|

Alaskan Eskimo Education:

A Film Analysis of Cultural

Confrontation in the Schools

6/Evaluations

WHAT WE HAVE SEEN

Geographically we started by looking at the Eskimo

child in his remote village on the tundra where his surroundings

and all his associations,

apart from school, are Eskimo, and where the ecology and the

traditional home and community exert the maximum influence over the

emotional

and intellectual development of the child. Next, we moved down

the Kuskokwim River to the mercantile and administrative center

of Bethel where. White-dominated economy meets the ecology

of Alaska on its own ground, and White and Eskimo lifeways coexist

in their prescribed areas. Finally, we moved 400 air-miles east

to the modern American city of Anchorage where modern economy

and technology serve to insulate the inhabitants from the full

brunt of the Arctic, though the economy is still dependent upon

the exploitation of this ecology.

Ethnically, the movement is

parallel. In the tundra villages the Eskimo child goes to school

in the most saturated Native

circumstance,

where only the school, traditionally an outpost of the BIA, provides

a model of the White world. In the town of Bethel Eskimos go

to an integrated Native-and-White consolidated state school in a

traditionally

White school culture. The child grows up seeing both ways and

their relation to each other, but in any case, 85 percent of the

student

body is Eskimo. In Anchorage, Eskimo, Aleut, and Indian children

attend a traditional municipal public school system, where these

Natives combined make up only 7 percent of the student body.

Regardless of the Native population of 5,000, Eskimos here are a

tiny minority,

living remote from Native culture and ecology, nearly as engulfed

in the White life style as they would be in Seattle or Oakland,

where school and community are similarly dominated by White

values.

In terms of age cycle, we observed Eskimo children coping

with White education from Head Start, kindergarten, and prefirst

through

to tenth grade, with a focus that documents the changing emotional

adjustment to challenges of White acculturation that dominate

education. We have particularly looked at the changing projection

of stress,

under different circumstances, of the Bethel school and the

Anchorage schools in an effort to determine what is the most fulfilling

learning circumstance that can deal with the psychological

problems of adolescence

in the acculturation and socialization of the Native child.

My

evaluation

will be to examine these three curves of Eskimo development

tracked through the twenty hours of film.

The Geographic and

Environmental Curve

Children in the elementary school in Kwethluk

were more motivated than were the children in Tuluksak, which was

relatively a

more economically depressed community. But the children of

Kwethluk

were also

more motivated and educationally eager than the school children

in the tundra mercantile center of Bethel. In turn the Bethel

children were more motivated than the Native children in

the elementary

school in Anchorage.

Because Bethel is an Eskimo trading center

and the center of salmon fishing, Eskimo culture ebbs and flows

in from

the villages

up

and down the Kuskokwim and nearby areas of the Yukon that

offer Eskimo

children a cultural environmental base of operation. It

is true that the school largely ignored this potential, but

it must have

accounted

for the high level of vitality in both elementary school

and high school in Bethel. The environmental setting seemed

to

influence the high school particularly. The older boys

raced sled dogs

and

competed

in summer boat racing. Many worked full time, fishing through

the summers. Education could well capitalize on these resources

that

are already quietly adding to the well-being of the Bethel

school.

We can conclude that small regional schools can

offer a more fulfilling program for Eskimo students than large

centers

that separate students

from renewing a culture that is locked in ecology. St.

Mary’s

Catholic High School may owe much of its durability to

its regional setting.

The Ethnic Component

Educators have long been aware that there may

be a tipping point in the balance of biracial student bodies, where

behavior can

change rapidly. Our analysis demonstrated this thesis.

In Bethel, where

85 percent of the students were Eskimos, the low

stress was directly related to the relaxed pace set by the

dominant Eskimo group

culture. The high percentage of Eskimos carried the

White 15 percent of the student body along with this pace.

Even the

teacher’s

behavior may have been meaningfully affected by the

Eskimo character of the school culture. This saturation

of Eskimo style certainly

made education pleasanter and more palatable to the

Eskimos and sharply reduced the stress reasonably

expected in acculturation, especially

in adolescent years.

Anchorage exhibited a painful

environment where White pace and values weighed down

the Native students

and made life

intolerable for some

in the schools. Eskimos, Indians, and Aleuts are

a minority in

Alaska and are officially referred to as “the

Native problem,” a

public role that is not one of success. Education

has much to gain by working with the Natives’ ethnic

well-being. There is no evidence that this would

slow the educational process. Quite

the contrary, a relaxed fulfilled student internalizes

and communicates better than the rigid, aching student

who has lost his sense of well-being.

The Age-Cycle

Curve

Consistently in many minority groups in the “Lower

Forty-Eight” (for

example, Blacks, Mexican-Americans, Indians), students

reach a crisis point in adolescence and high school.

This is where the heaviest

dropout rare takes place. And here many minority

students are facing their first bitter inequality

with the dominant society. But in other

cultures adolescence is not necessarily a period

of inevitable stress.

In Bethel High School; adolescence

appeared not to be such an important factor. High

school students

continued to

be relaxed and socially

fulfilled in both community and school. There was

no dramatic dropout rate as adolescence proceeded.

In

Anchorage, as we have stated, this curve was reversed, and Native

students conformed to the conventional

model. Stress

grew higher

with each school year. Reasonably, Native adolescents

were facing the hard realities of being a minority

in a White

man’s world.

Many were faced with severe economic insecurities

that in Bethel would be borne partly by the extended

family culture. Thus, school

became a greater challenge, and education, for

some, became a humiliation instead of a stimulating

fulfillment.

Obviously, as

we have observed on film, White adolescents were

also suffering. But they were White and had the

security of White success to

pull them through. In terms of age cycles in education,

the Native student appears to have a better chance

of fulfillment within his

own supporting environment and cultural group.

These

observations are written about the present acculturation

process in this phase of American

history-now! We are

speaking of circumstances

best adapted to becoming modern Eskimos. First

we must educate for secure, fulfilled, and resourceful

Eskimos.

When we accomplish

this,

the right door to the future will open itself.

