The Indian Child Goes To School

CHAPTER VIII

THE PREDICTIVE TESTING

PROGRAM

PURPOSES OF THE PROGRAM

The general

policy controlling educational loans to Indian students is stated

as follows:

“Loans to Indians for educational purposes may be made

only if no other means of financing them is available. Such loans

may be made

by Indian chartered corporations, unincorporated tribes and

bands, and credit associations. The United States, through

the Bureau of Indian Affairs, also may make loans for educational

purposes,

but only to Indians who are not members of a corporation, tribe,

or band which is conducting credit operations, and who are

not eligible for loans from a credit association, unless an exception

iii a particular case is specifically authorized by the Commissioner.

Indians applying for leans from the United States for educational

purposes must be members of tribes which are being served

by existing Area Offices.”1

The specific reference to the use of tests in the granting of educational

loans to Indians is in the following words:

“Except as provided herein, all applicants for educational

loans are required to take prescribed tests obtainable by authorized

school officials from Haskell Institute, Lawrence, Kansas.

Area

or Agency education specialists will arrange for administering

all tests required. At jurisdictions without such personnel,

the Agency Superintendent may delegate a Reservation Principal,

or Teacher, or other qualified employee to administer the

tests strictly in accordance with the instructions accompanying

test papers. Tests may be waived for students who have a high

school

grade average of B-plus or above, or who have completed a

successful term in college.”

“If, in the opinion of the Area Director of Schools,

the applicable high school testing program meets the standards

of the Bureau testing

program, the Bureau tests may be waived, and the official school

record of all results shall be attached to the application.” 2

As was stated in Chapter II, one of the two principal undertakings

of the education evaluation program was the planning and carrying

out of a testing program which would satisfy the requirements of

the provisions quoted above. There were several additional needs

which would be met by such a testing program. First, other types

of scholarship aid, such as working scholarships, grants in aid,

and tribal scholarships, could he more wisely awarded if such test

information was available. Second, Haskell Institute felt the need

for such test data in granting admission to its Commercial Training

Department. Third, even though the student was not seeking financial

assistance, he and his advisors would often welcome such information

as a help in deciding whether a post-high school course of academic

training should be pursued.

The problem with which responsible officials are faced, whether

they be of the Bureau of Indian Affairs or of the various

tribal groups, is to make in advance an intelligent prediction

as to whether a student is likely to succeed in the course which

he wishes to pursue. Available funds are nearly always limited.

Loans must be repaid. Students who lack the requisite aptitude

for advanced academic study, whether in college, nurses’ training,

or a commercial course, often suffer a loss of time and money as

well as frustration and disappointment.

Prediction of success or failure in academic study at the post-high

school level is at best a difficult business since so many variables

constitute the elements of success. Unquestionably, however,

capacity to learn is one of these elements. An intense desire to

succeed and willingness to work long and hard will go far toward

compensating for low scholastic ability, but these diverse traits

do not always’ exist together in the same person and, in

any case, low scholastic ability remains as a negative factor.

Nor is it simple to determine the academic aptitude of a student

for advanced study. High school marks or “grades” provide

a valuable index for this purpose hut they have a serious limitation.

Most schools grade a pupil largely by comparison with his classmates

and with reference to the general achievement level of the school

of which he is a member. This is good educational practice for

intra-school purposes. However, since school and communities differ

widely in educational attainment, pupil performance earning a mark

of “A” in one school may not merit more than a “C” in

another. Nor are achievement test scores ordinarily obtained

in high school entirely satisfactory for predicting post-high school

success. since they are usually related to the achievement of high

school, not college, students.

