WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT

WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT

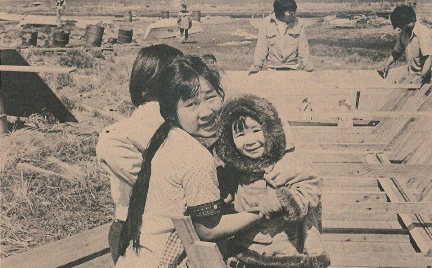

"Everyone at Nightmute and along the coast lives with the sea. This winter especially we are short on food. It is an unusually long winter: There is a shortage of food, and since we survive on seafoods we would like to ask if you would please consider our needs before passing the bill taking away our life survival.If the bill prohibits hunting of sea mammals at any time the people will listen to the hunger of their families and hunt even against the bill. The whole Western Alaska coast-line will be violating the law and the jails will be constantly filled if the law is strongly enforced. The hunters go to the sea to take care of the subsistence needs of their families, and not for sports... We do not want our children to break any laws. We have always tried to follow all the laws of the government... But we will not sit around obeying a law when our families are starving."Isidore Tulik, Nightmute, l9725

Fortunately for Isidore Tulik and every other Native person in the region, when Congress enacted this law it was modified to allow subsistence use of marine mammals. But his feelings are typical of the frustration felt by our people every time a law opposing or limiting subsistence hunting and fishing is proposed, enacted, or enforced.

To the village hunter and fisherman, fish and game regulations have been something handed down from people in Anchorage, Juneau and Washington D.C. who apparently know or care little about the subsistence needs of the village people. After the laws have been passed without the involvement of the village people, the enforcing agencies usually haven't even bothered to discuss the new regulations with the people. This lack of involvement and communication has left people with mixed feelings of fear, guilt and resentfulness. A woman from Emmonak has described the problem like this:

"At this time many of the Eskimo people don't have too much to eat at home.. . One of our biggest problems is understanding the law, the laws that are enforced by the Fish and Game Department. Many of the older people don't read or write. They don't know the regulations and rules and usually are too scared to even help themselves."

"Many of the older people don't read or write. They don't know the regulations and rules and usually are too scared to even help themselves."

When the rules and regulations have not been clearly explained to people, they have been troubled whenever they go out hunting. Mr. Luke Tukaya has put his feelings this way:

"I get a guilty feeling what works inside of me. So I feel limited to what I can get from the land. And every time I go out hunting, survival hunting, I have this guilty feeling that I am stealing behind somebody's back for the food I need for myself and my family in the village."

It has to be emphasized that the bitterness, fear, suspicion and hatred that fish and game regulations have generated among rural people is not because of some basic incompatibility between Native people and regulations. It is because regulations and policies have almost always been enacted arbitrarily and enforced with little or no regard to the needs and feelings of Natives and other rural people.

If regulations are meaningful, if they truly balance protection of the resource with needs of the people, if the rural people understand the regulations, if the regulations are not handed down in a condescending manner—then people in the villages may become the strongest supporters of the regulations and management policies. There is no group which has a greater interest in protecting fish and game resources than village people who depend upon them for subsistence. But unless management agencies make some significant changes in their relationship with the rural subsistence users, these people who should be the most ardent advocates of fish and wildlife management will become ever more bitter and aggressive in their struggle against management agencies and their policies.

"Every time I go out hunting, survival hunting, I have this guilty feeling that I am stealing behind somebody's back for the food I need for myself and my family."

In this chapter we will suggest some specific steps that can be taken on the State, national; international and local levels to develop and implement meaningful fish and game management programs.

State of Alaska Fish and Game Management

In Alaska the primary responsibility for managing fish and game resources falls to the State of Alaska. Whether the birds, animals, or fish are in State, Federal, or private lands, they fall under the jurisdiction of the State Department of Fish and Game. Notable exceptions are the management of migratory waterfowl and most marine mammals which come under the Authority of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Over the years the policies and actions of both agencies have caused the people of the Delta to regard them with distrust, fear and bitterness. The challenge of the coming years will be for the agency people and the Yupik people to work together in finding ways to protect and enhance the fish and wildlife and the subsistence way of life that depends upon them.

The Alaska Department of Fish and Game's management responsibilities are tied directly to the constitutional mandate to manage fish and game on a sustained yield basis. To fulfill this mandate the ADF&G has some authority to establish preferential use rights and to take various actions to enforce the fish and game regulations. As a first step to correct long standing problems with subsistence use of fish and game, ADF&G Commissioner Jim Brooks issued the following Subsistence Policy Statement.

"While fish and game resources were once a crucial factor in the survival of all Alaskans, a growing population segment is becoming partially or totally independent of these resources. This change is the result of advanced food production technologies elsewhere, rapidly improving logistics, and a growing immigrant population whose demands mainly involve recreational and non-consumptive resource uses.

" Nevertheless, direct domestic utilization of fish and game is still vital to the maintenance of most rural Alaskans and is an essential supplement to the larders of some urban citizens. Beyond directly satisfying food requirements, home consumption of fish and game tends to preserve indigenous cultures and traditions and gives justification and gratification to a strong desire possessed by many to hunt and fish. The latter functions seem genuinely important to the physical and psychological well-being of a large number of Alaskans.

" The very rapid changes occurring in Alaska now give rise to grave concern that the accustomed contribution of fish and game to subsistence economies will be threatened: By reason of culture, location, economic situation or choice, large numbers of people will find it impossible to abandon or alter their way of life at a pace paralleling changes brought by new shifts in land status and ownership, non-renewable resource developments, road extensions, transportation improvements, and a phenomenal rate of population growth. In recognition of the above facts and of the responsibilities mandated to the board and the Commissioner, the following statements which express the views of these authorities are considered necessary and timely.

" The existing variety of cultures and life styles in Alaska are of great value and should be preserved. While limitations on the productivity of fish and game must discourage continued increases in the numbers of subsistence type resource users, domestic utilization is still of fundamental importance to many Alaskans, and accordingly it is assigned the highest priority among beneficial uses. Within legal and biological constraints, fish and game will be allocated to subsistence users on the basis of need. It is understood that the needs of individuals, families or groups will differ in type and degree and that subjective judgments will unavoidably be necessary in weighing actual need.

" Elements considered in establishing the level of need include culture, custom, economic status, alternative resources, location, and voluntary choice of life style. It is further understood that subsistence requirements will not make equal demands on all resources in all areas, and that recreation, commercial and, non-consumptive uses will continue to be permitted where and to the extent that they do not truly interfere with or jeopardize subsistence use.

