|

Sharing Our

Pathways

A newsletter of the Alaska Rural Systemic

Initiative

Alaska Federation of Natives / University

of Alaska / National Science Foundation

Volume 10, Issue 1, January/February 2005

In This Issue:

BETH LEONARD IS ORIGINALLY FROM SHAGELUK, ALASKA, a

Deg Hit'an Athabascan community on the Innoko River. Her father is James Dementi who was raised in Didlang Tochagg or Swiftwater. Her mother is the late Reverend Jean Aubrey Dementi, originally from California. Beth is married to Michael Leonard and they have one daughter, Samantha Leonard.

Beth earned her bachelor's degree in linguistics from

UAF in 1994, and a master's in educationÜlanguage & literacy,

in 1996. She is currently a Ph.D. candidate in the UAF

Interdisciplinary Studies program. Her program is based

in cross-cultural studies, Alaska Native studies and Alaska

Native languages. Beth is working on completing her dissertation

entitled "Deg Hit'an Narratives and Native Ways of Knowing."

Beth is currently an affiliate assistant professor of Athabascan,

Alaska Native

Language Center. |

Seeking Future Alaska Native PhDs!

by Ray Barnhardt and Oscar Kawagley

For over six generations, Alaska Native people have

been experiencing negative feedback in their relationships with

external systems. Though diminished and often in the background,

much of the traditional knowledge systems and world views remain

intact and in practice. There is a growing appreciation of the

contributions that indigenous knowledge can make to our contemporary

understanding in areas such as medicine, resource management, meteorology,

biology and in basic human behavior and educational practices.

Yet in order to fully benefit from these contributions, more indigenous

scholars are needed.

A quality often identified as a strength of

indigenous knowledge systems is the interconnectedness between

the parts of a system,

rather than the parts in isolation. In the study of the role

of education for indigenous people, however, attention must extend

beyond the relationships of the parts within an indigenous knowledge

system and take into account the relationships between the system

as a whole and the other external systems with which it interacts,

the most critical and pervasive being the formal structures for

knowledge production and validation imbedded in the institutions

of Western society, especially the schools.

Over a period of ten

years in the course of implementing a variety of education and

research initiatives throughout Alaska, we have

come to recognize that there is much more to be gained from further

exploring the fertile ground that exists within indigenous knowledge

systems, as well as at the intersection of converging knowledge

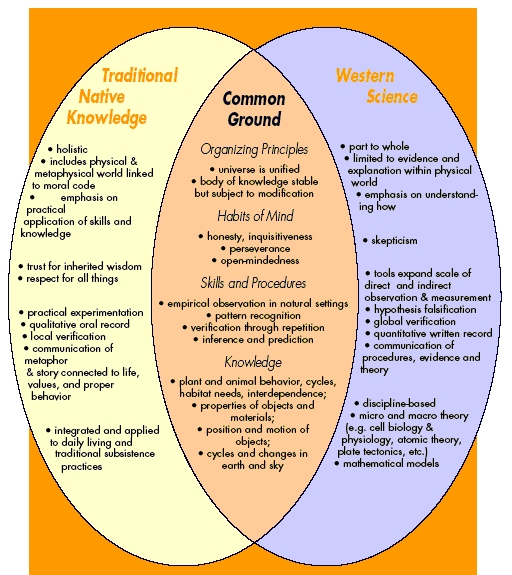

systems and world views. The following diagram captures some of

the critical elements that interrelate when indigenous knowledge

systems and Western science traditions are put side-by-side and

nudged together in an effort to derive synergistic benefits (Stephens,

2000).

From the Handbook for Culturally-Responsive Science curriculum

by Sidney Stephens, 2000. Available from the Alaska Native Knowledge

Network.

The knowledge and skills derived from thousands of

years of careful observation, scrutiny and survival in a complex

ecosystem

readily

lends itself to the in-depth study of basic principles of biology,

chemistry, physics and mathematics, particularly as they relate

to applied areas such as botany, geology, hydrology, meteorology,

astronomy, physiology, anatomy, pharmacology, technology, engineering,

ecology, topography, ornithology, fisheries and other applied

fields. Following are some of the research areas in which indigenous

knowledge and Western science have been shown to readily converge:

| Weather forecasting |

Terminology/concepts/place names |

| Animal behavior |

Counting systems/measurement/estimation |

| Navigation skills/star knowledge |

Clothing design/insulation |

| Observation skills |

Tools/technology |

| Pattern recognition |

Building design/materials/construction |

| Seasonal changes/cycles |

Transportation systems |

| Edible plants/diet/nutrition |

Genealogy |

| Food preservation/preparation |

Waste disposal |

| Rules of survival/safety |

Fire/heating/cooking |

| Medicinal plants/medical knowledge |

Hunting/fishing/trapping |

Since 1995, the Alaska Rural

Systemic Initiative has engaged in a ten-year rural school reform

effort aimed at fostering connections and complementary relationships

between the indigenous knowledge systems rooted in Alaska Native

cultures and the formal education systems imported to serve the

needs of rural Native communities. These initiatives have served

to strengthen the quality of educational experiences and improve

the academic performance of students throughout rural Alaska. The

purpose of these efforts has been to implement research-based initiatives

to systematically document the Alaska Native knowledge systems

and to develop pedagogical practices and school curricula that

incorporates this knowledge and these ways of knowing in the formal

education system. The following initiatives are the major thrusts

of the AKRSI educational reform strategy:

