|

Indigenous Knowledge Systems

and Higher

Education:

Preparing Alaska Native PhD's

for Leadership Roles in Research

Native

PhD's for Leadership Roles in Research. To be published in Canadian Journal

of Native Education (Winter, 2009).

Abstract: Native peoples in Alaska have

usually been the subjects of research rather than the ones responsible for

conducting it. However, the role of Alaska

Natives in research is changing due to a concerted effort on the part of

the University of Alaska and Native people themselves to develop new programs

aimed

at recruiting and preparing Native scholars in all academic fields who can

take on leadership roles and bring an Indigenous perspective to the policy

arenas at the local, state, national and international levels. This article

will describe the activities underway, their rationale, and the implications

for research.

Key words: Indigenous Education, Alaska Natives, Traditional

Knowledge, Higher Education

INTRODUCTION

Indigenous peoples throughout the world have sustained their unique

worldviews and associated knowledge systems for millennia, even while undergoing

major social upheavals as a result of transformative forces beyond their

control.

Many of the core values, beliefs and practices associated with those

worldviews have survived and are beginning to be recognized as having

an adaptive

integrity that is as relevant for today’s generations as it was

for past generations. The depth of Indigenous knowledge rooted in the

long

inhabitation of a particular

place offers insights that can benefit everyone, from educator to scientist,

as we search for a more satisfying and sustainable way to live on this

planet.

Actions taken by Indigenous peoples themselves over the past twenty

years have begun to explicate Indigenous knowledge systems and ways

of knowing

in ways

that demonstrate their inherent validity and adaptability as complex

knowledge systems with a logic and coherence of their own. As this

shift evolves,

it is not only Indigenous people who are the beneficiaries, because

the issues

that are being addressed are of equal significance in non-Indigenous

contexts (Barnhardt and Kawagley 2005). Many of the problems that

are manifested

under conditions of marginalization have gravitated from the periphery

to the centre

of industrial societies, so the new insights that are emerging from

Indigenous societies are of equal benefit to the broader community.

The tendency in past education and research initiatives aimed at engaging

Indigenous people, most of which were designed from a non-Indigenous

perspective, has

been to focus on how to get Indigenous people to understand the

western/scientific view of the world. Until recently there was very little

attention

given to how western scientists and educators might better understand

Indigenous

worldviews,

and even less on what it means for participants when such divergent

systems coexist in the same person, organization or community.

It is imperative,

therefore, that we come at these issues on a two-way street, rather

than view the problem

as a one-way challenge to get Indigenous people to buy into the

western system. Indigenous people may need to understand western society,

but not at the

expense of what they already know and the way they have come to

know it. Non-Indigenous

people, too, need to recognize the co-existence of multiple worldviews

and knowledge systems, and find ways to understand and relate to

the world in

its multiple dimensions of diversity and complexity.

BACKGROUND

The aspirations of Indigenous peoples extend beyond serving in

a passive or advisory role in response to someone else’s

policy or research agenda - they include shaping the terms of

that agenda and serving as active participants

in its implementation. One of the most persistent constraints

in fulfilling those aspirations is for Indigenous peoples to

be recognized as having the

qualifications and expertise to be valued partners in the research

and policy-making process. The strategy to overcome those constraints

has focused on the preparation

of Indigenous scholars who have a high level of research and

policy expertise and an in-depth understanding of the dynamics

at the interface between Indigenous

knowledge systems and western institutions.

In 2004, the Arctic

Council issued the Arctic Human Development Report (AHDR)

which highlighted the following as significant

factors influencing

the lives

of Indigenous peoples of the Arctic: controlling one’s

own destiny; maintaining cultural identity; and living close

to nature (Arctic Council 2004). Key to

alleviating the negative effects and strengthening the positive

contributions of these factors in peoples’ lives and well-being

is the need for education and research efforts initiated in the

Arctic by Indigenous peoples themselves

and by local institutions. As indicated in the AHDR:

Economic

models and policies in modern Arctic societies are traditionally

designed and legitimated in administrative and political institutional

contexts outside

the Arctic. A key concern of future research should be to have

a critical look at these contexts aiming at gaining new grounds

for

decision-making

. . . Indigenous

peoples of the Arctic have managed to carve out political regions

in which they make up the majority, or at least a significant

part of

the population.

Based upon this reality, Indigenous peoples and communities are

now actively involved in setting research agendas. It is thus

obvious that research

agendas set by Indigenous peoples themselves or reflecting Indigenous

cultures will

be a key factor in setting research priorities for the next decade

(Arctic Council 2004).

While these issues are of critical concern

for Indigenous peoples and communities in the circumpolar region, their significance

is by no

means limited to

the Arctic—these are issues of broad international importance,

as reflected in the United Nations report on the Status

and Trends Regarding the Knowledge,

Innovations and Practices of Indigenous and Local Communities (Helander-Renvall

2005).

