|

Sharing Our

Pathways

A newsletter of the Alaska Rural Systemic

Initiative

Alaska Federation of Natives / University

of Alaska / National Science Foundation

Volume 10, Issue 2, March/April 2005

In This Issue:

HAIL Award recipients: Katherine Peter, Rita Pitka-Blumenstein,

Alisha Drabek (holding son), Marie Olson and Kari Johns

accepting for Katherine Wickersham Wade. |

2005 HAIL Celebration

Slowly rising and moving forward with the aide of

her walker, 87-year-old Katherine Peter made her way to the podium

while the presenter recited a long list of Katherine’s accomplishments.

The elder Gwich’in woman can barely see anymore, but she

flew to Anchorage to receive a 2005 Honoring Alaska’s Indigenous

Literature Award. During her acceptance speech she told the audience

that she wanted to sing them a song. It is a song made by her mother

for the Alaskan “boys” serving in World War II. She

only heard her mother sing it two or three times. The Gwich’in

lyrics call for the boys to come home and be happy. As she sings,

the audience sits mesmerized, thinking of our present and our past,

the strength of our Alaska Native Elders and the beauty of our

language and experience.

The first celebration of Alaska Native literary work

took place in 2001 following a recommendation in the Guidelines

for Respecting Cultural Knowledge. The goal was to establish a

prestigious award to honor indigenous Elders, authors, illustrators

and others who make significant contributions to the documentation

and representation of Native knowledge and traditions. Later the

celebration was renamed to Honoring Alaska’s Indigenous Literature

or HAIL.

Last month the HAIL Working Committee presented literary

awards to six individuals representing a range of talents, knowledge

and

life experience that spread across Alaska’s regions. When

Alaska Native people share, write and publish their work, which

is grounded in layers of generational and cultural knowledge, they

validate the indigenous perspective and underscore the value of

traditional knowledge.

2005 Award Winners

Katherine Peter Katherine Peter

Publication: Neets’aii Gwiindaii: Living in the Chandalar

Country

Published by the Alaska Native Language Center

University of Alaska Fairbanks

1st Edition 1992, 2nd 1993, 3rd 2001

Katherine was born in 1918

in Stevens Village located on the Yukon River in Interior Alaska.

Koyukon Athabascan was her first language.

After Katherine’s parents passed away at an early age, Chief

Esias Loola and his wife Katherine from Fort Yukon, adopted her.

In Fort Yukon she learned the Gwich’in language and grew

up in the rich Gwich’in culture. She periodically attended

the one-room Bureau of Indian Affairs school where she learned

English. In 1936 she married Steven Peter and moved to Arctic Village.

She worked briefly as a schoolteacher in Arctic Village and later

in Fort Yukon.

In 1970 she moved to Fairbanks with her family and

worked for the Alaska Native Language Center at the University

of Alaska Fairbanks.

There she taught Gwich’in and worked extensively with the

language. Katherine has composed and transcribed the largest body

of Gwich’in writing in this century. Her involvement in more

than one hundred works include translating and transcribing: texts

told to Edward Sapir in 1923 by John Fredson; Dinjii Zhuu Gwandak;

Shandaa/In My Lifetime by Belle Herbert; Khehkwaii Zheh Gwiich’i’:

Living in the Chief’s House; and numerous other stories,

narratives, legends, schoolbooks and a dictionary. She’s

retired now but still provides help with the language. In 1970 she moved to Fairbanks with her family and

worked for the Alaska Native Language Center at the University

of Alaska Fairbanks.

There she taught Gwich’in and worked extensively with the

language. Katherine has composed and transcribed the largest body

of Gwich’in writing in this century. Her involvement in more

than one hundred works include translating and transcribing: texts

told to Edward Sapir in 1923 by John Fredson; Dinjii Zhuu Gwandak;

Shandaa/In My Lifetime by Belle Herbert; Khehkwaii Zheh Gwiich’i’:

Living in the Chief’s House; and numerous other stories,

narratives, legends, schoolbooks and a dictionary. She’s

retired now but still provides help with the language.

“The contributions she has made are absolutely

amazing. Sometimes she calls early in the morning and tells me

words no longer used – archaic

words,” says Kathy Sikorski, her daughter and Gwich’in

language instructor.  Alisha Drabek Alisha Drabek

Alutiiq/Native Village of Afognak

Publication: The Red Cedar of Afognak: A Driftwind Journey

Published by the Native Village of

Afognak, 2004

Alisha Drabek is deeply connected to Kodiak and its

surrounding islands and people. She utilizes her talents of writing,

communicating

and facilitating to bring people together, share knowledge and

work towards a common good for Kodiak’s people. Writing is

her passion—she has authored many grants that have brought

thousands of dollars to the Kodiak region. Her real desire is to

write stories. The Red Cedar of Afognak, co-authored with Dr. Karen

Adams with guidance from Elder John Pestrikoff and illustrated

by Gloria Selby, is her first story. She is a talented writer and

a dedicated educator, who works endlessly to share what she has

learned.

Born and raised in Kodiak, Alisha Drabek is an assistant

professor of English at Kodiak College. She has an English and

American literature

degree and a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing, from the

University of Arizona in Tucson. She is a former tribal administrator

for the Native Village of Afognak and the founding coordinator

of Kodiak’s “Esgahluku Taquka’aq” or the

Awakening Bear cultural celebration. She is now an apprentice learning

the Alutiiq language. Alisha is married to Helm Johnson and they

have two sons.

Christopher Koonooka (Petuwaq) Christopher Koonooka (Petuwaq)

St. Lawrence Island Yupik

Publication: Ungipaghaghlanga: Let Me Tell A Story

Quutmiit Yupigita Ungipaghaatangit

Legends of the Siberian Eskimos

Published by the Alaska Native Language Center

University of Alaska Fairbanks, 2003

Christopher Koonooka, from

the community of Gambell on St. Lawrence Island, transliterated

the work of the late Georgiy A. Menovshchikov,

a Russian educator and linguist. The book, originally published

in Russian in 1988, was written in Siberian Yup’ik (with

Russian characters) and the Russian language. It features a number

of storytellers from the Chukchi area telling over 30 stories.

The Siberian Yup’ik Language is spoken by 1,000 people on

St. Lawrence Island and about the same number of people in Russia.

Mr. Koonooka “worked mostly from the original Yup’ik

and made an English version,” says Steve Jacobson, linguist

from the Alaska Native Language Center. “He made these stories

from the Russian [Siberian Yup’ik] side available to Yup’ik

people in Alaska.”

