|

HOW WELL ARE INDIAN

CHILDREN EDUCATED?

Chapter Three

DIFFERENCES IN STUDENT

BACKGROUNDS

A great many statements have

been made and articles written describing the Indian student,

often drawing comparisons between him and white

pupils. Good or poor achievement has frequently been explained

on the basis of racial or cultural differences between the two

groups. Up to the time of this study, no service-wide survey

has collected the data needed to draw valid conclusions in regard

to:

1) the actual difference between the achievement of Indian students

and white children from rural areas,

2) cultural differences between the two groups, or

3) the relation between achievement and cultural differences.

It may be said therefore that the objective of this survey is

three-fold:

1) to measure the educational achievement of students in Indian

schools,

2) to gather data relative to the cultural backgrounds of the

Indian and non-urban white students in Indian, public and mission

schools,

and

3) to determine the relationships, if any, which exist between

these measures of cultural background and school achievement.

Practical limitations made it necessary to collect cultural data

on a relatively small number of topics, but those which were

selected for study were those which seemed likely to be most

important as

an aid to interpreting the test data and also as indication of

the other information which should ultimately be collected during

the following years of the study.

Cultural Backgrounds of the Students

Table III-1 describes the degree of Indian blood of the students

in the three grade levels in the different types of schools and

in the different geographic areas. All of the entries in this

table are in terms of percentages. It has been broken down into

many

categories, and therefore it must be remembered that some of

the entries represent only a very small number of cases.

Some generalizations which can be drawn from this table are:

1) Nearly all of the students in the Navajo, Pueblo and other Southwest

schools are full-blood Indians.

2) There is a larger percentage of mixed-blood students in the

non-reservation schools than in any of the other types of Federal

Indian schools.

3) The public schools and mission schools selected for comparison

have a fairly wide range of students, extending from the full-blood

Indians to all-white students.

4) In view of the fact that the some criteria were used in the

selection of the fourth, eighth and twelfth grade public school

students, it is significant that there is considerable difference

in the percentage of non-Indians, i.e., white students at the three

grade levels, the fourth grade having 37% white students, the eighth

grade 51%, and the twelfth grade 70%. This would indicate that

there is a dropping out of Indian students in public schools in

the higher grades. Differences this great cannot be ascribed to

differences in total Indian population in these age brackets, for

the Bureau of the Census reports that 11.9% of the Indian population

falls in the age group 10-14 years, and 10.8% in the group from

15-19 years, as compared to percentages for native whites in the

same groups of 9.6% and 9.1%. The data therefore suggest the possibility

that the holding power of the public schools is greater for white

students than for Indian students.

In interpreting the tables and charts, it is necessary to keep

in mind that these data describe three separate groups of students

instead of the same students at three periods. Because of the large

number of older students who withdrew, both from Indian schools

and from public schools, during the war to enter the armed forces

and war work, all interpretations relative to differences between

students at the various grade levels are extremely tentative.

The data do not justify a conclusion that school success is limited

by the degree of Indian blood. It is true that relatively low achievement

is found in some of the areas where the percentage of full-blood

students is relatively high. On the other hand, in Oklahoma, where

65% of the fourth grade Indian School students are full-bloods,

the achievement is considerably higher on the various tests than

in Dakota, where there are fewer full-blood Indian students.

Another observation which can be made from this table indicating

the degree of Indian blood of the various students, is the tendency

for the higher grade levels to have a lower percentage of full-blood

Indian students than the lower grade levels. This would indicate

that the dropout has probably been higher among full-blood Indian

students.

The relation between the tendency to stay in school and the background

of the students can also be observed in Table III-2, which describes

the education of the parents of the students tested.

This table indicates a greater number of years of school attendance

by the parents of students in the upper grades. In other words,

students coming from homes in which the parents have had the advantage

of considerable

education, tend to remain in school longer than those coming from

homes where the parents have had little or no schooling. This is

even more significant

when one realizes that the parents of students eligible for the twelfth grade

normally belong to an older and less literate generation than do the parents

of the students eligible for the fourth or eighth grades. The report

of the Bureau of the Census

indicates that the Indian literacy has increased from 44% for

all Indians over 20 years of age in 1910, to 74.8% for all Indians

over 25 years of age in 1940.

For the mission and public schools, there is little or no difference

between the educational attainment of the fathers and mothers of

the children at the various grade levels, whereas in the Indian

schools the difference is quite noticeable. The number of years

of school attendance of the parents of the public school children

is, on the whole, higher than that of any of the other parent groups.