PLANNING THE PROGRAM

The Test Battery

With the foregoing considerations in mind the conferees who met

at Haskell Institute in December of 1950 agreed that the consultants

at the University of Kansas would recommend a battery of tests

believed to be valid for the purposes described. The Guidance Bureau

of the University of Kansas would stock and distribute this battery,

would score the tests, and report the results. It was also agreed

that validative studies on the battery would be undertaken. It

was further determined that a fifty-cent fee would be required

of applicants taking the battery, partly to help defray the

cost of processing the battery, and partly as evidence of interest

and good faith on the part of the applicant in requesting the tests.3

Early in 1951 Dr. E. Gordon Collistcr proposed the following battery

of tests to Dr. Willard W. Beatty and Mr. Earl C. Intolubbe and

they approved it. (See Appendix E.) The battery:

Otis Quick-Scoring Test of Mental Ability (gamma)

Cooperative English Test (single booklet edition, lower level)

Cooperative General Achievement Test of Proficiency in Mathematics

Hundred-Problem Arithmetic Test (Schorling, Clark, and Potter)

The Guilford-Zimmerman Temperament Survey

The composition of the battery has not changed since it was first

adopted. All of the tests are of the “paper and pencil” type

and may he administered to groups or to individuals.

The Otis test yields a measure of general intelligence or mental

ability expressed as an intelligence quotient. The Cooperative

English Test is in two parts, English and reading. Each of

these is subdivided: the English into mechanics of expression and

effectiveness of expression, and the reading into vocabulary, speed,

and comprehension sub-scores. Thc Cooperative General Mathematics

Test has two parts, terms and interpretations, and also gives a

total score. The Hundred-Problem Arithmetic Test measures skill

in the four basic arithmetic operations and in fractions, decimals,

and percents. It also yields a total score. The Guilford-Zimmerman

Temperament Survey elicits from the individual, by responses to

a series of questions, a description of his own temperament or

personality.

The same battery was to be given to both college, and commercial

course applicants except for the mathematics test. College candidates

were to be required to take the Cooperative Mathematics Test

because it includes some algebraic and geometric material which

the candidate would quite likely encounter in college. Commercial

course applicants were to be given the Hundred-Problem test since

it was felt that bookkeeping and accounting involve arithmetic

skills almost exclusively.

Disseminating Information to the Field

On February 12, 1951, a letter went out from the Evaluation Office

to all Area Directors of Schools advising them, in brief,

of the main decisions reached at the December conference and promising

that more detailed information on the predictive test battery would

be forthcoming shortly. On February 27 this second communication

went forward to the Area Directors of Schools. Copies of these

letters appear in Appendix E. The several Area Directors of Schools

relayed this information to the various agencies and schools under

their jurisdiction and to public and mission schools enrolling

Indian students. They also devised plans for administering the

tests, taking into account the peculiarities of each area situation.

This phase of the testing program was actually launched when the

University of Kansas began sending out batteries on about March

15, 1951.

Ordering and Administering the Battery

As will be noted in the letter of February 27, a form for use by

the applicant in ordering the battery had been devised and

reproduced in quantity. A supply of these was sent to each Area

Director of Schools and he, in turn, distributed them in his respective

area. The batteries were to be ordered directly from the Guidance

Bureau of the University of Kansas. The Guidance Bureau would then

mail the battery directly to the person named by the applicant,

and approved by a school official, as the one taking the responsibility

for administering the tests. This plan has been followed since.

The application form currently in use appears in Appendix E. A

manual of general and specific instructions for test administration

was prepared by the Evaluation Office and a copy is included with

the test battery when the Guidance Bureau ships the battery. As

has been indicated, the tests are actually administered in the

field by qualified school personnel who are under instructions

to follow the directions faithfully.

Processing the Battery

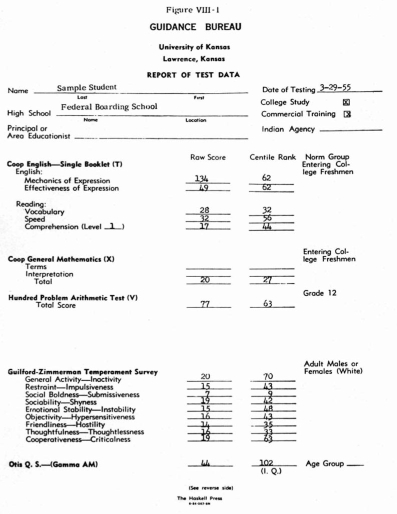

When the applicant has completed the tests, the marked answer sheets

and the other testing materials are returned to the Guidance Bureau.

