|

Alaskan Eskimo Education:

A Film Analysis of Cultural

Confrontation in the Schools

4/Observations on

the held experience

THE PHOTOGRAPHER

AS PARTICIPANT OBSERVER

The act of taking pictures is a complete

experience in itself, just as the making of a survey, apart from

its data, reveals

many aspects of the field circumstance.

My first impression was

that teachers and principals are much more prepared to answer questions

than to appear before the camera.

The verbal examination can be more controlled and directed

by the

informant

toward a desired impression. Question answering is often from

an armored position and therefore tolerable.

The nonverbal examination

is harder to control, especially if it goes on continuously. Hence

schools are at first agitated

over

the request to film them. “Why?,” “What

for? ,” “Who

will see the film?” are immediate queries that must

be answered. But once such hurdles had been crossed, 90 percent

of the teachers

were relaxed and pretty much ignored my presence in their

rooms.

I am not saying they forgot that I was there. Rather, each

teacher is so programmed in behavior that during an hour’s

visit it seemed difficult, or even psychologically impossible,

to change his

pattern fundamentally. Hence poor teachers continued on their

negative programs, and good teachers continued turning students

on in a relaxed

way that made me feel unseen.

Every student seemed familiar

with photography and film, and they often showed a keen interest

in the process. They

were

allowed to look through the camera and to ask questions.

But they, too,

settled

rapidly into an established classroom pattern of being teacher-bored,

sleepy, distracted, or interacting with excitement to the

lesson. My presence in all but a few cases seemed neither to add

nor to distract.

Maybe this is a quality of film,

for it

flows

on with time, on the same time river that is carrying the

students to

freedom at the class’s end. The still camera takes

a slice out of time, and can both interrupt and

distort behavior for this

reason.

Working through the superintendent of the State of

Alaska’s

Consolidated Elementary and High School in the tundra city

of Bethel was a very different circumstance from visiting

isolated BIA

village schools. The state school superintendent was verbally

concerned about how his teachers would respond to the filming,

but bureaucratically

he was in control of their cooperation, and with varying

degrees of interest the teachers dutifully collaborated.

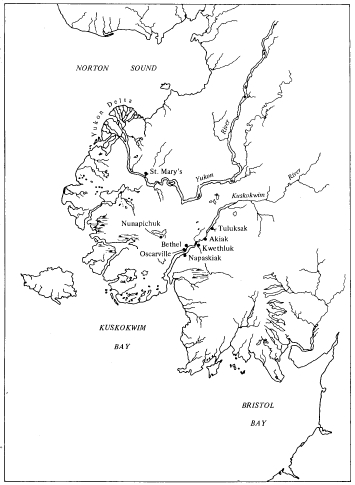

Location of villages in the Kuskokwim Basin.

To work in the village

school was at the prerogative of the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ director

of education for the Kuskokwim schools. In some ways my request

for film observation was more threatening

to the BIA than to the state school system. Once the Bethel

superintendent adjusted to my presence and to the observations

of Connelly and the

Barnhardts, he was enthusiastically opportunistic, for he

recognized that we wished a complete and honest picture that might

realistically benefit the school. After a month

he saw us,

in a sense, as collaborators rather than as spies. The state

school system is expanding rapidly in Alaska and is success-oriented.

The BIA school system is shrinking, is under attack, and

therefore is

extremely sensitive to any observation.

A major anxiety suggested

by the BIA superintendent as to why filming would be difficult

was the predictable tension

in the

isolated

schools. I was told that the teachers did not welcome visitors

(contrary to

the human assumption that they would like a break in their

monotony) and that they were usually too harassed and busy

with school

affairs to be able to work with a visitor. I was given the

impression that

thousands of miles out on the tundra wastes teachers were

harassed by hostile or wasteful studies, and therefore not

always hospitable.

Further, and of course logically, there simply were no accommodations

except in the teachers’ own homes. Indeed, everything

is short in the wilderness. Supplies of all kinds must be

purchased a

year ahead. Because teachers are apparently besieged with

senators and educators making surveys, the usual Anchorage

prices should be

paid for hospitality-$15 a night and $3 a meal were permissible

prices for visiting observers. Yet each teacher accommodated

visitors on his own terms-humanly established between teacher

and fieldworker.