Recognizing the need to address these issues in a systematic

way, the U.S. National Science Foundation, Office of Polar

Programs convened a “Bridging

the Poles” workshop in Washington, D.C. in June,

2004, bringing together scientists, educators and media specialists

to outline an education and research

agenda for the International Polar Year (IPY). Among their

recommendations was the following: “Communication with

Arctic Indigenous peoples must include developing a new generation

of researchers from the Arctic who actively

investigate and communicate northern issues to global populations

and decision makers….” (Pfirman et al. 2004).

The

workshop participants then outlined the following objectives

regarding the engagement of diverse communities:

-

Arctic residents, including Indigenous populations, are meaningfully engaged

in developing and implementing polar research, education, and outreach, including

community concerns and traditional knowledge, with an increase in the number

Arctic residents—especially Indigenous Alaskans—with

PhDs.

- Focus on building capacity within Indigenous communities

for conducting research (including local collection of data) and education/outreach

in both traditional

and nontraditional venues. Community-based educational

components

should be developed for existing and planned long-term observation networks, … tailored

by community members to address community relevant issues,

and to involve both native elders and scientists. Arctic research projects by

Native people, for

Native people, will involve finding funding sources and connecting

them with Native communities.

-

Recognizing that the Native peoples have knowledge and tradition

to share with other populations is an important first step towards

their involvement. Their

presence in the field of education, both traditional and non-traditional,

will assist in encouraging more Natives, and in providing a bridge

to other cultures… (Pfirman

et al. 2004).

Since western scientific perspectives influence

decisions that impact every aspect of Indigenous peoples’ lives,

from education to fish and wildlife management, Indigenous people

themselves have taken a strong active role in

re-asserting their own traditions of science in various research

and policy-making arenas. As a result, there is a growing awareness

of the depth and breadth

of knowledge that is extant in many Indigenous societies and

its potential value in addressing issues of contemporary concern,

including the adaptive

processes associated with a rapidly changing environment.

The

incongruities between western institutional structures and practices

and Indigenous cultural forms are not easy to

reconcile.

The complexities

that

come into play when two fundamentally different worldviews

converge present a formidable challenge. The specialization,

standardization,

compartmentalization,

and systematization that are inherent features of most western

bureaucratic forms of organization are often in direct conflict

with social structures

and practices in Indigenous societies, which tend toward

collective decision-making, extended kinship structures, ascribed authority

vested in elders, flexible

notions of time, and traditions of informality in everyday

affairs (Barnhardt 2002). It is little wonder then that western

bureaucratic

forms have

been found

wanting in addressing the needs of traditional societies.

Indigenous

societies, as a matter of survival, have long sought to understand

the irregularities in the world around them,

recognizing that nature

is underlain with many unseen patterns of order. For example,

out of necessity,

Alaska

Native people have long been able to predict weather based

upon observations

of subtle

signs that presage what subsequent conditions are likely to

be. With the vagaries introduced into the environment by accelerated

climate

change in recent years,

there is a growing interest in exploring the potential for

complementarities

that exists between what were previously considered two disparate

and irreconcilable

systems of thought (Krupnik and Jolly 2001; Barnhardt and Kawagley

1999).

INTERSECTING WORLD VIEWS: THE ALASKA EXPERIENCE

The sixteen distinct Indigenous

cultural and linguistic systems that continue to survive in communities throughout

Alaska

have a rich

cultural history

that still governs much of everyday life in those communities.

For over six generations,

however, Alaska Native people have been experiencing recurring

negative feedback in their relationships with the external

systems that have

been brought to

bear on them, the consequences of which have been extensive

marginalization of their knowledge systems and continuing

dissolution of their

cultural integrity. Though diminished and often in the

background, much of

the Native knowledge

systems, ways of knowing and world views remain intact

and in practice, and there is a growing appreciation of the contributions

that Indigenous

knowledge

can make to our contemporary understanding in areas such

as medicine,

resource management, meteorology, biology, and in basic

human behavior and educational

practices (Kawagley et al. 1998; James 2001).

In an effort

to address these issues in a more comprehensive way and apply new insights

to address long-standing and

seemingly intractable

problems,

in 1995 the University of Alaska Fairbanks, under contract

with the Alaska Federation

of Natives and with funding support from the National

Science Foundation Rural Systemic Initiative Program, entered into

a ten-year applied

research endeavor

in collaboration with Native communities. The activities

associated with the Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative

(AKRSI) were aimed

at fostering connectivity and complementarities between

the Indigenous knowledge

systems

rooted in

the

Native cultures that inhabit Alaska and the formal education

systems

that have been imported to serve the educational needs

of Native communities.

The underlying

purpose of these efforts was to implement a set of research-based

initiatives to systematically document the Indigenous

knowledge systems of Alaska

Native

people and to develop educational practices that appropriately

incorporate Indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing

into the formal education

system. The initiatives in Table 1 below constituted

the major thrusts of the

AKRSI applied research and educational reform strategy.

