|

|

|

|

Sharing Our

Pathways

A newsletter of the Alaska Rural Systemic

Initiative

Alaska Federation of Natives / University

of Alaska / National Science Foundation

Volume 9, Issue 2, March/April 2004

In This Issue:

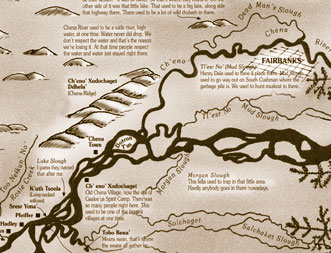

A portion of the traditional map included with Howard Luke: My

Own Trail

|

Blowing in the Wind

by Angayuqaq Oscar Kawagley

There are messages for us, as a Native people,

blowing in the wind that are older than any of our Native languages.

I think one message is telling us that we can make change for

the better in our lives through dedication, motivation, tenacity

and traditional creativity to overcome the limitations of the

current education system. This means that we educate our Native

people in their Native languages and English to become articulate

in both. This will enable them to think in their own worldviews

for answers to their problems and exercise the means of control

of the modern world to clearly and effectively articulate demands

for change.

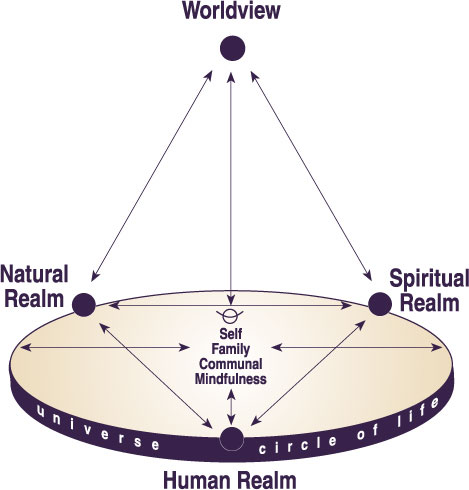

I use the tetrahedral metaphor as a way of trying

to explain the synergistic process of keeping balance in ones

life. The base is a triangle with the human, natural and spiritual

worlds as the foundation of the worldview. I have read a book

which analyzes the number three as a "breaking through to

a world of infinite possibilities" (Brailsford, 1999). He

further points out that three symbolizes creation and that one

and two are the parents of number 3, the first born. If I think

of it in this manner then the triune God of the Bible comes into

mind. For the tetrahedral, it is the spiritual power that is

eternal and omnipresent. Mother Earth is created and from its

rocks comes all life, including the human being, thus serving

as the basis of all life. This process presents infinite possibilities

of solutions for overcoming a mechanical worldview that is so

destructive to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. It

then behooves the Native people to pursue education diligently

in their own thought world as well as in the disciplines of the

modern world. This enables Native people to use their own problem-solving

tools as well as those of the mechanical world to effect change.

I

have often said and heard that sense of place serves as the basis

for identity and a home for the mind and heart. In some schools,

students have been engaged in cultural mapping activities to

identify the Native geographic names associated with the features

of a particular place. This gives a cultural grid to place over

the land, that provides order, meaning and stability to those

who live on that land. To know place is to know oneself, which

empowers us to do things with courage and determination. I

have often said and heard that sense of place serves as the basis

for identity and a home for the mind and heart. In some schools,

students have been engaged in cultural mapping activities to

identify the Native geographic names associated with the features

of a particular place. This gives a cultural grid to place over

the land, that provides order, meaning and stability to those

who live on that land. To know place is to know oneself, which

empowers us to do things with courage and determination.

I have experienced a process in New Zealand whereby

Maori Elders were taken to landmarks of the Waikato traditional

lands. They were reviewing a booklet that had been prepared citing

important places, what had transpired there and myths associated

with that place. A guide was appointed who gave a running dialogue

of points of interest and what was known about them, which the

Elders then critiqued. The process was very constructive as it

entailed correction of pronunciation of place names and added

information to what was already known that sometimes led to significant

revisions to the name and what actually happened there. This

authentication process is needed as the Maori want to rewrite

their history, not from the point of view of an outsider, but

from within.

Wouldn't it be advisable for Alaska Native people

to engage in a similar process? For urban areas such as Fairbanks,

a group of knowledgeable Native Elders could be taken to various

historical sites whereby the traditional Native name is given

and the story told as to its use, occupancy, burial places of

leaders, old migration trails, battle skirmishes, peacemaking,

kinship, alliances, particular resources and so forth. All this

information would be recorded by video and audio tape, transcribed

and edited and later the Elders would again gather to piece together

a story acceptable to all. Some beginning examples of this are

already available, such as the Minto Mapping Project (ankn.uaf.edu/chei/mapproj.html),

the Angoon Cultural Atlas (www.ankn.uaf.edu) and the traditional

map and book assembled by Howard Luke (Luke, 1999).

I can foresee a caravan of snow machines transporting

Elders to different areas such as camp sites, places of warrior

skirmishes, hunting grounds and burial places where the correct

name and what transpired there would be clarified. In the summer,

boats loaded with Elders could be taken to significant sites

agreed upon to tell their stories. I can envision a bus full

of Elders slowly going around Bethel recounting the old sites

of fish camps, the kasegiq, the original location of

Mamtellrilleq south of the Kuskokwim River by the old Air Force

airport, and the island that once was in front of the present

site. They could explain why the original Yupiat did not settle

in the present site, the history of Kepenkuk (now Brown Slough)

and orutsaraq (place for gathering sphagnum moss for

caulking), the location of old reindeer corrals and so forth.

This would give our Yupiat a sense of kinship and belonging to

a place that one could call home and mean it, because it has

a well-documented story from the perspective of the Yupiat people.

I would encourage teachers to take their students

out into nature whenever possible, where the local language and

culture can come alive in natural ways. By doing this, you are

not limiting what is taught to knowledge alone, as the school

typically does, but paying attention to the deeper needs of the

student and the community. Within the classroom, the natural

rhythms of life can be tapped into through singing, dancing and

drumming, as well as other traditional activities that are acceptable

to Elders and parents. The essential balance that is represented

in the tetrahedral metaphor requires attention to all the realms

of life, including the human, natural and spiritual. This message

is blowing in the wind—a message older than our Native

ways.

References

Brailsford, Barry. Wisdom of the Four Winds. Stoneprint

Press: Christchurch, NZ, 1999.

Luke, Howard. Howard Luke: My Own Trail. Fairbanks:

Alaska Native Knowledge Network. 1999.

ANKN Website Update

by Asiqluq Sean Topkok

The Alaska Native Knowledge Network website has

grown quickly in the last few years. I was looking at the server

statistics from 1998 seeing that we received about 590,000 hits

in nine months. Currently, the ANKN website gets between 500,000

to 770,000 hits each month.