There the answer sheets are machine scored anti the raw scores

are converted into an l.Q., in the case of the Otis test; and into

centile ranks in the case of the others. The test results are then

recorded on a report sheet designed for the purpose. This report

sheet and the explanation printed on its reverse side are shown

in Figures VIII-l a-id VIII-2 in this chapter. As will he seen

in Figure VIII1, both raw scores and centile ranks are reported,

except that an I.Q. rather than a centile rank is shown in the

case of the Otis test. Six copies of the report are prepared for

each set of scores.

The Number of Students Taking the Battery

As of September 20, 1955, a total of 2,221 Indian students had

applied for and taken the predictive test battery during the five-year

life of the program. This group was almost evenly divided as between

college and commercial applicants, exactly 1,100 being in the former

category and 1,121 in the latter.

Distributing the Reports of Test Data

The Evaluation Office, because of its greater familiarity with

the organizational

structure of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the persons to

whom test results should be sent, until recently has undertaken

the distribution of the reports of test data. This function has

now been assumed by the Guidance Bureau of the University of

Kansas. One copy is retained by the Guidance Bureau and one copy

is sent to the Director of Schools of the applicant’s area.

A third copy is furnished to the applicant’s agency and

a fourth to the high school from which he is being, or has been,

graduated. A fifth copy is placed in a permanent file in the

Evaluation Office. If the applicant is a candidate for commercial

training at Haskell Institute, a copy is supplied to that school.

Figure VIII-2

EXPLANATION

The tests named on the face of this report attempt measurement

in areas which are generally agreed to be important to academic

success, namely; use of language, reading, mathematics, temperament,

and mental ability.

Scores are also reported as centile ranks, in relation to the norm

group on which each test was standardized. For example: If

on applicant has a centile rank of 43 in Mechanics of Expression,

we know that his score on this particular test was equal to or

higher than that of 43% of a large group of entering college

freshmen on whom the test was standardized. On the other hand,

57% of this group had scores higher than the applicant’s.

This affords some knowledge of the applicant’s ability in

comparison with other students of the sort with whom, presumably,

he will soon be competing. All centile ranks are interpreted in

this manner. In the case of the Hundred Problem Arithmetic Test,

the norm group is composed of high school seniors; for the Guilford-Zimmerman

Temperament Survey, white adult males and females from the general

population; and for the Otis Mental Ability Testy the appropriate

age group.

The reading comprehension score is reported for one of three levels.

The level depends upon the number of items the applicant attempted.

Level I may be regarded as the slow reading group, Level II as

the average reading group, and Level Ill as the fast reading group.

Centile rank of the applicant in reading comprehension, then,

is based on scores of those students who read at approximately

the same rate he does.

In the case of the Guilford-Zimmermon Temperament Survey, scores

and centile ranks are reported on each of nine different traits.

The higher the centile rank, the greater is the applicant’s

tendency to evaluate himself toward the upper or left hand side

of the scale, as described on the face of this report. The Guilford-Zimmermon

m6nual says. “In most cases the optimal scores do not extend

to the top of the scale, but at some moderate position between

the mean and the top.”

Generally, however, one can predict with more confidence from extremely

high or extremely low scores than from those which lie closer to

the average of the group.

It is hoped that persons making decisions or recommendations affecting

the granting of educational loans, admission to certain courses

of study, etc., will consider data contained in this report as

only a part, but an important and useful part, of the total information

about the applicant which should be considered. School marks; study

and work habits, ability to adjust socially, financial resources,

and the attitude of the applicant and his family toward past high

school education are, of course, some of the other considerations

which must be taken into account.

INTERPRETING THE TEST RESULTS

The reader’s attention is again invited to Figure VIII-l.

The report sheet bears a set of scores actually obtained by a twelfth-grade

student in one of the Federal hoarding schools. They are not necessarily

typical of the scores of other students, but they will serve well

for purposes of illustration, particularly because this applicant

took 1)0th mathematics tests.

The raw scores are important only to Haskell Institute which uses

these in preparing a profile for each of its candidates as will

be explained later in this chapter. The centile rank column provides

the information which is useful in making decisions concerning

college or nursing aspirants. The particular norm group, shown

at the right hand side of the sheet, must he borne ii-. mind however.

The norm groups for the Cooperative English and Cooperative Mathematics

tests are composed of large numbers of entering college freshmen.

