Alaska Native in Traditional Times: A Cultural Profile

Project

as of July 2011

Do not quote or copy without permission from Mike

Gaffney or from Ray Barnhardt at

the Alaska Native Knowledge Network, University of Alaska-Fairbanks. For

an overview of the purpose and design of the Cultural Profile Project, see Instructional

Notes for Teachers.

Mike Gaffney

Chapter Eight

Cultural Products

Technology –- hunting/fishing gear, tools, weaponry (and body armor), housing,

transportation.

Applied Science –- specialized knowledge of the regional environment developed to

maintain and improve the group's quality of life.

Artistic Expression –- artistic purposes. design, decoration, materials.

Culture and Its Products

A cognitive definition of culture. In Chapter

Five we discussed the six parts of our concept of culture. When you finished

reading that chapter you may have said to yourself: "But wait a minute! Something

is missing. What about a people's technology and their science and art — the

material things they produced that can be seen and touched?" They are

missing because we consider these visible and material things the products

and reflections of culture, but not basic elements of culture itself. Here

is why.

We employ what is called a cognitive definition of culture.

The term cognition refers to the mental processes of knowing, of reasoning,

of being

aware. Culture is not a physical

thing. It is a mental thing. The elements of social organization, cultural

rules, cultural identity, and worldview are carried about in the minds and

habits of the group's members.

Technology does not come into existence by itself. It cannot stand by itself.

There first must be recognition by someone or some group that a particular

technology is needed or desired

before efforts are made to design and develop that technology.1

Technology

Here we use the term technology to mean those material

products developed by a Native group in order to maintain and improve the

quality of life within their natural and

social environments. Indeed, no other element of your Cultural Profile has

such a direct connection to the process of environmental adaptation than does

technology. This is because

technology furnishes the basic means or instruments of adaptation. Housing,

clothing, tools, weaponry (including body armor), and transportation (kayaks,

canoes, umiaks, dog sleds) are

all things we can actually see and touch. As such, they can have considerable

impact on how we picture a Native group's way of life. It is what first gets

our attention. Any museum we

go to anywhere in the world displays cultural products. This is the main purpose

of muse. But we must be very careful not to assume the material things we

see tells us all we can

learn about that culture.

If technology is not part of our core concept of

culture, then why include it in the Cultural Profile? Remember that the

central purpose of your assignment is to develop a

profile of what life was like in traditional times for an Alaska Native group.

To draw the most complete picture of a people's way of life requires

going beyond basic elements of culture –- social institutions, cultural

rules, and worldview. As already discussed, it requires description of the

natural and social environments to which a Native group had to adapt. Now

we need a description of the technology and science they developed to successfully

accomplish this environmental adaptation.

Cultural products as reflections of cognitive culture.

Although technological products do not fit within our cognitive definition

of culture, they can reflect core cultural

elements. The Central Yup'ik storyknife is a good example of a cultural

product or artifact offering a peek into Yup'ik cognitive culture.* Artfully

carved

out of ivory either by an uncle

or the father, the storyknife became one of a young Yup'ik woman's most

prized possessions. Usually the carvings included decorative symbols and images

of birds. The

storyknife was used mostly by the young woman's grandmother as a teaching

tool. As she told her granddaughter a story of particular cultural significance

to women, she would take

the knife and draw on the ground pictures and symbols to reinforce the

educational

points she was making. So knowing about an Yup'ik artifact such as the

storyknife offers a window

onto aspects of Yup'ik cognitive culture. And we catch a glimpse of several

important social relationships in a young Yup'ik woman's life by knowing

who carved her storyknife and

who was the "educator" who used it. And secondly, we get some sense of the Yup'ik

worldview as reflected in the carved illustrations on the knife and the themes of the stories

told.2

Native Applied Science

Native applied science and a good story. It is not a question of whether traditional

Native societies did "science." It is, rather, a question of what kind of science was done. Here

is a good story to illustrate the point. Awhile back, Alaska magazine had an article entitled

"The Ice Man" by the Anchorage writer, Charles Wohlforth. Here is part of the story he tells

about the late I˝upiaq elder, Mr. Kenny Toovak, who was a longtime employee of the Naval

Arctic Research Laboratory in Barrow before it closed in 1980:

One fine summer morning decades ago,John Kelley, a marine

scientist and later director at Barrow's Naval Arctic Research Laboratory,

went to Kenny Toovak,

who managed the lab's boats and equipment, and asked for a ride out to

Point Barrow in one of the 18-footers with an outboard motor. As the story

goes, Kelley had work

to get done and limited time, and wanted to go right away. Toovak looked

at the sky and told him, with typical I˝upiaq indirectness, "I'd like

for you to wait a bit."