There are some very popular items on the ANKN website,

including:

| |

Marshall Cultural Atlas

http://ankn.uaf.edu/Marshall/

ANKN Cultural Standards

and Guidelines

http://ankn.uaf.edu/Standards/

Village Science

http://ankn.uaf.edu/VS/

Cultural Units

http://ankn.uaf.edu/Units/

Sharing Our Pathways Newsletters

http://ankn.uaf.edu/SOP/

Alaska Clipart Collection

http://ankn.uaf.edu/clipart.html |

All of the resources on the ANKN website are equally

helpful for educators, students and community members. We receive

many publications produced by ANKN (http://ankn.uaf.edu/publications/).

We also get some requests from individuals to name their dog

or do their homework: "Please send me all your materials

on Alaska Natives." There is a website by Alaska Native

Language Center just for dog names and I would feel more comfortable

having students do their own research for their assignments.

There is a search engine on virtually every page

of the ANKN web- site so finding resources should be easily accessible.

The ANKN directory, http://ankn.uaf.edu/directory.html, is

another way of finding what is on the ANKN website. Paula Elmes

and I are currently looking at how to better organize and present

the site, so if you have any comments or suggestions, feel free

to contact us anytime. We are directly accessible from the website

(fncst@uaf.edu).

Moving On . . .

by Masak Dixie Dayo

I

have accepted a position as an assistant professor with the Department

of Alaska Native and Rural Development and am excited about beginning

a new career as a faculty member. This change was a difficult

decision for me as I was so happy working at the Alaska Native

Knowledge Network as a program assistant and editor of Sharing

Our Pathways. Teaching rural development classes has long been

a goal of mine. The opportunity to teach about such subjects

as the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act and the concepts and

principles of healing was too much to resist. I

have accepted a position as an assistant professor with the Department

of Alaska Native and Rural Development and am excited about beginning

a new career as a faculty member. This change was a difficult

decision for me as I was so happy working at the Alaska Native

Knowledge Network as a program assistant and editor of Sharing

Our Pathways. Teaching rural development classes has long been

a goal of mine. The opportunity to teach about such subjects

as the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act and the concepts and

principles of healing was too much to resist.

As an RD assistant professor with duties of a student

recruiter and advocate for the RD program, I will also be able

to pay back the program that has given me so much both personally

and professionally. When the opportunity came, I tearfully wrote

my letter of resignation and literally cried when I spoke to

my co-workers about my decision. I haven't gone far though and

I think of my new position as an extension of our AKSRI work.

When I think about what prepared me for a rural

development faculty position, I fondly remember when my Aunt

Sally Hudson invited me to her Johnson O'Malley-sponsored skin

sewing and beading class. It was here that she taught us how

to bead, lectured about Alaska Native values and told us great

stories from her childhood in the traditional Athabascan way.

The class covered much more than tacking down beads on moose

hide—it fostered a keen interest in Athabascan culture

including food preservation, hunting, gathering, respect for

others and care of self in addition to boosting our adolescent

self-esteem.

Being an Iñupiaq of mixed blood I wasn't

very knowledgeable about my mother's Iñupiaq heritage

and therefore was a confused soul. Indian education and sewing

brought a new perspective to my life. I was taking correspondence

courses to complete high school as I hadn't adjusted very well

to the boarding home program and large city high school in Fairbanks.

I soon discovered when I worked hard and completed my course

work, I had more time to sew beads! Spending time with my two

moms, Elizabeth Fleagle and Judy Woods, enlightened me in new

ways—it added exciting new dimensions to our relationships.

When Western education was introduced to Alaska Natives, its

goal was to teach us the Western ways of living, thinking and

being. There was little or no thought that the skills and lifestyles

of Alaska Natives were equally rich in meaning and filled with

spirituality. Being an active participant in Alaska Native culture

gave my life new meaning and it began in an Indian education

class.

The rural development B.A. and M.A. programs remind

me of my Indian education experience. Rural development classes

are relevant to employment opportunities in rural Alaska and

our lives. RD graduates work for the regional and village corporations

and tribes as CEOs, presidents, vice presidents, land managers,

tribal administrators and in many other professional positions.

Rural development classes can be taken on campus or through the

applied field-based program. Elders lecture on such topics as

the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act and are hired as culture

bearers to share their traditional knowledge about subsistence

and many other areas. Seminars are the cornerstone of the applied

field-based program and provide opportunities for networking,

meeting faculty members face to face and learning place-based

education firsthand from local experts. Expanding one's worldview

with a traditional education and a global perspective is a powerful

combination for a well-rounded higher education. I describe the

rural development program as, "Place-based education with

a global perspective."

I applaud the hard work of the AKRSI and Alaska

Native Knowledge Network. It has been a wonderful six years working

at the ANKN office. Mentoring from the directors, staff, regional

coordinators and MOA partners definitely prepared me for my professional

and personal life challenges today and for the future. I look

forward to our continued working relationship. Please stay in

touch. I can be reached at 907-474-5293 or email dixie.dayo@uaf.edu.

ANSES State Fair Held at Camp Carlquist

by Greg Danner, Director of Programs & Exhibits,

The Imaginarium

The Alaska Native Science and Engineering Society

(ANSES) Statewide Native Science Fair was a success! The students

came, presented their projects and even managed to see some of

the Super Bowl. There was the unanimous sense that it was both

time and effort very well spent.

We had 8 sites, 37 students and 12 chaperones presenting

21 projects integrating science and local knowledge.

The winning project, by an eighth- and ninth-grade

pair from Circle (Yukon Flats School District) was entitled "Surviving

with Snow." The students explored the life-saving properties

of an emergency shelter constructed from snow. They even braved

a –54¡ day to gather data on the experiment. It was

the clear winner and both the traditional and Western science

judges gave it very high marks. They'll be going off to the national

AISES Fair in March.

Tyler Ely and John Carroll (Circle) with their first-place project.

|

Second-place winners Victoria Nathaniel and Ronald Mayo (Circle).

|

Third-place winners Ralph Christiansen and Ronnie Tunohun (third and

fourth from left) pose with Elder judges.

|

The Imaginarium in Anchorage provided logistical

support for the event under contract with the AKRSI and ear-marked

$1500 to support the winning project's trip to the AISES Fair

in New Mexico. The grand prize was awarded to the first place

winners at the fair and the chaperones from Circle will be accompanying

the students to the national fair. It was a very well received.

Congratulations go to all the winners and their teachers for

their prize-winning efforts.

Thanks to all the students, teachers, chaperones

and judges for their help in making the 2004 ANSES State Fair

a resounding success.

Southeast

Region: Southeast

Region:

S'áxt': Incorporating

Native Values in a Place-Based Lesson Plan

Vivian Martindale

In many Native American communities, plants have

medicinal, spiritual and cultural value. They aren't just some

green things that grow in the woods or in your front yard. According

to Tlingit oral traditions, Raven created man from a leaf. At

first Raven was going to create man from a rock, but then man

would have lived forever and that wouldn't have been right, so

by using a leaf man could move faster and also man would die.

This story illustrates the importance that plants have in the

lives of the Tlingit people.

