drawn from each area were based

upon the numbers of students from the area enrolled in BIA schools.

Therefore, as might be expected, numbers of subjects varied greatly

for the different areas.

In testing differences in achievement between areas by analysis

of covariance, post-test achievement scores were used as the criterion

and pretest achievement and intelligence scores were used as control

variables, just as they were in analyzing achievement by school

types.

One-Year Analyses

Achievement by areas was analyzed for the following one-year periods:

Fall 1966 (pretest) - Spring 1967 (post-test)

Fall 1967 (pretest) - Spring 1968 (post-test)

Spring 1968 (pretest) - Spring 1969 (post-test)

Spring 1969 (pretest) - Spring 1970 (post-test)

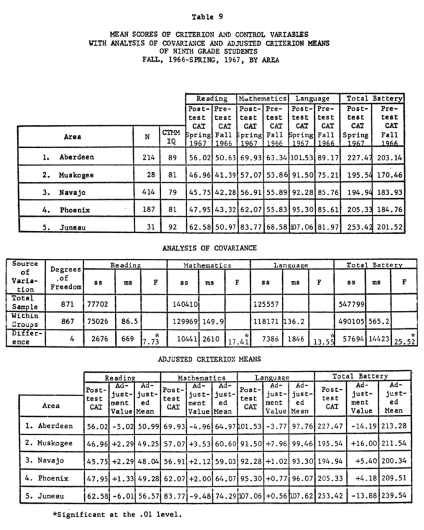

Table 9 presents the means of criterion and control variables,

analysis of covariance, and adjusted criterion means, by areas,

for ninth grade students who were pretested in the fall of 1966

and post-tested in the spring of 1967. The remaining data for one-year

analyses of academic achievement by areas are presented in Tables

B1 - B12 in Appendix B.

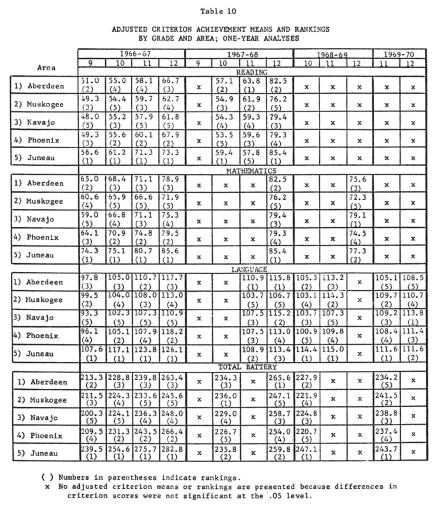

A compilation of the adjusted criterion means gathered from Table

9 and Tables B1 - B12 is presented in Table 10. Rankings by areas

are indicated in parentheses, and categories for which significant

differences in achievement were not found are marked with the letter

x.

A study of Table 10 reveals that achievement differences between

the five areas were found to be significant for 31 of the 52 categories.

Based upon the adjusted criterion mean scores for the 31 categories

for which significant differences were found, the Juneau area ranked

first in 24 of 31 categories. A summary of the rankings from Table

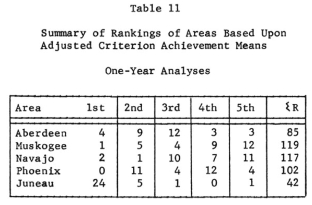

10 is presented in Table 11. On the basis of sums of ranks (?R),

the Juneau area ranked highest by a wide margin (42), Aberdeen

ranked second (85), followed in order by Phoenix (102), Navajo

(117), and Muskogee (119).

Using the Friedman Formula to test differences in ranks for significance

yields an X2 value of 50.42. With 30 degrees of freedom, 50.42

is significant at the .05 level, indicating that achievement differed

significantly between areas on one-year analyses.

Two-Year Analyses

Achievement by areas was analyzed for the following two-year periods:

Fall 1966 (pretest) - Spring 1968 (post-test)

Fall 1967 (pretest) - Spring 1969 (post-test)

Spring 1968 (pretest) - Spring 1970 (post-test)

Tables B13 - B20 in Appendix B present the means of criterion and

control variables, analysis of covariance, and, where appropriate,

adjusted criterion means, by areas, for each of the two-year measurement

periods.

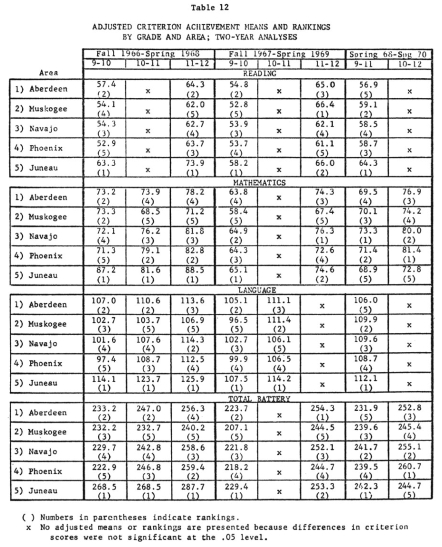

A summary of adjusted criterion achievement means by areas for

two-year intervals is presented in Table 12. An inspection of the

table reveals that differences in achievement between areas were

found to be significant for 25 of the 32 categories, while for

only 7 categories were differences found non-significant. Again,

as was true for the one-year analyses, the Juneau area ranked first

by a large margin, followed by Aberdeen. Next in order were Navajo,

Phoenix, and Muskogee.

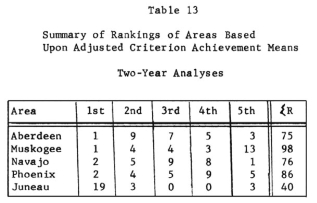

A summary of the rankings from Table 12 appears in Table 13. On

the basis of sums of ranks (∑R), the Juneau area ranked highest

(40), Aberdeen and Navajo were second (75 and 76), followed by

Phoenix (86) and Muskogee (98).

Application of the Friedman Test

for differences in ranks yields an X2 value of 30.01, which is

not significant at the .05 level with 24 degrees of freedom.

Thus, analyses indicate that achievement did not differ significantly

between areas for the two-year measurement periods.

Three-Year and Four-Year Analyses

Analysis of achievement by areas was also analyzed for the following

three-year and four-year spans of time:

Fall 1966 (pretest) - Spring 1969 (post-test)

Fall 1967 (pretest) - Spring 1970 (post-test)

Fall 1966 (pretest) - Spring 1970 (post-test)

Tables B21 - B25 in Appendix B present the means of criterion and

control variables, analysis of covariance and, where appropriate,

adjusted criterion means, by areas, for each of the three-year

time spans and for the four-year period.

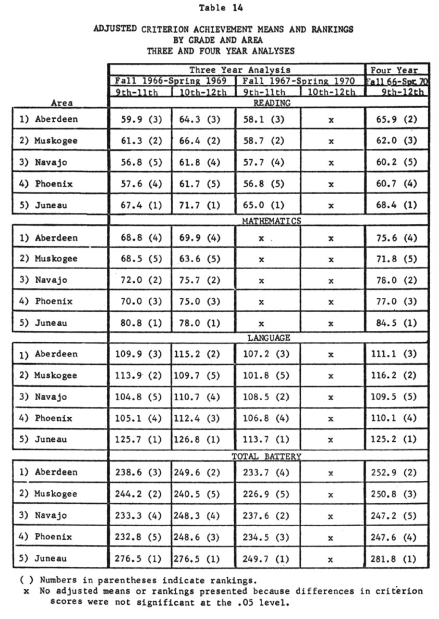

A summary of adjusted criterion means by areas for three-year and

four-year time spans are presented in Table 14. Differences in

achievement for the areas were significant for 11 of the 16 three-year

categories and for all 4 of the four-year categories. Juneau ranked

first in every three-year category, and was followed in order in

overall rankings by Aberdeen, Navajo, Muskogee, and Phoenix.

