|

Alaskan Eskimo Education:

A Film Analysis of Cultural

Confrontation in the Schools

5/The classrooms on

film

KWETHLUK, A PROGRESSIVE VILLAGE

“Kwethluk is different from Tuluksak. They’re very progressive

down there and busy. I think they have

had some fine teachers there,” observed

Mrs. Pilot in Tuluksak. Kwethluk is fifteen

air-minutes from Bethel. It is a large village with much involvement

with the outside world

and a number of career Eskimos working

at status jobs in Bethel. In a sense Kwethluk is success-oriented

and a village of cooperation.

Head Start: OEO (Funded by the Office

of Economic Opportunity)

Our first filming

was of the Head Start school, housed in a ramshackle planked

building of

spacious dimensions.

This

was

the council

house of Kwethluk and large enough

to seat the adult population. The

very setting made Head Start a village-dominated

enterprise, in which

there was much expressed community

pride. As a model it was a “Village

Community School,” serviced by

the community and taught by two young

Eskimo women of the community. Except

for a short summer

workshop in Fairbanks, the teachers’ education

was the same as that of many adults

who had also gone through the BIA high

school

programs at Mr. Edgecombe, Alaska or

Chemawa, Oregon. Realistically

it was a Native school taught by Native

teachers and a very valuable Opportunity

for observing the educational potential

of community

education.

The first visual impression

of the school interior was of its drabness

and very

limited equipment.

An oil barrel

converted

into a wood

stove gave meager heat. Long benches

and a bare table were the only furniture.

On one end was a walled closet area

holding supplies. Though the day was

overcast,

blinding light reflected

off the

March snow pack,

and the room was brilliantly lit.

Wearing

stretch pants, the two teachers, Miss Annie Eskimo and Miss Betty

Eskimo,

were warming

themselves

around

the stove when

a father

brought in his well-wrapped children

for their day at school. Parkas were

removed

and soon

the children

were

stomping

off the snow in

the anteroom and running eagerly

to join a group seated on boxes around

the teacher.

OEO Head Start class

in the village of Kwethluk, learning English from

a book

about Eskimo

children.

Watching the film silently

without its accompanying tape, one would

assume that

the teacher was

pursuing a very

culturally determined

curriculum, so shared and intense

is the listening. Actually the

curriculum was

the standard Mother

Goose! And the

mime gestures given in unison

were, we assume, standard kindergarten

material

taught

in any White school in America.

Indeed we filmed other Mother

Goose classes in BIA and state schools,

but

they were strikingly different

in

performance.

Here we observed

the most fluent nonverbal communication filmed

anywhere in our

study. From teacher to

student, from student

back to teacher,

and between student and student,

the class was synchronized

and wired together

on

one communication

circuit so

visible one could

see a

communication flow passing

through this unified educational group.

First, there was body communication.

Everyone was touching everyone

else. Time lapse

studies reveal

synchronization

of movement-leaning

forward, leaning backward,

holding forth a hand, rocking,

swaying

as one being,

intense eye-to-eye

communication,

messaging by

hand, touching, increasing

communication by

rearranging space.

For the children

this was home, not a school. And later in

free-play, clowning in adult

clothing, stalking about

in adult high pumps,

children moved easily and

fearlessly. But discipline was in evidence,

signaled

by a hand projected almost

wordlessly,

so that the morning passed

in a sense of

order

and

purpose.

There were ill children

and some upset children who were

tendered

positive

body affection

and led to

tasks by

the hand, sat down

at tables with a caress.

But in spirit children

were not

led but

motivated

to move on their own momentum.

A sick child was motivated

to join the art

session. Miss Annie

Eskimo demonstrated

the various

colors

possible with crayons,

and then let

the free-style drawing

of the child’s peers lead

the timid student in graphic

expression. Art work on

the walls was all free style-collages,

cutouts, and finger

paintings. Here was the only art

session filmed in Alaska

where children were not coloring

prepared Mother Goose dittoes.

Our team all rated

this class as outstanding. We

surmise

that three

circumstances

were involved in this

school’s

success. One, it was

by default underequipped,

which drew out special

initiative

from both teachers and

students. Two, direction

from above was very meager

but empathetic. Ida Nicori,

field representative

of the regional

Head Start office in

Bethel, was a Kwethluk girl, so

that the relationship

all around was one of trust.

The Head Start teachers

were free to

convert the experience

into their own language

and on their own terms.

Three, the two teachers,

with modest training,

did not feel themselves above the village;

rather they felt part of the village,

which changed

the conventional relationship

between teacher, students,

and parents.

