|

HOW WELL ARE INDIAN

CHILDREN EDUCATED?

Chapter Five

RESULTS ON TESTS CONSTRUCTED

FOR THE USIS PROGRAM

Two types of tests were constructed for use

in the Indian Service testing program. In the first group, the

Rural Practices tests

were designed to measure the students' understanding of some

of those things emphasized in the Indian School curricula. It was

recognized that most Indian environments fail to provide certain

types of training which most rural white children are believed

to receive in their home and out-of-school experiences. The Rural

Practices tests include those objectives dealing with the students'

understanding of the uses and conservation of natural resources,

health and safety factors, home economics, and credit. The second

type of test included instruments designed to measure the students'

ability to write correctly. The figures in this chapter describe

the achievement of the students in the various groups and areas

in those fields in which these special examinations were constructed.

In the 1945 program a general resources test was administered

to all of the eighth grade students and regional resources tests

were

given to the boys in three areas. Because of the limited usefulness

of the regional tests, they were not repeated in the 1946 program,

though many of the items were rewritten and utilized in the extension

of the general test.**

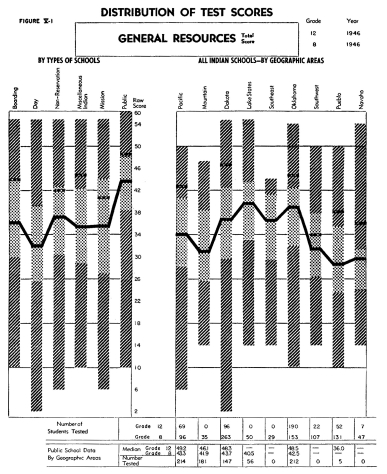

Figure V-1 gives the norms for the eighth and twelfth grade students

on the extended general resources test, which was administered

in 1946. The medians of the various groups and areas vary considerably,

with the public school group at both eighth and twelfth grade

levels demonstrating the greatest competence. The superior performance

of the public school students is interesting and surprising in

view of the nature of the test, which like the other rural practices

tests, was constructed to measure concepts specifically stressed

in the Indian school curriculum. It was thought that the Indian

students in public schools would constitute something of a control

group in measuring the degree of effectiveness of the instruction

in resources given in the Federal schools. Although the Indian

students in public schools at both the eighth and twelfth grade

levels did less

well than white children, they demonstrated higher competence

than the students in any of the Indian schools. This would indicate

that the formal instruction given in the Indian schools does

not equal in effectiveness the training in general resources

which is gained through informal channels by students attending

the public schools. In other words, results indicate that the

training in resources provided by Indian Schools is not sufficient

to compensate for the lack of out of school experiences.

It was thought that this trend, as indicated in the 1945 battery,

might be partly explained by the fact that the items included in

this examination were those which were of such a general nature

that they were labeled as suitable for Indian students in all of

the areas. Such criterion of selection would naturally produce

a test that would include a wide sampling of items, most of which

would be relatively easy. If this sample of items were fairly easy,

it would be highly probable that most of these same facts and principles

had been discussed and described in story books, science magazines,

story magazines, magazine advertisements and newspapers, thereby

giving any student who did a fair amount of reading as good a chance

for knowing these items as the student who had experienced these

facts first-hand on the farm. Therefore, it was thought possible

that the test, as developed in 1945, might not have been discriminating

between actual firsthand training and experience and the kind of

information that could be gained by reading magazines and newspapers.

It was for this reason that the 1945 general resources test was

extended, making it three times as long as the original test. When

it was observed that the data from the 1946 program revealed the

same trends, it was concluded that the construction of the original

test and the seeming simplicity of some of the items probably could

not account for the better performance of the public school students.

In other words, the differences indicated are probably due to a

failure on the part of the Indian Schools, despite their recognition

of the problem, to provide instruction that will as yet offset

or balance that training which the public school student receives

in his out-of-school experiences.

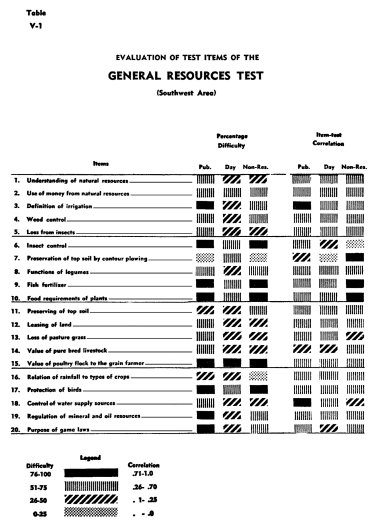

Tables V-1 and V-2 graphically present data on the relative difficulty

and discriminating value at the eighth grade level on each of the

twenty items of the 1945 General Resources Test. These twenty items

are identical with the first items in the 1946 test. Table V-1

presents the data for the Southwest Area and Table V-2 for the

Dakota Area. These two areas were selected for comparison because

they constitute relatively large groups, each having recognized

differences. Also, at the eighth grade level, each of the two areas

includes a fairly good representation of the different types of

schools, although for this comparison, data from only the public,

day and non-reservation schools have been used.

