The Indian Child Goes To School

CHAPTER VI

THE INFLUENCE OF CULTURAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL

FACTORS ON ACHIEVEMENT

In

Chapter IV we observed that the race-school groups of pupils

in this study arrange themselves into a general order or hierarchy

of achievement. This order

is:

1. White pupils in public schools

2. Indian pupils in public schools

3. Indian pupils in Federal schools

4. Indian pupils in mission schools

What light can he shed on the causes of these differences? In this chapter we

will investigate separately the relationship of a number of cultural and

environmental factors to achievement. The investigators felt that these were

some of the factors which might influence achievement. It was recognized.

of course, that there are other such factors not dealt with in this study; for

example, individual intelligence. Since it has not been possible to hold all

other factors constant while. investigating a single factor, we are not in a

position to say positively that the relationship of any one factor to achievement

is one of cause and effect.

Before proceeding, however, three points need to be made clear. First, there

were great differences in level of achievement among individual pupils in the

same area, in the same type of school, and of the same race. For that matter,

these individual pupil differences were usually large within the same grade

of the same school. Basically, however, we are not treating differences between

individual pupils in this study, although Chapters VII and VIII will he devoted

to describing ways of determining individual pupil differences and taking effective

action in the light of such knowledge. Second, there were undoubtedly marked

differences in the level of achievement among the individual schools participating

in the study, hut the data are not treated in such a way as to differentiate

among individual schools. This could he done from the data at hand and it is

suggested that it should he done whenever a transfer of the pupils of one of

the participating schools to another is contemplated in the future. Third,

the differences we are discussing here are characteristic of large groups of

individual pupils enrolled in a large number of individual schools. We are concerned

with the factors related to such differences in achievement because we believe

that by studying them we may better understand the factors which influence the

learning of children everywhere.

It scarcely can he doubted that there were wide differences in the quality of

the schools that participated. Teachers are not all equally well trained and

equally effective. Some schools have better planned curricula than do others.

The teaching materials and equipment in one school may be much superior to those

in another. Furthermore, the writers are entirely convinced that the quality

of a school and its instructional program has much to do with how well or how

much its pupils learn. It must he pointed out, however, that differences which

are wholly individual in character, whether of pupils, teachers, or schools,

probably tend to approach a normal distribution when taken together for an entire

administrative area of this study. The good quality of some will counterbalance

the poor quality of others.

Still we are faced with the hierarchy of achievement of race-school groups set

out at the beginning of this chapter. What thread of influence runs through these

groups and accounts for these rather clear-cut differences? It might be

supposed, as was pointed out in Chapter IV, that the instructional programs of

the three administrative types of schools differ markedly enough from each

other in quality to account alone for the differences in achievement. One fact

stands as a bar to such a conclusion. If the instructional program of the school

alone controls the level of achievement of pupils, why do Indian children who

attend public schools not achieve as high as do white children who attend

public schools? And yet they do not do so in any one of the six administrative

areas included in this study.

DEGREE OF INDIAN BLOOD AND PRE-SCHOOL LANGUAGE

Manifestly, we must look beyond the instructional programs of the schools for

an explanation of the differences in achievement among the race-school groups.

What of the pupils themselves? Are the pupils who comprise the various race-school

groups different from each other, on the average, in any basic respects? An examination

of Tables 6-a through 6-g will disclose that in two particulars they are strikingly

different from each other

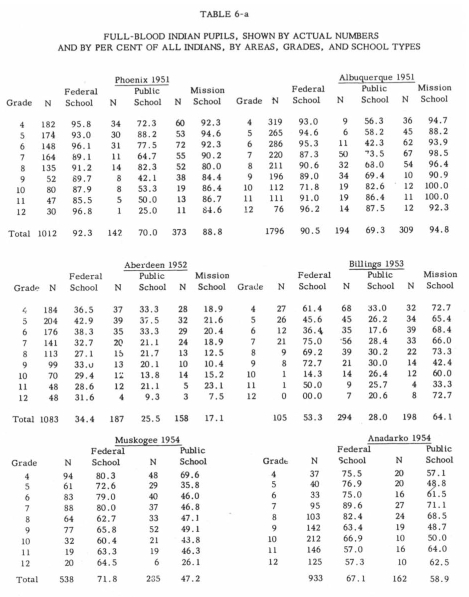

Table 6-a shows the percentages of full-blood pupils in each of the three Indian

groups: Federal school, public school, and mission school. In each of the six

administrative areas a smaller percentage of the Indian pupils attending public

school were full-bloods than was true for either Federal or mission schools,

with one exception. This occurred in the Aberdeen Area where the mission schools

enrolled a smaller proportion of full-bloods than did either the Federal or public

schools. In the Albuquerque and Billings Areas the mission schools enrolled an

even higher percentage of full-blood pupils than did the Federal schools, and

in the Phoenix Area the proportion was very little lower.

