|

Reforming Education From the Inside-Out:

A

Study of Community Engagement and Educational Reform in Rural Alaska

James W. Kushman

Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory

Ray Barnhardt

University of Alaska Fairbanks

Contact Person:

Jim Kushman

Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory

101 SW Main Street, Suite 500

Portland, OR 97204

Phone: 503-275-9569

Fax: 503-275-9621

Email: kushmanj@nwrel.org

Published in Journal of Reaearch in Rural Education, Fall, 2001

Abstract

This paper presents a study of rural educational reforms

that were designed to increase community engagement and parent involvement

in education.

The

reform effort was called Alaska Onward to Excellence and took place in

small, isolated

rural communities spanning western, central, and southeast Alaska. Case

studies of seven of these communities examined how school-community partnerships

are formed and sustained so that educational reform can become a more

stable

endeavor

that ultimately benefits all students. A cross-case analysis, conducted

by research teams including university and regional laboratory researchers,

school practitioners, and community members, resulted in four key findings.

First,

reform efforts in small communities require an inside-out approach that

starts

with existing community relationships, builds trust across groups, and

designs reforms around local place, language, and culture. Second, parent involvement

requires a deeper understanding of new parent roles by both parents and

teachers,

and strong proactive efforts to engage parents rather than simply invite

parents to participate in the school’s agenda. A third essential

ingredient for successful partnerships is moving from top-down to shared

leadership so that

the ownership and commitment for school change is embedded in the community

rather than with school personnel who constantly come and go. Finally,

educational improvement and community health are overlapping goals in

small communities;

schools need to focus not only on academic standards, but also integrate

strong cultural standards for Indigenous people, along with character

goals and life

skills that can lead to making a life as well as a living. Case study excerpts

are included to provide concrete examples of the key findings, and generalizations

are drawn to illustrate how these results apply outside of Alaska.

Reforming

Education From the Inside-Out in Rural Alaska:

A Study of Community Engagement and Systemic Reform

Bonds among people,

and between people and place, run deep in small rural communities.

In rural Alaska,

these bonds are intensified by dynamic cultural, climatic and geographic

features that can make life both rewarding and challenging at the same

time. Especially

strong bonds are forged through the cultural heritage of the Native

people for whom rural Alaska is home, and who view their world as a unity of

the human, spiritual, and natural realms (Kawagley, 1995). People

in

rural

Alaska certainly

experience their share of human conflict, but survival is sometimes

a matter of coming together to achieve a higher purpose or goal.

In stark contrast

to the strong human bonds and sense of place that can hold a small community

together, formal education in rural Alaska

has

often been

characterized more by conflict than cohesion. The formal education

system in rural Alaska is still very young, but its short history

is marked

by persistent cultural and political differences between Indigenous

people and the educational

institutions serving them (Barnhardt & Kawagley, 1998). This

study examines how two related reform mechanisms—community

engagement and parent involvement—are

being used in rural Alaska to change this historical pattern and

achieve a more unified educational system The dynamics of community

engagement

and parent

involvement are examined, including the factors that help and hinder

school-community partnerships, and the changes that result when school

and community work together.

While rural Alaska is in many ways a unique place, there are lessons

from this study that can be applied to rural schools anywhere, particularly

those serving

Indigenous people.

Engaging the Community in Systemic Reform

Community engagement

and parent involvement hold promise as ways to improve and revitalize education

at a time when the public’s confidence in public

schools is dwindling. Community engagement can be characterized

as a quiet revolution occurring in large and small communities across the

country that

works towards inclusiveness, stronger consensus around educational

goals, and real change in educational practice and outcomes. Community engagement

does

not necessarily lead to quick results. Instead it represents

a long-term investment in building ownership, capacity, and “social

capital” for

deeper changes in educational policy and practice. (Annenberg Institute for

School

Reform, 1998). In poor rural areas, community engagement is especially

important because public schools are often the most visible and accessible

institutions

for bringing people together around community concerns. In many

rural communities there is a strong sense of local place and an essential

connection between

education, economic vitality, and community health. Community

engagement can be a powerful force for social and educational integration

in small rural

communities.

Parent or family involvement is a related reform theme that

speaks directly to partnerships between schools and parents (or other

caregivers) for

the purpose of strengthening the links between parental expectations,

student

motivation,

learning habits, and academic performance. Joyce Epstein (1991,1995;

Epstein & Hollifield,

1996) and other researchers (Griffith 1996, Henderson & Berla,

1994, Thorkildsen, Thorkildsen & Stein, 1998) provide evidence

that parent involvement in the educational process reaps positive

results for students, teachers, and

parents. School-family partnerships are especially beneficial

in leveling the effects of poverty by helping parents, teachers,

and students in impoverished

communities develop coordinated strategies that lead to high

expectations for educational attainment as well as constructive

learning habits. Successful

partnerships can transcend the effects of poverty and social

class by capitalizing on a strong sense of caring for children

shared by parents and teachers even

in the most impoverished communities. Successful partnerships

require a strong and sustained effort on everyone’s part

(Epstein, 1995). This is particularly true in communities where

parents have felt disenfranchised because of race,

culture, or poverty. Successful partnerships not only depend

on how welcome parents are made to feel by the school, but

on parental beliefs about their

role in the educational process. Parent role conceptions are

influenced by many factors including social and church groups,

race, social class, and basic

beliefs about child development and child-rearing. Parent expectations

about their involvement also depend on their own sense of efficacy.

Parents with

low educational attainment, for example, often see a very limited

role for themselves in helping their own children succeed in

school (Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler,

1997).

The communities participating in this study had agreed

to participate in a district-led reform process called Alaska

Onward to Excellence

(AOTE), one

of several school reform efforts initiated in Alaska in recent

years. AOTE

was a strategic planning process that involved districts and

local schools working closely with their communities to develop

a vision

and goals,

write improvement plans, and implement new practices with a

focus on partnership

activities that bring the school, home, and community together.

At the same time, two other related reforms were occurring

in these schools and communities.

The Alaska Quality Schools Initiative was picking up steam

as a state-driven

reform effort stressing high learning standards, assessment

benchmarks, improving the quality of teachers, and school-family

partnerships.