I am sure

they fulfilled most of the ideal expectations

of

child

educators and the

ideal of higher education

courses in child

development, hut they

did this in response

to human function,

not to theory. Their confident

position

spontaneously

converted a hackneyed

and often deadly Mother

Goose

routine into

an Eskimo

storytelling episode.

The cultural self-determination

sensed nonverbally

was a determination of style,

pace,

and rhythm of

the Eskimo way,

which

might make

any curriculum palatable

to Native children.

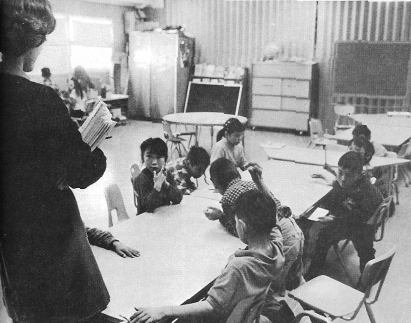

First grade in the BIA school in the village

of Kwethluk. Prefirst

in the BIA School

Two

hundred yards from the village Head Start,

Mr. Principal,

principal

of the

BIA school,

was instructing

a prefirst

class, also using

the curriculum of

Mother Goose. But the setting

is radically

changed. Mr. Principal

is teaching

this

class in the

absence of his wife,

who is away on a

medical leave.

Nowhere in America

will you find a more

modern,

well-lit,

and

well-equipped school

than the

BIA plant in Kwethluk.

It is

technologically perfect,

and painted in relaxing

pastel shades. But

Mr. Principal’s

large classroom is

also shared by the

second grade to accommodate

another loss in teaching

personnel.2 At

one end, second-graders

lean over their workbooks,

watched by the Eskimo

teacher’s aide,

who stands quietly

above the busy students,

occasionally leaning

down to help. At

the other end, Mr.

Principal is projecting

Mother Goose images

with an overhead

projector to a sprawling

class of prefirst

students who are

sitting on three

lines of low chairs.

Reading from

a paper, he firmly

singsongs the Mother

Goose rhymes with

his students, some

in rhythm, some not,

some looking about

the room, gazing

at

the big enlargement

of Little Bo Peep

who lost her sheep.

All-persuasive Mr.

Principal tries to

turn on his kids,

while they try to

sit still

and concentrate on

Little Bo Peep; indeed

everyone seems trying together.

The

film record shows

very fractured communication.

The teacher is

earnestly and clearly

projecting

the message,

but the

words barely

seem to make it over

the chasm to the

Eskimos. Reception

signals

are

low.

Eye reception

is equally low. Faces

were focusing

in all directions,

a few on the enlargement,

a few

on the

teacher.

Body

behavior was equally

distracted-feet flying

out in all directions,

some

students slumped,

some

sitting

straight,

bodies twisting,

leaning back, leaning

forward.

Mr. Principal’s

efforts seemed in

vain. Each child

was a distracted,

unreceptive, uncommunicative

individual,

until a National

Guard plane zoomed

down on the nearby

flying field-then

senses synchronized

and for a moment

half the class was

an intercommunicating

group.

We are here

observing the same

curriculum

but with

a major

difference. One,

the teacher is

a White

man and

a stranger,

who has only

been in the school

less than a year.

He has had

very little

contact

with

the villagers

except

in his classroom.

Two,

the teacher

was

standing while the

students were seated

in

rows. Spacially,

intercontact was

all but impossible. The row seating

disoriented the intergroup

communication that

might have been there

if the

children were sitting

on the floor in a

circle,

with Mr.

Principal as one

element of

this

human circle. The

result of this disorientation

made each child a

dislocated

unit,

and limp because

he was not in

a current

flow of

the group. Reception,

concentration,

and body control

rapidly ran out and

were replaced

with

dulling

preoccupation and

boredom. What

if the Eskimo aide

were to singsong

alone with

these

kids?

Would

the circumstance

have changed?

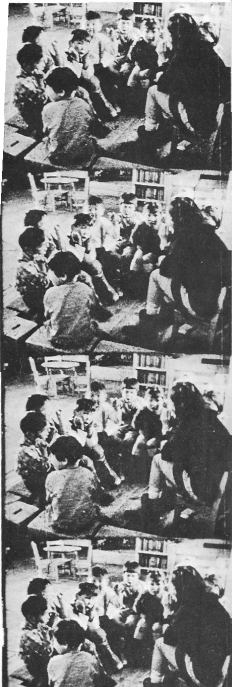

Teaching English by acting out Mother

Goose rhymes in the OEO Head Start class in Kwethluk. Film clip

illustrates body proximity and

sensual unity of children learning together in a circumstance typical

of a small-room culture, where living is usually within body reach

in the small dwelling of the Arctic.