The area director was sincerely concerned

about the psychological welfare of his field staff. Talking

things over in a cement

radar personnel site converted to a BIA nerve center of welfare

and

education, I got the message that life in the remote village

school was a

hazardous assignment and the turnover of personnel high.

Nothing must happen

that would upset the precarious equilibrium of the isolated

teachers. I left by bush plane for the villages with the

feeling that I

was entering an explosive assignment.

Location of villages in the Kukokwim Basin.

ISOLATION AND SURVIVAL

CULTURE

The Kuskokwim Basin in winter appears as coils of

frozen waterways

and lakes fringed with stunted black spruce and willows.

In the sourheast

there are glistening mountains, but west and north the tundra

wastes

slope to the horizon. In this vastness, a village is sighted

close to waterways-a scattering of cabins, a shimmering metallic

school

compound, a National Guard Quonset hut. Villages can be 15,

30, or 40 air-minutes from Bethel, 8 hours or 24 hours by

dog sled,

2 or

4 hours by gasoline-driven snowmobile.

Villages range in size

from 50 to 250 Eskimos, who only a few years ago lived off the

wilderness-salmon fishing and

berry

picking in

summer; rabbit snaring, deer, elk, and moose hunting, and

fur trapping in winter. The salmon still remain a major

foundation, but old-age

pensions, relief, and National Guard stipends have become

the

economic way of life, especially through the long winters.

Every year fewer

Eskimos endure the rigors of the winter hunting camps and

beaver trap lines.

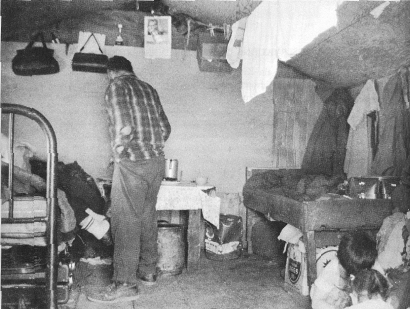

Home of a middle income family in Tuluksak.

As the bush

plane skims over the river ice low between river banks, one’s

first impression is that public health has come to the Arctic,

for the most imposing structures are the multitudes of neatly

painted white outhouses. The second impression is of

the barking sled dogs staked our by the privies and then of the

Eskimos who gather

to watch the mail plane skid to a halt below the diminutive

village post office. The mail sled skids down the bank, pushed

by laughing

children followed by elders, some dressed in Army high-altitude

flying gear, others in traditional wolf-fringed parkas. The Eskimos

like

visitors. They are amused and curious about strangers

and eager to make them welcome-a normal response, we humanly assume,

to life in

great isolation. Travelers have always agreed that

Eskimos are very sociable folk.

I have observed, on the contrary,

that White people of

status (and most White people come with status) dropped

on contract

assignments

into the moist, green isolation of tropical jungles

or dropped into the white isolation of the Arctic, often

respond to

the circumstance by creating further isolation by walling

themselves

off both

from the ecology and from the Native humanity around

them.

White schoolteachers in Native schools face this

dilemma. Some of the walls that rise around them are self-fulfilling

conflicts

of-

culture, strengthened by the bureaucratic and technological

zeal of a government agency. By White standards Eskimo

villages are

pitifully poor, unhygienic, and shockingly overcrowded,

often with two families

jammed into one small log cabin 15 feet by 25. As

in any survival economy, per capita income would be far

below

even the conventional

poverty line if relief and government succor were

removed.

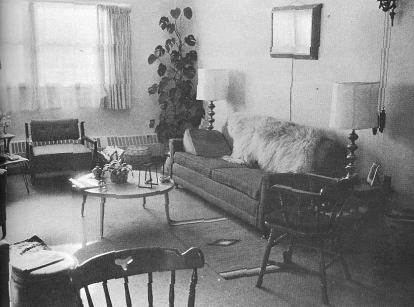

School teachers’ home in the BIA school compound

in Tuluksak.