A

third reform initiative—the

Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative (AKRSI) in concert with the

Alaska Rural Challenge—was

aimed at integrating the formal education system and the Indigenous

knowledge systems across rural Alaska communities through the

implementation of a set

of Alaska Standards for Culturally Responsive Schools. AKRSI

has worked to develop the curricular and instructional tools

allowing Alaska Native communities

to fully integrate (rather than merely add on) local knowledge,

language, and culture into formal education.

Reforms that Address

Chaos and Complexity in Rural Alaska

These new reforms are

the most recent attempts to improve the formal education system in rural

Alaska, a system that is still

at the

adolescent stage

of development. Building on early 20th century missionary

schools, a dual system

of public

education eventually emerged by the early 1960s in the form

of federal Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and state-operated

schools.

As the

1970s unfolded,

a continuing record of inadequate performance by the BIA

and state-run schools, coupled with the ascendant economic and

political power

of Alaska Natives,

led to the dissolution of the centralized systems and the

establishment of 21 locally controlled regional school districts serving

rural communities. Native communities obtained political

control of

their elementary schools

for the first time, while concurrently a new system of secondary

schools was emerging.

A class-action lawsuit brought against the State of Alaska

on behalf of rural

Alaska Native secondary students led, in 1976, to the creation

of 126 village high schools to serve rural communities where

before, high

school students

had to leave home to attend boarding schools.

A constantly

shifting array of legislative and regulatory policies impacting rural schools

makes it clear that the

education system

in Alaska is still

evolving and is far from a state of equilibrium. This is

especially true in rural Alaska,

where the chronic disparities in academic performance,

ongoing dissonance between school and community, and yearly turnover

of professional

personnel place the

educational system in a constant state of uncertainty and

reconstruction. Rural schools still struggle to form an

identity as they try

to relate to the needs

of their communities. Reform often becomes a never-ending

cycle of buzzword solutions to complex problems. Within

the last

decade alone,

rural education

in one corner of the state or another has been subjected

to variations of mastery learning, Madeline Hunter techniques,

outcome-based

education, total

quality

learning, site-based management, strategic planning, and

many

other imported quick fixes to long-standing endemic problems,

right up

to the current

emphasis on high standards. The short-term life span of

these well-intentioned but

ill-fated reforms has only added more confusion to a system

that is already teetering

on the edge of chaos.

From a systemic perspective, there

are some advantages to working with systems that are operating “at

the edge of chaos,” in that they are, paradoxically,

more receptive to change as they seek some form of equilibrium

(Waldrop, 1994). Such is the case for many school systems in rural Alaska,

and thus gaining

an understanding of the complexity and dynamics of systemic

reform was a major focus of this study.

Research Questions

Are community engagement and parent involvement

appropriate routes to systemic reform or just another “flash

in the pan” for rural Alaska? This

was a central issue in the seven case studies on which

this report is based. More specifically, this research addressed

the following core questions:

- How can schools and communities successfully work together to achieve

common goals for rural Alaska Native students?

- What are the essential elements of this partnership and how is it

sustained over time?

- What factors promote the partnership and what barriers stand in

the way?

- What lessons can we learn from these case studies to guide future

improvement efforts in rural Alaska or other similar communities

across the country?

Seven Case Studies of Systemic Reform

The

seven communities studied span western, central, and southeast Alaska and

range in size from approximately

125

to 750 residents.

Most of the

communities were nearly 100% Alaska Native (primarily

Yup’ik but also other groups

including Athabascan and Tlingit Indians) or at least

mixed-communities with significant Alaska Native

heritage. The seven communities studied are listed

below.

- Quinhagak in the Lower Kuskokwim School District, on the Kuskokwim

Bay

- New Stuyahok in the Southwest Region School District, northeast

of Bristol Bay and Dillingham.

- Tuluksak in the Yupiit School District, northeast of Bethel on the

Kuskokwim River

- Aniak and Kalskag (treated as a single case study of neighboring

villages) in the Kuspuk School District, northeast of

Bethel on the Kuskokwim River

- Koyukuk in the Yukon-Koyukuk School District, west of Fairbanks

at the confluence of the Koyukuk and Yukon Rivers

- Tatitlek in the Chugach School District, on Prince William Sound

near Valdez

- Klawock, a single-site school district (Klawock City Schools) on

Prince of Wales Island, far southeastern Alaska near Ketchikan

These communities are

all remote villages or towns reached by small airplane. Their schools, which

can serve as

few as 20 or

as many

as 200 students

in grades K–12, come under the supervision

of separate school districts in a system of Regional

Educational Attendance Areas. In rural village

schools, students

are typically educated in relatively modern school

buildings (including a library and a gymnasium)

and often in multigrade classrooms. Instruction

in the early

years may be in a Native language (such as Yup’ik)

and most schools today try to incorporate at

least some Alaska Native cultural components

into the

curriculum. While most teachers come from outside

the state or region, community members often

serve as classroom and bilingual aides (Barnhardt,

1994).

Alaska Onward to Excellence

While the seven sites

were diverse in their make-up and histories of local school reform, what

they shared in

common was a

district-initiated reform

process called Alaska Onward to Excellence

(AOTE). In AOTE, school districts and village

schools worked closely with community stakeholders

(parents, elders, other community members,

and students) to establish

a district

mission statement

and related student learning goals. Working

through multi-stakeholder leadership teams, AOTE attempted

to develop a long-term

school-community partnership

and action plans to achieve community-valued

learning goals. In AOTE, the educational

partnership is achieved through a number

of mechanisms: a series of

school-community meetings to develop a vision,

mission, and set of community-valued learning

goals that everyone commits to; involvement

of parents, elders, community members, and students

on district

and village leadership

teams that

guide a multi-year

improvement process; development of new educational

strategies that stress parents, elders, and

other community members

as partners with

the school

in education; and creation of a long-term

covenant that assigns equal responsibility for student

success to school

personnel

and the community.

This educational

partnership was the focal point of our case

studies.

As discussed earlier, there were at least two

other major reform efforts occurring in these

communities

at the

same time—the Alaska Rural Systemic

Initiative, which attempted to integrate

Indigenous knowledge and curriculum into

the formal

educational system, and the Alaska Quality

Schools Initiative, the state-driven standards

movement that also included a family-community

partnership component.

The case studies attempted to document these

reforms over a two-year period (1996–98),

with a strong focus on AOTE and how it contributed

to a more systemic approach to

educational change.