- Indigenous Science Knowledge

Base/Multimedia Cultural Atlas Development

- Native Ways of Knowing/

Parent Involvement

- Elders and Cultural Camps/Academy of Elders

- Village Science

Applications/Science Camps and Fairs

- Alaska Native Knowledge

Network/Cultural Resources and Web Site

- Math/Science Performance

Standards and Assessments

- Alaska Standards for Culturally Responsive

Schools

- Native Educator Associations/Leadership Development

Many of the

Native educators involved in these initiatives have concurrently

enrolled in graduate

coursework and, in response, UAF developed the new M.A. in Cross-Cultural

Studies. This degree provides opportunities for advanced study

and research on issues associated with the perpetuation of indigenous

knowledge systems in Alaska. Twenty-two Alaska Natives have completed

masters-level programs over the past five years. An equivalent

number are now enrolled in conjunction with the above activities.

One Native educator has completed an interdisciplinary Ph.D. in

Cross-Cultural Studies at UAF and three others are currently enrolled

in a doctoral program. Through the Alaska Native Knowledge Network

(www.ankn.uaf.edu) we have published numerous articles, books,

videos, CD-ROM, curriculum materials, maps and posters documenting

the outcomes of the research and development initiatives students

have

completed in conjunction with their graduate studies.

Preparing

the First Generation of Indigenous Scholars

Based on this work,

we are now seeking funding for a concerted program to prepare the

first generation of indigenous scholars

who will possess the breadth and depth of expertise to effectively

integrate indigenous and Western knowledge to the benefit of all

indigenous people as well as society as a whole.

If we are successful in securing fellowship funding, we intend

to prepare a cadre of Native scholars with the skills and understandings

to bring the two systems of thought together in a manner that promotes

a synergistic relationship whereby we begin to form a more comprehensive

and integrated understanding of the world around us, while preserving

the essential integrity of each component of this integrated system.

Students will be required to identify an area of interdisciplinary

research interest in which UAF has established faculty expertise

and for which there is an opportunity for practical application

in an existing indigenous Alaskan context. Four areas of particular

relevance in that regard are climate change, environmental contaminants,

ecological relationships and place-based education, so students

would be expected to select an initial research topic related to

one of these areas. The work of the students and faculty associated

with this program is intended to produce a two-way flow of new

insights and understandings that will serve to strengthen the knowledge

base of the university at the same time that it produces graduates

who are able to take on some of the most intractable issues across

a variety of arenas impacting Alaskan communities.

The underlying purpose of the proposed initiative focusing on integrating

indigenous knowledge and Western science is to draw upon indigenous

knowledge systems as a complement to the Western system of knowledge

in advancing our understanding of the world around us. The graduates

of the proposed program will be prepared to apply multiple lenses

in addressing the long-standing dichotomy between indigenous people

and the institutions by which they are governed. The focus of the

proposed program is to foster complimentary relationships between

two interdependent but historically divergent and complex systems—the

indigenous knowledge systems rooted in the Native cultures and

scientific research and applications associated with mainstream

institutions. In each of these systems is a rich body of knowledge

and skills that, if properly explicated and leveraged, can serve

to strengthen the quality of life for all citizens.

The proposed

program for integrating indigenous and Western knowledge is put

forward as a thematic emphasis for students enrolling in

the Interdisciplinary Ph.D. Program administered by the Graduate

School at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. UAF offers a disciplinary-based

Ph.D. program in 10 science-related areas plus mathematics, engineering

and anthropology. All other doctoral candidates enroll through

the Interdisciplinary Program and must devise an individual course

of study around an identifiable thematic area for which UAF has

appropriate expertise and resources. It is to this latter program

that this initiative is directed, as a vehicle to draw together

interdisciplinary resources and expertise that address a range

of issues that are not currently reflected in the established UAF

doctoral programs.