Katherine Wickersham Wade Katherine Wickersham Wade

CIRI Region, Chickaloon Village

Publication: Chickaloon Spirit

Published by the Athabascan Nation of Chickaloon

Chickaloon Village Traditional Council, 2004

Katherine Wickersham

Wade is 81 years old. She was born up the Chickaloon River, where

her aunts and grandmother delivered her.

In Chickaloon Spirit, readers learn about the adventures and challenges

this remarkable woman had in the communities of Southcentral Alaska—Chickaloon,

Sutton, Palmer, Wasilla and Anchorage—and the Matanuska River

Valley. Katherine shares what it was like to be a half-breed—not

enough Indian to be fully accepted by some of her Ahtna Indian

relatives and not enough white for some folks coming to the Valley.

Through the narrative, readers learn about mining, railroad and

highway history, along with racist encounters and Katie’s

resilience and a sense of humor in meeting life’s difficulties.

Rita Pitka-Blumenstein Rita Pitka-Blumenstein

Calista Region Yup’ik

Publication: Earth Dyes: Nuunam Qaralirkai

Published by the Institute of Alaska

Native Arts, 1983

Rita was born on a fishing boat on the ocean and

raised in Tununak, a village in Western Alaska. Rita is Yup’ik,

Athabascan, Aleut and Russian. Her mother taught her to gather

food and to

use resources from the environment for arts and crafts. She is

an expert Yup’ik basketmaker. In Earth Dyes: Nuunam Qaralirkai,

Rita shares her wealth of knowledge and experience in making natural

dyes. Rita now lives in Anchorage and works for Southcentral Foundation

as a traditional healer. In her HAIL acceptance speech, she emphasized

the importance of publishing, writing and contributing to indigenous

literature saying, “Even it [my book] is thin, it had a lot

of healing impact.”  Kaayistaan Marie Olson Kaayistaan Marie Olson

Eagle Moiety Wooshkeetaan Clan of Auke Bay

Publication: Tlingit Coloring Book

Published by Card Shark Consultant, Juneau, AK

Publication: Wild Edible & Medicinal Plants, Volumes I and

II: Alaska, Canada & Pacific Northwest Rainforest

Author: Carol R. Biggs. Published by Carol Biggs

Alaska Nature Connection, January 1999

Marie Olson of the Eagle

Moiety Wooshkeetaan Clan of Auke Bay, Alaska, provided the Tlingit

names and identified the use of a

number of plants in the Tlingit Coloring Book and Wild Edible & Medicinal

Plants, Volumes I and II. Marie Olson of the Eagle

Moiety Wooshkeetaan Clan of Auke Bay, Alaska, provided the Tlingit

names and identified the use of a

number of plants in the Tlingit Coloring Book and Wild Edible & Medicinal

Plants, Volumes I and II.

Marie works in education and is president

of Alaska Native Sisterhood Camp #2. She is a former Elder in Resident

for the Juneau School

District and instructor for the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

She shares her love of art, writing and gardening in the book Tlingit

Coloring Book. Marie was born in Juneau and spoke Tlingit in her

childhood. Her Tlingit name is Kaayistaan, which is her maternal

grandmother’s name. Marie attended school in Juneau, Seattle

and San Francisco. After raising a family she returned to school

and graduated from the University of Alaska Southeast. Marie is

widely respected for her knowledge of the Tlingit language, culture

and history.

Alaska Native Superintendents:

New Faces in School District Leadership

by Frank Hill

What’s it like to be an Alaska Native school

district superintendent working with your own people? Two Alaska

Native superintendents, Joe Slats from the Yupiit School District

and Chris Simon from the Yukon-Koyukuk School District, recently

shared their experience with participants attending the 2005 Bilingual

Multicultural Education and Equity Conference.

Joe Slats and Chris Simon

Joe and Chris think

their cultural connection to the communities they serve gives them

opportunities, expectations and challenges

other superintendents may not face. Unlike many superintendents,

Joe and Chris attended and worked in the schools in their cultural

region before being hired as superintendent. Each advanced professionally

through the school district system beginning as a teacher, next

as a principal and then to district office administration. With

this experience, training and the completion of their graduate

education, they qualified for the Alaska school superintendent

credential.

Joe Slats is Cup’ik and from Chevak, a village

located on the Niglikfak River near the Bering Sea in Southwest

Alaska, and

superintendent of the Yupiit School District serving three communities

on the Kuskokwim River. He is fluent in the two dialects of the

Central Yup’ik language: Cup’ik and Yup’ik. School

board meetings are sometimes held in Yup’ik so those attending

understand the issues discussed.

Chris Simon is Koyukon Athabascan

from Huslia, an Interior Alaska village located on the Koyukuk

River. As former Huslia School principal,

Chris remembers how he felt while walking home from work one day.

He was so happy to be serving his people he felt like he was “walking

on air.”

Joe and Chris think their district communities and

people give them a greater degree of trust than previous administrators.

They

have earned this trust through their work, their family and their

knowledge of the culture. This trust has its advantages. They are

able to address issues without having to constantly check back

with their communities.

Both expressed other rewards. People are

proud and freely discuss issues with them. They work with Elders

and have confidence they

can find solutions to the problems facing their students and schools.

They also like being a role model for Alaska Native students.

Native

superintendents not only need to satisfy their job requirements

as other superintendents do, they must also meet the high expectations

their communities and culture place on them. When school boards

work with someone from their own region, members are able to take

on policy and leadership roles quickly and consistently. Board

members and district communities know Joe and Chris are not going

to permanently leave after they retire. Getting things done right

is important. As Chris said he will live with his successes and

failures for the rest of his life.

All rural Alaska superintendents

face similar issues: inadequate funding to operate schools, dealing

with government mandates, unsatisfactory

student achievement, high teacher and administrator turnover and

other issues that take up the bulk of their time. Dealing constantly

with these issues without seeming to make much headway, may be

some of the reasons rural superintendents leave their job after

a few years. Alaska Native superintendents may get discouraged

at times, but they are already home, which means they will continue

to work on these issues long into the future.

By example, Alaska

Native superintendents are demonstrating the cultural and administrative

leadership required to help rural communities

take responsibility for Native student academic performance. Rural

Alaska’s students, parents, and communities need more dedicated

people like them.

Frank Hill is Dena’ina Athabascan born in

Iliamna, and for years worked in the school system in his cultural

region. He retired

after 19 years working for the Lake and Peninsula Borough School

District as a curriculum developer, program administrator, area

principal, assistant to the superintendent and as superintendent

the final 10 years.

Students Learn Unangan

Art and Beliefs

by Moses L. Dirks and students Elliot Aus and

Frank Nguyen

Students at Unalaska School are busy this year not

only learning to say Aang (Hi, Hello) or Slachxisaada{ malgaku{ (Is

it a nice day?) but they are also working on Unangam culture projects.