In trying to understand

community-based systemic reform, our case

studies focused on a key

variable we called

community voice. Community

voice

captures the essence

of what we believe to be the important elements

of a productive educational partnership between

schools

and

communities

in remote Alaska villages.

Our working definition of community voice

included four components:

- shared decision making, or the extent to which community members

(parents, elders, and others) have greater influence and decision-making

power in educational matters

- integration of culture and language, or the extent to which Native

language, culture, ways of knowing, and a community’s

sense of place are woven into daily curriculum

and instruction

- parent/elder involvement in educating children, or the extent to

which parents, elders, and others have a strong presence and visibility in

the school and

participate in their children’s education

at home

- partnership activities, or positive examples of the school and community

working together to share responsibility for student success

Methods:

Participatory Research

Researchers, school personnel, and community members

collaborated on this study, mirroring the

very partnership process we

were trying to

understand.

We used

a participatory action research approach

that treated school practitioners and community members as co-researchers

rather

than just “subjects” of

study (Argyris & Schon, 1991). Too

often, research has been conducted on rather

than with Alaska Native

people, based on external frameworks and

paradigms that do not recognize the issues,

research questions,

and worldviews of those

under study. For each community, a senior

researcher from the Northwest Regional

Educational Laboratory

or University of Alaska Fairbanks led a

small team of

three to five school and community researchers

who helped plan each case study, formulate

guiding questions,

collect data, and interpret results. In

addition to the senior researcher, a typical

team consisted

of a school district practitioner, a village

school practitioner, at least one non-school

community member,

and

in some cases a high-school student. The

teams included both Alaska Natives and

non-Natives who lived in

the communities under study. This team

composition resulted in a greater awareness

of what happens daily

in schools and communities,

access to others who served as key informants,

and a deeper understanding of history,

culture, and relationships

present in each community

The research

teams used traditional case study methods,

including document analysis,

participant

and researcher

observation,

and surveys and interviews.

Concept mapping was also used to more fully

understand the many simultaneous reforms

happening in these

communities. We followed

a pattern of

collecting data via site visits and then

meeting several times a year in a central

Alaska location to share and discuss results.

Each senior researcher spent approximately

10 to 12 days on site during three or four

separate visits across two school years

conducting interviews,

observations,

and collecting

information

on

school practices and student outcomes.

Most of the community teams, with guidance

from their senior researcher, also collected

data on their own in the form of participant

observation,

formal

surveys,

and formal

and

informal

interviews.

We met in Anchorage six times (12 days)

throughout

the study

to work in small village teams and as a

whole group to design data

collection

techniques,

discuss and interpret results and plan

the next steps. Senior researchers met

together

an additional four times (8 days) to plan

the

study and outline and write up the cross-case

findings.

In this

way, we refined

our initial

research

questions

and data collection techniques as we engaged

together in constant-comparative analysis.

Results:

Community Engagement and Systemic Reform

Each

community/school case study provided a rich picture of community engagement,

parent involvement,

and systemic

reform.

The cross-case

analysis surfaced

some broader reform themes that are the

focus of discussion here. Four major

themes related to successful community engagement

and parent involvement are presented

below. Excerpts

from selected

case studies

are included as

sidebars and

throughout the body of the paper to bring

the

key results to life.

Sidebar 1

It’s All About Teachers

Tatitlek Study/Sarah Landis When the senior researcher asked the residents

to describe any factors that have contributed to school change

and improvement, most shared their

viewpoints first and foremost on the importance of the [two husband

and wife] teachers. Tatitlek residents’ inclination was not to talk

about programs, but to describe the skills of individual teachers. A

village elder commented on the teacher skills in working with the community: “Those

Moores, they have the Native people figured out. They know how to work

in the village, when to get involved, how to make things happen.”

The

village chief also attributed program improvements to changes in

specific school staff: “Those new teachers worked hard and put

tireless energy into promoting the programs.” In retrospect,

the chief said he wished that he had worked harder for better staff

in the

past.

Another community member expressed the viewpoint that, over

the course of time, “Community interest in and commitment to

schooling fluctuates with the teachers and with the teachers’ attitudes

towards the Natives.” She went on to contrast the current teachers

with their predecessors: “The previous teachers kept to themselves.

They did not allow their own children to play with the other kids

in the village,

and they themselves did not associate socially with the rest of the

community. They called students stupid and hopeless. But the Moores

have changed

all of that. They value the Native lifestyle.” From her perspective,

the current teachers are seen as part of the community because of

their own interest and skills, and because their own children intermingle

easily

with the Native children. |

Sidebar 2

Working From the Inside-Out

Aniak-Kalskag Study/Bruce Miller Alaska Onward to Excellence might be improved if it began with a core

group of motivated individuals from each village that spends time identifying

key community networks and individuals who can positively influence the

community and school. They would engage these individuals in a dialogue

about the school and community in terms of their work. In other words,

learn what they do, discover their interests and desires, and engage

them in their ideas for supporting and helping youth. The focus is aimed

at building relationships and the common ground upon which to make improvement

decisions.

Classroom-level examples of the kinds of communication necessary for

engaging and sustaining such relationships were discovered during interviews

with teachers and parents The common pattern across these examples reflects

teachers going out of their routine roles to interact with parents and

community members in ways that demonstrate genuine caring for students

and an understanding of local context and place. In some cases it was

persistent phone and face-to-face contacts in and out of the school.

In other cases it was using local resources and people to contextualize

learning. Moreover, the examples found in both Aniak and Kalskag of these

types of relationship-building behaviors occurred with young teachers,

senior teachers, new teachers, Native teachers, and non-Native teachers.

These examples have much to teach us about how reform and improvement

can occur in village life. Moreover, such a focus builds on local assets

and resources as opposed to building on problems and needs. |

Building Relationships

and Trust as the Basis for Successful Reform

To varying degrees, the individual

case studies showed how a reform process

like AOTE, which

includes concrete

ways

for the

school

and community

to continuously work together over

the long-term, can be a powerful tool for

change. However,

the larger lesson was that relationships

and trust between school and community

people provided

the

foundation for

successful partnerships.

This was magnified

in the two very smallest communities.