" It is the expressed intent of the Board and the Commissioner to be guided by the above stated policies in fulfilling their duties of managing Alaska's fish and game in the face of drastic changes in land status, nonrenewable resource development, and economic and cultural changes."2

This policy statement is a promising step toward the proper

management of subsistence fish and game resources, but there can be quite

a gap between good intentions and effective action. At the Land Use Planning

Commission's 1974 subsistence conference David Jackman, who was later

named the Commission's State Co-Chairman, cautioned that, "Over the

years the Board of Fish and Game has to some extent made ad hoc provision for protecting subsistence use where necessary

in the way it chose to regulate seasons, bag limits, and the methods and

means of taking. However, the Board has no clear statutory authority to

explicitly recognize priorities among uses in the regulations it adopts.

If the direct regulatory authority of the State over the use of fish and

game resources on all lands is to be used as a means of protecting

subsistence use, such an additional statutory authority would be essential."2 In

other words, ADF&G's proclaimed interest in subsistence resource

management needs to be supported by a formal resolution of the Governor

or the legislature declaring subsistence use of fish and game the priority

use.

This policy statement is a promising step toward the proper

management of subsistence fish and game resources, but there can be quite

a gap between good intentions and effective action. At the Land Use Planning

Commission's 1974 subsistence conference David Jackman, who was later

named the Commission's State Co-Chairman, cautioned that, "Over the

years the Board of Fish and Game has to some extent made ad hoc provision for protecting subsistence use where necessary

in the way it chose to regulate seasons, bag limits, and the methods and

means of taking. However, the Board has no clear statutory authority to

explicitly recognize priorities among uses in the regulations it adopts.

If the direct regulatory authority of the State over the use of fish and

game resources on all lands is to be used as a means of protecting

subsistence use, such an additional statutory authority would be essential."2 In

other words, ADF&G's proclaimed interest in subsistence resource

management needs to be supported by a formal resolution of the Governor

or the legislature declaring subsistence use of fish and game the priority

use.

Subsistence priority use does not need to be defined on racial grounds which raise constitutional as well as ethical conflicts between Native and Non-Native. Rather, priorities should be established along lines of necessity. A meaningful and practical breakdown of priority use based on necessity is as follows:

"Subsistence priority use does not need to be defined on racial grounds which raise constitutional as well as ethical conflicts between Native and non-Native."

To implement successfully such a system of priority use

the Alaska Department of Fish and Game would have to carefully and consistently

monitor the fish and wildlife populations and then relate the availability

of fish and game in a certain region at a certain time to the needs of

the different user groups. In many instances all four user groups would

be able to use the fish and wildlife resources. But if demands on a certain

wildlife population began to be greater than the availability of the resource,

then priority use would be designated for one or more of the user groups.

To implement successfully such a system of priority use

the Alaska Department of Fish and Game would have to carefully and consistently

monitor the fish and wildlife populations and then relate the availability

of fish and game in a certain region at a certain time to the needs of

the different user groups. In many instances all four user groups would

be able to use the fish and wildlife resources. But if demands on a certain

wildlife population began to be greater than the availability of the resource,

then priority use would be designated for one or more of the user groups.

It might be that local and Alaskan residents would have priority use of most species in a region but that in some specific areas some species of great sport value, such as trophy trout or mountain goats, would still be available to sport hunters. If a certain wildlife resource became severely limited, only the local resident subsistence user would be allowed to utilize it. Should that certain resource become truly threatened, then even the local subsistence user would have to be limited in order to protect the productivity of that certain endangered population. Likewise, if a declining wildlife population is revitalized, its use might be expanded from the local subsistence user to all user groups.

In managing fish and game populations on a priority user basis it is important that the different user groups not become polarized. The use of the fish and wildlife resources should not become an issue between Native and non-Native or between local residents and residents of other regions, or between subsistence and sport users.

If properly planned and carried out, a priority use system should provide more fish and game for more people. But, if the user of these resources are not carefully considered and managed with a sense of cooperation between the various user groups and the managing agencies, the conflicts will become intensely bitter and, in the end, destructive to the fish and wildlife resources.

Once the ADF&G's intentions are bolstered by a direct subsistence priority policy, there are two basic administrative approaches that the Department could use in subsistence resource planning. One would be a "limited entry" or permit type system to select subsistence from non-subsistence users. If a true limited entry approach became too much of an administration nightmare, the State might administer a licensing system on a case by case base within areas officially declard as subsistence zones.

The second approach would be to make it difficult for non-subsistence users to obtain game in important subsistence use areas. This method would consist of setting bag limits, defining the means by which game could be taken, establishing times during which it may be taken, and limiting the types of vehicles that could be used. One advantage of this approach is that it could be flexible; regulations could vary from one part of the State to another and could change with fluctuations of fish and game abundance and needs of subsistence users.

In addition to the limited entry and restriction of access approaches that the Department of Fish and Game can use for subsistence planning, there are a number of specific steps it could take to improve its program in rural areas.

By far the most important goal for the State of Alaska to help perpetuate the subsistence resource base is to protect the State's fisheries from deteriorating any further. This will require a number of specific actions:

Federal Wildlife Management:

Marine Mammals and Migratory Waterfowl

Marine Mammals

Although the State Department of Fish and Game has the primary responsibility for fish and game management within Alaska the Federal Government has management~ authority through the Departments of Interior and Commerce for several species which are vital to subsistence living on the Delta. These species are the migratory waterfowl that receive protection under international treaty and marine mammals which are protected by the Marine Mammal Act.

The Marine Mammal Act evolved out of a well intended concern of many Americans to end the commercial exploitation that was rapidly depleting some marine mammal species such as the great whales, polar bears and seals. In the rush to protect these species, legislation was nearly passed with language that would have prevented Native people from utilizing marine mammals like the seals and walrus which are in no danger of extinction and which are essential to the well being and very existence of Yupik and other Native people in Alaska. When the Marine Mammal Act was finally signed into law it prohibited the hunting of marine mammals except by Alaska Natives who need to do so in the course of their subsistence living. Further provisions of the Act allowed limited commercial use of marine mammals and gave the Secretary of the Interior the right to impose limits or a moratorium on Native use of certain marine mammal populations if such action is necessary to preserve the populations.

Can the Marine Mammal Act really protect both the productivity of marine mammal populations and the subsistence needs of the village people?