Thanks to the late Andrew Gronholdt, who reintroduced

a traditional art to the Unangan people, students are making bentwood

hats. Andrew mentored Patricia Lekanoff-Gregory and Jerah Chadwick

in this art form. Occasionally you will also see a beautifully

painted bentwood hat by Unanga{ artist Gertrude Svarny.

While

students work on their hat, they are given the freedom to express

their artist side. But they are told to respect Unanga{ art

form and keep within the patterns established by our Unanga{ forefathers.

Students learn that patience and meticulous work can bring out

products they can be proud of.

Here is what the students had to

say about their projects:

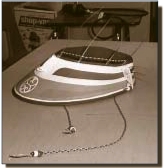

Elliot Aus’ Full Crown Bentwood

Hat

My name is Elliot Aus and my Unangan name is Quchuqi{.

I am a 12th grader at Unalaska High School. I am taking Mr. Dirks’ Aleut

Culture class. This year I made a full crown bentwood hat. I have

come a long way with this hat and am proud of it. I start with

a single piece of 24” x 24” flat Sitka spruce wood.

Then I cut the hat out from a pattern designed for the style of

hat I want. Next, I chisel out the contours and bring the thickness

down to approximately 1/8 of an inch. It takes weeks of careful

carving and chiseling to get to this point. Once done, I boil the

hat at a certain temperature to be able to bend it just right.

This is a hard procedure. One mess-up and the hat will break in

two. After it is steamed I put it into the jig, which is a wooden

form shaped like the hat, and let it dry. Once it’s dried,

I sand it down and apply oil to it. Then I put several coats of

paint on it and design it using line forms found in Unangan art.

I attach the chin strap and then it is done.

Frank Nguyen’s Unanga{ Bentwood Hat

My

name is Frank Nguyen and my Unanga{ name

is Qiiga{.

I made a short visor Aleut bentwood hat. It isn’t made from

driftwood but from Sitka Spruce milled in Fairbanks, Alaska. Beginning

hunters used this type of hat. The purpose of the visor is to keep

the sun and rainwater out of the hunter’s eyes.

The colors

represent the water. The chin straps are made of sinew. Sinew is

originally made of braided animal tendons. The whiskers

on the hat represent the prominence of the hunter. Longer sea lion

whiskers on a hat identified a better hunter. The carved ivory

amulet on top of the hat helps bring luck to the hunter.

Elliot

Aus’ full crown bentwood hat

Frank Nguyen’s Unanga{ bentwood hat.

Unalaska City School District

Southeast Place-Based Academy

by Andy Hope

The Southeast Alaska Native Educators Association

will sponsor a Place-Based Education Academy in Juneau, June 27–July

2, 2005. Information on the academy location and credit options

will be available on the ANKN events calendar. For further information,

contact Andy Hope at andy@ankn.uaf.edu or phone 907-790-9860.

The Academy will offer the following courses:

Place-Based Native

Education Resources

Instructors: Andy Hope, Dr. Ted Wright and Sean Topkok

This course

provides hands-on training in the use of the Southeast Alaska Tribal

Resource Atlas, the Southeast Alaska Tribal Electronic

Mapping Project and the Axe Handle Academy resources.

This course relates to the University of Alaska Southeast Center

for Teacher Education Conceptual Framework goals:

Goal 3: Teachers

differentiate instruction with respect for individual and cultural

characteristics.

Goal 4: Teachers possess current academic content knowledge.

Goal 7: Teachers work as partners with parents, families and the

community.

Goal 9: Teachers use technology effectively, creatively and wisely.

GIS

Workshop

Instructors: Dr. Ted Wright and Dr. Ronn Dick

This workshop is intended

for teachers and other educators to connect curriculum to the culture

and the community in more than superficial

ways. Participants will learn to use GIS mapping software and related

resources to help students create place-based projects. Participants

will practice community-based data collection that will engage

students. They will learn how to place the information in databases

that will appear as links on GIS-based maps, create curriculum

and learn to guide their students through it.

By the end of the

workshop, participants will have prepared a GIS based unit and

lesson outlines. They will have the technical and

pedagogic tools to implement a place-based curriculum in their

classrooms. They will be prepared to work with their students to

engage in projects that meet Alaska Content Standards and the Alaska

Standards for Culturally Responsive Schools.

Introduction to Tlingit

Storytelling

Instructors: Dr. Richard Dauenhauer, Nora Dauenhauer and Ishmael

Hope

The focus of this course is on the style, content

and function of Tlingit oral literature. Participants will gain

an appreciation

for the basics of Tlingit storytelling — traditional and

contemporary — and will consider ways of applying these concepts

in their personal and professional lives. The course will include

classroom reading, followed by discussions with Tlingit storytellers

of texts: Haa Shuká, Our Ancestors: Tlingit Oral Narratives

by Nora and Richard Dauenhauer; Masterworks of the Classical Haida

Mythtellers, edited and translated by Robert Bringhurst; Wisdom

Sits in Places, by Keith Basso and the working draft of Aak’wtaatseen

by Deikeenaakw.

Math in Indigenous Weaving

Instructors: Dr. Claudette Engblom-Bradley, Teri Rofkar, Janice

Criswell, Nora Dauenhauer and Steve Henrikson

This course explores

mathematics in Tlingit basketry, Chilkat blankets and Raven’s

Tail weaving through hands-on work with master basket weavers.

Students will learn weaving techniques, obtain

first-hand experience with the traditional patterns and learn to

use Ron Eglash’s Weavework Internet Software to model and

explore mathematics inherent in traditional basketry and weaving

patterns. Students will look at the Alaska Performance Standards

for Mathematics as they apply to the weaving and technology in

the curriculum. Appropriate pedagogy and assessment strategies

will be explored. Students will design, implement and assess lessons

incorporating the mathematics in Tlingit art form.

For further information,

contact Andy Hope at andy@ankn.uaf.edu or phone 790-9860.

Forming Nallunirvik: Yup'ik Literary Review in Action

by Esther Ilutsik

Annie Blue’s face glows. Her eyes dance and

twinkle with delight. Her mouth is tight, holding back laughter.

Any minute the elderly Yup’ik woman is ready to explode as

retired principal John Mark translates The Hungry Giant of the

Tundra, a children’s book written in English about the hungry

giant of the tundra. She begins to laugh when the story is finished

saying, “Oh, so great to hear a story that I heard as a child — it

brings me to that moment of my childhood when stories of this nature

were told.“ Such stories had many versions. “You must

remember that the Yup’ik region is VAST,” she adds. “So

the story that is told depends largely on where it is heard within

the region and may vary slightly.” Then she closes her eyes

and begins to tell the version of the story she heard. Occasionally

she opens her eyes and gestures with her hands and body to emphasize

a point.