The educational level of the Indian parents in the Navajo area

is considerably below the level of parents in any of the other

regions, and it is also in this area that the students' achievement

is considerably below that of other areas.

In those areas in which pupils in public schools show superior

performance to the pupils in Federal Indian Schools, it will be

found that the educational attainment of the fathers and mothers

of those public school students is considerably higher than that

of the parents of the students in Indian schools located in the

same area. In areas in which the Indian students did as well or

better, than the public school students, such as in the Great Lakes

or Oklahoma areas, there is relatively little difference between

the educational attainment of the parents of the two groups. Table

III-2 shows that the number of years of schooling for the parents

varies greatly in different regions.

Data were collected on the number of generations known to have

taken advantage of educational opportunities. The data collected

were based only upon that information which students were able

to furnish. These data seemed to show trends similar to those already

observed by studying the data relative to the number of years of

schooling of the parents. Since the data concerning the education

of the parents is probably more reliable than that which pertains

to the education of the grandparents, nothing significant would

have been added by including the statistics relative to the latter.

Table III-3 describes the language reportedly spoken in the homes

of the fourth, eighth and twelfth grade students, according to

the 1946 study. It should be noted that this represents the language

which the student reported as that which is actually, habitually

spoken in the home--not the homes in which one

or both parents can talk and understand enough English to converse

in that language

if necessary. There is evidence that many students who, because

they speak English around school and are thought of as English-speaking,

actually speak only Indian when they are at home. It is also

apparent that

many adult Indians who speak perfectly good English when necessary,

elect to converse in their Indian language at home. It will be

noted

that the students in day schools come from homes in which less

English is spoken than do the students in any of the other types

of Indian schools. As would be expected, the public school children

have by far the greatest amount of English spoken in their homes.

This is true for Indian students in public schools, as well as

for whites in public schools. A

much greater proportion of English is spoken in the homes of the

twelfth grade students in Indian schools, and the proportion for

the eighth grade

is greater than that for the fourth grade. The language spoken

in the home appears to be correlated with school achievement and

also with the number of years the student remains in school.

The factor of home stability was studied because it has often been

claimed that broken homes may contribute to poor pupil achievement.

Table III-4 describes the home stability of the students by indicating

the percentage living with their parents, with only their father,

with only their mother, with relatives, or with non-relatives.

These data do not appear to have a direct or easily interpretable

relationship with any of the achievement scores, or with home

factors studied, but they

will probably prove of value and interest in personnel and- adjustment

studies. For example, the percentage of students living with

both parents is much smaller among students in non-reservation

boarding schools than in any other type of school;* yet the achievement

among non-reservation students was relatively high. The number

of students living with

both parents on the Navajo and Pueblo reservations is higher than

is the case either in the Dakotas or in Oklahoma; yet the Navajo

and Pueblo achievement was, in most cases, low and that in the

Dakotas and

in Oklahoma high. The data do not indicate, of course, that the

broken home is never a factor in the poor achievement of an individual

student, but they do indicate that, whatever the adverse effects

of a broken home may have been among these students, they are concealed

by other factors more directly affecting achievement.

* Dependency because of a broken home is one criterion for admission

to a non-reservation boarding school.

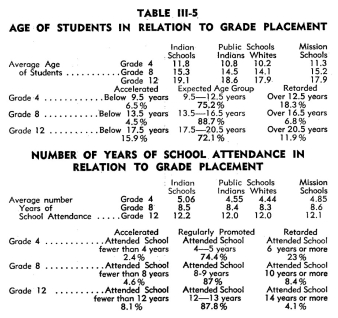

Table

III-5 shows the age distribution of the students in each of the

grades and types of schools studied, and the number of years

each of the students has attended school. One of the first observations

one makes from the table is that those students who are retarded

either from the standpoint of chronological age, or in the number

of years they have attended school, tend to drop out of school

before the completion of the eighth grade. At the fourth grade

level 23% of all the students have been in school six or more years.

Assuming no additional retardation, this group is comparable to

those of the eighth grade level who have attended ten years or

more, and at the twelfth grade level who hove attended fourteen

years

or more. Yet, at the eighth grade

level only 8% of the students, and of the twelfth grade level only

4% of the students, fall into this group. This decrease in the

percentage

of retarded students in upper grades could also be explained by

an acceleration during the interval or because more of the students

now entering have difficulties that result in early retardation.

Many students with low achievement have had it attributed to

the fact that circumstances have made it necessary for them to

transfer many times from one school to another.