The community of Tatitlek, for

example—located

near Valdez with about 100 residents,

23 students, and a husband and wife

teaching team—demonstrated

how teachers who came from the outside

gained the trust of the community

by

taking the time to understand the

community’s

traditions and heritage and use this

knowledge to create meaningful educational

experiences

for the students (see sidebar, It’s

All About Teachers)

An important lesson

learned in these communities is that too much emphasis can be put on process

and procedure from the outside and not enough on building

relationships and trust from the inside. The Aniak-Kalskag case study

in western Alaska found that to be effective, an external process like AOTE

needs to work

from within the local context and build on the relationships that already

exist (see sidebar, Working From the Inside-Out). This inside-out approach

can lead

to sustained community engagement and ownership for the reform work.

In

contrast, when personal relationships with key village leaders and

residents were not

nurtured as part of the reform process, a familiar pattern emerged throughout

the case studies—fewer and fewer community people participated in

AOTE-sponsored reform activities as time went on. It makes a big difference

whether people perceive that they are being called upon to carry out someone

else’s reform agenda, or if they come to interpret the message as, “let’s

work together to raise healthy children for our community.”

Finally, two-way communication, particularly

between Alaska Natives and non-Native

educators, is an

important factor

in building

the strong relationships

and

trust that can sustain reform in

rural Alaska communities. Vignettes

in some

of the case

studies illustrate

the extent to which Alaska

Natives continue

to feel alienated from the school

system (see sidebar, When Two-Way

Communication

Breaks

Down). Many Native

adults had

negative school

experiences in boarding

schools, where they came to feel

that their knowledge and worldview

had no

place in

the formal education

system. This is certainly

changing in

rural

Alaska, yet the hurt of past experience

lingers. There is still a healing

process going

on, and a process like AOTE—if

implemented with a clear sense

of creating genuine community voice—can

accelerate that healing.

Parents

and Teachers Must Learn

New Roles

The case studies illustrated

how educational partnerships require

new behaviors,

roles, and ways of thinking

on the part of both

school personnel

and community

members. Many educators and parents,

however, are stuck in traditional

roles and are

not sure how

to change

even if

they want to. When

asked about how

much voice she had in the school,

one parent replied, “I

don’t

know how I am supposed to have

a voice.” Those words represent

a larger finding of the case

studies: while it is easy to

talk about

creating partnerships between

school and community, changing

the traditional roles, behaviors,

and attitudes is a difficult

process for both school personnel

and parents.

Some of the communities

were stuck in what Joyce Epstein

(1995) calls the “rhetoric

rut” in

which both school personnel and

parents talk about and support

the idea of parent/community

involvement but do not know how

to get there.

A parent survey

conducted by the case study team

from Klawock in southeastern

Alaska (an island town with about

750

residents and 200 K–12

students) illustrates how both

parents and teachers see limited

roles for parent involvement.

The Klawock case study team designed

and conducted a survey of the

community and

teachers to dig

deeper into

the issue

of how

parents

and teachers

view the parent role in education.

A random sample of 40 parents

from the

Klawock

City Schools (representing about

one-third of all parents) either

completed a

mail survey or

were

interviewed if the survey was

not returned. A

parallel teacher survey was also

completed by 13 teachers

(nearly all the teaching

staff). Survey items used Epstein’s

(1995) parent involvement framework

and asked parents and

teachers to rate the importance

of twelve specific parent involvement

activities in five categories:

parenting (help families

establish home environments that

support learning), communicating

(effective school-to-home and

home-to-school information sharing),

volunteering

(parents helping

in classrooms and the school),

learning at home (helping parents

guide children through homework

and projects), and decision making

(including parents in school

decisions and school

improvement

efforts like AOTE).

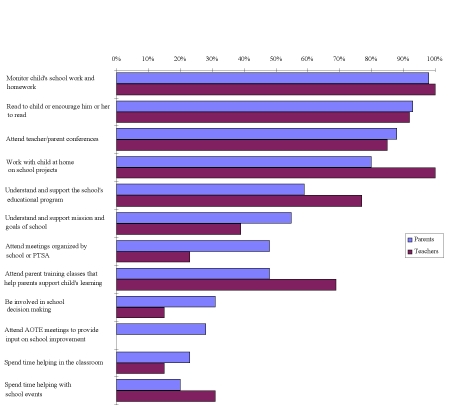

Figure 1

presents the parent and teacher

ratings of “very important” activities—that

is, activities busy parents would

likely make time for and that

teachers would encourage parents

to pursue. The results indicated

that nearly all parents

saw their major role as supporting

their children’s education

at home by monitoring school

work and homework, reading to

their children or encouraging

them to read, and working at

home on school projects. Parents

also felt that

parent/teacher conferences are

an important communication activity.

Teachers tended to agree here

with parents. Next were activities

where parents and teachers

ascribed less importance to the

parent role: understanding and

supporting the school’s

educational program and mission/goals

and attending

parent-teacher-school association

meetings

or parenting classes. Finally,

and most important for

a process like AOTE that encourages

full community engagement, both

parties indicated that some activities

were far less important: parent

involvement

in school planning and decision

making (including AOTE meetings)

and volunteering in the classroom

or school.

Figure 1.

Percent of Parents and Teachers Who Rate

Various Parent Involvement Activities as “Very Important” (Klawock

Survey).

Sidebar 3

When Two-Way Communication Breaks Down

Klawock Study/Jim Kushman

Parents in Alaska Native communities can feel

marginalized because of poverty, a sense of cultural isolation, or

their own negative experiences with schools, both past and present.

The story of Bill (not his real name), an Alaska Native single father

with two school-age children, illustrates how deep the barriers to

trust can become when parents and schools fail to understand each

other and actively communicate. Bill characterized his own education

in a boarding school as “a place where 90% of the teachers

didn’t care if students passed or not,” but was generally

positive about the present-day teachers in this community’s

school and their caring for students. Difficulties do persist, however.

Bill pointed out that it is difficult for many

Alaska Native parents to work with the schools because they do not

understand what the teachers are doing. Bill felt that he certainly

could not help his daughter with her middle-school math since he

only had a ninth-grade education himself. He firmly believed that

it is not the parent’s role to teach academic subjects: “I

run my business, I’m not a teacher, I can’t come into

the school and teach math!”

