|

Sharing Our

Pathways

A newsletter of the Alaska Rural Systemic

Initiative

Alaska Federation of Natives / University

of Alaska / National Science Foundation

Volume 10, Issue 3, Summer 2005

In This Issue:

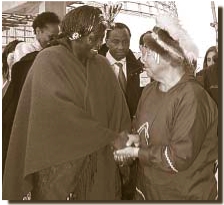

Sandra Kozevnikoff welcomes Wangari Matthai, the 2004 Nobel Peace

Prize winner from Kenya, to the Global Village at EXPO 2005. |

Pamyua, Let's Dance Again

by Mike Hull

Taiko drummers led the green dragon into the Global

Village where we watched Japanese children bring it under control

with their dances. We knew by watching the ceremony that it was

safe to welcome a special visitor. Sandra Kozevnikoff, from Russian

Mission, stepped forward to welcome Wangari Maathai, the Nobel

Peace Prize winner from Kenya, as Maathai made her entry. Sandra

and nine Yup’ik students greeted her while visiting the Global

Village at EXPO 2005 in Aichi, Japan. “The world has a lot

to learn from you,” Maathai told the Yup’ik group.

She went on to thanked them for keeping their traditions and the

wisdom they have gained from nature.

The Russian Mission group arrived

in Japan on March 15. During the next two weeks they shared their

culture, dance and an educational

program with EXPO visitors. As the Russian Mission School principal,

I had the good fortune to tag along. Russian Mission School was

the focus of a doctoral study by Takano Takako, a resident of Japan,

who is instrumental in providing outdoor educational experiences

and coordinating environmental projects for children from many

nations. Takako’s interest in the subsistence-based curriculum

of Russian Mission led to nine junior high students traveling to

Japan in 2003 to present their culture and school program at an

international symposium on the environment. The students’ performance

had such an impact on the symposium sponsors they sought to bring

Russian Mission students to Japan for EXPO 2005, with the help

of Japanese corporate sponsors. The EXPO theme is “Nature’s

Wisdom,” and the focus is on exploring ways to build sustainable

communities. This gathering of more than 80 nations and 45 international

organizations runs from March through September and will host fifteen

million visitors.

Snow flurries fell on the opening ceremonies, but these Taiko

drummers continued to perform. |

Each dance presentation ended with audience members joining

the students to learn Yup’ik dances. This was the

highlight for the visitors and students. |

During the first few days, our students presented

their dances to corporate sponsors, organizers and government officials.

These

were formal ceremonies attended by a few hundred people, and the

students provided the evening’s entertainment. At each performance,

it took them just a few minutes to get the audience to put aside

protocol and join the dancing.

The official opening of the Global

Village, the area that hosted us, took place on March 25. A delegation

of Ainu, the indigenous

people of Japan, and our Yup’ik students were first to welcome

visitors. Next the taiko drummers and a group of high profile Japanese

entertainers took the stage for the first EXPO concert. Snow flurries

throughout the day kept many visitors away, and temperatures in

the low thirties thinned the audience as the night progressed,

but those who remained started dancing to keep warm. At the end

of the last song by the Japanese performers, the audience started

chanting pamyua, the Yup’ik demand to keep dancing. The band

responded and kept playing. Other entertainers, including the taiko

drummers, returned to the stage for a spontaneous jam session.

The Yup’ik student dancers took the stage as well, and the

music went on and on. No one seemed to notice the cold any more.

The

magic continued through the week as students performed twice a

day in the Global Village. With the EXPO open to the public,

daily crowds topped sixty thousand. The Japanese are proud of their

ability to maintain a schedule, even with such numbers.

Yet once audiences were

introduced to pamyua, the ending time got pushed back further and

further. And as visitors put on headdresses

and took up dance fans, they lost all sense of time.

The Japanese

press got caught up in this Yup’ik invasion

on orderliness. A national newspaper journalist spent half-an-hour

photographing the students then he put down his camera and asked

them to teach him to dance. Our students appeared in local and

national newspapers, and the national news program featured their

presentation and interviews.

Charlotte Alexie teaches Amanda, a Singapore student, to perform

the friendship dance. |

Irene Takumjenuk teaches a young visitor to dance and two EXPO

workers take time off to follow along. |

Prior to the trip, students prepared

DVD and PowerPoint presentations that showed the subsistence activities

they participate in through

their school curriculum. The Yup’ik lifestyle presented fascinated

the Japanese and other visitors. “I think it is so cool,” said

Wazai, a high school student from Singapore. “You are able

to live so close to nature, and that is something unimaginable

for many of us.” Another student from Kyoto told our students, “We

envy the way you live and the things you do as part of your school.”

We

also received a cultural education. We stayed at a traditional

Japanese guesthouse that has large rooms covered by tatami mats

made from rice straw. We left our shoes in a storage area near

the entrance and wore slippers provided by the owners. When entering

a room covered by tatami, we left the slippers by the door. Futons

and quilts were provided for sleeping. Every night we unrolled

these on the tatami and each morning rolled them back up and put

them in the closet. We found this was a comfortable way to sleep.

Traditional Japanese meals were served in another

tatami covered room. We sat on the floor and ate a variety of foods

from

many

small dishes. I was told that eating 23 to 30 different kinds of

food a day is considered a healthy diet. We became skilled at using

chopsticks in a short time. Then there was the Japanese bath. The

guesthouse has one bath for men and one for women. Each has a common

shower area where you sit on a plastic stool while you shower.

When clean, you join friends or strangers in a pool that accommodates

several people. You soak in hot water up to your chin, and spend

an hour or longer unwinding from the day. It did not take long

to adjust to this; after the initial experience students would

run home to get in the bath. They also raced to train stations

and climbed thousands of stairs to cram into rush-hour trains.

But whether we were commuters or guests, the Japanese were forever

accommodating, gracious and interested in us.

There are many colorful

and impressive presentations from the more than 125 countries and

organizations at EXPO 2005. Yet the Yup’ik

presentation was different. The impact our students had on the

community that grew within the Global Village was beyond my comprehension.

The students not only said, “This is who we are,” they

offered the opportunity to become involved by extending the invitation: “Come

dance with us.” Affection grew between the workers at the

neighboring pavilions and our students. Our hosts took on the mischief

behaviors of their Yup’ik guests, teasing and playing in

ways that challenged Japanese protocol.