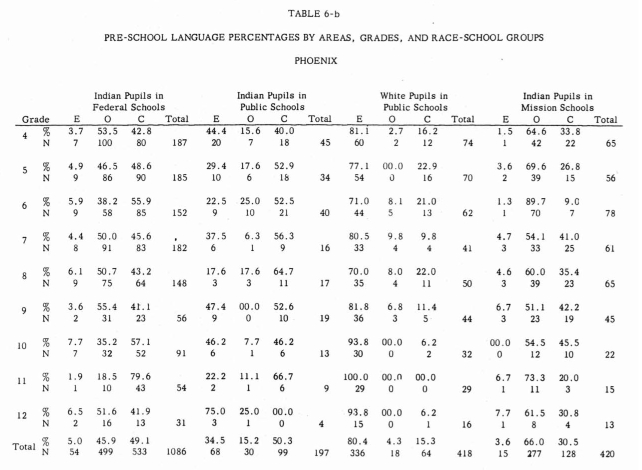

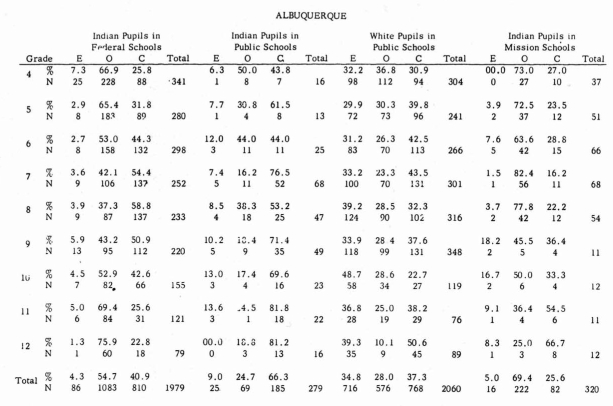

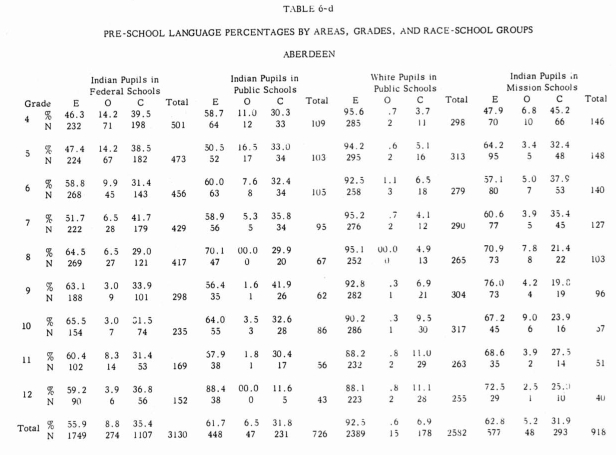

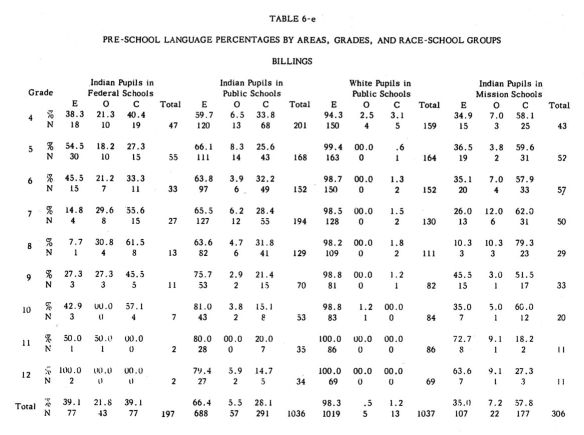

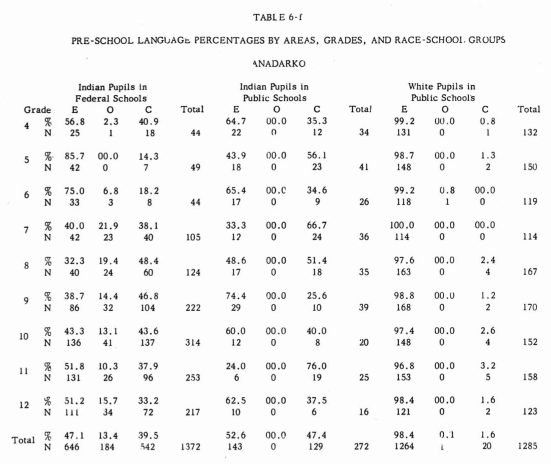

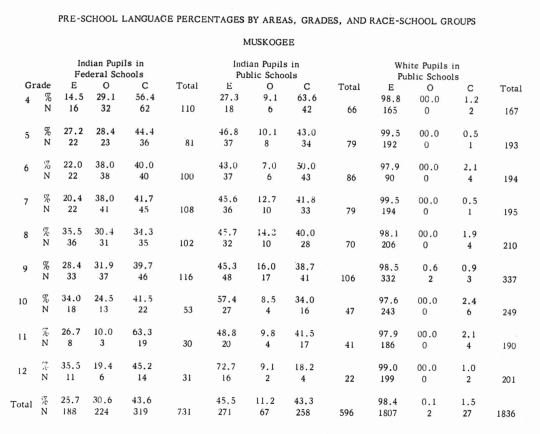

Tables 6-h through 6-g show in percentages, by areas and by grades, the pre-school

language spoken by each of the race-school groups. Without exception a larger

percentage of Indian pupils in public schools spoke only English and a smaller

percentage spoke only some other tongue than was true for Indian pupils attending

Federal schools. As a general rule even fewer Indian pupils attending mission

schools spoke only English and more spoke only some other language, prior to

school entrance, than was the case with Indian pupils attending Federal

schools. Again, a notable exception to this rule occurred in the Aberdeen Area

where the situation was reversed. In all areas except Albuquerque a great preponderance

of the non-Indian children spoke only English prior to school entrance and a

minute percentage spoke only some language other than English. Even in the Albuquerque

Area a far higher percentage of the non-Indian pupils in the public schools spoke

only English prior to entering school than was true for any of the Indian groups.

Thus, on the bases of full-blood pupils and pre-school language the race-school

groups arrange themselves into hierarchies which coincide with the hierarchy

of achievement. That is, the higher achieving groups enrolled a smaller

percentage of full-blood pupils, a smaller percentage of pupils not speaking

any English prior to school entrance, and a higher percentage of pupils speaking

only English prior to starting to school.

Degree of Blood and Pre-School Language as Indices of Acculturation

It should be made clear that the writers do not believe that blood quantum and

preschool language in themselves are strong determiners of achievement.

They do believe that these two characteristics are excellent indices, on the

whole, of the stage of acculturation of the groups of pupils. Finally, they believe

that the extent to which a family or community has integrated itself with the

dominant culture of the nation has a very great influence upon the school achievement

of its children.

The foregoing statement needs clarification in several respects. Many full-blooded

Indians are completely acculturated and have reached a high level of sophistication.

In general, however, it is probable that the white person, or the person

of mixed-blood has had greater opportunity to acquire the attributes of the major

culture, of which knowledge of the English language is one, but only one.

There is evidence available which indicates that by the fourth grade level the

school may he successful in overcoming in large part the pupil’s handicap

of lack of pre-school English in learning the basic skills. Later on, however,

and particularly by grade six, the same pupils may again fall farther behind

their classmates who come from English-speaking homes.1 It

must be remembered that the influence of the home and community on the child

does not cease when he enters school. If he returns each evening to

a home in which English is not spoken he will get no help and scant encouragement

there in developing English skills. Up until grade four, for example, all

pupils are developing verbal and numerical skills which are very basic to their

everyday needs and common experiences. In the higher grades, however, the learning

experiences involve concepts which are more abstract and farther removed from

the everyday needs of the learner as he feels them. If the home, or the community

for that matter, is not able to keep pace with these expanding learning situations

in the school, it can contribute little to the learning process.

Defining “Acculturation.” We often use the term “acculturation” as

if its meaning must be clear to anyone hearing it. This certainly is taking too

much for granted. There is an obligation to define “acculturation” as

it applies to pupils in this study. A dictionary definition of acculturation

is, “the process and result of adopting the culture traits of another group.” Without

presuming to treat the subject exhaustively, it may be helpful to cite some

examples of traits which are felt to be characteristic of the major part of

the population

of the United States and which the lower achieving groups in this study probably

possess in lesser degree than do the higher achieving groups.

I. Habitual use of spoken and written English in the home and community as a

means of communication. The presence of books, magazines, a daily newspaper,

radio, and perhaps television in the home.

2. Regular, useful, and gainful employment of the bread-winner of the family.

The possibility of the children of the family looking toward adulthood with confident

expectation of desirable employment opportunity.

3. Participation with one’s neighbors in the educational agencies

of the community, other than schools, such as the churches, Scouting, and

4-H clubs.

4. Participation by adult members of the family in civic and community affairs

such as voting, active membership in service clubs, veterans organizations, farmers

cooperatives, etc., to mention only a few.

5. A reasonably good understanding of and concern for proper diet and health

practices, particularly as they concern the younger members of the family.

6. Acceptance of a set of values which attaches importance to such traits as

industry, thrift, punctuality, acquisitiveness, competitiveness, and independence.

(Whether all of these traits are virtuous, especially when carried to an extreme,

may be debatable. It is felt that they are typical of the major culture of the

country.)

How Acculturation Is Accomplished. It must be obvious that the above list could

be expanded, almost ad infinitum. It is clear, however, that even the six points

listed are not solely within the immediate control of the school. The writers

would be the first to place the school at the head of a list of acculturative

agencies of society. The benefits of education, however, find their most

effective expression in home and community life. Usually it is only after the

pupil himself has reached adulthood and becomes the head of a family that his

education makes itself felt in changing culture patterns. Thus, generation by

generation the process of acculturation progresses. This “delayed action” type

of progress is frustrating to those persons who impatiently expect people to

be “made over in a day” and who seem to believe that if the schools

are run effectively this should be possible.

Furthermore, however well the schools may do their job, the task of helping Indian

people to achieve lull status in American life calls for cooperative effort on

a broad front. It

is neither the prerogative nor the desire of the writers to lecture the Indian

people concerning any obligation on their part to acquire the traits of

the dominant culture. The writers feel they should point out, however, that Indian

people face an alternative—perhaps a hard one. For except as Indian people

embrace the major culture it seems unlikely that their children, on the

average, will learn as well or as much in their school subjects as do white children.

Nor is the problem unilateral in its aspects. Non-Indian people cannot reasonably

expect that Indian people will enthusiastically embrace the major culture unless

they arc encouraged and helped to do so.