No

Basic Differences between School Systems

Our key-sort cards gave

us a rough statistical comparison of the differences and similarities

of Alaskan schools.

These indicated that there is basically no

difference in the education

presented

to Eskimo students by the schools, regardless

of whether the

schools

are run by the BIA, by missionaries, by the

State of Alaska, or by the Anchorage municipal school

system. In working

over the film

to

find areas of similarity and differences, we

found consistently that in all areas related to the educational

approach

and administration-in curriculum, classroom

appearance, educational

materials and

their use, teaching methods, general teacher

behavior,

and teacher

relationship to students-there were no significant

differences between systems.

Indeed it would be difficult to look at any

class in

the sample on

film and be able to identify it as being BIA,

stare, or public school. For this reason the research

team often exhibited

a certain amount of confusion as to which classes

wert in which

system-until

they memorized the code numbers on the film

boxes. To be

sure, within

each school system there were different sorts

of teachers who approached their students in often

widely different

ways, but

each seemed

to exhibit the same range of approaches, with

no major difference between

systems-only between teachers.

All schools teach

the same “White Studies” program.

If there are basic faults in Eskimo education,

these failures are shared

by all of the schools. It is essential to be

absolutely clear on this, for many people with

varying motives feel that emancipating

the Eskimo from the BIA will solve the problem

of Native education. This is fallacious and

hides the true shape of the problem, which

is that White schools in Alaska or elsewhere

in the United States have not met the challenge

of equal education for the ethnically

and culturally different child.

There were fine

and dedicated teachers-and ineffectual teachers-in

all the schools. The

material quality

of the schools in Eskimo

villages is as good as, if not superior to,

that of many rural schools in

the “Lower Forty-Eight.” The schools

on the tundra were, if anything, overequipped.

But any superiority was in terms of the

materials and needs of American culture, and

did not thereby necessarily meet the needs

of Eskimo education.

English, reading, and writing

are all taught intensely in each school. Teaching

skills and

methods were

familiar and

approved;

they were “excellent” for

the most part in terms of standard American

educational practices. If then, the Eskimos

were unable to read and speak clear English,

it means we must question how appropriate these

skills and methods

and equipment were for Eskimos in the Arctic.

We

did not observe any teaching of English as

a second language or any other effort specifically

designed

to bridge the chasm

between the Eskimo and White worlds. There

seems

to be a maddening formula

that the more we “educate” Native

children, the more definite become their problems

of effectiveness and fluency. None

of the school systems in the sample could be

said to balance out this negativity. Possibly

the articulate St. Mary’s seniors

visiting Bethel may have been the result of

an effort to meet this problem in Native education.

The

philosophy of education in all these schools

directs the effort toward assimilating the

Native child. Nationally

schools

follow

the principle laid down by Theodore Roosevelt

that there is no place

in American democracy for two languages, two

cultures, or two different allegiances. Education

for the

minority child

has

always attempted to Americanize him and separate

him from his cultural

distinctions. We saw nowhere in Alaska any

appreciable departure from this philosophy.

The

BIA administration in the Kuskokwim suffers with this challenge

and worries about Eskimo

culture fading.

Indeed

it would sincerely

like to remedy this situation by some variety

of “Ethnic Studies,” but

when faced with action, it has so far backed

down. “Why teach

about Eskimo culture when it is doomed to

be lost?” The Moravian

missionary effort simply rejects the issue

and vehemently opposes Native culture whenever

it competes with White Christian precepts

for the Eskimos’ faith and allegiance.

The state schools supply their libraries

with literature on Eskimo history and culture.

It

is there if the Eskimos wish to read it.

Public schools in Anchorage

also have ethnic studies texts in their libraries.

But these books are looked upon as social

studies; for the most part they are directed

toward White children, explaining the strange

exotic ways of Eskimos-rather than life

studies for Eskimo personality survival. State schools

tend to treat all children “the same,” which

tends to reinforce the unequal opportunities

for Eskimo children.

The BIA schools and teachers

are aware they are teaching Eskimos. Therefore,

they may

be more

responsive to

dynamic change, if

indeed it were ever to be sanctioned. But

we fear this will never happen,

not until all schools together face the issue

of equal personality opportunities for all

children.

Self-Depreciative Effects of White

Education in the Arctic

In filming the Eskimo villages we were impressed

with the block to effective education that

the White educational

compound imposed on

the village’s self image. It is clear

that the schools, educationally, are supposed

to make the villagers look about and attempt

to raise

the standards of village life. This could

be a dynamic influence, but we feel the

negative effect of this demonstration on

Native life

destroys any positive end. Defeat in education

for Native children, and more seriously

later in their mature activities, produces

the

weight of self inferiority that saps confidence

and resiliency.

The educational presence

of White teachers with their White culture-the

affluent White

style

necessary for keeping

teachers in their

jobs in the village schools, whether BIA

or state-creates a serious discrepancy

that in

itself manufactures

deprivation among the

Eskimos. Depreciation of self is a serious

blow to

development; and we

feel that this disposition, created by

the discrepancy that seems inherent in

White

education, is one

of the major causes

of failure

in Eskimo education.

Culturally, it seems

impossible for White teachers in the villages to live in empathy

with the

Eskimos they

are educating.

White

teachers often greatly enjoy and even

admire Eskimos, but the Eskimos’ life

style continues to shock them. Thus,

in the villages a teacher’s

visit with Eskimos is conducted in the

teacher’s home and not

in an Eskimo’s. In Kwethluk, Eskimo

children flooded into the teachers’ compound-and

they were usually welcome-to baby-sit

with the teachers’ children or

just to visit as guests. The wall-to-wall

carpeting

must have fascinated them, along with

the immense size of teachers’ homes,

and the brilliantly illuminated interiors

must have made magazine reading and game

playing a real

pleasure. But how did these children

feel when they walked home over the snow

to

their own small, dark, very crowded cabins?

What

should be the role of the White teacher

in the Eskimo community, a role

that would

motivate students

and at

the same time not

abet their sense of deprivation? We filmed

just one teacher who, we felt, had mysteriously

mastered

this

combination

of teacher

and equal human being. If this role cannot

be mastered,

teachers instruct

over an impossible chasm-a chasm existing

between their world and

the Eskimo’s world. This is a major

cause of the defeat of Native education.