When I questioned Ohmae Junichi,

the principal sponsor for our group, about the dynamics of this

relationship he responded, “Your

students planted some sort of seeds of friendship in our community,

although the community might be a very virtual one. They are so

innocent and pure toward the world. We know these days younger

generations are so influenced by what they see on screens. Violence,

monetary richness, selfishness or opinions based on any real experiences.

Your students are really rooted into their own land, nature and

tradition. That is why they are so deeply welcomed by our villagers

who are mostly living in very artificial world.”

As our last

performance in the Global Village came to an end, representatives

from each of the pavilions came forward to thank the students for

their contribution to the spirit of EXPO 2005. There was an outpouring

of gifts and many exchanged teasing stories about their shared

experiences during the two weeks. Each group insisted that we visit

their pavilion before we departed. Goodbyes were long and tears

were shed as we left the Global Village.

Later I began to understand

that when the Japanese look to their ancestors for guidance and

wisdom they recall rice farmers. Hunters

and gatherers lie in that shadow world of prehistory and myth.

To the Japanese our Yup’ik students represented a people

older than their cultural memory. Because our students’ lives

do not lie within the scope of human activity familiar to the Japanese,

our students were like creatures of myth. Their presence reached

beyond that of mere human beings; in Yup’ik beliefs the people

share a kinship with the bear, the caribou and the other creatures

of the land. By their presence, the students showed the residents

of the Global Village that the myth lives now by saying, “Come

dance with us.” And for a few days in Japan some of the world

came together to learn from each other, and our children taught

them well.

ANKN Curriculum Corner

Holding Our Ground

http://ankn.uaf.edu/HoldingOurGround/

Holding Our Ground is

a 15-part series of half-hour radio documentaries that features

the voices of Alaska Natives as they struggle for

more control over their lives. This series aired during the fall

of 1985. Jim Sykes recorded the hearings of the Alaska Native Review

Commission (ANRC) on location in Alaska’s remote villages.

The Canadian Judge Thomas R. Berger served as commissioner for

the review and traveled throughout Alaska to find out how Alaska

Native people feel about their most basic values and how the 1971

Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act affects them. Holding Our Ground

and Judge Berger’s book, Village Journey, are the results

of the hearings. Land, subsistence and sovereignty are the main

themes that weave the people and their cultures together in a timeless

continuum. These themes are illustrated throughout the series.

This resource includes audio recordings and transcripts. Holding Our Ground is

a 15-part series of half-hour radio documentaries that features

the voices of Alaska Natives as they struggle for

more control over their lives. This series aired during the fall

of 1985. Jim Sykes recorded the hearings of the Alaska Native Review

Commission (ANRC) on location in Alaska’s remote villages.

The Canadian Judge Thomas R. Berger served as commissioner for

the review and traveled throughout Alaska to find out how Alaska

Native people feel about their most basic values and how the 1971

Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act affects them. Holding Our Ground

and Judge Berger’s book, Village Journey, are the results

of the hearings. Land, subsistence and sovereignty are the main

themes that weave the people and their cultures together in a timeless

continuum. These themes are illustrated throughout the series.

This resource includes audio recordings and transcripts.

Alaska

Sea Grant Resources

Alaska Sea Grant’s 2005 bookstore catalog

features 130 books, videos, posters and brochures designed to educate

people about

Alaska’s marine resources. Our newest book is Common Edible

Seaweeds in the Gulf of Alaska, by Dolly Garza, a Haida-Tlingit

Indian and fisheries professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Garza also wrote Tlingit Moon and Tide Teaching Resource, a curriculum

guide that brings Native understanding of science and ecology to

the elementary classroom; and an instructor manual and student

manual, which teach kids skills to help them survive in an emergency. Alaska Sea Grant’s 2005 bookstore catalog

features 130 books, videos, posters and brochures designed to educate

people about

Alaska’s marine resources. Our newest book is Common Edible

Seaweeds in the Gulf of Alaska, by Dolly Garza, a Haida-Tlingit

Indian and fisheries professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Garza also wrote Tlingit Moon and Tide Teaching Resource, a curriculum

guide that brings Native understanding of science and ecology to

the elementary classroom; and an instructor manual and student

manual, which teach kids skills to help them survive in an emergency.

Our

video Sharing the Sea: Alaska’s CDQ Program describes

the fisheries quota-sharing program, showing footage of the new

and old ways in Bering Sea coastal villages. The book The Bering

Sea and Aleutian Islands is a richly illustrated volume that tells

about the science of the Bering Sea and the people who have lived

in the region. From elementary grade curriculum guides on marine

science to cutting edge fisheries research books, the Alaska Sea

Grant has a wealth of educational materials for all ages. The Alaska

Sea Grant/Marine Advisory Program, at the University of Alaska

Fairbanks, is part of a nationwide, federal- and state-supported

program dedicated to strengthening the long-term value of marine

resources through research, education and extension.

Geophysical

Institute Library

Education materials and resources are available

at the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute

Library for K–12

classrooms. Their collection focuses on general science, geology,

space physics and Alaska Native cultures. Any teacher can check

out three items for two weeks at a time.

For more information, contact:

Geophysical Institute Library

University of Alaska Fairbanks

611 Elvey Building

P.O. Box 757320

907-474-7512

907-474-7290 fax

gilibrary@gi.alaska.edu

The Corporate Whale: ANCSA, The First 10

Years

http://ankn.uaf.edu/TheCorporateWhale/

The title and content

of this series offer an analogy between the role of the whale

in certain Alaska Native subsistence lifestyles

and the roles and responsibilities of the corporations created

under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA). The

10-part series provides audio recordings and the transcription

of the

events

leading to the ANCSA and the mechanisms employed to manage

the act. Hear how leaders assess the first 10 years and future

predictions.

Mentoring Program Helps New Teachers

by Mary Johnsen

New teacher Robyn Lamley and her class at Chief

Ivan Blunka School, New Stuyahok. Photo taken by Mentor Carol

VanDerWege.

|

Beginning teachers want to make a positive difference

in the lives of their students, but sometimes the challenges of

teaching are overwhelming. New teachers often feel frustrated,

inadequate and hopeless. A new mentoring program, the Alaska Statewide

Teacher Mentor Project (ASTMP), helps new teachers make the transition

from being a student to being in charge of a classroom.

As Lorrie

Scoles, the ASTMP program director puts it, “When

I was a beginning teacher, I knew what I wanted my classroom to

look like, feel like and sound like, but it just wasn’t coming

together. In many cases I knew what was ’right’ but

I didn’t know how to make it right. Self discovery is painful!” During

her first five years of teaching, Scoles spent her own time and

money on books, workshops and conferences. Slowly she began to

develop into the kind of teacher she wanted to be.