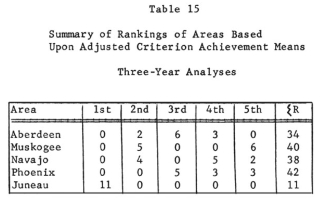

A summary of rankings from Table 14 for three-year analyses is

presented in Table 15. On the basis of sums of ranks the order

of rank from highest achievement to lowest is: Juneau, Aberdeen,

Navajo, Muskogee, and Phoenix.

The Friedman Test yields an X2 of 23.27, which is significant at

the .O1 level with 10 degrees of freedom, indicating that differences

in achievement between areas were significant for the three-year

measurement periods.

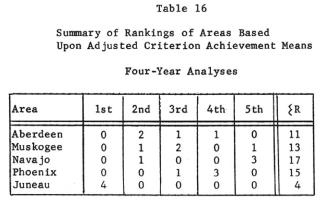

A summary of rankings from Table 14 for the four-year analyses

is shown in Table 16. On the basis of sums of ranks it can be seen

that achievement was highest in the Juneau area, followed in order

by Aberdeen, Muskogee, Phoenix, and Navajo.

Computation of X2 by the Friedman Formula gives a value of 10,

which is significant at the .05 level. Achievement of Indian

students in the five areas seemed to differ significantly over

the four-year measurement period.

Summary of Analyses of Academic Achievement by Areas

Based upon adjusted criterion means, the Juneau area ranked first

and the Aberdeen area second for every time span. Rankings for

the three other areas varied for the different measurement periods.

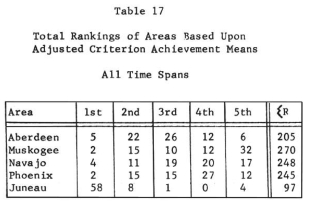

Of the total of 104 categories on which achievement was measured,

differences in achievement between areas were found to be significant

at or beyond the 5% level of confidence for 71, or more than two-thirds,

of the categories. Rankings based upon all 71 categories are presented

in Table 17, which is a composite of Tables 11, 13, 15, and 16.

Applying

the Friedman Test to the data in Table 17 yields an X2 of 107.14.

With 70 degrees of freedom this value is significant at the .O1

level of confidence.

In summary, when individual differences in scholastic aptitude

and academic ability were controlled, differences in achievement

between areas appeared to be significant, with the Juneau area

ranking highest, followed by Aberdeen. No clear pattern of superiority

emerged for the other three areas.

V. ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT BY GRADE AND SEX

Academic Achievement by Grades

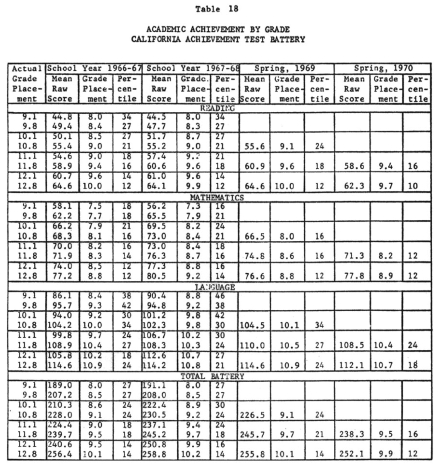

Academic achievement data for each grade are presented in Table

18. While it is evident that academic achievement of Indian students,

as measured by the California Achievement Test, is progressive

from grade 9 through grade 12, it is also evident that achievement

is regressive when compared to national norms. For example, the

difference in grade placement in reading for students at the actual

9.1 grade level and those at the 12.8 grade level was 2 grades

rather than the 3.7 grades considered normal. For mathematics the

grade placement differences were even smaller, registering 1.3

grades for the 1966-67 school year and 1.9 grades for the 1967-68

school year. Language showed somewhat greater differences, with

2.5 grades for 1966-67 and 2 grades for 1967-68. In comparing actual

grade placement with achievement grade placement as measured by

the California Achievement Total Battery mean scores, it is seen

that Indian students were about one year retarded academically

when entering ninth grade but were more than two and one-half years

retarded when about to graduate from high school.

Percentile rankings demonstrate this progressive retardation very

strikingly. Based upon total battery mean scores, ninth grade students

ranked at percentile 27, while twelfth grade students ranked at

percentile 14. Similar regression occurred for each of the separate

subject areas. Scores were consistently highest in language and

lowest in mathematics.

Academic Achievement by Sex

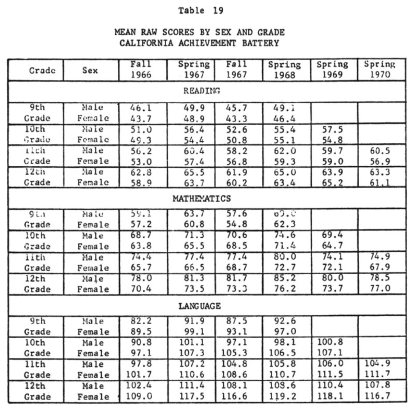

When achievement scores are compared by sex, it can be seen from

an inspection of Table 19 that boys consistently scored slightly

higher than girls in reading and considerably higher than girls

in mathematics, while girls consistently scored substantially higher

than boys in language. Attesting to the consistency of the above

achievement pattern is the fact that the only exception to the

pattern in the 63 comparisons presented in Table 19 was for 12th

grade reading in the spring of 1969 testing.

The evidence clearly indicates superiority of Indian boys over

girls in the mastery of reading and mathematics skills and the

superiority of girls over boys in the mastery of English language

skills.

VI. RESPONSES TO OTHER MEASUREMENT INSTRUMENTS

Responses to Questionnaire

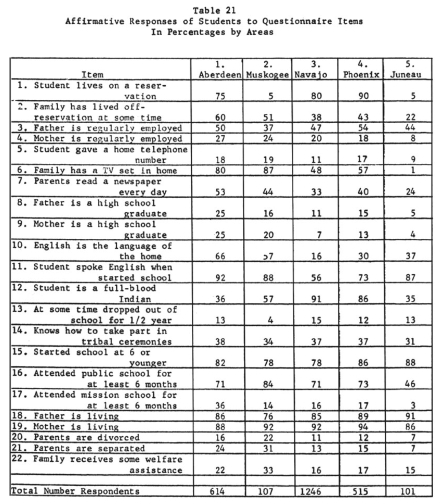

Each student was asked to respond to a questionnaire as a means

of obtaining personal and familial data. Total affirmative responses

to each question are presented in percentage form for each school

type in Table 20, and for each area in Table 21.

Student responses to the questionnaire, as presented in Table 20,

indicate that higher percentages of public high school than federal

high school students have telephones, TV sets, and daily newspapers

in the home. Also, more started school at six years of age or younger,

more of their parents are high school graduates, more of their

parents are regularly employed, and fewer students know how to

take part in tribal ceremonies.

Public off-reservation schools had the highest percentage in whose

homes English is the primary language, as well as the highest percentage

who spoke English when they started school. Public on-reservation

schools had the highest percentage of students residing on a reservation.

When questionnaire responses are tabulated by areas, as presented

in Table 21, certain differences and similarities between areas

become evident. Some of these that seem most apparent are:

1. A majority of Indian high school students in the Aberdeen (75%),

Navajo (80%), and Phoenix (90%) areas live on reservations, while

very few in the Muskogee (5%) and Juneau (5%) areas do.

2. Only 1°/ of the students tested in the Juneau area

claimed to have a TV set at home, while substantial numbers

in other areas,

ranging from 48 percent in the Navajo to 87 percent in the

Muskogee areas, claimed them.

3. The Juneau and Navajo areas ranked lower than other areas in

telephones, daily newspapers, parents who graduated from high school,

parents divorced or separated, and families receiving welfare assistance.

4. The Navajo area has much the lowest percentage of homes in which

English was the primary language (16%), and in percentage of students

who spoke English when they started school (56%), while Aberdeen

was highest in both categories (66%, 92%).