Two years after the Marine Mammal Act of 1972 was enacted, the U.S. House Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries held hearings to evaluate the effectiveness of this law. Testifying for Yupiktak Bista, Harold Napoleon outlined how the act relates to current subsistence use of marine mammals in this region.

"Because the people directly concerned and involved and affected by the Sea Mammal Act were unable to come themselves and testify, I was sent here to testify in their behalf and give you their thoughts on the sea mammal legislation. Now there is no real problem as far as they are concerned with the Sea Mammal Act itself—there are several points they feel should be changed and I will get to that later in my testimony.

" I think before I go into that I'd like to talk a little bit about the use of the sea mammals by those villages on the coast and also those villages away from the coast. The primary mammal used by the people on our coast is the hair seal. The hair seal is used en toto, in other words, everything is used that is a part of the hair seal. The skin is used, the fat is used, the meat is used, the intestines are used—except for the bones which are inedible—those are not used. The fat is sent up the two rivers to those Eskimos further up the river and also carried to those villages in the interior further away from the coast—and also the villages on the coast. There is not that much walrus being caught on the coast of the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta. There are some taken at Nunivak Island and also on Nelson Island and further down toward the Kuskokwim, but very little walrus is caught on the Yukon Delta. Whenever walrus is caught, it is then used en toto.

" Walrus hides have never been used for dog food—that has always been consumed by the people that caught the walrus themselves. They don't eat the walrus hides the day they get it but they cook it and put it in barrels where it is stored for the rest of the year. The blubber they also use, along with the meat and the intestines and the fat. So you see, the walrus is used en toto.

" The Beluga, which is another mammal, is becoming rare in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta. There was a time when there were a lot of Beluga going through our area, but not at this point. I think there's only one village that I know of this summer that has caught any Beluga—which is the white whale, they were plentiful at one time but now they are scarce; the reasons, I don't know."Now as far as the Sea Mammal Act is concerned, a regular family will average out about six hair seals each year—that's how much a family is going to use in a year—the meat they are going to dry or eat at that time. The fat they are going to store and the skins are going to be dried and used for mukluks, coats and whatever. However, the sea mammal legislation says that the people in the villages cannot sell unfinished skins.

" I think this was in part done to discourage the large taking of hair seal just to sell the skins but I think the opposite is true now. Say there is a village of 50 families and each of these families were to get six seals you'd have about 300 seal pelts in the village. Now in two years that would be 1,200 seal pelts in the village. Now it is true that the use of the pelts is not as widespread as it used to be, the people are not making their umiaks out of seal skins any more. They now have regular skiffs. They are not using seal skins to make their kayaks anymore. They're using canvas instead because it's a lot easier to work with.

" They are not able to manufacture a great number of seal skin products because they can't do that. Also, they can't get rid of these seal skins because they are not allowed to do so by the Act. Previously, in Kodiak, they did sell their raw skins to furriers in Seattle and other points. What they would like to see changed is that the take of the seals remain open as long as the family will use all the parts of that seal. In other words, if a family takes ten seals in one year it will take those seals with the knowledge that it is going to use those ten seals. But at the same time they should be able to make the best use of the pelts they are going to be getting from these seals. If it means making mukluks that's what they are going to do. But if it means selling them to furriers, that should also be open. Because if the people don't use these pelts they are going to waste in the village.

" This is their main point of objection. They are not saying the seals should be killed for the pelt, they are saying they should be allowed to take any number of seals they need and then make the best use of the pelts that they can.

" Also, as far as the State getting jurisdiction of the sea mammals, I don't know what the consensus is about the State taking over the control of the sea mammals, but for the most part I think that such a move would be beneficial not only to the people in the villages but also for the whole management of these species."6

In discussion after his testimony, Napoleon was questioned about wastefulness. Congressman John D. Dingell of Michigan said:

"Well the statute specifically says, Mr. Napoleon,... in each case is not accomplished in a wasteful manner. We expect that the Natives under that exemption will first of all, utilize for subsistence or for the very narrow craft purposes any animals under the exemption. We expect them not to be wasteful. We operate under the assumption that when they are going to go in business that they will then be bound by the same rules everybody else is bound by. I don't consider that to be unfair."6

To this Napoleon replied:

"As far as we know there has been no waste of the animals in the area that we come from. Maybe in the years when there was a bounty placed on the hair seal there might have been some waste because at this point they were actually encouraging people to go and kill a seal and they would pay $3 for fins. They automatically reversed from that stand to another stand which said you just couldn't do it unless you (avoided waste)—which is a reasonable change."

" ...Our people advocate the continued use of the seal for subsistence purposes. That is what they are mainly interested in. This is something I want to make clear that the majority of the people out there like sea mammal legislation because it does prohibit the wasteful use of seal. They don't like the selling of the seal skin—just to sell it to somebody else. They want to continue use of the sea mammal, and there is no waste on their part."6

Congressman John D. Dingell also asked what Yupiktak Bista thought of restrictions being placed upon Native taking of marine mammals that are endangered. To this Napoleon replied:

"...Such a policy would be good if that species was in fact endangered. But then again keeping open the possibility—well I think its always open—the possibility that a hungry man will kill whatever he can get his hands on. As far as the sea otter and the polar bear are concerned, I think if they are endangered, they should be protected."6

In summary, in this region at least, the Marine Mammal Act of 1972 provides a basic management approach which accomplishes two important things.

The problems the Federal government and Native people have with the management of migratory waterfowl could be greatly reduced if policies similar to the Marine Mammal Act of 1972 were enacted to both protect the waterfowl and provide for the traditional, legitimate and non-wasteful use of these birds by village people.

Migratory Waterfowl

"As far as I can remember, my forefathers have lived off the land and they must live off the land now. In the springtime of the year we take goose eggs and duck eggs and geese. And all the year we do the same thing because we don't have money to buy white people's grub. We have to live off the land."Joseph Albritez

Waterfowl have been important to Eskimo and Indian people for a long time.

"We can only surmise man's first

encounter with the snow goose," writes Paul Johnsgard in Song of the North Wind... . It might have occurred as recently

as 10,000 years, or perhaps as early as 25,000 B.C. For a period of about

10,000 years, or until about 13,000 years ago, a broad causeway was open

to land travel between Asia and Northwestern North America in the form

of the Bering land bridge. . . Along this causeway came a variety of land mammals, including the first

humans ever to set foot on the North American continent... Both groups

of immigrants (Indians and Eskimos) would live in peace and harmony with

the snow goose."