Reconciling Two Exceptions to the General Hierarchy of Achievement

How can the two exceptions to the general hierarchy of achievement of race-school

groups be explained: namely, the relatively high position of mission school pupils

in the Aberdeen Area and of Federal school pupils in the Albuquerque Area So

tar as the Aberdeen Area is concerned, the fact that mission school pupils

achieved at a higher level than Federal school pupils, and at least as high as

public school Indian pupils, is perfectly consistent with the main premise

set forth in this chapter thus far. That is, the mission schools in the Aberdeen

Area enrolled a smaller percentage of full-blood Indian pupils than did either

the Federal or public schools. Furthermore, a larger percentage of mission school

Indian pupils spoke only English prior to school entrance, and a smaller

percentage spoke only another tongue, than was true of either Federal or

public school Indian pupils.

The relatively high achievement of the Federal school pupils iii the Albuquerque

Area does not yield to such a ready explanation. Here the Indian pupils in Federal

schools achieved significantly higher than did the Indian pupils in public schools.

Also, there was no significant difference between the level of achievement of

public school Indian pupils and those in mission schools. No objective data can

he adduced to account satisfactorily for this departure from the typical hierarchy

as described in Chapter IV. A substantially higher percentage of the Federal

school pupils were full-bloods than was true for the public school Pupils.

The mission schools enrolled a higher percentage of full-blood pupils than did

either of the other types of schools. Also, a much lower percentage of public

school Indian pupils spoke only some language other than English, prior to school

entrance, than was true of either Federal or mission school Indian pupils.

Without question the Federal schools of the Albuquerque Area (now the United

Pueblos Agency) enjoy certain advantages not shared by those of some of

the other areas. First, the Pueblo villages were fairly compactly located with

respect to area headquarters, facilitating effective supervision of the

schools. The education staff of the Bureau has taken full advantage of this circumstance

to do excellent work in the supervision of instruction, cooperative curriculum

planning and preparation of teaching materials, and in evaluation of the educational

program. Second, the Pueblo people live in villages, immediately adjacent to

which the Federal day schools have been placed. The Pueblo People have had for

centuries a relatively stable culture and a closely knit community organization.

As a result the day schools have become closely integrated with village community

life. One result of this has been that the average daily attendance of the Federal

day schools approaches a highly satisfactory 94 percent, as disclosed by

attendance records independent of this study.

It may be important to note that the non-Indian pupils in the public schools

of the Albuquerque Area differ markedly in one respect from any other non-Indian

group in this study. Twenty-eight percent of them spoke only some language other

than English before starting to school (mostly Spanish) and 37.3 percent spoke

a combination of English and some other language. Only 34.8 percent spoke only

English prior to school entrance. They were the lowest achieving of all the non-Indian

public school groups in the study, although they achieved significantly higher

than any of the Indian groups in the Albuquerque Area. One can only speculate

as to whether they exercised less acculturative influence on their Indian classmates

in the public schools than did their non—Indian contemporaries in the other

areas.

AGE OF PUPILS IN RELATION TO GRADE

On the average, Indian children are older for their grade than are white pupils.

Age-grade data in this study reveal that, in general, the average age of Indian

pupils in Federal schools was slightly more than a year greater than that of

white children in public schools in the same grade. Indian pupils in public schools

were approximately six months older, on the average, than their white classmates,

while Indian children in mission schools were, in general, nearly a year older

than white pupils of the same grade in the public schools. These findings are

very similar to those of Peterson2 in 1946 and of Anderson3, et al, in 1950.

