The Indian Child Goes To School

CHAPTER IV

A

COMPARISON OF THE ACHIEVEMENT OF PUPILS BY RACE-SCHOOL GROUPS

WHAT

IS BEING COMPARED?

It is natural and inevitable, we suppose, that

people generally should be interested in comparing school children

of different

races with each other. Certainly any teacher who has worked very

long with Indian children is accustomed to being asked by interested

or merely curious laymen to make such comparisons. Most often the

teacher is asked whether the Indian pupil is as intelligent as

his white classmate. This is indeed a difficult question to answer,

for the inquirer usually has no intention of sitting patiently

while the teacher explains that anthropologists and ethnologists

are pretty well agreed that race alone is not a determining factor

in intelligence and that no one race has a monopoly on all the

brains in the world. The questioner becomes increasingly restless

as the teacher goes on to say that we have no really suitable tests

for measuring the intelligence of Indian pupils since the ones

available are based largely on English verbalism and are loaded

with questions pertaining to the dominant culture of the country.

The chances are good that all the questioner really wanted to know

was whether Indian children do "as well" in school as

non-Indian children. Many laymen tend to equate school success

with intelligence; that is, they assume that intelligence is the

sole factor which influences learning. This is far from true. Some

of tile other factors which are believed to influence learning

will be discussed in Chapter VI. .

In any case no intelligence test data were obtained in the present

study. The tests used were achievement tests. Achievement tests

seek to measure how much or how well a child has learned. Intelligence

tests attempt to discover his mental capacity for learning.

Why Intelligence Tests Were Not Given

Some readers may feel that, inasmuch as intelligence is admittedly

an important factor in the learning process, not attempting to

measure it was a serious omission. The plain fact is that, in the

opinion of the investigators, a valid measurement of the intelligence

of pupils was not possible in the present study. First of all,

it would have been necessary to use a group test which could have

been scored by machine. Furthermore it would have hall to be usable

for children from arc nine years to adulthood. Nearly all group

intelligence tests are highly verbal. Those which claim to be non-verbal

in content must rely on verbalism in the giving of directions.

Nearly all intelligence tests, individual as well as those of the

group type, contain items drawn from the major culture of the country.

This, it was felt, would operate against the underacculturated

groups in the study, both Indian anti white. No instrument was

found which satisfied all of the requirements and contained none

of the disadvantages mentioned above.

Differences in the Measuring of Intelligence and Achievement

We accept the concept of innate mental capacity, which differs

qualitatively and quantitatively from individual to individual,

as a valid one. It would he very helpful in educational situations

if we could measure it as such. In truth, however, we have never

been able to do this. From the moment of birth environmental influences

begin to act upon the individual. These do not change his innate

capacity but they prevent the accurate measurement of it. The same

language handicaps or other cultural disadvantages which adversely

affect the educational achievement of a child would tend to influence

his intelligence test scores. Achievement tests on the other hand

are designed to cover material which presumably has been “taught” in

school. By use of them we simply seek to discover how much the

child has learned. They are not invalidated merely because the

learner faces learning disadvantages, so long as the content is

consistent with the courses of study and the learning goals of

the school which the child attends. No such validity can be claimed

for a verbalized, culture laden, group test which purports to measure

the innate mental capacity of an under-acculturated child.

THE COMPOSITION OF THE RACE-SCHOOL GROUPS

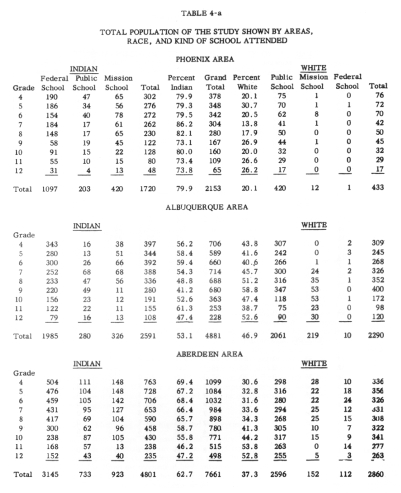

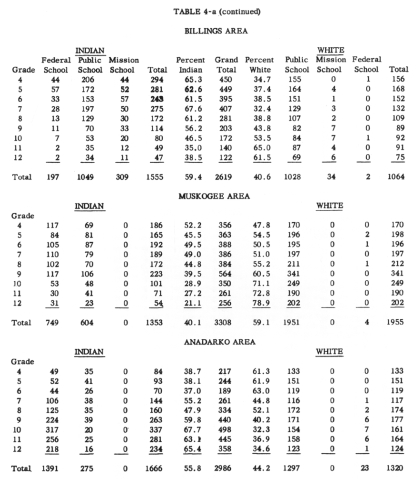

As was described in Chapter 11, the population of Indian children

in the present study was composed of pupils in three different

types of schools: Federal, public, and mission. Through the generous

and excellent help of many public and mission school administrators

and teachers, rather large numbers of Indian pupils were tested

in both public and mission schools, as well as a large number of

white children in public schools. Table 4-a shows the composition

of the entire population tested by areas, grades, and race-school

groups.

Does Type of School Administration Affect Achievement?

Again it is inevitable that there should be interest in the relative

levels of achievement of Indian pupils in the three types of schools.

There is a rather popular supposition that these school types differ

from each other quite radically in point of curriculum, qualifications

of teachers, teaching methods and materials, and educational goals,

simply because they operate under separate administrative authorities.