"We can only surmise man's first

encounter with the snow goose," writes Paul Johnsgard in Song of the North Wind... . It might have occurred as recently

as 10,000 years, or perhaps as early as 25,000 B.C. For a period of about

10,000 years, or until about 13,000 years ago, a broad causeway was open

to land travel between Asia and Northwestern North America in the form

of the Bering land bridge. . . Along this causeway came a variety of land mammals, including the first

humans ever to set foot on the North American continent... Both groups

of immigrants (Indians and Eskimos) would live in peace and harmony with

the snow goose."

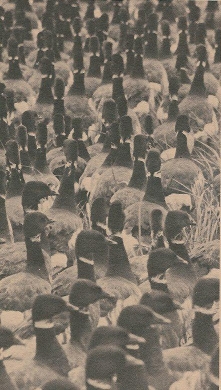

The snow goose, canadian, emperor, white-fronted and brant geese, the ducks and swans, cranes and sea birds—all have been used for subsistence since the North American continent was first settled.

Over the thousands of years that people have lived on the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta the relationship between the people and birds has been part of the balance of nature. The birds were hunted, used for clothing, depended upon for food. Each spring the people looked forward to the return of the ducks, geese and swans, and each year these birds returned in great numbers.

This relationship is much older than Western civilization. But does it have a place in the modern world?

A lot of people in this region think it should. As Ray Jenkins has said, "At Chafogtalik its hard to live in the winter. We catch only needle fish, besides that we have flour and tea. That's all we have to eat in the winter. When spring comes we are glad to see the birds come to their places, because we got something more to eat besides needlefish, flour and sugar."

Today this traditional use of waterfowl in our region, and by Native people elsewhere in Alaska, is threatened by two factors:

These problems have created an extremely emotional and desperate controversy which raises a number of questions.

Do Native people still need waterfowl?Can existing rules and regulations permit subsistence use of waterfowl?Is subsistence use of waterfowl compatible with sound waterfowl management?How can conflicts between subsistence and sports use of waterfowl be resolved?

The problem of management and subsistence use of waterfowl is not a local problem. It is a problem that spreads over every river, lake, marsh, plain, grain field, and sea coast that the birds which nest on the Delta visit during their migrations. As the world has become heavily populated and industrialized the waterfowl populations have felt the pressure in their nesting, migrating and wintering areas. And the birds that nest on the Delta are particularly wide ranging, as a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service study summanzes:

"A total of 170 species of birds have been observed on the Yukon Delta. Of these, 136 probably nest there, and many are common migrants. A few visitors from Asia have been recorded infrequently. Only 13 species are year-round residents. During migration, some birds from the Yukon Delta probably reach most provinces of Canada, every state in the United States, every state of Mexico, all countries in Central and South America, Antarctica, virtually all of the Pacific Islands, all Asian countries bordering the Pacific, Australia and New Zealand."

Roughly speaking, that is the extent of the problem. In these different parts of the world the problems of subsistence use of migratory waterfowl on the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta surfaces in two forms: The ever-increasing hunting pressures pollution and loss of habitat on one hand; and the formulation and enforcement of treaties and regulations, which often disregard Indian and Eskimo subsistence needs, on the other.

A fairly objective summary of Native subsistence use of migratory waterfowl, management objectives and the string of legislation and treaties that relate to subsistence use of waterfowl has been made by Albert Day in a report to the Director of the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife. Titled Northern Natives, Migratory Birds and international Treaties, the report was prepared in 1969, but has been classified confidential and never made available to the public. Day's report begins:

"Since the beginning of time, the Eskimos and Indians of the Far North have looked with longing anticipation to the return of spring, when great flocks of geese, ducks, and shorebirds return from their ancestral southern wintering grounds, build their nests on the tundra, and provide eggs and fresh meat for Natives. Winter diets of seal, whale, dried salmon and shee fish, with occasional caribou and moose meat for the lucky ones, are forgotten as fresh flesh and blood arrive once again. Although white-man's foods have replaced some of the ancient primitive diet, the return of migrant waterfowl is a gala occasion as long Arctic winters lose their grip on the Northland.

" Historically, the Alaska Native has been totally dependent upon the resources of the land for his livelihood and existence. Meat of various mammalian species taken on land or sea, or of birds, migratory and resident, or of fish, remains to this day the basic diet. Prior to the arrival of the white man, meat was consumed to the exclusion of all other food items except occasional native plants. The Eskimo food quest was thus centered wholly in the wildlife of the region. It is this, in its various manifestations, which underlies his adjustments in ecology and culture.

"Spring celebrations attracted several groups or villages together for 'drives' on molting waterfowl where hundreds and even thousands of birds could be obtained easily."

"Because food gathering is the foremost motivation, and mammals, birds and fish form the basic source of livelihood, the hunter is the leader of the community. A man's standing within his group or community is directly related to his success as a good food gatherer.

" In bird hunting, the Alaska Native tends to be selective. Fowl that form an important part of the Native diet are principally ducks and geese, and their capture becomes the chief preoccupation for that part of the year when they are abundant and available—principally during the spring nesting season and the later flightless molts.

" Prior to the introduction of firearms, waterfowl were harvested by primitive, ingenious means. Baleen nets were stretched in narrow passes or at headlands where birds flew low during migration. Bolas were thrown, nets were placed in lakes to enmesh diving ducks; spears and clubs were used on flightless, molting waterfowl; and snares were used for ptarmigan, owls and gulls.

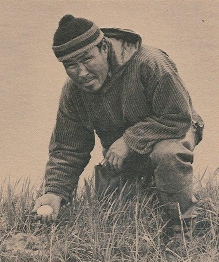

" Women and children participated in harvesting this wealth from the tundra by gathering eggs. In some areas, sled dogs were turned loose to fend for themselves during the summer, subsisting mainly on flightless birds and eggs. Village location, in some cases, was dictated by the closeness to nesting concentrations or to lakes where large numbers of ducks or geese molted. Spring celebrations attracted several groups or villages together for drives on molting waterfowl where hundreds and even thousands of birds could be obtained easily. Colonial nesting sea birds were hunted for meat, eggs and skins."Traditionally, Eskimos move their villages to 'spring-camp' by dog team in early spring—locations where migratory waterfowl are easily taken and fishing through the ice and after breakup is good. The first ducks are eaten with gusto— usually raw—for, in some areas, this is the first fresh meat consumed since the previous fall. Fish, dried or fresh, has been the mainstay dish during the long winter months.