Specifically, these college freshmen were enrolled in small

colleges and teachers’ colleges as distinguished from two

other Cooperative norm groups: large private universities and those

of the state university class. It had been observed that the majority

of Indian students attend the smaller schools. The norm group for

the Hundred-Problem Arithmetic Test is made up of twelfth-grade

students and for The Guilford-Zimmerman Temperament Survey

of adult white males and females from the general population.

The l.Q. is derived by comparison with an appropriate age group

from the general population.

An official charged with making a decision or recommendation in

the case of the applicant shown in Figure VIII-l would first read

the explanation printed on the back of the report sheet and shown

in Figure VIII-2. He would then be in a position to make certain

judgments about this applicant’s scores. He would observe

that for the most part the applicant is not very far from

the average of the norm group. On both of the English skills he

is at the sixty-second percentile which means that his scores are

equal to or better than sixty-two percent of entering college freshmen.

Thirty-eight percent have scores better than his. Since nearly

all regularly enrolled college students must take courses in rhetoric

and composition. it is important to know haw this student compares

in English skills with others of the sort with whom, presumably,

he will soon be competing. Apparently our student in Figure VIII-I

compares quite favorably. Proficiency in reading is important to

success in college, for college students are required to do a great

volume of reading and to understand what they read. Our applicant

in Figure VIII-l does not stand quite so favorably in his reading

skills. He is at Level 1 which indicates that he did not attempt

a large number of items. His percentile scores of fifty-six in

speed and forty-four in comprehension indicate. however, that he

is close to the average for those students who read at about his

rate. He is lowest in vocabulary in which sixty-eight percent of

entering college freshmen excel him.

He is higher than only about one-fourth of entering college freshmen

in general mathematics, hut excels nearly two-thirds of high school

seniors in arithmetic skills. This is explainable on the basis

that his high school may not have offered, or he may not have taken,

advanced courses in algebra or geometry. It does not remove the

probability, however, that he will have some difficulty with

college algebra or trigonometry.

On the temperament survey his responses indicate he lacks social

boldness hut is above average in general activity and cooperativeness.

He feels that he is somewhat below average in friendliness and

thoughtfulness, but about average on the other traits.

His obtained I.Q. was 102 which is about average for the general

population hut probably somewhat lower than the average for entering

college freshmen who are, by one means or another, a selected group.

The official might reasonably conclude that the picture is, on

the whole, not a bad one so far as academic aptitude is concerned

and that the applicant merits consideration for some financial

assistance in trying for college education. The scores certainly

do not guarantee his success, but it appears that if other

factors arc favorable this applicant might well succeed in college.

Two points need to be emphasized here. First, comparing the applicant

with a group of entering college freshmen is quite different from

comparing him with his high school classmates who live in the same

community with him. Second, as is stressed in the last paragraph

of the explanation in Figure VIII-2, the test scores are only one

useful part of the total information about the applicant which

is needed to make an intelligent decision.

Both the University of Kansas and the Evaluation Office of the

Bureau have always abstained from making recommendations in individual

cases concerning the granting or denying of loans or admission

to certain courses of study. They have believed their responsibility

to be the furnishing of objective test data, in meaningful form,

to the persons charged with the responsibility for making such

decisions, and, whenever possible, to instruct these persons in

the techniques of interpreting such data.

VALIDATION OF THE PREDICTIVE BATTERY

There has been no opportunity up to this time to conduct any follow-up

study of college loan applicants. Thus, there is no objective

information available which could be used to determine the usefulness

of the test battery in predicting what may be very generally called “success

in college.” A discussion of the ability of the test battery

for predictive purposes must be restricted to the work which

has been done with applicants to, and students of, the Haskell

Commercial Department.4

Selection of a Criterion

In order to predict “success in training” there must

be some measure of success, cornrn)nly called a criterion.

A number of criteria were suggested:

I. Passing a civil service examination in the field of training.

2. Obtaining a position which could not have been obtained without

training.

3. Making average or better grades while in training.

4. Completing training.

School personnel at Haskell Institute desired to make use of the

test battery as early as possible, i.e., for aid in the selection

of commercial students for the school year 1951-52. Consequently,

there was little time available to make an exhaustive follow-up

study of commercial graduates. Such information could have

made the use of the first two criteria possible, but it was not

possible to obtain it in such a short time. The third criterion

of teachers’ grades was recognized as being traditionally

unreliable and so its use as a single criterion was not made.