Per cent of Correct Responses means the per cent of students answering

any particular item correctly. For example, in item number 3, which

calls for a definition of irrigation, more than 3/a of the public

school students answered it correctly, while between 1/4 and %2

of the day school students and %2 to 3/a of the non-reservation

students were able to answer it. In this particular item there

is a difference between the achievement as demonstrated by the

students in the three different types of schools. Table V-2 shows

that the item has about the same difficulty in the Dakota area

as in the Southwest for both the public and non-reservation students,

but the day school students in the Dakota area found the item easier

than did the day school students in the Southwest. In instances

such as item number 15, on the value of the poultry flock to the

grain former, the item was extremely easy for the students in all

three types of schools and in both areas. This type of information

relative to individual items allows the instructor and the supervisor

to tell something about the specific items and objectives that

are apparently being taught more effectively in one type of school

or in one area than in another.

In general, it may be concluded that while some specific items

show considerable variability in difficulty from school to school

and area to area, there are a great many items that are mastered

about equally well in the various types of schools and in the different

areas. While the public school students in the Southwest do equally

as well or better than the other two groups, there are only two

items-numbers 7 and 11-in which Indian training seems to have resulted

in superior performance. Items numbered 2, 7, 14 and 19 in the

Dakota area show the Indian students doing better than the public

school students.

The discriminating value or item-test correlation provides an index

as to relative usefulness of the item in selecting the students

who have performed very well I on the test as a whole from those

who have not done so well. In this particular instance, these data

were computed by comparing the performance on the basis of this

particular test, of the students in the top half of the class,

with those in the bottom half of the class. Items such as those

numbered 3 and 18 have item-test correlation values of better than

.70, which means that there is a very high correlation between

the public school student's performance on these items alone and

what he is able to do on the test as a whole. It is interesting

to note that items that are discriminating for public school students

are relatively discriminating for the Indian school students as

well. In other words, items that will select able students in one

type of school are nearly as useful in other types of schools for

selecting the good students from the poor ones. It is also gratifying

to note that a relatively high percentage of the items have discriminating

values of better than .25, for some test builders employ this

figure,

including as good items those having higher values than .25.

There are relatively few instances in which a zero or negative

relationship is exhibited. A zero relationship might indicate

that the material had not been taught and a negative correlation

might indicate that the instruction concerning the item was contrary

to the response considered correct by those who constructed the

test. Of course, zero or negative correlations may also be interpreted

as indicative of weaknesses in the item, or in the way that it

has been stated, but in view of the fact that all of these items

have merit in most schools and areas, the negative correlations

probably do not reflect weaknesses in the test item itself. Item

16 from the Dakota area is a case in point. The item is very

discriminating for the public school students and somewhat so

for the non-reservation school students, but for the day school

students it may point to the fact that this item is not taught

or that a certain amount of misinformation may have confused

the students.