5. The Navajo area had the highest percentage who had dropped out

of school for 1/2 year or more (15%), and the Muskogee area the

lowest (4%).

6. The Navajo area ranked highest in percent of full-blood Indian

students with 91 percent, followed closely by the Phoenix area

at 86 percent.

7. The Muskogee area had the lowest percentage of fathers regularly

employed (37%) and Phoenix the highest (54%), while the Juneau

area had the lowest percentage of employed mothers (8%) and the

Aberdeen area the highest (27%).

8. Knowledge of how to take part in tribal ceremonies seems to

differ little from one area to another, ranging only from a low

of 31 percent in the Juneau area to a high of 38 percent in the

Aberdeen area.

Questionnaire responses by grade were also tabulated but are not

presented because of the similarity of responses from grade to

grade. For the same reason, it did not seem profitable to present

responses by sex.

Responses to Mooney Problem Check List

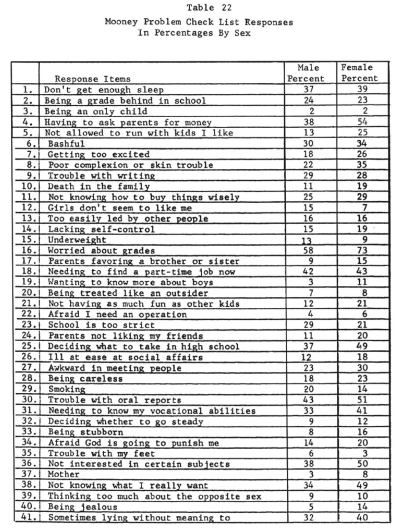

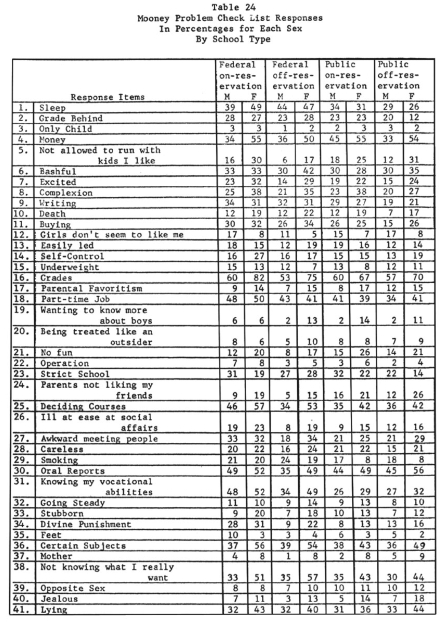

Tables 22-25 present responses of students to the abbreviated version

of the Mooney Problem Check List administered in this study. Students

were asked to check each item that they felt described a problem

for them. Figures in the tables are percentages of all students

in each category who checked the particular item.

Table 22 reveals that more Indian high school students-of both

sexes were concerned about grades than about any other problem

listed. This item, number 16, was checked most frequently, both

by boys (58%) and by girls (73%). It is interesting to note that

the sexes agreed on the ten problems that troubled them most, although

not always in the same order of rank. The other items ranking in

the toy ten, in order of total frequency checked, are: (30) oral

reports, (4) having to ask parents for money, (36) not interested

in certain subjects, (25) deciding what to take in high school,

(18) needing to find a part time job now, (38) not knowing what

I really want, (1) not getting enough sleep, (31) needing to know

my vocational abilities, and (41) lying without meaning to.

Other items which ranked high in frequency of responses for both

sexes were: (6) bashful, (9) trouble with writing, (11) not knowing

how to buy things wisely, and (27) awkward in meeting people.

Girls also checked frequently: (8) poor complexion or skin trouble,

and (7) getting too excited. Apparently girls felt that they had

more problems than did boys, since 32 of the 41 items were checked

by a higher percentage of girls than boys. However, the following

problems seemed to concern more boys than girls: (23) school too

strict, (29) smoking, (12) girls don't seem to like me, and (15)

underweight.

Those problems checked least frequently were: (3) being an only

child, (35) trouble with my feet, (22) afraid I may need an operation,

(37) Mother, (19) wanting to know more about boys, and (2) being

treated like an outsider.

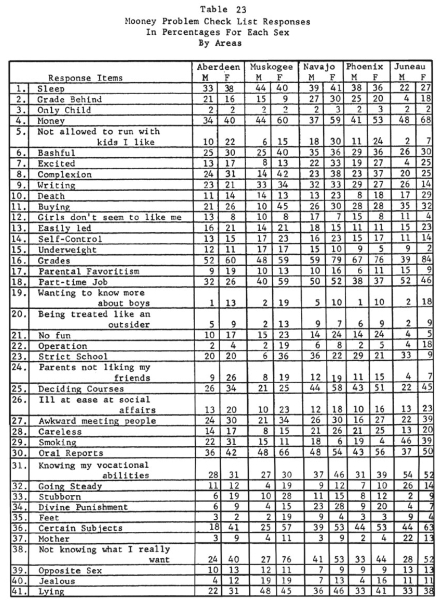

The following are some observations based upon inspection of Table

23:

1. In the Juneau area, parents not liking students' friends (24),

and not being allowed to run with certain friends (5) are not as

frequent problems as for students of other areas.

2. A higher percentage of Juneau area students found smoking (29)

and needing to know their vocational abilities (31) to be causes

for concern than did students of other areas.

3. Higher percentages of students in the Navajo area, with Phoenix

running a close second, checked the following items: (2) being

a grade behind in school, (7) getting too excited, (25) deciding

what to take in high school, and (34) afraid God is going to punish

me.

In making comparisons of Mooney data between school types it can

be seen in Table 24 that higher percentages of students in federal

schools than in public schools considered the following items to

be problems: (1) don't get enough sleep, (2) being a grade behind

in school, (9) trouble with writing, (25) deciding what to take

in high school, (29) smoking, (32) needing to know my vocational

abilities, and (38) not knowing what I really want. It is interesting

that students in federal on-reservation schools checked about twice

as frequently as other students item 34, "afraid that God

is going to punish me." They also checked item 22 more frequently, "afraid

I may need an operation."

Public school off-reservation students checked less frequently

than others item 23, "school is too strict."

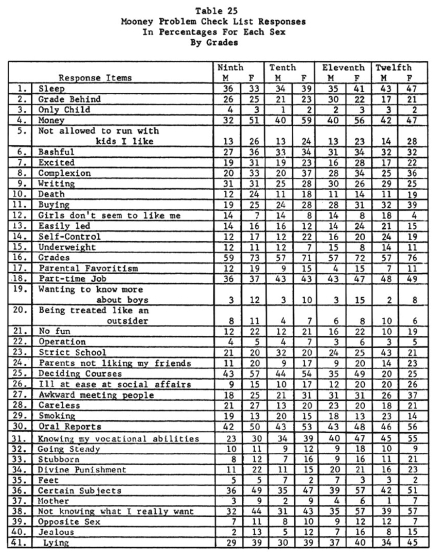

In examining Mooney data by grades there are a number of problems

that seem to become increasingly critical as students progress

from grade 9 through grade 12. As can be seen from inspection of

Table 25 these problems are: (1) don't get enough sleep, (11) not

knowing how to buy things wisely, (18) needing to find a part-time

job now, (26) ill at ease at social affairs, (27) awkward in meeting

people, (31) needing to know my vocational abilities, and (38)

not knowing what I really want. Other problems seem to remain at

a relatively consistent level, with one rather interesting and

striking exception being the relatively high percentage of twelfth

grade males who considered item 23, "school is too strict," a

problem.