The proposed program would seek to establish a balance between

breadth and depth of expertise whereby all students would participate

in a common course of study associated with the broad theme of

integrating indigenous and Western knowledge, plus each student

would be required to choose an area of relevant disciplinary studies

in which they would achieve in-depth expertise. Coursework to achieve

both the breadth and depth requirements would be taken through

a combination of existing UAF and cooperating institution course

offerings, along with special seminars, distance education, visiting

scholars, international exchanges, internships and indigenous Elder’s

academies sponsored by the initiative. Recently implemented graduate

courses available through the Center for Cross-Cultural Studies

would provide the core for the thematic overview:

- CCS 601, Documenting

Indigenous Knowledge

- CCS 602, Cultural and Intellectual Property

Rights

- CCS 608, Indigenous Knowledge Systems

- CCS 612, Traditional Ecological

Knowledge

These courses would

be complemented with comparable offerings in the collaborating

disciplinary departments, plus students would

be expected to enroll for a semester or two in another indigenous-serving

institution outside of Alaska to gain further breadth and depth

of perspective. Students enrolling in a cooperating international

institution with a strong indigenous emphasis would be expected

to identify an indigenous scholar from that institution who would

serve as a member of their graduate advisory committee to help

guide the research in ways that foster cross-institutional collaboration

and comparative analysis.

A primary emphasis in the recruitment of students will be on attracting

indigenous candidates from throughout Alaska, as well as Native

Americans, Native Hawaiians and others with in-depth experience

in indigenous settings, so that the student cohort will represent

multiple cultural perspectives which can be brought to bear on

the theme of the program.

UAF faculty member Rick Caulfield accurately

articulates one of the primary incentives for initiating such a

program, which is

to address the severe shortage of Alaska Natives with advanced

degrees who can assume critical faculty roles and research responsibilities

throughout the state:

The task before us is reflected in the fact

that on UAF’s

Fairbanks campus only three percent of regular faculty are Alaska

Native or Native American. Alaska Natives make up 16% of the state’s

total population yet are severely under-represented in the ranks

of faculty. Were UAF’s Fairbanks campus to employ indigenous

faculty proportionate to the state’s population, it would

mean having over 60 indigenous faculty members rather than the

11 now employed (2000 data)

To fulfill this objective, UAF’s

Graduate School could focus on expansion of special indigenous

graduate programs across disciplines

for students in Alaska and throughout the circumpolar North. Filling

this vital niche would build a pool of potential applicants for

future faculty positions—growing capacity from within the

state and throughout the North. Proactive strategies could include

developing a bridging and mentoring program for Native graduate

education (2002).

While we have a growing list of over 40 Alaska

Native graduates with master’s degrees who are interested

in pursuing a Ph.D. program, nearly all are first generation graduates

with extensive

demands on their time and expertise. The fellowships and travel

support we are seeking for this program are essential to providing

students the opportunity to step back from day-to-day demands and

immerse themselves in their graduate studies and research so they

can complete a program in a reasonable timeframe. The intent is

to recruit two cohorts of 12 students each, with each candidate

receiving support for up to three years. In addition, we will welcome

students from other institutions who may wish to participate in

the program activities and course offerings at their own expense.

To

obtain funding and institutional support for this proposal, we

have to demonstrate that there are sufficient potential students

who would be interested in enrolling in such a program. Please

let us know if you are interested in pursuing a doctoral program

along these lines so we can add your name to our list and notify

you if we are successful in receiving the support necessary to

begin implementation. Send your expression of interest to ffrjb@uaf.edu.

Book Review: Native Voices in Research Book Review: Native Voices in Research

edited by Jill Oakes, Rick

Riewe, Alison Edmunds, Alison Dubois, and Kimberley Wilde. Aboriginal

Issues Press,

University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada (2003).

by Vivian Martindale

Every year Aboriginal Issues Press publishes a volume

of papers on subjects relating to current concerns of Aboriginal

peoples. These papers come from a variety of fields including medicine,

natural science and traditional environmental knowledge.

Although

the term “Aboriginal” is common in Canada,

in this review I have chosen to substitute the term “indigenous” for “Aboriginal” since

it is more global in nature. This particular book is divided into

five sections: Health and Education, Colonization, Ethics and Methodology,

Consultation and Public Policy and Traditional Knowledge and Planning.

The book examines the perspectives of research by and about indigenous

peoples as well as past and present social issues. Additionally

many of the contributions touch upon ethical issues in research

and the indigenous communities’ role in their own research. Although

the term “Aboriginal” is common in Canada,

in this review I have chosen to substitute the term “indigenous” for “Aboriginal” since

it is more global in nature. This particular book is divided into

five sections: Health and Education, Colonization, Ethics and Methodology,

Consultation and Public Policy and Traditional Knowledge and Planning.

The book examines the perspectives of research by and about indigenous

peoples as well as past and present social issues. Additionally

many of the contributions touch upon ethical issues in research

and the indigenous communities’ role in their own research.

In

a paper entitled, “Dentistry in Nunavut: Inuit Self-Determination

and the Politics of Health,” Carlos Quinonez examines the

historical and current structure of the dental health services

in Nunavut and how the people there are dealing with the politics

of dental treatment. In a section on traditional environmental

knowledge, Colin Gallagher writes about his experiences with the

Anishinaabe in “Quit Thinking Like a Scientist”. Gallagher’s

experience with gathering research while working with Elders is

an example of learning by working within a community. In “Storytelling

as a Methodology,” Kimberley Wilde explores the concept of

storytelling as methodology, one she utilized during her undergraduate

and graduate work. She writes about the importance of listening

to the Elders when they are telling stories and as well the importance

of storytelling to the human experience.