These differences are more often imaginary than real as anyone

who takes the trouble to investigate will discover. This is particularly

true for the elementary grades and for the basic skills which were

measured in this study. It would be more logical and accurate to

assume, unless there is strong evidence to the contrary, that all

three types of schools draw upon the common pool of educational “know

how” which has been developed in American schools.

()f course, it is necessary for the school, of whichever administrative

type it may be, to modify its instructional program to meet the

needs of those pupils who enter school unable to speak any English

or who speak it poorly. Federal schools in the Phoenix, Albuquerque,

Billings, and Muskogee Area have a high percentage of such beginning

pupils as do mission schools in the Phoenix and Albuquerque Areas.

Public schools have faced this problem less frequently than have

the Federal and mission schools. It is mandatory that instructional

procedures, techniques, and materials be adapted to the needs of

the non-English-speaking beginner.

THE ORDER OF ACHIEVEMENT OF RACE-SCHOOL GROUPS

Nevertheless, and in spite of what has been pointed out in the

section lust preceding. the four race-school groups do arrange

themselves .into a fairly definite hierarchy or order of achievement

as follows:

1. White children in public schools

2. Indian children in public schools

3. Indian children in Federal schools

4. Indian children in mission schools

Method of Establishing the Hierarchy

Table 4-b shows the hierarchy for each of the areas separately.

These were determined by exactly the same method employed in Chapter

III in determining the hierarchy

of achievement for the six areas. Here a comparison was made of the mean raw

scores of the race-school groups for each of the six skills, and total score,

for each of the nine grades in each area. One minor exception to this occurred

in the Billings Area where there were no Federal school pupils

in grades eleven and twelve, and so they could

he compared with the other race-school groups only through grade

ten. Normalized standard scores were assigned to the ranks of

the means for race-school groups in each grade. These scores

were then averaged for each group. Except where noted in Table

4-b, differences between the means of standardized scores assigned

to race-school groups were statistically significant.1

Two Exceptions to the General Hierarchy

An inspection of Table 4-b will reveal that the Phoenix and Billings

Areas conform exactly to the general hierarchy outlined above.

So do the Anadarko and Muskogee Areas, except that there were no

mission school pupils tested in those areas.

In the Aberdeen and Albuquerque Areas, however, exceptions to the

general hierarchy of achievement do occur. In the Aberdeen Area

the over-all achievement of Indian pupils in mission schools did

not differ significantly from that of Indian pupils in public schools.

Both groups were significantly lower than white pupils in public

schools and significantly-higher than Indian pupils in Federal

schools. In the Albuquerque Area, again there was no significant

difference in the over-all achievement of the Indian groups in

mission and public schools, but the Indian pupils in Federal schools

were significantly higher than both. They, in turn, were significantly

lower than the white pupils in public schools. Data shown and-discussed

later in Chapter VI will suggest partial explanations for these

departures from the general hierarchy.

Tables of raw score means and tables of differences in means among

the race-school groups are shown in Appendix C. These are shown

by areas, by grades, and by skills. A careful examination of these

tables by the reader will disclose that they support the hierarchies

as shown in Table 4-b. Raw score mean differences which are statistically

significant are so indicated.

SHOWING DIFFERENCES BY SKILLS AND BY GRADES

It must be remembered that the hierarchy of achievement referred

to above rests upon comparisons of the race-school groups on seven

different skills in nine different grades; sixty-three in all for

each area. The hierarchy of achievement, then, is a general one

and simply reflects the rank ordering of race-school groups which

was most typical of these comparisons. In many of the sixty-three

comparisons in each area, the order of achievement was different

from the general hierarchy.