This began our first Yup’ik literary review.

We have formed the Nallunirvik (A Place of Elucidation) Literary

Book Review — “we” being

a team of Yup’ik Elders and educators. Our purpose is to

read and analyze literature written about our people. Many authors

of books about Yup’ik people and life are not part of the

Yup’ik cultural region, so we carefully analyze their work

to make sure that the descriptions accurately and positively reflect

the Yup’ik culture. At our first meeting, we reviewed 20

books within a short time span of one-and one-half days, working

hard through the evenings. These reviews can be found at the Honoring

Alaska Indigenous Literature (HAIL) webpage on the ANKN website

at: http://ankn.uaf.edu/hail/. There you can access information

about the Nallunirvik Literary Book Review mission and members.

We welcome donations to help us meet again to review more books.

Quyana!

Contact:

Ayuluta Education Inc.

c/o Esther Ilutsik

PO Box 188

Dillingham, Alaska 99576

The Hungry Giant of the Tundra The Hungry Giant of the Tundra

Publisher: Dutton Children’s Book, 1993

ISBN # 0-525-45126-9

Author and Illustrator: Retold by Teri

Sloat, based on a Yup’ik

tale told by Olinka Michael, a master storyteller in the

village of Kwethluk.

Illustrated by Robert and Teri Sloat, who are married and

taught in Nunapitchuk, Kotlik, Kalskag,

Oscarville and Bethel.

Grade Level: Primary K–3

Theme: Quliraq / Traditional Yup’ik Legend

Status: Recommended

Season: Fall

Book Review

by Nallunirvik Literary

The tale retold in this book is a

quliraq or traditional legend widely known in the Yup’ik

region. It is about a giant named Aka-gua-gan-kak (the

correct Yup’ik written form

is Akaguagaankaaq) who ventures out at night looking for children

wandering about. The illustrations in the story accurately

depict the landscape where the oral tale was shared, which

is the community of Kwethluk, but the clothing the children

are wearing do not reflect the modern wooden homes shown in

the background. Instead of wearing a qaspeq, the children should

be dressed in T-shirts and windbreakers. The story flows well

and different versions of it are known throughout the Yup’ik

region.

Elder Annie Blue of Togiak has heard a different

version of the story. In her version the youngest child of

the group

is

the one able to help them escape by untying the pant legs

of the giant and calling for the crane. She yells at the

giant

and encourages him to drink from the river and has the crane

stretch his legs. As the giant attempts to cross the river

by walking on crane’s legs, the crane’s legs

begin to shake and the giant falls off. He bursts as he hits

the

bottom of the river. Annie emphasizes that other versions

of this story should be investigated at the site where the

story

is being used.

Suggested Teaching Topics:

Behavior

* Teaches children the importance of listening

to parents

* Teaches us how to be problem solvers, and indirectly,

how to behave

* Shows that everyone makes mistakes but we that can

correct our mistakes by listening to stories

Significance:

* The small bird signifies that

help can come in many forms (sizes)

* All birds are helpful, from the small songbird to

the crane

* Everyone can find a way out of a tough situation

by problem solving

* Children are well taken care of

* Be aware of what others are saying even if they

appear to be small and insignificant (even the smallest

member

of the

group can contribute to solving problems) |

ANKN Curriculum Corner

by Sean Topkok

Following is an annotated list of cultural and curriculum resources

recently added to the ANKN website. If you have questions about any

of these materials, please contact ANKN at the e-mail address listed

below.

Atkan Birds by Moses Dirks

http://ankn.uaf.edu/AtkanBirds/

In Atkan Birds Moses identifies

birds from Atka in the Unangam Tunuu and English. Unangam Tunuu,

or Atkan Aleut, is the Western

dialect

of the Aleut Language. The name, description, behavior and details

about specific bird species, along with learning activities, are

provided.

“I hope that through reading this book and doing some of

the activities that are suggested in ‘A Note to Teachers’ the

students of Atka will be able to know more about the birds that

come to

their island, and to other islands of the Aleutian Chain throughout

the

year either for the purpose of nesting or simply to avoid the long

winter months of the more northern regions of Alaska.”

— Moses Dirks in Atkan Birds

Observing Snow

sponsored by the Denali Foundation and the Alaska Rural Systemic

Initiative with help from Interior Alaska Elders

http://ankn.uaf.edu/ObservingSnow/

Observing Snow is a collaborative

effort between Western science educators and Athabascan Elders.

The curriculum is available online

and can also be ordered as a booklet with a student journal, or

on CD from ANKN. “Observing Snow is intended as a journey

to bridge the gap between the old and new, the traditional and

the scientific,

Native and Western approaches to education. … Observing Snow

is an attempt to teach basic core subjects, especially science,

and listening and reading comprehension, using materials that make

sense

to the Alaska Native student. Snow is a natural choice. Everyone

who lives in the Interior subarctic has a personal and intimate

knowledge of snow.”

— Observing Snow, page 5.

Pauline and Albert Duncan’s Tlingit Curriculum

Resources — Tlingit

Language

http://ankn.uaf.edu/Tlingit/PaulineDuncan/

Pauline and Albert

have recorded a handful of phrases, stories, early childhood songs

and rhymes. Viewers can listen to the audio

recordings

on the site. A Tlingit to English quiz is now on the page. Albert

speaks Tlingit and the listener is given four English answers

to choose from.

Introduction to Atkan Aleut Grammar and Lexicon

by Moses Dirks and Knut Bergsland

http://ankn.uaf.edu/Resources/course/view.php?id=6

This resource includes

the Elements of Atkan Aleut grammar and a junior dictionary searchable

with 4617 entries. The fonts to

display

the site need to be downloaded from a website listed on the page.

A pronunciation guide and an Aleut to English quiz are included.

The quiz displays the Aleut word or phrase with four English

answers to choose from. The questions and answers on the quiz

are random.

Sitka National Park Borhauer Basket Collection

http://ankn.uaf.edu/Resources/course/view.php?id=12

This

page has pictures of the Doris Borhauer Basket Collection by Helen

Dangel and copyrighted by the Sitka Tribe of Alaska.

Individual baskets are photographed showing details of each basket.

The written

descriptions are from the Doris’ notes.

The ANKN website

is updated continuously. To contribute to the site, please

contact the Alaska Native Knowledge Network, 907-474-5897

or uaf-cxcs@alaska.edu.