Kelley didn't insist at first, but paced around

impatiently, making it clear he needed to go soon and saw no reason to

wait. The weather looked perfect.

In 15

minutes, he returned and told Toovak that it was time to go.

Toovak, a skilled storyteller who can draw out every detail

in a slow, dignified style, said he told Kelley, "You really want to

go out, I'm going to give you a boat and an outboard. You can go. But I'm

no going to

give you a driver. And I don'

think we're going to look for you, even. You really want to go out,

go on and go.'

Kelley returned to his office. Shortly, the wind picked

up. It was soon howling, with white caps frothing on top of the waves.

He returned

once again and

said, "Kenny, I thank you for not sending me out."

Scientists and the I˝upiaq of Barrow have worked together,

on and off, for 150 years; similar incidents may have happened many times

as Eskimos

kept

scientists safe and taught them about the natural history of the Arctic.

Toovak's story stands out because hardly anyone has done as much to

bring I˝upiaq knowledge

to science, and because, in his early 80s, he is still teaching. Changes

in the arctic

climate have become a topic of scientific urgency and Toovak's memories

have attained special value.

Some scientists would like to reverse- engineer

the skill of Eskimo elders, hoping that the signs and patterns that elders

use would help researchers

understand

nature as well. But it's not easy to dissect the magic of what an old

man feels in his bones.

When asked what he saw that day with John Kelley

decades ago, Toovak said, "It was something about the sky, the clouds

and south wind, a bit warm. It's always kind of rapid, it always happens

in a rapid way. I

learned that lesson from my

parents and from the elder people. When the wind is kind of

blowing from the south you better hold off for a while and see what the

weather

will do."

Elders across the Arctic have told researchers that the

weather has become erratic and more difficult to predict since the

climate started

to change in the past two

decades. Atmospheric scientists following up on these observations

agreed that the weather is more changeable and cyclonic storms

have

become more frequent in the

Arctic, shorting times of stability and perhaps breaking the rhythm

of the winds that the elders had learned to anticipate. 3(pp.

42-43)

How did Mr. Toovak learn to anticipate changes in Arctic weather

so precisely? He said he learned this special knowledge from his parents and

other elders as he grew up. And,

of course, they learned to do weather forecasting from the generation before

them. What is clear is that at some point in the distant past, perhaps over

several generations, the North

Slope I˝upiaq carefully studied these weather patterns. Their very survival

in Arctic waters and on sea ice depended on reliably forecasting changing

weather conditions. In the language

of modern science, it depended on developing special knowledge of meteorology,

the study of the earth's atmosphere, especially its patterns of climate and

weather. In another section of

his story about Mr. Toovak, Mr. Wohlforth tells us that many of today's

scientists now take very seriously I˝upiaq knowledge of changing Arctic weather

patterns and seek ways to fit this traditional Native science into their own

work. Scientists also have begun to incorporate

I˝upiaq traditional knowledge into other aspects of their work on the

Arctic ecosystem. An example is how traditional I˝upiaq knowledge of

Bowhead Whale behavior has changed the way scientists look for and count

current whale populations.

Wohlforth also says that "it's not easy to

dissect the magic of what an old man feels in his bones." But it is

really not magic at all. What Mr. Toovak "feels in his bones" is a

confidence to apply a specialized body of knowledge built upon generations

of very careful study of Arctic weather. What seems like magic was Mr.

Toovak's special talent for applying

I˝upiaq meteorology so effectively. It has all the elements of what

today is called applied

science. Applied science develops in situations where, first,

a problematic condition like sudden weather changes has been identified.

Then members of the group seek the knowledge

necessary to understand the problem. Over time they develop a body

of

specialized knowledge and learned to directly apply this

knowledge to whatever health, security, or welfare issue confronts

the group.

Applied versus basic science. Because it is

concerned with solving immediate problems, applied science has a purpose different

from basic science. Basic (or pure or

theoretical) science does not seek a solution to an urgent problem. Its purpose

is to study a particular phenomenon simply because it exists and greater

understanding of it would

advance scientific knowledge generally. In formulating his universal law

of gravitation, for example, Sir Isaac Newton only wished to understand

why objects fell to the earth at

accelerated rates and why the moon and other heavenly bodies maintained their

positions in space. His purpose was not to meet an immediate need

or desire of English society.