Abruptly, in the midst of all this apparent squalor

and staked-out sled dogs stands the BIA school

compound. Its life pulse

is its diesel light plant, which makes the compound

a

mecca of

blazing

illumination

in the darkness of the village. (Two villages now

have their own light plants.) By day the BIA buildings

shimmer

in aluminum

and

fresh paint. Nothing has been spared to make these

units ideal models of

White mastery, technology, and comfort. On the

one hand, the excellence of the buildings speaks for

the drive

of the curriculum;

on the

other, the technology and comforts are essential

for the emotional well-being

of the staff. The comfortable life style of the

teachers’ home

culture is imported, indeed refined upon, to make

life tolerable in the Arctic isolation.

I am sure these comforts

do make life tolerable on one level, but on another they greatly

increase

the

isolation.

Teachers

exist

within this comfort style and rarely go outside

its walls-except to hunt,

which is the one ecologically oriented outlet for

male teachers in the villages.

To live within such

small space requires great skills in self-fulfillment and high

tolerance to

human shortcomings.

The shock of the

circumstance, too, often weakens both these skills.

Marriages crack, and contracts

are broken. The one skill that most field personnel

develop highly is the skill of keeping busy.

Fortunately the

bureaucracy

of

the BIA cooperates in this, for if all the forms

and receipts are filled our regularly, if radio

communications are kept

and duly

logged, there is literally little time for any

other activity. But the busy-ness

becomes another wall of isolation not only from

the community and the ecology but also from wanting

to

have visitors

observing their

operations. Indeed, once inside the educational

compound, it is difficult to set up after-school

interviews

with

teachers; they

are too busy

or they are exhausted.

Behind this inaccessibility

there are, of course, other real challenges of individual survival.

Quite realistically,

to

keep air space

and peace within the limited and nigh impenetrable

walls of the compound

(winter temperatures hover for days at 50 below

zero), personal privacy must be religiously

respected. Under

the stress and

multiple culture

shock, holding together as a person in this

isolation is indeed a challenge. Too often self-survival

is sought with

introversion

and

further imposed isolations that resent the

arrival of strangers.

Well-being anywhere is obtained in a complex

scheme of resources. When Eskimos move to San

Francisco,

this struggle

for adjustment

can be viewed in reverse. One Eskimo we observed

in Oakland was unable to transplant himself.

He worked, came home,

sat in a

compulsively neat but empty house, with no

ties with the surrounding community,

and drank himself into a psychiatric disaster

that required that he be shipped back to the

Arctic.

Clearly the success

of such

transplants depends on the ability to transport

sufficient life style so that

minimal wellbeing can be retained. When a familiar

diet is broken and new foods rejected, a “crack-up” in

personality can take place. For most teachers

a contract in the Arctic is an abrupt

interruption of normal life that will not begin

again until they return to the “Lower

Forty-Eight.” This is as true among

teachers in the state system at Bethel as in

the village schools of the BIA. Busy-ness is

an anesthetic that certainly helps many

through the Arctic winter. But this tends to

be a frantic solution unless other outlets

and relationships are achieved.

RELATING TO

THE

ARCTIC

The primary basis on which many teachers

relate to the Arctic is linked to their reason

for deciding to come to work with the Eskimos

in the first place. Some come for adventure,

but others come our

of a real concern for the advertised deprivation

of the Eskimo. The well-fed hold out a hand

to the hungry. Modern man brings aid to

primitive peoples-a missionary zeal that contains

empathy but also a severe sense of inequality.

They come north to help the Eskimo.

Few come north to learn. And, too, many others

come north for the money. Again, this is a

general view of White teachers in the Arctic.

The

motivated teachers of Eskimos approach their tasks with enthusiasm.

But as the year

passes,

enthusiasm may too often

change to a

fatalism about the hopelessness of the task

of educating the Eskimo within

his life and habitat. For many the very cultural

style

of their students’ families

is a block against education. Villagers can

appear to lack progressive motivation. Indeed,

Eskimos can appear lazy and improvident because

they often do not find White goals of much

value. For too many motivated

teachers the year’s contract ends in

negative discouragement.