One such plant, which is highly valued among the

Tlingit people, is found predominantly in the temperate rain

forests of Southeast Alaska. This plant is sacred to the Tlingit

people. The Tlingits call it s'áxt'; science

calls it Oplopanax horridum (Araliacea) and local residents call

it devil's club. The s'áxt' is also related to

the oriental ginseng and is sometimes called Alaska ginseng.

According to Alaska's Wilderness Medicines many different Native

peoples in Alaska use this plant for a variety of reason: cold,

flu, fever, stomach ailments, tuberculosis and poultices for

wounds such as black eyes and burns. Modern pharmaceutical, naturopathic

companies and other researchers are studying the plant for its

commercial medicinal values. Their studies reveal that s'áxt' may

possibly have hypoglycemic capabilities because the plant contains

a substance similar to insulin (Viereck 1987). Many Elders believe

that the plant will also prevent cancer or help in healing many

types of cancers.

In Southeast Alaska, among the Tlingit people,

the s'áxt' plant was used by shamans and contains

very powerful medicine and "when placed above doorways and

on fishing boats it is said to ward off evil"(U.S. Forest

Service). In the past, devil's club was associated with shamanism. "Shamans

may carry a power charm made with spruce twigs, devil's club

roots and their animal tongue, acquired during their quests.

During the quest (a novice who feels called to shamanism quests

for his power) a novice goes into the woods for one or several

weeks, eating nothing but devil's club" (Alaska Herbal Tea

2002).

Devils' club can be found in small or very large

patches throughout the woods or beach areas. The plant likes

wet, but filtered soil. S'áxt' grows up to eight

feet tall and the large maple-like leaves and stalks of the plant

are stems are covered with stickers, similar to slivers of glass

or wood that can easily get under the skin or through light clothing.

Stickers from the plant can cause infection and pain if not removed

immediately. The plant also contains blooms of berries in the

summer. "These berries are not edible by humans but bears

do eat them" (U.S. Forest Service). According to local harvesters "The

roots and shoots of devil's club are edible," however, the

stage for harvesting the plant is in the spring when the stalks

first sprout new green growth. This is the best time to harvest

the roots and new shoots, which can be ground into a powder and

made into tea. Some Elder sources say that in late summer or

fall you can harvest the bark from the stalks and the root-stalks.

It is best to consult the local Elders rather than rely on conventional

scientific documents or public agencies. Despite this, the U.S.

Forest Service advises, "The leaf spines, though visible,

are soft and pliable at this stage. Once they stiffen, however,

the shoots should NOT be eaten." The leaf clusters may be

nibbled raw, or added to omelets, casseroles and soups like a

spice. "One or two is enough to add a unique tang to a common

meal" (U.S. Forest Service)."

Hence the reason I have chosen the subject of s'áxt' is

so I may illustrate how educators can create a lesson plan that

will enable the introduction of one or more of the Tlingit values,

as outlined by Elder Dr. Walter Soboleff, into the curriculum.

The Native values, according to region, can be found on the University

of Alaska Fairbanks' Alaska Native Knowledge Network website

located at www.ankn.uaf.edu. Dr. Soboleff lists these values:

As well, this lesson explores the concept of "naturalist

intelligence" as outlined by Howard Gardner. By enhancing

the student's naturalist intelligence a curriculum such as this

guides the students to the understanding of how their Native

values work in everyday life. The naturalist intelligence "refers

to the ability to recognize and classify plants, minerals and

animals including rocks and grass and all variety of flora and

fauna" (Checkley: 9). Author and educator Karen Roth examines

this intelligence in her booklet The Naturalist Intelligence:

An Introduction to Gardner's Eighth Intelligence. Implementing

the eighth intelligence into the classroom setting is accomplished

by introducing students to the practicality of the natural world—one

that they can relate to their own lives in their own regions.

Many local Elders are rich with this intelligence, able to identify,

classify and relate the plants to the spiritual and cultural

workings of the Native communities. By utilizing this naturalist

intelligence, Elders and educators can introduce the Native values

into the classroom and community.

Roth introduces educators to the various ways with

which a classroom could implement this intelligence. In one method,

Roth outlines a model based on four stages. This model, designed

by David Lazear, is used to awaken the naturalists' intelligence. ".

. . he suggests the naturalist intelligence be triggered by immersing

the student in the natural world of plants, animals, water, forests,

etc., using the five senses" (Roth 1998). First, there is

the "Awakening" stage, which is accomplished through

immersion. The second stage is called "Amplify" and

in this stage the intelligence is strengthened through practice,

such as learning about where the plant grows and why. The third

stage, "Teach," is "using specific tools of this

intelligence and applying them to help learn"; it is the

stage when your objectives are achieved (17). "Transfer" is

the fourth stage. This is when students apply the naturalist

intelligence beyond the classroom. In other words, students will

be thinking about how to view their Native values beyond what

they have learned about the s'áxt'.

Through the study of the abundant and highly recognizable

local plant, students will be able to recognize how the Tlingit

values play out in their everyday lives. In A Yupiaq Worldview:

A Pathway to Ecology and Spirit, Dr. Angayuqaq Oscar Kawagley

points out how important it is for students to acquire knowledge

from the experiences in the world around them. Kawagley contrasts

this relation to the whole with the Western classroom that may

pose an "impediment to learning, to the extent that it focuses

on compartments of knowledge without regard to how the compartments

relate to one another or to the surrounding universe" (1996:87–88).

It is knowing about the plants in our environment, such as s'áxt',

and how to use that knowledge in our environment that makes the

knowledge we seek worthwhile. Therefore students, searching for

knowledge in their natural environment, will flourish and be

able to apply new concepts to their familiar place.

To begin, the introduction of Native values need

not be difficult. I suggest a dialogue to open up the discussion

about the values and how they are transmitted from one generation

to another. Students will be able to see the difference between

rigid book learning and field-based or place-based learning models.

Then introducing a teaching unit that will tie in one or more

of those values will get the students to thinking about how those

values are transmitted through daily life. In the article "The

Domestication of the Ivory Tower: Institution Adaptation to Cultural

Distance", Barnhardt illustrates how the field-base environment

is prime for learning. The field-based program outlined by Barnhardt

is "a reality-based, collective learning process " (4).

In a field-based program Barnhardt points out the benefit to

both teachers and students when the students are required to

participate in experiences. The experiential learning environment

is not detached, but thrives in the interactions between people

and their experiences. This place-based or field-based environment

is key to relating the Native values to the curriculum and to

the outside world.

S'áxt': Incorporating Native

Values in a Place-based Lesson Plan

Grade Level

Middle school, high school and possibly college

level

Utilizing placed-based education to introduce

the Tlingit values (see list of values above)

Math, science, art, writing, language and cross

cultural studies

-

Working with Elders:

-

Elders explain the cultural significance

of s'áxt': spiritually, medicinally, etc.

(value: reverence, care of human body, responsibility,

dignity).

-

Elders can show students the best places,

times and type of plants to harvest (value: care of subsistence

areas, peace with the world of nature).