Developing Culturally Responsive School Practices in New Zealand

by Emma Stevens, Bilingual Coordinator

Southwest Region School District

Emma Stevens was born and raised in Wanganui, New

Zealand. She attended Christchurch Teachers College and spent her

five years teaching in New Zealand before traveling to England

and America. Later she returned to New Zealand and became involved

in teaching during the Maori language revival or Kohanga Reo (language

nest) movement. Her involvement in this movement sparked a teaching

passion for inclusive methodologies in education that continued

to grow when she moved to Sydney, Australia in 1988. There she

worked as an Aboriginal education representative for a school district

that introduced culturally responsive educational initiatives in

schools. Emma completed her Masters of Education at Victoria University

when she returned to New Zealand to be trained as a resource teacher

of learning and behavior. In 2002 Emma moved to Alaska with her

husband and began teaching in New Stuyahok. She is now the bilingual

coordinator for the Southwest Regional School District in Dillingham.

Five

years ago the New Zealand Educational Authority (NZEA) embarked

on a radical educational initiative to address special education

concerns surfacing in New Zealand’s schools. A disproportionate

number of Maori were classified as special education students.

Concerns included the apparent alienation of many Maori students

from their learning environments. A response to that concern was

the idea that many of these students would not be classified as

special needs if they could be taught within a learning context

that included Maori beliefs, values and practices.

The New Zealand

government initiated Special Education 2000, a call for change

that recruited 750 teachers nation wide and naming

them Resource Teachers of Learning and Behavior (RTLB). These RTLB

were trained through a two-year intensive program to work alongside

teachers, administrators, outside agencies, parents, whanau (extended

families) and iwi (tribes) to support a change in current teaching

and learning practices that would help address the growing special

education concerns.

A consortium of three New Zealand universities

developed the RTLB program. The program included intensive training

in culturally

responsive and innovative models of learning using methods proven

successful through research. The resource teachers using these

new methodologies were to retrain New Zealand educators in the

classrooms and schools. The changes that took place through these

interventions had an immediate and positive impact on teaching

practices and student outcomes.

The main elements developed to promote

culturally sensitive schools, classrooms and practices were:

1.

Ako

(reciprocal teaching, peer tutoring, modeling)

This term describes

active learning experiences and the sharing of power within the

learning process, which results in “knowledge

in action.” Peer tutoring is an example of reciprocal learning.

Peer tutoring follows traditional Maori practice for learning.

It is common for older siblings to teach younger siblings. Such

teaching strategies are effective in engaging reluctant students

since students feel culturally comfortable in the learning environment.

There are benefits to peer tutoring. Studies have shown it often

leads to academic gains for the student being tutored and the student

tutor.

Modeling is where students learn by watching, imitating

and then joining in when they feel comfortable. It was encouraged

as

an

important traditional tool that was educationally useful for acquiring

new skills. Teachers using this less confrontational teaching model

often find that shy or reluctant students are willing to try a

new skill and join in to learn something new. It is a context where

skills are practiced within a peer group and no special attention

is given to the individual. Students quickly join in and develop

a skill with little if any oral direction. The students teach each

other effectively and this promotes self-esteem and confidence

in a learning environment that is culturally familiar.

2. Group

Learning

(cooperative learning)

Maori traditional knowledge is based on sharing

and co-operation, not individual acquisition and competition. Maori

prefer groups

and easily incorporate learners at different levels. Contribution

to the physical and social well being of the group means having

individual rights and responsibilities to the group. This translates

to positive interdependence and individual accountability, which

are key components to effective cooperative learning.

Maori traditionally

have rights and responsibilities to whanau (family) and whanaungatanga

(extended family/community). Students

who become members of groups such as kapahaka (traditional dance

groups) have been shown by research to improve schoolwork and increase

academic success, self esteem and self control. If Elders assess

the effectiveness of group work, students strive to achieve mastery.

Students are not threatened by familiar Elders observing them and

are often more willing to join in. Elders use culturally appropriate

criteria for assessment such as quiet observation ensuring all

members receive care and help by others then they give oral feedback

to the group as a whole. Humor is often gently used as a tool for

more boisterous individuals to develop humility and diminish a

sense of self-importance. If such a culturally appropriate tool

is used for assessment, students are more likely to excel as an

integral and skilled member of the group.

3. Behavior Self-Management

(storytelling, power sharing, active listening, modeling)

Sharing

power allows student autonomy in developing self- managing strategies.

If students believe they are valued as an important

part of the process, they can be empowered to make choices for

which they know they are responsible. When students feel disempowered

in the management of their own behavior, there is much less motivation

to strive for improvement, especially long term. Student groups

are effective in managing group and individual behavior when they

are given specific guidelines and included as a vital part of the

process. Such self-management strategies are often more lasting

and positive than those given by authority figures.

Involving Elders

and family as members of a behavior management team can have an

impact on students. Whanau (family) involvement

can help reconcile student behavior problems through collaborative

meetings with family, Elders and the school. Students build bridges

between home and school cultures when there are reinforcements

that are consistent and meaningful to them across both contexts.

Storytelling

remains a powerful tool for transmitting sophisticated and complex

information. It allows the storyteller to define what

knowledge is created without cultural bias, and gives the listener

the ability to synthesize personal meaning. This creates a critical

link between the context and the child’s background, building

personal and powerful bridges to learning. It is through storytelling

that much of the wisdom of the group is passed down. In a listening

and oral culture the resonance of visual images and personal interaction

with the storyteller can bring meaning that remains elusive when

presented through the written word or textbook.

4. Authentic Learning

Contexts

Learning embedded in the life of the community such

as narrative pedagogy or storytelling and cultural activities,

provides

practice

for a variety of behaviors. It can prompt student motivation and

have a powerful impact on them. It validates students’ existing

knowledge and allows it to be recognized as acceptable and official.

Such positive recognition can be built upon as a student starts

to see the importance of the learning with his/ her “real” life.

Access to texts and resources that reflect a student’s life

experience build literacy skills through strong connections to

self and to the larger world. Going to school can finally become

a meaningful and engaging experience.

5. Collaboration with Parents/Families

(power sharing)

Increasing Maori participation in schools is a requirement

that can result in huge gains for all students. New Zealand’s

National Achievement Goal 1 (v) states, “in consultation

with the school’s Maori community, develop and make known

to the school’s community, policies, plans and targets for

improving the achievement of Maori students.”

When parents

and/or extended family are incorporated into the life of a school,

students recognize themselves as an integral part

of the learning environment, and education can take on a new

and profoundly personal meaning for them.