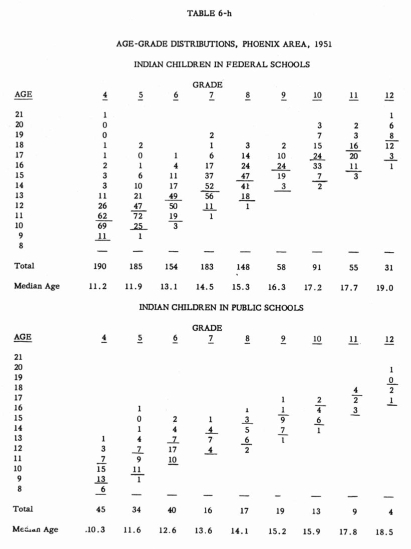

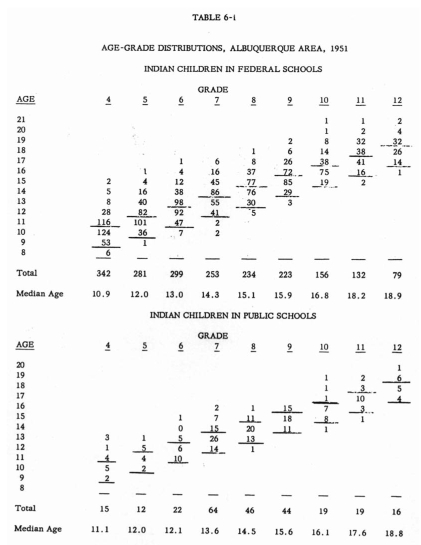

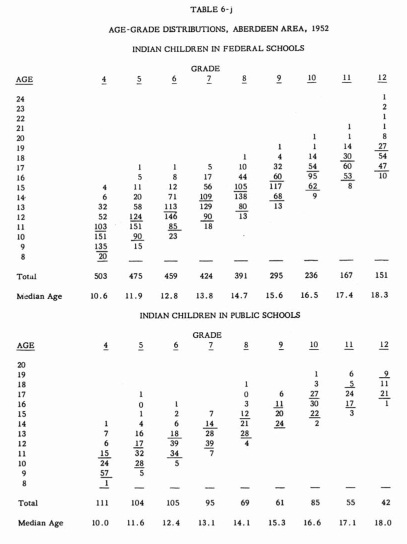

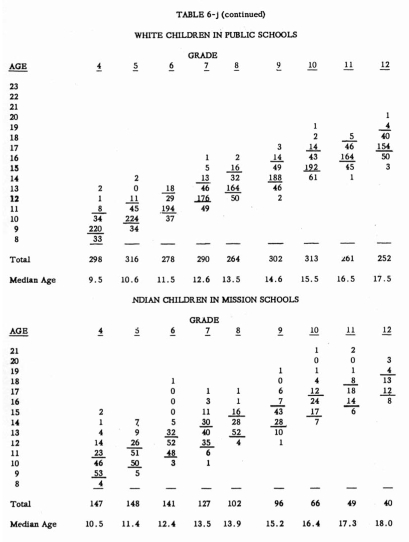

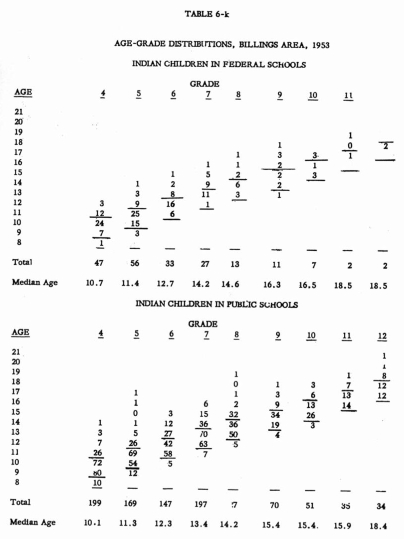

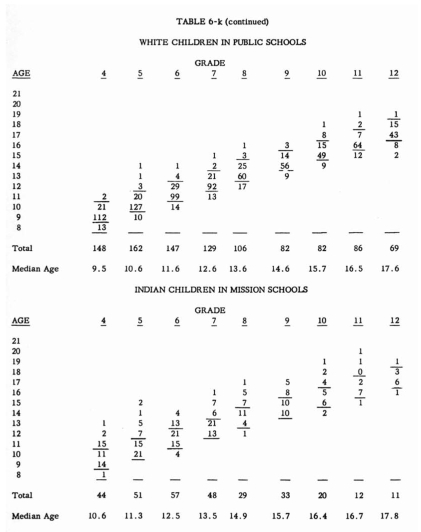

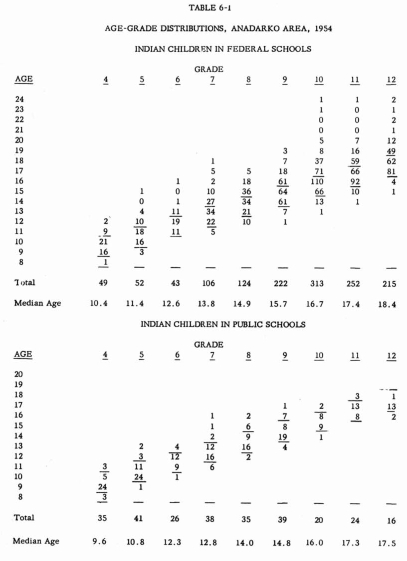

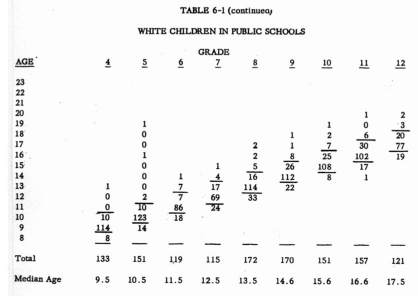

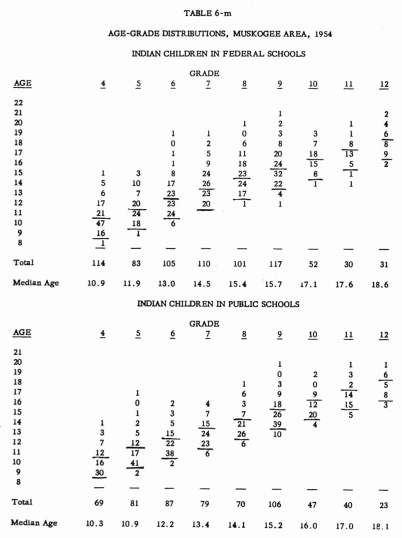

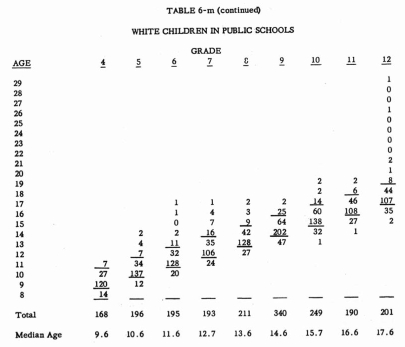

Tables 6-h through 6-rn show the distribution of pupils in the study by age and

by grade for each of the six areas. Pupils falling within the normal age range

for a grade are set off by the staggered lines. The determination of what is “normal” age

for a grade was based mainly on the data themselves. Ages nine and ten included

more fourth-graders (the lowest grade in the study) than did any other two successive

ages. Fourth-grade pupils who were either nine or ten years old at the time the

tests were given were thus identified as “at grade” for their age.

Those who were older or younger were identified as “over-age” or “under-age”,

respectively. By a regular progression. normal ages for each of the succeeding

grade levels were determined by adding one year for each grade. Tables 6-h through

6-rn also show a median age for each race-school group, for each grade in each

area.

The average over-ageness of Indian pupils as compared with white pupils was not

the same in all of the areas. For Indian pupils in Federal schools it was greatest

in the Phoenix arid Muskogee Areas and least in the Albuquerque Area, ranging

from about one year and four months for the former to about eleven months for

the latter. For Indian pupils in public schools it was greatest in the Aberdeen

Area and least in the Anadarko Area, with a range from approximately nine months

to about four months. The greatest over-ageness for Indian pupils in mission

schools occurred in the Phoenix Area and the least in the Aberdeen and Albuquerque

Areas, ranging from about one and a half years to about nine months.

Some Reasons for the Over-ageness of Indian Pupils

It should be remembered that bate entrance into school accounts for some. but

by no means all of the over-ageness of Indian pupils. For those pupils who speak

little or no English prior to school entrance, Federal schools have found

it necessary to require a beginning year. During this year skills in spoken English

are developed and the child is helped to acquire a background of experience

which will make formal instruction in the basic skill subjects, beginning

with grade one, more meaningful to him. Presumably public and mission schools

which enroll children with a similar problem must do much the same things. Undoubtedly

the necessity for this beginning year contributes substantially to the general

aver-ageness of Indian pupils.

Another factor which may account in part for the tendency of Indian pupils to

be older for their grade than white children of the same grade is the frequency

with which Indian children in some localities fail to attend school during

an entire school year. Lack of stability in the social and economic bite of many

Indian families mainly accounts for this. For example. in some localities some

families withdraw children from school for considerable periods of tune

while the adults, and the older children, engage in migrant seasonal labor. The

families need the income from this type of work because of poor resources au

the reservations. but prolonged periods of absence from school may, of course,

necessitate a pupils repeating a grade. School authorities are striving hard

to correct this situation by finding means of keeping the children in school

while the adults are away from

home working.

It is not believed that there is any widespread practice, in Federal schools

at least, of retaining a pupil in a grade for a second year because of academic

failure. The writers cannot speak with authority concerning the promotional

policies of public and mission schools.

Other Observations

Referring again to Tables 6-h through 6-rn, it will b~ noted that in general

the range of ages in a given grade was greatest for Indian pupils in Federal

schools and least for white pupils in public school. It will he observed, too,

that generally the range of ages within a grade lessened for each race-school

group from grade four through grade twelve. The writers believe that this

latter phenomenon is brought about largely by the dropping out of school of over-age

pupils as the higher grades are reached.

For the most part, in any grade in any area the concentration of ages for white

pupils in public schools was in one or two years, while the concentration of

Indian pupils in Federal schools was usually in three or four different years.

Although no data relating to the sex of pupils is given in the age-grade tables,

it was observed by the investigators that, regardless of race-school groupings,

the preponderance of pupils who were over-age for their grade were boys and the

majority of pupils who were under-age for their grade were girls.

It appears from the data that, except in the Albuquerque and Phoenix Areas, Indian

and white pupils tend to he more nearly the same age in the eleventh and twelfth

grades than was true for the earlier grades. Again, we find here a suggestion

of heavy drop-out of over-age Indian pupils at the highest grade levels.

The Relationship Between Age in Grade and Achievement

A study of the data reveals, furthermore, that there is a definite relationship

between the over-ageness or under-ageness of the pupils in this study and their

achievement in the basic skill subjects. There is impressive evidence that, on

the average, those pupils who were over-age for their grade did not make as high

scores on the tests as did the pupils who were of normal age for their grade.

The data indicate, somewhat less conclusively, that in general the pupils who

were under-age for their grade did somewhat better on the tests than did those

falling within the normal age range. A word of explanation and of qualification

about this latter statement is necessary and will he given later.