Average, and Below and Above Average Pupils, Shown by Percentages

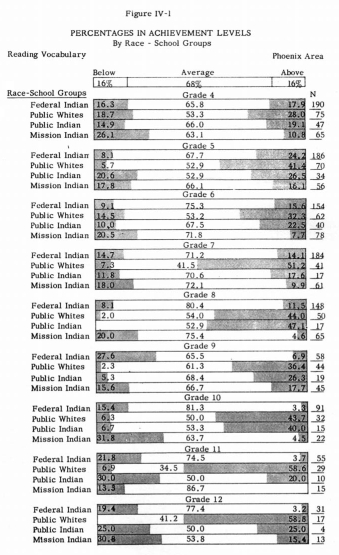

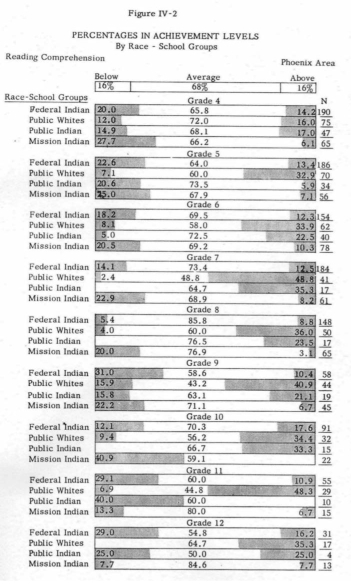

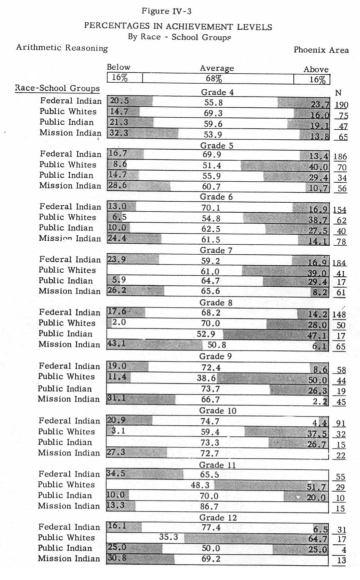

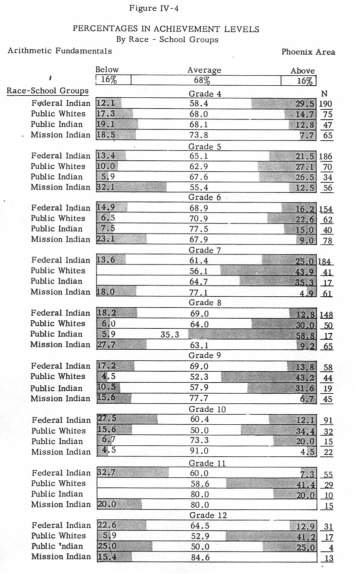

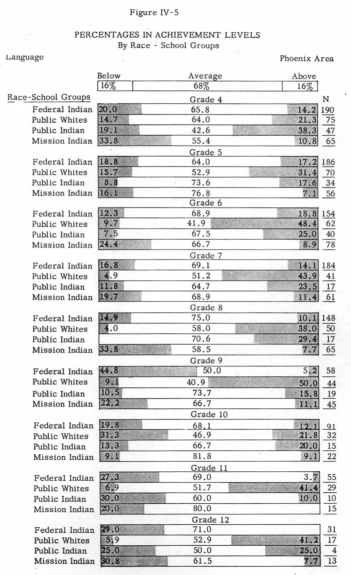

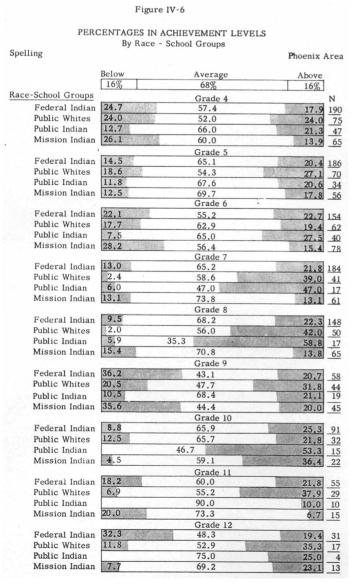

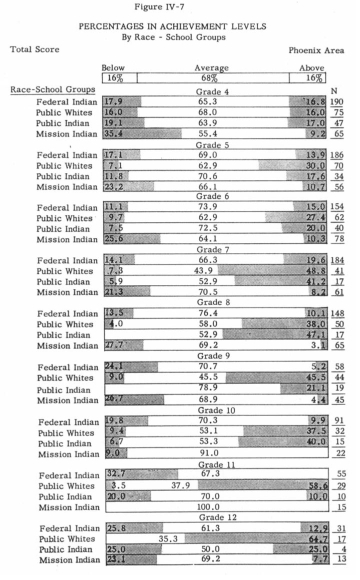

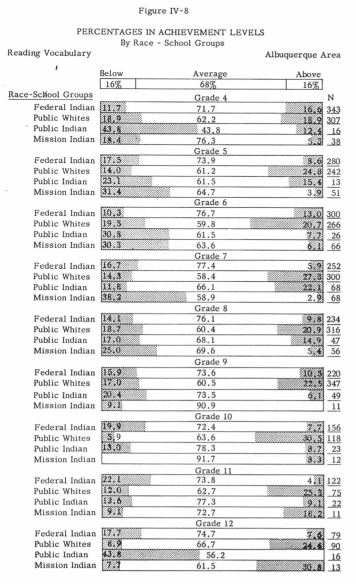

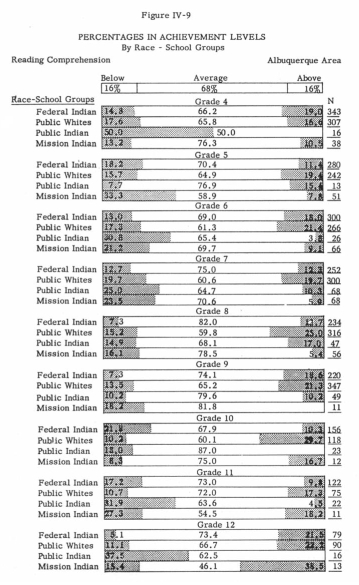

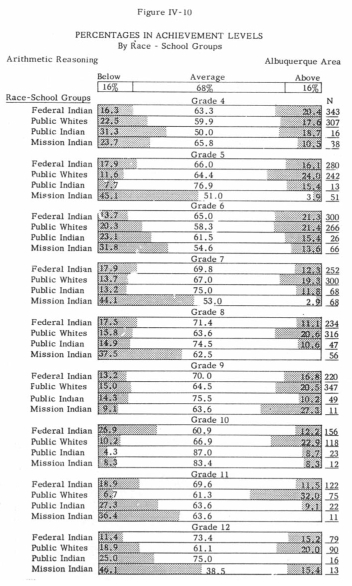

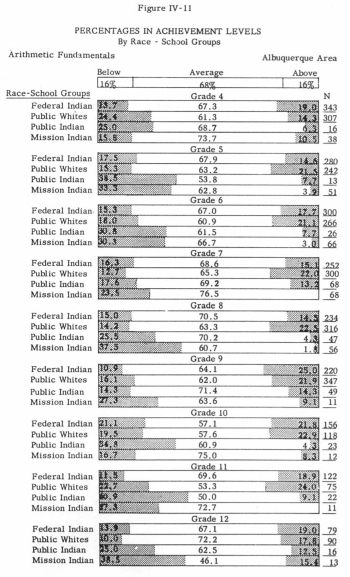

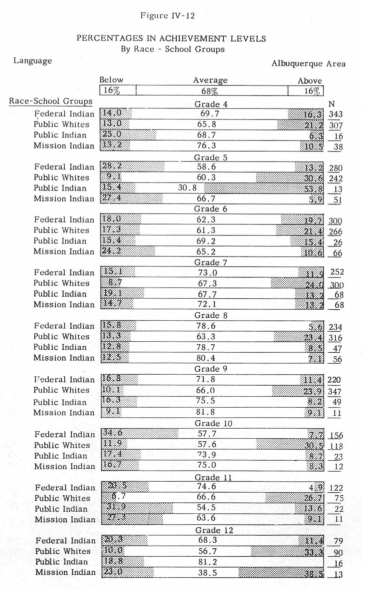

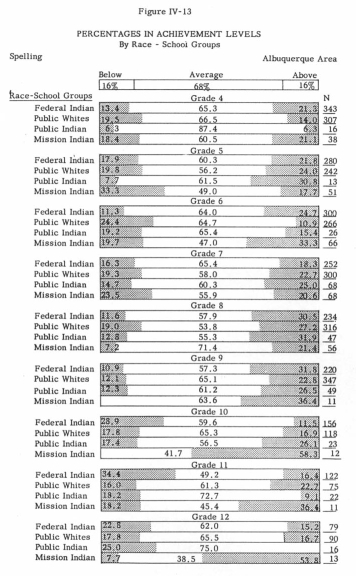

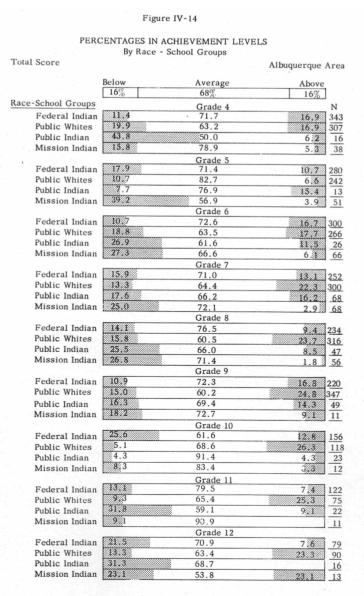

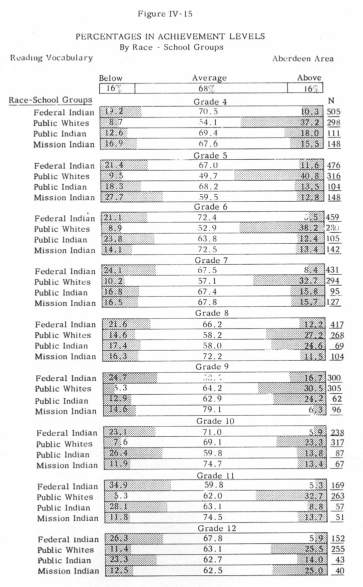

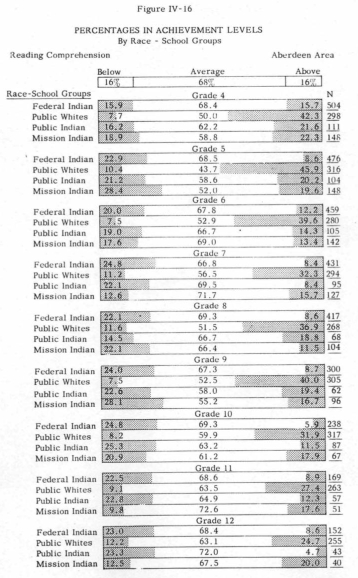

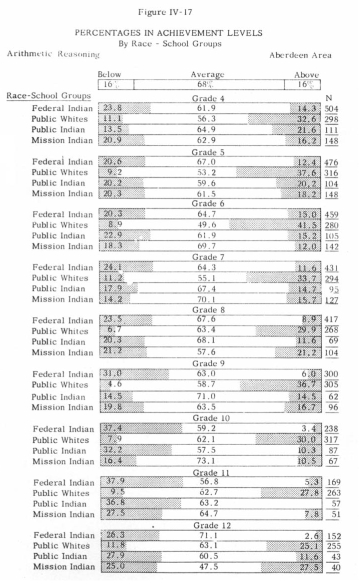

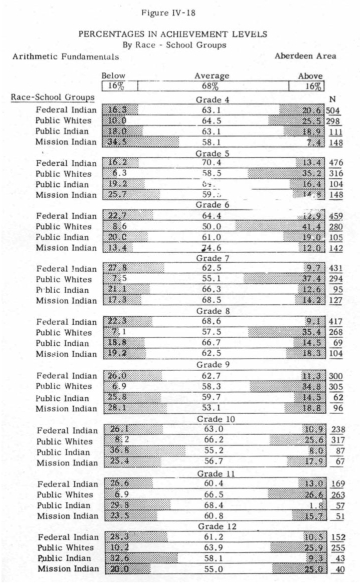

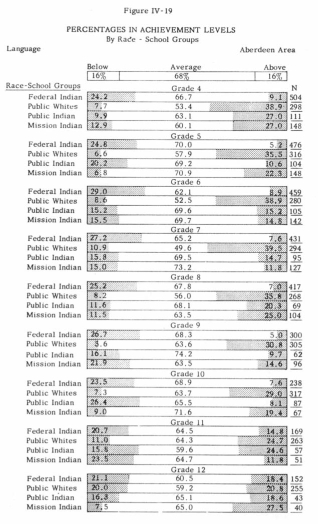

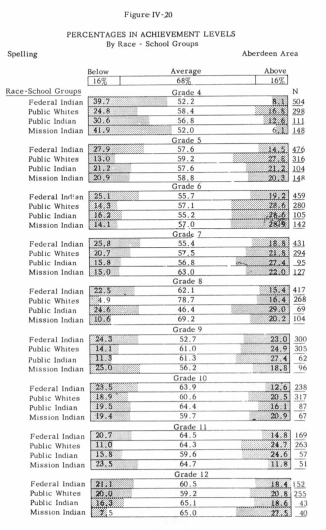

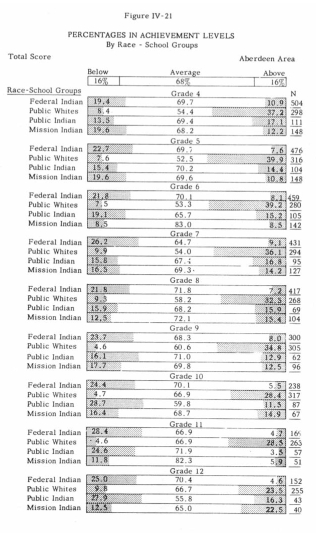

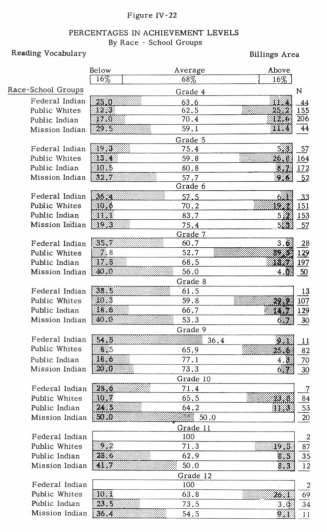