"Besides providing meat for food and skins for clothing, Waterfowl have always been deeply involved in Native folklore and mythology. Bird beaks, bones and feathers adorn ceremonial dress and masks, and the lore of birds is prominent in stories of Eskimo ancestors. The computation of time is on a lunar basis consisting of 13 months. The Eskimo word for May is 'Tonmeretutkeraat' meaning 'Geese Come' for August 'Ecerreat' meaning 'Ducks Lack Feathers.'

" King remarks that the prohibition against the Natives taking waterfowl in spring and summer months is to an Eskimo youngster more tragic than telling white kids in the States that they must stop hunting colored eggs at Eastertime, or forego Christmas trees during Yule celebrations.

" Hunting methods have changed with the passage of time and the introduction of white man's culture. Bolas, spears and baleen webs have been replaced by high-powered shotguns and nylon nets. In most areas, dog teams have given way to mechanical marsh buggies, snow machines, fast-shallow draft boats with high-powered outboards, and even airplanes on skis and floats. Yet, these modern devices require hard cash—a commodity in very short supply among Native hunters — so traditional practices persist over most areas of the Eskimo country. The Native dependence on fish and game remains the same in the smaller, remote villages.

" During recent years, important changes have gradually occurred. Official Federal and State agencies have increased their observations of the extent and importance of Alaskan waterfowl breeding grounds. Aerial transect surveys of the principal concentrations were initiated in 1957, ten years later than those established for the Prairie Provinces of Canada, for for the Dakotas, Minnesota and other important more southernly nesting grounds. These observations revealed the great importance of Alaska as a nursery ground for many species important to other State and Canadian sportsmen.

" Management of the total continental population, and some species in particular has become increasingly significant as drainage of pot holes and marshes in Canada and the northern States has proceeded unabated, as hunting demands have intensified and as periodic drouths have exerted greater pressure on the nesting marshes that have so far escaped the plow, the ditcher, the new highways, and other inroads of an expanding economy.

"The prohibition against the Natives taking waterfowl in spring and summer months is to an Eskimo youngster more tragic than telling white kids they must forego Christmas trees."

"Furthermore, the legitimate demands of the Eskimos are changing. Around some towns and villages having a good economic base, such as Barrow, Fairbanks, Anchorage and to a lesser degree, Bethel, there is much less need for Natives to hunt for food than in the hinterlands.

" Central to the current problem is the Migratory Birds Treaty, negotiated with Great Britain, pertaining to Canada, in December 1916. A similar treaty between the United States and the United Mexican States was negotiated in March 1937. Thus, Federal responsibilities have long given protection and management to migratory birds over the entire North American Continent, from the Caribbean Sea to the Arctic Ocean.

" Both treaties provide for closed seasons and prohibit sale and traffic in wild birds. Of particular importance to the Alaska problem, they

None of these restrictions recognize the actual needs of the Alaska Natives in 1916, nor do they now.

"The legislative history of waterfowl management in Alaska is discussed in detail elsewhere in this report, but a brief resume here will demonstrate the legal inconsistencies and contradictions which are, in large part, responsible for the present conflict."Chronologically:

"If you don't think it's hard to live off the land, why don't you guys leave your money behind and go out there?"

The convention was not changed. The regulations persuant to the Treaty have not been modified to permit subsistence use of waterfowl. However, the need to make provisions for legitimate subsistence use of migratory waterfowl has been clearly stated many times by village people.

When the Bureau of Land Management held hearings in Bethel in 1956 on the Kuskokwim Withdrawal Area (which became the Clarence Rhodes National Wildlife Refuge) the following statements were among those made by village people. Their intent remains as true today as it was then.

JOE FRIDAY: (Mr. Romer's interpretation)—"Out at Chevak where he came from, they don't have any money or any way of earning money. They have to live off the land, so it doesn't matter whether the season is closed or open, they still have to live off the land. If you don't think it's hard to live off the land, why don't you guys leave your money behind and go out there and see if you can live off the land?"3

JOSHUA PHILLIP: (Mr. Romer's interpretation)—"He says in the spring of the year when they go out to their hunting ground they are short of food and when the geese come they have to kill the geese in order to live until they start catching muskrats and other animals they can eat.., they just kill enough geese for their own use in the spring of the year."3

MAXIE ALSTIK: (Mr. Romer's interpretation)—"When the Natives go hunting in the fall they live off the land. In the spring of the year when they run short of grub or food, they go out there and kill anything so their kids won't go hungry, He says if you people came here to make a refuge or try to take the land away from these people—it's like taking food away from their children. It is like taking food away from somebody that is going to eat."3

MR. MICHAEL: "I have a personal distrust of the Fish and Wildlife Service. I don't want any promises made to me or to my people unless I can see them in the game book. We have a game book, but I distrust the Fish and Wildlife agents on the reason that we are promised right tonight at this meeting that come what may, next year whoever take eggs, you go to jail, and I have to survive on that. My kids and I have to survive on that. I'm speaking for myself and countless other men, all people. We don't want to break the law. We don't want to make so many laws here that we can break them so easily that we can get in jail. No, we don't want that, but the people here during the springtime have a very tough type of life."3

The strong feelings of village people and the reasons for providing for their subsistence needs in regulations were reinforced by a Report to the Secretary of the Interior by the Task Force on Alaska Native Affairs in December 1962. The Task Force made the following comments and recommendations about migratory waterfowl.

"We don't want to make so many laws here that we can break them so easily that we can get in jail"

"Judging from the comments made by some non-Natives, there is a feeling that because Eskimos and Indians now hunt birds with shotguns rather than with nets and snares, because their fish hooks are of steel rather than bone and wood, and because they hunt whales with explosive devices instead of harpoons with bone heads, that hunting and fishing are noncommercial pursuits or sport rather than subsistence activities upon which the Natives depend in order to secure raw materials for their food and clothing. Although modern technology has indeed improved the efficiency of the Native fisherman and hunter, this technology has not necessarily made him less dependent on wild game and fish.

" In all of the Eskimo and Athabascan villages visited by members of the Task Force, comment was made to the effect that the season on migratory birds should be open during the spring.

"Many Eskimos stated that simply winking at law violations is not the way to solve the problem, for this, in essence, makes the Natives and the Fish and Wildlife Service parties to violation of an international agreement."