Key to her progress

was finding a mentor teacher to help her ask the right questions

and build on what was working. “As I

became more successful as a teacher, my students became more successful,” Scoles

explained, “I figured out how to create a community where

kids wanted to be, where they felt safe and respected. I developed

a variety of structures to keep kids challenged and accountable

for their work. It wasn’t easy!”

“That’s why I’m thrilled about

the mentor project,” said

Scoles. “Mentoring helps new teachers advance more quickly

in their profession and helps everyone feel better about what is

happening in the classroom.”

The Alaska Teacher Mentor Project

models its program after the nationally acclaimed New Teacher

Project, a program developed in

California. In this model, mentor teachers are released from

their classroom duties so they can work full time on mentoring

and they

participate in eight, week-long training programs to learn how

to help teachers analyze and improve their teaching practices.

The goal is to develop reflective teachers who are responsive

to the diverse cultural, social and linguistic backgrounds of all

students.

The project is in its first year of a two-year pilot

project sponsored by the Alaska Department of Education and Early

Development

(EED)

and the University of Alaska. EED plans to evaluate the success

of the project on improvements in student achievement and increases

in teacher retention. The department will seek ongoing funding

based on the results.

This year 37 of the 54 Alaska school districts

participated in the project. Out of a pool of 150 Alaska teachers,

22 mentors were

selected for their excellence in teaching, interpersonal skills

and experience working in urban and rural schools. They have a

combined total of 413 years of classroom teaching experience!

Each mentor works with 12 to 19 beginning teachers. The mentor

meets regularly in person, on the phone and through e-mail with

individual teachers. Mentor Jan Littlebear explains, “I model

lessons for beginning teachers, release them for observing other

teachers, bring them resources, assist in the arrangement of a

classroom or in securing supplies and resources. Together we collaborate

on planning, lessons, instruction and all areas of the profession.”

“Jan has done so much to reduce my stress in

this first year of teaching in Alaska,” said Ann Anspach,

one of Jan’s

beginning teachers at Joann A. Alexie Memorial School in the Lower

Kuskokwim School District. “She maintained a sense of humor

and helped me to do the same, even in tough times.” Ann is

grateful for the opportunity to be mentored. “We have an

experienced teacher to model teaching strategies. We have someone

to bounce ideas off of. We have someone to help us find resources

and answers. Most importantly, we have a friend who stays in regular

contact with us, and who cares about our teaching success and recognizes

that we have to be cared for as whole people, not just as teachers.”

It

has been a challenge for Director Lorrie Scoles to take the New

Teacher Center mentoring mode that was designed in California

and make it fit Alaska. One problem is travel in Alaska—weather

gets in the way.

Another issue

is helping new teachers adjust to rural Alaska. For instance, sometimes

help in the classroom takes a back seat to

helping a beginning teacher with food and housing concerns, such

as a broken hot water heater or a frozen pipe.

One central issue,

however, is mentoring new teachers about cultural differences. “How

do you teach someone to have an open mind?” asks

mentor Eric Waltenbaugh. “I would never presume to teach

about Alaska Native culture. What I can do is help teachers look

inward. Until new teachers are able to recognize their own cultural

lenses they bring to their teaching, very little movement can be

made toward adapting their teaching practice to meet the needs

of all their students. If they don’t recognize that different

forms of communication, beliefs, values and attitudes are legitimate,

they won’t see that modifying their teaching practice to

fit these differences will be helpful to both the students and

themselves.”

“Teachers have expectations regarding where

they think students should be academically, how they think students

should act, what

students should value, the best way to deliver instruction, the

most efficient way to give directions, etc.,” said Eric. “It

is very easy for a beginning teacher, given the fragility of their

first job and their need to feel successful, to judge and blame

instead of examining their own faults, misperceptions and personal

beliefs. Having a mentor helps them work out some of these thoughts

and provides positive support for professional growth.”

“For instance,” Eric explains, “New

teachers often get caught up in English literacy issues. I have

been working with

a social studies teacher who was scoring his student’s written

work based on English language standards. As part of the mentoring

process, I helped him examine his students’ work, and he

began to realize that the concepts he was teaching were getting

across. We were able to identify a high level of student thinking

that was going on. This teacher was thrilled, and empowered because

he had mistaken lack of specific language skills for lack of thinking.

This led to a discussion of whether it is fair to grade on something

you haven’t taught. The conclusion we drew was to teach specific

language skills in small chunks along with the content and evaluate

student work on these aspects alone.”

Eric tells another story

that illustrates how a mentor can bridge cultural differences.

He had dinner with several teachers that

were new to a village. He learned the teachers wanted to be involved

in the community, but were frustrated since they weren’t

invited to events or to people’s houses. Then he met with

the Elders in the community and asked them what their greatest

concerns were for the teachers in their village. The Elders replied, “The

teachers get holed up by themselves, and they need to get more

involved in the community. They need to drop by and visit with

us, take part in our activities.” Eric became a link to a

better understanding between the teachers and the community. The

new teachers learned that “dropping by” isn’t

rude; it is expected.

“Making the mentoring program more culturally

responsive is an ongoing project,” said Lorrie Scoles. “Collaborating

with Native educators to develop ways to help beginning teachers

reflect on

culture—both the culture of their students and their own—is

important work. While we have begun the dialog, there is still

much more work to be done.”

Excerpt: Mentoring the Mentor

by Jan Littlebear

Henry White, local expert, teaches third-graders from

Wm. Miller Memorial School about fish trapping in Napakiak.

Photo taken by Mentor Jan Littlebear. |

First year Yupiit instructor Elena

Miller, with the assistance of a local fish trapping expert named

Henry White, arranged

for her middle school students to make, set and check fish

traps

in the Lower Kuskokwim; and for her third graders to check

for fish

trapped in nets that had been sewn and set under the ice

near the school; and finally for the high schoolers to sew the

nets,

make

their own fish traps, set them and later check their traps

for fish. All of these wonderful traditional, cultural experiences

were taking place over the course of several weeks, ending

the

first week of December. Enter the mentor! I arrived the week

when all three classes were snowmobiling out to their sites

to check

the nets and traps for fish. Lucky me, I got to go along

for the ride. I watched as the high school students attached floater

and

lead-weight cables to fishing nets, and I went with all three

grade levels onto the frozen tundra to check set fish traps

and nets.

I traveled to Napakiak to mentor my teachers, and I received

the education!

