CONCEPTS TO BE TAUGHT:

NEW WORDS TO BE LEARNED:

- cede

- plague

- aboriginal

- assimilation

- reservation

- The General Allotment Act

- The Removal Act

CONSTRUCTING A CLOZE EXERCISE.

Select a passage that measures between 250-275 words. Type the first sentence intact. Type the rest of the material, double-spaced, leaving every 5th word blank. Make the blanks each approximately 15 spaces in length. Leave 50 blanks. Type the final sentence intact.

ADMINISTERING THE CLOZE EXERCISE.

Inform students that the purpose of the exercise is to gauge the difficulty of the reading matter. Show how the test works by putting a short passage on the blackboard. Emphasize that the clues are in the context, and that the words are often words such as a, an, the...etc.

Allow ample time for all to finish.

SCORING AND RECORDING,

Count the number of correct words. If synonyms are to be counted, a list of acceptable ones should be prepared in advance. Counting synonyms seldom makes any difference in the scores.

Multiply the number of correct responses by 2 to get the per cent. Record the results by writing the students' names in the appropriate column.

|

Below 40%

|

Between 40-60%

|

Above 60%

|

|

Trouble. Frustration Level. |

Functioning. Instructional Level. |

Easy. Independent Level. |

The cloze is considered to be a gross indicator of readability of printed material.

When I was very young, a Sunday-school teacher told us that the beauty of Joseph's coat was its many colors. I'm not sure I 1________ the teacher's thought then, 2________ I have since remembered 3 ________ many times.

One such 4 ________ was Christmas morning, 5 1943. ________ was serving in the 6 Pacific aboard the aircraft 7 ________ USS Monterey. The Monterey 8________ participating in a strike 9________ the heavily defended harbor 10________ Kavieng, which guarded the 11________ approaches to the Bismarck 12________. For many of us, 13 ________ was our first major 14________ action. I remember thinking 15________ myself: here we are, 16________ 1500 men together in 17________ ship from all walks of 18________ and from every conceivable

19________ and national heritage, and 20________ united in one objective--- 21________ for our country. To 22 ________, the experience was----and 23________ ---symbolic of America's greatest 24________ : unity out of diversity.

25________ rest of the world 26________ sees only our diversity. 27________ we Americans understand the 28________ of our indivisible Union. 29________ the bond serves us 30________ peace as well as 31________ war.

God and man 32________ America what it is---33________ America has also made 34________ us what we are. 35________ most nations of history, 36________ are a mixture of 37________ multitude of races, nationalities, 38________ and cultures. Who can 39________ us as Americans simply 40________ how we look, how 41________ act, how we worship, 42________ by our names? Yet 43________ know who we are, 44________ have been saying ever 45________ Daniel Webster, and probably 46________ , "Thank God I am 47________ American."

We have so 48________ to be thankful for 49________ have

fuller freedom for 50________ and greater opportunities for self-fulfillment

than have ever existed elsewhere. Because of the way in which our forebears

shaped a free, diverse society in the bountiful New World, Americans in our

first 200 years as a nation have overcome the full spectrum of

adversity--winning independence, taming the wilderness, surmounting the ravages

of cruel civil war.

CLOZE READING EXERCISE ON AMERICAN INDIANS AND THE LAND

When the whites arrived, there was no square mile unoccupied or unused. Land was important to 1________ Indian people. Being of 2________ it was often a 3________ of war between Indian 4________. Land was used exclusively 5________ a particular band or 6________. It was not available 7________ other Indian groups for 8________ or settlement. Land belonging 9________ bands or tribes had 10________ identified boundaries which were 11________ to all people in 12________ area. These boundaries were 13________ so well defined that 14________ were later used by 15________ U.S. government to 16________ ceded to 17________ by the Indians. Trespassing 18________ another tribe's property was 19________ invitation to war.

Most 20________ the land was not 21________ by individual people. Rather, 22________ ownership of the 23________ was shared by all 24________ of the group. Parts 25________ the land might be 26________ for farming or fishing 27________ by families. These were 28________

a small part of 29________ larger area controlled by 30________ band or tribe.

The 31________ which later became known 32________ the United States were 33________ by bands or tribes 34________ Indians. They had exclusive 35________ and ownership of the 36________ and could transfer it 37________ others. It is this 38________ organized 39________ groups which is the 40________ or Indian 41________. But Indians did not 42________ the pieces of paper 43________ proved their ownership. They 44________ no deeds and titles. To 45________ white colonists used 46________ transactions, the Indians 47________ not own the land. 48________ did usually agree that 49________ Indians used the lands. 50________ that basis the colonists were able to justify purchasing the land from the tribes occupying it.

1. the |

17. it |

33. owned |

| 1. understand 2. but 3. it 4. occasion 5. I 6. South 7. carrier 8. was 9. against 10. of 11. northeastern 12. Sea 13. this 14. combat 15. to 16. some |

17. one 18. life 19. race 20. we're 21. fighting 22. me 23. remains 24. strength 25. The 26. often 27. But 28. mystery 29. And 30. in 31. in 32. made |

33. but 34. of 35. Unlike 36. we 37. a 38. religions 39. identify 40. by 41. we 42. or 43. we 44. and 45. since 46. before 47. an 48. much 49. We 50. self-government |

Using the words in sentences. Good idea to use names of class members in the sentences.

As students read, ask them to make a list of words they do not know (either meaning or pronunciation).

Working in small groups, have them look up meanings and pronunciations and write them on pieces of newsprint or butcher paper.

Post the word lists prominently around the room.

Hold frequent class drills on the words.

Have students make up word games, using the words.