Language Revitalization

in the Inupiaq Region

by Igxubuq Dianne Schaeffer

“Uvafa

Igxubuq” = “My Inupiaq name is Igxubuq”

“Qikiqtabrubmiufurufa” = “I am from Kotzebue, now living

in Nome.”

There are many language revitalization

efforts in the Inupiaq region—from

Barrow to Nome. Some people think, “Why learn Inupiaq?

Isn’t

that taking a step backward?” Learning our first language

is actually a step forward. There is a movement across many indigenous

communities nationally and worldwide to learn our first languages

and bring them back. When you learn who you are and where you

came from and you have a strong sense of yourself.

Barrow

In Barrow, Inupiaq immersion

classes are held at the elementary school. Due to the No Child

Left Behind Act and performance

standards, the classes are now to be offered in both

Inupiaq and English.

There are plans to start an immersion school. Two Maori individuals

from New Zealand recently visited Barrow to share on their

successful shift back to their Native language. They

were inspirational

and validated Barrow’s commitment to start their own

school.

Nome

In Nome there is a group

of 15 people that meet weekly to document and learn the Wales

dialect of Inupiaq. Austin Ahmasuk initiated these informal

meetings with Elders to develop a dictionary and encourage conversational

Inupiaq in the Wales dialect. The group meets Tuesdays

5–7 p.m. at

Kawerak, although the date sometime changes.

The Eskimo

Heritage Program produced a 2005 teachable calendar,

which is geared for parents and teachers and

promotes a

cultural aspect to daily home and school life. Pictures

from the Eskimo

Heritage collection are showcased. Activities for parents

to do with their children are listed throughout the

year. Names

of the

months and days of the week are listed in the three

languages of the Bering Strait and several Inupiaq dialects.

Quotes

from past

Elder’s conferences, traditional place names,

memories of growing up traditionally, and names of

plants are

shared. The Teachable

Calendar is available from the Eskimo Heritage Program.

If you would like one please call (907) 443-4387.

The

Eskimo Heritage Program in Nome is planning to host

the Third Inupiaq and Bering Straits Yupik Education

Summit to

be held

April 25–26, 2005. Please mark your calendars

and plan to attend. We want to continue to strengthen

the ties within the Inupiaq region

and to share what we are doing in each of our Inupiaq

areas! We hope to see you here!

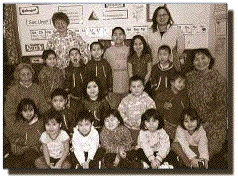

Nikaitchuat Ixisabviat 2004.

Front Row: Itiptibvik Greene,

Kaliksun Kirk, Igauqpak Fields, Avraq Erlich

and Algivak

Hanna. Second Row:

Qupaaq Schaeffer, Abbutuk Schaeffer,

Qutan Lambert, Uyaana Jones, Anaullaqtaq Hyatt

and Aana Abnik Schaeffer.

Third Row: Aana Taiyaaq

Biesemeier, Atanauraq Fields, Asaqpan Hensley,

Qaabablik Henry,

Kunuyaq Henry, Abnaqin Schaeffer

and Tusabvik Savok.

Back Row: Kunuk Lane and Nauyaq Baltazar Nikaitchuat Ixisabviat 2004.

Front Row: Itiptibvik Greene,

Kaliksun Kirk, Igauqpak Fields, Avraq Erlich

and Algivak

Hanna. Second Row:

Qupaaq Schaeffer, Abbutuk Schaeffer,

Qutan Lambert, Uyaana Jones, Anaullaqtaq Hyatt

and Aana Abnik Schaeffer.

Third Row: Aana Taiyaaq

Biesemeier, Atanauraq Fields, Asaqpan Hensley,

Qaabablik Henry,

Kunuyaq Henry, Abnaqin Schaeffer

and Tusabvik Savok.

Back Row: Kunuk Lane and Nauyaq Baltazar

Kotzebue

Nikaitchuat Ixisabviat is

midway through its seventh year. Nikaitchuat is an Inupiaq immersion

school

in Kotzebue started

by parents and

concerned community members. Nikaitchuat translates

into English as “all things are possible,” and

Ixisabviat translates

to “place of

learning.” The doors opened in September

1998.

Two dedicated teachers, Aana

Taiyaaq Biesemeier and Aana Abnik started

with the school. This is Aana

Taiyaaq’s last year;

she is retiring at the end of the school

year. Kunuk is the teacher in-training under

the

guidance of Lead Teacher Aana Abnik.

Agnatchiaq Lulu Chamblee is the current administrator

and Nauyaq Wanda Baltazar

is the administrative assistant.

Currently

Nikaitchaut is developing a pre-K to first-grade

curriculum. Curriculum developer

Jackie Nanouk and

evaluator Michael Bania

plan to have it complete by the end of

the school

year. Community members assisting with

the curriculum are:

Qutan Goodwin,

Paniyavluk Loon, Aluqtuq Sours, Aliiqataaq

Norton and others. During the

school day Elders visit regularly to talk

Inupiaq with students.

The Inupiaq Language

Task Force in Kotzebue began meeting last spring. It is made

up

of individuals

from each

organization in Kotzebue: Maniilaq, NANA,

Kotzebue IRA, Nikaitchuat,

the Northwest

Arctic Borough and School District and

the Elder’s council.

The main planners behind the task force

are Siikauraq Martha Whiting, Maamaq

Linda Joule and Salaktuna Sandy Kowalski.

The

task force

discussed reasons why Inupiaq isn’t

spoken daily and what can be done about

it. They have recommended strategies

to the Northwest

Arctic Borough School District to encourage

the use of the Inupiaq language.

Esther

Bourdon, speaking in the Wales dialect,

tells about the intestines that

her mother

prepared to

make a rain

parka. It’s

in its original bundle.

Perspectives from a LingÉt

Language Instructor

by Vivian Martindale

The following narrative with Yéilk’ Vivian

Mork was conducted and transcribed by Vivian Martindale in 2004

and edited for Sharing Our Pathways. Yéilk’is a twenty-seven-year-old

Tlingit woman from the Raven moiety and the T’akdeintaan

clan and is a full-time student at the University of Alaska Southeast

majoring in Alaska Native Studies. She is an instructor in the

Lingít language in the Dzantikí Heení Middle

School in Juneau, Alaska, and has taught at the 2003 and 2004 Kusteeyí Lingít

Immersion Camps sponsored by Sealaska Heritage Foundation.