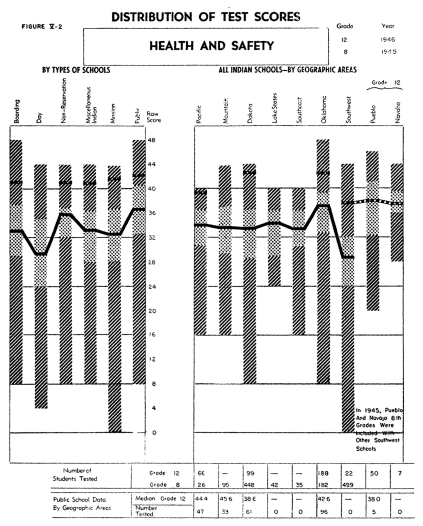

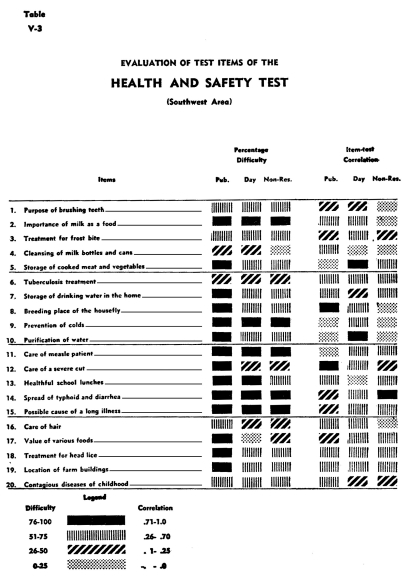

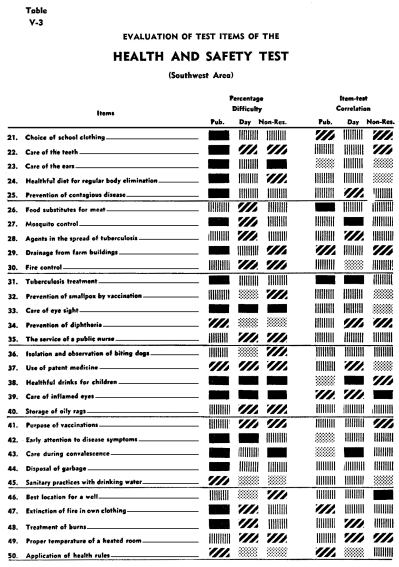

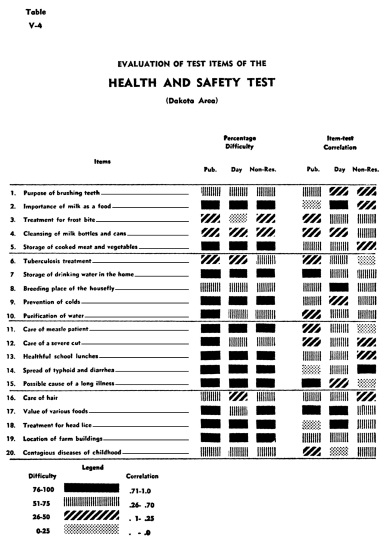

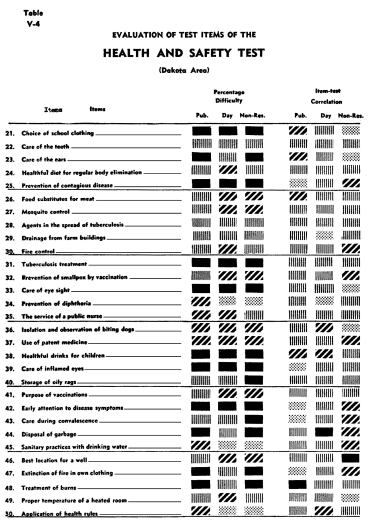

Figure V-2 is the norm sheet for the Health and Safety Test. Tables

V-3 and V-4 describe the content of all fifty items as well as

showing the relative difficulty of the various items and their

degrees of discrimination.

Figure V-2 reflects tremendously wide ranges of performance between

the students in each of the groups but in most instances the differences

between the medians of the groups are not large enough to be important.

Though the students in the day schools demonstrate the poorest

performance at the eighth grade level, there is almost no difference

between the students in the various types of schools at the twelfth

grade level. . In the Dakota region the twelfth grade students

in Indian schools did a little better than the students in public

schools, and in Oklahoma, students in the two types of schools

did equally well. The results would indicate that health and safety

instruction in the Indian schools has been sufficiently effective

to compensate for the students' lack of home training.

This test furnishes a good example of the usefulness of item-by-item

analysis of the test data. The instructor will find much of interest

to him in Tables V-3 and V-4, for these tables reveal the specific

topics in which the eighth grade students from the three types

of schools of the Southwest and Dakota areas encountered varying

degrees of difficulty. For example, item 10 measures the students'

understanding of the health and safety factors contributed by the "purification

of water." In the Southwest it will be noted that the item

was very easy for the public school students, having been answered

correctly by more than three-fourths of them. In the day and non-reservation

schools, the students found this same item somewhat more difficult.

The symbols in the right hand columns describe the discrimination

values of the items. Among day school students, item 10 was highly

discriminating, for it was easy for the good students and difficult

for the poor students.

In the cases of both the public school and non-reservation students,

the item is shown to possess negative or zero discriminating

value. For the public school students, this lack of discrimination

should modify the interpretation that has probably already been

given by those who have observed that the public school students

are well informed on the item of water purification. While it

is still true that they are relatively well informed, it is also

of importance to know that the poorest students in this group

do just about as well as the best students in the class. When

an item has been thoroughly and effectively taught to a class,

it is often found that both the poor and good students, as measured

on the test, show near perfect performance on the item. On the

other hand, the fact that good and poor students do equally well

could also mean that this item was not taught in school but that

the students have acquired the information elsewhere. For the

non-reservation students in the Southwest item 10, on water purification,

appears to be relatively easy, but is not discriminating. One

would conclude, therefore, that in this area, the understanding

of water purification among non-reservation students is not a

good index as to whether they understand all of those factors

which have been included in this test on health and safety. Specific

teaching of the water purification topic should have the effect

of increasing the discriminative value of this item the next

time such a test is given, for the better students will in all

probability have their scores improved much more than will the

slower or poorer students. The discriminating value of item 10

has not been computed for the twelfth grade data. It is possible

that the teaching in the four-year period between eighth and

twelfth grades will be found to have produced a higher discriminating

value for the item on the twelfth grade tests.