Probably nothing contributes as much to reading improvement as does vocabulary training. It works for both horizontal improvement, learning more about words already known, and for vertical improvement, learning new unknown words. Vocabulary should be taught both as part of and separate from the reading period.

|

Two lists: |

Word |

Appropriate Meaning |

DESIRED STUDENT OUTCOME:

Students will become familiar with words related to the study at hand.

STRATEGIES:

Either list words on the board or prepare a set of bingo cards for each student.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Write all the definitions on a set of cards.

Draw definitions from a pot and have students either write words down from the board or fill in bingo cards.

USING SQ3R TO GET THE MOST FROM YOUR READING

ANDSTUDY OF THIS CHAPTER

SURVEY: Glance quickly at the material. Look at the:

- Pictures

- Title

- First Sentence

- Last Paragraph

- Key Words

QUESTION:

As you survey, ask yourself questions. What do the pictures tell you? Are they funny? Will the material be funny too? Are the men in first picture the same ones mentioned in the title? What are they doing? What else could they be doing? Does the first sentence answer that question? You'll think of more questions. The steps so far have taken about half a minute, but every second is time well spent.

READ:

Now read the material. You will find answers to your questions. You will begin to get the author's ideas. You will also remember facts that you already know, and you will think of new questions. It will be something like talking back and forth with the author. Does what he says make sense? Is he answering your questions?

REVIEW:

Think about all of the material. If you need a clearer grasp of certain facts, skim through the material again. You will often need to review.

RECITE:

When you recite, you show what you have learned. Sometimes, when you are reading a book, you will review and recite silently to yourself.

USING SQ3R WITH TEXT BOOKS

In dealing with textbooks or other reading materials (except fiction), SQ3R becomes a vital tool.

SURVEY:

Locate the exact page of the assignment. Estimate how long it will take you and how much time you are going to spend on it now.

Study the title; state it as a question; think what the words mean.

Glance through the assignment, looking briefly at

Read the chapter summary (or the last paragraph if there is no summary).

Read any questions at the end of the chapter.

QUESTION:

In surveying your textbook, questions may not stand out readily. One way to obtain these valuable helpers is to turn heads or subheads into questions. Example: "The Years Preceding War" might become For how many years did the war build up? "Outbreak of Hostilities" might become What caused actual fighting to begin? Once you start asking questions, more will come to mind. You'll find your interest in your assigned work growing with each question. You may want to jot some of them down to be answered later through your reading. Remember: Every second you spend in the survey and question steps is very worthwhile. Surveying will make your reading easier, and you will understand it better.

READ:

Be a flexible reader; adjust your speed to your needs. If a word meaning is not clear to you through its use in the selection, reread. If it is still unclear, underline the word or jot it down and look it up when you finish reading. Especially in reading magazines and newspapers, ask yourself: What is the writer's purpose? What is he trying to get me to think giving facts or opinions?

REVIEW:

It is well to review each section just after reading it. Close your book and see how much you can recall. Go back over important details you failed to recall. When you have finished reading the whole assignment, leaf through the chapter, recalling the main ideas under each section heading. Think how these go together to form the main idea of the chapter.

RECITE:

The reciting step gives you an opportunity to demonstrate your learning - to yourself, to your teacher. You may recite by answering questions in class, by writing a composition about the lesson, by outlining it, by reporting on it, or by taking a test on it. In any event, you may want to write brief notes after reading each section or completing the entire assignment. Notes can greatly help you retain what you have learned.

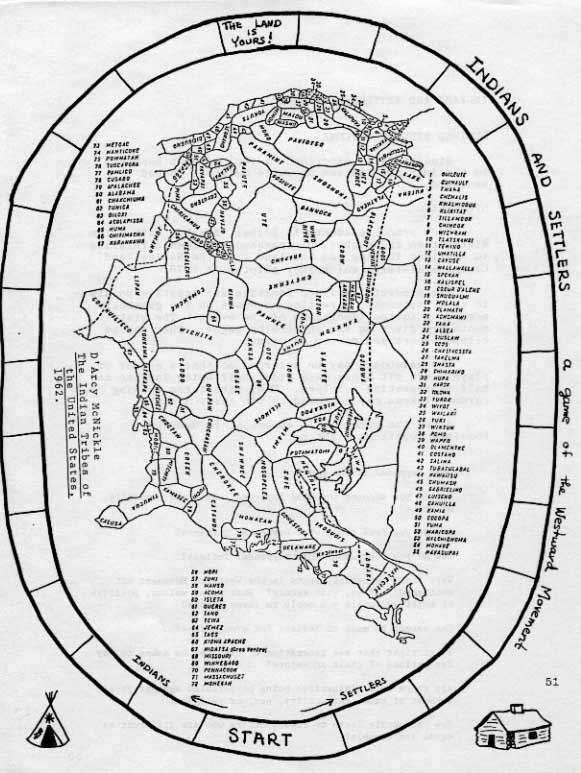

THE INDIAN TRIBES OF THE UNITED STATES

D'Arcy McNickle, The Indian Tribes of the United States,1962

Using your American History book as reference, show where major groups of Europeans settled after 1492:

Color each area a different color.

Which Indian tribes were displaced by each group of Europeans?

Where did each go?

DESIRED STUDENT OUTCOME:

Students will participate in an exercise illustrating historical bias.

STRATEGIES:

Have each student individually, without discussion, write 2 paragraphs describing the 2 most important events that happened at school yesterday.

Read the paragraphs aloud.

How many people selected the same events as "most important"? If not, why not?

Do all historians agree upon what were the most important events?

If American history had been told by Indians, what differences would there have been? By women?

If the class had discussed yesterday's events in advance, would there have been more consensus as to what events were important?

What is meant by the statement that, "History is an agreed-upon myth"?