"Early in 1961, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service turned its attention to stricter enforcement of the Treaty, arresting some Natives for illegal possession of ducks and geese. The result was near panic in several villages. In May of 1961, Governor Egan directed a letter to the Secretary of the Interior, pointing out that the relatively few Alaskan Indians, Eskimos and Aleuts were not a threat to the preservation of migratory birds. He emphasized that the slaughter of birds by sportsmen far south of Alaska breeding grounds had resulted in the original treaty, the enforcement of which would threaten the very existence of Natives in some of the villages...

" After receiving this letter (Governor Egan's) and studying the matter further, the Department of the Interior abandoned its program of aggressive enforcement against Native subsistence hunters."

" However.., many Eskimos stated that simply winking at law violations is not the way to solve the problem, for this, in essence, makes the Natives and the Fish and Wildlife Service parties to violation of an international agreement."

"Although modern technology

has indeed improved the efficiency of the Native fisherman and hunter,

this technology has not necessarily made him less dependent on wild

game and fish."

"Task Force Recommendations

" No. 2 The urgent need for a reexamination of the terms of the 1916 Migratory Bird Treaty to determine whether relief for the Alaska Natives can be obtained administratively, or whether the Department of the Interior should seek to have the treaty amended."

No modifications to provide for subsistence use of migratory waterfowl were made in the regulations or the Treaty as a result of this Task Force study in 1961. Nor did any of the needed modifications come from the 1969 Day Report.

It is now 1975. It is still illegal for Yupik people to use migratory waterfowl as their ancestors did. The law still forces village people to either stop using these birds as their forefathers did or to break the law. In this way the Treaty and its regulations continue to promote cultural extermination.

The law may not be rigorously enforced in the rural areas, but as one Fish and Wildlife Service official has put it, "The day will come when we will have to enforce these regulations." Should an attempt be made at this time to amend the Treaty? Albert Day concluded his report with a discussion of this question which remains relevant today.

The Answer— The Evidence

It seems abundantly clear that the Migratory Bird Treaty negotiated with Great Britain and signed in 1916—more than fifty years ago—was lacking then as it is now in its provisions for meeting the needs of the aboriginal peoples of the Far North.

Search of the literature reveals that practically no thought was given to the Native Indians and Eskimos who for untold generations have relied heavily on fish and wildlife for their food, clothing, heat, and other requirements of human life in an exceedingly hostile environment.

The only logical conclusion is that little was known in those days of the distribution of nesting waterfowl nor the dependence of the Natives on them for food and clothing.

Neither Canada nor the United States in Alaska has ever enforced the strict provisions of the Treaty in areas where the Native Indians and Eskimos actually need waterfowl for food. Such arrests that have been made were either for waste or around centers of population where there is no longer a need due to changes in living conditions such as Bethel and Barrow in Alaska and a few similar places in Canada. The administrative agencies have always been most tolerant and sensible in enforcement policies where need exists. The evidence demonstrates quite clearly that there is still a real need for a continuancy of this liberal policy where need exists...

The numerous citations and comments compiled earlier in this report gives substantial evidence that the Eskimo spring and summer harvest of migratory birds in Western Alaska has had little effect on the continental supply of birds of interest to sportsmen elsewhere in the United States and Canada.

Later, on August 28, 1925, the Secretary of Interior issued Regulation 8 which states: "An Indian, Eskimo, or half-breed who has not severed his tribal relations by adopting a civilized mode of living or by exercising the right of franchise, and an explorer, prospector or traveler may take animals or birds in any part of the Territory at any time for food when in absolute need of food and other food is not available, but he shall not ship or sell any animal or part thereof so taken." This regulation stood without challenge from 1925 until it was repealed by the Alaska Statehood Act of 1958, when it was supplanted by a new regulation, almost identical, in the State of Alaska Statutes.

"The Migratory Treaty was enacted to protect birds... but that does not imply the starvation of human beings in the process."

The Office of the Assistant Solicitor feels that the principles enunciated in Regulation 8 are basic. They express the Law of Nature or the Law of Survival and that, no court would hold to the contrary, regardless of the restrictive provisions dealing with the length and dates of the closed seasons.

They comment, "The Migratory Treaty was enacted to protect birds—but that does not imply the starvation of human beings in the process."

They also point out that Section 3 of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 grants wide authority to regulate.

There is the same basic authority now that was there in 1925 to legally recognize the legitimate needs of the Eskimos and Indians of the Far North.

Amend the Treaty?

Amending the Migratory Bird Treaty poses some real problems. Canadian officials point out that the actual process of such a procedure has not even been explored. The 1916 Treaty was made between the United States and Great Britain, and Canada was not granted treaty-making powers until 1932.

Also in Canada the separatist movement in Quebec might cause serious difficulties and lead to the possibility of Quebec demanding a separate treaty between that Province and the United States. Also, the Indian situation in Canada is in ferment as it is elsewhere, and tampering with the Treaty might well be risky. Dr. Munro sums the matter up succinctly when he comments that the idea is, "not appealing."

Also on the U.S. side, there are other serious complications. Should the strict prohibitions against open seasons be changed in the 1916 Treaty, the Mexican Treaty of 1937, containing similar restrictions would still be in force. Any attempt to alter this Treaty would be fraught with danger.

"The Convention Between the United States of America and Other American Republics," signed in 1940 for this government by President Franklin D. Roosevelt does not appear to apply, but should be examined by legal experts if consideration is given to amending the Migratory Bird Treaty with Great Britain. It involves the countries of Bolivia, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Peru, and Venezuela.

Amend the Regulations?

The logical course to resolve the present dilemma would appear to be a simple amendment to the Federal Regulations, based on the authority contained in Section 3 of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918.

This might take the form of:

Such a regulation would restore the same authority that was in effect between 1925 and 1958, it would recognize the situation as it exists today and would legally grant a return to sensible recognition of the legitimate needs of the Alaska Eskimos.

Should the Treaty and regulations be amended? Or should the status quo continue with everyone more or less turning their back on the traditional subsistence uses of waterfowl? This may appear to be practical, but is it right that people should have to worry about when a new directive from Washington D.C. might bring a renewed crackdown on subsistence waterfowl hunting on the Delta? Should people have to live in fear of being arrested, losing their guns, being fined, or sent to jail if they continue traditional spring hunting of migratory waterfowl? In the past, many people have been forced to become stealthy and evasive in order to continue this subsistence activity. People have lost respect for wildlife management regulations and the Fish and Wildlife Service.