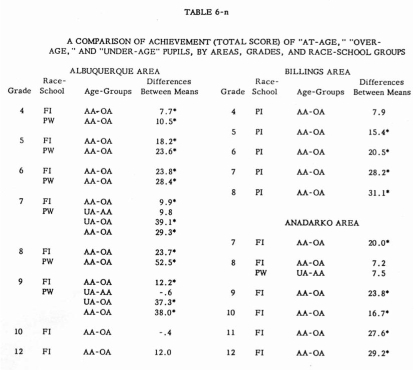

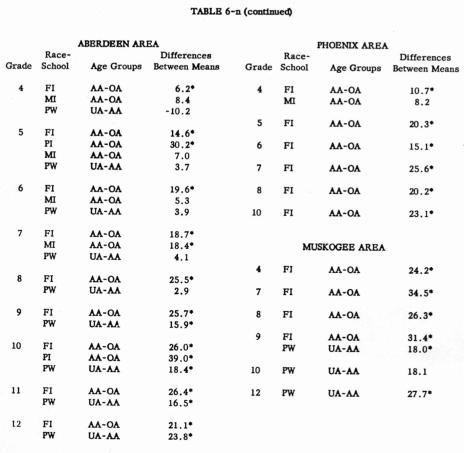

A comparison of the achievement of at-age, over-age, and under-age pupils, on

total score only, was made for each area, in each grade, and for each race-school

group whenever the number of pupils in a 4atcgory was large enough to insure

a reasonable degree of reliability. No comparison was made when the number of

pupils in a category fell below thirty. Table 6—n shows the results of

these comparisons. It will be noted that the table shows the differences between

mean scores for various pairs of age groups. The mean score of the second group

has been subtracted from the mean score of the first group.

In all it was possible to make sixty-eight comparisons. Of these, fifty-one were

comparisons of over-age pupils with those who were at-grade for their age.

Of the fifty-one comparisons, forty-three showed that pupils who were of normal

age for their grade achieved significantly higher on the average than did those

who were over-age. In only one instance (tenth grade in Federal schools of the

Albuquerque Area) did over-age pupils actually make a higher average score than

pupils who were at-grade for their age.

Differences between means are of total raw score and were obtained by subtracting

the mean of the second group from the mean of the first. All differences except

those preceded by a minus sign indicate that the first group in the comparison

had the higher average or mean score.

*Significant at or beyond the .05 level of confidence. (Apparent inconsistencies,

in that some differences are not significant whereas smaller differences are,

are attributable to the smaller number of pupils in a group. For these numbers

refer to Tables 8-h through 6-m.)

Of the remaining seventeen comparisons, fifteen compared the achievement of under

age pupils with thos of normal age. Of these, six showed the under-age pupils

to be significantly higher. In only two of the fifteen comparisons did the at-age

pupils actually make higher average scores than those who were under-age.

The remaining two comparisons were of under-age and over-age pupils. In both

of these the under-age pupils were significantly higher.

Except in the Albuquerque Area, all of the over-age comparisons were of Indian

children. Without exception time under age comparisons were of white pupils.

It must he noted that most of time pupils who are here classified is under-age

would not be considered so in many, or perhaps in most, of the schools of the

nation. The normal age-grade range as defined in this study is perhaps one year

higher than in the typical school. Therefore, there is no justification whatever

for concluding that starting children to school at an unusually early age or

accelerating them unduly helps them to learn.

The writers do not believe that over-ageness in itself is the sole contributor

to the tendency of over-age pupils to achieve less well than those of normal

age. It is probable that social, economic, and cultural factors in the home and

community which may have caused the pupil to be over-age in the first place will

continue to operate against his learning, It is true, however, that being over-age

for his grade may hamper a pupil’s social adjustment in the school and

cause serious loss of interest in motivation.

Once again, the reader should bear in mind that we have been speaking in terms

of averages. There were, of course, some over-age pupils who achieved higher

than some pupils who were of normal age for their grade.

The “Holding Power” of the School

One of the perennial concerns of the school is its “holding power.” However

effective or ineffective the program of the school may be in educating the child,

it obviously can do nothing for him if he is not present. It therefore behooves

any school to examine its “drop-out” problem closely – to see

whether it is alarmingly high and to determine, if it can, why children drop

out of the school prior to the completion of the twelfth grade. Incidentally,

it is often very difficult to determine the true reasons for a pupil’s

dropping out of school. Inevitably, since Indian children attend three different

types of schools, there is considerable interest as to which type does the best

job of holding Indian children in school.

Unfortunately the data in this study are not of such a mature as to throw much

light on this question. There are several reasons for this:

(a) The data were all gathered in a given year for a given area and thus do not

represent thc progression of the same children from grade four toward or through

grade twelve.

(b) The increasing in influx of students into the lower grades, typical of the

country as a whole in recent years, is not taken into account.

(c) In organizing the study, there was no attempt to control closely the selection

of participating schools with the dropout question in mind. To have done so would

have seriously handicapped the study in other important respects. The general

aim was to test all children in Federal schools in an area and approximately

the same number of pupils in public and mission schools combined. Public schools

enrolling a considerable proportion of Indian pupils, and operating in the same

general localities as Federal schools, were invited to participate. Participation

was entirely voluntary, however, and depended largely upon the interest of public

school administrators and teachers.

Examples of unusual enrollment situations which resulted were:

(1) In many communities public high school pupils are bussed in from smaller

rural communities which operate their own elementary schools and which may not

have participated in the study. This served to make the hij1h school enrollment

larger by comparison with elementary enrollment than it would normally be. The

Aberdeen, Muskogee, and Anadarko Areas offer excellent illustrations of this.

On the other hand, an opposite situation might exist: the elementary school may

have participated in the program whereas the high school in another community

to which the pupils are bussed did not.

(3) Indian children often transfer from Federal day schools or public schools

to Federal boarding schools, sometimes in a different area. For instance, Flandreau,

in the Aberdeen Area, enrolls pupils from the Billings Area; Chilocco and Haskell,

while administratively in the Anadarko Area, enroll many pupils from the Muskogee

Area.

(3) There is always some transferring of pupils among public, mission, and Federal

schools at all grade levels.

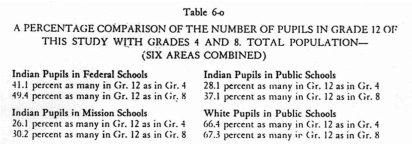

Nevertheless, with due regard for the limitations mentioned above, there are

indications from the data that Indian children the country over are not

staying in school to the completion of their high school education in as large

proportions as do white children. The data shown below seem to support this conclusion.

In 1950 there were 49.8 percent as many twelfth-graders as fourth-graders for

the country as a whole and 77.7 percent as many twelfth-graders as eighth-grade

pupils.4 These percentages for the Indian population in this study are well below

that. They are shown in Table 6-o, below.

Unquestionably the “holding power” of the school for Indian pupils

is a matter of severe educational concern. A need for a much more rigorous and

exhaustive survey of this problem is indicated.

RESIDENCE ON OR OFF A RESERVATION

There is strong evidence that Indian pupils who live on a reservation do not

achieve as well in the basic skills, on the average, as those who do not. This

comparison was made on total score only, by areas, by grades, and by race-school

types. Again, for reasons of reliability no comparison was made when the

number of pupils in any category fell below thirty. As a result, no comparisons

were possible in the Albuquerque, Billings, and Phoenix Areas for time reason

that there were not enough pupils whose homes were off Indian reservations.

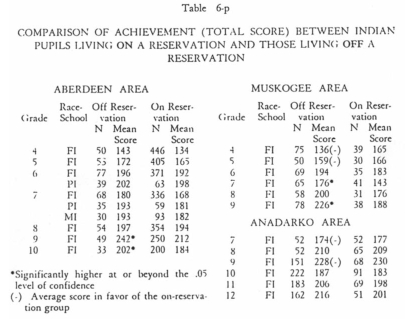

Comparisons which could be made in the Aberdeen, Anadarko, and Muskogee Areas

are shown in Table 6-p.

In all, twenty-two comparisons were possible. Ten of these were in the Aberdeen

Area with six each in the Anadarko and Muskogee Areas. All but three of the twenty-two

comparisons were of Indian pupils in Federal schools; two were o Indian pupils

in public schools amid the remaining one was of Indian pupils in mission schools.