DESIRED STUDENT OUTCOME:

Students will experience a feel of what happened to the American Indians as white settlers pushed westward.

STRATEGIES:

High school students in Bethel, Alaska, with Allen Wintersteen as teacher, paraphrased statements relating to American Indians and the land from the Native Land Claims mini-texts which they piloted in 1976.

The students assigned positive and negative points to each statement, directing movement on the gameboard according to the importance of the event. The statements are given on the succeeding pages. They may be clipped apart and pasted on cards.

The gameboard may be enlarged so that a number of players can sit along each side, half being Indians and half representing settlers. They take turns drawing cards. Tokens may be moved as the cards dictate.

After the game, it is essential to debrief. Possible questions might be:

INDIANS AND SETTLERS

|

THE U.S. ARMY IS WINNING THE WESTERN INDIAN WARS. Settlers move ahead 2 spaces. |

INDIANS CAN'T LEAVE THE RESERVATION WITHOUT PERMISSION. Indians move back 2 spaces. |

|

THE U.S. GOVERNMENT TAKES THE LAND EVEN IF THERE IS NO SIGNED TREATY. Indians move back 2 spaces. |

ALMOST ALL THE BUFFALO HAVE BEEN KILLED OFF FOR THEIR TONGUES AND HIDES. Settlers move ahead 2 spaces. |

|

EACH INDIAN FAMILY CAN MEET ITS OWN NEEDS. Indians move ahead 1 space. |

INDIANS HAD FEW CHOICES. Indians move back 1 space. |

|

THE U.S. GOVERNMENT HELPS WHEN THE STATES FAIL TO HELP THE INDIANS. Indians move ahead 1 space. |

THE PLAINS INDIANS ARE PROBABLY THE FINEST LIGHT CAVALRY IN THE WORLD. Settlers move back 2 spaces. |

|

WHITES HAD FALSE IDEAS ABOUT THE INDIANS SO THIS ALLOWED THEM TO TAKE THEIR LAND. Indians move back 2 spaces. |

THE INDIANS WERE THOUGHT OF AS SAVAGES--NO HOME, NO LAW, NO GOVERNMENT. Indians move back 3 spaces. |

|

THE INDIANS WERE THE GREATEST DOMESTICATORS OF FOOD AND FIBER PLANTS. Indians move ahead 3 spaces. |

THE CHEROKEES LOVE THEIR GEORGIA LANDS; NINE STATES REFUSE TO HELP INDIANS. Indians move back 2 spaces |

|

THE INDIAN ALLOTMENT ACT IS PASSED. HALF OF ALL INDIAN LANDS ARE TAKEN BY THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT. Settlers move ahead 4 spaces. |

GENERAL COOK GOT SOME LESSER CHIEFS TO SIGN A TREATY EVEN THOUGH MOST OF THE TRIBE WAS AGAINST SIGNING. Settlers move ahead 3 spaces. |

|

INDIANS HAD TO CUT THEIR HAIR TO LOOK MORE LIKE WHITES. Indians move back 3 spaces. |

THE INDIANS ARE ON THE WARPATH. Settlers move back 1 space. |

|

THE INDIANS USED EVERY SQUARE MILE OF THE LAND. Indians move ahead 2 spaces. |

GUNS RULED THE LAND: THE WHITES HAD THE GUNS. Indians move back 4 spaces. |

|

THE INDIAN REMOVAL ACT BECOMES A LAW IN 1830. INDIANS ARE MADE TO MOVE WEST OF THE MISSISSIPPI. Indians move back 3 spaces. |

THE INDIAN ALLOTMENT ACT IS PASSED. HALF OF ALL INDIAN LANDS ARE TAKEN BY THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT. Settlers move ahead 2 spaces. |

|

WITH THE INDIAN ALLOTMENT ACT, INDIVIDUAL INDIANS GET OWNERSHIP OF TRIBAL LANDS. Indians move back 5 spaces. |

THE INDIANS FOUGHT BACK WHEN THEY SAW THEIR LANDS TAKEN AND GAME RUN OFF. Indians move ahead 4 spaces. |

|

SOME INDIAN AGENTS TRIED TO HELP THE INDIANS. Indians move ahead 1 space. |

INDIANS WERE FORCED TO MOVE TO A RESERVATION OR BE KILLED. Indians move back 1 space. |

|

THE SETTLERS DON'T UNDERSTAND INDIAN WAYS, DON'T FEEL IT'S WRONG TO TAKE INDIAN LANDS, CONTINUE TO TAKE IT. Settlers move ahead 3 spaces. |

EACH OF THE MANY INDIAN TRIBES CONTROL FROM 500 TO 20,000 SQUARE MILES OF LAND. Settlers move back 2 spaces. |

|

THE U.S. GOVERNMENT SAW INDIAN TRIBES AS INDEPENDENT NATIONS. Indians move forward 1 space. |

INDIANS ARE TOLD TO EAT SHEEP INSTEAD OF BUFFALO. Indians move back 1 space. |

|

INDIAN TRIBES ARE FORCED INTO LAND BELONGING TO OTHER TRIBES. CONFLICT RESULTS. Indians move back 3 spaces. |

INDIANS WERE FORCED TO DEPEND ON THE U.S. GOVERNMENT FOR FOOD AND SHELTER. Indians move back 3 spaces. |

|

THE GOVERNMENT THREATENED INDIANS TO MAKE THEM SIGN TREATIES. Indians move back 3 spaces. |

RESERVATION LANDS WERE UNSUITED TO HUNTING OR FARMING. Indians move back 4 spaces. |

|

INDIANS COULD NOT VOTE BECAUSE THEY WERE NOT U.S. CITIZENS. Indians move back 1 space. |

CONGRESS PASSES THE INDIAN REMOVAL ACT OF 1830. Settlers move ahead 4 spaces. |

|

WHITES ARE UPSET ABOUT INDIANS ROAMING OFF THEIR RESERVATIONS. Indians move back 1 space. |

INDIANS ARE TREATED FOR THEIR DISEASES BY THE ARMY DOCTORS. Indians move ahead 2 spaces. |

|

THE BUFFALO WERE KILLED OFF. Indians move back 1 space. |

From your own knowledge, or from a history book, make up additional playing cards. |

THE

ANIMALS, VULGARLY CALLED INDIANS

-Hugh Henry Brackenridge

DESIRED STUDENT OUTCOME:

Students will gain historical point of view on racial discrimination.