Bill was most concerned about his 11 year-old

son Sam who was in special education. He characterized Sam’s

experience in the regular classroom as the teacher “giving

him five problems to work on while the other kids get 20 problems.” The

other kids excel and Sam falls behind. Bill said he has gone to the

school and talked to many people about Sam’s problems—teacher,

principal, superintendent, and finally the school board—but

to no avail. “I go down there, I tell them what’s on

my mind, I get no response; then I get angry and communication shuts

down.” I asked why he thought it was like this. He answered

that cultural differences are part of it. He felt that non-Native

parents are more “aggressive” than Native parents as

a matter of style, and the school is more likely to listen to the

louder voices. He felt that he shouldn’t have to be “pushy” to

get what his children deserve.

A year later when I interviewed Bill again, he

was feeling even more alienated. After an outside child advocate

intervened, Sam received one-to-one tutoring and was catching up.

But because of changes in special education criteria, Sam stopped

receiving the tutoring and was falling behind again. Bill expressed

his anger and confusion at this sudden shift in policy, with no real

explanation or help coming from the school.

Given his past experiences in school, his low

sense of efficacy as a parent educator, and the insensitivity he

experienced over his son’s problems it is no surprise that

Bill felt deeply alienated. Yet in the abstract, he firmly believed

that schools and parents must work together through community-based

processes like Alaska Onward to Excellence. |

Sidebar 4

There Are Many Ways For Parents to Become Involved

Quinhagak Study/Carol Barnhardt

Many parents in Quinhagak are now directly involved

in their school because they are serving as the school’s teachers,

aides, cooks, custodians—and principal. Several community members

serve their school in other positions. Those on the Advisory School

Board deal with matters ranging from setting the school calendar

to approving changes in the school’s bilingual programs to

assisting in establishing budget priorities to annual approval of

the school’s principal. The AOTE process also provides opportunities

for community members to serve on leadership teams and broader participation

through its community-wide meetings and potlucks. Other venues for

direct participation include the Village Wellness Committee Team

and the school Discipline Committee.

Some family members participate in less formal

ways through volunteer work in their children’s classroom or

as chaperones on trips. Others contribute through efforts in their

own homes (e.g., providing a quiet place for children to study, reading

with and to children, reviewing homework assignments with them).

A description of 15 initiatives that were designed to promote increased

parent, family, and community involvement and participation in the

school were identified by the school in 1997. There were 119 volunteers

and 1,500 hours of volunteer services in 1997–98. The 15 initiatives

included:

- Let’s Learn Together: Program that rewards parents, siblings,

or community members who volunteer at least 10 hours in the school

during the academic year with a T-shirt with the words “Let’s

Learn Together—Quinhagak, Alaska” in both Yup’ik

and English. These shirts are available only from the

school and are worn with pride.

- Home-school journals: Students write weekly letters or notes

to parents or other older family member and receive a written reply.

Journals are also used for parent and teacher written correspondence.

Students know that their teacher(s) will be in contact with their

parents on a weekly basis.

- Migrant education program: Federal money is used to hire community

workers who visit students and their parents in their homes during

non-school hours to provide assistance with reading for both students

and their parents.

- Adult Yup’ik language program: School sponsors an adult

Yup’ik language program that provides opportunity for parents

and other interested community members to learn to read and write

in the Yup’ik orthography that is used in the school. (Many

of the elders learned to use an older system developed by the Moravian

Church.). When the class is offered on the same nights as the Computer

Night, attendance is better because family members can come to

the school together.

- Computer nights: The school is open two or three nights a week

for parents to learn to use computers. Parents can bring their

children to help them.

|

Sidebar 5

Reform as A Means to Bridge Two Worlds

Yupiit-Tuluksak Study/Ray Barnhardt & Oscar Kawagley

While there continues to be some significant differences

of opinion regarding how to proceed in integrating the Yup’ik

culture with the standard academic curriculum, the comment of one

of the teachers that their task is to help students “walk in

two worlds with one spirit” best signifies the direction that

has begun to emerge. For the majority of the teachers who originate

from outside the communities and culture in which they are working,

such a task poses a major challenge, but as a result of the AOTE

dialogue they saw the need and were willing to make the effort. Instead

of the community having to make all the accommodation to meet the

imported expectations of the school, at least one teacher was encouraged

that “the school is finding its way to the community.” The

Yupiit School District (YSD) experience indicates that it is possible

to approach the infusion of culturally appropriate content and practices

into the curriculum through an integrative rather than an additive

or supplementary approach. By carefully delineating the knowledge,

skills and values students are to learn in culturally appropriate

terms, and employing a variety of “teachers” who possess

the necessary local and global cultural knowledge and perspectives,

it is possible for a school district to provide an integrated educational

program that builds on the local cultural environment and Indigenous

knowledge base as a foundation for learning about the larger world

beyond. Learning about ones own cultural heritage and community should

not be viewed as supplanting opportunities to learn about others,

but rather as providing an essential infrastructure through which

all other learning is constructed. Clearly, this would not have happened

without the kind of extensive school-community interaction that AOTE

fostered.

These and many other lessons can be gleaned from

the experiences of the communities that make up the Yupiit School

District in their efforts to accommodate two cultures in the schools.

But most of those lessons are of little use to others unless they

also possess the sense of cultural pride, dignity and determination

that is reflected in the people of Akiachak, Akiak and Tuluksak.

The impact of the AOTE project on schooling in YSD is best captured

by the statement of a parent in summarizing the significance of the

mission statement that had been adopted by the YSD board with a paraphrase

of an old African adage: “It takes the whole village to educate

a child.” The villages of the Yupiit School District are making

that adage a reality. |

Sidebar 6

Helping Rural Students Make the Transition

Tatitlek Study/Sarah Landis

Anchorage House was designed by the Chugach School

District to provide village students with opportunities to receive

skills training, explore after-graduation options, and apply their

learning in real-life situations. To accomplish this purpose, the

district has purchased two houses in Anchorage at which village students

stay while engaged in learning activities in the following areas:

life skills, personal development, social development, service learning,

urban familiarization, and career development. Activities are organized

around exploration in five outcome areas: entrepreneurial, business,

postsecondary education, service learning, and skilled trades. Students

attend Anchorage House in phases:

Phase 0: Introduction to Anchorage House is

intended for younger kids (middle school) to introduce them to Anchorage

House and get them started in the program. This phase lasts only

a few days.

Phase 1: Search Week lasts for

approximately one week. Students and staff live, eat, work and, learn

together during this intensive week. During this time, many of the

activities focus on self-awareness, problem solving, trust, conflict

resolution, resiliency, team building, urban understanding, and exposure

to a variety of career and postsecondary choices.