The non-reservation students in the Dakota area find item 10 about

as easy as do the students in the Southwest, but in the Dakota

area, the item is highly discriminating. This could be interpreted

that there has been a more definite effort to teach water purification

to the non-reservation students in the Dakota area than to the

students in the Southwest.

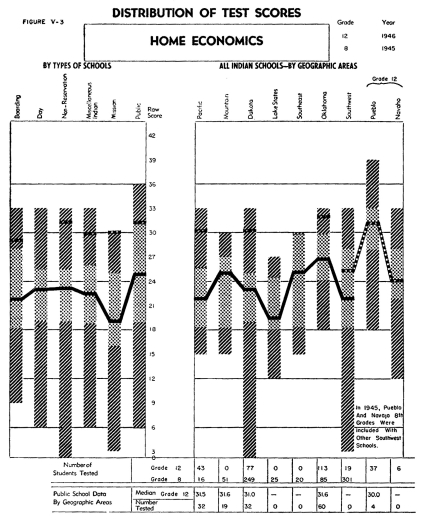

Figure V-3 shows the distribution of test scores for the Home Economics

Test. This test was designed as a companion for the General Resources

Test and was given to all of the eighth and twelfth grade girls.

No regional tests were prepared because the subject matter included

was judged to be of importance to the girls in all areas. The performance

of the girls on the Home Economics Test is about the same for all

types of schools with the exception of the eighth grade girls in

mission schools who fall somewhat lower. The performance of the

Oklahoma Indian school group, at both the eighth and twelfth grade

levels, is higher than that of the total public school group

at comparable

grade levels. This is of special interest when one

considers that the test was prepared to measure the degree to

which the Indian Schools have been successful in their attempt

to compensate for the lack of home training which their students

receive in relation to good homemaking practices. The fact that

this performance is due to instruction in Indian schools is pointed

to by the fact that the public school Indian students do less

well than the non-Indian students.