Only four of the separate comparisons revealed differences which were statistically

significant. All four of these showed Indian pupils living off reservations to

be higher. This evidence taken alone would not he very conclusive. However, it

was observed that in only four of the twenty-two comparisons did Indian pupils

living on a reservation actually make a higher average score than those living

off. This was true for two of six comparisons in the Anadarko Area and for two

of six in the Muskogee Area. In the Aberdeen Area the “off-reservation” groups

were unvaryingly higher. How likely is it that the apparent superiority

of the “off-reservation” group occurred by chance alone? Statistical

investigation5 revealed that this probability was less than one in two hundred,

either for the three areas combined or for each area taken separately. This finding

greatly strengthens the conclusion that Indian pupils who live on reservations

do not achieve as high on the average as those who do not.

RESIDENCE IN A TOWN OR IN THE COUNTRY

We may conclude from this study that, in general, pupils who live in a town achieve

higher in the basic skills subjects than do those who live in the country.

Pupils in this study were asked whether they lived in a city or town or in the

country. Comparisons were then made between the city-town groups and the

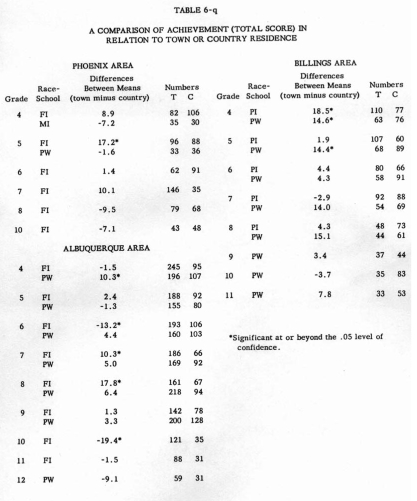

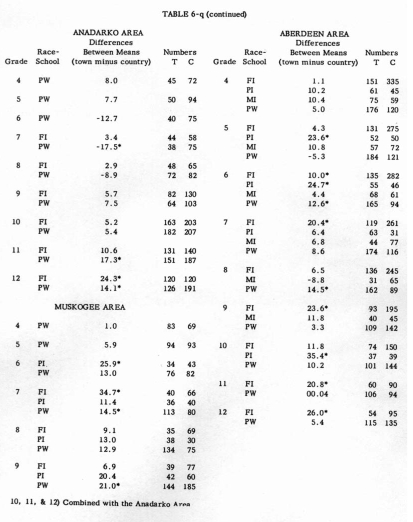

country groups on the basis of achievement (mean total raw score). Table 6-q

shows the results of these comparisons by areas, grades, and race-school groups.

It also shows the number of pupils in each category.

In all, ninety-three separate comparisons were possible, after meeting the requirement

of a minimum of thirty pupils in a category in the interests of reliability.

Of these. seventy-six produced differences which were in the direction of the

town pupils; only seventeen differences were in the direction of the country

pupils. Twenty-four of the seventy-six differences favorable to the town

pupils were statistically significant. Only three of the seventeen differences

in the direction of the country pupils were significant.

The ninety-three comparisons were divided among the race-school groups as follows:

white pupils in public schools, forty; Indian pupils in Federal schools, thirty-two;

Indian Pupils in public schools, fourteen; Indian pupils in mission schools,

seven. Regardless of race or type of school, the evidence strongly indicates

the superior achievement of pupils who live in town.

An inspection of Table 6-q will reveal that the superiority of the town dwelling

pupils was not as clear-cut in the Phoenix and Albuquerque Areas as it was

elsewhere. Ten of the seventeen differences favorable to country dwelling pupils

occurred in these areas. We cannot be sure that the slight general tendency of

town dwellers in these areas to be superior in achievement did not occur

by chance. In all other areas, however, and for the study as a whole the higher

average achievement of pupils living in town was highly significant.

It should be pointed out that many of the pupils living in the country attended

school in town, particularly in the high school grades. It is not felt that rural

day schools alone account for the differences in average achievement.

THE CHOICE OF FRIENDS BY INDIAN AND WHITE PUPILS

It has seemed to the investigators in this study that the extent to which individuals

of one race, given opportunity, select their friends from among individuals of

another race is a valuable indication of the stage of social integration of the

two races. The choosing of friends is a very personal matter. Each of the pupils

in this study was asked to check one of the following statements about his friends:

I. all of them are Indian boys and girls; 2. most of them are Indian, some are

white; 3. most of them are white, some are Indian; 4. all of them are white boys

and girls. To help the pupil understand what was meant by “friends,” the

person administering the tests suggested that friends are the persons with whom

we usually play.

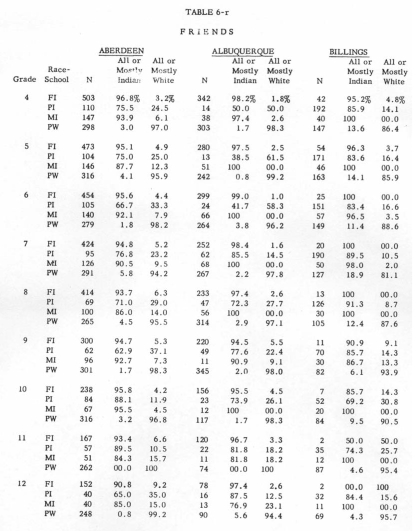

In treating the data. responses to items I and 2, above, were added together,

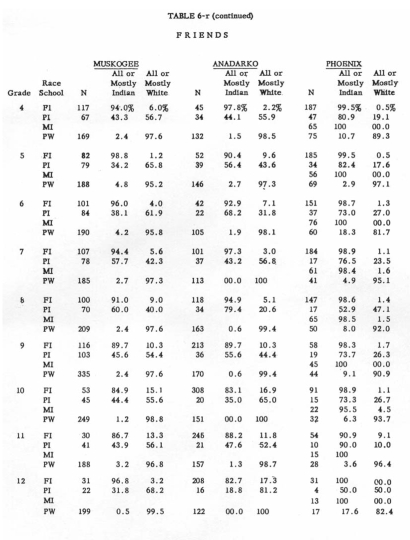

and likewise the responses to items 3 and 4. Table ô-r shows, by areas

and by grades, the percentage of pupils in each race-school group who said their

friends were all or mostly Indian boys and girls and the percentage who said

their friends were all or mostly white boys and girls.

It was to he expected that since the Federal and mission schools enroll few,

if any, white pupils a small percentage of Indian pupils in these schools would

say that their friends were all or mostly white. This proved to be true, although

this percentage does run in excess of IS percent for a few Federal and mission

school groups in some of the areas. Pupils were not expected to interpret “friends” to

mean only those pupils with whom they were currently attending school. Nevertheless

it seems logical to suppose that most of a school child’s friends will

be found among his schoolmates. For this reason we can look to the percentages

in the public schools with added interest. In these schools both Indian and white

pupils were attending although not usually in equal proportions.

In the Phoenix Area the number of public school pupils was small, with the ratio

of white pupils to Indian pupils in most grades running two or three to one.

Still, about three-fourths of the Indian pupils said their friends were all or

mostly Indian; about 90 percent of the white pupils said their friends were all

or mostly white.

In the Albuquerque Area the average ratio of white pupils to Indian pupils in

public schools was approximately eight to one. In spite of this, except in grades

four, five, and six. more than three-fourths of the Indian pupils said that all

or most of heir friends were Indian. In every grade n-tore than 90 percent

of the white pupils said all or most of their friends were white. This response

by the white pupils is not surprising since there were so few Indian pupils from

whom they could choose their friends.