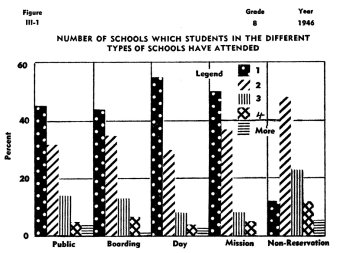

The information in Figure III-1 was collected on the eighth grade

students in 1945. In the

non-reservation schools, where achievement has been found to be

relatively high, most of the students have attended more than one

school. There appears to be no direct relationship between poor

achievement and frequent transfers from one school to another.

Relationships Between Measures of Cultural Background and School

Achievement

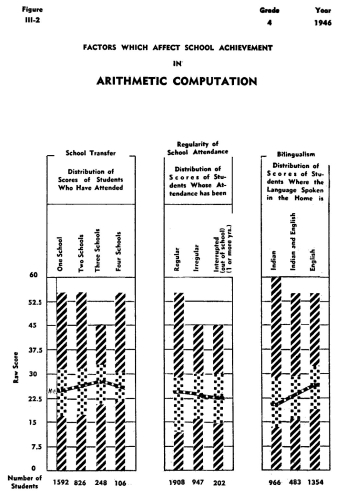

Figures Ill-2, 3, 4, and 5 summarize o segment of the cultural

background information collected, showing not only a wide variation

between the backgrounds of the students, but also a relationship

between several of these factors and school achievement.

The first four columns in Figures III-2 and 3 show the relationship

between the number of schools the student has attended and achievement

in arithmetic computation. In the case of the fourth grade, pictured

in Figure III-2, the achievement of the students in arithmetic

computation is lowest for students who have attended only one school.

While the differences are not large, the fact that achievement

is higher for students who have transferred gives some assurance

that the transferred student is not handicapped in his arithmetic

computation achievement by the number of times he has transferred.

It may be, of course, that students who transfer have certain other

qualifications which, in turn, are understandably related to success

in school. This may be a case in which the transfer itself is not

the cause of high achievement, but is only indicative of the fact

that a highly select group of students is forced to transfer. Some

might wish to read into this the added possibility that increased

effort on the part of both the pupil and the teacher results from

school transfer, thus resulting in higher achievement.

The relation of school transfer to twelfth grade achievement in

arithmetic computation is shown in Figure III-3, and to Part D

of the Gates Basic Reading test in Figure III-4. At the twelfth

grade level a larger percentage of students have experienced transfer,

but this is to be expected because by the time students have reached

the twelfth grade, most will have been forced to transfer of least

once or twice. The differences between the achievement of students

who have attended one school only, and that of students who have

attended several schools, is so small that it may have occurred

by chance. This fact bears out the observation concerning the analysis

in relation to achievement in arithmetic computation at the fourth

grade level, namely that there is little or no evidence that transfer

is a serious handicap to achievement in school.

Columns 5, 6 and 7 of Figure III-2 compare the regularity of attendance

of fourth grade students with achievement in arithmetic. As one

would expect, the higher achievement is made by students with

regular attendance and, with the exception of those who have been

out of school more than one year, the median achievement is lower

for those whose attendance has been irregular. It would appear

that the maturation of students who have been out of school one

or more

years tends to offset low achievement in arithmetic. At the fourth

grade level, the number of students who have been out of school

more than one year is so small as to make this sample less reliable

than for

the other groups studied. Referring to Figures III-3, and III-4,

it will be noted that the differences in achievement in arithmetic

computation, for students who have had different patterns of

regularity of school attendance,

are smaller than is true for their achievement on the Gates Basic

Reading Test, Type D. This would seem to indicate that a student's

out-of-school experiences ore less likely to compensate for his

lock of instruction in reading than in arithmetic computation.

The seemingly significant and more understandable differences are

those between the students who have attended school regularly and

those whose attendance has been irregular. The relatively high

achievement in arithmetic computation by upper grade students who

have been out of school more than one year might be explained through

the effect of training received in the armed forces, since a considerable

number of veterans were included in this group.

Figure III-5 shows the regularity of attendance for the eighth

and twelfth grade students and its relation to achievement on

the General Resources test. Here again, some of the same observations

can be made, and in the case of the twelfth grade pupils, it

would appear that somewhat irregular attendance does not seem

to hamper the students' achievement, and may even be associated

with whatever factors provide a beneficial effect. In most instances

the differences are not large, and may even have occurred by

chance, particularly in the cases where there are few students

in the group. In a subject such as General Resources, where regularity

of school attendance does not appear to contribute to high achievement,

it might be interpreted that the material represented by the

test was not actually being taught in the school.