Phase 2: Earn to Return is about

one month in duration (broken up into two visits) and offers opportunities

for successful, dedicated graduates of phase 1 to act as facilitators

with other students. Phase 2 is focused on engaging students in job

shadowing. At the end of the phase, students are able to look for

and secure a job, use resources for counseling and personal finance,

live independently, eat, clean, and travel on their own, and have

a good understanding of areas they wish to pursue.

Phase 3: Pathways provides an

opportunity for “independent” living and emphasis on

life after high school by engaging students in various career exploration

and internship programs. For approximately one month, students are

supported to enable them to move toward independent learning while

they are also given a more in-depth exposure to what career settings

require and employers expect. By the end of phase 3, students are

responsible, self directed, and have a good understanding of where

they wish to spend their time for phase 4.

Phase 4: Create Your Future is

a 6-to-12 month supervised, self-directed, independent living and

learning experience. The students who have completed the prior phases

and have been successfully matched with an employer, institute or

small business start up will gain specific technical skills, and/or

college credit, through hands-on learning, closely integrated with

school-based activities. |

The survey asked parents

if they were involved as much as they

would like

to be and 70%

answered “yes.” Respondents

were also asked to consider

a number of factors that might

hinder parent involvement.

Not

surprisingly,

the most inhibiting factor

for parents was time and scheduling—this

item was checked by nearly

two-thirds of the parents,

the majority

of whom were “working” rather

than “at-home” parents.

Beyond the time issue, an important

inhibiting factor for many

parents was that they didn’t

know what their options were

to become

more involved in the school.

This mirrors the earlier parent

concern, “I don’t

know how I am supposed to have

a voice.” Interestingly,

teachers cited the most inhibiting

factor as parents not feeling

comfortable coming to the school.

What teachers saw as “discomfort” may

have been a reflection of parents

not knowing what their options

were.

The parent survey results

were analyzed by race to see

if

there were differences

between

non-Native

and Native

parents.

All

of the analyses

revealed similar

views and opinions across racial

groups. Native parents

felt just as comfortable coming

to the school as non-Native

parents, and

if anything

were less likely

to endorse the statement, “I

don’t think the school

is interested in my involvement.” Native

and non-Native parents also

had similar patterns in their

role conceptions—they

saw themselves more as good

parents supporting education

in the

home than as classroom volunteers

or school decision makers.

These results reveal challenges

many small rural communities

may face

when trying

to bring school

and community

together. Beneath

the rhetoric

of

greater parent involvement

are beliefs about when and

how parents

should

be involved. In this one small

community, parents and

teachers saw the parent role

as being good parents and

promoting learning at home,

which are very

important

factors

for student success. But absent

were conceptions of

more expanded parent roles

that characterize partnerships—parents

as school volunteers, decision

makers, and active participants

in improvement work. Without

a compelling

goal

deeply rooted in community

values, such as preserving

language and

cultural knowledge in Alaska

Native communities, many parents

and community

members

may be content to leave education

to the educators.

In contrast

to Klawock, the western Alaska

community of

Quinhagak

(consisting of

about 550 residents,

many of whom

are fluent

Yup’ik speakers, and

125 K–12 students) exhibited

a strong sense that the school

belongs to the community—as

evidenced by the school’s

name, Kuinerrarmiut Elitnaurviat,

which few non-Yup’ik

speaking people are able to

pronounce. Quinhagak illustrated

how parents, elders, and other

community members could

work in the school as paid

workers, as unpaid volunteers,

and as educators in the home.

Given a strong commitment by

everyone to the goal that students

will be educated to speak both

Yup’ik

and English, community members

were certainly made to feel

they had important knowledge

to offer

the formal

education system. The Quinhagak

case study exemplified that

with energy and creativity,

many new

roles can

be constructed for parents

and community members to become

involved

in the school when there is

a shared goal that reflects

success

in both the school and community

(see sidebar, There Are

Many Ways for Parents to Become

Involved).

Through this strong

parent-school partnership,

Quinhagak and the Lower Kuskokwim

School

District have built an exemplary

bilingual

program for Alaska Native students.

Schools

Must Understand and Practice

Shared Leadership

The

case studies provided multiple examples of reform

led by strong

superintendents and principals

who provided

the

leadership

necessary

to keep the improvement

process moving forward. However,

strong leadership from the

top is not enough,

and in fact can

sometimes hinder

rather

than help

a community-guided

reform

process. The important distinction

here

is between leadership as

a shared decision-making

process

and top

down leadership that invites

community input rather than

full community engagement.

Districts and villages

with a tradition of top down

management had difficulty

making a transition

to shared

decision making.

District

and school leaders need to

clearly understand

that with

a community-driven

reform process,

they are buying into

a different

way

of making educational

decisions. Furthermore, when

a district buys into shared

decision making,

it must follow

through on its commitment

and not choose

to exercise

veto power

just because a decision didn’t

adhere to the administrative

position. A community will

quickly sense when district

leaders are not “walking

the talk,” and this

will seriously erode trust.

Strong

superintendent and principal

leadership helps

drive reforms.

Yet the case studies

also attest to

the limitations

of top down

leadership and illustrate

how shared leadership helps

districts and communities

sustain reforms.

Shared leadership

creates

the high degree of community

involvement

and

ownership

that can sustain educational

reform despite the frequent

superintendent and principal

turnover that occurs in rural

Alaska

schools.

In the community

of Tatitlek, where most of the leadership

at the time

came from

the superintendent,

there was

little evidence

of

shared responsibility

for student success. Once

the community provided

input to

the mission and

goals, there was

little further

interest in being

involved

because changing

educational

practice was viewed as

school work led by a strong

superintendent rather than

school-community work.

Many innovative changes

in curriculum, instruction,

and assessment were in

fact implemented

by the superintendent,

but with

little

further involvement by

the village council and community

members—even

for things like cultural

fairs, which require a

high degree of

school-community collaboration.

A point of contrast to

the superintendent-oriented

leadership

apparent in Tatitlek

and the Chugach School

District was Quinhagak

and the

Lower Kuskokwim

School

District (LKSD), where

shared leadership coupled

with shared

responsibility

has been consciously

practiced for many

years. Shared decision

making is part of the organizational

culture at the district

office and

throughout many village

schools in LKSD. In the

case study site of Quinhagak,

the real reform

was

exercising local control

of education. The external

reform

model—in this case

AOTE—was

merely a means to this

end. In 1995, LKSD embraced

AOTE

as a way

to move from traditional

district strategic

planning to the district

working with schools and

local communities

to share decision making

and responsibility for

student success.