Yupiktak Bista proposes that migratory waterfowl be managed in a way that can be respected by everyone.

A well planned effort to either modify the regulations or amend the Treaty should be developed to accomplish these things.

If regulations would assure village people the right to subsistence hunt waterfowl with the possibility of limits if the bird populations begin to decline, people would be able to understand and respect the waterfowl laws. It is likely that many village people would want to become more involved in the wise management of migratory waterfowl.

What if there is no way to amend the Treaty or modify the regulations?

Even though there is an overwhelming argument for changing the legal status of subsistence hunting of migratory waterfowl which many Fish and Wildlife Service officials support, it simply may not be possible to amend the Treaty in the foreseeable future. The primary reason is the difficulty in obtaining ratification of a new treaty by all parties which would include Mexico and all the Canadian provinces. When the Department of Interior recently asked the State Department to assist in arranging changes to the Treaty regulations, the Canadian government refused to agree to changes that appeared to be in conflict with the Treaty. As for amending the Treaty itself, it became apparent that some Candian provinces which view migratory waterfowl as predators to grain crops would probably not agree to ratify a new treaty which provided adequate protection for the migrating waterfowl.

If the Treaty and regulations can not be modified, then other ways must be found to manage migratory waterfowl on sound conservation principles while not foreclosing on legitimate, traditional uses of migratory waterfowl.

Some have suggested that there are aboriginal hunting and fishing rights that come from times long before the Treaty. Others argue that any such rights that may have existed were apparently extinguished by the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act.

"Isn't there a basic right to subsist, to live as one has to, which goes beyond the intent and authority of all the layers of treaties, laws and regulations?"

But, isn't there a basic right to subsist, to live as one has to, which goes beyond the intent and authority of all the layers of treaties, laws and regulations that have been piled upon the Native people who simply want to continue hunting waterfowl as their ancestors did?

"The lawyers are at it again."

In speaking of legal mechanisms that might be attached to a subsistence open to entry program, Anchorage lawyer, Robert Goldberg raised some considerations to the Federal-State Land Use Planning Commission which are pertinent to the discussion of waterfowl management. He said in part:

"We have taken what has basically been an activity which has survived for thousands of years and burdened it with all the best devices that the Anglo-American system of jurisprudence and common law can impose, and that is to say, the lawyers are at it again.

"If you look at this kind of framework of regulation involving an activity so clearly vital to such a large group of people, you see that we are placing a real layer of legal activity, definitional activity, and administrative activity on top of a human activity. Subsistence hunting and fishing, which is a rather simple activity perhaps simply cannot support this legal definition and administrative burden.

" I can foresee, if we elect some sort of process of this type of definition, of this type of management scheme, great investments made by all parties concerned. In technical expertise, in legal expertise, I can see arguments before commissions, I can see very high costs in monitoring, and I can see somewhere along the way losing a sense of what this is all about and what we were trying to do as we approached this whole question of subsistence use.

" ... I think it is important to recognize that a case can be made, notwithstanding the language of the Native Claims Act, that a strong case, I believe, can be made to constitutionally support subsistence hunting.

" At the very least, it seems to me, if this is the only alternative that is open to a person to meet his daily needs of protein, to support him physically, then there can be no question that he is entitled constitutionally...

" ...If subsistence means more than merely everyday providing all the basic protein of food sources for people, it may also still be protected. Subsistence is a means of cultural expression, as we have heard it described and we all recognize. This is also still constitutionally protected."

Assuming that subsistence hunting of migratory waterfowl will remain wrapped in legal controversy for some time, there are nevertheless a number of management actions which might be taken to help relieve the problem.

"There are many people in the villages who are capable and well-qualified in ways other than college degrees to handle wildlife refuge responsibilities."

International Management of Subsistence Resources

International Management of Subsistence Resources

Unlike the more civilized people of the earth, fish, birds and animals don't check the lines and boundaries of maps to know where they are and where they are going. They generally wander about as they please, and as they must to survive. Their wanderings usually follow patterns of seasonal migration that have evolved over thousands of years. And these migrations take many kinds of birds, animals and fish to different continents and oceans, through the territory of many countries and out over the no-man's-land of the open sea.

Each year seals and walrus follow the breaking up of forming of the ice pack as they travel north and south with ocean currents that pass through U.S. territory, Russian territory and the international territory of the high seas. Many fish, such as salmon, herring, and whitefish live both in the open ocean and in the rivers streams and lakes of Alaska where they spawn. Waterfowl that nest on the Delta are particularly wide-ranged. As these birds, animals and fish pass through the territory of different countries they become subject to both the management regulations and the exploitation of the areas they pass through.

Some species, such as the migratory waterfowl and seals, are carefully protected from over exploitation by international treaty. But the great marine mammals—the walrus and whales—and the ocean traveling fish are often subject to the most ruthless kind of exploitation: first come, first served, take as much as you can. As worldwide demands for more food from the sea become more extreme, the exploitation of the seas will become more acute. Along with the need for more food from the sea will come more industrialization which produces more waste materials which eventually end up in the sea, often polluting the ocean waters with materials very destructive to life. Oceanographer Jacques Costeau estimated in 1972 that commercial exploitation and pollution of the seas had already destroyed over 50 per cent of the life in the oceans. This loss of the life and productivity of the sea is almost certain to increase in the future.

If the living things of the sea continue to disappear, our people will also disappear. The Yupik culture is tied to the sea. Like our ancestors, we depend upon the sea for seals., walrus, and whales, for salmon, herring and whitefish. Thousands of years before Christ was born we were living with the sea, getting our oil from seals, drying salmon in summer to have food in winter. People say that we lived in harmony with nature, in balance with what the earth could provide, but we did not think of it that way because this was just the natural way to live. We could not conceive of destroying the life of the sea and land. But now Western civilization, which apparently can not live without laying waste to the natural world, has become dominant. Everyday we hear and see and feel the Western world grinding away at the earth's web of life, steadily killing off the life of the rivers, tundra, forests, rivers, lakes and sea. We are particularly vulnerable to the exploitation and pollution of the sea. As a part of the life of the sea dies, a part of ourselves dies.

"If the living things of the sea continue to disappear, our people will also disappear."