Figures III-2, 3, 4, and 5, also show the relationship between

the language spoken in the home and school achievement in arithmetic,

General Resources, and Gates Basic Reading, Part D. Quite consistently,

students coming from homes where only English is spoken showed

higher achievement than those students coming from homes where

only Indian is spoken. Moreover there is seemingly little or no

difference between the achievement of those students from homes

in which only Indian is spoken and those in which both Indian and

English are spoken. It will be interesting to many to observe from

these figures that the fact that a student comes from a home in

which only Indian is spoken apparently does not place a ceiling

on his achievement, because there is a significantly large number

of students coming from homes where only Indian is spoken who do

better, even in the Reading test, than the average student coming

from a home in which only English is spoken. Therefore, failure

to use English in the home is not so great a handicap but that

it may be counterbalanced by many other factors of equal or greater

significance. It should not be overlooked, however, that coming

from a home in which little or no English is spoken is undoubtedly

a handicap to the student who receives his training in o school

where the development of a meaningful English vocabulary is not

given special consideration.

The last two columns of Figures III-3 and III-4 show the relation

between the educational attainment of the mothers of the students

and the students' achievement in arithmetic computation and reading.

Distributions of scores according to school grades completed by

the students' fathers show a pattern almost identical with these

patterns. It is interesting that the central tendency for both

tests increases with an increase in school grade completed by the

parents. However, more than one-quarter of the students whose parents

had completed nine or more years in school made scores below the

median of the students whose parents had attended school less than

five years. It is possible for other factors to counterbalance

or conceal the influence of lack of educational attainment by the

parents. On the other hand, it would appear that the educational

attainment of the parents, or factors associated with it, has a

favorable influence upon the students' achievement in both the

arithmetic computation and the reading tests.

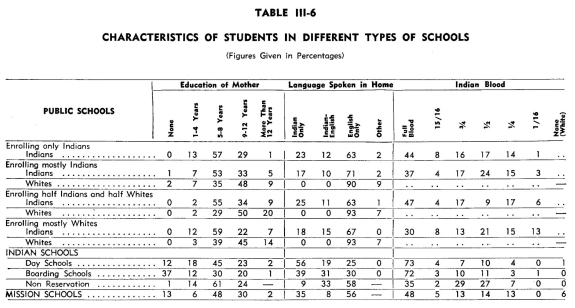

Indian Students in Public Schools

Table III-6 presents data which indicate that many of the Indian

children enrolled in public schools have a cultural background

more favorable to achievement in school than that of Indian children

enrolled in Federal Indian Schools. At the fourth grade level,

the parents of all Indian children in public schools had some formal

education whereas 37% of the mothers of students enrolled in Federal

boarding schools had never attended school. English is the only

language spoken in the homes of approximately 65% of the Indians

enrolled in public schools, as compared with 25% for students in

Indian day schools, 30% for Indian boarding schools, and 58% for

non-reservation boarding schools.

Because factors associated with white culture (the education of

the parents, the language spoken in the home, etc.) appear to affect

achievement favorably, one would predict that the achievement for

Indian students in public schools enrolling mostly white students

would be higher than that of Indian students in public schools

where few or no white students are enrolled. The opposite appears

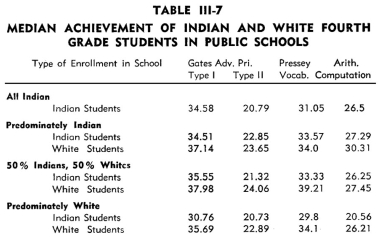

to be the case. Table III-7 shows the median achievement of Indian

and white, fourth grade, public school students in schools where

the enrollment is 1) 100% Indian, 2) predominately Indian, 3) 50%

Indian, and 4) predominately white. On three of the standardized

tests, the achievement of the Indian students in schools which

are predominately white is lower than that of Indians in any of

the public schools where fifty per cent or more of the students

are Indian. This unexpectedly poor achievement of Indians in predominately

white public schools may result from any one of o number of conditions.

It is possible, of course, that other factors, not measured in

this study offset the favorable effects of those factors which

have been named plus the apparently beneficial contact with white

students. It may be true that bilingualism is given less attention

in schools where the number of Indian students is small, and in

this case these students would demonstrate low achievement. Whatever

the contributing factors, there is no evidence that attendance

in o school where there are fewer Indian than white students, favorably

affects the school achievement of the Indian student.