-

Elders can talk about the methods of harvesting

and assist with this in the classroom and outside the classroom

(value: remember Native traditions, responsibility).

-

Proper identification of s'áxt',

its habitat, uses and preparations.

-

Introduction to Tlingit terms for the parts

of the plant and words and phrases associated with the activities.

-

The role of s'áxt' in art: beads

and/or rattle and then translate to ceremony (value: dignity,

remember traditions).

ACTIVITIES AND METHODS: HARVESTING & PREPARATION

-

Harvesting the s'áxt'

-

Have Elders or other local plant experts

assist with appropriate harvesting tools, what types of

plants to look for, appropriate clothing such as gloves

for protection, thick pants and coats (value: care for

human body).

-

Roots: Dig up long, straight pieces that

are 1/2" thick or larger.

-

Make sure there is a time for thanking the

plant for its gift (value: care, respect, reverence, truth).

-

Explore methods of preparation:

-

Salve or ointments: One method is to shave

the bark off the stalks and boil with canola oil, strain

it, mixed it with beeswax. Afterwards this mixture is poured

into empty medicine containers for use as a salve (value:

care of human body, sharing).

-

S'áxt' tea: The roots and

greenish inner bark can be shredded and dried or fresh

steeped into tea (value: humility, peace).

-

Roots:

-

Students can peel, roast and then mash

the roots.

-

Wash the roots as soon as possible with

a plastic bristle vegetable scrubber. Then peel off

the root bark with a knife and place on screens to

dry (value: sharing, respect, peace).

-

Making Beads, Jewelry or Deer Hoof Rattles:

-

Pauline Duncan's instructions for Deer

Hoof Rattles can be found on the ANKN website (value:

remember, reverence).

-

Beads: Beads are made from dry stalks

of s'‡xt'. They are cut from the stalk, hollowed

out and then dried. They can be painted or left natural.

The twine for stringing the beads is usually made from

mountain goat (value: sharing, humility).

-

-

Local plant experts: Elders, U.S. Forest Service,

local medicinal healers, herbalists

-

Pauline Duncan's Tlingit Curriculum Resources:

Picking Berries can be located at http://ankn.uaf.edu/Tlingit/PaulineDuncan/Books/Berry/devilclub.html

-

Alaska's Wilderness Medicines: Healthy Plants

from the Far North by Eleanor Viereck

-

A good kitchen and work space for making salves,

beads, etc.

-

Harvesting tools: knives, small shovel, cooking

implements, beeswax, oils

-

Other books illustrating what the plant looks

like, paper and pencils for on-site illustrations

Evaluation

Evaluation methods should be culturally and community

relevant. Students can keep a journal or write about what values

they observed in action. As well, students should be able to

produce salve, brew tea, know the basics of harvesting and prep

procedures and also to be able to make a piece of jewelry or

art from the plant. Afterwards students should be able to relate

what they have done, at every step of the way, to one or more

of the Tlingit values.

In conclusion, educators and Elders should be constantly

considering where and how values can be incorporated into learning

activities. At first it might be necessary to point out where

the values might fit in, however, as the lesson and the relationships

with the Elders progress that will no longer be necessary. Prior

to undertaking the lessons, have the students be aware that they

are looking for those values. At the end of each day, excursion

or lesson, students can be asked what values they observed at

work and how they might pass on those values to others or apply

them in their daily lives, stressing that almost all the Tlingit

values can be applied in one way or another to any daily living

situation.

Raven knew what he was doing, creating man from

a leaf. By using the simplicity of a leaf, Raven connected us

to our environment forever weaving Native values into our creation

thus into our lives.

Editor's note: Reference list is

available upon request.

Southeast

Region: SEANEA Update Southeast

Region: SEANEA Update

by Andy Hope

The Southeast Alaska Native Educators Association

elected a new board of directors and officers in January. Here

is the list of officers and board members for 2004:

Officers

Ted Wright, Chair

I was born and raised in Sitka where I graduated

from high school in '74, and then went to college for several

years in-between some years of work. I graduated from Southern

Oregon State with a degree in education/English and another in

educational administration from Penn State. I worked for the

Sitka Tribe and then moved over to Mt. Edgecumbe High School

as an English teacher and basketball coach. I worked for the

Commissioner of Health and Social Services as a special assistant

and then returned to Penn State to finish a Ph.D. in education

theory and policy. Somewhere in there I got married, had a son,

got divorced, had two dogs, saw some of the world, managed the

Sitka Tribe, worked several years as a consultant in Juneau,

Sitka and other places, taught at Southern Oregon University,

ran the Sealaska Heritage Foundation, spent a year in Anchorage

at UAA, did some other stuff, came back to Sitka and Juneau to

develop a tribal college and now I am working on a regional Native

charter school. I'm Eagle/Kaagwaantaan. My Grandmother is Jennie

Wright (98 years young and still having a good old time at the

Sitka Pioneer Home). There will be a test later. Happy trails.

Roxanne Houston, Vice-Chair

My name is Roxanne Houston and I am Tlingit and

Iñupiaq. My Tlingit name is Wooshdei.dioo and I belong

to the Kaagwaantaan Clan. I am the daughter of Roscoe and Vivian

Max Jr. and granddaughter of Joseph and Elizabeth Paddock and

Roscoe and Harriet Max, Sr. My husband, Dennis, and I will celebrate

twenty years of marriage in the fall and between us we have five

children: Joshua, Katrina, Jeremiah, Dennis, Jr. and Jacob. I

received my Bachelors of Education in elementary education from

the University of Alaska Southeast, in August of 1995. I applied

and received a Hawkins Fellowship to attend the Pennsylvania

State University in January of 1996. In December of 1996, I received

my Masters of Education in educational administration. I am currently

employed as a tribal recruitment coordinator for the Southeast

Alaska Regional Health Consortium. I serve as a council member

for the Sitka Tribe of Alaska. I am honored and look forward

to serving on the Southeast Alaska Native Educator's Association

board. Gunalcheesh!

Rhonda Hickok, Secretary

I was born in Anchorage, Alaska and grew up mostly

in Glennallen and Valdez. My mother is from Holy Cross and my

father was from Beaver. I am Athabascan, Iñupiat and Aleut.

I am married and have three children: two boys in high school

and a daughter in the third grade. My higher education began

at UAA and I eventually earned my Bachelors of Education through

the University of Alaska Southeast. Currently I am finishing

up a Masters of Arts in cross-cultural studies through the University

of Alaska Fairbanks. At present, I work for the University of

Alaska Southeast, Center for Teacher Education as the director

of the PITAS program. Prior to that I worked as a junior high

teacher for the Copper River School District (going back home

was fun!) and as a secondary social studies teacher for the Juneau

School District. I also worked as the Indian Studies and Title

VII ESL/LEP director for the Juneau School District. During my

time at the Juneau School District I was a teacher in the Early

Scholars Program, which is a joint program between the University

of Alaska Southeast and the Juneau School District that aims

at increasing the participation of Alaska Native students in

higher education. I miss the classroom environment and hope to

someday be back in the trenches of education.