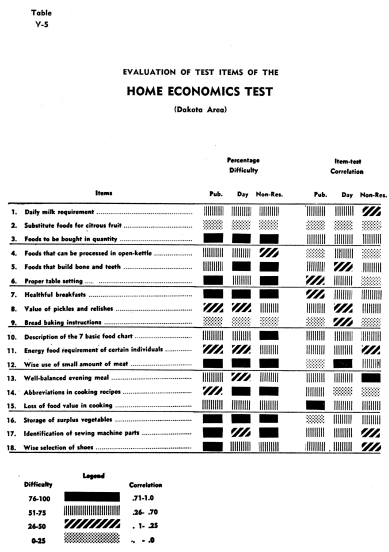

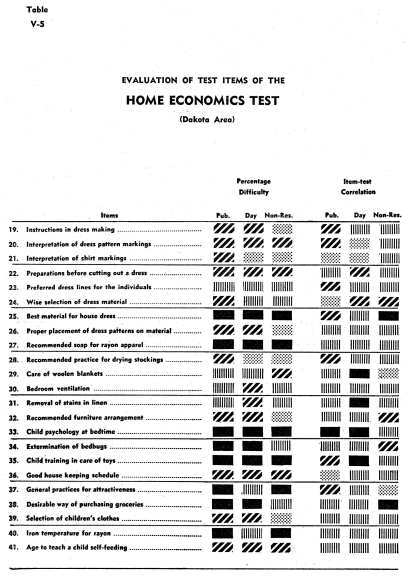

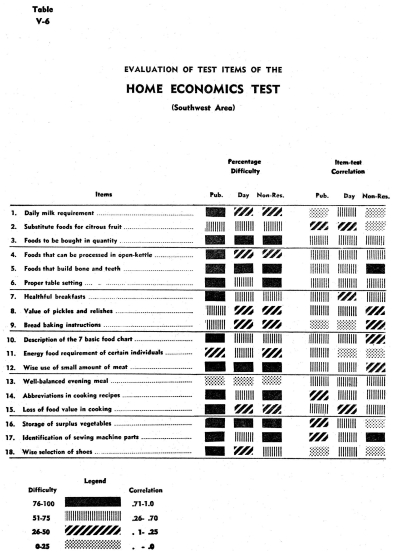

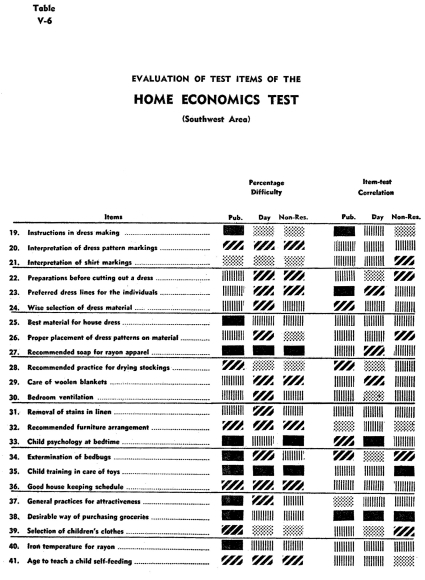

Tables V-5 and V-6 present an evaluation of the items in the Home

Economics Test. As in the previous item evaluation, these data

have been computed for the Dakota and Southwest areas. Examination

of these figures will disclose much more agreement than might be

expected. The few items, such as numbers 2, 9, 21 and 28, that

are very difficult for all the students seem to be difficult for

the students of both areas and for the students in all three of

the types of schools. Therefore, if this difficulty is due to the

material not being taught or being taught incorrectly, the fault

is not characteristic of a single type of school or of the schools

in either of these areas. The same thing may be said for the items

which appear to have been easy, such as numbers 3, 5, 7, 12, 14,

16, 25, 27, 33, 35, and 38. All of these items appear to be fairly

easy for students in all three types of schools and in both areas,

again showing no appreciable deviations.

The curriculum expert would probably look for more instances such

as items numbered 18, 26, and 37 in the Southwest, for here in

Table V-6 are examples of the three types of schools in this area

demonstrating three levels of proficiency. While these three items

will undoubtedly be of passing interest, the fact that only three

items have such ranges is hardly enough to make anyone think that

there are significant differences in the attention given to Home

Economics. On the whole, the discriminating values for the Indian

School groups are higher than for the public school students, and

this is additional evidence that the test measures achievement

of topics stressed in the Indian School curriculum.

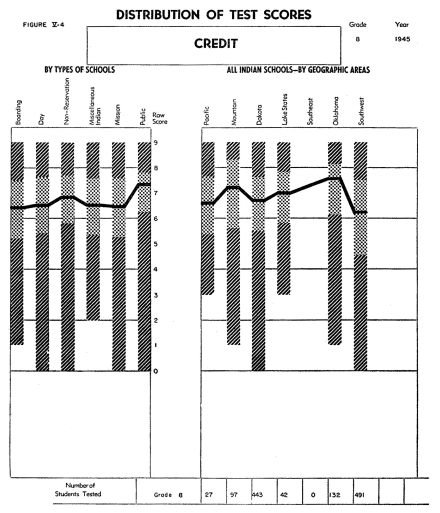

Figure V-4 is a norm sheet describing the achievement of students

on a test which has been called the Credit Test. The purpose of

this examination was to determine the kinds of conditions or situations

which the students felt would justify the granting of credit or

loans. Various situations were described in each item of the examination

and in each case the student was expected to decide whether or

not the situation was such as to warrant the giving of credit.

The situations were so set up and described as to convince those

responsible for the test that the situations were typical and that

all of the items could be keyed. The situations chosen were those

which students might have observed and which due to their own training,

lack of training, or prejudice might answer incorrectly. The results

from a test of this sort therefore reflect a great many things.

Certainly it would not be wise to

interpret the results as a measure purely of educational opportunity

or direct training in the classroom, for the training, whatever

it might be, is modified so much by home experiences. Therefore,

it is possible to think of this test partly as one measuring

attitudes and its results should be examined diagnostically with

that in mind.

Figure V-4 illustrates that there is relatively little variability

between the median attainment of the different types of schools,

but somewhat more variability between the Indian schools in the

different regions. In this test the Oklahoma group is highest,

even higher than the median for all public schools. Analysis of

the test items showed that none of the items gave negative correlation

values. In fact, most of the correlation values were relatively

high, showing a high degree of discrimination. However, the credit

test was not repeated in 1946 for it was planned to incorporate

these, or modified items, in a longer test designed to measure

a wide scope of attitudes. This test is still under construction.

A Rural Practices Vocabulary Test was constructed for administration

in the 1946 program. Its purpose was not that of a general vocabulary

test, but rather that of measuring the degree to which the students

understood the vocabulary being used in the rural practices tests.

The purpose of the test has been fulfilled when it has been discovered

that:

1) the achievement of all students on this select vocabulary is

relatively high, thereby indicating that the word difficulty of

the rural practices tests was not a serious handicap;

2) a positive correlation between the vocabulary -and rural practices

scores exists; and

3) the results have been made available to the teacher in order

that the scores on the special vocabulary may be used in the analysis

of individual student scores on the rural practices tests.

The second type of tests constructed for use in this study are

known as the Free Writing Tests. It was decided that the standardized "proof

reading" type of English test was inadequate to measure the

students' skill in written expression. The standardized test measures

the students' ability to detect errors in printed material; the

Free Writing Tests measure the students' ability to use English

in expressing his own thoughts clearly and correctly.