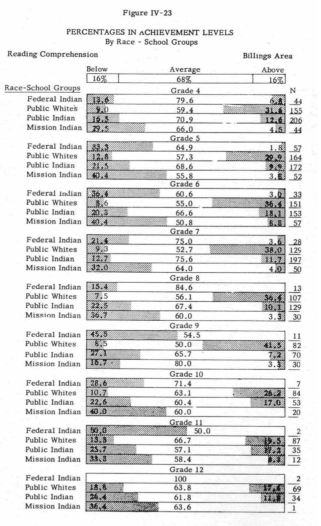

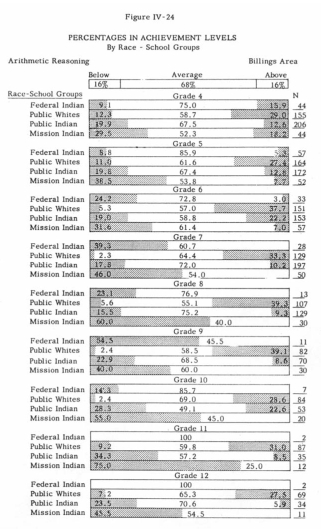

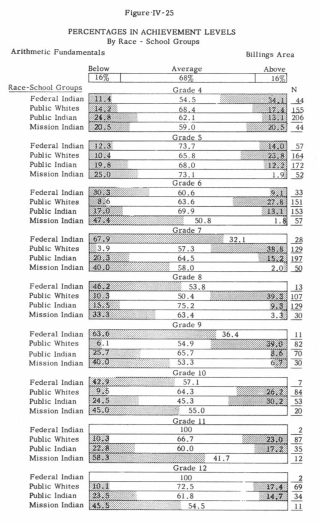

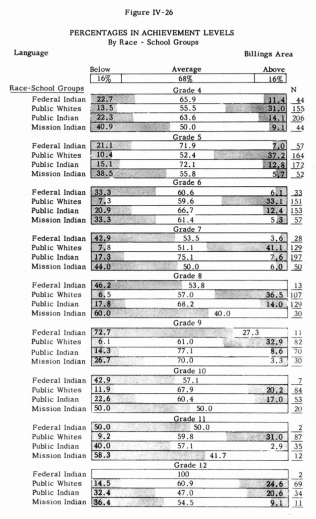

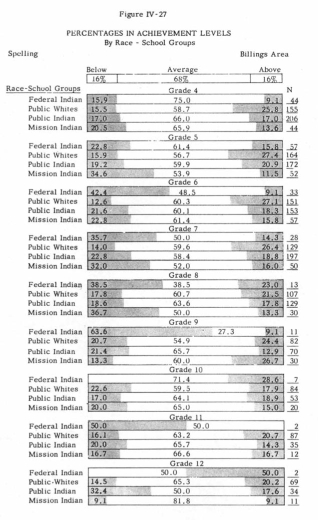

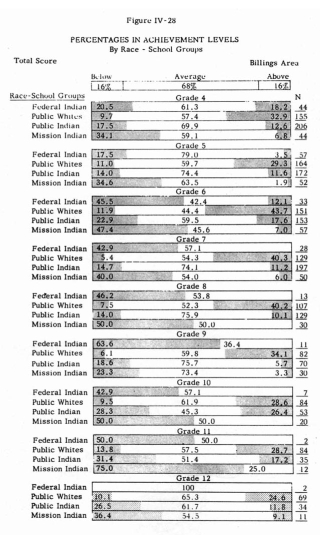

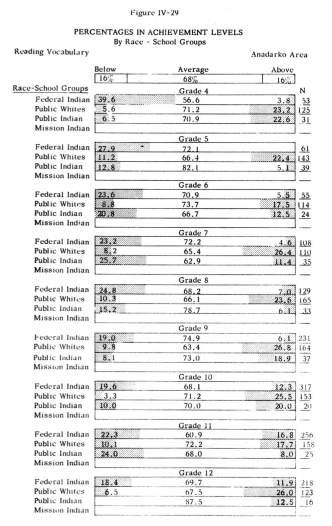

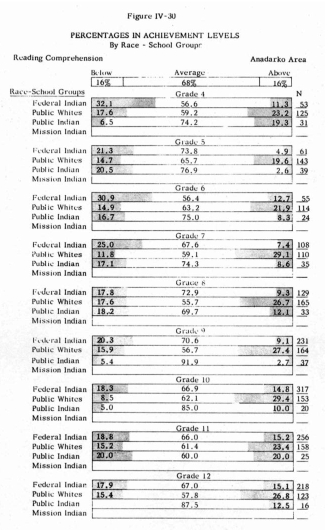

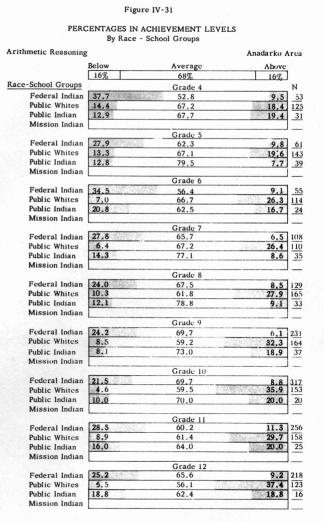

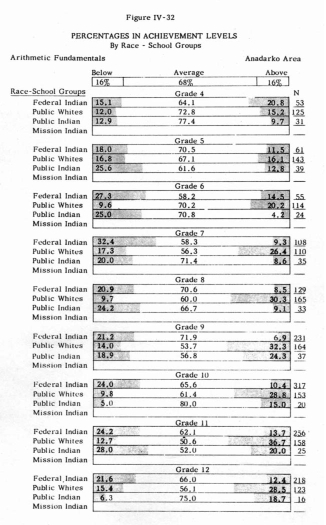

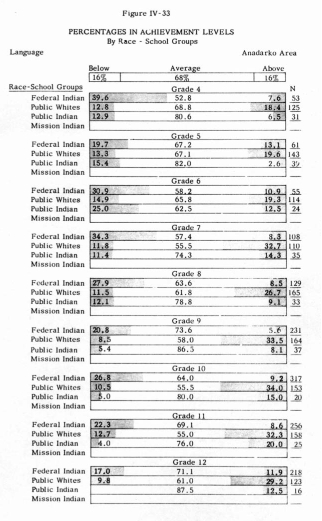

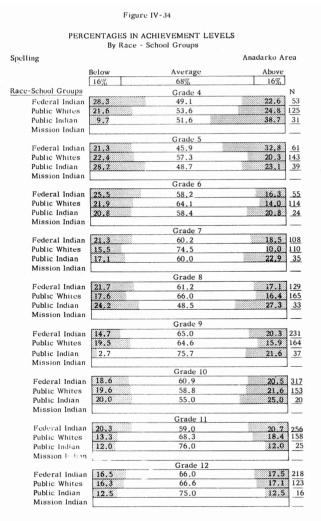

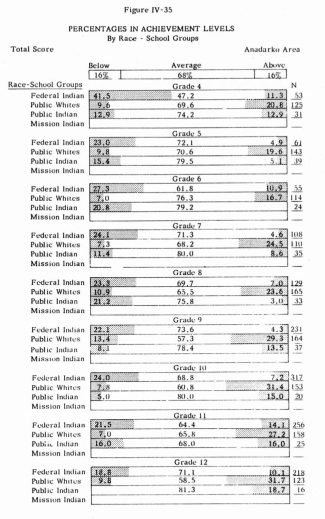

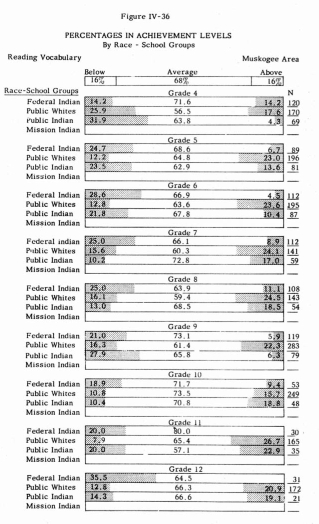

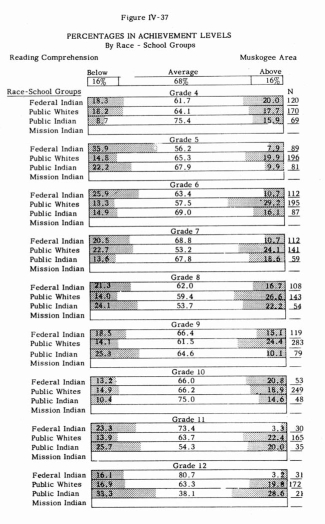

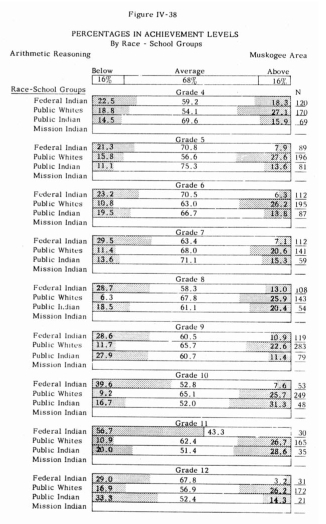

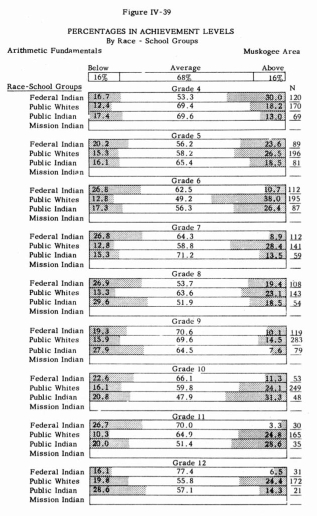

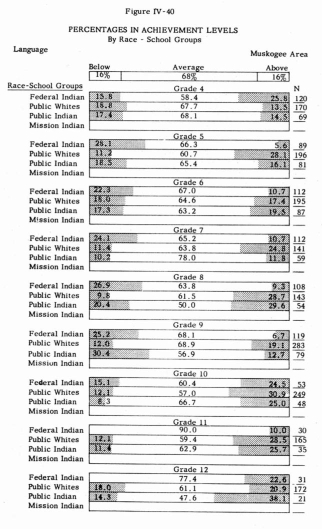

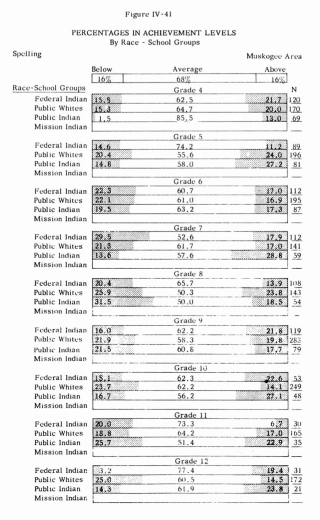

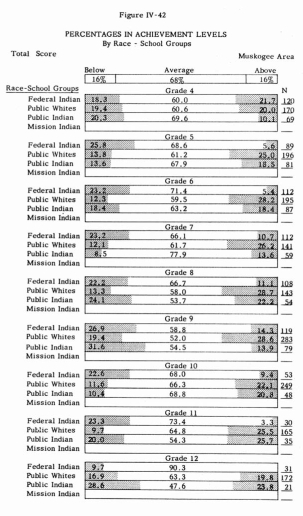

The writers hope that in Figures IV-1 through IV-42 a more meaningful

method of depicting differences in achievement among the several