Laurie Cropley, Treasurer

I am Tlingit, a daughter of Mabel Moy and Ike Cropley,

T'akdeintaan, Raven. I am an advisor/counselor at Sheldon Jackson

for Native students in Sitka employed under SJC's Title III grant.

I graduated from this infamous but historic 125-year-old college

with a degree in human services. I currently produce KCAW-FM's "Indigenous

Radio", serve on the associated alumni board of Sheldon

Jackson, serve as secretary of Sitka ANB Camp #1 and serve on

the presidential search committee for the Sheldon Jackson College

president. (Please forward candidates names from Alaska for this

permanent position.)

Board Members At Large:

Ronald E. Dick PhD

My father is A-ni Tsalagi (Cherokee Western Band)

and my mother is German. When we moved to Sitka, we enrolled

the girls (Collauna and Chohla) in the Sitka Native Education

Program where they grew up Tlingit. Vicki Bartels adopted me

into the Eagle Moeity, Chookaneidi Clan. I have a B.A. in psychology

and a Ph.D. in forest resources. I have been a college professor

for over 25 years and I have been active in Southeast Alaska

Native education for 19 years. My highest priority now is to

help develop the Southeast Alaska Tribal College.

Mary Jean Duncan

I was born in Juneau and raised in Yakutat by Maggie

Harry, my very wise, old grandmother whose Tlingit name was Neechx

yaa nas.at of the Kwasshkakwaan Clan. I am from the Raven Clan

and my moiety is (chaas) Humpy. My house is the half moon house

(Dis Hit). I grew up in a Tlingit-speaking environment which

I had to leave at the age of six. I could understand Tlingit

as a little child, but it wasn't long before my first language

was forgotten in a new English-speaking environment. My grandmother

taught me that it is very important in our Tlingit tradition

to know one's name, moiety, clan and protocol. She taught me

that this is the way things are, this is the way it must be and

gave me an understanding of what was right and wrong, of identity

and place that has stayed with me like a seed that would grow

when I was ready to find it. I am currently teaching fifth grade

and the head teacher at Angoon Elementary. I have been teaching

elementary for thirteen years. As an educator, what I find most

satisfying in the classroom is that moment when my students comprehend

a concept (the "Ah ha!" moment). In my teaching practice,

I strive to find ways to "hook" my students, spark

their natural curiosity and keep them interested in learning

more. I am familiar with the Macintosh computers that my school

is currently using. I integrate technology into my curriculum

by using computer programs to rehearse word processing, create

multimedia projects and student-directed research on the Internet.

Students gain valuable computing skills through the integration

of technology. I look forward to the many new techniques I can

learn and bring home to students at Angoon Elementary and my

colleagues at both the elementary, middle and high school.

Andy Hope

My Tlingit name is Xaastanch. I am a member of

the Sik'nax.ádi clan of Shtax'héen Kwáan,

X'aan Hít (Red Clay House). My father's clan is Kiks.ádi

X'aaká Hít (Point House) of Sheet'ka Kwáan.

I was born and raised in Sitka and have lived in Juneau since

1988. I graduated from Juneau-Douglas High School in 1968 and

received a Bachelors of Education from the University of Alaska

Fairbanks in 1979. I am currently working on a Masters of Arts

in cross-cultural studies. I have served as Southeast regional

coordinator for the Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative since December,

1995 and took on the Teacher Leadership Development coordinator

position in September, 2003. I have served as chair of the Southeast

Alaska Tribal College board of trustees since 1999.

Rhoda Jensen

My name is Rhoda Jensen from Yakutat, Alaska. My

Tlingit name is Naat'see and I am Kaagwaantaan Wolf. I am the

child of Iñupiaq Roscoe H. Max, Jr. of Pelican, Alaska.

I am the grandchild of Lukaax.adi Joseph H. Paddock. I am very

proud of being born and raised in Pelican, Alaska which is a

community that my grandfather helped build (he was a piledriver)

in the late 1930s. In 1991, I married Jonathan Jensen of Yakutat

and we are the proud parents of Jocelyn, Cody and Jonathan, Jr.

I have worked for the Yakutat Tlingit Tribe since 1999 as the

JOM/education director and recently took over the tribal environmental

planner position. I consider myself a strong advocate for education

for all our Native peoples. I also consider myself a Tlingit

language advocate and have continually looked for funding to

rekindle our language for our children's future. I currently

am the ANB/ANS Camp #13 secretary and hold a seat on the Yakutat

Indian Education committee. I look forward to serving on the

Southeast Native Educator's Association board (SEANEA). Gunalcheesh!

Marie M. Olson

I was born in Juneau, Alaska. I attended elementary

BIA schools in Juneau and Douglas and Alaska High School at Wrangell,

Alaska. I graduated from Garfield High School in Seattle, Washington.

I have been married and divorced, with one daughter and three

sons (one deceased, 2003). I attended Berkeley University in

1970 and 1971 on a Ford full scholarship and earned a BLA degree

from UAS, cum laude. I have also completed 200 plus credits of

continuing education courses. I have worked for Pacific Telephone

Company in San Francisco and Communications Workers of America

(executive board member of Local 9410, SF, CA). I managed overall

operation of Alaska Native Arts and Crafts in Juneau, served

as executive director of Southeast Community Action Program,

Southeast Elder for AKRSI, board member of AKABE/BMEEC and volunteer

for HeadStart/Auke Bay Elementary School. I teach a graduate

class on Cultural and Intellectual Property Rights for UAF; author

a Tlingit Coloring Book and own Card Shark Cultural Consultant.

Southeast

Region: A Native Charter School in Juneau Southeast

Region: A Native Charter School in Juneau

by Ted Wright

The Sealaska Heritage Institute and the Southeast

Alaska Native Educators Association are in the midst of planning

for development of a Native charter school in Juneau. A charter

school operates as a school in the local school district except

that the charter school is exempt from the local school district's

textbook, program, curriculum and scheduling requirements. The

principal of the charter school is selected by an academic policy

committee and can select, appoint or otherwise supervise employees

of the charter school. In addition, the school operates under

an annual program budget as set out in the charter contract between

the local school board and the charter school.

We are discussing the creation of a Native charter

school at an interesting time. Late winter events in Juneau include

a petition drive to re-examine the issue of funding and building

a second high school in the valley and new incidences of racism

remind us that old attitudes and beliefs die hard as too many

Native students continue to feel alienated and even unsafe in

their own schools. But even before these events were unfolding,

we were considering the possibility of a Native charter school.

In the final analysis, at least three factors are critical to

our decision to undertake this work:

-

Native students continue to score far below

their white peers on grade-level tests of academic proficiency

in reading, writing and math, and on tests of general achievement.

-

As they consider their relative academic standing

and struggle to fit-in at a school where they may feel alienated,

many Native students simply leave the system.