It

is impressive that the Peace Corps rules

out this material discrepancy whenever

it can and

places its

volunteers in

Native villages

at the same level and in the same style

as Native students. The VISTA workers

in

Alaska

are also

required to live

on the Eskimo

level when

working in the villages. In both cases

the goal is to reduce the human differences.

Relevant

Curriculum in Eskimo Schools

The bitterest criticism of the BIA

schools is that they are washing 6ut the Eskimos’ personality.

If critics were fully informed, the charge would be laid against

all schools in the Arctic.

While visiting in Tuluksak, an official

of the VISTA program for the Bethel

region stated, “There is no

relevancy anywhere in the BIA schools.

How do you expect kids to learn with

a curriculum

totally unrelated to their lives?” Later,

with pencil and paper in hand, I

asked him to detail a relevant curriculum

for Eskimo children.

His mouth fell open, and he was unable

to think of one item. A culturally

oriented curriculum that would be

taught by White teachers is indeed

a challenge to construct in the face

of the rapid social change that is

sweeping the Arctic. But at the same

time there is no denying

that the absence of a relevant and

culturally supporting curriculum

is a major fault in Eskimo education.

Our

own records, as we have stared, show

very few and sometimes no items

in Alaska

classrooms

that

would

suggest the schools

were not

in Ohio. The only consistent Eskimo

item we did see was an Alaskan Airlines

poster

that

regularly

presents

Eskimo

portraits.

In

Tuluksak the gamehunter BIA teacher

had a chart of Alaskan furs, and

his wife had two models of Eskimo

camps,

one of which had been made for someone

else. At least 99 percent of all

exhibited materials in schools were

about the “Lower Forty-Eight” states.

The only school that encouraged free-style

art work was the Head Start school;

everywhere else the children colored

Mother Goose dittos. In early

childhood education the only Eskimo-oriented

text was one used in Head Start.

In all other schools, BIA, Mission,

State, and public,

Mother Goose was exclusively the

White goddess of education, and in

the first grade it was Fun with

Dick and Jane. One first-grade

teacher in the state school in Angoon,

which is outside of this report,

used an approved Native Alaska

Reader.

The only class in any school

that studied a standard text oriented to their environment was the BIA

eighth grade in Kwethluk.

We have

just five film examples that record

Eskimo students’ response

to relevant curriculum. The most

outstanding demonstration of relevance

was Head Start in Kwethluk. Not only

were the teachers

young women from the village who

spoke to the children in Eskimo,

but the standard Mother Goose routine

had been sufficiently acculturated

into Eskimo styles of motion and

pantomime, so that the children

responded with delight. The young

teachers did not restrict reading

to Mother Goose, but in addition

used picture books and storybooks

about Eskimo life to stimulate the

children’s interest in reading.

The

second was Eskimo storytelling in

first grade in Tuluksak. The students

did respond

intensely

to this

Native opportunity,

and it

stirs one’s imagination concerning

any contributions that could be introduced

from the villages directly into the

classroom.

Mrs. Pilot also worked with an Eskimo

hunting camp models in an attempt

to stimulate language use. Even when

questioning by the teacher appeared

inappropriate, the model did hold

great interest for the young students.

The

third example on film was made in

the eighth-grade BIA class in

Kwethluk. The

teacher was relating

a standard text

on mental

health to Eskimo life in Kwethluk,

describing

verbally “the cultural

deprivation in the Lower Forty-Eight.” Though

this was essentially a lecture circumstance

with only a minimum of student exchange,

our

film reading describes it as one

of the most responsive classes in

our sample.

The fourth example on

film was the visit of the St. Mary’s

High School seniors to Bethel. First,

as a group they were the most eloquent,

effectual, and assured students observed

in our study.

Second, the Bethel Eskimos responded

with intense listening and expressions

of enjoyment, whereas the White boys

dramatically withdrew in an exhibition

of boredom and rejection.

The fifth

example was in the elementary school

in Anchorage, where an Eskimo

mother gave

a picture talk on life

on St. Lawrence Island.

Though the uniqueness of the circumstance

seemed confusing to the Indian and

White students,

the two

Eskimo boys

did respond openly;

more importantly, the film demonstrated

the competence of an untrained Native

woman to

teach, to present

Native study

material

in a general

classroom.

We conclude that cultural

relevance can appreciably improve reception

and projection

in the Eskimo

student, and that

most texts and

curricula used in all the schools

have difficulty reaching, and often

may

fail to reach, the Eskimo child.

We

feel the issue of relevance in curriculum is an issue related

to

bilingualism.

Both issues are

important,

not

necessarily as means of cultural

retention but more importantly,

as means

of

fluency in

communication that can allow

Native children to conceptualize general

educational content.

Native Teachers

in Eskimo Schools

We filmed only one credentialed

Eskimo teacher in all our sample.

Eskimos

are used as teacher

aides

in the

BIA village

schools

but their teaching opportunities

are limited.

The Charles K.

Ray report on Native Education in Alaska,

released in

1959, made no

recommendations about Native

teachers (pp.

242-243). In the body of

the report mention is made of BIA

teacher

aides, who at that rime were

considered temporary replacements

for qualified

White teachers.

The Ray report

states

that unquestionably,

Native

aides are invaluable for

White teachers,

but the report also expresses

anxiety over their

educational

ability

and stresses

the importance

of weeding out teachers without

training and credentials.

These

expressed attitudes are the heart of the dilemma.

As

expressed

by the

administrator who

asked an advisory

school

board whether

they wanted Eskimo-speaking

teachers, “Of course

there are no qualified Eskimo teachers . . .” In

other words, education

itself blocks the development

of

Eskimo teachers by insisting

that to teach you

must have a credential.

Native

instructors in the Head

Start program demonstrated

the competence

of village

teachers to perform on

a professional level with

minimal

training. OEO gave these

young women a summer workshop

at

the University of Alaska

which was

adequate to make them the

most effectual teachers

of young children filmed

in our Alaska study.