STRATEGIES:

Read this account aloud or listen to the tape.

This is a personal account by an American colonist who was alive 200 years ago. It describes how some early settlers regarded Indians.

With the narrative enclosed, I subjoin some observations with regard to the animals, vulgarly called Indians. It is not my intention to write any labored essay; for at so great a distance from the city, and so long unaccustomed to write, I have scarcely resolution to put pen to paper. Having an opportunity to know something of the character of this race of men, from the deeds they penetrate daily round me, I think proper to say something on the subject. Indeed, several years ago, and before I left your city, I had thought different from some others with respect to the right of soil, and the propriety of forming treaties and making peace with them.

In the United States Magazine in the year 1777, I published a dissertation denying them to have a right in the soil. I perceive a writer in your very elegant and usful paper, has taken up the same subject, under the signature of "Caractacus," and unanswerably shown, that their claim to the extensive countries of America, is wild and inadmissible. I will take the liberty in this place, to pursue this subject a little.

On what is their claim founded?-Occupancy. A wild Indian with his skin painted red, and a feather through his nose, has set his foot on the broad continent of North and South America; a second wild Indian with his ears cut in ringlets, or his nose slit like a swine or a malefactor, also sets his foot on the same extensive tract of soil. Let the first Indian make a talk to his brother, and bid him take his foot off the continent, for he being first upon it, had occupied the whole, to kill buffaloes, and tall elks with long horns. This claim in the reasoning of some men would be just, and the second savage ought to depart in his canoe, and seek a continent where no prior occupant claimed the soil. Is this claim of occupancy of a very early date? When Noah's three sons, Shem, Ham, and Japhet, went out to the three quarters of the old world, Ham to Africa, Shem to Asia, Japhet to Europe, did each claim a quarter of the world for his residence? Suppose Ham to have spent his time fishing or gathering oysters in the Red Sea, never once stretching his leg in a long walk to see his vast dominions, from the mouth of the Nile, across the mountains of Ethiopia and the river Niger to the Cape of Good Hope, where the Hottentots, a cleanly people, now stay; or supposing him, like a Scots pedler, to have traveled over many thousand leagues of that country; would this give him a right to the soil? In the opinion of some men it would establish an exclusive right. Let a man in more modern times take a journey or voyage like Patrick Kennedy and others to the heads of the Mississippi or Missouri rivers, would he gain a right ever after to exclude all persons from drinking the waters of these streams? Might not a second Adam make a talk to them and say, is the whole of this water necessary to allay your thirst, and may I also drink of it?

The whole of this earth was given to man, and all descendants of Adam have a right to share it equally. There is no right of primogeniture in the laws of nature and of nations. There is reason that a tall man, such as the chaplain in the American army we call the High Priest, should have a large spot of ground to stretch himself upon; or that a man with a big belly, like a goodly alderman of London, should have a larger garden to produce beans and cabbage for his appetite, but that an agile, nimble runner, like an Indian called the Big Cat, at Fort Pitt, should have more than his neighbors, because he has traveled a great space, I can see no reason.

I have conversed with some persons and found their mistakes on this subject, to arise from a view of claims by individuals in a state of seciety, from holding a greater proportion of the soil than others; but this is according to the laws to which they have consented; an individual holding one acre, connot encroach on him who has a thousand, because he is bound by the law which secures property in this unequal manner. This is the municipal law of the state under which he lives. The member of a distant society is not excluded by the laws from a right to the soil. He claims under the general law of nature, which gives a right, equally to all, to so much of the soil as is necessary for subsistence. Should a German from the closely populated country of the Rhine, come into Pennsylvania, more thinly peopled, he would be justifiable in demanding a settlement, though his personal force would not be sufficient to effect it. It may be said that the cultivation or melioration of the earth, gives a property in it. No-if an individual has engrossed more than is necessary to produce grain for him to live upon, his useless gardens, fields and pleasure walks, may be seized upon by the person who, not finding convenient ground elsewhere, choose to till them for his support.

It is a usual way of destroying an opinion by pursuing it to its consequence. In the present case we may say, that if the visiting one acre of ground could give a right to it, the visiting of a million would give a right on the same principle; and thus a few surly ill natured men, might in the earlier ages have excluded half the human race from a settlement, or should any have fixed themselves on a territory, visited before they had set a foot on it, they must be considered as invaders of the right of others.

It is said that an individual, building a house or fabricating a machine has an exclusive right to it, and why not those who improve the earth? I would say, should man build houses on a greater part of the soil, than falls to his share, I would, in a state of nature, take away a proportion of the soil and the houses from him, but a machine or any work of art, does not lessen the means of subsistence to the human race, which an extensive occupation of the soil does.

Claims founded on the first discovery of soil are futile. When gold, jewels, manufactures, or any work of men's hands is lost, the finder is entitled to some reward, that is, he has some claims on the thing found, for a share of it.