Another particularly engaging

article by Jay-Lynne Makinauk, Ojibway from Sagkeeng First Nation,

addresses the problems indigenous students

encounter while attending college. The article analyzes the physical,

mental, spiritual and emotional needs of the students. The author

looks at the difficulties that rural students have in adjusting

to a predominantly non-indigenous university.

The book Native

Voices in Research not only explores research issues in Canada,

it broadens its focus to include articles about

Greenland,

Bolivia, Paraguay, India and the United States. With this book,

Aboriginal Issues Press attempts to draw together the division

between outside researchers and scholars and the reality of

indigenous people themselves. From the information provided about

the authors,

10 of the total 32 authors are indigenous peoples. Although

more than half of the writers in this edition are not indigenous

peoples,

the authors all work within indigenous communities and have

expertise in their fields of study. This book is a worthwhile read

for

educators and students in the field of indigenous studies because

of its

variety of articles, by both students and professionals, who

conduct research within indigenous communities.

Teaching & Learning Through a Cultural Eye:

31st Annual BMEEC February 9-11, 2005 in Anchorage

Teaching in Alaska comes with unique blessings and

challenges. This is a region of linguistic and cultural diversity,

and is one of the only states whose second most spoken language

is of Native origin, in this instance, Yup’iit. Spanish comes

next, and the fastest growing population of English as a Second

Language (ESL) students in Anchorage schools is Hmong. In villages

and cities throughout the state, about 21 thousand elementary and

high school students speak Spanish, Russian, Tagalog or one of

a hundred other languages. How is a teacher to meet the diverse

needs of their students and the strict academic achievement requirements

of No Child Left Behind legislation?

The annual Bilingual Multicultural

Education Equity Conference, now in its 31st year, gathers hundreds

of educators, specialists,

parents, students and practitioners to share their experiences

and learn from experts. The opening address and the banquet will

feature Haida and Hmong presentations.

Bilingual education in Alaska varies from dual language instruction

with a focus almost entirely on English to Native language immersion

and language revitalization programs. At this conference, educators

learn what’s happening in their region, state and on the

national front.

With the help of a $1.4 million United States Department

of Education grant, Sealaska Heritage Institute is developing curriculum

materials

for a K–2 Haida immersion program. The director is Rosita

Worl, who will be a featured presenter. She states that in addition

to stemming the loss of Native languages, studies show language

immersion also improves student performance in other academic areas.

In addition, Elizabeth McKinley, a Maori educator from the University

of Waikato in New Zealand, will describe how the teaching of science

and mathematics is strengthened by building on cultural knowledge.

Presentations

There are presentations to suit the

needs and interests of the widest possible range of educators.

Kendra Hughes of Northwest

Regional Education Laboratory will offer a workshop in SIOP (Sheltered

English), which improves teaching and learning by focusing on content

and the language needs of second-language speaking students. Mike

Travis will also guide participants through a practical lesson

in sheltering instruction using cultural tools, standards and instructional

techniques that help English language learners. Jackie McCubrey,

an Alaska veteran and district teacher of the year, will demonstrate

the Formula 3 Reading Spelling Learning Program, in use nationally

and by 10 districts in Alaska. Jill Showman will demonstrate ways

to encourage LEP student writing and inform teachers about professional

development opportunities through the Writing Consortium.

Southwest

Region School District will demonstrate their school reform process,

aiming for coherent High Performance Learning Communities,

which involves diagnosis of schools as systems and responsiveness

to the cultural and linguistic conditions of the community. Lower

Kuskokwim School District will describe how they are integrating

standards-based education in their Yup’ik Immersion program.

Susan Paskvan will show how to combine four strands to develop

a quality Title III discretionary grant application, from professional

development in English and Native language skills to family involvement

in after school activities and seasonal language camps.

Workshops

The three-day conference, February 9 through

11, will have over 60 workshops on culturally-responsive schooling,

services to ELL

students, equity and safe schools, accountability and testing,

language development, reading strategies, staff development, student

leadership and supplemental services.

The Goals for the Conference Are:

- To increase public and professional awareness of successful

program practices in bilingual/multicultural education and share

strategies

to prepare all students to meet district and state performance

standards as required in No Child Left Behind.

- To provide an

opportunity for selected high school students to explore teacher

education, heritage language education and

to develop leadership skills.

- To address community-based strategies which enable

students to become proficient in their heritage language and

culture.

- To address educational equity issues of gender, race

and national origin in Alaska schools.