When

we asked a leading Eskimo intellectual in

Kwethluk

what should be added

to the village school,

he answered, “I should

be teaching in that school.” And

what could he teach? “I

would teach our boys

all the things they cannot

learn because they are

going

to school!” He

recognized that the schools

were destroying

Eskimo education essential

for survival in the Arctic.

Yet the Ray report (1959:273)

recommends lengthening

the school year, to include

camping experience.

If

White education had its

way, it would absorb

the

Native child

completely

in

just the same

way the

BIA historically

tried to

absorb the Indian child

in its program of captive

boarding-school

education.

Native teachers

even without college education

and credentials

in the

schools might balance

out this

alarming destruction

of the Native

child’s grasp

on his own life and

ecology,

and offset the hardship

of long hours necessarily

required to complete

school.

We have no illusions

about the simple solution

of

recruiting Native teachers

and organizing

educational experiences

to correct the

racial and cultural

imbalance of White

education. Stepped-up

programs

to

rush teachers through

credential programs

might

not

be a real solution,

because teacher

training itself can

interfere with

the effectualness

of the Native teacher.

We

observed that you can

train and credential

an Eskimo

without

assuring

the result

of a teacher

who can

build the conceptual

bridge between the

White world

and the

Eskimo.

Too often the college-trained

Eskimo comes home a

confused and culturally

schizoid individual.

Training

the Eskimo teacher

to return constructively

to the

village school

will require new

guidelines and a radically

changed philosophical

approach to educating

the culturally different

child.

Unless this

takes place, the value

of the Native

teacher is often

destroyed by the White

backlash of conventional

teacher training.

When

this

happens,

White schools seem

to

educate Natives to

become second-class

Americans.

The Eskimo

teacher

returning to the Natives

can be a harsher critic

of Eskimo ways than

the

White teacher. We have

observed

that Native teachers

who wish

to help

their own people

often impose

the same

harsh routine of education

as they were given

in the White man’s

school, for it is all

they know in terms

of school education.

The

Limitations of White

Teachers and

White Studies

In both

BIA and state schools on the tundra,

we observed

competent, well-trained

teachers

giving

all their

time to educating

Eskimos. Were these professionally

skilled teachers

doing appreciably more for

the Eskimo

children than

incompetent teachers?

The most dedicated

teacher can become

enmeshed in

the web of

White education to

a point where even

his

skilled

efforts turn

off

the Native child.

This was the most

disturbing evidence in our films.

Only one teacher

in the state school

in

Bethel,

Mr. Scout,

seemed to

have freed

himself sufficiently

to teach the

thoroughly White

curriculum, while

at the same time

holding

out an

empathetic hand to

his Eskimo students.

We found

even the

teachers who were

best in terms of

dedication

and training were

unwittingly and with

missionary

zeal

educating the Native

child out of

his basic

foundations of

personality and into an educationally

manufactured personality

that does

not support his needs

in school or later

in

life.

Tragically,

we felt many teachers

sensed

this

but had no resources

to alter

the process. This

haunting suspicion

of failure harassed

teachers in both

BIA

and state schools,

and was

a factor of

the futility

affecting teacher

endurance

in working

with Eskimo

students.

My impression

was that their image

of educational

success

was limited

to Natives’ becoming

modern, civilized

men embracing White

values and ambitions.

Their image of

failure was the

Native student

who goes on being

a bush Eskimo,

as if remaining

Eskimo were a mark of

educational failure.

We talked

to no teachers

who clearly conceived

of their students

becoming modern

Eskimos,

standing firmly

on their

past and perpetuating

their values into

the future. As

Murray Wax observed

about

White teachers

on the Sioux Reservation, “The

Indians’ furniture

was invisible,

and in the teachers’ eyes

they lived in an

empty house” (Wax

and Wax 1964:15-18).

Critics

agree that Eskimos

and Indians

need better education. But

there is considerable

disagreement

as to the goals for Native education

and the kind of

educational program

that

might meet

them.

We agree with many

observers that

schools as institutions

are destroying

Native American

life, simply

because

the content of

schools limits

the scope

of education. Whether

in Alaska or

in the American

Southwest, we find

the same

educational circumstance-that

the schooling of

Native Americans

is

seriously inadequate

not only

for survival in

the American cities

but

for survival

within the Native

environment as

well.

Yet we

also feel

that no schooling

would doom the

Eskimos completely,

so important are

the communication

and technical

skills available

in the White

curriculum,

and so complex

and threatening

has

been the world

surrounding even

the most isolated

Eskimo village.

Eskimo

survival

depends on

new lifemanship

in

the real world

of social

and

technological change.

Our interest together

should

be to envisage

the kind of

education that would

offer Eskimos

and Indians

in

the modern world

the important equality

of participating

as individuals

and

as groups

within the general

society and of

finding fulfillment

within themselves

and

within their own

life styles.

Maybe

we can speak with

more clarity

of the educational

needs of the

Eskimos than

of

Native Americans

at large. For here

we find

hunting and fishing

people within a

relatively unspoiled

ecology

with major

economic opportunities

still

within their

traditional life

style.

We also see a process

taking place that

parallels the

historic

pattern of White

education for

Indians begun a

century

ago.

And we can reasonably

suspect that we

are making, as

White

educators, many

of the same mistakes

that our

predecessors

made

generations ago.

We seem

to learn only slowly,

if at all, about

the dynamics

of

education

for Native

peoples.

The Eskimos

today face a spoils

system

dominated

by

White men

and an invasion

and exploitation

of their

property,

just as

group after group

of Native Americans

did

in the eighteenth

and nineteenth

centuries and as

the Navajos and

Hopis do

now with the

push for

coal-generated

power. With

this history

the

needs for

Eskimo education

now are dramatically

twofold:

- To retain

and enlarge their

environmental

opportunity as

Eskimos.

- To obtain the

special skills

and sophistication

to cope

with the onslaught

of the White

world and cultural

change in general

so that

they can avoid

being

made paupers

on their own lands

or economic

or psychological

failures in

the industrial

cities

to the

south.