When by industry or the exercise of genius, something unusual is invented in medicine or in other matters, the author doubtless has a claim to an exclusive profit by it, but who will say the soil is lost, or that any one can found a claim by discovering it. The earth with its woods and rivers still exist, and the only advantage I would allow to any individual for having cast his eye first on any particular part of it, is the privilege of making the first choice of situation. I would think the man a fool and unjust, who would exclude me from drinking the waters of the Mississippi river, because he had first seen it. He would be equally so who would exclude me from settling in the country west of the Ohio, because in chasing a buffalo he had been first over it.

The idea of an exclusive right to the soil in the natives had its origin in the policy of the first discoverers, the kings of Europe. Should they deny the right of the natives from their first treading on the continent, they would take away the right of discovery in themselves, by sailing on the coast. As the vestige of the moccasin in one case gave a right, so the cruise in the other was the foundation of a claim.

Those who under these kings, derived grants were led to countenance the idea, for otherwise why should kings grant or they hold extensive tracts of country. Men become enslaved to an opinion that has been long entertained. Hence it is that many wise and good men will talk of the right of savages to immense tracts of soil.

What use do these ring, streaked, spotted and speckled cattle make of the soil? Do they till it? Revelation said to man, "Thou shalt till the ground." This alone is human life. It is favorable to population, to science, to the information of a human mind in the worship of God. Warburton has well said, that before you can make an Indian a christian you must teach him agriculture and reduce him to a civilized life. To live by tilling is more human, by hunting is more bestiarum. I would as soon admit a right in the buffalo to grant lands, as in Killbuck, the Big Cat, the Big Dog, or any of the ragged wretches that are called chiefs and sachems. What would you think of going to a big lick or place where the beasts collect to lick saline nitrous earth and water, and addressing yourself to a great buffalo to grant you land? It is true he could not make the mark of the stone or the mountain reindeer, but he could set his cloven foot to the instrument like the great Ottomon, the father of the Turks, when he put his signature to an instrument, he put his large hand and spreading fingers in the ink and set his mark to the parchment. To see how far the folly of some would go, I had once a thought of supplicating some of the great elks or buffaloes that run through the woods, to make me a grant of a hundred thousand acres of land and prove he had brushed the weeds with his tail, and run fifty miles.

I wonder if Congress or the different States would recognize the claim? I am so far from thinking the Indians have a right to the soil, that not having made a better use of it for many hundred years, I conceive they have forfeited all pretence to claim, and ought to be driven from it.

With regard to forming treaties or making peace with this race, there are many ideas:

They have the shapes of men and may be of the human species, but certainly in their present state they approach nearer the character of Devils; take an Indian, is there any faith in him? Can you bind him by favors? Can you trust his word or confide in his promise? When he makes war upon you, when he takes you prisoner and has you in his power will he spare you? In this he departs from the law of nature, by which, according to baron Montesquieu and every other man who thinks on the subject, it is unjustifiable to take away the life of him who submits; the conqueror in doing otherwise becomes a murderer, who ought to be put to death. On this principle are not the whole Indian nations murderers?

Many of them may have not had an opportunity of putting prisoners to death, but the sentiment which they entertain leads them invariably to this when they have it in their power or judge it expedient; these principles constitute them murderers, and they ought to be prevented from carrying them into execution, as we would prevent a common homocide, who should be mad enough to conceive himself justifiable in killing men.

The tortures which they exercise on the bodies of their prisoners justify extermination. Gelo of Syria made war on the Carthaginians because they oftentimes burnt human victims, and made peace with them on conditions they would cease from this unnatural and cruel practice. If we could have any faith in the promises they make we could suffer them to live, provided they would only make war amongst themselves, and abandon their hiding or lurking on the pathways of our citizens, emigrating unarmed and defenceless inhabitants; and murdering men, women and children in a defenceless situation; and on their ceasing in the meantime to raise arms no more among the American Citizens.

OUR BEGINNINGS: AN INDIAN'S

VIEW

-Frank

Jones

DESIRED STUDENT OUTCOME:

Students will look at early American history from the Indian point of view.

STRATEGIES:

Read this speech aloud or listen to tape.

In Boston, when an Indian, Frank James, was chosen to be orator at a celebration of the 350th year after the landing of the Pilgrims, he was prepared to deliver this speech.

He was refused permission.

I speak to you as a Man - a Wampanoag Man. I am a proud man, proud of my ancestry, my accomplishments won by strict parental direction - ("You must succeed - your face is a different color in this small Cape Cod community.") I am a product of poverty and discrimination, from these two social and economic diseases. I, and my brothers and sisters have painfully overcome, and to an extent earned the respect of our community. We are Indians first - but we are termed "good citizens." Sometimes we are arrogant, but only because society has pressured us to be so.

It is with mixed emotions that I stand here to share my thoughts. This is a time of celebration for you - celebrating an anniversary of a beginning for the white man in America. A time of looking back - of reflection. It is with heavy heart that I look back upon what happened to my people.

Even before the Pilgrims landed here it was common practice for explorers to capture Indians, take them to Europe and sell them as slaves for 20 shillings apiece. The Pilgrims had hardly explored the shores of Cape Cod four days before they had robbed the graves of my ancestors, and stolen their corn, wheat and beans. Mourt's Relation describes a searching party of 16 men - he goes on to say that this party took as much of the Indian's winter provisions as they were able to carry.

Massasoit, the great Sachem of the Wampanoags, knew these facts, yet he and his people welcomed and befriended the settlers of the Plymouth Plantation. Perhaps he did this because his tribe had been depleted by an epidemic. Or his knowledge of the harsh oncoming winter was the reason for his peaceful acceptance of these acts. This action by Massasoit was probably our greatest mistake. We, the Wampanoags, welcomed you the white man with open arms, little knowing that it was the beginning of an end; that before 50 years were to pass, the Wampanoags would no longer be a tribe.