The criterion of completion of training was used, but in a modified

form as will be explained below.

Early in the spring semester of 1951 the test battery was administered

to students in both years of the commercial course. The training

program was viewed as a selective process in which the poorer students

in this field were gradually weeded out. Thus one might expect

that senior students would score higher than junior students on

most of the tests, especially since they had the advantage

of an extra year of training. Such was not the case. however. The

average score of the forty-four seniors did not differ except within

the limits of chance variation from the average score of the sixty-six

juniors, with but two exceptions: mechanics of English and the

subtraction subtest of the arithmetic test. The seniors scored

higher, on the average, on both of these. Commercial department

teachers agreed that practically all students who successfully

completed the first year of training likewise successfully

completed the second year if they returned to take it. Also, most

of the students who would fail in the training program would have

been dropped by the second semester of the junior year when the

tests were administered. Thus it was felt that for the purpose

of a convenient criterion with this battery of tests successful

completion of the first year of training could be considered equivalent

to successful completion of both years.5 This was not intended

to imply that the senior year in the department provided no increment

in learning for the commercial students. But since the tests in

the battery were not designed to measure the specific objectives

of the Haskell commercial program, they might not reflect any real

differences which could develop in commercial skills between the

seniors and juniors as a result of training.

Validative Studies

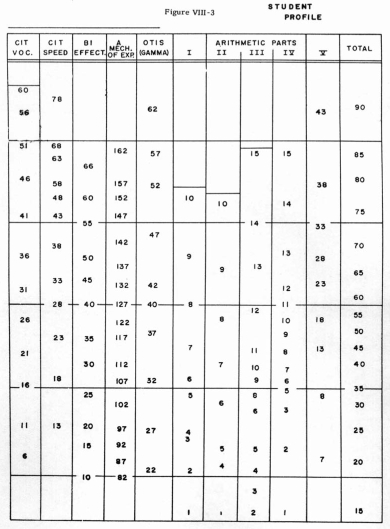

The Original Student Profile. Investigation up to this point left

unanswered questions with regard to how the successful commercial

students differed from unsuccessful ones on their test scores.

In the meantime the battery was being administered to applicants

for admission to the Haskell Commercial Department. A temporary

individual profile sheet, shown as Figure VIII-3, was prepared,

using the score distributions for sixty-seven first-year students.

This profile sheet showed the raw score equivalents for the average

score and plus-and-minus one and two standard deviations from the

mean for the group on each test. The mean line and plus-and-minus

one standard deviation lines for the eighteen lowest achieving

students in the group were drawn on a sheet of transparent acetate

material. The acetate sheet was then superimposed on the profile

and a graphic picture was provided of a candidate’s

performance in relation to the mean of the lowest group of eighteen

students in the first year of the commercial course. Very loosely

this mean line was used as a “cut off line” below which

the prognosis for success of the applicant was not considered good.

No harsh or arbitrary decisions were made on the basis of this

alone. All other information about a candidate was utilized including,

of course, his high school transcript. The technique, which has

been described, was utilized simply as a guidance tool. Some students

whose scores were below the line, were accepted on the basis of

ameliorating information. The commercial staff reported a rather

marked decline the following year both in the number of drop outs

and in the incidence of maladjusted pupils.

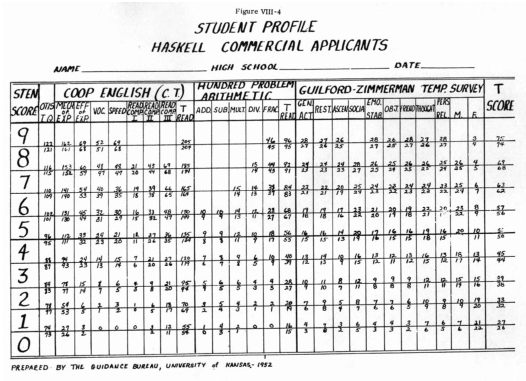

The Ferguson Study. An intensive validation study was conducted

by William A. Ferguson in 1952.6 He analyzed the test scores of

applicants to the commercial program for the fall of 1951. He then

compared the results of those who were accepted for that school

year with the results of those who completed the academic year.