Pre-conference Events

Title III and Educator workshops

Alaska Native Educators Association charter meeting

Other events

AKABE Awards Luncheon

Installation of New AKABE Board

Student Essay Contest winners

Alaska Native Science Fair Awards

Bilingual Educator of the Year

Bilingual Program of the Year

Honoring Alaska’s Indigenous Literature Awards

For more information

or to register contact:

BMEEC /The Coordinators, Inc.

329 F Street, Suite 208

Anchorage, AK 99501

Fax (907) 646-9001

2005 Native Educator's Conference

by Linda Green and Teri Schneider

The 2005 Native Educator’s Conference will

be held concurrently with the BMEEC, including a strand of NEC

workshops and panels focusing on teaching and learning through

a cultural eye. Panelists include Elders and Native superintendents

who will provide a stimulating look at what schools and communities

are doing to implement teaching and learning strategies based on

the Alaska Standards for Culturally Responsive Schools.

The first

day (February 8, 2005) of activities will consist of a pre-conference

work session for the newly established Alaska

Native Educators Association (ANEA). Orders of business will include

election of officers, passing association bylaws, and planning

activities for the coming year. ANEA was established to assist

with the efforts of the regional Native educator associations that

have been formed over the past ten years.

A Celebration Honoring

Alaska’s

Indigenous

Literature

2005 Awards Ceremony

Tuesday, February 8, 2005

Sheraton Hotel

following the NEC

|

In the evening of February

8, the Alaska Native Educator’s

Association (ANEA) will host the annual Honoring Alaska’s

Indigenous Literature (HAIL) awards ceremony and reception at the

Sheraton Hotel. Check the NEC/BMEEC registration

desk for the specific room. Everyone is invited to join in these

events recognizing people from each region who have contributed

to the rich literary traditions of Alaska Natives

In addition, awards

for students participating in the annual Alaska Native Science

and Engineering Society statewide science fair at

Camp Carlquist on February 6–7 will be presented at the BMEEC

luncheon on February 9, 2005. The Native Science Fair is sponsored

by the Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative in collaboration with The

Imaginarium in Anchorage. All the Native Educator’s Conference

activities will be held at the Anchorage Sheraton in conjunction

with the BMEEC. For further

information you can contact Linda Green at linda@ankn.uaf.edu

or 907-474-5814. NEC/BMEEC conference registration information

and a preliminary event schedule can be viewed at: ankn.uaf.edu/bmeec.

Access Alaska: Reaching Out as a Resource for Youth with Disabilities

by Oscar Frank

Interior Alaska High School/High Tech is a model

program run by Access Alaska Incorporated that assists disabled

rural and urban Alaskan youth to prepare for work or remain in

school. High School/High Tech encourages youth who experience a

disability to enter a career in science, engineering or technology.

Access Alaska seeks positive, hopeful and culturally relevant experiences,

frequently grounded in the exploration of local resources, for

youth with personal challenges.

Students from Old Harbor and Interior

Alaska, especially Nenana, have participated in the program. During

the summer of 2003, a

Nenana youth who was jointly sponsored by Tanana Chiefs Conference

Youth Employment Services and Access Alaska, traveled to Arctic

Village for a youth leadership conference. Over 40 youth from Interior

Alaska villages participated in this conference. They spent ten

days exploring the wild and scenic country of Arctic Village and

the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), which is home to the

Gwich’in Athabascan and located in the majestic Brooks Range.

Elders, village leaders, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service personnel

and Tanana Chiefs’ staff provided sessions on the land and

water issues. There were sessions on Athabascan and Western leadership

styles. Youth learned about ANWR’s rich and fragile habitats.

One Native Elder described how to live off the land.

Access Alaska

staff also attended the 2004 Village Management Institute hosted

by Sheldon Jackson College in Sitka. Many rural parents

had questions about services for special education students and

the availability of those services and resources in rural school

districts. Most agreed parental involvement is important for their

child’s academic success.

In October 2004, Access Alaska received

four scholarships for youth to attend two conferences—Access

the Future and Wellness V—sponsored by Oregon Health and

Science University in Portland Oregon and geared towards youth

with disabilities. While there,

the Alaska youth met peers who quickly became friends and a source

of support in their efforts to pursue work and education goals

beyond high school.

Youth met Rachael Schodoris, a legally blind

19-year-old girl who grew up around sled dogs in Oregon. Ms. Schodoris,

with the aid

of a visual interpreter, is going to race the 2005 Iditarod Trail

International Sled Dog Race. She is an inspiration for all youth,

but especially those who experience a disability.

As a participant

in Access Alaska’s Department of Labor work

employment program, each youth has an Individual Service Strategy

that describes goals and objectives they personally want to achieve.

Youth prepare for work and obtain real jobs. Job readiness and

transition from school to work are key program components. Individual

youth learn job search and resume writing skills, attend job fairs,

are involved in peer counseling, participate in paid internships

and conduct Internet research.