Researching Vitamin C in Native Plants

by Candace Kruger

In 1741 Vitus Bering and his crew landed in North

America on an island in Southeast Alaska, where he exchanged goods

with the Native people living there. After setting sail for home,

he found that his men where beginning to suffer from scurvy. Scurvy

is caused from lack of vitamin C. Some of its symptoms are bleeding

gums, loss of teeth, aching joints, muscle depletion and spiraling

of the hairs on legs and arms. Bering and most of his men died

from scurvy that year. They died trying to get home from Alaska,

when all they had to do was eat some of Alaska’s native plants

to survive. Alaska has so much natural vitamin C in its vegetation.

This

year in science class students were assigned to do a project and

enter it in the school science fair. My partner, Erik Grundberg,

and I did a project on the amount of vitamin C in the plants around

our village of Anvik and in Galena, where we attend high school.

We thought the information we would learn could be useful for future

reference—in case we got sick with a cold, we would know

which plants provide the most vitamin C. According to Dr. Jerry

Gordon, on the website “How Stuff Works,” studies indicate

that a high dose of vitamin C at the beginning of a cold reduces

its symptoms in some cases. However, vitamin C does not prevent

the common cold. First we chose the plants to test: cranberries,

blueberries, rosehips, stinkweed, fireweed, spruce and yarrow.

Then we made a hypothesis:

we guessed that rosehips would have the most vitamin C. We remembered

hearing this somewhere, but we were not sure from where.

To perform

the test, we followed a procedure designed by scientists that uses

cornstarch, water and iodine. We boiled the plants individually

and extracted the juices. We mixed an iodine and cornstarch solution,

which was a dark blue-purple color. Then we added the iodine to

the juice hoping that the iodine would turn clear as it mixed.

The faster the solution turned clear would indicate the more vitamin

C in the plant.

Dr. Gordon states that the recommended dietary allowance is 60–190

milligrams of vitamin C daily to prevent a range of ailments. He

goes on to say, “Men should consume more vitamin C than women

and individuals who smoke cigarettes are encouraged to consume

35 mg more of vitamin C than the average adults. This is due to

the fact that smoking depletes vitamin C levels in the body and

is a catalyst for biological processes which damage cells.”

Gordon

explains that vitamin C is essential because it helps produce

collagen. Collagen is all over the human body. It is in cartilage,

the connective tissue of skin, bones, teeth, ligaments, the liver,

spleen and kidneys and the separating layers in cell systems

such

as the nervous system. Americans get an average of 72 mg a day.

Studies show that if the body has too high of a daily intake

of vitamin C, the worst result would be diarrhea.

To our surprise

stinkweed had the most vitamin C, with rose hips coming in second.

Our teacher, Shane Hughes, said that oranges

have little vitamin C compared to stinkweed, regardless of

the advertising that orange juice is high in vitamin C. Although

orange juice may taste a lot better, stinkweed is best when

you

need vitamin

C. You can make a tea out of it.

Candace Kruger and Erik Grundberg

examine results of vitamin C experiments.

Youth Reminds Leaders of Past Chiefs

A speech to 2005 Tanana Chiefs Conference adapted

for print

by youth delegate Tina Thomas

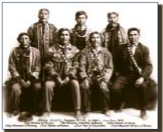

Charles

Sheldon collection, accession number 75-146-03, Archives,

Alaska and Polar Regions Department, Rasmuson

Library, University

of Alaska Fairbanks. |

This is my first year as a youth delegate, but I

have always come to these meetings. I have wondered why they never

honored the first chiefs that came to Fairbanks (Alaska) almost

90 years ago. When you walk into the Tanana Chiefs Building, in

the entryway there is a picture up on the wall. A picture of the

first chiefs

and when I look at that picture I feel pride in my heart, I feel

proud to be Native.

As I stand up here I have the jitters and I

can feel my heart pounding, but I cannot begin to imagine how the

chiefs of the Tanana River

felt, knowing that they would be talking to the white man about

our land for the very first time.

Here are a few words, according

to the archives.

The words from Chief Ivan of Crossjacket:

“You must remember that I am making this statements in the name

of the Natives, all the Natives that are in this district here.

I am making this statements because I consider that all these

Natives that I represent I am sure do not want to be put on a reservation.

They don’t want to have one and therefore I am making this

statement for the Natives I am here to represent.”

The words

from Chief Thomas of Wood River:

“I wish to especially state that when I talk to you now, I wish

to show you are touching my heart and at the same time I wish

to touch your heart.”

Judge Wickersham arose and asked the Indians:

“What do you want the United States to do for the Indians?”

Chief

Charlie of Minto replied:

“What can the United States do for us? Alaska is our home, we do

not know where our people come from, but we are the first

people here.”

Words from Chief William of Tanana:

“To give them a reservation big enough for them to live on like

they do at present would mean several hundred miles and

I don’t

think that the government can afford to give much ground.”

Replying

to the chiefs, an Alaska engineer commissioner said:

“As far as I can make out, from what the chiefs have said the Indians

want certain thing, and I want to know if I have understood

it rightly. They want freedom to come and go as they want to, fishing

and hunting, and if they take up their allotments, they

don’t

want to have to live them perhaps all the time that the

law demands, but if they do take up allotments they will build cabins and

call them their homes. Is that the opinion of the assembled

Chiefs?”

Unanimous answer from the Indians:

“Yes.”

The words of Paul Williams:

“Therefore, I wish you to take this in mind, that about this reservation,

I think it is a fake.”

With those powerful words said, I think that with the

opening of the TCC convention, we should also honor

our first chiefs,

because

without them we would not be strong, sovereign and

self-sufficient. And I will be honored to thank the

chiefs who were so

courageous and brave, for in those days it was very

hard to stand

up to the white man.

The following Indians were present

at the said council:

Chief Joe of Sakchaket

Chief John of Chena

My great, great grandfather Chief

Thomas of Wood River

Julius Pilot of Nenana

Chief Charlie of Minto

Chief Alexander of Tolovana

Titus Alexander of Tolovana

Chief Ivan of Cross jacket

Alexander William, of Ft. Gibbon

William of Ft. Gibbon

Albert of Ft. Gibbon

Jacob Starr of Ft. Gibbon

Johny Folger of Ft. Gibbon

Paul Willams of Ft. Gibbon

To these men: Basee cho (thank you).

Tina Thomas is from Toghotili

(Nenana), Alaska located on the Tanana River and the Parks Highway

in Interior

Alaska. She

is Bedzeyhti

Xut’ana, which means the Caribou Clan. Her grandmother

is Norma George and her grandfather is Charlie Thomas.