A few find their way to alternatives like GED programs

and correspondence study, but many do not and so they fall through

the cracks. The language, culture and place-based curriculum

of a Native charter school will inspire many students to learn

and to succeed. Further, higher numbers of Native teachers employing

a more traditional pedagogy and an underlying focus on Native

ways of knowing, will be attractive to Native and non-Native

students alike. And finally, regardless of whether we can verify

a causal link between the above factors and academic success,

the fact that there is substantially increased attention to the

particular needs of Native students will increase their likelihood

of success.

Native students, teachers, parents, community leaders

and other concerned citizens will have to want their own school;

attendance has to be at a high enough level to make it financially

feasible (150–200 students).

Sufficient human, financial and political resources

have to be directed at the creation of a Native charter school

in Juneau so that it sets a standard for how such schools can

be developed in our region and throughout the state. Moreover,

a full-range of commitment will demonstrate that we truly believe

that the education of our children is our highest priority and

that our actions speak louder than our words.

Plan for Development

At least two meetings a month will be scheduled

between the beginning of February and the end of April. Students,

parents, teachers, administrators, Native leaders and others

of the general public will be invited to participate. The agenda

will include most of the critical elements of charter school

development that will be required in a completed charter school

application, including at least the following:

-

Whether a school is needed/wanted

-

Grade levels & time frame for additions

-

-

Governance (bylaws/policies)

-

-

Administrator(s) and teachers

-

School calendar and daily rotation

-

-

-

-

-

Concurrent with the public meetings, a planning

team organized from those who attend will meet with representatives

of the Juneau School District, University of Alaska Southeast

and Department of Education and Early Development. These meetings

will ensure that the charter school is developed in accordance

with the wishes of the Native community, the requirements of

state law, the best practices known to the academy (university)

and the cooperation of local district educators and administrators.

In May the finished application will be presented

to the Juneau School District board, followed by a presentation

to the State Board of Education. Upon approval, serious fundraising

and organizational development will commence. It is anticipated

that the school will begin classes in the fall of 2005, though

the planning process may lead to adjustments along the way, including

when certain milestones are to be achieved.

For more information or to participate in the charter

school planning process, please contact Ted at (907) 523-2128

or send email to: tedtrmp@aol.com.

Unanga{* Region: The Education

of a Seal Hunter

*To accurately view the Unangam-Tunuu

fonts, you will need to install the font on your computer.

Available at www.alaskool.org.

by Moses Dirks

A

prime example of the way learning occurs in an out-of-school

setting is when Native people go about their subsistence activities.

The topic I will use to illustrate traditional learning is sea

lion hunting. A

prime example of the way learning occurs in an out-of-school

setting is when Native people go about their subsistence activities.

The topic I will use to illustrate traditional learning is sea

lion hunting.

Long ago, Unanga{ men were the main hunters of

sea mammals. The men would prepare to go hunting by cleansing

themselves before a hunt by sleeping separately from their wives,

because they did not want the sea lion to get jealous of the

hunter if s/he found out that he had slept with his wife the

night before. This also had to do with the woman's scent. If

the animal smelled a woman it would scare the animal away and

the man would not experience a successful hunt. The scent of

a woman was considered bad luck for hunters. When I was growing

up my sister or mother were not allowed to touch the firearms

used in hunting. The men believed that it caused the hunter to

come home empty-handed.

Long ago Unanga{ men hunted from an iqya{ (one-man)

skin-boat with only a harpoon. He would harpoon the animal and

the tip of the harpoon would enter the animal and detach inside

the animal without killing it. On the other end was an inflated

seal stomach, which served as a buoy. The hunter pursued the

animal until it got tired and then he would pull up alongside

and club it to death. Once the animal was dead, he and his partner

would tow it ashore and the butchering took place on the beach.

All parts of the animal were used. The sealskin was used for

clothing and covering the iqya{, and the stomach was

used for packing dried fish and meat. The intestines were used

in making gut skin raincoats, called chigda{, which

were durable and light enough so they did not hamper the paddler

from maneuvering his iqya{ in tricky waters. The whiskers

of the sea lion were used in decorating the hunter's hat, called chaxuda{,

The length and stoutness of the whiskers determined the status

of the hunter. All the meat was preserved by drying until the

Russians introduced rock salt, which was then used in storing

the meat for the long winter months.

All

of the traditional form of education occurred in the natural

world. The young hunters responsibility was to

observe and learn by watching and imitating the moves that were

produced in making the event happen. The young hunter was most

likely the nephew trained by the mother's brother. He would be

the apprentice hunter learning under the tutelage of his uncle.

Training at times was really harsh. Cold water bathing was one

of the tactics used, where the young man was told to take a bath

in the cold saltwater early in the mornings. They called it "toughening

the hunter up" so that he could endure the cold frigid waters

when hunting on the sea.

The training started at a very early age when the

young boys arm was stretched back while sitting down on the ground

as if sitting in the iqya{, so that he would grow up

naturally to throw the harpoon with velocity and distance. Other

kinds of training included hanging from the barabara roof rafters

to strengthen their arms in case they had to climb cliffs for

bird hunting or egg gathering. The exercises continued until

he could prove to his uncle that he was capable of being a successful

hunter. He would prove that by getting his first seal or sea

lion. Only then would he be considered a man in the Unangan hunting

and gathering society. Before the coming of the Russians, the

Unangan were a very self-sufficient and healthy people. Even

with their crude weapons they were excellent hunters.

Today hunting technology has changed so much that

by the time I was old enough to go hunting, all traditional technology

was gone. The wooden dory or homemade plywood skiffs replaced

the iqya{. Later came the fiberglass skiffs and aluminum

boats. High-powered rifles, more powerful and accurate, replaced

the harpoon. Bolas were replaced by shotguns for hunting birds.

Now we have to learn how all these machines work, because the

repair shop can be a thousand miles away.

There is usually someone in each village that knows

about fixing motors. My cousin, for instance, has never completed

high school but he is a master mechanic. He can fix outboards,

cars and trucks. How does he do this with no formal training?

His aptitude for fixing engines is very high, so he is depended

on to fix the machines. Now-a-days, owning and running a skiff

is expensive and if you don't have a job it is hard to get out

there for hunting, etc. You have to buy gas and oil for the motor,

paint and a trailer for your boat as well as a truck or an ATV

to haul it back and forth. Rifles and shotguns need to be kept

clean and oiled otherwise they don't function right. Rust is

the major culprit on guns. Along with the gun you need to buy

shells that are expensive from the local store. These days, hunting

is an expensive proposition.

I have taught Unangan culture for the last 15 years

and I still can't believe how different it is to teach in a classroom

setting. Whenever you want to bring a seal or sea lion into a

classroom you have to get permission from your principal, then

get approval from DEC to make sure it will be safe to handle

the blood pathogens and raw meat. In the past this was never

a problem, because most of the butchering was done out in the

field before the animal was brought into the village. As a result,

if you are trying to teach a unit on traditional activities in

a classroom, you often have to resort to textbooks and there

are very few texts that deal with the inner organs of a sea lion.