The adventure-oriented

teacher, usually male, often does relate

to Eskimo survival skills

in hunting

and fishing.

Alaska is

a man’s

world, and though sports-oriented teachers

retain-well-being, their solution is usually

outside the village and does not necessarily

direct their reaching. Nor does it occur

to them to adjust school-attendance

scheduling so that Eskimo children could

learn these skills also. Other Arctic-oriented

teachers become collectors-Eskimo masks,

mukluks,

valuable furs, and exquisite parkas. But

this interest in Eskimo artifacts, again,

does not necessarily reach out to the Eskimo

villagers

or weave into classroom activity in terms

of a culturally involved curriculum.

The few

career teachers who stay for many years in

the Arctic are the exception. For

these

unusual people

school

busy-ness

may

be replaced by deeper involvements. Real

friendships are formed in the villages. Individual

teachers

in the past

have been

very influential

in developing cooperatives and starting light

plants in the villages. These lasting teachers

are not

so driven. On film

they appear

relaxed and generally live a human leisurely

pattern.

One such teacher is a pilot, owns

his own plane, and visits up and down the Kuskokwim.

His wife

is adept

in first aid

and generously

directs an Eskimo village health worker.

A circumstance that may be a key to their “lasting” is

their philosophical view of their jobs.

Generally they keep educational goals low,

or “real,” in

keeping with their aspirations for the

Eskimo villagers. This view can become

a fatalism,

reinforced by years of experience, that

closes the door on radical innovation.

This philosophical

view allows them

genuinely to like the Eskimos, but at the

same time precludes their envisioning anything

but a limited horizon for these villagers

unless

they leave. These teachers have another

great value: they stay, which is in itself

educational.

They have been a stimulation to students

to reach the goals they feel are practical

and progressive for the Eskimo. But it

is precisely because of goals of this nature

that

American Indian education is now under

grave

question.

These observations are not directed

solely toward a special BIA culture, but

as stated

earlier,

toward White people

contracted to work in

wilderness isolation. The State of Alaska

is taking more and more of the schools

over from

the BIA,

and it is

hard to imagine

that

circumstances would be radically different

for state teachers. Basically I am describing

the

teacher environment

of isolated

Eskimo schools

taught by culturally different White teachers.

My observations

are directed toward how this compound culture

affects education. Furthermore,

I am not describing a situation that is

wholly predestined and

not subject to change; indeed if it were,

the substance of this report would be futile.

ESKIMO

CHILDREN

Eskimo

children must be

the most rewarding

kids in the world to teach. This is one’s

immediate response to any Eskimo classroom

in an isolated village. There is enough

Eskimo

life style left to retain the traditional

personality. Will this change if the survival

culture of the Arctic environment is radically

eroded by intrusive technology and dollars

for work unrelated to

the ecology? As of now, the Eskimo children

are remarkably stable and optimistic, eager

for innovation and knowledge of the world.

One

rarely meets dour looks or difficult dispositions

in the elementary grades.

Poor teaching skills

and dull curriculum

are yet not enough

to dampen their spontaneity. They are apparently

easy to lead

and very cooperative. We have records of

teachers who have capitalized on this opportunity;

but

in general,

teachers

in the villages

make

instruction hard work, apply themselves

with compulsive intensity, and appear exhausted

after a class period.

You sense how

hard it is for them to reach over to the

Eskimo children from their

own

isolation. They appeared to be shouting

lessons

over a great gulf-and in

the film there was considerable air distance

as well as emotional distance between teachers

and

pupils.

Generally instruction was highly

verbal with little feedback from the students.

They sat

dutifully in class, amazingly

intent upon

the teachers’ words or else quietly

squirming, yawning, and stretching. Was

this because of a language block? Was their

English

even more limited than the teachers realized?

Would they have communicated in Eskimo?

Or did the teaching style limit verbal

feedback?