The Making of Red Cedar of Afognak

by Alisha Drabek

In August 2004, the Native Village

of Afognak Tribal Council (NVA) produced a children’s book

titled Red Cedar of Afognak: A Driftwood Journey. The book was

created through a collaboration

between Elders, Western scientists, tribal members, tribal artists

and writers. In August 2004, the Native Village

of Afognak Tribal Council (NVA) produced a children’s book

titled Red Cedar of Afognak: A Driftwood Journey. The book was

created through a collaboration

between Elders, Western scientists, tribal members, tribal artists

and writers.

The book’s production, in fact, tells a unique

story itself of how diverse groups can come together to produce

a text based

on oral tradition, with rich cultural information, in partnership

with Western science. Rooted in our Native ways of knowing, the

book is intended to be a model for sharing traditional storytelling

that incorporates scientific knowledge, with the purpose of educating

our youth in a place-based way.

The Red Cedar of Afognak was written

primarily for elementary and middle school classroom usage, as

well as within a cultural camp

context. In fact, the book project grew out of the tribe’s

Dig Afognak: Elders’ Camp where Alutiiq Elders and culture-bearers

have gathered each summer for a week to share their knowledge of

Alutiiq language, history and cultural traditions.

Left to right: Alisha Drabek, Red Cedar of Afognak co-author;

John “JP” Pestrikoff, a Port Lions Elder; and

Gloria Selby, artist and illustrator share a hug at the Port

Lions Celebration of Culture gathering to honor the book’s

publication. |

One of the Elders

who attended this camp was John Pestrikoff, “JP,” now

of Port Lions but originally from Afognak. JP shared a story his

Elders told him about a driftwood log washed a mile inland behind

the old Afognak village. His Elders told him it was thrown there

during a tsunami centuries before. He raised questions about the

long history of tsunamis in the region and their impact on the

tribe.

Among the camp participants were geologist

Dr. Gary Carver and archaeobotanist Dr. Karen Adams. Dr. Carver’s

core sample research on Afognak validated Elders’ stories

of previous tsunamis. In turn, Dr. Adams explored the origin of

driftwood varieties

and the currents on which they traveled to arrive on Afognak’s

shores. She also studied the many uses of driftwood by the Alutiiq,

who 1,000 years ago did not have trees. Dr. Adams saw JP’s

story as an excellent opportunity to demonstrate just what the

tribe’s cultural camps were trying to prove—science

concepts can be taught effectively through traditional Native knowledge.

Perhaps better said, Native knowledge is scientific.

One of the

main benefits of the book project was that combining two world

perspectives—Western science and our Native ways

of knowing—is mutually validating. The chief outcomes of

combining the two is that for Native students it helps build self-esteem

in having their Elders’ wisdom acknowledged, and makes difficult

concepts easier to grasp as they are made relevant to personal

and cultural experiences.

By acknowledging our Elders’ knowledge

we can further honor their importance in our lives as being our

first teachers. Scientific

concepts taught in school are inherently present in traditional

Native knowledge systems. Often, though, students are unaware of

the deep environmental knowledge long-existent within their culture

and families.

After Dr. Karen Adams returned home to Tucson, Arizona,

she wrote the tribe with an outline of her ideas for this book

project. The

tribal council and staff pursued the project, combining additional

oral history research they had conducted with Elders.

At the time,

I served as tribal administrator for NVA. With my background in

creative writing I developed the outline into a full

story. Working with Elders and the Alutiiq Museum, Alutiiq language

vocabulary was further incorporated into the project, as well as

graphics to demonstrate science concepts. Local tribal artist Gloria

Selby was brought in on the project after the written text was

completed. She created original watercolor artwork to accompany

the story.

In addition to the production of the book, the Native

Village of Afognak has created a companion curriculum unit. The

curriculum

outlines the potential teaching opportunities that the book supports.

They also have created a week-long culture camp to explore the

story and its concepts with youth, Elders and Native educators.

The

book has received two Honoring Alaska’s Indigenous Literature

(HAIL) awards. In February 2004 JP Pestrikoff was given a HAIL

award for his role as the contributing culture-bearer to the book.

Then, in February 2005, I received a HAIL award as the tribal author

of the book.

Copies of the book are available directly from the

Native Village of Afognak for $14.00. Contact the Native Village

of Afognak at

907-486-6357 or email vera@afognak.org.

Alisha Drabek is an assistant

professor of English at Kodiak College, a member of the Native

Educators of the Alutiiq Region

(NEAR) and

an Alutiiq language apprentice through the Alutiiq Museum.

She is an Afognak tribal member and co-author of The Red Cedar

of Afognak.

Use of Relevant Materials

Strengthens Ch'eghutsen' Project

by Hanna Carter, Cheryl Mayo-Kriska, Sarah McConnell,

Paula McQuestion and Cecelia Nation

The Ch’eghutsen’ Project is a family-driven,

culturally-appropriate and strength-based behavioral health service

for children, families

and communities. The project philosophy is founded on “ch’eghutsen’,” an

Athabascan belief from the village of Minto, Alaska that has a

broad meaning that includes “children are precious.” To

fulfill this mission, the project integrates cultural traditions,

guidance from Elders, mental health training and university credentialing.

Culturally-relevant materials shared by the Alaska Native Knowledge

Network (ANKN) are used in the project. These materials have a

significant impact on the Ch’eghutsen’s training program,

which influences the delivery of our services to children, family

and communities.

Fairbanks Native Association (FNA), Tanana Chiefs

Conference (TCC) and the University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF) collaborate

on this “System

of Care” project funded by the federal Substance Abuse and

Mental Health Services Administration. A Circles of Care grant,

which brought together Native people from Interior Alaska, guided

the development of the project’s vision, training and service

components.

Project planners identified training as an essential

component for several reasons. They hoped to develop culturally

competent

and credentialed children’s mental health providers to serve

Fairbanks and the surrounding Interior villages of Nenana, Stevens

Village, Huslia, Allakaket, Nulato and Koyukuk. They hoped to decrease

turnover by hiring and training local residents in these communities.

To decrease potential burnout of these mental health workers, they

would participate in intensive skill-based training in order to

face the challenges related to children experiencing a serious

disharmony at home, school or in the community.

The Ch’eghutsen’ Project

says “Thank you!” to

the Alaska Native Knowledge Network for your generosity and collaboration

in “sharing your pathways” with us.