In 1945 two forms of the Free Writing Tests were given to each

of the eighth grade students. Because Form A of the test appeared

to motivate a freer type of expression, this form of the test was

given in 1946 to all of the fourth and twelfth grade students.

Unfortunately, the extent to which the method of interpretation

of results would be altered was not anticipated in time to indicate

the desirability of repeating the test at the eighth grade level.

Objective scoring of the Free Writing Tests is somewhat more difficult

than the scoring of most standardized tests, but the results

indicate that it is a better measure of the type of language

skill which Indian schools are attempting to develop. Each of

the 1946 papers was scored in three ways to determine:

1) the total number of errors in spelling, punctuation, usage and

sentence structure,

2) the maturity of English construction attempted, and

3) the types of errors most common at different grade levels and

in different geographic areas.

A fourth type of analysis which is recognized as important, but

which has not been undertaken thus far, is a qualitative analysis

of the ideas expressed-the abiIity of the writer to sustain the

reader's interest, his imagination and creativeness.

Figure V-5 shows the results or norms for the Free Writing Tests-Total

Errors Per Sixty Words for the fourth and twelfth grade students

in 1946. The distribution of scores on the 1945 study are not shown

because the revision in method of analysis yielded scores which

are not comparable to those reported in 1945. The unit of sixty

words in each composition was decided upon because the opportunity

for error increases in proportion to the length of the composition.

Experimentation indicated that there is considerable consistency

in the number of errors which occur throughout the composition.

A correlation of .872 was found between the error score based upon

sixty words of a composition and the error score of the entire

composition. It was therefore decided that sixty words was a sufficiently

reliable sample of the whole.

The opportunity for error likewise increased in proportion to the

increase in complexity of the composition. For example, a student

may entirely eliminate errors in either omission or wrong use of

commas by using only simple sentences where periods are adequate.

There are fewer opportunities for errors in sentence structure

if he uses short, choppy sentences.

The following fourth grade compositions serve to illustrate the

importance of considering complexity as well as the total number

of errors in making comparisons between the achievement in the

Free Writing skill of different students.

(Example)

The man is riding on a horse. A dog is going with him.

The man is going to the hills. A girl is standing by the door.

She is telling

him to be back before sundown. There is a little house a little

way from the house. The dog stays in the little house.

There are trees… Hemill

bring a rabbit.

In contrast to the simplicity of this paper, the following sample

illustrates the opportunities for error, and resultant errors which

occurred through the introduction of complex and compound sentences.

(The 60 word sample in heavy face type indicates the 60 word sample

which was used as a basis of computing the total error score.)

(Example)

This Indian is going out toward the mountains to kill large game

for his family, and he is taking one of his best dogs with him.

He is going out because his family do not have anything to eat

in their house for supper.

He is the only Indian warrior in the camp, because just his family

and him are the only ones there.

The little girl at the door is trying to tell him to bring back

a live baby deer for her pet.

After he's gone a little way She tells him Goodbye and then go

back into their little house.

The mountains are high and rocky but the Indian is going out to

hunt. The Indian man will return soon, from his long hunt in the

mountains. The Indian man told the little girl that he would kill

a deer and bring back two baby deer for the little Indian girl's

pet. The little girl is so happy that she claps her hand and tells

him to take care of himself on the journey.

After along time the little girl wonders why her father hasn't

returned yet. But her questioned is soon answered, for out in the

open spaces comes some Kiwoa Indians to the camp to get the women

and children and make slaves out of then and take them home to

their houses.

But that was not all because the little girl saw out in the opening

saw her father coming across the broard plan with something on

the pony's back and two baby wolfs in his arms instead of deer.

When the Kiowa Indians saw him coming they ran off and were never

seen again because the man had brought back other warriors who

were part of the people. There were about 49 people who were with

them then. and then they lived happily together and when the wolf

got big she littered.

Since many errors in punctuation result frorn wrong use, it was

decided to show the opportunity for errors in punctuation by counting

the number of different kinds of punctuation marks which the student

attempted to use. Only those which were used in the 60 word sample

were considered in determining the qualitative punctuation score.

The number of different words of more than one syllable was used

as an index of the student's attempt to use complex words. Obviously

a student with limited spelling ability might make relatively few

errors if he used only simple words which were easy to spell. Since

a misspelled word was counted an error only once, the use of an

index which indicated different words was suggested since repetition

of the same word decreased the opportunity for spelling errors.

The third type of analysis of the Free Writing papers involved

a careful study of the specific types of errors found in the papers

of the different Indian students. This study was made by means

of careful sampling of the papers of both fourth and twelfth grade

students in each of the geographic areas. The samples were grouped

so that the findings indicated whether an error was typical of

all students at this grade level, or only of those who made many

errors.