Yéilk’ Vivian

Mork

Narrative

I decided to learn the Lingít language when

I was living in Washington State. My mother called and asked me

when

I was going

to return to Alaska to go to college. My mother was living in Hoonah

and learning the Tlingit language with local high school teacher

Duffy Wright. She was excited about it. My mother would call me

and tell me something in Lingít. She was persuasive, so

I decide to come back home. I realized I wanted to be a part of

the revitalization effort. Growing up, I was told that the language

is dead. When I found out the language wasn’t dead and that

you could learn it, I was amazed because I come from a family of

non-speakers.

In the beginning [learning the language] was important

because I knew that people weren’t learning [it]. No one

in my family spoke Lingít fluently despite the fact my grandfather

heard Lingít when he was younger. When you come from a family

with no fluent speakers, you really don’t have too many choices

about where to go in order to learn. I soon found out that they

were teaching the Lingít language at the University of Alaska

in Juneau. I decided to incorporate learning the Lingít

language into my studies. And after a couple of years of learning

the language, it has taken on a whole new life. A lot of us new

speakers feel that when we speak, we are waking up the ancestors

by using the language, giving them respect and calling on them.

When we introduce ourselves, we are telling someone in the room

who we are and calling our ancestors to stand with us.

It wasn’t

an easy transition to go from a learner to an instructor of the

Lingít language. As college students, several students

and I got better at speaking the language, and suddenly we started

to get job offers. We learned that the school system has a difficult

time hiring Elders because often an Elder doesn’t have a

degree or the skills to teach in a public school. As students we

had the credentials to offer the school, so we paired ourselves

with Elders and entered the system in that way. I’ve taught

6th, 7th and 8th grades, 4- and 5-year-olds, and college students

as well as at the community level, including Elders. It’s

scary to teach. As a learner-teacher you are aware that you don’t

know everything. You know you make mistakes, you pronounce things

wrong, and that sometimes you are going to be judged and criticized

for it. But it is important so you do it anyway. You take the criticism

and the judgment; you take it with a grain of salt and keep going.

Fortunately, when pairing a student-teacher with an Elder to teach

the language to others, we find that we learn along with the children.

In fact, we learn a lot quicker. We learn to have conversations

and we understand learning is more than memorization and commands;

it is communication flows in that environment and spills into other

areas of life. Everything becomes a teaching environment: the home,

the street and grocery store — it isn’t limited to

the school system.

For example, at the grocery store when the cashier

hands you your change, you say “Gunalcheésh.” If

they want to know what you said, you tell them that means “thank

you” in

Lingít. In fact, I was once at the Fred Meyer in Juneau

when I said “Gunalcheésh” to a cashier and she

said, “Yaa xaay yatee,” which translates loosely to

mean, “You’re welcome.” She was blond-haired,

blue-eyed and white-skinned. I never would have guessed she was

Tlingit, but it made me smile all day long. This illustrates that

you can make any experience a learning one. Most of my teaching

and learning experiences, although they have been challenging,

have been rewarding.

When I taught at the middle school I had 33

kids and 90 percent of them were boys. In the beginning, they were

rambunctious and

disrespectful. But the one thing that comes with teaching the language

is the culture; you can’t teach the language without teaching

the culture, if you want it to stick. In teaching the Tlingit language

you teach people about respect. It wasn’t long before my

class became well-behaved and even some of the most difficult kids

started being respectful. We taught the children introductions,

about their clans and the clan system, how all the Ravens and Eagles

are brothers and sisters, and the proper way to interact with one

another. I had a student who is a Teikwiedí, a brown bear.

Because the Teikwiedí is my grandmother’s people I

had to address her as my grandmother, which would make her giggle

and, more importantly, it made her interested. She listened and

a level of respect emerged between us. This young girl was 13-years-old.

Later in the summer, at [Juneau’s] Celebration, a teacher

asked this young girl what her best experience in school was. All

she talked about was the language program. She said that learning

the language is important because she felt keeping the language

alive depended on her and her fellow students. At a young age,

this girl knows the value of learning the language. She knows who

she is and her place in the web of life. I’m proud she is

one of my students.

The Tlingit class was held during the Sealaska

Heritage Institute’s

Tlingit Immersion Retreat in Hoonah last August. Yeilk was one

of the teaching interns during this program. The group ranged from

pre-school to middle school. Yéilk’ Vivian Mork holds

the ball. Students are left to right: Sophia Henry, Karoline Henry,

Harlena Sanders, Rachel White, Donnita White, Chauncey White and

Louie White.

The pride in learning your Native language is a big

change from past generations. We’ve come a long way from

the boarding-school generation who were forbidden to speak their

languages. American

boarding schools were a main contributor to the loss of language,

not just in Alaska, but also for Native cultures throughout the

United States. When you look through old government documents regarding

the boarding schools’ progress, you find references that

the government knew that in order to get rid of the “Nativeness” in

Native people, they had to remove children from their homes, out

of the culture, out of the influences, and take away their customs

and their language. Because language and culture are intertwined,

the government schools had to take it away to assimilate them.

It was almost successful.

Unfortunately, because of past policies,

there is a huge loss of the language and the knowledge that comes

with the language. It

wasn’t just the boarding-school experiences that created

the loss; it began with epidemics such as small pox and tuberculosis.

These diseases wiped out entire villages including their traditional

knowledge and language. In no time at all, whole dialects disappeared

with no possible way of getting them back. Each Elder, being a

life-long library, was gone in an instant.

There is another reason

for language loss. There were entire generations of people who

decided that the language was dead and let it go.

This came after the push to assimilate Natives into mainstream

American society. There were reasons why people went to the schools

and reasons why people sent their family members to get educated.

Native peoples knew there was a lot of change coming. They needed

to be ready and one way was to educate leaders within the Western

system. But it didn’t have to be done in such a traumatic

way. If only the American government would have known how much

better off they would have been if they allowed Native people to

keep their culture. You have groups of people living around each

other whose entire life is about taking care of each other and

they use a language system that had been indigenous to the land

for thousands of years. There is so much knowledge within the system,

and it is ridiculous to just throw it away. Intruding cultures

could have learned so much about this land, about the people. It

could have made Alaska a better place.

But we still have hope. Now

though, when we look at old videos and recordings, we hear the

Elders speak and note the differences

in the language. We realize that people who learn languages today

in a university setting differ in dialect and pronunciation from

the language learned in the villages, which is the difference between

a natural acquisition and a rather “fake” acquisition.

Despite those differences, however, it is all right to pronounce

words incorrectly when you are first learning. You have to think

of each language learner as a “child of the language.” When

they are six months into learning the language, they are six months

old.

Although the process of re-learning the language

is difficult, you notice that through learning, the students, both

young and

old, have been changed. There are people who have decided to dedicate

their lives to learning the Lingít language and have devoted

themselves to making sure it will never die. It has changed how

we language-learners relate with one another. Knowing we are going

to interact with each other for the rest of our lives, we treat

each other with respect.