There were 187 who took the test battery, of whom 101 were accepted

for admission (although not all of these matriculated), and

fifty-four successfully completed the first year of training.

As a basis for comparison, the frequency distributions for the

tests of all 187 applicants were used. Centile rank equivalents

for each raw score were obtained and raw scores were converted

into normalized standard scores having a mean of 50 and a standard

deviation of 10.

Thus, since the same individuals were administered the entire battery,

the scores on all tests were rendered comparable. To further simplify

the handling of data on IBM processing machines, and as an aid

in classifying students, a sten scale (standard scale of ten units)

was devised for the normalized distributions. The sten scale ranges

from a low score of 0 to a high score of 9. It has an average score

of 4.5 and a standard deviation of 1.6667 sten score units.7 The

upper and lower raw score limits for each sten score on each test

were found and this information was used in constructing a new

individual profile sheet. This profile sheet is shown as Figure

VIII-4. It was used at Haskell Institute as an aid in selection

for the next two years.

Ferguson compared the average score on each test of 142 applicants

with the average score of forty-five who took the tests but did

not apply for admission. He found statistically significant differences

in favor of the applicants on every test except the Otis Test of

Mental Ability where no difference was obtained. The same procedure

was used to test the differences between the average scores

for the applicants and the average scores for those who successfully

completed the first year of training. For the most part the means

between these two groups were not significantly different. The

average scores on the aptitude and achievement tests were

without exception slightly higher for the successful group than

they were for the accepted group, however. Ferguson concluded that

the lack of differences between the scores of accepted and successful

students indicated that students dropped out of training for

reasons not measured by the battery. But he did develop transparent

acetate overlay sheets eor each of the above two groups, showing

the mean and plus-and-minus one standard deviation from the

mean, so that an individual’s profile could he compared to

them.

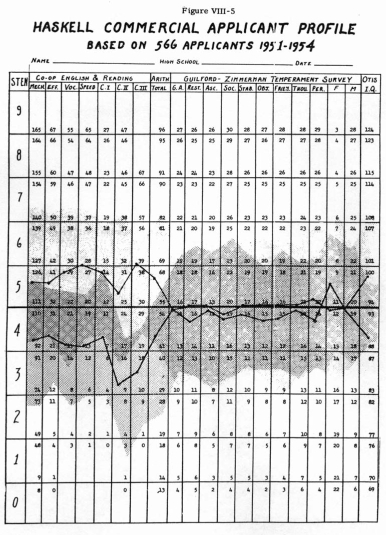

Construction of Current Norms. In the spring of 1954 Ralph E. Kron

gathered together all of the test results of Haskell commercial

applicants from the beginning of the program through, March

31, 1954. There were test scores for 566 applicants (408 females

and 158 males) for the battery over the three-year period. The

same procedure that Ferguson used was applied to these data. Raw

score frequency distributions were made, centile ranks were derived,

and a conversion to normalized T-scores was made for each distribution.

The limits of sten scores were then obtained. Inrercorrelations

of the test scores of the 408 females in this population are

shown in Appendix E. Two samples, one of one hundred females

and the other of one hundred males, were drawn at random for a

study of the reliability of these tests for this population.

Appendix E shows the standard error of measurement and the reliability

coefficient for each sex on each test of the battery.

A new individual profile sheet, shown as Figure VllI-5, was constructed,

based or the larger population of applicants for the battery. The

only major format change from Ferguson’s profile sheet was

that only the total arithmetic score was scaled, rather than including

all of the arithmetic subtests in addition to the total score.

An important addition to the usefulness of the profile sheet for

interpretation purposes was made. This was the printing on the

profile sheets of the average profile made by a “pass” group

of 218 students who had completed at least one year of training,

as well as the average profile for a “tail’’ group

of forty-five students. The range of scores between plus-an(1—u1~1nus

one standard deviation from the mean score was shaded in blue

for the pass group and in red for the tail group.