It was found that there was marked similarity, both in type and in frequency

of errors, between the poorest twelfth grade and the best fourth grade papers:

With the exception of errors in the use of the comma, the frequency of each

type of error was considerably higher among the fourth grade students. In the

case of the comma errors, it seems probable that the opportunity for comma

errors was markedly increased by the greater complexity of the twelfth grade

compositions, for the twelfth grade students made more errors in the use of

the comma than did the fourth grade students. The largest percentage of errors

among all fourth grade papers were those of omission of capital letters at

the beginning of sentences. Almost as many errors at the fourth grade level

were in the capitalization of common nouns and the use of a capital letter

at the beginning of each line: The total number of errors in the wrong use

of the capital letter was greater than those resulting from omission of capital

letters. This difficulty in the use of capital letters in the fourth grade

may spring from the fact that most Indian Schools do not place as much emphasis

on the proper use of capital letters in the lower grades as is customary in

the average public school. This omission is deliberate, and designed to simplify

the problem of alphabet recognition for pupils coming from nonreading homes.

The most frequent errors in sentence structure were classified as "awkward

and dangling sentences and modifiers." Among the poorer twelfth grade,

and most of the fourth grade papers, the "run-on sentence" accounted

for a large percentage of errors. The verb error which occurred with greatest

frequency at both grade levels was in lack of agreement with the subject in

person or number. At the fourth grade level the omission of the verb or auxiliary

and the omission of an "ing" ending was common. The most frequent

noun errors were those which resulted from a confusion of plural and singular

forms. A relatively large percentage of errors resulted from mistaken identity

of words. It is interesting to note that almost no double negative errors occurred

at either grade level.

It was noted by those who scored the 1945 Free Writing tests that the illegibility

of the penmanship sometimes made it difficult to determine whether or not the

student had misspelled a word. It was decided that the quality of student penmanship

should be studied in 1946.

Because it has been suggested that there is no merit in forcing a child to

transfer from manuscript to cursive writing, students in many of the Indian

schools continue to use manuscript writing throughout their entire period of

school attendance. It was therefore necessary to employ two separate Handwriting

Scales?one for judging the quality of cursive writing and one for manuscript

writing.

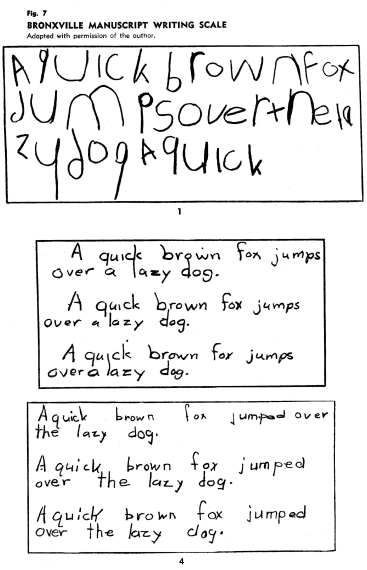

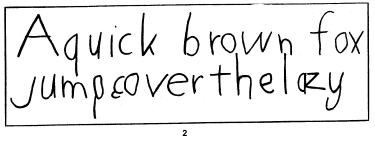

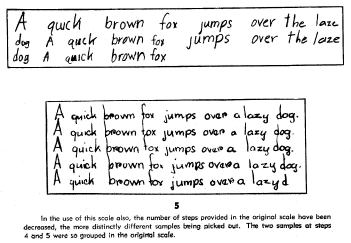

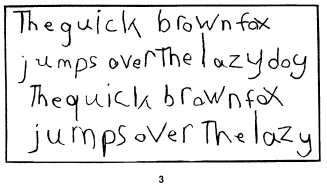

A large number of scales were examined for their possible usefulness in evaluating

the quality of handwriting. It was necessary that the range of the scale should

be wide in order that it would extend from the poorest penmanship of the fourth

grade students to the best penmanship of the twelfth grade students. All of

the scales examined appeared to discriminate between finer differences in quality