race-school groups has been found than would result from an examination

of the bare tables of raw-score means. In these figures much the

same scheme is employed as was used in Figures III-4 through III-12

in the preceding chapter. The principal difference is that here

the various race-school groups are compared, within each area,

with the norm group of that area. Such norm groups are composed

of all the children tested in a-given grade in that area. In Figures

III-4 through III-12, it will be recalled, a composite norm group

made up of all the children in a grade in this study was used for

purposes of comparing achievement in the several areas.

Let us use Figure IV-1 as an example. We will consider the middle

68 percent of the scores of all the fourth-grade students who were

tested on reading vocabulary in the Phoenix Area to be average,

the lowest 16 percent to be below average, and the highest 16 percent

to be above average. By comparison, then, we reach the following

conclusion about the white pupils who attended the fourth grade

in public schools: 53.3 percent were average, 18.7 percent were

below average, and 28 percent were above average.

TABLE

4-b

HIERARCHY OF EDUCATIONAL ACHIEVEMENT BY RACE

SCHOOL GROUPS

IN SIX ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS OF THE BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS

PHOENIX AREA

1. White pupils in public

schools

2. Indian pupils in public schools

3. Indian pupils in

Federal schools

4. Indian pupils in mission schools

|

BILLINGS AREA

1. White pupils in public schools

2. Indian pupils in

public schools

3. Indian pupils in Federal schools

4. Indian pupils in

mission schools

|

ABERDEEN AREA

1. White pupils in public schools

2-3 Indian pupils in

mission schools) No significant Indian pupils in public

schools ) difference

4. Indian pupils in Federal schools

|

ALBUQUERQUE AREA

1. White pupils in public schools

2. Indian pupils in

Federal schools

3-4 Indian pupils in public schools )

No significant Indian pupils in mission schools) difference

|

MUSKOGEE AREA

1. White pupils in public schools

2. Indian pupils in

public schools

3. Indian pupils in Federal schools

|

ANADARKO AREA

1. White pupils in public schools

2. Indian pupils in

public schools

3. Indian pupils in Federal schools

|

Variations in Rank and Percentages; Overlapping Achievement of

Pupils

An examination of these figures will reveal that the relative positions

of the several race-school groups differ from the general hierarchy

on certain skills and in certain grades. It will further disclose

that the percentages of pupils who are average, or above or below

average, differ for each race-school group from skill to skill

and from grade to grade. And, finally, the reader will observe

the overlap in level of achievement among pupils of the different

groups, with some pupils in each group achieving; higher or lower

than some pupils in each of the other groups.