An interesting phenomenon was noted when pass and fail group raw

score points on the tests, for the mean and plus—and-minus

one standard deviation (SI).) from the mean were compared. For

all the tests except The Guilford-Zimmerman scales, the average

score for the pass group approximated the value for plus I S.D.

or the ail group while minus 1 status for the pass group approximated

the average score or the tail group. The profile sheet then appeared

to be fairly neatly divided into fuse levels:

- Scores greater than plus I S.D. of the pass group;

- Scores

greater than the mean of the pass group or plus I S.D. of

the fail group, but less than plus 1 S.D. of the pass group.

- Scores greater than minus 1 S.D. of the pass group or the

mean of the fail group, but less than the mean of the pass

group

or plus 1 S.D. of the fail

group.

- Scores greater than minus 1 S.D. of the fail group but

less than the mean of the fail group or minus 1 S.D. of the

pass group.

- Scores less than minus 1 S:D: of the fail group.

Raw score limits for these five levels were set up. Expectancy tables for passing

and failing were then constructed hi, calculating the percent of those scoring

at each level who either passed or failed. Such tables can be of great use

as an aid in the selection of students who stand the greatest chance for success

in the program. (See Appendix E.)

Several attempts have been made to assign weights to various of thc test scores

in order to increase their ability to discriminate between various criterion

groups. To date none of the weighting procedures has been successful but work

is continuing along this line of research.

Investigation of Personality Traits. A few studies have been made in the Haskell

Institute Commercial Department of the personality factors involved in

success in training there. There were a few differences in temperament traits

between the junior and senior women in the spring of 1951, as measured by The

Guilford-Zimmerman Temperament Survey (GZTS). The junior women scored significantly

higher on the average in the traits of emotional stability, general activity,

and friendliness, and they approached a significantly higher average score

in sociability. Mrs. Louise L. Baker, who was head of the Haskell Institute

Commercial Department for nineteen years, was greatly interested in this phase

of the testing program.8 She found that the median scores on the GZTS of eleven

drop-outs from the 1950-51 program were considerably more in the direction

of hyper-sensitiveness and intolerance than the average scores of students

in the 1951-52 program. The same conclusions were true for fourteen drop-outs

in 1951-52. In addition they seemed to be more submissive, shy, and belligerent.

The twenty-two drop outs for 1952-53 were more impulsive, emotionally unstable,

hypersensitive, and intolerant. Mrs. Baker compared the median scores of eighteen

drop outs and students receiving failing grades with the median scores of the

twenty students who received the earliest job appointments of the 1952 graduating

class. The drop outs were found to be considerably more belligerent, intolerant,

and impulsive than those who received early job appointments. Further study

is now under way in this area in an effort to throw more light on the motivational

factors involved in the drop out problem of students who appear to be qualified

for success in the-program but who do not remain to complete all of the work.

1 Indian Affairs Manual, Vol. IV, Part VII, Chap. 12,

Sec. 1201.

2 Op.Cit. Vol. IV, Part VII, Chap. 12, Sec. 1202.05.

3 In a letter dated February 16, 1953, the Evaluation

Office notified school administrators that the fifty-cent fee would no longer

be

required of applicants for the battery of tests. General dissatisfaction

with the fee requirement had been expressed by school officials. Collecting

the money and transmitting it added to the administrative burden of giving

the tests and slowed down the testing procedure. Early in 1953, upon the

recommendation of the Evaluation Office, the Central Office authorized removal

of the fee requirement.

4 The use of the predictive battery as an aid in selection

before it has been thoroughly validated was clearly seen as a complicating

factor in the validation procedure.

5 E. Gordon Collister, Kenneth E. Anderson and Donald

K. Ottman. “Prediction of Success in the Commercial Program at Haskell

Institute.” Unpublished report, Kansas University, 1951.

6 William A.

Ferguson. “An Analysis of the Test Scores of Applicants to the

Commercial Program at Haskell Institute,” Unpublished master’s

thesis, University of Kansas, 1952.

7 This method of obtaining derived scores was suggested

by Donald K. Ottman. It is a slight revision of the Canfield sten score scale.

Cf. Canfield, A. A. “The ‘Sten’ Scale – A Modified

C Scale,” Educational and Psychological Measurements, XI (1951), Summer,

295-297.

8 Louise L. Baker. “The Testing Program for Selection

of Haskell Commercial Enrollment,” Unpublished report, Haskell Institute

Commercial Department, 1953.

|