What happened in those short 50 years? What has happened in the last 300 years? History gives us facts and information - often contradictory. There were battles, there were atrocities, there were broken promises - and most of these centered around land ownership. Among ourselves we understood that there were boundaries - but never before had we had to deal with fences and stonewalls; with the white man's need to prove his worth by the amount of land that he owned. Only 10 years later, when the Puritans came, they treated the Wampanoag with even less kindness in converting the soul of the so-called savages. Although they were harsh to members of their own society, the Indian was pressed between stone slabs and hanged as quickly as any other "witch."

And so down through the years there is record after record of Indian lands being taken, and in token reservations set up for him upon which to live. The Indian, having been stripped of his power, could but only stand by and watch - while the white man took his land and used it for his personal gain. This the Indian couldn't understand, for to him, land was for survival, to farm, to hunt, to be enjoyed. It wasn't to be abused. We see incident after incident where the white sought to tame the savage and convert him to the Christian ways of life. The early settlers led the Indian to believe that if he didn't behave, they would dig up the ground and unleash the great epidemic again.

The white man used the Indians nautical skills and abilities. They let him be only a seaman - but never a captain. Time and time again, in the white man's society, we the Indians have been termed, "Low man on the Totem Pole".

Has the Wampanoag really disappeared? There is still an aura of mystery. We know there was an epidemic that took many Indian lives - some Wampanoags moved west and joined the Cherokees and Cheyenne. They were forced to move. Some even went north to Canada! Many Wampanoags put aside their Indian heritage and accepted the white man's ways for their own survival. There are some Wampanoags who do not wish it known they are Indian for social and economic reasons.

What happened to those Wampanoags who chose to remain and lived among the early settlers? What kind of existence did they lead as civilized people? True, living was not as complex as life is today - but they dealt with the confusion and the change. Honesty, trust, concern, pride, and politics wove themselves in and out of their daily living. Hence he was termed crafty, cunning, rapacious and dirty.

History wants us to believe that the Indian was a savage, illiterate uncivilized animal. A history that was written by an organized, disciplined people, to expose us as an unorganized and undisiciplined entity. Two distinctly different cultures met. One thought they must control life - the other believed life was to be enjoyed, because nature decreed it. Let us remember, the Indian is and was just as human as the white man. The Indian feels pain, gets hurt and becomes defensive, has dreams, bears tragedy and failure, suffers from loneliness, needs to cry as well as laugh. He too, is often misunderstood.

The white man in the presence of the Indian is still mystified by his uncanny ability to make him feel uncomfortable. This may be that the image that the white man created of the Indian - "his savageness" - has boomeranged and it isn't mystery, it is fear, fear of the Indian's temperament.

High on a hill, overlooking the famed Plymouth Rock stands the statue of our great sachem, Massasoit. Massasoit has stood there many years in silence. We the descendants of this great Sachem have been a silent people. The necessity of making a living in this materialistic society of the white man has caused us to be silent. Today, I and many of my people are choosing to face the truth. We are Indians.

Although time has drained our culture, and our language is almost extinct, we the Wampanoags still walk the lands of Massachusetts. We may be fragmented, we may be confused. Many years have passed since we have been a people together. Our lands were invaded. We fought as hard to keep our land as you the white did to take our land away from us. We were conquered, we became the American Prisoners of War in many cases, and wards of the United States Government, until only recently.

Our spirit refuses to die. Yesterday we walked the woodland paths and sandy trails. Today we must walk the macadem highways and roads. We are uniting. We're standing not in our wigwams but in your concrete tent. We stand tall and proud and before too many moons pass we'll right the wrongs we have allowed to happen to us.

We forfeited our country. Our lands have fallen into the hands of the aggressor. We have allowed the white man to keep us on our knees. What has happened cannot be changed, but today we work toward a more humane America, a more Indian America where man and nature once again are important, where the Indian values of honor, truth and brotherhood prevail.

You the white man are celebrating an anniversary. We the Wampanoags will help you celebrate in the concept of a beginning. It was the beginning of a new life for the Pilgrims. Now 350 years later it is a beginning of a new determination for the original American - the American Indian.

These are some factors involved concerning the Wampanoags and other Indians across this vast nation. We now have 350 years of experience living amongst the white man. We can now speak his language. We can now think as the white man thinks. We can now compete with him for the top jobs. We're being hard; we are now being listened to. The important point is that along with these necessities of everyday living, we still have the spirit, we still have a unique culture, we still have the will and most important of all, the determination, to remain as Indians. We are determined and our presence here this evening is living testimony that this is only a beginning of the American Indian, particularly the Wampanoag, to regain the position in this country that is rightfully ours.

- How does his view of the cultural contact differ from that of Mr. Brackenridge?

- How does the history of the Wampanoag Tribe differ from that of the Alaskan native groups?

- In what way are their histories similar?

THE FIRST AMERICANS IN TODAY'S WORLD

In a message to Congress on July 8, 1970, President Nixon said:

"The first Americans - the Indians - are the most deprived and most isolated minority group in the Nation. On virtually every scale of measurement - employment, income, education, health - the condition of the Indian people ranks at the bottom."

DESIRED STUDENT OUTCOME:

Students will examine statistics on American Indians in the light of President Nixon's statement.

-We, the First Americans, U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Census.

STRATEGIES:

Have students make picture, circle, line, or bar graphs to illustrate the figures given.