What little are available often do not clearly explain where

the organs of the animals are located and most of the texts come

in black and white so you can't even positively identify the

organs.

Elders don't like coming into the classrooms; they

were never allowed in the past, so they feel uncomfortable in

schools. It is so unnatural to be sitting in a classroom hour

after hour learning from a book. I once knew an Elder from one

of the villages who told me that he was getting sick because

he was not getting any exercise since he moved in from the village.

He sat around too much and he said that it was not healthy. He

would rather do hands-on type of work, so he always found things

to do around town. The Elder lived to be in his nineties.

Classroom settings are good for the Unanga{ for

the first hour. Listening to a person talk for more than an hour

is unheard of in my culture—the only time you would hear

talking amongst the Unanga{ would be when they were telling stories

at night. Unanga{ people are used to hands-on, kinesthetic type

of learning; learn by watching how it is done, trying it out

and if you don't master it the first time you do it again and

again until you know how to do it.

I

would sometimes be awestruck by what some of my relatives could

do—machinist, electrician, carpentry—you

name it, and they never went to school for these trades. If you

ask them, "How did you learn how to do that?" they

would credit God for giving them the skill so that they can do

what they need to do. As I venture down the road and think about

those intelligent people that I knew, I sometimes shudder to

think, what would have happened to them if they had gone to school?

Unanga{ Region: The Unangan Science Fair Unanga{ Region: The Unangan Science Fair

by Moses L. Dirks

Aang from the Unangan/s Aleut Region.

It is good to be back working with the AKRSI and TLDP group and

working on Native ways of knowing and indigenous science initiatives.

I am presently working with a local science teacher and whenever

I get the opportunity I am putting indigenous science into the

curriculum where it is appropriate. This is done so that Native

students can start thinking about what indigenous knowledge means,

what it is and to help them develop a science project they can

enter into the ANSES science fair.

I

am using ANKN resources available by Alan Dick* on

how to set up science fairs. It has been a valuable resource

in that it made students start thinking about the science that

is all around us in our villages and towns that can be applied

to everyday life.

The science teacher allowed me to present some

lessons from Village Science in his class. This was a good introduction

to what to look for in village science projects. After a few

lessons from Village Science, I contacted Alan Dick and asked

him if he had material on how to set up science fairs. He said

that he was working on one and was willing to share it with me.

A few days later I received a packet with the booklet and presented

that to my seventh-grade class. After presenting the material

the question was posed to the students: What do you think would

be a good village science project that you could enter in the

ANSES Science Fair? These were some of the ideas that we elicited

from our students:

In November we started research on our science

projects and finally, in January, the Unalaska City School District

sponsored a science fair so that winners could participate in

the statewide ANSES Fair held at Camp Carlquist January 30 to

February 2, 2004. The focus of the science fair was indigenous

sciences. With very little time left, we had our local science

fair and after the judges made their decisions, the following

winners were announced:

1st Place: Insulation: How the Unangan People

Used Natural Material to Insulate Their Semi-Subterranean

Huts Called an Ula

2nd

Place: Native Technology—Fox Trap

Klisa: How You Can Build a Fox Trap With All Natural Materials

and Make it Work

3rd Place: Plants and Their Uses: How the

Unangan Used Plants as Food and Medicine.

Our first place winner, Delores Gregory, went on

to state ANSES Fair and placed second in the seventh- and eighth-grade

category. We are very proud of Delores and hope to see her again

next year.

All the students that participated in the science

fair had fun and they all know what to expect for next year so

they will be better prepared for the event. Not only was it fun

for the students, they also learned about the knowledge of their

ancestors and how to use the scientific method to do their experiments.

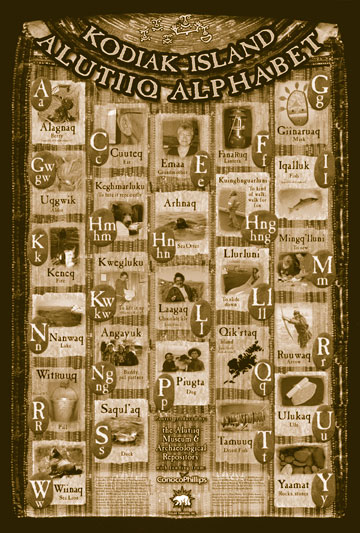

Alutiiq

Region: Alutiiq Museum Releases Language Poster & CD Alutiiq

Region: Alutiiq Museum Releases Language Poster & CD

by April Laktonen Counceller and Shauna Hegna

On February 4, 2004 the walls of the Alutiiq Museum

reverberated with the sounds of the Alutiiq language. The community

of Kodiak joined the museum in celebrating the premiere of the

Sharing Words project. This project, which includes an Alutiiq

alphabet poster, interactive CD-ROM and a loanable Alutiiq language

education box, was developed from the Alutiiq Word of the Week

(AWOTW) program.

The AWOTW consists of an Alutiiq word, a sentence

including that word and a cultural lesson. The AWOTW program

is very successful, but people always ask how to sound out the

words and sentences they see in print. Because of the level of

language loss in the Kodiak region, the average Alutiiq person

(also known as Sugpiaq) needs the most basic level of educational

language materials. "We wanted to publish a collection of

the AWOTW, but we needed to start with the alphabet," says

education coordinator April Laktonen Counceller.

The Alutiiq Museum, with guidance from the Qik'rtarmiut

Alutiit (Alutiiq People of the Island) Regional Language committee,

created an interactive CD-ROM that teaches the sounds of the

alphabet and includes the 260 audio recordings collected from

the AWOTW. Language masters Nick Alokli, Florence Pestrikoff

and Nadia Mullan provided the audio recordings, while local designer

Janelle Peterson engineered the computer lesson. In addition

to the alphabet and grammar lessons, there is a foreword discussing

the language and its revitalization, as well as video clips of

Elder Phyllis Peterson singing traditional Alutiiq songs. The

Kodiak Alutiiq Dancers donated introductory music. Each CD-ROM

is paired with a copy of the Alutiiq Alphabet Poster—a

full-color poster featuring the 26 letters of the Koniag Alutiiq

dialect and culturally-relevant photographs illustrating each

example.

"The Alutiiq language education box, alphabet

poster and interactive CD-ROM marks the beginning of a great

movement in Kodiak," Shauna Hegna, Alutiiq language coordinator,

said, "We are creating tools that will help our people build

the next generation of fluent Alutiiq speakers."

The alphabet poster and CD-ROM set is being distributed

free to local and regional education institutions, museums, libraries

and tribal councils. If your organization is interested in utilizing

these language- learning materials and would like a free copy,

please contact LaToya Lukin, Alutiiq Museum receptionist at alutiiq2@ptialaska.net

or call (907) 486-7004. The CD-ROM is also accessible through

the Alutiiq Museum website at http://www.alutiiqmuseum.com. Individuals

can purchase the set at cost through the museum gift shop.