Eventually the theories and findings

of basic science may contribute to solving immediate problems, but that is

not the original intention.

All the basic

science done over

many years on the chemistry of gases, for example, contributes to understanding

and hopefully reducing green house gases, including their impact on the

Arctic. But we can be

certain that the scientists who developed the first theories of gases such

as Robert Boyle in 1662 and Joseph Gay-Lussac in 1802 did not have greenhouse

gases and Arctic warming in

mind. Because specialized Native knowledge developed as an immediate response

to the problems and opportunities of the environment, applied science seems

the more appropriate

term.

Specialized knowledge. We have made the point

that Mr. Toovak had a unique talent for applying a specialized body of I˝upiaq

knowledge to understanding Arctic weather patterns. But what is specialized

knowledge? The answer becomes clear when we separate

specialized knowledge from common knowledge.

In order to live successfully

within their natural and social environments, all members of a traditional

Native group had to know a body of common

knowledge and be able to apply

it to their daily life. At a minimum, this common knowledge included

obtaining and preparing food, having and raising children, coping with illness,

and

knowing how to deal

with the opportunities and dangers of the surrounding environment. It

also included knowing how to maintain in good working condition such cultural

products as tools, housing, clothing,

modes of transportation, and hunting and fishing gear. Of course most

of

this list can be applied to life generally because it covers the timeless

and essential

requirements for living in

the world. After all, doesn't everyone down through time need food, clothing,

shelter, health

care, and child-rearing skills?

So the question becomes: Beyond common

knowledge, was there knowledge needed or valued by the group which could

only be developed

with special talents and special

methods of study? Where we discussed common knowledge and cultural

products above, we were careful to avoid the verbs "to construct" or "to

build." We only used the verb "to

maintain." We said that common knowledge was required to

maintain various

cultural products. Why? Because many times the design and

construction of essential products was

not done by just any man or woman. They were done instead

by individuals who became specialists in a particular art

or craft.

The traditional Aleut kayak, for example, is still

considered by master boat builders around the world to have

the ultimate

design

for speed

and maneuverability of a one and two

man ocean-going paddle craft. Just imagine what special knowledge

was required to design a kayak that would withstand the

often furious

currents

and winds of the North Pacific along

the Aleutian chain of islands. These ancient Aleut craftsmen even

designed a bilge pump allowing the kayaker to suck out sea

water that

sloshed into the kayak. Although the Kayak (

or baidarka in Russian) was an essential Aleut cultural

product operated and maintained by many, only some had the special

talent and

training for its design and construction. Another

example is the intricately carved totem or house poles of the Tlingit

and Haida. Again, a needed and valued cultural product requiring

special talents

in art and woodworking only

possessed by some.4

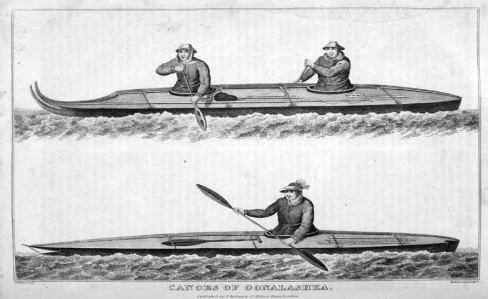

Figure 8-1

This drawing from

Captain Cook's 1778 voyage to Alaska shows Aleuts in double and single hole

kayaks. The men are wearing traditional waterproof skins. The man

in the single man kayak is also wearing the distinctive Aleut

sea visor with feathers. [From: Alaska Digital Archives.]

Specialized knowledge can become common knowledge. Over

time aspects of specialized knowledge can become common knowledge. The internal

combustion engine, for

example, is a scientific invention of the mid 1800s that became part

of everyday life. Among other things, it powers the various vehicles we use

daily — autos, trucks, ships, boats,

airplanes, and snow machines. If it requires fuel to run, it is an

internal combustion engine. If you wish to be a well trained mechanic, you

would likely take courses in such areas as

"engine thermodynamics," "heat transfer in engines," and "fluid mechanics." Obviously

this is all very specialized knowledge acquired by relatively few people after

serious study. But

because the internal combustion engine is so essential to our daily

life, many of us know enough about it to perform fairly complicated maintenance

and repair operations. We may

not be able to explain engine thermodynamics, but we do know about

carburetors, pistons, spark plugs, fan belts, engine blocks, and the need to

change the oil according to the season.