SCHOOLS

AND VILLAGES

The Bureau of Indian Affairs

Compound

The total presence of the BIA school-its

compound, staff, and technology-provides

its educational

impact on the

village. As observed, the school

plant is model of White perfection

which constantly contrasts with the

tattered and weather-beaten Eskimo

habitations. Each school has its maintenance workshop

and ultramodern diesel light

plant

that

runs

continuously. Each school has a kitchen

and a multipurpose room where hot lunches

are

served or bingo games

held for the village

on special

evenings. The kitchen staff members

wear uniforms and waitress-type hats and observe

ultrahygienic

routines.

The children’s lives

are spent running to the brightly lighted,

windowed school with all its technology,

and back home again over the snow or

mud to small, dark, not too hygienic

Native homes.

The educational staff

of the village school is not limited to White teachers.

Each

school has

an Eskimo

teacher’s aide and one,

or sometimes as many as three, Eskimo

maintenance and janitorial assistants,

and an Eskimo kitchen staff. The

Native staff members

are elite villagers, skilled in White

ways and considered intelligent and

dependable. Also these Eskimo staff

jobs may be the few cash

opportunities available in the village

and give the holders high status

roles in the community.

The educational

role of the teacher’s aide

is clear. Occasionally she sits down

with a group of children in the lower

grades and corrects

their spelling or math. A lot of

the time she stands, far away from

the teacher, and waits for an order

or a chance to be of service-finding

the pointer, the chalk, the blackboard

eraser or handing our dittoed forms

to students. Even in these modest

services I am sure these

aides are invaluable, if only for

their ability to put the children

at ease in Eskimo. What other educational

functions these young women could

be put to is a question to be examined

later in our text.

The educational

role of the various male Eskimo assistants

is considerably

more

vague. Whatever

their influence

is, it is benign

and most

informal. As stared, they are highly

selected personnel, educated in technology

and adequate, if not fluent, in reading

and writing. They are usually village

leaders

and belong to

the National Guard. Could

they be

used to teach industrial arts and

practical education and

to be rewarding

adult figures of educational success?

In a related way, what further educational

role

could the

kitchen staff

offer the

school?

A Village OEO Head Start

In the village of Kwethluk,

a few hundred yards from the BIA compound,

there

is a contrasting school culture,

the

Head Start

program financed

by the Office of Economic Opportunity.

For the Eskimos this is the village

school, and

the BIA

is the government

school.

The village Head Start

class is held in the commodious planked

council

chamber of the

village, and every

service of this

school is

carried out by the

village, including the

instruction. Two young women

of

the village with BIA high

school education and a summer’s

workshop in Fairbanks teach

5-year-old Eskimo children

rhe rudiments

of Mother Goose, English, and

alphabet recognition. I suspect

the class is far ahead of where

early childhood education is

supposed

to be, but this village school

is taught by alert and ambitious

Eskimo women with a high regard

for their pupils.

The OEO Head

Start program is directed from

Bethel by

a traveling

director,

herself an

Eskimo from

this very

village,

who flies

a circuit of village schools

80 miles in all directions

from Bethel.

Most of

the time the young teachers

are on

their own, and so the school

operates on its

own level.

The principal at

the neighboring BIA school was suspicious that

all they

did was in

Eskimo, but

when I played

him a tape from

Head Start

he was amazed and impressed

by the school’s effectiveness

in teaching English.

Viewed

on film the school is very different

from the BIA,

and it

is clear why this

school made

such progress.

In

the BIA

prefirst as well as in the

kindergarten at Bethel, there

is a great deal

of space between pupils and

teachers. In this Head Start

class, communication

is body to body, and there

is a current of communication

running

from teacher

to

students

and back to

teacher. The effect of

this communication is clearly

seen

on film.

The BIA teachers

are White and come and go.

The Head

Start teachers

are

kin to

most of

the children.

Though

English

is used heavily

in Head Start, it is easy

to lapse into Eskimo whenever

appropriate. This Head

Start class

was our one model

of the effectiveness

of Native

teachers with minimal teacher

training.