Education

toward these ends means

learning

the skills

of their

own culture so

that they can

live providently

within

their

Native environment.

But equally they

must learn skills

and sophistication

in order to

participate in

new technologies.

They

must meet

the White

invasion with

Eskimo solidarity,

economically

and politically,

or they will

effectively be

driven from the

Arctic

completely. Competing

with the White

world does not

mean learning

Mother Goose, but it does

mean literacy

and the ability to

speak to

and reason

with White men

who know no other

language

than English.

Eskimos need

the fundamental components

of a sound

White education

plus a depth knowledge

of Eskimo skills

and

culture, if they

are going to

be able

to deal effectively

with White men

and their schemes.

To

accomplish these

things

they need an

education to

become effective

Eskimos.

Eskimos

need intense

survival

training,

and they

need it right

now.

They must learn

to

survive

when a snowmobile

breaks down

in the vast

tundra wilderness

in mid-winter.

They also

need to survive

as competitors

with White men,

using

all

the modern skills,

so that

the Eskimo

people will be

assured a place

in the

Alaskan enterprise.

If their education

fails

these needs,

it is mis-education

of the most destructive

kind that can

only hasten

their departure

from the land

that is their

birthright.

GOALS

FOR ESKIMO EDUCATION

Goals

for what? Effective education?

On whose

terms are we

to evaluate?

And by

what criteria?

Margaret

Nick, Eskimo leader

from the

village of Nunapitchuk

on the

Kuskokwin,

framed

this dilemma

for Edward

Kennedy and

his Senate

Subcommittee

Hearings

on Native

Education in Fairbanks

in March

of

1969:

. .

.This last thing

I want

to say

I consider

the most

important

thing

in

education.

Let’s

ask ourselves

a question.

A very important

question.

What

does

education

mean? Who

knows the

answer? Maybe

there’s

somebody

in this room

who has a

degree in

education.

Maybe he

knows the

answer. I

don’t

know.

How can

I predict

how my

younger

brothers

and sisters

should

be

educated?

I’m sure my grandparents didn’t know what my mom and

dad would

have to encounter in life. He {they} didn’t know

how to

educate them. Just like I can’t predict how I should

educate

my children. I can’t predict how they should be educated,

but one

thing I know is, if my children are proud, if my children have

identity, if my children know who they are, they’ll be

able to

encounter anything in life. I think this is what education means.

Some people say that a man without education might as well

be dead.

I say, a man without identity, if a man doesn’t know

who he

is, he might as well be dead. This is why it’s a must

that we

include our history and our culture in our schools before we lose

it all. We’ve lost too much already. We have to move.

We all

know that Indian education should be improved and we’ve

got a lot

of ideas about how we should improve our Indian education. Now

that we have the information, let’s not kick it around

like a

hot potato. Let’s

take

the hot potato and open it before

it gets

cold (U.S. Congress 1969).

We must

focus on

concrete

purposes

of education

or we will

be unable

to

conclude

our study

functionally.

There

are

at least

four

objectives

involved

in the

fulfillment

of Indian

education

that we

feel

must be

considered.

-

The traditional

goal

of Native

education

as

pursued by missionaries

and

historically by the

BIA:

Is education

successfully

fitting

Eskimos

into

the

mainstream of American

life?

This

is

the

oldest

and

most

agreed-upon

goal,

and

is

an

adaptation

of

the

goal

of

American

education

at

large.

But

beyond

this

traditional

goal,

and

sometimes

in

contradiction

to

it, we see

three

other

emerging

goals

that

appear

essential

for

Native peoples

to

succeed in the

contemporary

environment:

-

The goal

of

human opportunity:

Does

education

fit

Eskimos to

meet

whatever

problems

life

presents

with

resources

and

resourcefulness?

- The

ecological-economic goal:

Does education

support and

equip Eskimos

to survive economically

in their Arctic

environment?

-

An emotional-health

goal: Does

education stabilize

and strengthen

Eskimo personality

so that

Eskimos can

stand the

stress of

life, as

all men

must, in

order to

survive in

the rapidly

changing world?

It

will clarify

our conclusions

if we

first

evaluate

these

basic

goals.

If

schools were

succeeding

in

fitting

Native

Americans

into

the

mainstream of American

life,

there

would

be

no

need

for

a

National

Study

of

American

Indian

Education. The

fact

is

that

attempts

to

reach

this

goal

have

been

largely

a failure.

Even

when

Indians

have

had

the

best

schooling

in

terms

of

White

education,

success

in

the

dominant

society

has

too

frequently

been

low.

The

special

problems

that

appear

to

exist

in

the

education

of

Indians-and

of

many

ethnically

different

minorities-have

largely

defeated

even

the

classical

goal

of

academic

education.

The

result

is

that

many

Indian

students

fail

to

master

fluency

in

English

and

fail

equally

to

meet

day-by-day

challenges

of

protocol

and

practical

survival

in

the

White

world.

We

should

speak

here

about

the

rationale

supporting

the

mainstream

approach. “Why

bother

to

educate

Eskimos

for

anything

other

than

entering

the

American

mainstream,

when

it

is

already

impossible

for

Eskimos

to

live

their

traditional

life?”

White

education

for

Natives,

whether

they

be

Eskimo

or

Navajo,

by

curriculum

assumes that

the

future

of

Native

peoples

is

in

urban

centers

of

wage-work

opportunity.

The

federal

government’s

recurring

termination

policies

for

Indian

lands

make

the

same

assumption.

I say,

the

Arctic

is

a fine

place

for

an

Eskimo

future,

as

much

as

it

seems

to

be

for

eager,

opportunistic

White

men.

With

balanced

economic

development

the

future

for

Eskimos

will

be

largely

in

Alaska,

and

therefore

they

should

be

educated

to

rake

advantage

of

this

future

if

they

so

desire.

The

continuation

of

Eskimo

identity

does

not

necessarily

require

living

in

a traditional

style,

though

for

many

it

might

mean

living

within

the

Arctic

ecology.