It is possible to analyze the Mooney Problem Check List responses

by problem areas, as well as by individual responses. Items may

be grouped together into seven problem areas. When total responses

made to all items in a problem area are figured as percentages

of total possible responses for all items in that problem area

and this is done for each of the seven areas, it is possible to

see the areas of greatest concern. The general problem areas, with

percentages of items that were checked for each problem area, are

as follows:

| I. |

Health and Physical Development (1, 8, 15, 22, 29, 35) |

17.3% |

| II. |

School (2, 9, 16, 23, 30, 36) |

38.3% |

| III. |

Home and Family (3, 10, 17, 24, 37) |

8.8% |

| IV. |

Money, Work, the Future (4, 11, 18, 25, 31, 38) |

39.8% |

| V. |

Boy and Girl Relations (5, 12, 19, 26, 32, 39) |

12.1% |

| VI. |

Relations to People in General (6, 13, 20, 27, 33, 40) |

18.5% |

| VII. |

Self-Centered Concerns (7, 14, 21, 28, 34, 41) |

21.7%

|

Problems of greatest concern to Indian high school youth appear to be in areas

IV and II, having to do with money, work, the future, and school. Next appear

to be those concerning self (VII) and relations to people (VI). Of least concern

seem to be problems of home and family.

The Semantic Differential

A Semantic Differential was administered in the fall of 1967. In this instrument

students were asked to react to ten concepts: SCHOOL, TEACHERS, MY SUCCESS

IN SCHOOL, MYSELF AS A PERSON, INDIAN, WHITE MAN, MY PRESENT LIFE, MY FUTURE,

EDUCATION, COLLEGE. Under each concept, twelve bipolar seven-point scales,

using adjective pairs, were presented, three for each of four major factors.

The four major factors and their opposite adjective pairs were as follows:

Evaluation (cognitive)?good-bad, valuable-worthless, important-unimportant;

Evaluation (affective)?pleasant-unpleasant, ugly-beautiful, nice-awful; Potency?weak-strong,

shallow-deep, influential-powerless; Activity?fast-slow, busy-idle, active-passive.

The following is the general format used:

SCHOOL

1. Good ==== ==== ==== ==== ==== ==== ==== Bad

2. Weak ==== ==== ==== ==== ==== ==== ==== Strong

etc.

Each scale was scored as follows:

|

|

7

|

6

|

5

|

4

|

3

|

2

|

1

|

Unpleasant

|

|

|

===

|

===

|

===

|

===

|

===

|

===

|

===

|

|

A score of 1 on the above scale indicates a rating of very unpleasant, 2 -

quite unpleasant, 3 - slightly unpleasant, 4 - neutral, 5 - slightly pleasant,

6 - quite pleasant, 7 - very pleasant.

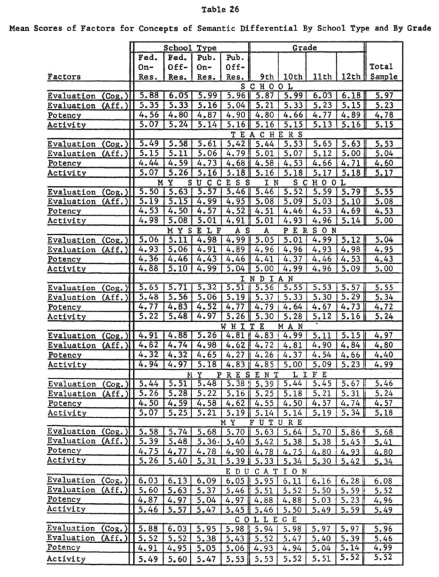

Table 26 presents mean scores of factors under each of the concepts for school

types and also for each grade. The score for each factor was derived by averaging

the mean scores of the factor's three scales.

Comparing Semantic Differential Scores by Concepts

A comparison of total sample mean scores for the various concepts

in Table 26 reveals that Indian high school students have a high

regard for education. EDUCATION was given the highest overall rating

of the ten concepts with highest mean scores on both of the Evaluation

factors and second highest on the Potency and Activity factors.

COLLEGE was rated second highest overall, with the third highest

score on Cognitive Evaluation, second highest on Affective Evaluation,

and top scores on Potency and Activity. SCHOOL was rated second

highest on the Cognitive Evaluation factor, but only sixth on Affective

Evaluation. Apparently, school was liked less than it was valued.

Overall rankings of the ten concepts, from highest to lowest, with

ratings on each factor shown in parentheses, were as follows:

EDUCATION (1,1,2,2); COLLEGE (3,2,1,1); MY FUTURE (4,3,3,3);

INDIAN

(5,4,5,4); SCHOOL (2,6,4,7); MY PRESENT LIFE (8,5,7,5);

TEACHERS (7,8,6,6); MY SUCCESS IN SCHOOL (6,7,8,8);

MYSELF (9,9,9,9); WHITE MAN (10,10,10,10).

As can be seen, there was great consistency in factor ratings.

When subjected to Friedman's rank order of analysis test it was

found that differences between concept ratings were significant

at the .O1 level of confidence.

Apparently, Indian students were quite optimistic about their future,

since they rated the concept MY FUTURE third highest. However,

a comparatively low self-concept is indicated by the next to last

rating of MYSELF AS A PERSON on all four factors. The concept WHITE

MAN scored lowest on every factor.

Comparing Semantic Differential Scores By School Types

Differences between ratings assigned to the concepts by the four

school types proved to be significant beyond the .05 level of confidence

for only three of the ten concepts -- INDIAN, WHITE MAN, and MY

FUTURE.

Federal off-reservation school students gave INDIAN a higher rating

on every factor than did students of the other types of schools.

Federal on-reservation school students rated INDIAN next highest,

public-off reservation students next, and public on-reservation

students rated INDIAN lowest on every factor. With only one exception,

federal schools in the study are segregated, while all public schools

are integrated. Apparently, Indian students attending all-Indian

schools hold a higher opinion of Indians than do those in integrated

school situations.

Public on-reservation school students rated WHITE MAN higher than

did other students on every factor, federal on-reservation students

rated WHITE MAN next highest overall, federal off-reservation next

to lowest overall, and public off-reservation students lowest on

every factor. Those students attending school on reservations in

an Indian dominated society tended to rate WHITE MAN higher than

did those attending school off-reservation in the white man's world.

On the concept MY FUTURE, federal off-reservation school students

scored highest overall, followed in order by public off-reservation,

public on-reservation and federal on-reservation. Apparently, off-reservation

Indian students are more optimistic about the future than are on-reservation

students.

Comparing Semantic Differential Scores By Grades

Based upon scores on all factors, differences between the ratings

of ninth, tenth, eleventh, and twelfth grade students were significant

for three of the ten concepts--WHITE MAN, MY PRESENT LIFE, and

EDUCATION. For each of the three concepts, ratings tended to

be higher for

each successively higher grade.

When the Cognitive Evaluation factor scores are examined by themselves,

the pattern of progressively higher scores for each successive

grade is noticeable for all concepts except MYSELF AS A PERSON,

INDIAN, and COLLEGE. However, scores on Affective Evaluation do

not show the same increase. As Indian students progress through

high school it appears that they place an increasing value on school,

teachers, education, their success in school, their present life,

their future, and white people, but experience no increased positive

feeling toward them.

Scores on Potency and Activity factors vary only little by grades

for most concepts. Exceptions are increases in Activity ratings

for WHITE MAN, and in Potency ratings for WHITE MAN, EDUCATION,

and COLLEGE.

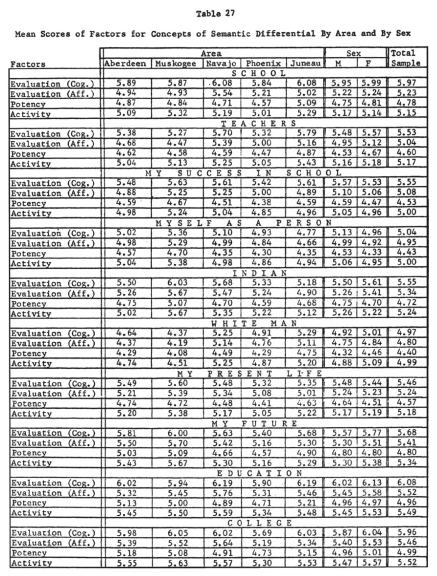

Comparing Semantic Differential Scores By Areas

Semantic Differential scores are presented by areas in Table 27.