The Ch’eghutsen’ Project

planners hoped to stimulate changes in the behavioral health service

system by training and

encouraging Alaska Natives to earn credentials that prepare them

to thrive in behavioral health leadership and supervisory positions.

Most of all, the planners wanted their efforts to result in culturally-appropriate

mental health services that would better meet the needs of Alaska

Native children and their families in Interior Alaska.

Staff positions

created within the Ch’eghutsen’ Project

included care coordinators, a family advocate and a youth coordinator.

Ch’eghutsen’ staff first worked through the UA Rural

Human Services Certificate Program (RHS) for training; then they

pursued the associate of applied sciences degree in Human Service.

We are thankful for the positive relationships with these programs.

Each academic program helped us meet student and project needs

with flexibility, responsiveness and cultural respect. The Ch’eghutsen’ training

program partnered with RHS and the Human Services program to develop

new UAF courses and adapt existing ones, which integrated cultural

appropriateness while maintaining academic rigor. In the development

and adaptation of courses, the ANKN materials have been highly

important.

The Ch’eghutsen’ staff, who are students,

identified cultural relevance as the essential power of the training

program.

Courses integrate community cultural traditions with mainstream

knowledge, which in turn, are valued by community members. Community

support is critical to the success of our students. Communities

share in the investment a student makes when they send an active

human resource to town for weeks of training, allowing time to

study, do homework and attend teleconference classes. In turn,

Ch’eghutsen students give back to the community by sharing

ANKN materials, using these materials to stimulate community discussion,

spark collaboration with local schools and celebrate the strengths

of their culture.

Here are a few brief examples of how we have used ANKN materials:

My

Own Trail authored by Howard Luke, was one of our main textbooks

for a Ch’eghutsen’ adapted course on rural counseling.

As part of our studies we made a day trip to Howard’s Gaalee’ya

Spirit Camp on the Tanana River. Howard Luke and Elizabeth Fleagle

were our Elder mentors for the weeklong class, bringing the book

to life. Course assignments included keeping a daily journal that

had a “trail” theme, an essay describing the student’s “own

trail” to becoming a counselor and an essay reflecting community

interviews about local descriptions and expectations of a counselor.

The

ANKN cultural values posters and cultural standards books were

key resources for the Ch’eghutsen’ developed course “Alaska

Native Healing in Human Services,” taught by Kenneth Frank

and a terrific Elder team that included Howard Luke from the Chena-Fairbanks

area, Lincoln Tritt from Arctic Village, Catherine Attla from Huslia,

Pauline Peter from Nulato and Ida Ross who is originally from Kobuk,

Alaska. Students used these materials to explore personal and community

values, discover local dormant values and develop ways to apply

cultural values and standards to their work with children and families.

The excellent resources of the Alaska Native Language Center were

also critical to the success of this course, as students learned

more about traditional stories and the applications of those stories.

Left

to right: Eliza Ned, Allakaket; Cecelia Nation, Fairbanks; Mary

Pilot, Koyukuk; Mona Perdue Jones, Fairbanks; and Sophie Ellen

Peters, Huslia.

Harold Napoleon’s Yuuyaraq: The Way of

the Human Being was a primary text in the curriculum. It is now a book

our care coordinators

recommend and talk about with Ch’eghutsen’ clients

to help them understand the powerful effects of intergenerational

trauma and to share hope with those experiencing challenging times.

As one care coordinator describes it, “I explain to them

about how our people used the old way of teaching and since we

have lost those ways, we don’t have anything to fall back

on. We don’t understand the Western way of healing and it

will not work for us. We have to go back to our Native ways of

healing, which is off the land, nature and seasons of living ...

We can learn from books like Harold Napoleon’s, because we

as Native people all have similar beliefs and customs.”

The

Gospel According to Peter John is another book that makes an impact

beyond the classroom. Information from the book is shared

with clients and the book is made available to encourage healing

that makes sense within the culture. A care coordinator said, “I

suggest that (clients) journal their thoughts and ideas and life

experiences in order to heal and put things down on paper just

like these famous authors have done. It could be a source of healing

for them and they could be authors like Harold and Peter.”

Another

participant in the Ch’eghutsen’ training program

said, “These are very critical strengthening reading materials

for me and my classmates. I would recommend sources such as these

for them to get a new meaning for our old way of life that has

pretty much disappeared from our modern day life.” There

is a true healing quality in the materials available through ANKN.

Ch’eghutsen’ now

has thirteen Alaska Native students from Fairbanks and Interior

villages who have participated in our

training program. They began their studies in the fall of 2002.

Six will receive their AAS degree in Human Service in May 2005.

Four others only need three more credits to complete their degree.

Others individuals are working towards their bachelor’s and

master’s degrees. Two have chosen to attend UAF fulltime

and are making excellent progress toward psychology degrees.

Thank

you to the Elders and community members who have supported our

training program in so many ways. Thank you to the Alaska Native

Knowledge Network for making so many helpful, culturally-relevant

materials available. We appreciate your support. It has been

important in our learning journey.

Technical Assistance for Schools in Alaska

by Ray Barnhardt

The following article contains

excerpts from the final report of the Northwest Regional Advisory

Committee submitted to the U.S.

Department of Education (DOE) on March 31, 2005.

When Congress

passed the Education Sciences Reform Act of 2002, they directed

the U.S. DOE to establish 20 technical assistance

centers to help regional, state and local educational agencies

and schools implement the No Child Left Behind goals and programs,

and apply the use of scientifically valid teaching methods and

assessment tools in:

- core academic subjects of mathematics, science and

reading or language arts;

- English language acquisition; and

- education technology.

The centers will also be responsible for:

- facilitating communication between education experts,

school officials, teachers, parents and librarians;

- disseminating

information to schools, educators, parents and policymakers for

improving academic achievement, closing achievement gaps

and encouraging and sustaining school improvement; and

- developing teacher and

school leader in-service and pre-service training models that

illustrate best practices in the use

of technology in different content areas.

They will coordinate with the regional

education labs, the National

Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, the

Office of the Secretary of Education, state service agencies

and other

technical assistance providers in the region.

DOE appointed

a committee to provide input from the Northwest region, which includes

the states of Alaska, Idaho, Montana,

Oregon and

Washington. Karen Rehfeld, from Early Education and Development,

Marilyn Davidson a Kodiak principal and Ray Barnhardt from

the University of Alaska Fairbanks were the Alaska representatives

on the Northwest Regional Advisory Committee (NW RAC). Input

to the committee was sought from educators and the general

public

throughout the state, including a two-day educational needs

assessment forum held in Anchorage in January that brought

together all

the

technical assistance providers serving Alaska schools. The

Alaskan Federation of Natives and the Southeast Regional Resource

Center

cosponsored the forum, which included representatives from

the regional Native educator associations.