In public schools of the .Aberdeen Area the ratio of white pupils to Indian pupils

was between three and four to one. Here again a strong majority of the Indian

pupils claimed all or mostly Indian friends while more than 95 percent of the

white pupils said their friends were all or mostly white boys and girls.

Five times as many of the pupils tested in public schools of the Anadarko Area

were white than were Indian. Understandably, in view of the disproportion, not

ti-tore than two percent of the white pupils said that all or most of their friends

were Indian. In the Anadarko Area, however, a majority of the Indian pupils

in grades four, seven, ten, eleven, and twelve said that all or most of their

friends were white. In the other grades the proportion of Indian pupils claiming

all or mostly white friends, while less than half, was substantial.

In general there were between three and four times as many white pupils as Indian

pupils tested in public schools of the Muskogee Area. As expected, more than

95 percent of the white pupils said that all or most of their friends were white.

In all grades except seven and eight, however, a majority of the Indian pupils

said that all or most of their friends were white.

In some ways. the data from the Billings Area are the most revealing. This was

the only one of the six areas in which the numbers of white arid Indian pupils

in the public schools were approximately equal. It is significant, then, that

more than 80 percent of the pupils of each race indicated that all or most of

their friends were of their own race.

It seems fair to conclude that, except in the, Oklahoma Areas, Indian pupils

choose their friends mainly from their own race even though they have an equal

or larger number of white schoolmates from whom to choose. And in the public

schools of the Billings Area. where the proportion of white and Indian pupils

was equal. the white pupils were equally inclined to select their friends from

their own race.

The Relationship Between Choice of Friends and Achievement

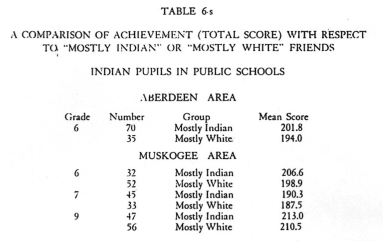

An attempt was made to compare the school achievement of Indian pupils who said

that all or most of their friends were white children with those who said they

had all or mostly Indian friends. The attempt was not very rewarding. Because

of insufficient numbers of Indian pupils claiming all or mostly white friends,

comparisons were possible only for Indian pupils in public schools in the sixth

grade of the Aberdeen Area and in grades six, seven, and nine of the Muskogee

Area. Table 6-s shows the results of these Comparisons. None of the differences

in mean total score was found to be statistically significant. On the basis

of these findings there is not sufficient evidence for accepting the hypothesis

that Indian pupils who has e mainly white friends achieve better in school than

those who do not.

There is no reason for concluding from the data that Indian children do not achieve

better by reason of attending school with white children. The data do not bear

upon that point. It must be remembered that the question concerned “friends”—not

associates or schoolmates. Few of us consider every associate a “friend” in

the close, intimate connotation that the term usually carries. One may be able

to learn from associates without feeling that they are close friends.

What is revealing is the evidence that the integration of the children of two

races in a school in the bare sense of attendance does not necessarily lead.

Immediately at least, to a type of social integration which will cause pupils

to choose their friends without regard to race.

THE PROPORTION OF WHITE PUPILS IN THE SCHOOLS ATTENDED BY INDIAN PUPILS

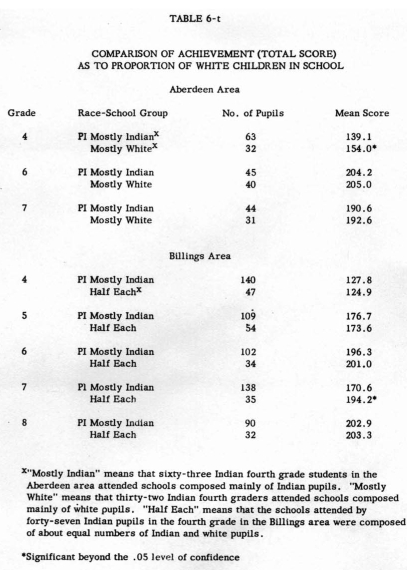

An investigation was made of the school achievement of Indian pupils in relation

to the proportion of white pupils in the schools they attended. The background

data for each pupil indicated whether the school he attended was made up of:

1. only Indians; 2. mostly Indians; 3. halt Indians. halt whites: 4, mostly whites:

5, only whites. In treating the data. 1 and 2, above were combined and designated

as mostly Indian” and 4 and 5 were combined and designated as “mostly

white.”

Obviously there were no Federal or mission schools which enrolled “mostly

whites” or even “half Indian, half white” since the main reason

for the existence of such schools is the education of Indian youth. Consequently

such comparisons as could be made were entirely of Indian pupils attending

public schools . All public schools in the study enrolled some Indian pupils

else they would not have been included. In some of these schools most of the

pupils were Indian. .As usual, a minimum requirement of thirty pupils in a category

was adhered to before comparisons were made.

on the average on total score than

those attending “mostly Indian” schools. Differences in grades six

and seven were in the direction of the pupils attending “mostly white” schools

but they did not differ significantly.

In the Billings Area comparisons were made in grades four through eight between

the average achievement of Indian pupils attending public schools which were “mostly

Indian” and that of pupils attending schools that were ‘half Indian,

half white.” Only one of these differences was found to be statistically

significant. This was in grade seven iii which the pupils attending schools which

were “half Indian, halt white” scored higher on the average than

those in the “mostly Indian” schools. In grades tour and five the

differences, although in the direction of the “mostly Indian” schools,

were not significant.

In all, the data are not very impressive. There is a slight indication that Indian

pupils attending public schools enrolling a large proportion of white pupils

achieve better than those attending public schools with mostly Indian pupils

but the evidence is by no means conclusive. Combining the probabilities yields

a result lower than that which statisticians usually require before attaching

significance to a difference.

REGULARITY OF ATTENDANCE

To most persons, and certainly to most teachers, it has been a foregone conclusion

that regular attendance in school is an essential ingredient in a pupils scholastic

success. To these persons it may seem a waste of time and effort to investigate

the relationship between school achievement and regularity of attendance. The

investigators were interested in bringing objective data to bear upon this question,

however, for precisely the reason that it is so seldom done. The data do show

clearly that, in general, pupils who attend school regularly learn more in the

basic skills measured than those who do not. The evidence is remarkable

mainly in that it is not more conclusive than it is.

The investigation concerning regularity of school attendance was confined to

the day schools of the Aberdeen Area. distances are great in North Dakota and

South Dakota and the winters are long and hard. Roads and weather often conspire

against a child’s getting to school in the morning. In addition, many of

the Indian people in this area engage in seasonal labor of the migrant type which

takes them away from their homes, particularly in the early weeks of the school

year. It was felt that hoarding schools do not encounter attendance problems

to the same degree as do day schools.

Table 6-u shows the relationship between regularity of attendance and school

achievement in the day schools of the Aberdeen Area. The data are shown by grades

and by race-school groups. These are subdivided, further, into two groups on

the basis of regularity of attendance and a comparison made of their mean

total score on the test battery. A distribution was made of the number of days

of absence for each separate race-school group within a grade and the median

number of days absence for the group was computed. This resulted, of course,

in au approximately equal division of each group. For example, for Indian pupils

in Federal schools in grade four, the median number of days of absence per pupil

was between fifteen and sixteen. A comparison was then made of the average achievement

of those pupils who missed fifteen days of school or less with that of those

who missed sixteen days of school or more. The mean difference was bound to be

4.6 raw score points. This difference, taken by itself, was not statistically

significant.

In all, eighteen separate comparisons were possible. holding to the requirement

of not less than thirty pupils in a group. Of these, four were statistically

significant. It is noteworthy. however, that sixteen of the eighteen differences

were in the direction of the more regular attenders. Neither of the two differences

which were in the direction of the irregular attenders was statistically significant

. A combining of probabilities of the eighteen differences reveals that, in general,

the superiority of achievement of regular attenders over irregular attenders

is highly significant. Nevertheless, the margin of superiority of irregular

attenders

over those who were more regular. among seventh-grade

Indian pupils attending public schools, may prove surprising to many readers.