The next session was an English language class based

on a supposedly practical situation.3 Written on the blackboard

in large letters:

Good morning Mr. Policeman.

My name is ____________ .

Good morning. Can I help you?

Can you direct me to the Hospital?

Yes, I can.

Thank you.

Is this a situation an Eskimo child might meet in the

streets of Anchorage? Mrs. Pilot in Tuluksak had an illuminated

stop-and-go

sign to alert children to survival in cities; Mr. Principal

had a standard educational tool-a cardboard image of a policeman

with

a

hole for the face to frame the head of the Eskimo child,

so each child could be Mr. Policeman. A martyr was drawn from the

group, his head thrust through the cardboard policeman image. Looking

sheepish, the martyr and another recruit repeated, reading

from the board, “Good

morning, Mr. Policeman. My name is John.” And so on

through the sequence. Then still another child was drawn

from the group to

say to the cardboard “Good morning, Mr. Policeman.”

Again

Mr. Principal used the greatest persuasion-physically standing

the children face to face. Turning to the group,

he enunciated

very distinctly and corrected their responses with gestures

of encouragement and criticism. Psychologically, when these

gestures are looked at frame for frame, they turn out not

to be gestures to draw communication together; rather they

seemed

to

be pushing

the children even further away.

We evaluate this class knowing

there was great stress in this school. Two teachers had left. It

was near the end

of a long

winter. Mr.

Principal was, no doubt, worried about his wife. I was

warned the school would be tense, and realistically I

had filmed

this tension

projected into the classroom, tension that was no doubt

widening further the gap already lying between school

and community.

We cannot dismiss this as an unusual circumstance, however,

for

all too frequently

there is stress in the compounds. This stress should

be expected, realistically, as one of the barriers that arise

between

isolated White teachers and the Arctic community.

Despite

the internal strife, the BIA school in Kwethluk held up remarkably

in dedication and educational skill.

The stress

of the

principal

substituting for his ill wife does not negate the effort

that he put into trying to make his school a success.

The performance

of

other Kwethluk teachers speaks for the goals of his

administration.

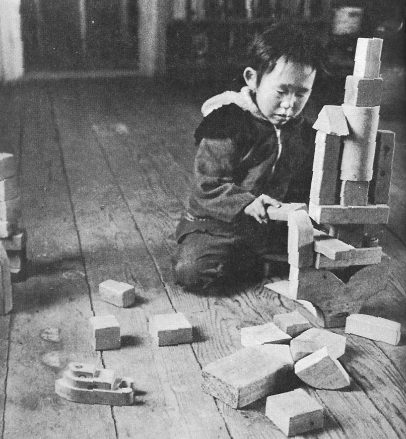

Head Start student in the village-run OEO school in Kwethluk. Home

and school are a step apart; learning here begins at the door of

the home. Lower

Grades: BIA

The first three grades and the eighth grade were taught

by Mrs. and Mr. Kwerh. Both received a high ranking

by the

research team. I believe they were equally isolated from

the village but were well-oriented and disciplined teachers.

Maybe

too disciplined,

but they did not break under the circumstance and kept their

classes on a high level; overdiscipline may have been a survival

essential.

First grade was taught along with second and third.

This demands programming. The classes were scattered about

the

room in groups,

some with workbooks, some with earphones listening to audio

lessons. First grade was gathered around a table with the

teacher. As

one researcher noted, “She camouflaged herself by sitting

low with her students.” The class was relaxed and not

teacher dominated. Communications from the teacher were directed

verbally to individuals

or to small groups, so that the room remained open for relaxed

student-to-student communication. Students felt free to get

up, look out the window,

talk to one another in a reasonable way Researchers agreed

it was a happy class and an open class.

Upper Grades: BIA

Across

the hall Mr. Kweth taught eighth grade. In many ways this

was an invaluable filming opportunity.

When

I set

up my camera, it appeared I would be recording a very rigid

situation-a multigrade class of sixth, seventh, and eighth

grade students

sitting compactly behind desks. Mr. Kweth took a teaching

position at the

head of this large class group, and because of the way the

seating was arranged, there seemed little opportunity but

to lecture.

And that was what Mr. Kweth proceeded to do, never once leaving

his

position or asking or accepting any response from the students.