than seemed either justifiable or necessary. An attempt was made not to require

the distinction between extremely small differences so that there would be

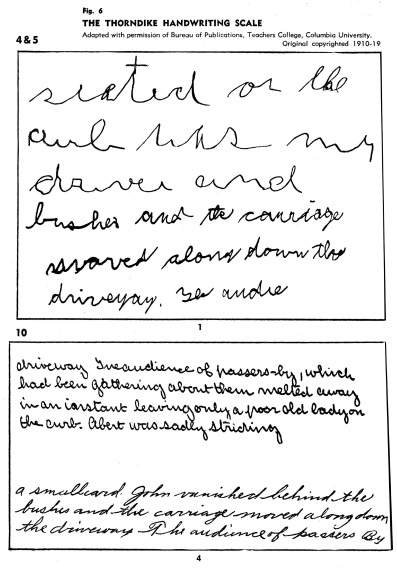

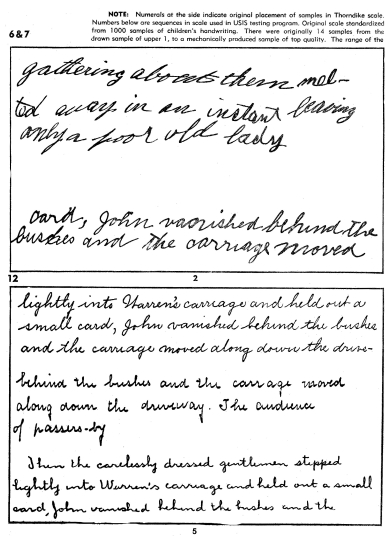

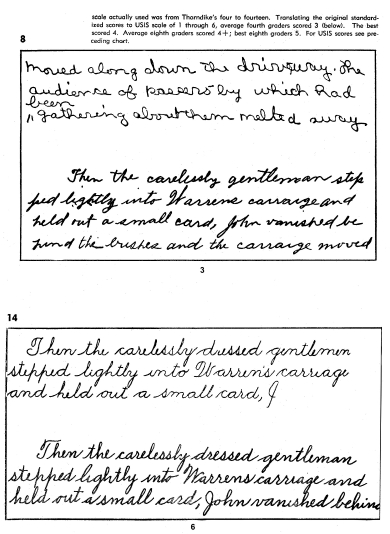

no disagreement between the judges. Cursive writing was evaluated by comparison

with samples selected from the Thorndike Handwriting Scale, shown in Figure

V-6. The samples from the Bronxville Scale of Manuscript Writing, by which

the quality of the manuscript penmanship was judged, are shown in Figure V-7.

Three classroom teachers were selected to rate the penmanship of all students

who took the Free Writing tests. In order to evaluate this method of scoring

penmanship, one hundred samples of twelfth grade penmanship were compared with

the selected samples by each of the three judges. The rating of each judge

was so indicated that his rating could not be seen by the next judge. The independent

ratings of the three judges were then compared. It was found that in no instance

did all three judges disagree as to the quality of the penmanship and, in no

instance did the judge who disagreed with the other two deviate more than one

point on the selected scale. In seventeen instances, one of the three judges

disagreed with the other two. In 83 instances there was unanimous agreement.

The method was repeated with 100 samples of the writing of fourth grade students,

again with 100 samples of students of different grade levels, and again with

students who used manuscript writing. The results each time were almost identical.

The disagreements never exceeded that of the first experiment and there were

never less than fifteen disagreements.

It was found that some of the disagreement resulted from difference

in opinions of the judges in regard to the merit or lack of merit

of flourishes, and "Spencerian type" of

writing which did not fit on the scales selected. The primary grade

teacher was somewhat more sensitive to "drawn" writing

than were the secondary teachers. Recording first impressions appeared

to result in at least as high reliability as careful analysis of

the sample.

The rating assigned to the penmanship represents the independent

agreement of at least two of the three judges. It is of interest

to note that the time required to obtain three independent judgments

of approximately. 4,000 papers, including the recording of the

ratings, was 10 days, or 240 man-hours.

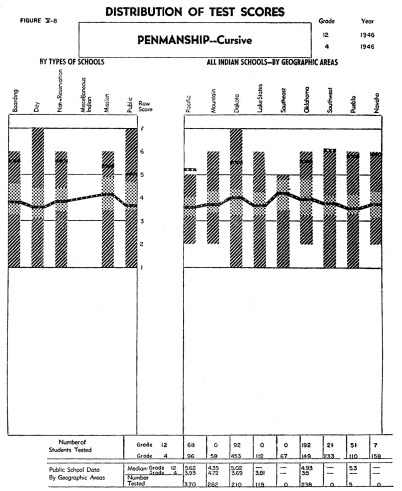

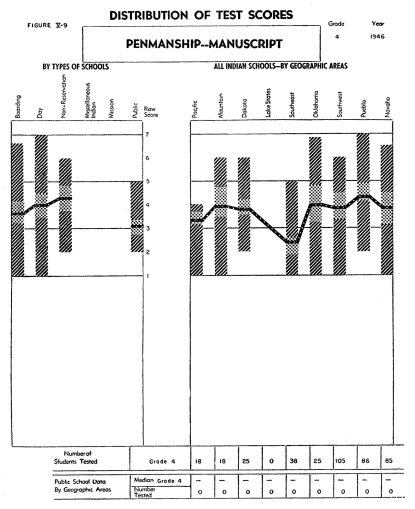

Norms for the quality of penmanship of the fourth and twelfth grade

students are shown by Figures V-8 and V-9. The number of students

at the twelfth grade level who elected to use manuscript penmanship

was too small to permit computation of norms for that grade.

** See Appendix A for details of the revision

of the test

|