Youth who experience a disability

are concerned about passing Alaska’s

High School Qualifying Exam (HSQE). It can be challenging for them.

High school graduation is important because many want to enter

college or go for other schooling.

Access Alaska is now exploring

ways to collaborate with Native organizations and others for mentoring

and transitioning opportunities

for youth with disabilities.

UAF is an academic resource for Access

Alaska youth and staff. Youth attend the popular Science for Alaska

series and can get

extra school credit for attending and writing about the sessions.

Last year youth and staff met a NASA scientist. Through that contact,

NASA invited Access Alaska participants to their educational conference

in Anchorage this past July.

Sharing Our Pathways newsletter assists

Access Alaska in learning about culturally-relevant educational

guidelines, programs, opportunities

and resources throughout Alaska and beyond. Elders, local leaders

and those who live a subsistence lifestyle contribute knowledge

about the lands, water and people in their area.

Rural and Native

youth who have a disability are no different than “mainstream” youth

in their dreams for a real job and higher education. They work

hard and face many challenges, but for those who are Alaska Native,

their heritage is a powerful friend as they seek to work and obtain

an education in today’s world. A chance to be employed, attend

a conference or be involved with an alternative education experience

like a leadership event is important. In these settings, youth

have an opportunity for social interaction and to learn new things,

which is often a strong motivational force for identifying and

achieving goals, particularly for youth who may experience isolation

associated with their disability.

Here is a useful website for high

school students with disabilities to prepare for college: http://www.washington.edu/doit.

If you have questions, please call:

Access Alaska. Inc.

Interior Alaska High School/

High Tech

3550 Airport Way, Suite # 3

Fairbanks, AK 99709

(907) 479-7940

Email:

ofrank@accessalaska.net

Inupiaq & Bering Strait Yupik Teachable Calendar

by Katie Bourdon

In the calendar:

Vivian Murray from

Elim. Notice the fish

hanging in the

background.

Photo from Emily

Murray. |

In hopes of sparking more interest in expressing our culture in

the classroom and at home, a group of Native educators from the

Inupiaq & Bering

Strait Yupik regions have compiled a teachable calendar for teachers

and parents. Our subsistence way of life shapes or determines our

daily activities every season. It provides a natural and relevant

means for bringing cultural life to the classroom. Preschool through

high-school teachers use a calendar for a variety of activities,

so bridging our subsistence activities and a yearly calendar makes

sense as a way to reach as many folks as possible.

Each month features

mini-lessons in various school subjects based on the traditional

harvesting activities in our communities. Quotes

from Elders and cultural experts offer advice to teachers, parents

and children. Photographs that exhibit the wonderful collection

housed at the Eskimo Heritage Program are displayed throughout

the calendar.

Family activities on the calendar encourage parents to not only

become more involved in their children’s classrooms, but

to also take pride in their cultural heritage and nurture it in

their family.

All the activities recognize the importance of our culture and

the

intelligent Native way of living life.

This is our first year completing

this calendar and suggestions, improvements and corrections are

welcomed. Calendars are $10.00

each. Please contact Kawerak Eskimo Heritage Program at 443-4386

or 443-4387

or email to ehp.pd@kawerak.org. We are truly excited about this

calendar and hope both teachers and parents embrace it. Quyanna!

In the calendar: A young girl from Gambell cutting up a young seal

while she is supervised.

Photo from EHP Collection.

Calendar

Contributors:

Emily “Funny” Murray, Elim

Luci Washington, St. Michael

Martha Stackhouse, Barrow

Polly Schaeffer, Kotzebue

Annie Conger, Nome

Dianne Schaeffer, EHP Staff

Katie Bourdon, EHP Staff

Formation of WINHEC Accreditation Authority Board of Affirmation

by Ray Barnhardt

At it’s annual meeting in Brisbane, Australia

August 2004, the Executive Board of the World Indigenous Nations

Higher Education Consortium formally accredited the following programs

offered by the Maori Wananga (Tribal Colleges) in New Zealand:

- Bachelors of Maori Law and Philosophy offered by Te Wananga

o Raukawa

- Bachelors of Teaching offered by Te Wananga o Awanuirangi

- A

Kamatua (Elders) program offered by Te Wananga o Aotearoa

Based

on that experience, a proposal (below) was put forward for consideration

to establish a standing WINHEC Accreditation Authority

Board of Affirmation and adopted by the WINHEC Executive Board

which had been serving as the Interim Board for the Accreditation

Authority.

Further information on these and other initiatives

sponsored by WINHEC, including the WINHEC Accreditation Handbook,

may be

obtained

from the WINHEC web site at www.win-hec.org, or contact Missy Lord

at the WINHEC head office

in New Zealand: missy.lord@tworotaki.ac.nz. The Accreditation Handbook

is also available on the ANKN web site at http://ankn.uaf.edu/ihe.html.