Might this

be just the approach to turn off bewildered Eskimo students?

But Mr. Kweth was not only a good lecturer; he had chosen

what turned out to he a swinging subject-mental health-with

a heavy

accent on

the deprivations of life in the “Lower Forty-Eight.”

On

film can be seen the effect of relevance. As one

researcher noted, “Mental

health is ego-oriented.” This must be true, for here

was the longest concentration span of any class

in our sample. Despite

a

fairly dry delivery, the class rarely took their eyes from

the teacher except to make notes. The level of intellectual

intensity

cannot

he matched by any high school class I filmed in Bethel or

Anchorage. The teacher proceeded to diagram the health of

Kwethluk village,

showed the whole world related to Kwethluk, and stressed

the importance of family, village cooperation, and positive

human relationships.

Apparently this found sophisticated ears

and may have touched the mainsprings of village vitality.

Communication within

the group

was intense. Reception was visually clear from ear to eye

to notebook, and there was free intergroup communication.

Notes

were compared,

books were shared (a social studies text around which the

lecture was composed), and the student-to-student communication

was

about the lesson, either sharing notes or audio and body

communications while eyes were clearly focused on the teacher.

In

Kwethluk there were two amazing extremes: first, communication

and empathy converting an irrelevant curriculum into an exciting

experience in Head Start, and second, a highly motivating

and relevant curriculum turning on Eskimo students despite

a dull

and exhausting

teaching method-the lecture. I do not suppose Mr. Kweth

has this good circumstance of relevance every day, but this day

was the positive record of what can take place when Eskimo

children

relate

to the message.

Middle Grades: BIA

Later I filmed fourth

and fifth grades taught by Mr. Luk, and by combining relatedness,

clear

two-way communication,

and relevance, Mr. Luk had one of the happiest classes

in the BIA sample. Only one White teacher in the regular

classes

rated

higher

in terms of communication.

What was involved in Mr. Luk’s

class? First in importance was a great diversity in communication,

on the part of the teacher and

in return, on the part of the students. Mr. Luk used

clear verbal communication, explicit nonverbal hand,

body, and arm signaling,

and he constantly changed, adjusting himself in space

to improve and complete communication. He would move

from the front of the class

directly to a respondent, lean over and speak personally

with this student. Other times he directed himself to

small groups. Then he

would communicate with the class at large. Students freely

approached him, drew him to their problems, or helped

themselves to materials

when they needed them. Mr. Luk switched from verbal to

visual techniques rapidly-pointing to the clock or moving

hands on a demonstration

clock, drawing a foot on the hoard and relating it to

the student’s

foot.

Students worked intensely, writing, reading, computing,

working at the chalkboard with visible enthusiasm. This

high spirit

was expressed in communicating with each other, by body

relating, eye signaling, and work sharing. When tension

got too high

for

some

students,

they downed and fooled around, yet were not pounced on

by the teacher. In body motion there were no signals

of boredom

or

sleepiness and

many body signals projected work involvement, such as

body bending intently over work or moving to improve

reception

from the teacher.

There was a fire drill. The school poured

out into the yard. And then an allrlear. The whole class ran spiritedly

back

to the

classroom as if eager to continue their projects.

Around

the walls were large art drawings, made by the students, of the

history of ancient civilizations,

including the

Aztecs and Mayas.

One felt Mr. Luk had a lively imagination and driving

educational interests that were projected to the

students.

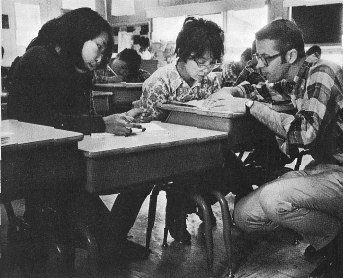

Dedicated, well-trained teachers put great effort into their task.

A sixth grade teacher in a BIA village school.

Tuluksak and Kwethluk BIA Schools Compared

There is a temptation

to compare the Tuluksak with the Kwethluk BIA school. The comparison

is not

easy to make

in terms of

educational skill and dedication. All the teachers

at Kwethluk were in their

first year of reaching in the Arctic. They were

from a different generation-knew more on one hand and

much less on another

in terms of the long-range development of Native

potential in

the Arctic.