Differences Between Interests of the Students

In addition to gathering data about the parents, home background,

and frequency of school attendance, information was sought relative

to the expressed interests of the students in the in-school and

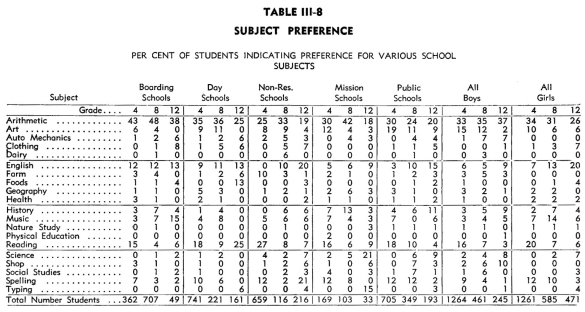

out-of-school activities. Table III-8 describes the degree to which

various school subjects were preferred by the students tested in

the 1946 study. The extremely high percentage of students indicating

strong preferences for such academic subjects as English, mathematics

and social science in 1945, raised the suspicion that perhaps the

free-response type of questionnaire then used had biased the responses

and caused the students to list as their first choices those

subjects which they

had either just been studying or those which they felt their teachers

might prefer them to mention. In an effort to correct this possible

bias, the 1946 study listed both academic and vocational subjects

alphabetically. The preference indicated by students at the fourth,

eighth and twelfth

grade levels reflected the same type of preference for the academic

subjects as the students showed the previous year. Also there

appears to be relatively little difference between the preferences

of boys and girls. Even the grade level differences are not great

except in such subjects as art, where there is marked loss of

interest at the higher grade

levels.There is greater variety in the reading interest patterns

than in the case of school subjects preferred. In general, these

interest patterns showed remarkable uniformity between types of

schools. There was a marked similarity between interests of both

boys and girls, except in the case of cowboy stories and fiction.

Public school students appear to be more interested in mystery

stories than are the students in Indian schools, and less interested

in current affairs than students in Indian

schools. Students in all types of schools showed a high degree

of interest in comic books at the fourth grade level, with this

interest declining by the time the student hod reached the twelfth

grade.

The tabulated results of the multiple choice leisure time interest questionnaire

of the 1946 study are given in Table III-10. There is a surprisingly high percentage

of students in all types of schools claiming interest in work activities.

The two areas, hobbies and social activities, attracted

the preference of only an extremely small number of students. It must be remembered

that these were the preferences expressed by students and that there was no

measure of the possible influence of responding, in a school situation, to

the type of activity which the student believed was the desired response.

Table III-11 indicates the percent of students of each of the grade levels

tested who expressed o desire to complete eighth grade, senior high school,

trade school, or college. Less than one percent of the fourth grade students

indicated the intention of withdrawing from elementary school before the completion

of eighth grade. Ninety-four percent of the eighth grade students indicated

their intention of completing twelve or more grades. The data concerning present

enrollment suggest the probability that o much smaller per cent of the students

actually complete eighth grade, twelfth grade, or continue beyond high school,

than expressed the intention of doing so. More than three-fourths of the

students in fourth grade indicated their intentions of continuing through

the twelfth

grade, or beyond high school. Present enrollments

indicate that approximately one-fifth of the students actually

do remain in school this long. The fact that the present study

was conducted during the years of the war, when many students

withdrew to enter military service

or war-time employment, makes it impossible to predict the actual

number of students who would otherwise carry out their plans.

The number of students, even at the twelfth grade level, who indicated

their intention of completing college, is surprisingly large. Though

it is possible, particularly at the lower grade levels, that some

students may fail to differentiate between trade school training

and college, the number is so large as to suggest that many do

not recognize that they may not possess the capacity or the tools

necessary

to succeed in college. This observation is borne out by an analysis

of the reading ability of the students in relation to the educational

goal which each indicated. It was discovered that the range of

reading ability of twelfth grade students who did not plan to continue

their education was very similar to that of students who indicated

their intention of going to college. Among the twelfth grade students

indicating their intention of going to college, some of the students

made scores on the Gates

Reading Test, Part A, as low as 7 (Grade Equivalent 3.4). Though

it is possible that the fact that the test was not sufficiently

difficult for some of the best twelfth grade students may have

lowered slightly the median scores, it would appear that the median

score of 19.0 (Grade Equivalent 6.7), as compared with a median

score of 16.6 (Grade Equivalent 6.0) for those who did not intend

to continue beyond the twelfth grade, indicates that many intend

to go to college who do not have the reading skill necessary for

successful achievement in even an academic program in the senior

high school. Though the test may not have measured fully the achievement

of the best students, it was undoubtedly adequate to measure the

reading ability of the majority of the students.

|