Ratings by the Indian students in the five geographic areas differed

significantly on every concept except SCHOOL. The following are

some observations on the ratings:

1. The Juneau area gave TEACHERS and WHITE MAN the highest ratings,

followed closely in each case by the Navajo area. The lowest ratings

were given these two concepts by the Muskogee area. The Aberdeen

area also rated WHITE MAN very low, with next to lowest scores

on all four factors.

2. The Muskogee area rated INDIAN highest and the Juneau area rated

INDIAN lowest.

3. Muskogee area students seemed to evidence greater self-esteem

and confidence than students in other areas by registering the

highest scores on all factors for MY SUCCESS IN SCHOOL, MYSELF

AS A PERSON, INDIAN, and MY FUTURE. The Muskogee area also scored

highest on three factors and second on the fourth factor for the

concept MY PRESENT LIFE.

4. The Aberdeen area scored high on MYSELF AS A PERSON, MY PRESENT

LIFE, and MY FUTURE, ranking second to Muskogee on each concept.

5. The Phoenix area rated the following concepts lower than did

the other areas: MY SUCCESS IN SCHOOL, MY PRESENT LIFE, MY FUTURE,

EDUCATION, and COLLEGE.

6. The Navajo and Juneau areas rated EDUCATION higher than did

the other three areas.

7. COLLEGE was rated highest by the Muskogee area.

Comparing Semantic Differential Scores By Sexes

It is evident in Table 27 that females generally rated the concepts

higher than did males. Girls rated TEACHERS, WHITE MAN, EDUCATION,

and COLLEGE higher on every factor, and SCHOOL and MY FUTURE higher

on three of the four factors. Exceptions to the general trend appear

for the concepts MY SUCCESS IN SCHOOL and MYSELF AS A PERSON, which

were rated higher by boys than by girls on all four factors, and

MY PRESENT LIFE, which was rated higher by boys on three factors.

Indian boys seem to have a better self-concept and greater confidence

in themselves than do girls, but may have less optimism about the

future.

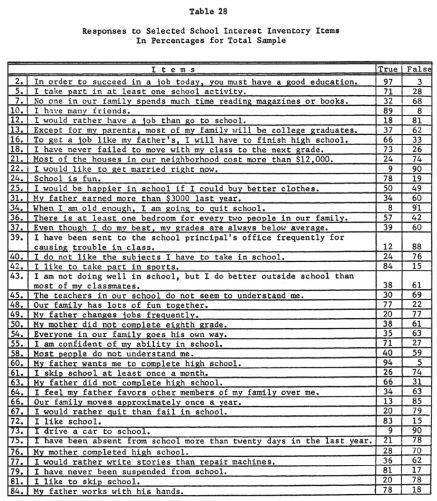

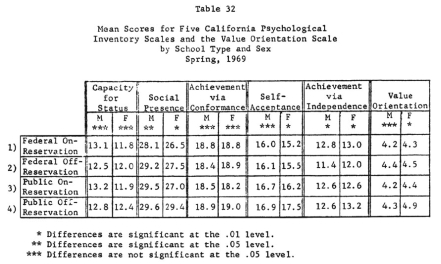

Responses to School Interest Inventory

In the spring of 1968 the School Interest Inventory was administered

to 2164 Indian high school students. On this instrument each student

was asked to respond to 150 statements by marking them true or

false. Table 28 presents percentages of true and false responses

to certain items that have been selected for presentation because

of their information value. Some of the items presented in Table

28, like numbers 31 and 73, are not used in scoring the tests but

do provide valuable personal and familial data. Other items, like

numbers 8 and 93, are meaningful for individuals but not for group

analysis, and are omitted. Item numbers in Table 28 correspond

to item numbers in the instrument. It will be noted that the percentages

do not always add to 100 percent, because some items received no

response from a small percentage of students.

Comparing School Interest Inventory Scores by School

Types and Areas

The School Interest Inventory can be scored to obtain either weighted

or unweighted totals. The weighted method, which assigns values

of 1 to 9 for each item, is used in this study. Boys and girls

are scored on different scales and, therefore, their scores are

not comparable. The scale for boys contains 90 items and has a

potential total score of 375, while the scale for girls has 86

items and a potential score of 337. There are 72 items common to

both scales. Some items in the Inventory are not used for scoring

on either scale.

As in golf and cross-country, the lower score is the better score.

High scores on the School Interest Inventory indicate lack of interest

in school and high probability of dropout. In this study, mean

weighted scores are used to compare the interest in school of Indian

students in different types of schools and in different geographic

areas. These scores are presented in Table 29. Since scores registered

by boys and girls are not comparable they are presented separately.

Inspection of Table 29 reveals that the mean scores for males differ

considerably for the four school types and also for the five areas,

while female scores for areas differ somewhat less than do male

scores, and differ even less for school types. To test the differences

for significance, analysis of variance was used. The results are

presented in Table 30.

Interest in school, as measured by the School Interest Inventory,

differed significantly for boys in the four types of school, with

those in public on-reservation schools registering the greatest

interest and those in federal on-reservation schools the least.

Differences were also significant for boys in the five geographic

areas, with those in the Aberdeen area registering the greatest

interest in school and those in the Navajo area the least.

Differences for girls by school types were not significant. However,

differences for girls by areas were significant, with those in

the Juneau area registering the greatest interest and those in

the Phoenix area the least.

When male and female scores are considered together and a combined

ranking is determined for school types, the order from greatest

interest to least interest is as follows: public on-reservation,

public off-reservation, federal off-reservation, federal on-reservation.

Similarly, the order for areas is as follows: Juneau, Aberdeen,

Phoenix, Navajo, Muskogee. It is interesting that the order of

rank of areas on the School Interest Inventory is identical to

the academic achievement ranking appearing in Table 17.

There are no tables of normative data for the School Interest Inventory.

However, some comparison can be made of mean scores for Indian

students in this study with mean scores for non-Indian students

in other studies. A study in one high school found that the mean

weighted score for male students who stayed in school was 51.98,

while the mean weighted score for male students who later dropped

out was 116.52. For females the scores were 56.91 for stay-ins

and 103.77 for dropouts. A study of students in four other schools

found mean scores of 72.69 for male stay-ins, 137.20 for male dropouts,

60.49 for female stay-ins, and 110.02 for female dropouts.1

It is evident from the above figures that mean scores for Indian

students tend to run high, almost approaching dropout levels. This,

of course, is consistent with the high dropout rates for Indian

students, which have been found to be 39 percent in the Southwest2

and 48 percent in the Northwest3 from enrollment in grade eight

to graduation from high school.

The School Interest Inventory has proved to be a useful instrument

for identifying potential school dropouts. However, its value with

American Indian students was not known. In the interests of investigating

the predictive value of the SII for Indians some further analyses

were attempted on a small scale.

Since the SII was administered in the spring of 1968, those students

who were enrolled in grade nine at that time normally would have

graduated in the spring of 1971. Computer printouts of names of

ninth grade students who had taken the SII in 1968 were mailed

to selected schools with the request that the students listed be

identified as graduates, dropouts, or transfers. Unfortunately,

some school officials were unable to classify a majority of those

who had withdrawn as either definite dropouts or transfers, and

a fourth classification of "unknown" was added. Furthermore,

as no attempt was made to follow-up those who were identified as

transfers, it was not possible to determine whether they were eventually

dropouts or graduates.

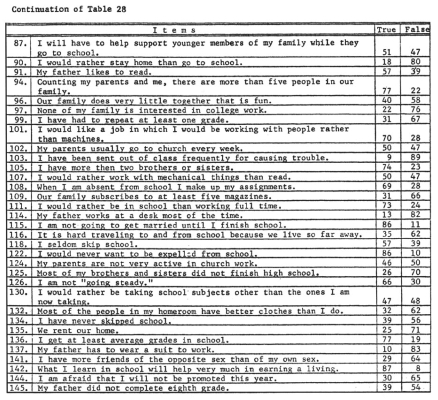

Responses were received from four BIA schools and six public schools

as widely scattered in location as Alaska, Arizona, Utah, New Mexico,

Oklahoma, Nebraska, and South Dakota. Table 31 shows the number

of students in each classification and the average weighted score

registered on the SII by the students so classified.