This fit nicely with an

established district practice

of using

the local school advisory

committees

for more than just giving

advice. Advisory

committees are involved

in core decisions, such

as how

the school

budget would be spent,

the kind of

educational programs that

would be put in place,

and selection and retention

of

the

school principal. The district

invested in training local

advisory board members

in areas like the

school budget so

that they would

have the capacity to make

sound decisions. This is

true shared decision making

rather than the

rhetoric

of shared decision making.

Coupled with the strong

district support

for the Quinhagak bilingual

program, which the community

truly

embraced, a long-term partnership

has emerged involving

district leaders, school

leaders, and community

leaders who work

together and share responsibility.

The Goal of Educational

Partnerships is Healthy

Communities

The Alaska

case studies focused on understanding

how rural

districts, schools, and

communities can work

together to

achieve greater

educational attainment

for this generation and

future generations

of students who must “walk

in two worlds with one

spirit.” Another

important theme generated

from the case studies

is that education

in rural Alaska has a

larger purpose than

teaching academic skills

and knowledge. The AOTE

community-based process

brought out the deeper

hopes,

dreams, and fears of

communities that are

trying to preserve

their unique identity

and ways of life while

still

preparing their

children to live in a

global and technological

world.

The AOTE vision-setting

process

resulted in as many community

wellness and character

education goals as

academic

goals. People expect

the education system

to help

young people respect

their elders, respect

themselves, stay sober

and drug free,

learn self-discipline,

and contribute to the

well-being of their community.

Some

schools and communities

tried to achieve a broader

definition of “educational

reform” than narrow

academic goals, and some

saw academic goals

as a means to community

wellness rather than

an end in itself.

There was a clear

sense that education

and community health

are inextricably

linked.

Schools and communities

in rural Alaska are

challenging themselves

to simultaneously achieve

high

cultural standards

and high academic standards

as a means to improved

community health

(see sidebar, Reform

as a Means to Bridge

Two Worlds).

Finally, education is

ultimately a means to

prepare students

for making a life

and a living

both

inside and outside

of the village.

The communities

we studied

were working hard to

simultaneously preserve

their culture,

language, and

subsistence

ways, while

at the same time

pursuing student

goals such as

post-secondary

education and successful

transition to careers

outside of the village

(see sidebar,

Helping

Rural Students

Make the

Transition).

These

communities realized

that

there are many pathways

to success

and that

schools must prepare,

encourage and support

students in

whatever path

they choose.

Conclusions and Discussion

The Alaska case studies

of educational reform

point to many hopeful

signs that rural schools

and small

communities

can

work together

for the benefit

of all

young people. When parents,

elders, community members,

and school

personnel begin to

see that they share

something in

common, they

do come together.

In the communities studied

a shared vision for student

success

with

explicit learning

goals was created through

the Alaska Onward to

Excellence

process, which

included a

series of

scripted community

meetings that

brought community

members into

the conversation. In

rural Alaska, this vision

was

typically to

develop young

people who “can

walk in two worlds with

one spirit,” to

quote a teacher from

one of these communities.

The

goal was to educate

students who

are literate in their

own Native language and

subsistence

culture,

and likewise are prepared

to read, write,

compute, think, and live

successfully in the world

outside of rural Alaska.

This continues to be

a challenging goal in

these communities,

but one which people

adhere to through the

many setbacks

and personnel changes

of multi-year

reform efforts. Establishing

a vision that the school

and community

share is a good start,

but it is not enough.

The

cross-case analysis points

to at least four essential

characteristics of successful,

sustainable partnerships.

First,

small rural communities

are built on interpersonal

relationships more than

on formal

processes.

Reform efforts will be

more successful if they

take an inside-out approach

and build

on these relationships.

This

means seeking out the

strengths, assets,

and local

sense

of place and culture

that make a small community

unique, and then

designing a

reform effort

that fits

this context.

This is a different style

than

working strictly from

an

external reform

model that includes

many

prescribed

steps

and often

starts from a framework

of

untested assumptions

or perceived community

deficits. An important

step in this

approach is consciously

building

good relationships

among

school personnel, parents,

elders, and non-parent

community

members – groups

who often start out with

a degree

of mistrust,

ill-feelings, and misconceptions.

Relationship-building

requires constant two-way

communication

between the school and

community, including

communication through

the informal people networks

in small villages and

towns.

Second, parents

and school personnel

are often locked

into a view

that the home

and school

are separate

spheres of

influence, to

use Joyce

Epstein’s

(1995) terminology. It

takes more than just

talking about

the need

and importance of parent

involvement to unfreeze

this mindset. Parents

must learn new

roles

and teachers need to

change

their views about how

parents should

be involved. It is easy

for teachers and parents

to become

locked into

blaming each other

for low parent involvement.

This blaming is due in

part to the frustration

that naturally occurs

when

people are asked to change

old attitudes and behaviors.

In

Alaska Native communities,

the last generation of

adults was given

the clear

message that their knowledge,

culture, and language

had no place in the

school.

The message has changed

but it will take time

and effort

for people

to become comfortable

and skillful in exercising

new

parent roles in which

they share decision making

responsibility.

Schools

also need to move beyond

a few narrow

parent

involvement

options and

make accommodations

for

parents with busy schedules,

different

backgrounds, and different

comfort levels. Too often,

parent involvement

is viewed

as a

one-way street whereby

parents are expected

to be the passive

supporters

of the school’s

agenda. The lesson from

these case

studies is that parent

involvement must

be seen as a two-way

partnership in which

parents and teachers

work hand in hand to

make what students experience

in school and the life

they lead outside of

school complementary.

This is especially crucial

in Alaska

Native communities where

the language and culture

of the community need

to

provide the foundation

for

the school curriculum

and teaching

practices.

A third essential

ingredient for successful

partnerships

is moving

from top-down

leadership to shared

leadership. Superintendents

and principals

with strong

leadership skills are

certainly important in

rural Alaska,

where sparse conditions

and geographic

isolation place unusual

demands on

managing

a school. However,

the more that leadership

is shared with the community

and

teachers,

the more

a reform

effort will likely

become part

of the community

fabric instead of

the latest fad of the

current administration.