The next WINHEC Executive Board meeting is scheduled to take place

at the time of the 7th World Indigenous People’s Conference

on Education to be held in New Zealand November 26—December

1, 2005. Information on the WIPCE conference may be obtained at

http://www.wipce2005.com.

TITLE: WINHEC Accreditation Authority Board of Review

Membership

The WINHEC Accreditation Authority Board of Affirmation

shall be made up of one representative from each member indigenous

region

(currently

Aotearoa/New Zealand, Australia, Hawaii, Alaska, U.S./AIHEC

Colleges, Canada and SaamilandÜothers to be added as necessary)

to serve a five-year (staggered) term. Board of Review members

shall be nominated by the appropriate indigenous authority

in each region and approved for membership by the WINHEC

Executive Board. Where possible, Board of Review members

should have firsthand experience with indigenous-serving

programs/institutions and the WINHEC accreditation process.

Terms of Reference:

- The WINHEC Accreditation Authority Board

of Review shall be responsible to and serve at the discretion

of the WINHEC Executive

Board. The activities of the Board of Review shall be

managed through

the WINHEC Head Office and all formal actions of

the Board of Review shall be subject to approval by the

WINHEC

Executive

Board.

- The primary function of the WINHEC Accreditation

Authority Board of Review shall be to oversee the

implementation of the WINHEC accreditation review process,

including

but not limited to the following activities:

- Maintain, update and disseminate the Accreditation

Handbook and all associated materials, including formal

records of completed

accreditation

reviews.

- Establish criteria for eligibility

and procedures for reviewing applications for candidacy,

including

conducting

a preliminary site visit prior to acceptance

as a candidate

for consideration.

- Establish clear and user-friendly

guidelines for conducting a program/institutional self

study and preparing the appropriate

documentation

for an accreditation review.

- Establish guidelines

for selection,

appointment and responsibilities of the

site review

team and the process for conducting a site visit.

- Review

the report of each site review team to insure appropriate

standards have been met and submit

recommendations

to the WINHEC

Executive Board for action.

- Review and monitor

interim reports from

accredited programs/ institutions to

insure all standards and practices are maintained over

the period

of approval.

- Assist the WINHEC head office in developing

appropriate ways to recognize the quality of WINHEC-accredited

programs/

institutions

and disseminate information to bring further

credence

and

recognition

to the WINHEC accreditation process.

|

Empowering Parents

by Katie Bourdon

Recently I read an article entitled, “Raising

Children to Feel Self-Love Helps Them” by Harley Sundown,

a principal in the Lower Yukon School District. Harley wrote about

his experience of feeling loved and being important in his Yup’ik

family and, in turn, how this affected the choices he made in school

and life.

A

Gambell Elder woman demonstrating a string story. EHP Collection

photo.

The concept of loving our children seems simple and

straightforward, and therefore doing well in school should fall

into place. However,

the reality of alcohol abuse, domestic violence and sexual abuse

in our communities is staggering and affects entire families as

well as individual family members in traumatic ways. Each child

is affected differently based on his/her personality and birth

order. The loss of self-esteem, a warped self-image and feelings

of unworthiness can fester and grow within a child and be devastating.

When

a child feels bad about himself, he does not try as hard in school

as if to say, “Why fail again.” Children don’t

understand they are losing a part of themselves until they grow

older and realize that what happened was wrong and not their fault.

On the upside, technology and having access to information and

services is making a dent in this negative cycle. People who are

willing to take responsibility for themselves—past mistakes,

present problems and future choices—are changing their families’ self-esteem

and self-image. Native pride is growing and is evident in the revival

of dance and Native language in some communities. We need to increase

and continue having Native parents in the classroom and at school

to validate our children and to encourage them to try and do well.

Consistency is the key, so volunteer on a regular basis—even

a half hour a week, as long as it is every week.

Shishmaref folks at camp. EHP Collection photo.

The Eskimo Heritage

Collection documents the information shared by Elders from the

Bering Straits region during Elder conferences.

They stress the importance of keeping our language and traditions

alive, requiring cultural relevance in schools, teaching our children

Native values and passing on a subsistence way of life. Elders

have been advocating for our language and culture within the education

system for years. We are beginning to see an increase in language

immersion and cultural charter schools in our state. However, the

number of Native parents who are active in their children’s

education is still very low. Frank Hill, co-director of Alaska

Rural Systemic Initiative and former Alaska school district superintendent

says, “Parents are

the ones who can drive the school’s initiatives.”

I

don’t think we fully realize we have this power. Even if

we do know, we certainly aren’t involved enough or in significant

numbers in the PTSA or Native Parent Committees to be heard as

a strong voice. We need to encourage each other to visit our children’s

classrooms, to read to our children, to be at the school, even

for the lunch hour. Our presence makes a difference, not only in

our children’s day, but also with the whole school system.