Have students work in groups to examine employment, income, education, and health and present their findings pictorially to the rest of the class.

|

On Census Day 1970, a total of 792,730 of us were counted. Our population totaled 523,591 in 1960. When the first complete count of us was made in 1890, we numbered 248,253. So our population has grown by 208 percent since then. When the first U.S. census was taken in 1790, no mention was made of us whatever, and the next two censuses included all persons except "Indians not taxed." Between 1830 and 1850, censuses contained no specific mention of us. Until 1930, except for 1910 when a special enumeration of Indians was made, data about us were gathered on an irregular basis. The 1960 and 1970 censuses were the only ones in which self-identification was the basis for enumerating the Indian Population. They are considered the most accurate totals ever obtained. --We, the First Americans, |

INDIAN POPULATION GROWTH: 1890............ 248,253 1900............ 237,196 1910............ 276,927 1920............ 244,437 1930............ 343,352 1940............ 345,252 1950............ 357,499 1960............ 523,591 1970............ 792,730

U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Census. |

Have students make visual displays of this information.

-We, the First Americans, U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Census.

INDIAN POPULATION BY STATES: 1970 AND 1960

|

UNITED STATES Alabama .............. |

1960 792,730 2,443 |

1970 523,591 1,276 |

INDIAN POPULATION, 1970 On a blank map of the United States, show this information. Rank the top 10 Indian states in the nation. How do the figures given on Alaska compare with current enrollment figures? |

We earn our living in just about as many different ways as other Americans. Many of us tend to live close to the land on reservations -farming, ranching, and working at arts and crafts. In recent years there have been accelerated programs to establish industrial plants and commercial business there.

But 55 percent of us 16 years old and over who are employed work in urban areas, competing in the job mainstream. About 70 percent of Indian men work in four broad occupational groups: craftsmen and foremen, operatives, laborers, and service workers. Nine percent were in the professional and technical ranks in 1970. This was double the proportion in 1960.

About 70 percent of our working women 16 years old and over were in clerical, operative, and service jobs and 11 percent worked at professional and technical occupations.

|

MAJOR OCCUPATIONAL GROUPS IN THE INDIAN POPULATION: 1970 |

|

Service workers, except private household.…… 31,448 Craftsmen, foremen, and kindred workers.…… 27,303 Laborers, except farm………………………… 16,318 Professional, technical, and kindred workers... 18,938 |

Unemployment among us is an enormous problem. Our unemployment rate in 1970 was nearly three times the national average.

Have students make visual displays of this information.

More of us are attending school and staying there longer than in previous years.

As previously mentioned, more than half of us between 3 and 34 years old were in school in 1970; 95 percent of our young between 7 and 13 were in the classrooms, and our college enrollment had more than doubled since 1960.

Nine out of 10 of our children attend public schools. The remainder attend private, mission, and Federal boarding or day schools.

In 1970, a third of our people 25 years old and over had completed high school; the proportion was considerably less than one-fifth in 1960. Median years of schooling for Indians was 9.8 in 1970, the same as for Blacks. The national median was 12.1 years, and 52.3 percent of the population as a whole had completed high school. More than 7 percent of us had 1 to 3 years of college training in 1970, compared to 4.0 percent in 1960. One-fourth of our males between 16 and 21 years old were school dropouts.

Indians living in Washington, D.C. ranked above the national average in both median number of school years completed and in the proportion of high school graduates. Our median years of schooling there was 12.6, and 66 percent of us were high school graduates in 1970.

In contrast, the median number of school years completed on the Navajo Reservation was 4.1, and only about 17 percent of persons 25 and over were high school graduates.

Indian families tend to be slightly larger than those of the population as a whole. Nearly one-fifth of them were headed by a female in 1970.

Nearly half of us-49.8 percent-lived-in homes we either owned or were buying on Census Day 1970. This compares with a rate of 63 percent for the U.S. population.

A typical Indian family, both in urban areas and on reservations, lives in quarters built in 1939 or earlier. About 72 percent of our households have complete plumbing-that is, hot and cold piped water, an indoor toilet, and a bath for the exclusive use of individual households. For the population as a whole the proportion is 92 percent.

-We, the First Americans

Overcrowding is a problem for us. Based on the census definition of "overcrowded" as "more than one person per room," more than a fourth of us live in overcrowded quarters. One person in 12 lives under similar circumstances in the total population.

About half our households had at least one automobile available to them in 1970, while more than a fifth had two or more. About four-fifths of the households in the population as a whole had at least one automobile available.

Our annual median family income-meaning half of our families earn more, half less-was $5,832 in 1969; for the population as a whole it was $9,590. Thus, for every $100 all American families earned, Indian families made about $61.

Those of us who live in the Northeast had the highest median family income-$7,437; it was lowest in the South at $5,624.

There were wide ranges in the amount of family income we earned during 1969. In 30 metropolitan areas where at least 2,500 of us lived in 1969, our median family income was as low as $3,389 (in Tucson, Arizona) and higher than $10,000 (in Detroit and Washington, D.C.)- Higher than the median income figure for all U.S. families.

Reservation Indians did not fare as well. Their median family income ranged from a high of $6,115 on the Laguna Reservation in New Mexico down to $2,500 on the Papago Reservation in Arizona.

As American citizens we pay local, State and Federal taxes on our income the same as other citizens except where a treaty, agreement or statute exempts us. Most tax exemptions granted to us apply on lands held in trust for us and to income from such land.