It is evident from the average scores in Table 31 that the SII

does discriminate to some degree between Indian graduates and dropouts.

However, an examination of single scores leads one to the conclusion

that identification of dropouts on an individual basis would be

difficult.

An inspection of test items reveals some that seem inappropriate

for Indians. An item analysis was made of the responses of the

graduates and dropouts to determine which items seem to discriminate

and which do not. Some items that discriminate between graduates

and dropouts for the general school population but do not for Indian

students are the following:

4. I have more than one older brother or sister.

16. To get a job like my fathers I will have to finish high school.

30. My parents are active in community affairs.

33. My mother does a lot of church work.

47. I like love scenes on television.

50. My mother did not complete eighth grade.

63. My father did not complete high school.

76. My mother completed high school.

84. My father works with his hands.

94. Counting my parents and me, there are more than five people

in my family.

141. I have more friends of the opposite sex than of my own sex.

145. My father did not complete eighth grade.

Other discrepancies appeared in responses by boys to questions

about clothes and by girls to questions about age. Items 25 and

132, "I would be happier in school if I could buy better clothes;" and "Most

of the people in my homeroom have better clothes than I do;" did

not discriminate for Indian boys, although they did for girls.

Also, items 88, 93 and 138, "I am one of the oldest in my

homeroom;" "Most of my friends are older than I;" and "I

am older than most of the people in my class;" did not discriminate

for Indian girls, although they did for boys.

Among the items that seem to discriminate for Indian students but

do not for others are the following:

6. It would be more fun to go to an art gallery than to a showing

of new cars (Indian graduates tended to answer this "true",

and dropouts to answer it "false."

31. My father earned more than $3000 last year.

52. I am not at ease with others.

140. My mother encourages me to do well in school.

It appears that the School Interest inventory could be a useful instrument

for identifying high dropout risks among Indian students if some modifications

were made in scoring based on the item analysis of responses of dropouts and

graduates.

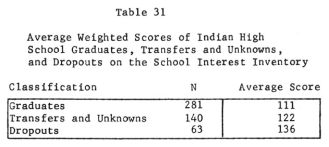

The California Psychological Inventory and the Value Orientation Scale

Five measures from the California Psychological Inventory (CPI) were used:

CS (Capacity for Status), SP (Social Presence), AC (Achievement via Conformance),

SA (Self-Acceptance), and AI (Achievement via Independence). According to the

test manual these measures were designed to assess characteristics of personality

as described below.

CS To serve as an index of an individual's capacity for status (not his actual

or achieved status). The scale attempts to measure the personal qualities that

underlie and lead to status.

SP To assess factors such as poise, spontaneity, and self-confidence in personal

and social interaction.

AC To identify those factors of interest and motivation that facilitate achievement

in any setting where conformance is a positive behavior.

SA To assess factors such as personal worth, self-acceptance, and capacity

for independent thinking.

AI To identify those factors of interest and motivation that facilitates achievement

in any setting where autonomy and independence are positive behaviors.4

Also, a value scale,5 developed by Strodtbeck, was used as a measure of acculturation

to middle class values. This Value Orientation Scale consisted of eight true

and false questions as follows:

-

Planning only makes a person unhappy since your plans hardly ever work

out anyway.

- When a man is born, the success he's going to have is already

in the cards, so he might as well accept it and not fight against

it.

- Nowadays, with world conditions the way they are, the wise person

lives for today and lets tomorrow take care of itself.

- Even when teenagers

get married, their main loyalty still belongs to their fathers and mothers.

-

When the time comes for a boy to take a job, he should stay near his

parents, even if it means giving up a good job opportunity.

- Nothing in

life is worth the sacrifice of moving away from your parents.

- The

best kind of a job to have is one where you are part of an organization,

all working together, even if you don't get individual credit.

- It's silly

for a teenager to put money into a car when money could be used to get

started in business or for an education.

The first three questions have to do with time orientation and mastery over

one's destiny. Questions 4-6 measure familism versus individualism, and loyalty

to extended family versus loyalty to nuclear family. Question 7 tests for group

versus individual orientation. Question 8 deals with immediate versus postponed

gratification.

It was hypothesized that those holding values of the dominant culture would

tend to answer the first seven questions, "false," and the last question, "true," while

those more oriented toward traditional Indian values would tend to answer the

questions in the opposite way. In using the Value Orientation Scale as a measure

of orientation to values of the dominant culture, scores were computed by totaling

the number of "middle class" answers. Thus, a higher score indicated

a greater degree of orientation to middle class values.

Table 32 presents mean scores, by types of school and by sex, for each of the

five scales of the CPI that were used, and for the Value Orientation Scale.

Differences in means were tested for significance by analysis of variance.

Differences

between scores for school types were not significant, either for males or

females, on CAPACITY FOR STATUS, or on ACHIEVEMENT VIA CONFORMANCE. Significant

differences

were found, for both males and females, on SOCIAL PRESENCE and on ACHIEVEMENT

VIA INDEPENDENCE, for females on SELF-ACCEPTANCE, and for females on VALUE

ORIENTATION.

Public off-reservation students scored highest on SOCIAL PRESENCE, while federal

on-reservation students scored lowest.

Public off-reservation and federal on-reservation students scored highest on

ACHIEVEMENT VIA INDEPENDENCE, public on-reservation students ranked next, and

federal off-reservation students ranked lowest.

On SELF-ACCEPTANCE, female students in public off-reservation schools scored

highest, public on-reservation next, then federal off-reservation, and federal

on-reservation lowest. While differences in scores for males were not significant,

it is interesting to note that they follow the same pattern.

Females in public off-reservation schools indicated a higher degree of acculturation

than those in other types of schools by scoring highest on VALUE ORIENTATION,

while those in federal on-reservation schools scored lowest. Differences were

not significant for males.

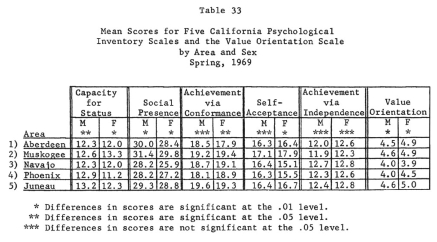

Differences between scores for areas were significant in most instances, as

can be seen in Table 33.

When area scores in Table 33 are examined and compared,

the following facts become apparent:

-

Juneau males and Muskogee females scored higher than their counterparts

from other areas on CAPACITY FOR STATUS.

- Muskogee students, both male

and female, scored substantially higher than students from other areas

on SOCIAL PRESENCE. Next highest were Aberdeen and Juneau, followed by

Phoenix and Navajo.

- Muskogee and Juneau students ranked highest on ACHIEVEMENT

VIA CONFORMANCE.

- Muskogee area female students ranked highest on SELF-ACCEPTANCE,

followed by Juneau, Aberdeen, Phoenix, and Navajo. Muskogee and Juneau

male students also ranked highest, although differences were not significant.

-

Differences in scores for ACHIEVEMENT VIA INDEPENDENCE were not significant,

either for males or females. However, it is interesting that both male and

female students in the Navajo area scored highest on this factor.

- The orders

of rank on VALUE ORIENTATION are very similar for males and females.

Considering the scores of boys and girls together on this measure of acculturation,

Juneau students rank highest, followed by Muskogee, Aberdeen, Phoenix, and

Navajo.