IMPLICATIONS OF THE GENERAL HIERARCHY

What are some of the implications of the general hierarchy of achievement

of the race-school groups? An obvious one is that generally the

basic skills of Indian pupils are not yet as well developed as

arc those of White children. This is not a new finding for the

studies by Peterson2 and by Anderson,3 et al, revealed the same

thing.

In general, also, Indian children attending public schools achieved

hither in the laic skills than did those attending Federal or mission

schools, although notable exceptions to this pattern have been

observed in the Albuquerque and Aberdeen Areas. What account for

the general superiority in achievement of public school Indian

pupils over the other two groups? Is it because the public schools

arc “better” schools? Are public school Indian pupils “better

taught?” There are always persons who are quick to leap to

such a conclusion even though no reputable accrediting agency evaluates

the quality of a school on the basis of the scores its pupils make

on a standardized achievement test. Accrediting agencies recognize

that in different schools the pupils themselves may vary widely

in point of cultural background. Accrediting agencies, rather,

establish certain evaluative criteria,4 concerning such things

as professional training of teachers, curricula, and teaching materials,

which they believe to be the hallmarks of a good school. To the

extent that a school measures up to these criteria, or falls short

of them, it is considered a good school or a poor one.

The Quality of the School

Of course, some schools are of much better quality than others.

These differences are very wide and they occur over the entire

United States ill all types of schools. Usually the duality of

the school is of the sort that the people of the local community

demand and can or will pay for. To assume, however, that a school

of a given administrative type possesses or lacks qualities of

excellence, per se, is to stray far wide of the mark.

Difference in Cultural Background

Some differences in cultural background of the three Indian groups

in this study will be discussed in detail in Chapter VI. These

differences, in the opinion of the writers, have more to do with

level of achievement than does mere attendance in a school of a

certain administrative type.

Inter-Area Comparisons

The comparison of achievement of the several race-school groups

need not stop at area boundary lines. It is very enlightening to

make inter-area comparisons. For example, the average achievement

of Indian pupils in Federal schools in the Muskogee and Aberdeen

Areas coincides almost exactly at every grade level. On the other

hand the average achievement of white pupils in public schools

in the Aberdeen Area was significantly higher at every grade level

than that of white pupils in the public schools of the Muskogee

Area. This means, of course, that the white and the Indian pupils

are much more like each other with respect to the basic skills

in the Muskogee Area that they are in the Aberdeen Area.

It is also of interest to note that Indian pupils in Federal schools

in the Anadarko Area achieve on the average at about the same level

as white pupils in public schools in the Albuquerque Area in grades

four through nine. Furthermore, the average achievement of Indian

pupils in Federal schools in the Anadarko Area is at least its

high as it is for Indian pupils in public schools in the Billings

Area in grades four through nine. In turn, Indian pupils who attend

mission schools in the Aberdeen Area achieve on the average at

least as high as public school Indian pupils in the Billings Area

at every grade level. An examination of the tables of mean raw

scores in Appendix C will verify the accuracy of the above statements.

The comparisons made in the two paragraphs preceding are by no

means exhaustive but surely they support the contention that type

of school, alone, is not a controlling factor in determining level

of achievement of pupils.

Some Conclusions

The Bureau of Indian Affairs has committed itself to a policy of'

arranging for the transfer of Indian children from Federal to public

schools as rapidly as is feasible. This transfer has been going

on for many years and is at present being accelerated. One reason

for this is that public education in America has historically and

traditionally been a state, and local function. As Indian people

become integrated with the non-Indian community around them, their

children will attend the schools provided by that community. Furthermore,

it seems logical to suppose that as Indian children associate daily

with non-Indian children they will learn from them. This undoubtedly

happens in most cases.

The logic expressed above is trot necessarily irrefutable ill all

cases, however. The social climate of the school to which the Indian

child transfers needs to be hospitable and sympathetic. Teaching

materials and methods need to be adapted to the needs of the Indian

child if his needs are different from those of his non-Indian classmates.

Otherwise he may he repelled by his school experience rather than

helped by it. In any case the unique contribution which the public

school can make to the Indian child, and which the Federal school

is unable to make, is the opportunity to associate with and learn

from the non-Indian pupils.

It would seem wise for the Bureau to evaluate as carefully as it

can the relative levels of educational achievement and acculturation

of the pupils of both the Federal and the public school before

Indian pupils are transferred from one to the other. By so doing

it might avoid educational and cultural gaps which tend to operate

against the success of Indian pupils and may contribute to their

dropping out of school.

1 At the .01 level of confidence.

2 Shailer

Peterson. 1948. How Well Are Indian Children Educated: Haskell

Institute Press.

3 Kenneth E. Anderson, E. Gordon Collister and Carl E. Ladd.

1953. The Educational Achievement of Indian Children.

Haskell Institute Press.

4 For example, the Evaluative Criteria established by the Cooperative Study of

Secondary School Standards and used by

such accrediting agencies as the North Central Association of Colleges and Secondary

Schools.

|