--We, the First Americans

DESIRED STUDENT OUTCOME:

Students will compare Indians with the rest of the American population.

| INDIANS | GENERAL POPULATION | ALASKA NATIVES | |

| MEDIAN FAMILY INCOME | $1,500 | $6,882 | |

| UNEMPLOYMENT RATE | 45% | 4.6% | |

| AVERAGE SCHOOLING FOR ADULTS | 5 years | 11.7 yrs. | |

| AVERAGE LIFE EXPECTANCY | 63.5 yrs. | 70.2 yrs. | |

| INFANT MORTALITY RATE (Per 1,000 live births) |

35.9 | 24.8 | |

| INCIDENCE OF TUBERCULOSIS (Per 100,000 population) |

184 | 26.6 | |

| AVERAGE SCHOOL DROP OUT RATE | 50% | 29% | |

| BIRTH RATE (Per 1,000 population) | 43.1 | 21.0 |

STRATEGIES:

INDIANS

Compare and contrast the lot of American Indians with that of the general U.S. population in each of the categories listed.

What conclusions can you draw?

What hypotheses would you use to explain the differences?

What facts can you offer to support your hypotheses?

What other kinds of comparisons might be significant?

These figures were quoted in a Time-Life publication c. 1970. Will any of the information have changed?

Can you account for the changes?ALASKA NATIVES

Fill in the blank column on Alaska Natives, if you can locate the information. (The Daily News article quoted by the Tundra Times, Dec. 19, 1969, will supply some of the information as it stood then. Alaska Natives and the Land, by the Federal Field Committee for Development Planning in Alaska, Oct., 1969, contains a wealth of information, but is difficult to use.)

How do the facts on Alaska Natives differ from those of Indians and the general population?

How do you account for the differences?

Will any of the facts have changed since 1969?

CHEROKEE MEMORIAL TO THE U.S. CONGRESS

DESIRED STUDENT OUTCOME:

Students will compare changing Indian views.

" IN TRUTH, OUR CAUSE IS YOUR OWN. IT IS THE CAUSE OF LIBERTY AND OF JUSTICE.

IT IS BASED UPON YOUR OWN PRINCIPLES, WHICH WE HAVE LEARNED FROM YOURSELVES. FOR WE HAVE GLORIED TO COUNT YOUR WASHINGTON AND YOUR JEFFERSON OUR GREAT TEACHERS. . . WE HAVE PRACTICED THEIR PRECEPTS WITH SUCCESS.

AND THE RESULT IS MANIFEST.

THE WILDERNESS OF FOREST HAS GIVEN PLACE TO COMFORTABLE DWELLINGS AND CULTIVATED FIELDS. MENTAL CULTURE, INDUSTRIAL HABITS, AND DOMESTIC ENJOYMENTS HAVE SUCCEEDED THE RUDENESS OF THE SAVAGE STATE.

WE HAVE LEARNED YOUR RELIGION ALSO. WE HAVE READ YOUR SACRED BOOKS. HUNDREDS OF OUR PEOPLE HAVE EMBRACED THEIR PRACTICED THE VIRTUES THEY TEACH, CHERISHED THE HOPES THEY AWAKEN. . .

WE SPEAK TO THE REPRESENTATIVES OF A CHRISTIAN COUNTRY: THE FRIENDS OF JUSTICE, THE PATRONS OF THE OPPRESSED.

AND OUR HOPES REVIVE, AND OUR PROSPECTS BRIGHTEN, AS WE INDULGE THE THOUGHT. ON YOUR SENTENCE OUR FATE IS SUSPENDED. . .

ON YOUR KINDNESS, ON YOUR HUMANITY, ON YOUR COMPASSIONS, ON YOUR BENEVOLENCE, WE REST OUR HOPES."

--Cherokee Memorial to the United States Congress--Dec. 29, 1835.

(Questions for Discussion):

To what American principles did the Cherokee leaders speak in 1835?

Were those the principles that had ruled the American treatment of Indians before that date? Afterwards?

Quote historic events to support your opinion.

Do you agree or disagree with the statements by the Cherokee leader?

DESIRED STUDENT OUTCOME:

Students will become aware of Native land claims settlements going on outside Alaska.

STRATEGIES:

SEMINOLES ACCEPT LAND DEALMembers of Seminole tribes gather at a meeting in West Hollywood, Fla., where they agreed to accept-S16 million from the Federal government in return for 32 million acres of land. The Indians claim the land was stolen from them by Gen. Andrew Jackson more than 100 years ago. (AP Wirephoto)

- Find out all you can about the Seminole Indians.

- How is their history different from that of the Alaska Natives?

- How is their history the same?

- How does the Seminole land settlement compare with that of the Alaska Natives?

DESIRED STUDENT OUTCOME:

Students will become familiar with major treaties regarding Native Americans and the land.

STRATEGIES:

Prepare a set of clues, or have a group of students do this during their research.

Keep clues together for each separate act or treaty.

The teacher or student leader selects one pack of clues and reads them one at a time to the class. Students at any time may guess the answer by standing to be recognized.

If they are wrong, they are out of the game.

If they are correct, they become the leader (reader of clues) for the next round.

The teacher should be alert for points to be clarified or any other teachable moments or take-offs for discussion.

Use reward freely.

OTHER POSSIBLE CLASSROOM ACTIVITIES:

- Read about Tlingit ridicule totems. Make or draw an original ridicule totem.

- Draw a political cartoon having to do with a topic concerning Alaska or Alaska Natives.

- Locate a song or story which illustrates satire. Read it to the class or tape it or tell about it.

- Write a poem or short speech demonstrating Indian regard for the land.

- Develop a simulation game or games involving:

- Indian removal

- treaties

- reservations

- social organization of Indians.

- Demonstrate map skills by drawing a map of the village, noting geographical landmarks, boundaries, fishing, trapping, and hunting sites used by families.

- DEMONSTRATE TO THE CLASS ONE SKILL FROM TRADITIONAL NATIVE CULTURE THAT YOU FEEL CONTRIBUTES TO SOCIETY IN GENERAL.