HISTORY

OF NATIVE

EDUCATION

IN

ALASKA

Schooling for indigenous peoples has historically tended to be imposed imperialism designed either to assimilate indigenous people into an alien dominant culture and/or to keep them in a second-class status (Reyhner, 2000) .Throughout America, Indian education often meant teaching "Indians to dress, speak and act like white people "as well as to read, write, and do arithmetic. The early paradigm of formal education assumed that education was an effective means of assimilating Native Americans into white society. (Berry, 1968, in Deyhle & Swisher, 1997. ) Szasz 's Education and the American Indian:The Road to Self-Determination, 1928-1973, provides an excellent history up to the time of the 1969 Kennedy Report (Indian Education:A National Tragedy -- A National Challenge ) by the U. S. Senate Special Subcommittee on Indian Education. Since that report, the failed policies of the federal government toward Native Americans are generally blamed for many of the problems experienced by Native Americans in school.

Jon Reyhner, a professor of American Indian/Alaska Native studies and tireless researcher, writes:

Schooling as a formal institution for Indians started with missionaries, and teachers in missionary schools were at least as interested in salvation as in education (Reyhner, 1989) .Alaska Natives 'experiences are similar to those of other Native Americans. The most comprehensive history of Alaska education was written by Frank Darnell in Alaska 's Dual Federal-State School System:A History and Descriptive Analysis. His work is summarized by the Education Task Force in the 1994 final report of the Alaska Natives Commission (ANC) , 2 and provides the basis for this overview.

Russian Schools

The first documented Native school in Alaska was opened by a Russian fur trader on Kodiak Island in 1784 to teach young Alaska Natives "the precepts of Christianity, " arithmetic, and the Russian language. The Russian Orthodox Church started its mission schools about 1796. The Russian American Company also provided training to "Christianize "Native children, "civilize or Westernize them;and to make them more useful servants of the Russian American Company " ((ANC, 1994) .After Alaska was transferred from Russian to American jurisdiction, the U. S. government ordered the Alaska Commercial Company to operate schools on St. George and St. Paul Islands, beginning about 1869. The first American missionary school began in Wrangell in 1877. By the time the last of the Russian schools closed in 1916, American Protestant and Roman Catholic mission schools were operating.

Schools in the District and Territory of Alaska

The Alaska Organic Act establishing the "District of Alaska "directed the Department of Interior 's Bureau of Education to provide education for school-age children "without reference to race. "Most of the children in Alaska at that time were Alaska Native. Presbyterian missionary Sheldon Jackson was appointed the General Superintendent for Education in Alaska in 1885. By 1895, the Federal Bureau of Education was operating 19 grade schools. Many were run and taught by missionaries, with these educational objectives:"Children must be kept in school until they acquire what is termed a common-school education, also practical knowledge of some useful trade. . . We believe in reclaiming the Natives from improvident habits and in transforming them into ambitious and self-helpful citizens. "Christianity was seen as a "powerful lever in influencing them to abandon their old customs. . . . " ((Darnell, 1970) .In 1900, Congress called for the District of Alaska to educate "white and colored children and children of mixed blood who live a civilized life "(Darnell, 1970) . The Secretary of Interior retained control of schools for Eskimo and American Indian children. Education continued to reflect the philosophy that Natives should be assimilated into the white culture.

Alaska became a territory in 1912. By 1917, the Territorial Legislature had established a school system, excluding Alaska Natives. The federal Bureau of Education remained responsible for the education of Alaska Natives. De facto integration was the result, since neither the territorial nor federal governments had enough money to establish separate schools throughout the Alaska Territory. Western education was the curriculum offered in both schools until 1926, when the federal schools began to include Native games and dances, and some vocational offerings. The federal government subsequently established three vocational schools for Alaska Natives at Eklutna, Kanakanak, and White Mountain.

In 1931, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) took over education of all American Indians and Alaska Natives. The BIA continued the philosophy of assimilation, though policy at the time stated that Native culture should be protected. At the end of World War II, Alaska 's Territorial Commissioner of Education proposed a single school system for Natives and non-Natives, as well as a common curriculum. The federal government rejected the proposal and retained control of Native schools. The dual federal/territorial school system resulted in a federal boarding school program for Alaska Natives that was later challenged in the famous Molly Hootch case. Discrimination was even present in determining who would attend the boarding schools:

While territorial officials undertook to provide local secondary schools for whites, the federal government had a policy of sending Native children away to boarding school. The federal policy was to acculturate Alaska Natives by sending the most intellectually advanced youths to boarding schools for a vocational education, then returning them to their villages. Most were sent to boarding schools in the Lower 48 (Ray, 1958, in Cotton, 1984. )In 1947, the BIA opened Mt. Edgecumbe boarding high school in Sitka for Natives from across Alaska. The school offered both academic and vocational curriculum. Some Alaska Native students were sent to BIA boarding schools outside Alaska if Mt. Edgecumbe was full. The BIA also operated an elementary boarding school in Wrangell.