And probably we know the difference between 2 stroke and 4 stroke

engines. We need to know these things if we are to keep the motors of our fishing

boat and snow machine in good

working order. All of this has become common knowledge necessary

for living as a modern subsistence hunter, trapper, and fisherman

in Alaska.

One measure of how much an area of specialized knowledge has

become common knowledge is the extent to which it is part of our everyday

language. We even use some of

this language as metaphors — she is the "spark plug" of the high school

basketball team. This vocabulary did not exist before the invention of the

internal combustion engine. It had to

be invented along with the engine itself. As you read this chapter,

you can bet that somewhere vocabulary is being invented to keep up with the

rapidly expanding information

technology of computers and the internet. Not too long ago, nobody

heard of "apps" or

"blog" or "twitter."

In the course of developing specialized knowledge, traditional

Native societies also had to invent specialized vocabularies. And over time

these new words

became common

knowledge and part of the language of everyday life. An good example is the

set of thirty- one Inuit words establishing a detailed classification system

for various conditions of snow.5 Here are some of those words:

| Aluiqqaniq: Snowdrift on a steep hill, overhanging on top. |

Anuik: Snow for drinking water. |

| Aput: Snow on the ground (close to the generic snow) |

Aqilluqqaaq: Fresh and soggy snow |

| Auviq: snow brick, to build igloo |

Ijaruvak: Melted snow |

| Isiriartaq: Falling snow, yellow or red. |

Kanangniut: Snowdrift made by North-East wind. |

| Katakartanaq: Crusty snow, broken by steps. |

Kavisilaq: snow hardened by rain or frost. |

| Kinirtaq: wet and compact snow. |

Masak: wet snow, saturated. |

| Matsaaq: snow in water |

Maujaq: deep and soft snow, where it's difficult to walk. |

| Mingullaut: thin powder snow, enters by cracks and covers objects. |

Mituk: small snow layer on the water of a fishing hole. |

| Munnguqtuq: compressed snow which began to soften in spring. |

Natiruviaqtuq: snow blasts on the ground. |

| Niggiut: snowdrift made by south-west wind |

Niummak: hard waving snow staying on ice fields turned in ice crystals. |

Notice how just one Inuit word highlights a condition of snow requiring several

English words. Like the English words used to capture the functions of the internal

combustion engine, this Inuit classification of snow conditions is a good example of

specialized knowledge becoming common knowledge.

The scientific method. Along with specialized

knowledge, a definition of science must include the process by which scientific

evidence is obtained and theories tested. This

process is called the scientific method. The key idea

here is contained in the verb "to do." If

people anywhere at any time follow a series of well defined steps

to understand some aspect of the natural or social world, they are doing science.

They are using the scientific method. The I˝upiaq who painstakingly

developed the metrological knowledge Mr. Kenny Toovak relied upon

that fateful day used the scientific method which is ordinarily

thought of as

consisting of two parts. The first part is attitude. Is

the attitude of the investigator working on a scientific problem

such as Arctic warming dedicated to rational thinking? That is,

does he

use logic and reason rather than emotional, magical, or spiritual

thinking when making his observations and drawing his conclusions?

Is the attitude of the investigator objective? Is he

willing to go wherever the facts take him although it may contradict

strongly held beliefs? Is he open to new evidence and ideas even

if they may prove his current theory wrong?

Many consider the scientific

method to be the major difference between matters of science and

matters of faith. Religious doctrine

such as belief in God and a supernatural

world cannot be empirically tested –- that is, proven right or wrong

by real life observation and experimentation. But this does not mean a reasonable

person schooled in the scientific

method cannot also conclude that a well ordered universe with no

apparent middle or edges suggests the existence of a supreme being or ultimate

creative force. Albert Einstein, the

scientist best known for his theories on how the universe works,

believed exactly this. Responding to the question of whether he believed in

God, Einstein said, "I believe in

a...God who reveals himself in the orderly harmony of what exists,

not in a God who concerns himself with fates and actions of human beings." 6 But

most important, he never claimed that his scientific work proved

or disproved the existence of God. Certainly he would be

the first to say that science was never meant to answer questions

of faith and how the faithful should imagine a supernatural world.