Martha Stackhouse, Inupiaq educator, shared a comment

with me on this issue that relates to the points Harley Sundown

expressed: “The

more you hold your babies (even after they get older) the better—they

will not be spoiled from holding. It is the material goods that

spoil kids. If parents spent more time with their kids, talk to

them and play with them, they would grow up to feel important—that

they are wanted.”

Al Kookesh Steps into Senate District C

by Nancy Barnes

Outgoing Senator Georgianna

Lincoln with the new Senator

Al Kookesh, Senate District C

|

Albert Kookesh was elected to the State Senate District

C in November. He replaces Senator Georgianna Lincoln who has retired

after 14 years of service. Senate District C encompasses 250,000

square miles and is the largest senate district seat in the United

States. To give you an idea of this diverse district, it includes

126 communities, 25 school districts, 16 Native languages and covers

six Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) regional areas:

Doyon, Calista, CIRI, Ahtna, Chugach and Sealaska. Albert served

in the State House of Representatives for the past eight years,

representing House District 5, which covers Southeast

Alaska and a handful of Prince William Sound communities—Chenega,

Tatitlek and Cordova. At the 2004 Alaska Federation of Natives

Convention, he was reelected to be AFN co-chair for his

seventh year. He is Tlingit and is from Angoon, where he still

resides. Albert is a life-long subsistence hunter and fisherman.

He has been on the Sealaska Corporation Board since 1976 and is

active as the board chair. He is a trustee for the First Alaskans

Foundation, is on the executive committee (for life) for the Alaska

Native Brotherhood Grand Camp, and is the owner/ operator for Kootznoowoo

Inlet Lodge in Angoon.

Albert is married to Sally Woods-Kookesh

who teaches in Angoon. Sally is originally from Tanana. They have

five children and five

grandchildren. Albert is a graduate of Mount Edgecumbe High School.

He completed an undergraduate degree at Alaska Methodist University

and a law degree from the University of Washington.

Albert has been

a staunch supporter of quality education in rural Alaska. He says, “Rural

Alaskans want no less or no more than urban communities when it

comes to the education of our children.” When

asked how he felt about the new Alaska History graduation requirement,

Albert remarks, “I wholeheartedly support this proposal.

Our children should know about Alaska history. This is a first

step in bridging the rural and urban divide. We need to know who

we are and where we came from.”

Please feel free to contact

Senator Kookesh or his staff members, Dorothy Shockley and Nancy

Barnes, during the Alaska Legislative

Session beginning January 11, 2005. The toll free number is 1-888-288-3473.

Alaska RSI Contacts

Co-Directors

Ray Barnhardt

University of Alaska Fairbanks

ANKN/ARSI

PO Box 756730

Fairbanks, AK 99775-6730

(907) 474-1902 phone

(907) 474-5208 fax

email: ray@ankn.uaf.edu

Oscar Kawagley

University of Alaska Fairbanks

ANKN/ARSI

PO Box 756730

Fairbanks, AK 99775-6730

(907) 474-5403 phone

(907) 474-5208 fax

email: oscar@ankn.uaf.edu

Frank W. Hill

Alaska Federation of Natives

1577 C Street, Suite 300

Anchorage, AK 99501

(907) 263-9876 phone

(907) 263-9869 fax

email: frank@ankn.uaf.edu |

Regional

Coordinators

Alutiiq/Unanga{ Region:

Olga Pestrikoff, Moses Dirks & Teri Schneider

Kodiak Island Borough School District

722 Mill Bay Road

Kodiak, Alaska 99615

907-486-9276

E-mail: tschneider@kodiak.k12.ak.us

Athabascan Region:

pending at Tanana Chiefs Conference

Iñupiaq Region:

Katie Bourdon

Eskimo Heritage Program Director

Kawerak, Inc.

PO Box 948

Nome, AK 99762

(907) 443-4386

(907) 443-4452 fax

ehp.pd@kawerak.org

Southeast Region:

Andy Hope

8128 Pinewood Drive

Juneau, Alaska 99801

907-790-4406

E-mail: andy@ankn.uaf.edu

Yup’ik Region:

John Angaiak

AVCP

PO Box 219

Bethel, AK 99559

E-mail: john_angaiak@avcp.org

907-543 7423

907-543-2776 fax |

is a publication of the Alaska Rural Systemic

Initiative, funded by the National Science Foundation Division

of Educational Systemic Reform in agreement with the Alaska

Federation of Natives and the University of Alaska.

This material is based upon work supported

by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0086194.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations

expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and

do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science

Foundation.

We welcome your comments and suggestions and encourage

you to submit them to:

The Alaska Native Knowledge Network

Old University Park School, Room 158

University of Alaska Fairbanks

P.O. Box 756730

Fairbanks, AK 99775-6730

(907) 474-1902 phone

(907) 474-1957 fax

Newsletter Editor: Malinda

Chase

Layout & Design: Paula

Elmes

Up

to the contents Up

to the contents

|