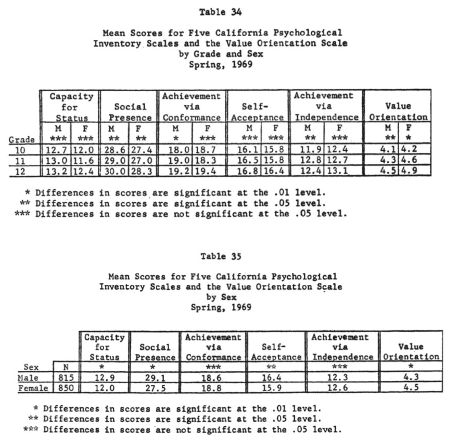

An examination of Table 34 reveals that scores tend to increase for each successive

grade, with twelfth grade students scoring higher than tenth in every instance,

and higher than eleventh with only one exception. Differences in scores between

grades were significant in six of the twelve cases. Attention is directed to

gains on SOCIAL PRESENCE and VALUE ORIENTATION from grade ten to grade twelve.

Apparently the school has a strong socializing and acculturating effect upon

students.

Males scored higher than females on all scales for which differences

in scores were significant, except on VALUE ORIENTATION. The scores indicate

that boys in the sample are more ambitious and self-seeking, feel more self-confident

in social interaction, and have a greater sense of personal worth than girls,

but that girls are more oriented to the values of the dominant culture.

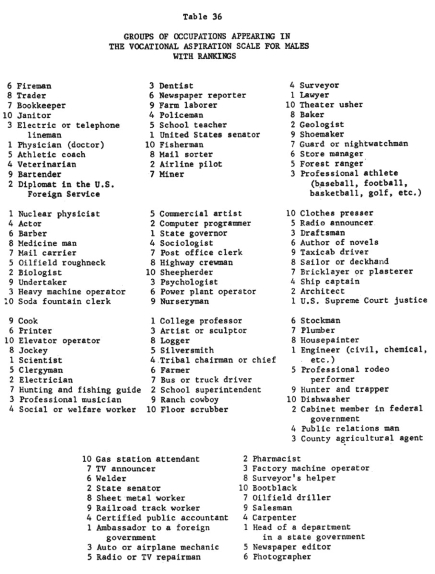

The Vocational Aspiration Scale

A vocational aspiration scale was devised to measure the differential between

level of occupational desire and level of occupational expectation of Indian

high school students. The instrument was administered in the spring of 1970

to 1,286 students in grades eleven and twelve.

In constructing the instrument, 110 occupations were selected for each sex

and listed in order of general standing as determined by reference to rankings

appearing in various studies. Eleven groups of occupations were then formed

from the list, each group containing one occupation from the ten highest occupations

listed, one from the next ten highest on the list, and so on down to one from

the lowest ten on the list. In each of the eleven groups, then, ten occupations

were listed, each one representing a different level of occupational standing

from high to low.

Each group of ten occupations was presented to the examinee at three different

points in the instrument. At one point the examinee was asked to rate the occupations

from one to ten on the basis of general standing, at another point to indicate

which job in the group he would choose to have in the future if free to have

any one he wished, and at still another point to check the job which he feels

is the best one he is really sure that he can get in the future.

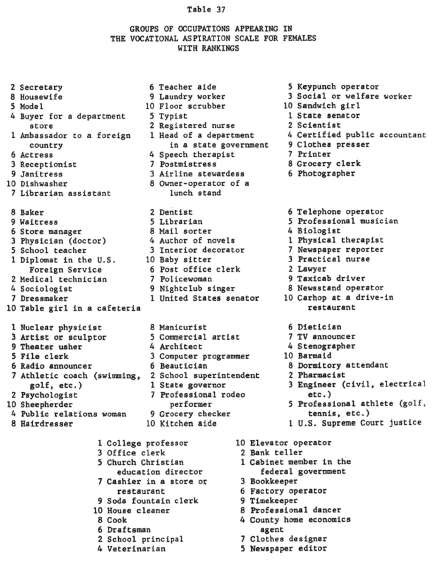

Table 36 presents the eleven occupation groupings appearing in the Vocational

Aspiration Scale for Males and the order of rank in each group as determined

by the mean ratings of the 635 male respondents. Table 37 presents the same

information for the 651 female respondents.

Inspection of Tables 36 and 37 reveals a number of ratings that

would seem to suggest either a lack of information about occupations

or possibly some cultural bias. For example, boys rated computer

programmer higher than sociologist or psychologist, electric

or telephone lineman higher than veterinarian, factory machine

operator and carpenter higher than newspaper editor, auto or

airplane mechanic higher than certified public accountant, heavy

machine operator higher than actor, oilfield roughneck and mail

carrier higher than undertaker, electrician higher than clergyman,

and welder higher than TV announcer. Girls rated medical technician

higher than physician or sociologist, physical therapist higher

than lawyer, practical nurse higher than biologist, file clerk

higher than radio announcer, computer programmer higher than

architect, stenographer higher than dietician or TV announcer,

bank teller higher than newspaper editor, office clerk higher

than veterinarian or draftsman, airline stewardess higher than

speech therapist, and teacher aide higher than postmistress.

In general, the Indian high school students rated the occupations

of lower standing quite accurately but did not display the same

judgment in ranking the occupations considered to be of higher

standing. This may reflect the low socioeconomic backgrounds of

most of the students and their consequent lack of first hand acquaintance

with many of the higher prestige occupations.

In determining the differential between occupational desire and

occupational expectation for each examinee, the difference was

computed between the ranking of the preferred job in each group

and the best expected job in that group, using the examinee's own

job ratings. A total score for each subject was then computed by

subtracting the sum of the desired occupation scores from the sum

of the expected occupation scores. Scores ranged from +84 to -32.

If expectations were lower in rank than preferences, a positive

differential resulted. There were many cases of preference for

jobs having lower standings than the jobs the examinee thought

he could get, resulting in negative scores for about one-third

of the examinees. However the mean differential score for girls

was +7.6 and for boys was +9.4, indicating that, in general, vocational

expectations were somewhat lower than were aspirations, and that

boys, more than girls, felt that they would not be able to procure

jobs of as high ranking as they would like.

REFERENCES

1. Cottle, William C. Examiner's Manual for the School Interest

Inventory. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1966.

2. Owens, Charles S. and Willard P. Bass. The American Indian

High School Dropout in the Southwest. Southwestern Cooperative Educational

Laboratory, Albuquerque, 1969.

3. Selinger, Alphonse D. The American Indian High School Dropout.

Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory, Portland, Oregon, 1968.

4. Gough, Harrison G. California Psychological Inventory Manual.

Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc., Palo Alto, California, 1957.

5. Strodtbeck, Fred L. "Family Integration, Values, and Achievement," in

A. H. Halsey, et. al., Education, Economy, and Society. The Free

Press of Glencoe, Inc., New York, 1961.

VII. RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN VARIABLES

Variables Measured

In order to explore the possible relationships between certain

variables measured by the various instruments administered during

the study, Pearson product moment coefficients of correlation were

computed. The following factors were used.

-

Academic Achievement, as measured by the total battery score

on the California Achievement Test (CAT).

- Mental Ability, as

measured by the California Test of Mental Maturity (CTMM).

-

Value Orientation, as measured by the Value Orientation Scale

(VOS).

- Self-Concept, as measured by the combined scores

of three California Psychological Inventory (CPI) scales--Capacity

for Status, Social Presence, and Self-Acceptance.

- Self-Concept,

as measured by responses on the Semantic Differential (SD)

to the concepts MY SUCCESS IN SCHOOL, MYSELF AS A PERSON,

INDIAN, MY PRESENT LIFE, and MY FUTURE.

- Acculturation, as

measured by 16 questions on the Questionnaire (Q).

- Acculturation,

as measured by 23 selected items from the School Interest

Inventory (SII).

- Achievement Motivation, as measured by the

Achievement Via Conformance (AC) scale of the California

Psychological Inventory (CPI).

- Achievement Motivation, as

measured by the Achievement Via Independence (AI) scale of

the California Psychological Inventory (CPI).