That world must be thought about and approached in other

ways.

The second part has to do with method — the

actual process of doing science. Is the information (the data)

gathered by the investigator accomplished through a series of

deliberate and well organized observations of the phenomenon under

study? A fundamental rule of the scientific method is that theories

must be constructed so that their propositions can

be further tested by others under the same conditions using the

same methods. Usually scientific proof is based on empirical evidence.

Interior Athabaskans, for example, developed

a method for hunting caribou by chasing the animals into large

corrals where they were

"speared, snared, and shot with arrows." 7 It is easy to imagine

how different "chase

methods" were empirically tested before finding the most effective

method. Or their testing of different materials used for constructing

the corral before finding one that was easy to

work with but strong enough to hold frightened caribou. And Mr.

Kenny Toovak's story certainly gives us some idea of how the

I˝upiaq applied the scientific method to the study of

weather in much the same way Albert Einstein studied the universe.

Ancient Alaska Native societies did not have written scientific

journals to record and organize their research. Their

oral traditions served this function. Certainly they did not have

the scientific instruments available to Albert Einstein and other

modern scientists. Even so, they could not have

accomplished such extraordinary adaptations to the unique challenges

of their environments without applying what today we call the

scientific method.

Medical science. We must not forget that traditional

Native cultures also used the scientific method to advance their understanding

of the

human body and medical treatment of

it. Aleuts (Unagan), for example, performed autopsies to increase their understanding

of human autonomy and causes of death. They also developed an

inventory of herbal cures —

in modern terms, a pharmacy — derived from the precise mixing of substances

taken from various plant life found within the Aleutian regional environment.

Aleut medical science also

allowed development of a special feature of their worldview

found on several Aleutian islands — the practice of mummification

to memorialize the spirit of a deceased person of high social standing or

for extraordinary accomplishments in life. Only through rigorous

empirical study could such a body of knowledge be achieved.8 In

discussing traditional medicine among the Yup'ik, Oscar Kawagley

directly connects the development of this

knowledge to application of the scientific method. After describing

several complex and lengthy treatments for arthritis, he says:

The experimental process leading to the development of a treatment such as

this [arthritis] had to occur over a very long period of time before its medicinal value

was recognized. This required experimentation, using the rational ability of the human

being, establishing a process for refining a natural substance, using very practical

means at hand, observing and committing to memory the process of change in the

solution [for treating arthritis], and noting the effects on the human body for

determination of its effectiveness.9

As we know, shamans often performed the dual role of spiritual leader and

healer of both physical and mental health problems. In fact, many traditional

Native worldviews did

not clearly separate spiritual issues from health issues. In many

cases, physical and mental illness was viewed as a sign of possible spiritual

disharmony within the community or within

the individual who is sick. Some shamans were even thought to

have the power to create this disharmony and make people physically or mentally

ill. But no matter how this dual role was

performed within a specific Native culture, shamans and other

prominent healers used elements of the scientific method to advance their medical

knowledge.

Artistic Expression

What is Art? A main cultural product of any society is its Art.

A people's values,

traditions, and aspirations are often expressed through powerful artistic imagery. Of all the

elements that make up any society's cultural production, it is art which most clearly reflects

aspects of that society's worldview. The Sistine Chapel at the Vatican in Rome, Italy is an

excellent example of how art is used to visualize a major religious tradition, in this instance

the Roman Catholic tradition. Its interior is covered with paintings of biblical stories done by

Italian renaissance artists, including the ceiling painted by the renowned Michelangelo, a

section of which is shown in figure 8-2.

Figure 8-2

Michelangelo's ceiling at the Sistine chapel10

In our earlier discussion of the Central Yup'ik storyknife, we said

that the imagery

carved on the ivory handle was an example of how this Yup'ik artifact can give us a glimpse

of Yup'ik cognitive culture. But at the same time it is equally an artistic product. Like all art,

the images carved into the storyknife handle were meant to represent an idea or series of

ideas. The father or uncle who did the carving was perhaps expressing a significant thought

for the young girl to keep in mind as she anticipated adult female responsibilities.