Educational Challenges

Within the Region

NW RAC identified needs and developed recommendations

in four priority areas: leadership, language-culture-diversity,

closing

the achievement

gap and effective use of technology. In the area of leadership,

technical assistance in using research that improves school

leadership holds tremendous potential to help schools bolster

student academic

performance, particularly for low-income and minority students.

The

second area for technical assistance is to address issues associated

with language, culture and diversity among our students.

There

is a growing body of evidence that indicates the way language

and culture are addressed in the education system can have

a significant

impact on the performance of students, and especially those

from particular cultural communities. Culturally-responsive

curricula

and teaching practices that are tailored to the diverse populations

requires a shift in emphasis from the one-size-fits-all composite

approach that has been typical of past responses to “diversity” in

the schools.

A third area to be addressed has to do with assisting

schools in developing strategies to engage the entire community

and

establish a two-way dialogue for facilitating the achievement

of all students.

Technical assistance efforts should be focused on educating

and supporting teachers and building administrators in using

best

practices

in engaging parents as productive partners and in defining

meaningful roles for parents.

Finally, technical assistance

needs to provide support for the effective use of technology in

a school setting. The use

of technology

can also expand the reach of technical assistance centers.

It can help administrators and teachers create databases to

analyze

student

performance data to inform instructional decisions and effect

instructional improvements for the region’s diverse student

populations. In school districts where release time for teachers

is difficult

to obtain, the use of web-based technologies can improve their

access to center services. Technology permits greater access

by participants and its continuous availability enables access

to

content for even the most hard-to-reach educators. Whether

a function of geography, resource restrictions, time or knowledge,

local constraints

in addressing the challenge of developing or identifying effective

research-based practices to close the achievement gap can be

impacted through knowledgeable applications of technology.

While

the needs for technical assistance in the Northwest region

are similar to those of the rest of the country, the delivery

of technical assistance is made more challenging by the region’s

geographic vastness and subsequent population isolation. These

factors, unique to the Northwest (including Alaska), make it

difficult to create a coordinated systemic professional development

model

to build local capacity to address the academic needs of the

region’s

diverse student population. The need for well-trained and qualified

educators and effective schools within the Northwest Region

must become a priority if achievement gap disparities are to

be reduced.

Other Recommendations

The United States DOE will be

soliciting proposals from technical assistance providers outlining

how they will address the needs

identified above. In addition to a region-wide technical assistance

center, the NW RAC also recommended that a second technical

assistance center continue to be based in Alaska to specifically

deal with

issues involving Alaskan Native and American Indian students

throughout the Northwest region (with a satellite office in

Montana.)

Priorities for this center would include:

- developing and identifying culturally-appropriate research-based

materials for curriculum, learning and assessment relevant

to particular diverse populations in order to close the achievement

gap and provide

access to higher level learning opportunities for all students;

- developing

culturally-appropriate curriculum materials, teaching and assessment

practices for American Indians and Alaskan

Native students;

- identifying and disseminating research-based practices that

address the unique challenges associated with low socioeconomic

conditions;

- identifying and developing strategies for engaging families

and communities in partnership with schools to support success

for

all; and

- developing and preparing a highly effective workforce for the

culturally diverse, multi-graded, high-poverty and rural schools

of

the region.

The U.S. DOE Request for Proposals is targeted for

release in May 2005. Proposals will be submitted by early summer

and

the

new technical

assistance centers are expected to be open this fall. For

further information about the NW RAC process or recommendations,

contact:

Ray Barnhardt

(ffrjb@uaf.edu)

Karen Rehfeld

(karen_rehfeld@eed.state.ak.us)

or

Marilyn Davidson

(mdavidsonrac@kodiak.k12.ak.us)

The full report of NW RAC is available online at:

http://www.rac-ed.org/

I˝upiaq Immersion Students Learn

Language and Culture

by Martha Stackhouse

The Iñupiaq

immersion classes at the Ipalook Elementary School in Barrow are

busy learning the language and culture this

year. There are classes for three- and four-year-old children and

kindergarten and first-grade immersion classes.

When school started

in the fall, we took a field trip to the tundra to pick plants.

We picked yellow daisies, lichen, willows, tundra

leaves and tall red grass that grows along the creek. We got to

chase a lemming. Every year we go on a field trip to the beach

but polar bears roamed the beach this year so we canceled the trip.

During

the holidays, we went to the senior center to sing Christmas carols.

The students liked going there; some had an amau or “great

grandparent” in the audience. After singing, they would go

to their amau and give him or her a big hug. The senior citizens

enjoyed seeing the children in their building.

We performed for

the combined North Slope and Northwest Arctic Boroughs’ Economic

Summit, which happened prior to the Kivgiq festivities. The students

welcomed the audience in Iñupiaq,

sang songs then danced sayuutit or “motion dances,” while

one of the students drummed.

In the future, we plan to go to the

Iñupiaq Heritage Center

Museum to look at artifacts and hunting tools. In the past few

months, our children have witnessed whaling preparations in their

own homes and in the homes of their relatives. The whaling season

is always looked forward to with anticipation.

The children are

learning to count in Iñupiaq. They can

count by 10s up to 100. They are learning the Kaktovik numeral

system. The students do well in math; maybe using the Kaktovik

numeral system gives them the chance to exercise their minds and

to concentrate.

Our children are learning Iñupiaq despite

the limits with the mandated No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) we

limit Iñupiaq

language learning to 50 percent. Nevertheless, students are learning

Iñupiaq. Our teaching techniques include using Total Physical

Response. For instance, if a teacher asks a student to close the

door, the student has to say they are walking to the door and that

he or she is closing the door while doing the command. When it

is snack time, students know that they will not get juice or crackers

unless they ask for it in Iñupiaq. When students say they

are done with their work and ask to play in Iñupiaq then

they get to play.

In January we held a North Slope Education Summit.

Two people from New Zealand, Hinekahukura Tuti Aranui and Roimata

Wipiki, were

the guest speakers. They met with the language teachers, community

members and Elders. On the first day they gave the historical background

about their indigenous people and the impact that contact had in

their country, culture and language. In the 1980s they realized

their language was at risk. They started teaching their grandchildren

in their garages. They applied for grants and eventually moved

into larger buildings. As their efforts continued, the public schools

gave the hard-to-handle Maori children to the private Maori schools.