People

in rural Alaska have

seen numerous school

reform

initiatives

come and

go over the years,

only to be

replaced by a recycled

initiative under

a new

name with each new principal

or superintendent (or

legislature) seeking

to make

his or her mark on the

educational landscape.

If school reform

is to

become sustainable over

time, it

is going to have to shift

from a top-down

to a

bottom-up approach so

that the ownership and

commitment

that is needed is embedded

in

the community. Reform

must become

something

that community

members

embrace and contribute

to, rather than something

that

someone else does

to them. The

purpose of the reforms

must be clear and widely

supported if they are

to last

beyond the tenure of

the current proponents.

Reform

for reform’s sake

has no durability and

is likely to become an

obstacle

to meaningful

long-term change.

Finally,

educational reformers

need to realize

that in

places like rural

Alaska,

there is

a strong link

between

educational

improvement

and community

health.

These are overlapping

goals for small rural

communities.

Schools

have an

important role in community

development and educators

should work

to develop

educational

programs that not only

address high academic

standards, but that promote

high cultural standards

for Native

groups and

help students

develop

the respect, self-esteem,

and other character goals

that

contribute to academic

success.

Students in rural Alaska

are often

caught in a tug of war

between their identity

as members

of

the Indigenous

culture

and the

pervasive influences

of the

outside

world, particularly as

manifested

in the

school and on

television. In the current

frenzy over high academic

standards,

the focus

of schools becomes

limited to

academic development

alone and as a result,

risks contributing

to disaffection,

aimlessness,

and

alienation among

students in rural

Alaska. Guidelines

for overcoming this limitation

of schooling

have been spelled out

by Native

educators in the Alaska

Standards for

Culturally Responsive

Schools. Following

are the main points put

forward by the Alaska

Cultural Standards

to address

this issue.

- Culturally knowledgeable students are well grounded in the cultural

heritage and traditions of their community.

- Culturally knowledgeable students are able to build on the knowledge

and skills of the local cultural community as

a foundation from which to achieve personal

and academic success

throughout life.

- Culturally knowledgeable students are able to actively participate

in various cultural environments.

- Culturally knowledgeable students are able to engage effectively

in learning activities that are

based on traditional ways of knowing and learning.

- Culturally knowledgeable students demonstrate an awareness and appreciation

of the relationships

and processes of interaction of all elements in the world around them.

These are

the major lessons that have been gleaned

from the case studies

of communities involved in Alaska Onward

to

Excellence and other

systemic school

reform initiatives

in rural Alaska. While the findings are framed

by the Alaska landscape,

they are readily generalizable to rural schools

and communities

anywhere. Inherent

in the case study findings is the notion that education is first and

foremost a

local endeavor. By understanding how such

an endeavor is played out in the local contexts

of rural Alaska,

we can also understand

better how it might

be played out in any

other local context.

References

Annenberg Institute for School Reform

(1988). Reasons for hope, voices

for change: A report of the Annenberg Institute

on public

engagement

for public

education. Providence,

RI: Author.

Argyris, C. & Schon, D. A.

(1991). Participatory

action research and action science compared:

A

commentary.

In W. F. Whyte

(Ed.), Participatory Action Research, 85-96.

Newbury

Park, CA: Sage

Publications.

Barnhardt, C. (1994).

Life on the

other side: Alaska

Native teacher

education

students and the

University of Alaska

Fairbanks. Ph.D.

dissertation, University

of British

Columbia.

Barnhardt,

R. & Kawagley,

A. O. (1998).

Culture, chaos and complexity:

Catalysts for

change in Indigenous education. Fairbanks: Center

for Cross-Cultural

Studies, University

of Alaska Fairbanks.

Epstein, J. L.

(1991). Paths

to partnership:

What we can

learn from federal,

state, district,

and school

initiatives.

Phi Delta Kappan,

72(5), 345-349.

Epstein,

J. L. (1995). School/family/community

partnerships:

Caring for

children we

share.

Phi

Delta Kappan,

(May issue),

701-712.

Epstein,

J. L. & Hollifield,

J. H. (1996).

Title I and school-family-community partnerships:

Using

research

to realize the potential. Journal of Education for

Students

Placed At Risk, 1(3), 263-278.

Griffith, J.

(1996). Relation

of parent

involvement,

empowerment,

and school

traits to

student academic performance.

Journal

of Educational

Research,

90(1), 33-41.

Henderson

A. & Berla,

N. (1994).

A new

generation

of evidence:

The family

is critical

to student

achievement.

Washington,

DC: National

Committee

for

Citizens

in Education.

Hoover-Dempsey,

K. V. & Sandler,

H. M. (1997).

Why do parents

become involved

in their

children’s

education?

Review

of Educational

Research,

67(1), 3-42.

Kawagley,

A. O. (1995).

A

Yupiaq world

view: A pathway

to ecology

and spirit.

Prospect

Heights,

IL: Waveland

Press.

Thorkildsen,

R., Thorkildsen,

M.

R. & Stein,

S. (1998).

Is parent

involvement

related to

student achievement?

Exploring

the evidence.

Research

Bulletin

Phi

Delta Kappa

Center for

Evaluation,

December

(no. 22).

Waldrop,

M. M. (1994).

Complexity:

The emerging

science at

of

the edge

chaos.

New York:

Doubleday.

Author Note

The authors

wish to thank

the

members of

the research

teams

for their

dedication

and hard

work in

addressing

some of

the most

intractable

problems

in rural

education.

Without their

contributions

and insights,

this

study

would

not have

been

possible.

Senior researchers

from the

Northwest

Regional

Educational

Laboratory

and University

of Alaska

Fairbanks

contributed

to

this manuscript,

as acknowledged

in

the case

study

excerpts

throughout

the

paper.

This

research

was supported

by funds

from the

National

Institute

on Education

of

At-Risk Students,

Office

of Educational

Research & Improvement,

U.S. Department

of Education.

The opinions

and points

of view expressed

in this report

do not necessarily

reflect the

position

of the funding

agency

and no

official

endorsement

should be

inferred.

Copies of

the full

case studies

and

final report

are available

from the

Northwest

Regional

Educational

Laboratory,

and

an Executive

Summary is

posted on

the

Alaska Native

Knowledge

Network web

site

at www.ankn.uaf.edu.

|