Where do we find traditional Native Art? The storyknife gives us a major clue

to finding and describing traditional Native art. Unlike art collections found

in modern

museums, in traditional times we would not find separate structures

housing pieces of a Native group's art to be contemplated and admired. What we would find is artistic expression

displayed in the decoration and design of material objects having other functions. Remember

that the Yup'ik storyknife was also crafted to serve an educational purpose. Also within the

Central Yup'ik artistic tradition is expression of their supernatural world through the design

and decoration of ceremonial masks. Just as the art of the Sistine Chapel vividly displays

elements of the Roman Catholic tradition, the art of ceremonial masks vividly displays

aspects of the Yup'ik spiritual tradition. Figure 8-3 below shows a Nepcetaq (shaman mask)

with face peering through a triangular shield, painted red, white, and black. Red sometimes

symbolized life, blood, or give protection to the mask's wearer; black sometimes represents

death or the afterlife; and white sometimes can mean living or winter. 11

Figure 8-3

Yup'ik Shaman Mask

We even find art in decorative designs fastened or sewn onto

clothing. For interior Athabaskans whose life was almost constant movement,

their cultural products had to be

easily transported on one's back or in bags carried by dogs. Of course they also had to be

easy to assemble and disassemble. One scholar of Native art, William Fitzhugh, says of

Athabaskan clothing that "most outstanding was their skin work,

which employed dyed

porcupine quill and moose hair embroidery in its early stages

and, later, glass beads, dentalium shell, and other trade goods." 12

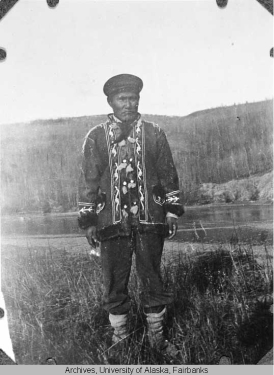

Figure 8-4

Albert Maggie with beaded coat. Nenana, Ak., c. 1913)

Here we should highlight what we said earlier about the importance of commerce

in traditional Native economies. Because these pre-contact commercial networks

reached

beyond Alaskan borders, many of the decorative beads and shells

were acquired by interior Athabaskans before their actual encounters with Europeans.

Dentalium seashells, for

example, are found along the northwest coast of North America.

They are usually white and hollow inside and cone shaped like a tooth or tusk.

They were so highly valued by Indians

from California to Alaska that they became a medium of exchange

much as we use dollar bills and coins today. Look at the photo of a Tlingit

shaman in the last chapter (p. 81).

Dentalium shells decorate his apron-like leg covering .

What we learn from Native art. We have said that art serves as a window through

which we can view elements of people's worldview. But art forms can also differ

between

otherwise similar cultural groups. William Fitzhugh has observed

that Central Yup'ik art "was more diverse, abstract, and symbolic than that of the I˝upiaq peoples." The exquisite

and celebrated I˝upiaq art of ivory carving portrayed life in

its natural form. An outsider knows at once that it is a carving

of a polar bear or a whale or a seal. On the other hand,

making sense of the more abstract and symbolic Central Yup'ik

decorative art requires knowledge of their worldview, particularly

aspects of their traditional spirituality.13

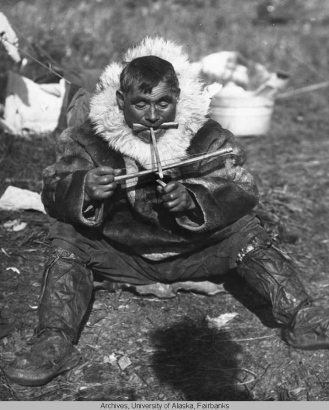

Figure 8-5

Little Diomede I˝upiaq ivory carver, c. 1928

We also learn that some Native art crossed territorial boundaries. One of

the best known and most studied of all Native American art forms is the Northwest

Coast Indian

tradition. This very distinctive Native art stretches 1,200

miles along the Pacific Coast from Oregon in the south to the Tlingit and Haida

homelands of Alaska in the north. Although

speaking different languages, these Northwest Coast tribes had

in common a heavily wooded temperate maritime environment, a clan-based hierarchical

social organization, and a totemic

worldview with Raven at the center of their creation mythologies.