It should be said that this was the smallest of all the groups with exactly thirty

pupils in each category. Differences within the group, of factors other than

attendance, apparently overcame the tendency of regular attenders to achieve

higher than those who were irregular.

It will be noted that the greatest absence was among Indian pupils attending

Federal schools, the next greatest among Indian pupils attending public

schools id the least among white pupils attending public schools. This is not

surprising since, as was pointed out earlier in this chapter, the Federal schools

serve the less acculturated, and presumable the more isolated portion of the

Indian population. Since the mission schools in the Aberdeen Area are mainly

of the boarding type. no comparisons involving mission school pupils were possible.

It is recognized that, whereas the attendance data for each pupil was gathered

for only one school year, every year of the pupil’s school experience up

to the time of testing had influenced his achievement test scores. It seems reasonable

to suppose, however, that. having prolonged illness or other unusual circumstances,

the pattern of attendance of most pupils is probably fairly consistent from year

to year.

Finally, it must he borne in mind that regularity of attendance is only one of

many variables which influence learning. The data give us no reason to doubt

that, it all other variables could be held constant, pupils who attend school

regularly would achieve consistently better than those who do not.

EDUCATIONAL ASPIRATION

The investigation revealed a striking and highly significant

relationship between the educational aspiration of pupils and their school

achievement. The evidence is rather overwhelming that, in general, the higher

achieving

pupils expect to go farther in school than do the low achievers. The evidence

does not reveal which is cause and which is effect, if we assume that a cause

and effect relationship exists. That is, we do not know whether pupils aspire

to continue in school because they learn well or whether they learn well because

their aspiration is high. Perhaps each contributes in some part to the result.

All we know is that high aspiration and high achievement tend to go together.

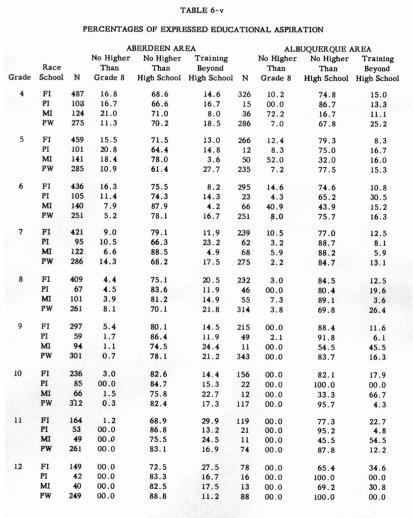

All pupils tested were asked to indicate how far they expected to go in school.

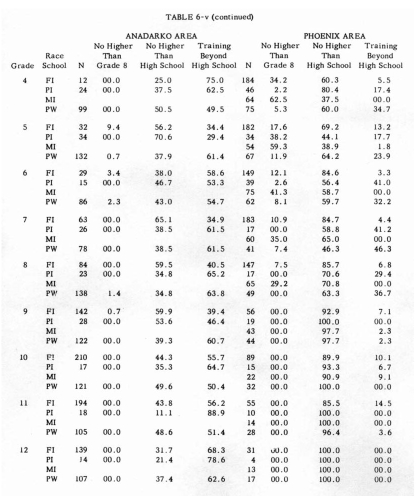

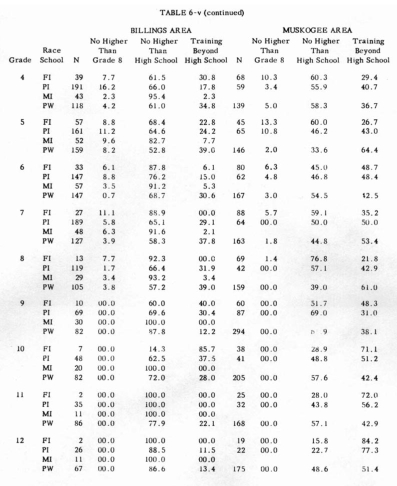

Table 6-v shows the numbers of pupils responding. by areas, grades and race-school

groups. It also shows the percentages of pupils in each of three categories:

1. those expecting to go farther in school than grade eight; 2. those expecting

to go beyond grade eight but no farther than graduation from high school:

3. those expecting to take some kind of training beyond high school. This

latter did not has e to lie college. but could lie nurses’ training or

some sort of trade or business training.

These tables of percentages are shown because it is believed that they will be

of interest to many readers. The great preponderance of even fourth. fifth,

and six-grade pupils, regardless of area or race-school group expected to get

at least sonic high school training. In general, a larger proportion of the pupils

of both races in the Oklahoma areas expected to secure training of some sort

beyond high school than wa5 true for pupils of the other areas.

In most of the areas there is a slight. but not a consistent tendency for a greater

proportion of white pupils than Indian in the elementary and intermediate

grades to aspire to education beyond high school. This proportion is likely to

reverse itself in the eleventh and twelfth-grades, however.

It may be observed that in some of the areas a scattered few pupils who were

in the high school grades indicated that they did not expect to go beyond the

eighth grade, Obviously this resulted from their misunderstanding the question

or inadvertently marking in the wrong space.

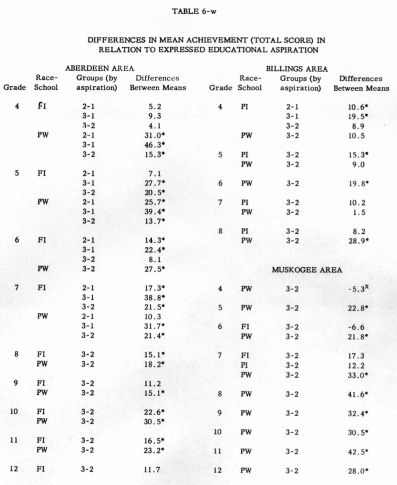

Table 6-w shows comparisons of the average achievement (total score) of the three

groups as defined by level of aspiration. These are shown by areas, grades. and

race-school groups. Comparisons, as usual, were confined to those groups having

thirty or more pupils. In all, eighty-three separate comparisons were possible.

Of these, all but three showed the higher aspiring group to have the higher mean

achievement score. Of these eighty differences favorable to the higher aspiring

groups, fifty-five were statistically significant. Of the three differences favorable

to the lower aspiring groups, none was statistically significant.

It was noted that of thirty-three comparisons involving Indian pupils in Federal

schools, seventeen or slightly more than half were statistically significant.

Of those involving white pupils in public schools, thirty-five of forty-three,

or slightly more than 80 percent were significant. Three of seven differences

involving Indian pupils in public schools were found to be significant. No comparisons

invoking Indian pupils attending mission schools were possible because of insufficient

numbers. There was a tendency for the differences between groups of white pupils

to be larger than was true of Indian pupils.

It is of special interest to note that even at the fourth-grade level the relationship

between educational aspiration and achievement had begun to manifest itself.

1 “The Effect of Pre-School Language on the Educational Achievement

of Indian and White Children in the Southwestern United States” a progress

report submitted by the university of Kansas to the Bureau of Indian Affairs,

January 1954.

2 Shalier Peterson, 1948, “Hos Well Are Indian Children

Educated”: Haskell Institute Press.

3 Kenneth E. Anderson, E. Gordon Collister

and Carl F. Ladd, 1954: “The

Educational

Achievement of Indian Children:” Haskell Institute Press.

4 Statistical Abstract of the United States, Bureau of the

Census, 1950.

5 R. A. Fisher, 1950, “Combining Tests of Significance,” Statistical

Methods for Research Workers, New York: Hafner, pp. 99 – 101.

|