A

second

rationale

for

mainstream

education

is, “What

good

is

knowing

about

Eskimo

ways

for

a Native

who

will

live

in

Seattle?” In

terms

of

personality,

knowing

Eskimo

ways

has

nothing

necessarily

to

do

with

living

in

the

Arctic.

We

view

knowing

Eskimo

ways

as

knowing

about

self

and

building

a strong

identity

that

is

essential

even

for

the

Native

who

lives

in

Seattle.

Yazzie

Begay,

a

school

board

member

of

the

Navajo

Rough

Rock

School,

sums

up

this

issue

clearly:

We

need

education

for

our

children

so

they

can

hold

good

jobs

and

get

along

with

people

in

the

dominant

culture.

But

in

getting

this

education

they

must

not

forget

who

they

are

and

from

where

their

strength

comes

(Johnson

1968:150.)

Another

Navajo

leader,

Ned

Hatathali,

now

president

of

the

Navajo

Community

College

at

Many

Farms,

adds

to

this:

The

Navaho

people

must

re-discover

themselves

in

this

fast-moving

culture

of

today-they

must

know

where

they

came

from

and

who

they

are

in

order

to

know

where

they

are

going

(Johnson

1968:59).

We

present

a frame

of

reference

that

views

effectiveness

for

Natives

in

their

psychological,

as

well

as

their

practical

vocational,

skills

in

modern

life.

Our

three

further

educational

goals

are

related

to

educating

the

Eskimo

not

only

as

a practical

outer

man,

but

as

a

whole

and

resourceful

inner

man

as

well.

This

focuses

directly

on

this

study’s

conclusion

that

education

for

Natives

in

Alaska

is

detracting

from

the

goal

of

human

opportunity

rather

than

increasing

this

equality.

All

the

schools

make

a valiant

effort

to

teach

Eskimos

White

skills-

to

master

reading,

writing,

and

arithmetic-but

while

they

offer

these

learning

opportunities

with

one

hand,

they

undermine

the

relevance

of

these

attempts

with

the

other.

Thus

Eskimo

students,

instead

of

gaining

human

equality

through

education,

too

often

are

convinced

by

education

that

their

life

chances

are

unequal

simply

because

they

are

Eskimo,

and

nothing

rakes

place

in

White

schools

to

reinforce

their

confidence

that

being

Eskimo

is

a unique

opportunity

rather

than

a cultural,

ecological,

and

genetic

misfortune.

Equal

tools

do

not

necessarily

make

equal

men.

Equality

is

primarily

a psychological

reality.

Very

few

Eskimos

gain

an

improved

ecological-economic

position

through

education.

There

is

no

focus

in

schools

to

train

and

motivate

Eskimos

to

succeed

in

their

native

Alaska.

All

around

them

they

see

White

Americans

apparently

enthusiastic

about

their

own

futures

in

the

Arctic;

but

for

Eskimos

all

arrows

in

all

school

systems

point

south.

Generally

education

for

Eskimos

means

to

leave

their

environment,

which

is

then

rapidly

filled

by

White

men

who

gain

wealth from

the

same

environment.

In

all

schools

the

curriculum

is

void

even

of

appreciation

of

life

in

the

Arctic.

Hence

we

can

say

that

education

is

structured

so

as

to

empty

the

Arctic

of

adjusted,

successful

Eskimos,

since

the

focus

of

curriculum

is

to

make

them

dissatisfied

with

Arctic

life

by

stressing

values

that

can

be

obtained

only by

leaving.

As

for

the

emotional-health

goal,

it

might

be

said

that

missionary

schools

feel

they

are

educating

for

mental

health

by

bringing

Christianity

to

the

Eskimos.

Schools

in

general

feel

they

are

adding

to

mental

health

by

giving

youth

new

values

to

strive

for,

by

teaching

them

hygiene,

and

by

raising

the

style

of

Eskimo

living.

Bacteriological

hygiene,

higher

material

living

standards,

and

Christian

morality

are

dubious

approaches

to

health

of

the

spirit,

when

such

education

cuts

across

the

roots

of

Eskimo

personality.

The

most

generally

observed

effect

of

White

education

for

Native

peoples

is

that

it

usually

achieves

alienation.

Educators

should

be

aware

of

this

eventuality

and

try

to

give

back

as

much

as

they

inadvertently

take

away.

In

the

case

of

the

Eskimos,

this

balance

seems

not

forthcoming;

and

educated

Eskimos,

like

so

many

educated

Indians,

often

have

serious

personality

problems,

alcoholism,

and

high

suicide

rates.

Included

in

our

sample

is

just

one

example

of

a coordinated

sustained

effort

to

strengthen

students’ psychic

wellbeing.

This

was

the

example

of

the

students

from

the

bicultural

program

of

the

St.

Mary’s

Catholic

high

school.

These

visiting

students

appeared

to

have

durable

personalities

that

had

definitely

been

strengthened

within

education.

The

conflict

over

the

goals

of

education

is

no

special

fault

of

the

Native

schools.

It

is

the

basic

conflict

of

American

education

today.

But

we

feel

the

time

is

at

hand

when

attitudes

must

and

will

change.

And

the

most

important

change

will

come

in

schools.

Teachers

can be

trained

now

and

supported

in

changing

the

negative

course

of

education

not

only

for

Native

Americans

but

for

the

whole

range

of

ethnically

different

children.

Quite

possibly

this

change

will

take

place

first

in

the

inner

city,

before

it

affects

the

tundra.

The

challenge

is

not

new.

It

was

faced

in

the

New

Deal

for

Indians

under

Roosevelt.

The

effort

failed

then;

perhaps

it

was

too

diffuse,

too

romantic,

its

purpose

misunderstood

and

not

sustained.

We

feel

it

can

succeed

now.

INTO

THE

SHARED

FUTURE

OF

EDUCATION

The

Native

American

is

no

longer

alone

in

his

plight

of

education.

The

commonality

of

educational

default,

the

shared

problem

of

human

survival

in

this

industrial

age,

is

of

great

significance

to

the

solutions

of

Indian,

Eskimo,

and

Aleut

schooling.