Andrew Hope III, refers to this entire Northwest culture area as the "Raven Creator Bioregion." Perhaps one of the most

knowledgeable experts on Northwest Coast Indian art is University of Washington Professor

Emeritus, Bill Holm. For his distinguished work, he was honored in 2001 with a certificate of

appreciation from the Sealaska Heritage Institute, an organization which seeks to perpetuate

and enhance Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian cultural knowledge. Holm characterizes Tlingit

and other Northwest Coast Indian art as a well organized design system of ovid-shaped form

lines depicting totemic creatures central to the mythological histories of clans and of house

groups within clans. The Chilkat blanket shown below is a good example of the description

Holm gives of the Northwest Coast Indian art form14

George Emmons, a United States Navel officer who carefully observed Tlingit

life in the late 1800s, reported that ceremonial blanket-weaving originated

with the Canadian

Tsimshian and later spread north to the Tlingits through commerce

and marriage. Settled near the present day town of Haines, Alaska, the Chilkat

tribe of Tlingits developed their

own design style and became the best weavers, producing numerous

blankets for clans and

clan houses of other Tlingit groups. The Chilkat Blanket was

highly sought by Indian nobility up and down the Northwest Coast long before

the first explorers came to the

region.15

Figure 8-6

Chilkat Blanket

A detailed artistic depiction of a totemic creature along with

other clan or clan house symbolism is called a crest. Here is another good

example of art teaching us something about

the society in which it is found. In this case we learn about

the connection between Tlingit

social organization and Tlingit art. Again we go to Andrew Hope III for instruction:

To appreciate Tlingit pole art, one must understand Tlingit social

organization: what Frederica de Laguna refers to as ." . . the fundamental principles

of . . . clan organization, . . . the values on which Native societies are based," that is,

the names and histories of the respective Tlingit tribes, clans, and clan houses.

The seventy-plus Tlingit clans are separated into moieties or two equal

sides - the Wolf and the Raven. Tlingit custom provides for matrilineal descent

(one follows

the clan of the mother) and requires one to marry one of the

opposite moiety. The clans are further subdivided into some 250 clan houses.

To underscore the duality of Tlingit law, Wolf moiety clans generally claim

predator crests, whereas Raven moiety clans generally claim non-predator

crests. For

example, the Kaagwaantaan, a Wolf moiety clan, claim Brown

Bear, the Killer Whale, the Shark and the Wolf as crests. The Kiks.ßÓdi, a

Raven moiety clan, claim the Frog, the Sculpin, the Dog Salmon

and the Raven as crests. Tlingit totem art is

utilitarian as opposed to decorative art. Tlingit pole art

depicts clan crests and histories.

The figures seen on a totem pole are the principle subjects

taken from traditional treating of the family's rise to

prominence or of the heroic exploits of one

of its members. From such subjects crests are derived. In

some houses, in the rear between the two carved posts, a

screen is fitted, forming a kind of partition which is

always carved and painted.16

According to traditional Tlingit property laws, moreover, a clan or clan house

has clear ownership of their crest and it can be used only by their members.

Elements of the crest

ornamented other cultural products such as house poles, screens,

war canoes, headgear, boxes and chests, and even parts of hunting and fishing

equipment. In some ways a European

noble family's coat-of-arms is comparable to the Tlingit clan

crests because it also exhibits

symbolism of the family's honored history and mythological beginnings.

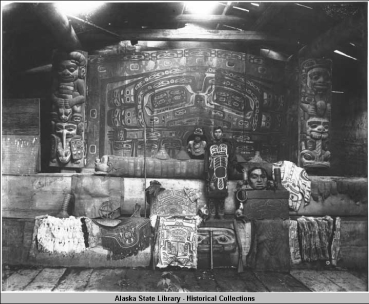

Figure 8-7 shows the interior of Tlingit clan house emblazoned with carved

clan crest and symbols. Note the

pole art discussed above by Andy Hope. Also note the ovid-shaped

form lines described by Bill Holm. For a European comparison, the British Royal

Family's coat-of-arms or crest is

also shown below. 17

Figure 8-7

Interior of Whale House of Chief Klart-Reech, Klukwan, Alaska.

c. 1895.

British Royal Family's coat-of-arms

Not only did the ovid-shaped form lines of Northwest Coast Indian art extend

1,200 miles south to Oregon, but it also influenced the artistic

expression of other Alaska Native groups along the North Pacific Rim. We

know that hostilities sometimes existed between the

Tlingit and other Pacific Rim peoples. Yet studies by Bill

Holm and others show that the

Chugach of Prince William Sound and the Koniag of Kodiak Island

adopted certain elements of the Northwest Coast artistic tradition to decorate

their basketry, headdress, storage chests,

and eating utensils. Indeed, the spread of the unique Northwest

Coast Indian art form offers yet another example of Native people traveling

great distances to exchange both goods and

ideas. 18

An interesting artistic comparison. According to historical records, it took

Michelangelo about four years to complete his ceiling at the Sistine Chapel.