- Vocational

Aspiration-Expectation Differential, as measured by the Vocational

Aspiration Scale (VAS).

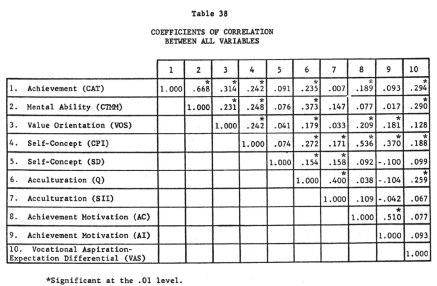

Pearson product moment coefficients of correlation were computed in one operation

between all of the above ten variables in order to provide a matrix as presented

in Table 38. This procedure limited the sample to 391 students for whom there

were data on every variable.

Correlations Between Achievement and Other Variables

As can be seen in Table 38, academic achievement proved to be correlated

significantly in the positive direction with six of the nine other

variables. The coefficient of .667 indicates, as expected, that

there is a strong positive correlation between mental ability and

academic achievement. Probably there are factors other than innate

mental ability that are being measured by the CTMM, such as reading

skill and ability to work quickly and accurately, but, in any event,

it is a strong predictor of academic success.

Of the remaining variables, value orientation has the highest correlation

with achievement, and self-concept, as measured by the CPI, also

appears to have definite relationship to achievement. These two

variables will be discussed at greater length later.

The moderate correlation of .294 between achievement and the vocational

aspiration-expectation differential indicates that there was some

tendency for better students to have greater differences between

occupational desires and actual expectations than did poorer students.

It will be noted that the coefficient of correlation between mental

ability and vocational aspiration-expectation differential is almost

identical to that between achievement and vocational aspiration-expectation.

Possibly the Indian high school juniors and seniors of lower mental

ability and academic standing are cognizant of their limitations

and, therefore, do not aspire as high vocationally as do the more

intelligent students of higher academic rank. Many capable Indian

students, aware of their potential, may desire high ranking occupations,

but, because of problems endemic to their minority group status

and, possibly, because of cultural influences that bear upon them,

they may be doubtful about ever making their aspirations an actuality.

Acculturation (Q) shows some positive correlation with achievement,

indicating a definite but moderate relationship between the two.

Apparently, degree of acculturation, as measured by the sum total

of such characteristics as living off of a reservation, speaking

English in the home, having a TV set, parents having a high school

education, etc., has a positive relation to achievement, but is

not a highly potent factor. The factor of home language was isolated

from other factors included in acculturation (Q) and its relationship

to achievement was investigated. Findings from this analysis are

presented later in this chapter.

Some positive correlation is indicated between mental ability and

value orientation. It would appear that to some degree students

of higher intelligence have internalized more of the values usually

associated with the dominant culture than have students of lower

intelligence.

A moderate and rather substantial positive correlation, as indicated

by the coefficient of .373, exists between mental ability and acculturation

(Q). The explanation may be that students from backgrounds indicative

of greater acculturation simply do better on standardized tests,

like the CTMM, than do students from less acculturated backgrounds

which are generally conceded to produce educational disadvantage.

The coefficient of correlation of .259 between acculturation (Q)

and vocation aspiration-expectation differential is indicative

of a small but significant and definite relationship. It appears

that the more acculturated students had greater differentials between

occupational desires and occupational expectations than did less

acculturated students. Perhaps students with a relatively high

degree of acculturation have had more of the experiences that tend

to raise occupational aspirations but are dubious of their chances

of realizing them, while those of a lesser level of acculturation

tend to expect and be satisfied with lower prestige occupations.

Other correlations showing significant relationships are interesting

but not very enlightening, except perhaps as suggestions for further

steps in analysis. For example, the correlation between acculturation

(Q) and acculturation (SII) is moderately high and might be combined

into one measure for further analyses. Substantial correlations

between achievement motivation (AC) and achievement motivation

(AI), and between self-concept (CPI) and achievement motivation

(AC) were not unexpected. However, the almost zero correlation

between self-concept (CPI) and self-concept (SD) was surprising,

as were the low correlations between value orientation and the

two acculturation variables.

Relationships of Value Orientation and Self-Concept to

Academic Achievement

The relationships between value orientation and academic achievement,

and between self-concept (CPI) and academic achievement were analyzed

further, using a sample of all students for whom data had been

gathered on all three variables. This raised the number of subjects

to 1,664. Pearson product moment coefficients of correlation were

computed, as presented in Table 39.

As can be seen in Table 39 there was a coefficient of correlation

of .359 between academic achievement and value orientation. This

is somewhat higher than the coefficient of .314 appearing in the

matrix constituting Table 78 that was computed on a smaller sample.

The coefficient of .359 indicates a moderately high positive relationship

between degree of orientation to values of the dominant culture

and level of academic achievement.

A significant relationship, but of lesser magnitude, also was evident

between self-concept (CPI) and achievement. The coefficient of

correlation again was higher for the larger sample than that shown

in Table 78. A coefficient of correlation of .264 suggests that

strong positive feelings about self on the part of Indian students

are reflected to a moderate degree in higher levels of achievement.

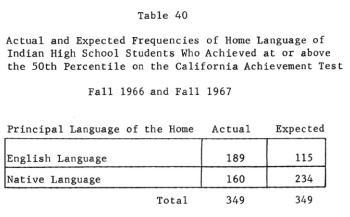

Academic Achievement and the Language of the Home

The relation between principal language of the home and academic

achievement was explored. This was done by comparing home language

of high achievers with home language of the entire sample.

An examination of individual achievement test scores registered

by students in the fall of 1966, and in the fall of 1967 by all

new students added to the sample at that time, revealed that only

349, or less than ten percent, scored at or above the 50th percentile.

It was found that 189, or 54 percent, of these 349 high achievers

came from homes in which English was spoken most of the time, while

160, or 46 percent, came from homes in which a native Indian language

was predominant. For the sample as a whole, 33 percent came from

English speaking homes and 67 percent from native speaking homes.

Thus, if the home language pattern were the same for the high achievers

as for the whole sample, it would be expected that only 33 percent

of the 349 high achievers, or 115 instead of 189, would be from

English speaking homes and 67 percent, or 234 instead of 160, would

be from native speaking homes.

To test for significance in difference of home language between

high achievers and the entire sample chi-square was employed. Actual

and expected frequencies for high achievers are shown in Table

40.

Computation of chi-square yields an X2 value of 63.307. This value

is much greater than the 6.635 necessary for significance at the

.O1 level of confidence, and, in fact, is far beyond the value

of 10.8 necessary for significance at the .001 level. Evidence

clearly indicates that a significantly greater number of students

from English speaking homes and fewer from native speaking homes

were high achievers than the numbers of each in the whole sample

would warrant. Apparently, there is a definite relationship between

the language of the home and academic achievement.

VIII. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Academic Achievement by Types of Schools

The primary concern of the study was to determine whether there

were significant differences in academic achievement between Indian

students in four types of high schools--federal on-reservation,

federal off-reservation, public on-reservation, and public off-reservation.

Using pretest and post-test scores gathered over a span of four

years it was possible to assess achievement for four one-year periods,

three two-year periods, two three-year periods, and one four-year

period. When this was done by grades for each time period, using

the California Achievement Test scores for reading, mathematics,

language, and total battery, 104 categories of assessment resulted.

Controlling for initial individual differences in scholastic aptitude

and academic ability, treatment of the data by analysis of covariance

revealed that differences in achievement between the four school

types, significant at or beyond the .05 level of confidence, had

occurred for only 45 of 104, or less than one-half, of the categories.

Significantly, no reliable differences in achievement between the

four types of schools were found for the four-year period from

the fall of 1966 to the spring of 1970. For the 45 categories for

which significant achievement differences were registered, rankings

were so variable that no hierarchal pattern, or evidence of particular

superiority or inferiority, emerged.

In the light of the above findings it can confidently be concluded

that when initial individual differences in scholastic aptitude