The

Alaska Native Knowledge Network announces: The

Alaska Native Knowledge Network announces:

Alaska Science Camps, Fairs & Experiments:

Available in mid-March. Meanwhile,

the full version is available in a PDF

download from our website.

Camps

Camps have emerged as successful means of sharing

information and experiences that are not possible in the regular

classroom setting. They provide young people with the opportunity

to interact with Elders and instructors in an environment that

naturally promotes learning.

The need has long been expressed, and is now

fulfilled, to have a science fair with projects based on locally-

and culturally-relevant events. This book details how to plan

and sponsor a culturally-relevant science fair.

There is no better place for science exploration

than villages as there are so many questions that have not

been asked or answered by scientists. Students learn how to

pick and develop an exciting project that is based on their

local culture.

For more information or to order contact ANKN at

907-474-1902.

NSF Rural Systemic Initiatives • Alaska

Rural Systemic Initiative • University of the Arctic

NSF Tribal Colleges and Universities Program• Consortium for Alaska

Native Higher Education

Invite you to join us for a celebration

of

Education

Indigenous to Place

A week-long series of

events for the intrepid educator

May 15–19, 2004

Hess Conference Center • Pike's

Waterfront Lodge • University of Alaska Fairbanks |

Thursday and Friday, May 13–14:

Consortium for Alaska Native Higher Education Annual Meeting

Saturday, May 15, Day 1: Indigenous

Higher Education Colloquium

The first day will provide an opportunity for

representatives from indigenous-serving higher education institutions

and the Governing Council for the University of the Arctic

to address issues of common concern (e.g. joint programs, distance

education, collaborative research, accreditation, etc.) to

be followed with the development of an action plan that will

be reviewed for adoption during the Part II session on Wednesday,

May 19.

Sunday, May 16, Day 2: Indigenous

Curriculum Fair

Day 2 will focus on issues around developing

culturally-responsive curriculum materials and teaching strategies,

with participants invited to bring examples of culturally responsive

curriculum resources to be put on display and shared. Displays

will be in the form of posters, interspersed with presentations

around curriculum themes.

Monday, May 17, Day 3: Rural Systemic

Initiatives PI/PD Meeting

Day 3 will be the first of a two-day national

RSI PI/PD meeting addressing issues specific to the Rural Systemic Initiatives.

Tuesday, May 18, Day 4: RSI PI/PD

Meeting

Day 4 will be the second of a two-day PI/PD meeting

addressing issues specific to the Rural Systemic Initiatives.

May 19–23: International

Congress of Arctic Social Sciences

The remainder of the week will consist of workshops

and symposia associated with the tri-annual International Congress

of Arctic Social Sciences, including the symposium listed below.

Further details are available at http://www.uaf.edu/anthro/iassa/icass5sessab.htm.

Symposium on "Integrating

Indigenous Knowledge, Ways of Knowing and World Views into

the Educational Systems in the Arctic"

Abstract: The symposium will provide participants

with examples of work that is currently underway in the circumpolar

region to assist schools and universities in integrating indigenous

knowledge, ways of knowing and world views into all aspects

of education, with a particular emphasis on using the local

cultural and physical environment as a laboratory for learning.

Presentations from each participating country/initiative will

include a description of the epistemological basis for the

initiative, the organizational structure being utilized, the

role of Elders, and the cultural documentation process involved,

as well as the implications of indigenous-based education for

curriculum development, teaching practices and support structures

for schools serving indigenous peoples

Alaska RSI Contacts

Co-Directors

Ray Barnhardt

University of Alaska Fairbanks

ANKN/ARSI

PO Box 756730

Fairbanks, AK 99775-6730

(907) 474-1902 phone

(907) 474-5208 fax

email: ray@ankn.uaf.edu

Oscar Kawagley

University of Alaska Fairbanks

ANKN/ARSI

PO Box 756730

Fairbanks, AK 99775-6730

(907) 474-5403 phone

(907) 474-5208 fax

email: oscar@ankn.uaf.edu

Frank W. Hill

Alaska Federation of Natives

1577 C Street, Suite 300

Anchorage, AK 99501

(907) 263-9876 phone

(907) 263-9869 fax

email: frank@ankn.uaf.edu |

Regional Coordinators

Alutiiq/Unanga{ Region

Olga Pestrikoff, Moses Dirks &

Teri Schneider

Kodiak Island Borough School District

722 Mill Bay Road

Kodiak, Alaska 99615

907-486-9276

E-mail: tschneider@kodiak.k12.ak.us

Athabascan Region

pending at Tanana Chiefs Conference

Iñupiaq Region

Katie Bourdon

Eskimo Heritage Program Director

Kawerak, Inc.

PO Box 948

Nome, AK 99762

(907) 443-4386

(907) 443-4452 fax

ehp.pd@kawerak.org

Southeast Region

Andy Hope

8128 Pinewood Drive

Juneau, Alaska 99801

907-790-4406

E-mail: andy@ankn.uaf.edu

Yup’ik Region

John Angaiak

AVCP

PO Box 219

Bethel, AK 99559

E-mail: john_angaiak@avcp.org

907-543 7423

907-543-2776 fax |

Lead Teachers

Southeast

Angela Lunda

lundag@gci.net

Alutiiq/Unanga{

Teri Schneider/Olga Pestrikoff/Moses Dirks

tschneider@kodiak.k12.ak.us

Yup'ik/Cup'ik

Esther Ilutsik

fneai@uaf.edu

Iñupiaq

Bernadette Yaayuk Alvanna-Stimpfle

yalvanna@netscape.net

Interior/Athabascan

Linda Green

linda@ankn.uaf.edu |

is a publication of the Alaska Rural Systemic

Initiative, funded by the National Science Foundation Division

of Educational Systemic Reform in agreement with the Alaska

Federation of Natives and the University of Alaska.

This material is based upon work supported

by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0086194.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations

expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and

do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science

Foundation.

We welcome your comments and suggestions and encourage

you to submit them to:

The Alaska Native Knowledge Network

Old University Park School, Room 158

University of Alaska Fairbanks

P.O. Box 756730

Fairbanks, AK 99775-6730

(907) 474-1902 phone

(907) 474-1957 fax

Newsletter

Editor

Layout & Design: Paula

Elmes

Up

to the contents Up

to the contents

|

The

University of Alaska Fairbanks is an Affirmative

Action/Equal Opportunity employer, educational

institution, and provider is a part of the University of Alaska

system. Learn more about UA's notice of nondiscrimination. The

University of Alaska Fairbanks is an Affirmative

Action/Equal Opportunity employer, educational

institution, and provider is a part of the University of Alaska

system. Learn more about UA's notice of nondiscrimination.

Alaska Native Knowledge

Network

University of Alaska Fairbanks

PO Box 756730

Fairbanks AK 99775-6730

Phone (907) 474.1902

Fax (907) 474.1957 |

Questions or comments?

Contact ANKN |

|

Last

modified

August 16, 2006

|

|

|