In all,

Michelangelo's work covers 5,000 square feet. (A NBA basketball

court measures 4700 sq. feet.) By comparison, in 1998 Clarissa Hudson, a

master Chilkat blanket weaver, began

weaving a blanket for a Canadian Native chief. As she says, "Between caring for my family,

finishing my other commissions, and moving (twice!) I finished the blanket in just over two

years." 19 Let's assume Clarissa spent a quarter of her time on the chief's blanket while

attending to other parts of her full life. If this is a reasonable assumption, it means that if she

were able to work full time on her blankets, she still could only weave four 25 sq. foot

Chilkat blankets in the time it took Michelangelo to complete his 5000 sq. foot Sistine

Chapel painting.

Review Questions

Cultural products are not a basic part of our concept of culture? Why

not?

Why do we say it is not a question of whether Alaska Natives did

science in traditional times, but a question of what kind

of science was done?

Why distinguish specialized knowledge from common knowledge?

(Hint –- the connection between science and specialized knowledge.)

Can you explain the scientific method, and why we say it is not just a

modern or Western practice, but has been used down through

time by all peoples?

Why do we say: "Of all the elements that make up any society's

cultural production, it is art which most clearly reflects aspects of that

society's worldview? Can you give examples from Alaska Native

cultures?

Give some reasons why we must look for traditional Native art on

cultural products having other functions.

* The term artifact refers to a material object made by humans and, therefore,

a cultural product from times past.

ENDNOTES

-

Erickson, Frederick, "Culture in society and in educational

practices" in J. Banks and C. Banks

(Eds.)Multicultural Education –- Issues and Practices,

John Wiley & Sons; 5 ed. ,2001).

- Ann Fienup-Riordan, Crossroads of Continents, Smithsonian

Institution Press, 1988, p. 262, and Steve Langdon,

Native People of Alaska, 2002, p. 52.

- Charles Wohlforth, "The Ice Man", Alaska Magazine, October

1, 2004, pp. 42-43.

- Black, Lydia and R. G. Liapunova, "Aleut: Islanders of

the North Paciific"in W. Fitzhugh &

Crowell (eds.), Crossroads of Continents, Smithsonian Institution Press,

1988, p. 55

- Go to:http:-//www.athropolis.com/links/inuit.htm

- Ronald W. Clark, Einstein: The Life and Times (Canada: World Publishing

Co., 1971), p..502.

- Richard K. Nelson, "Raven's People" in J. Aigner, Ed. Interior

Alaska (Anchorage: Alaska Geographic Society, 1986) p. 206.

- Laughlin, William S. Aleuts: Survivors of the Bering

Land Bridge (Harcourt Brace College Publishers June 1980),. Steve

Langdon, 2002, p. 24. Black, Lydia and Liapunova, 1988, pp. 53.

- Kawagley, A Yupiaq Worldview (Illinois: Waveland Press,

1995) pp. 71-72.

- Go to: academics.skidmore.edu/../the infamous ro.html

- Arctic Studies Center Exhibit: "Agayuliyararput,

Our Way of Making Prayer."

(www.mnh.si.edu/arctic/features/yupik/index.html

- Fitzhugh, W., "Comparative Art of the North Pacific Rim" in W.

Fitzhugh & Crowell

(eds.), Crossroads of Continents, Smithsonian Institution Press,

1988, p. 304.

- Ibid, p. 301.

- Sheldon Museum and Cultural Center, Haines, AK.

(www.sheldonmuseum.org/chilkatblanket.htm)

- Emmons, George Thorton, The Tlingit Indians, (Fredrica

de Laguna, ed.), University of Washington Press, 1991

- Andrew Hope III, Andy Hope, "Southeast Region:

Reading Poles" in Sharing Our Pathways, A

newsletter of the Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative.

Volume 3, Issue 5, 1998.

- Go to: http://www.britroyals.com/arms.htm

- Holm, Bill, "Art and Culture Change at the Tlingit –-

Eskimo border" in W. Fitzhugh &

Crowell (eds.), Crossroads of Continents, Smithsonian Institution Press,

1988, pp. 281 –-

293

- Go to: Clarissahudson.com

Table of Contents | Congratulations

& Biliography