Basically

the

problem

is

shared

by

Afro-American,

Spanish-American,

and

all

children,

even

White

children,

who

must

struggle

for

survival

in

personality

and

uniqueness

in

American

conformity.

The

chasm

we

find

in

the

Eskimo

classroom

is

found

in

the

inner

city

schools

of

our

major

cities.

The

chasm

is

there

in

the

Anchorage

city

schools

for

both

Native

and

White

students.

Facing

this

reality

can

bring

many

skills

to

Native

education

and

help

clarify

the

real

problems

in

Indian

schooling

because

it

is

a

larger problem.

If

we

were

able

to

understand

and

remedy

the

defects

in

Indian

education,

we

might

finally

be

at

the

core

of

a

significant

modern

education

for

everyone.

I

do not

feel

we

are

dealing

with

the

unique

survival

problem

of

an

Eskimo

personality,

but

with

a

shared

problem

of

personality

development

for

any

child.

The

goals

of

Eskimo

education

evaluated

in

this

conclusion

could

relate

to

the

success

of

any

American

classroom,

including

the

gatherings

in

colleges

and

universities

as

well.

I feel

the

revolution

of

education

has

been

taking

place

around

these

four

points.

Look

at

the

first

goal:

Is

education

successfully

fitting

the

student

into

the

mainstream

of

American

life? This

is

largely

the

historical

function

of

schools

and

still

is

the

major

goal

of

public

school

education.

This

refers

back

to

the “melting

pot” philosophy

of

Americanization

which

was

for

so

long

the

foundation

of

public

school

instruction

and

at

the

same

time

the

cause

of

some

of

the

serious

failures

in

education.

Compulsive

conformity

in

the

mainstream

sets

the

stage

for

inequality.

Students

already

in

the

mainstream

hold

superiority

over

those

who

must

give

up

their stream

to

become “Real

Americans.” In

terms

of

mental

health,

the “melting

pot” process

has

been

the

leveler

of

self

and

the

alienation

of

the

society.

There

are

thoughtful

teachers

who

look

on

the

mainstream

of

American

life

as

a threat

to

well-being,

rather

than

an

educational

accomplishment,

and

pluck

their

students

from

this

flood

for

a more

humane

destiny.

Are

White

schools

fitting

students

successfully

into

American

life?

Never

has

there

been

such

a high

dropout

rate

from

social

and

economic

functions.

Is

this

a fault

of

education?

Probably

it

is,

but

it

is

also

a failure

of

the

society

itself

to

offer

human

fulfillment

to

its

citizens.

We

are

in

a

cultural

upheaval;

burgeoning

awareness,

expectations,

and

self-determination

are

challenging

every

structure

of

American

life

in

search

of

new

fulfillments.

The

dilemma

of

human

need

creates

an

atmosphere

in

which

we

proceed

with

a haunting

feeling

that

education

has

failed.

Where?

In

the

classroom?

Is

this

the

failure

of

teachers?

In

part,

yes!

We

are

haunted

by

our

own

inabilities

to

respond

to

what

we

know

lies

outside

the

school

in

the

real

lives

of

our

students.

Should

this

not

be

a major

consideration

of

education?

There

is

certainly

the

awareness

that

education

is

not meeting

the

challenge

of

emerging

issues.

We

worry

about

Eskimo

students,

and

we

can

be

as

deeply

concerned

for

the

future

of

all

children

for

they

share

many

of

the

same

survival

dilemmas.

The

second

variable

in

our

evaluation-the

goal

of

human

opportunity-is

in

every

challenge

of

contemporary

education.

What

is

human

opportunity?

Is

it

making

$20,000

a year?

There

can

be

little

humanity

in

materially

powerful

success,

yet

the

drive

of

public

education

is

to

make

money

and

to

rise

to

a higher

level

by

making

more money.

What

human

opportunity

is

offered

the

Eskimo

child

in

the

White

school?

To

leave

his

village

and

succeed

financially

in

Anchorage

or

Seattle

in

a White

style?

This

is

the

central

goal

offered,

other

than

Christian

ethics,

Christianity,

reading,

writing,

arithmetic,

and

physical

hygiene.

I

would

presume

human

opportunity

for

an

Eskimo

would

be

to

excel

successfully

in

the

modern

world

as

an

Eskimo.

I believe

this

is

what

we

all

need

to

achieve

human

opportunity-to

excel

in

who

we

are

and

to

be

gratified

and

recognized

as

who

we

are.

Human

opportunity

can

be

economic,

but

it

is

also

an

intrinsic

accomplishment

in

which

humanity

is

the

key

to

gratification

and

success.

The

culturally

determined

St.

Mary’s

High

School

offered

its

students

this

gratification

in

building

on

the

self-esteem

of

the

Eskimo.

Do

we

offer

the

Afro-American

this

human

opportunity?

If

so,

to

what

extent?

What

about

the

people

of

Appalachia?

Where

in

our

school

system

are

students

obtaining

these

gratifications?

Only

in

the

limited

syndrome

where

teacher

and

students

relate

on

the

same

empathetic

plane

of

values,

where

otherwise

invisible

structures

of

culture

are

mutually

embraced.

Is

human

opportunity

and

potential

a

practical

goal

of

education?

It

could

be

if

the

needs

for

human

opportunity

were

defined

and

if

the

processes

of

reaching

these

goals

were

as

varied

as

the

children

in

each

classroom.

Economic

and

ecological

goals

of

learning

are

essential

in

retaining

our

human

relationships

to

our

environment.

Survival

for

Eskimos

is

deeply

involved

in

how

they

continue

to

relate

to

the

Arctic

ecology.

But

we

may

ask:

Is

the

Navajo

Reservation

being

strip-mined

for

fuel

through

the

failure

of

sound

economic

and

ecological

education?

Navajos

learn

little

in

BIA

schools

to

alert

their

leaders

to

the

ecological

suicide

of

selling

their

underground

power

resources

to

White

American

power

needs,

a scheme

which

will

destroy

millions

of

acres

of

grazing

land

and

deplete

an

already

dwindling

water

supply.

Every

Native

American

group

has

been

pillaged

by

this

same

greed.