This circumstance will be

examined

again in our

conclusions.

A Moravian Mission

Home and School

A variation from the school

compound culture was the

world of the

Moravian Children’s

Home three miles from Kwethluk.

The Home was established

originally to accommodate

Eskimo children from families

stricken by tuberculosis.

Now that TB is no longer

the scourge that

it was, the Home is for

any child who needs care

and education. A church

and three commodious two-story

lodges are strung through

a

clearing in the stunted

spruce on a bend of a tributary

of the Kuskokwim. Through

the summer, boats and barges

stop at the Home, while

in winter,

planes land on the ice,

and dog sled and Sno-Go

link the Home with the

post office downstream

in Kwethluk.

Isolation is

nearly complete, except

for daily contact

with the Home’s

Eskimo population. Here

there is no village nor

any opportunity to interact

with the ecology except

to be surrounded by it.

Whereas

in the villages the school

hours tend to be culturally

separated from Native life,

here you find the school

one large family with

intense interaction between

everyone around the clock.

The

missionary commitment of

Moravian personnel makes

for

continuity.

It is a way of life,

and many stay

to retirement.

The religious

activity largely takes

care of well-being and

insists

on at

least an outwardly

loving social relationship.

As a missionary center,

both the

Children’s

Home and school are relaxed.

The children seem spontaneously

happy, and most of the

human problems met in the

compounds are solved by

the Moravian culture of

the Home. I am sure not

all missionary schools

achieve this relative harmony,

and it is a question just

what this Home offers in

functioning education for

Eskimos.

There is no overt

culture conflict simply

because

the children

are lifted totally

from their

own culture and submerged

in the school.

The extreme isolation makes

everyone functionally dependent

on everyone else. By comparison

the BIA schools are in

the mainstream

of Arctic

travel. Mail planes stop

twice a

week, and all day long

bush planes are roaring

in and

our.

The daily

radio “skid” from

Bethel holds each school

in the bureaucracy. But

the Moravian Home is “unto

itself.”

Compared

to the BIA schools, education

at the Home is

limited to the three

R’s and vocational

training such as typing.

The plant is poor but stable,

unequipped but severely

thorough.

The school appeared

to welcome visitors, and

the

director

was eager to talk

over the psychological

problems of

its charges.

The question

arises: Can such a mission

school innovate to the

bicultural needs of its

students? Moravian missionaries

initially

took a very

hostile view of Eskimo

culture, and the summer

school for

Eskimo village

lay

readers still

instructs against

Eskimo

culture

in the form of dancing

or traditional social life.

Religious attendance

in one village was fanatically

compulsive, and the church

program appeared not

to concern itself

with

the survival

problems of

the community, such as

building

a cooperative, encouraging

Arctic skill,

and so on.

One gets the impression

that even here in the

human warmth of the Home,

orientation is out of the

Arctic. The general

education offered is in

conflict with the life

style of even

the contemporary Eskimo.

Looking our from the Home,

the villages

hardly

exist.

On the

other hand,

Bethlehem, Pennsylvania,

seat of the

Moravian church, is critically

in focus.

THE TUNDRA CITY

OF BETHEL

What

kind

of education do Eskimos

receive from

this busy hub

of the Arctic? The school

in Bethel is excellent

as measured

in

White values-as

are the BIA village schools,

as

well. But here the school

is an appendage

of the

city, Bethel.

Bethel as

a school for Eskimos might be compared

to Gallup,

N.M., as a

school far

Navajos.

A liquor store

pays the

town’s upkeep.

And even though almost

everyone agrees that

this one- liquor store

is the

scourge of all Eskimos

living in or visiting

Bethel, in the

last election the store

was voted permanence-for

it pays. Some years earlier

it had been voted closed,

with a sigh of relief,

but the

loss of revenue was too

severe. Beyond the liquor

store are three richly

stocked general stores

to tempt the Eskimo further

in his

tastes for conspicuous

consumption, as well

as waste.

Bethel has a

genuine

slum, poor as shoddy

cabins only

can be

when shadowed

by affluence.