Educationally this worked in favor of the Kwethluk

school, for lack

of self-fulfilling knowledge about Eskimos allowed

them to work ideally and put out units of energy

that would

be unrealistic

for old Alaska

hands. Mr. and Mrs. Pilot had been twenty years

watching the ebb and flow of the BIA. If they were not cynical,

they certainly

were

philosophical about the realistic limitations of

village schooling. They each had a rich fund of

historical

knowledge and years

of

living with the benign failure of the BIA. Their

very

insight into history

and the Eskimos seemed to temper their efforts

and had the effect of quietly limiting the scope of their

teaching to

what they

perceived as reality.

The Kwethluk staff have scattered

now. Two, I believe, are still in the Arctic. But

the Pilots are still

in Tuluksak, no more

disillusioned than they were in the spring of 1969,

giving the same warmth and

day-by-day generosities to their village.

The Moravian

Children’s Home, Near Kwethluk

The Moravian Home and School is just three

miles from busy Kwethluk, but years away in time and

culture. There is

little to compare

between the BIA school and this mission project.

Issues

of change hardly

stir the Home, other than shifting from dog team

to gasoline snowmobile to fetch the mail in winter.

I

cannot imagine

that any change has

come to its classrooms for the last twenty years.

One of the teachers is the daughter of an early

Moravian missionary

couple

who raised

their family on the Kuskokwim. She teaches fifth

through

eighth grades. Kwethluk Eskimos speak with respect

of this school-tough

training,

high standards, no games.

The research team had

only negative comments on the first- to fourth-grade class. The school is,

of course,

frugal

and poorly

equipped, but

this did not explain the totally drab, brown-on-brown

interior of this small classroom, where very young

children come

to learn. The

teacher was friendly but inept, and seemed unable

to reach her young students. They sat dutifully,

some

yawning, all

trained to look occupied,

though none of the research ream felt they were.

The film clearly showed that they were simply acting

busy.

They

sat reasonably

still, but their eyes were not focused on books

or on the speaking teacher.

Their focus was dead, nondirective, and sleepy.

There was a lot

of fidgeting, but always within a safe level so

that they still appeared to be attending the lesson.

The teacher was tethered

to her desk and made only short forays out, snapping back as if on a rubber

band, as

if this tiny

class were

threatening. One data sheet reads, “Maybe

just letting time pass.” Professionally she

appeared as just an unmotivated and poorly trained,

or possibly

untrained, White, middle-class

teacher.

Communication was superverbal with almost no other

expressions by arm, body, smile, or eye contact.

Only

one student seemed absorbed; he was leafing through

a book about Eskimos. The class text was

the usual

dreary White

boy-and-girl

story,

and there was simply nothing in the room to remind

the viewer that this school was completely surrounded

by

the white Arctic

winter.

The second class, fifth through eighth,

was held in a large but desk-crowded room. The effect of

the room

was

more

brown-on-brown, with an American

flag, a piano, a few religious pictures, and odd

decorations like cutout bunnies that in no way

related to each

other. The room,

like the rest of the Home, was anti-aesthetic but

clean, well-scrubbed, varnished and waxed. Twenty-five

students,

boys and girls,

worked

at their desks. A few showed signs of stress, as

one might expect in a home for displaced children.

Many

more were

relaxed and

looked genuinely happy.

The research ream felt that

this missionary teacher and her students were closer together than most

students and teachers

in the BIA

schools. They felt the teacher was quite secure

with her students and that

the room had a relaxed trusting air. The teacher

communicated verbally, with only a few nonverbal

arm signals, and

freely drew upon students

to act out lessons for the class. Students were

receptive to the teacher, and thus one form of

education was

happening

in

this school.

There was communication in this room, even though

it was basically one way. Students did get her

messages, listening

was real,

attention spans were reasonably long. Unquestionably

much education could take place in this room. In fact the Moravian Home

as an institution has

this rich potential. If it fails, then the fault

is

purely philosophical.

“Provincial” would describe the style of the Moravian Home,

and the relating was definitely family oriented,

as if everyone genuinely depended on one another. The quality of

education sprang

from this

and set the character of the school apart from

the BIA, where the teachers only needed the students to teach and

the students needed

the school only so long as they sat there. Here

there was no gulf between school and community because the community

was the school.

2 The BIA school at Kwethluk was filmed on two

field trips. On both occasions classes were very disturbed by the

loss of two teachers and the consequent efforts to combine classes.

Hence our records overlap the grade levels, but with different combinations

on the two visits.

3 I have been told since that the policeman lesson

was drawn from a TESL (Teaching English as a Second Language) program

prepared for Spanish-speaking Puerto Rican children in New York City;

as such it makes more sense, both in regard to situation and linguistics,

since the rather stilted “direct me” makes use of the

Spanish cognate “dirigirme.”

|