We do not want to believe what history shows us. The large numbers of spawning salmon that once went up the Rhine are gone forever from this great river that flows now like an open sewage canal through Europe. Japan, an island in the sea that has always been closely tied to the sea, now has some coastal waters that are so polluted that eating fish and other foods from these waters can cause people to be stricken with fatal diseases and babies to be born deformed. The great whales are nearly gone, hunted to extinction. The Atlantic salmon is gone. And just to the south of us the great Bristol Bay salmon fishery has collapsed because of over fishing. All experience shows us that Western civilization will eventually destroy the life of the sea and rivers in our region. But we cannot accept this as inevitable, even though there is no rational reason to believe otherwise.

"Thousands of years before Christ was born we were living with the sea, getting our oil from seals, drying salmon in summer to have food in winter."

Is there any way at all to alter this course of events? We don't care to change the world, we just want to bend the course of history a little bit; just enough to allow life to continue in our region. To do this we will have to communicate and seek agreements with other countries of the world. But if we are frustrated in communicating the needs and problems of our region to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, how can we hope to communicate and bring about change on the international level? If it is all but impossible to get some empathy and meaningful responses to our problems from Juneau and Anchorage, how can we hope to find the response in Seoul; Tokyo, and Moscow that is needed to stop the destruction of the seas?

Perhaps there is no way to halt the world wide destruction of fish and wildlife.

If there is a way, it will be found in increased research and careful management. In addition to waterfowl management efforts already discussed, the following considerations should be made regarding marine mammals fisheries and pollution.

Marine Mammals

The Marine Mammal Act protects the animals of the sea from exploitation by U.S. commercial interests, but carries no restriction on the activities of foreign interests. Fur seals are covered by international treaty. Otherwise, there is no international protection of marine mammals.

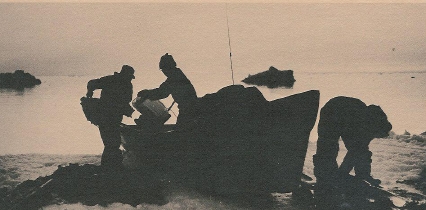

In the spring, walrus travel north with the currents of the Bering Sea. As the ice pack breaks up, men in some of the coastal villages take to the opening sea in skiffs to hunt walrus for the meat, skin and ivory. This hunting is strictly subsistence. Except for some ivory carvings, which may be sold in keeping with the Marine Mammal Act, a captured walrus is usually used entirely within the village. At one time, the walrus population declined severely as a result of overhunting by commercial interests coming from outside Alaska. Today, the walrus population has nearly reached its former size. However, since there is no international law or treaty limiting the harvesting of walrus by other countries, walrus could once again become endangered if seafaring countries like Japan and Russia began taking more of these animals. An international treaty should be formulated and adopted to protect walrus populations from a resurgence of commercial harvesting.

Whales have also always been of great importance to Eskimo people. In the north, the great bowhead whales are hunted each spring by Inupiat Eskimos. In our region, it is the smaller beluga whales that are of greater importance to the subsistence way of life. Presently there is no effective international protection for any whales, and some countries, Japan in particular, have extremely modern and effective commercial whaling operations which have brought some species of whales to the verge of extinction. This exploitation must be stopped. And it can be stopped only by adopting and enforcing a strong international treaty. Even though the United Nations World Environmental Conference adopted a resolution calling for a moratorium on commercial whaling, the International Whaling Commission has refused to adopt a moratorium or any effective research and management policy for whales. This is due not only to the resistance of countries like Japan to limit commercial whaling but also to the reluctance of countries like the United States to forcibly negotiate the issue. Nevertheless, an international treaty must be adopted and it must be adopted before the world's whale populations have declined beyond the point of no return.

"We don't care to change the world, we just want to bend the course of history... enough to allow life to continue in our region."

To develop international treaties that would protect walrus and whales will take some time and effort. The following are some practical steps that could lead to such treaties:

Pollution

Although pollution sometimes strikes in dramatic and obviously destructive blows, such as the wrecking of an oil tanker, it is the chronic, gradual, day by day, year by year, build up of wastes in the world's oceans that is the most lethal. On the State level, Alaska must be extremely careful and often restrictive to prevent offshore oil drilling and the transport of oil over the seas from polluting the ocean. This responsibility is naturally shared by the Federal government which should become more effective in curtailing marine pollution. On the international level, there are several steps that Alaska can take to ward off pollution in the North Pacific and Arctic Oceans.

Fisheries

Overfishing is the greatest danger facing the productivity of Alaskan waters today. And the potential loss of subsistence fisheries is probably the greatest threat to the subsistence way of life today. The experience of Bristol Bay should be a well-heeded warning. In 1974 the once great Bristol Bay fishery was at first closed to commercial fishing and strict limits were even set on subsistence fishing. Although a short commercial season was finally opened in Bristol Bay in 1974, this fishery has been reduced by over exploitation to a fraction of its original proportions. There is much that the State of Alaska must do in the way of limited entry laws and fishery research and rehabilitation. There is also much the State and Federal governments must do to limit the commercial fishing of foreign fleets that pose an extremely serious threat to the North Pacific fisheries.

"Native regional corporations and fishing enterprises should consider refusing to do business of any sort with Japan until that country adopts responsible fishery policies."

Local Management of Subsistence Resources

Local Management of Subsistence Resources

The people in the villages who depend upon fish and wildlife for subsistence have the most direct and perhaps most important role in managing these resources on a sustained yield basis. Traditionally, there was no need for special fish and game management efforts, but with the introduction of the Western way of life has come the need for local people to carefully protect the fish, birds and animals and their habitat. As new things such as roads, dams, industrial development, come to our area village people must learn to anticipate the effects these things may have upon the subsistence resource base. Knowledge of the effects of new developments must then be coupled with our traditional sense of avoiding waste, overharvesting, and disruption of the habitat. To protect our land from problems brought by Western civilization, village people must be aware of modern conservation practices and know how to use the various tools of environmental protection.

To cope with the problems of managing subsistence resources in the modern world we have begun a number of efforts which should be expanded and intensified in the future. Among the steps that have already been taken and those that should be taken on the local level are the following?

Summary of Subsistence Priorities in Fish and Wildlife Management

As we have seen, the fish and wildlife problems that affect the subsistence way of life are numerous, complicated and inter-related. There is no single solution to the present problems. And there is no simple way to avoid problems that will arise in the future. Just as the problems come from many directions, so must the solutions come from many quarters. The key to perpetuating the subsistence resource base in our region and elsewhere lies in communication and cooperation from the local village level through the regional, State, national and international levels.

Return to Does One Way of Life Have to Die So Another Can Live?