These children achieved success by graduating from high school.

Many went on to attend universities. The sense of belonging and

self-esteem moved them to a higher level. The government noticed

the success of the private Maori schools and began to fund the

schools. Today Maori language is taught through the university

level.

The next day Tuti and Roimata separated the Iñupiaq

language teachers while Jana Harcharek from the North Slope Borough

School

District met with the community. Each group came up with strategies

to keep our Iñupiaq language alive. Tuti let the teachers

vent and then asked us to dream of a perfect Iñupiaq language

school as if we were the administrators and in charge of the changes.

We decided that a private Iñupiaq Immersion school would

be best.

We would like to thank the Maori Elders for coming

to our cold climate to help us put our priorities into perspective.

The

children are learning to count in Iñupiaq. They can

count by 10s up to 100. They are learning the Kaktovik numeral

system.With No Child Left Behind, we can no longer teach total

Iñupiaq immersion. At best, we teach 50 percent Iñupiaq

and 50 percent English. English is required because they want our

schools to meet the Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP), which is measured

by testing in English. Therefore, English is being pushed in the

United States. If we are to start a private Iñupiaq Immersion

school, we would no longer be tied to NCLB.

It may be helpful for

parents to know that students taking Iñupiaq

immersion classes often do better in testing in their middle- and

high-school years. They may not do well during their elementary

school years due to not knowing English well. However, they grasp

English rapidly and later will do as well as peers who have not

taken immersion classes. In fact, most of them exceed beyond their

peers. This year former Iñupiaq immersion students won in

the middle school math competition, science fairs and the Bilingual

Multicultural Education and Equity Conference writing competition.

Their self-esteem is apparent and they are setting high expectations

for themselves.

We talked about children learning the language from

the time they are babies. The community people vowed to start teaching

Iñupiaq

to their children and grandchildren as much as possible. The young

parents, who may understand Iñupiaq but not speak it, committed

to taking Saturday classes to learn Iñupiaq. The daycare

center has shut down due to budget cuts. We discussed the possibility

of reopening it and teaching

only in Iñupiaq. This may be the starting place. Eventually

it could expand. The Paisavut Working Committee, which is a group

of Iñupiaq language teachers, has started meeting with the

Paisavut (Our Heritage) leaders to help make this dream a reality.

A Tribute to a Yup'ik Elder

by Esther Ilutsik

As a young girl, Helen Toyukak

remembers sitting in the grass near the abandoned village of Kulukak,

which was wiped out during

the 1930’s flu epidemic. She faces Qayassig or Walrus Island,

in Southwestern Alaska’s Bristol Bay region, and watches

a group of older children sitting in a circle with an Elder.

The Elder is juggling grass woven balls and chanting “Qayassiq

kan’a, Imutuq kan’ai ... ” in the Yup’ik

language. The chant ends and she continues to juggle until she

makes a mistake. A child takes the Elder’s place in the

game until each one has had a chance at this rhythmic play. As a young girl, Helen Toyukak

remembers sitting in the grass near the abandoned village of Kulukak,

which was wiped out during

the 1930’s flu epidemic. She faces Qayassig or Walrus Island,

in Southwestern Alaska’s Bristol Bay region, and watches

a group of older children sitting in a circle with an Elder.

The Elder is juggling grass woven balls and chanting “Qayassiq

kan’a, Imutuq kan’ai ... ” in the Yup’ik

language. The chant ends and she continues to juggle until she

makes a mistake. A child takes the Elder’s place in the

game until each one has had a chance at this rhythmic play.

I

would like to recognize Elder Helen “Mauvaq” Toyukak

of Manokotak for her contributions and dedication to the documentation

of traditional Yup’ik knowledge. Helen willingly and unselfishly

shared her knowledge about grass baskets, the raiding of mouse

food caches and the traditional fancy squirrel parka. The knowledge

base that she shared is used by many of our Bristol Bay area teachers

and instructors in the classroom and at the university. Quyana

cakneq!

Alaska RSI Contacts

Co-Directors

Ray Barnhardt

University of Alaska Fairbanks

ANKN/ARSI

PO Box 756730

Fairbanks, AK 99775-6730

(907) 474-1902 phone

(907) 474-5208 fax

email: ray@ankn.uaf.edu

Oscar Kawagley

University of Alaska Fairbanks

ANKN/ARSI

PO Box 756730

Fairbanks, AK 99775-6730

(907) 474-5403 phone

(907) 474-5208 fax

email: oscar@ankn.uaf.edu

Frank W. Hill

Alaska Federation of Natives

1577 C Street, Suite 300

Anchorage, AK 99501

(907) 263-9876 phone

(907) 263-9869 fax

email: frank@ankn.uaf.edu |

Regional

Coordinators

Alutiiq/Unanga{ Region:

Olga Pestrikoff, Moses Dirks & Teri Schneider

Kodiak Island Borough School District

722 Mill Bay Road

Kodiak, Alaska 99615

907-486-9276

E-mail: tschneider@kodiak.k12.ak.us

Athabascan Region:

pending at Tanana Chiefs Conference

Iñupiaq Region:

Katie Bourdon

Eskimo Heritage Program Director

Kawerak, Inc.

PO Box 948

Nome, AK 99762

(907) 443-4386

(907) 443-4452 fax

ehp.pd@kawerak.org

Southeast Region:

Andy Hope

8128 Pinewood Drive

Juneau, Alaska 99801

907-790-4406

E-mail: andy@ankn.uaf.edu

Yup’ik Region:

John Angaiak

AVCP

PO Box 219

Bethel, AK 99559

E-mail: john_angaiak@avcp.org

907-543 7423

907-543-2776 fax |

is a publication of the Alaska Rural Systemic

Initiative, funded by the National Science Foundation Division

of Educational Systemic Reform in agreement with the Alaska

Federation of Natives and the University of Alaska.

This material is based upon work supported

by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0086194.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations

expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and

do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science

Foundation.

We welcome your comments and suggestions and encourage

you to submit them to:

The Alaska Native Knowledge Network

Old University Park School, Room 158

University of Alaska Fairbanks

P.O. Box 756730

Fairbanks, AK 99775-6730

(907) 474-1902 phone

(907) 474-1957 fax

Newsletter Editor: Malinda

Chase

Layout & Design: Paula

Elmes

Up

to the contents Up

to the contents

|