When you learn the language, you begin

with a basic introduction. You learn what moiety and clan you are,

what house you are from,

and who your grandparents are. When you give that introduction

in a room full of speakers, every Elder in that room knows who

you are without having met you. This introduction can be basic

and take a few minutes to recite, but a real Tlingit introduction

can be from 10 to 20 minutes long. This is an important aspect

of the Tlingit culture. When we teach children the basic introduction,

we are teaching them who they are, who their ancestors are and

how their names and clans connect them to this land and to each

other. We teach children that they have a bigger family than the

typical nuclear American family and that we have a larger family

and a responsibility to the people around us.

Despite the lack of

natural settings to teach the Lingít

language, teaching in the school system is important. It instills

a sense of pride for Native students, especially in Juneau, since

we experience cases of racism. When children start to learn the

language, they realize where their pride can come from. We tell

them daily that they’ve been here since time immemorial and

this land is theirs—they belong to it. Another thing occurs.

People in the classroom who are not Tlingit start to ask questions

about their own ethnicity. We’ve had Yup’ik and Aleut

students in the classroom. Even a kid with Norwegian heritage was

excited about looking into his history.

We teach them they are genetically

half of their parents, and part of their grand parents and great-grandparents.

This way, children

learn that inside of them, they are literally their ancestors.

By speaking the language and by introducing themselves in Lingít,

they are respecting their ancestors by respecting themselves. The

idea of respect is something a lot of Native children don’t

have today. Gangs, media, television and music have a profound

influence on them. They are reaching out and searching for something;

they are lost. When you can teach children in their language, however,

they start to find out who they are. When they really know who

they are in the language, no one can take that away from them.

This is amazing to hold on to. It lifts their spirit and it makes

them happy and excited to come to class. They usually like the

language classes more than their mainstream classes. It makes their

spirits stronger.

Hands on Banking Teaches Money Management

In an effort to provide critically needed financial

education to students and adults nationwide, Wells Fargo & Company

has launched its newly expanded on-line financial literacy program,

Hands on Banking.Available free of charge in English or Spanish

on the Internet (www.handsonbanking.org), CDROM and in printed

curriculum, Hands on Banking teaches the basics of money management

geared to four age groups, from children to adults. In an effort to provide critically needed financial

education to students and adults nationwide, Wells Fargo & Company

has launched its newly expanded on-line financial literacy program,

Hands on Banking.Available free of charge in English or Spanish

on the Internet (www.handsonbanking.org), CDROM and in printed

curriculum, Hands on Banking teaches the basics of money management

geared to four age groups, from children to adults.

Lack of basic financial information is a serious problem among

students in public schools, which rarely offer education on personal

financial management.

“Today’s financial world is very complex

compared to what it was even ten years ago,” says Richard

Strutz, Regional President for Wells Fargo in Anchorage. “Consumers

used to maintain only checking and savings accounts, but today

they have

to understand a wide range of banking, investment and lending products.

In addition, young people too often leave high school with no working

knowledge of basic money management concepts. Hands on Banking

provides both students and adults money skills they need for life.”

In

a recent speech to the Congressional Black Caucus, Federal Reserve

Chairman Alan Greenspan stressed the pressing need for financial

education, particularly in our public schools. “Children

and teenagers should begin learning basic financial skills as early

as possible. Indeed, improving basic financial education in elementary

and secondary schools can help prevent students from making poor

decisions later, when they are young adults, that can take years

to overcome,” he said.

Designed for self-paced, individual

learning, as well as classrooms and community groups, Hands on

Banking includes topics such as

budgeting, the importance of saving, bank accounts and services,

borrowing money and establishing good credit, and investing.

The lessons are narrated, animated, colorful and contain no commercial

or promotional content. The adult curriculum includes special

sections

on managing credit, buying a home and starting and managing a

small business. The student curriculum meets or exceeds national

education

standards for math, literacy and economics and also meets the

standards of the highly respected JumpStart Coalition for Personal

Financial

Literacy.

For more information, contact Asta Keller, Wells

Fargo Community Development, at 907-265-2903 or kellera@wellsfargo.com.

Alaska RSI Contacts

Co-Directors

Ray Barnhardt

University of Alaska Fairbanks

ANKN/ARSI

PO Box 756730

Fairbanks, AK 99775-6730

(907) 474-1902 phone

(907) 474-5208 fax

email: ray@ankn.uaf.edu

Oscar Kawagley

University of Alaska Fairbanks

ANKN/ARSI

PO Box 756730

Fairbanks, AK 99775-6730

(907) 474-5403 phone

(907) 474-5208 fax

email: oscar@ankn.uaf.edu

Frank W. Hill

Alaska Federation of Natives

1577 C Street, Suite 300

Anchorage, AK 99501

(907) 263-9876 phone

(907) 263-9869 fax

email: frank@ankn.uaf.edu |

Regional

Coordinators

Alutiiq/Unanga{ Region:

Olga Pestrikoff, Moses Dirks & Teri Schneider

Kodiak Island Borough School District

722 Mill Bay Road

Kodiak, Alaska 99615

907-486-9276

E-mail: tschneider@kodiak.k12.ak.us

Athabascan Region:

pending at Tanana Chiefs Conference

Iñupiaq Region:

Katie Bourdon

Eskimo Heritage Program Director

Kawerak, Inc.

PO Box 948

Nome, AK 99762

(907) 443-4386

(907) 443-4452 fax

ehp.pd@kawerak.org

Southeast Region:

Andy Hope

8128 Pinewood Drive

Juneau, Alaska 99801

907-790-4406

E-mail: andy@ankn.uaf.edu

Yup’ik Region:

John Angaiak

AVCP

PO Box 219

Bethel, AK 99559

E-mail: john_angaiak@avcp.org

907-543 7423

907-543-2776 fax |

is a publication of the Alaska Rural Systemic

Initiative, funded by the National Science Foundation Division

of Educational Systemic Reform in agreement with the Alaska

Federation of Natives and the University of Alaska.

This material is based upon work supported

by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0086194.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations

expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and

do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science

Foundation.

We welcome your comments and suggestions and encourage

you to submit them to:

The Alaska Native Knowledge Network

Old University Park School, Room 158

University of Alaska Fairbanks

P.O. Box 756730

Fairbanks, AK 99775-6730

(907) 474-1902 phone

(907) 474-1957 fax

Newsletter Editor: Malinda

Chase

Layout & Design: Paula

Elmes

Up

to the contents Up

to the contents

|