Do

White

schools

teach

ecological

conservation?

Do

the

schools

in

New

Mexico

teach

Spanish

Americans

how

they

can

survive

on

their

own

lands?

Does

the

California

school

system

teach

the

value

of

recreational

space

and

the

survival

of

its

forests?

We

teach

about

economic

success

and

mastering

nature’s

resources

in

terms

of

dollars

and

board

feet.

Are

such

questions

now

confronting

the

Eskimo?

If

we

could

organize

learning

in

Eskimo

schools

for

survival

in

salmon

fishing

and

gathering

Native

foods,

we

could

design

social

studies

which

might

save

our

own

dwindling

open

space,

and

teach

ourselves

and

our

children

how

to

live

humanly

in

cities.

The

final

goal

for

evaluation-education

for

emotional

health-is

essential

for

Native

people’s

survival,

as

it

is

for

ours,

to

gain

an

appreciation

of

cultural

ways

so

that

we

all

may

retain

our

balance

in

modern

life.

Sophistication

and

appreciation

of

cultural

values

are

essential

to

anyone

for

making

wise

choices

in

acculturation.

What

should

be

kept,

what

should

be

modified,

and

what

can

be

given

away

without

loss,

all

determine

the

vitality

and

strength

of

Indian

or

Eskimo

groups

and

their

resilience

in

surviving

in

modern

technological

surroundings

that

can

destroy

them

as

people-as

it

is

destroying

the

diversity

of

our

dominant

society.

Do

public

school

social

studies

teach

toward

emotional

health

in

the

cities?

Do

social

studies

teach

ways

of

renewing

exhausted

psyches?

Is

the

present

social

and

economic

dropout

rate

and

alienation

the

result

of

the

failure

of

education

to

train

us

to

survive

in

what

has

come

to

be

an

unbearable

circumstance?

The

success

of

Indian

education

certainly

depends

on

cultural

and

emotional

survival

as

surely

as

it

does

for

White

students

who

must

learn

to

live

in

Chicago,

Detroit,

and

San

Francisco

as

adequately

as

on

the

cattle

ranges

of

Colorado.

The

critical

need

for

any

Indian

student

is

to

master

the

stress

of

modern

life

by

achieving

values

that

offer

personal

definition,

human

community,

gratification

from

work,

and

faith

in

his

own

integrity-these

are

the

needs

of

all

students.

So

in

this

final

sophistication,

the

Native

American

student

is

not

alone

in

his

mental

health

needs.

For

the

same

reason,

teachers

in

any

classroom

are

not

isolated

from

the

challenge

of

working

with

Indian

children,

for

the

accomplishment

is

basically

the

nurturing

and

developing

of

the

whole

child-every

child.

The

perspective

of

solutions

sketched

in

this

conclusion

are

of

two

dimensions-the

humanly

near

and

the

politically

far.

This

action

view

includes

changing

the

structures

that

perpetuate

negative

schooling,

and

politically

this

means

also

meeting

the

challenges

of

changing

the

society

that

so

many

schools

are

frantically

trying

to

preserve.

Certainly,

in

the

overall

view,

this

is

a long-range

revolution

that

frustrates

many

teachers

absorbed

in

their

daily

schoolroom

world.

What

can

he

or

she

do

to

even

change

the

administration

within

his

or

her

own

school?

On

short

terms,

possibly

nothing

beyond

the

voting

duties

of

a citizen.

Militant

teachers

too

frequently

turn

away

from

schools

because “you

can’t

teach

humanly

in

this

kind

of

a society.” The

view

we

are

dealing

with

here

is

out of

the

classroom

into

the

default

of

this

phase

of

history.

We

can

leave

the

classroom

and

enter

the

power

struggle,

or

as

frequently

we

can

succumb

to

numbing

withdrawal

that

stops

teachers

from

doing

even

what

little

they

can

do

in

their

own

classrooms.

There

can

be

another

focus

because

the

children

are

there.

If

we

shifted

our

view

into

the

individual

destiny

of

each

student,

what

could

a teacher

realistically

see

and

do

to

promote

whole

child

development?

As

a teacher

in

a

classroom

we

can

do

little

about

the

policy,

or

even

the

necessity,

of

sending

Eskimo

children

thousands

of

miles

away

to

finish

high

school,

yet

we

can

deal

with

this

reality

in

the

classroom.

How?

Empathetically

we

can

appreciate

the

personality

needs

of

the

students

who

must

make

the

educational

journey.

We

know

they

will

need

clear

identity.

We

know

they

will

need

great

resources

within

to

make

this

experience

positive.

The

Eskimo

students

setting

forth

need

what

all

our

children

need,

a strong

foundation

of

self

and

culture

to

stand

on.

In

some

fashion,

each

teacher

is

contributing

to

or negating

this

process,

perhaps concurrently doing

both!

The teacher has broad freedom

in

person-to-person learning

and

communication. On significant

levels,

education results from interpersonal

success

and this can be accomplished

even

in the midst of repressive administration.

This

writing touches

on many

self-fulfilling failures

between teachers

and students.

Most of

these failures

are culturally

imposed and

would be

there whether

administrations changed

or not.

These defaults

will remain

until we

learn to

equalize our

cultural stations

and minimize

the power

discrepancies of

ethnic discrimination.

Until this

happens teachers

and students

will remain

isolated by

the chasm

that divides

them, though

teachers will

go on

struggling to

reach across

the gulf

to the

different child.

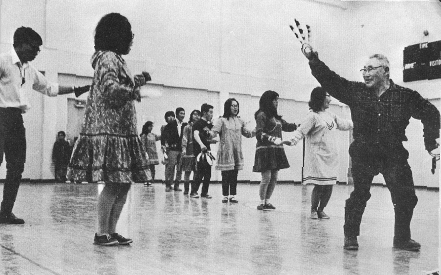

Visiting seniors from the bilingual and bicultural

St. Mary’s High School

on the Yukon dance for the students of Bethel’s Consolidated Elementary

and High School. A dancer from St. Mary’s village teaches and leads this

dance of Eskimo life.

|