Statehood and Molly Hootch

The BIA began to transfer operation of local schools to the Territory of Alaska in 1951. Alaska became a state in 1959 and by 1966 had created a State-Operated School System. For rural students in grades 8 through 12, the state set up several regional high schools, with the educational objective of equipping Native youth to "function in either Native or non-Native cultures "(ANC, 1994) . The state abandoned the State-Operated School System in 1975 and set up regionally controlled districts to provide for local control of schools. After the famous Molly Hootch settlement in 1976, 3 the state placed a high school in every village that had an elementary school.The 1972 class action lawsuit against the state (Hootch v. Alaska State-Operated School System, 1972) argued that Alaska's school system discriminated against Alaska Natives. The suit was based on the legal theory that the state, by failing to provide local high schools in all rural villages, was violating the education clause of Alaska's constitution, which requires the state maintain a public school system open to all children. The suit also argued that a system requiring that children leave their homes for nine months each year was not truly "open, "especially in light of the high dropout rates and severe dislocation that afflicted children in the boarding-school programs.

Known then as Tobeluk v. Lind, an out-of-court settlement was negotiated from August 1975 to October 1976. A consent decree spelled out the minimum size of high school facilities the state had to provide in each village with an elementary school. The state was obligated to provide construction costs to meet the minimum guidelines.

Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA)

While Alaska was searching for a school system that would serve all students, the young state was involved in native land claims. In 1971, Congress passed the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) , resulting in the formation of thirteen regional Native corporations. Twelve of these corporations represent Alaska 's various regions and Native groups for purposes of dispersing and managing the land and cash provided by the settlement. Natives not residing within one of the twelve regions joined the thirteenth "at-large "corporation that participated in the cash but not the land settlement.The corporations capture the cultural and geographic diversity of Alaska 's Native groups, including Aleut, Athabascan, Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Inupiat, and Yup 'ik. Each of Alaska 's Eskimo and Indian cultures speak a different language, illustrated in the following map. It is very clear that one academic curriculum - especially one designed for a non-Native Western culture - could not serve all Native children. .

Summary

Darnell's summary of the philosophy of Native education in Alaska reflects the changing federal attitude toward Native Americans:"…policy makers over the years have vacillated between attempted assimilation of the Native population into white society and protection of their cultural identity. "Alaska 's educational history mirrors that in other states, where non-Natives determined the educational policies and programs for Native students. The difficulties many Alaska Natives face in academic achievement reflect the nature of more than one hundred years of ambivalence in U. S. education policy in Alaska, and the folly of trying to assimilate rather then educate Native youth.

Current Status of Alaska Native Education:K - 12

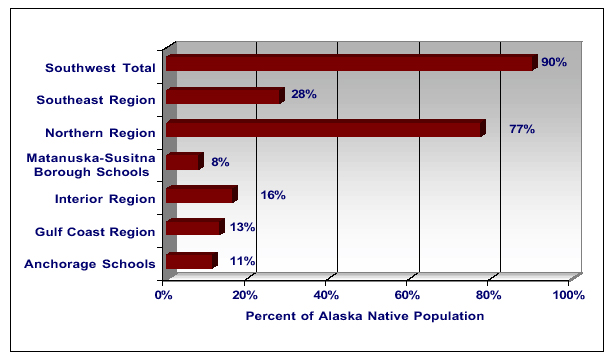

Nationwide, Native American students comprise about 1 percent of the total kindergarten to twelfth grade population 4 and 1 percent of post-secondary enrollment. 5 The total Native population is greater in Alaska, where Natives comprised nearly 23 percent of 132, 434 Alaska public school students in the current school year, 2000-01. The greatest proportion of Alaska Natives is 99 percent in the Bering Strait, St. Mary 's, Southwest Region, and Lower Yukon School Districts. Fewer than 5 percent Alaska Native students attended schools in the Skagway and Delta/Greely districts. The Native population in major urban centers ranged from 21 percent in the Juneau School District to 11 percent in both the Anchorage and Fairbanks school districts. About 90 percent of the students are Native at the state 's only regional boarding school, Mt. Edgecumbe High School in Sitka.Alaska Natives disproportionately represent more than one-third of those who drop out of school, and only about 18 percent of high school graduates. 6

Source: Alaska Department of Education and

Early Development. Compiled by McDowell Group, Inc.

Alaska Natives account for only 5 percent of public school teachers. Eighty-nine percent of Alaska 's K-12 teachers are white.

2 Created by Congress in 1990, the Alaska Natives Commission (ANC) was charged with recommending specific actions to Congress and the State of Alaska that would help assure that Alaska Natives have opportunities comparable to other Americans, while respecting their traditions, cultures, and special status as Alaska Natives. The areas of concern included self-determination, economic self-sufficiency, improved levels of educational achievement, improved health status, and reduced incidence of social problems. Alaska Native Education, Report of the Education Task Force, Alaska Natives Commission Final Report, Volume 1, Section 4, http://www.alaskool.org/resources/anc2/ANC2_Sec4.html#top.

3 The August 1972 lawsuit was filed in Superior Court in Anchorage on behalf of Native children and their parents in three Southwest Alaska villages. The first name on the list of 27 plaintiffs was Molly Hootch from Emmonak. A class action suit was then filed on behalf of all similarly situated Native children in rural villages without high schools.

4 U. S. Bureau of the Census, 1995.

5 U. S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Higher Education General Information Survey (HEGIS) , "Fall Enrollment in Colleges and Universities ";and Integrated Post-Secondary Education Data System (IPEDS) , "Fall Enrollment " surveys, , 1998-99.

6 For the school year 1998-99. Alaska Department of Education and Early Development, Report Card to the Public 1998-99, pp. 11 and 23.

Return to the Alaska Native and American Indian Education: A Review of the Literature

Return to the McDowell Final Report

Return to Alaska Native Knowledge Network