So

in one sense

Bethel is

the world that

the White man’s

education is selling

to the Eskimo. And as

a world it has most of

the White man’s

failures. Bethel could

be looked upon as a proving

ground for coping with

White ways and perversities.

Hence it could be

a very educational spot.

The

Alaska State School

in Bethel holds itself

aloof

(as do most

schools) from

the larger

classroom, the

city, even

though

its

superintendent is aware

and resentful of that

fact. Education

in the

Bethel School

cannot be judged by such

extreme standards, but

considering how intimate

Bethel

community problems

are to the

school, education could

do far more than it is

doing

for

improvement

of community

life. It should

be judged on how well

it prepares and encourages

Eskimos to deal

with their

immediate social

and economic circumstances.

This

writing will examine

some

of these educational

goals further

on in

the text.

Eskimos themselves

may be using Bethel at

large

as

a school

far more effectively

than

they

use the state

school.

Bethel

is the

site of

the most militant co-op

and the center for the

most politically

determined

Eskimo group

in the

tundra.

Villagers from

nearby Nunapitchuk form

the backbone of the salmon

cooperative

based in Bethel and are

the leading group in

the Alaskan Native Association.

Nunapitchuk had

a rare and early educational

opportunity. Through

default

there was a four-year

period when the

only

teacher

in the school

was

an Eskimo

woman. This period of

teaching paved the way

for the following

set of

BIA teachers

who also

taught

in terms

of community

education. One of these

teachers

married an Eskimo girl

and at the time

of this

fieldwork had moved to

Bethel where he was one

of the leaders

of the

fishing co-op. The cooperative

was given

national

news coverage

when Walter Hickel, then

governor of Alaska, under

pressure from

canneries in Seattle

tried illegally

to break it.

When we consider

the state school, we

cannot ignore the

very

educating experience

of this Eskimo cooperative.

ANCHORAGE,

ALASKA’S BIG CITY

Anchorage

is a boom town. It romantically

likes to think of its

boom as the derring-do

of a latter day gold

rush. Driving around

Anchorage is

more reminiscent of real

estate developments around

Seattle and the petty

exploitation of millions

of American dollars dumping

inflation

on the Arctic.

For the

Eskimos, Anchorage is just a city, and they

are in

the minority

as

they would

be in

any city

in the “Lower

Forty-Eight.” Five

thousand Indians, Aleuts,

and Eskimos live in

Anchorage. Seven percent

of the

school population is

Native. The superintendent

of elementary

education suggests

that actual school

attendance

represents only a part

of the Native population

of school age. He claims

that many

children are not in

school at all because

Natives

find the schools painful

and unfriendly. This

reflects clearly the

fact that the public

schools are not for

Eskimos or other Natives.

Education

here is the most

conventional White

urban education, just

as Anchorage

city life is White

urban society.

Overtones

from our

film suggest that

we are looking

at Native

education in any

middle-sized

American

city. Actually

in

Anchorage there

is a lower percentage

of non-White students

than

would be found

in many

American city schools

today. There is

a very small Black

population in Anchorage

and an

even smaller

Oriental community,

so that Anchorage

might be expected

to be less sophisticated

about educating

ethnic

minorities than many

other American cities.

Though

Anchorage has the

largest Native community

in Alaska, this fact

appears to have

little or no effect

on

programming in the

schools.

Possibly

this is the educational

tragedy

of Alaska. Statistically

the Eskimos

are a very

small group

of people. They

have as yet little political

power. Only since

the

oil

strike

on the North

Slope have

their interests

been an issue in Alaskan

affairs.

When

viewing the

Anchorage

school film, it

is hard to realize

that this

is Alaska. Even

more than

Bethel, Anchorage

is the American

experience. We

can

look at Natives

in school here as affected

by very much the

same

circumstances

as in Oakland,

Seattle, or Spokane.

The

simple

fact is that Anchorage

really is an American

city. Its

schools present

a fair picture

of Natives

in

school attendance

anywhere

in the country.

|