Table

1: AKRSI Educational Initiatives

*Indigenous Science Knowledge Base

*Multimedia Cultural Atlas Development

*Native Ways of Knowing

*Elders and Cultural Camps/Academy of Elders

*Village Science Applications/Science Camps and Fairs

*Alaska Native Knowledge Network/Cultural Resources and Web Site

*Mathematics/Science Performance Standards and Assessments

*Alaska Standards for Culturally Responsive Schools

*Native Educator Associations/Leadership Development |

Over a period of ten years, these initiatives served

to strengthen the quality of educational experiences

and consistently

improve

the academic

performance

of students in participating schools throughout

rural Alaska (AKRSI Annual Report 2005). In the course

of implementing the AKRSI initiatives,

we

came to recognize that there is much more to be

gained from further mining the

fertile ground that exists within Indigenous knowledge

systems, as well as at the intersection

of converging knowledge systems and world views.

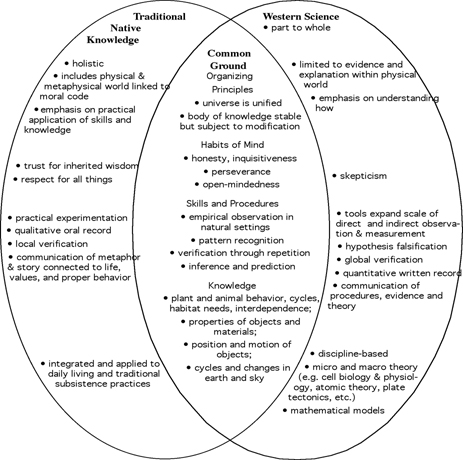

Figure 1 below captures some of the critical elements

that

come into

play

when Indigenous

knowledge systems

and western science traditions are put side-by-side

and nudged together in an effort to develop more

culturally sensitive

interaction.

Figure

1: Indigenous

Knowledge and Western Science Traditions

The implications

for the research and education processes imbedded in the three domains

of knowledge represented

in the overlapping

ovals are

numerous

and

of considerable significance. From an Hegelian

perspective, they could be characterized in

terms of thesis, antithesis

and synthesis—the latter being the ‘common

ground”’ depicted in the diagram.

The list of qualities associated with each

of the three

knowledge domains lend themselves to a comprehensive

research policy agenda in their own right.

In the Handbook for Culturally Responsive

Science Curriculum prepared by AKRSI for Alaska

schools, Sidney Stephens explains the significance

of the various components of this diagram as

follows, “It

has to do with accessing cultural information,

correlating that information with science skills

and concepts, adjusting teaching strategies

to make a place

for such knowledge, and coming to value a new

perspective” (Stephens

2000).

With these considerations in mind, the

Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative served as

a catalyst

to promulgate

reforms

focusing on increasing

the level of connectivity

and complementarities between the formal education

systems and the Indigenous knowledge systems

of the communities

in which

they are

situated. In so

doing, AKRSI attempted to bring the two systems

together in a manner that promotes

a synergistic relationship such that the two

previously disparate systems join to form a

more comprehensive

and holistic system

that can better

serve all

students, not just Alaska Natives, while at

the same time preserving the essential integrity

of each component

of

the larger over-lapping

system.

The implications

of such an approach as it relates to Indigenous

knowledge systems extend far beyond Native

communities

in Alaska,

as indicated

by Battiste in

her comprehensive

literature review on Indigenous Knowledge

and Pedagogy in First Nations Education (Canada):

Indigenous

scholars discovered that Indigenous knowledge

is far more than the binary opposite

of western knowledge.

As

a concept,

Indigenous

knowledge

benchmarks

the limitations of Eurocentric theory --

its methodology, evidence, and conclusions – re-conceptualizes

the resilience and self-reliance of Indigenous

peoples, and underscores the importance of

their own philosophies, heritages, and educational

processes.

Indigenous knowledge fills the ethical and

knowledge gaps in Eurocentric education, research,

and scholarship. By animating the voices and

experiences of the cognitive ‘other’ and

integrating them into the educational process,

it creates a new, balanced centre and a fresh

vantage point from which to analyze Eurocentric

education

and its

pedagogies (Battiste 2002).

When engaging in

the kind of comparative analysis of different

knowledge systems outlined above,

any generalizations

should

be recognized

as indicative and

not definitive, since Indigenous knowledge

systems are diverse themselves, and are constantly

adapting

and changing

in response

to new circumstances.

The qualities identified for both Indigenous

and western systems represent tendencies rather

than

fixed traits,

and thus must

be used cautiously

to avoid overgeneralization (Gutierrez and

Rogoff 2003). At the same time,

it is the

diversity and dynamics of Indigenous societies

and their emergence as a field of study in

their own

right that

we continue to

capitalize upon.

The expansion of the knowledge

base associated with the interaction between western science

and Indigenous

knowledge

systems

has contributed to an

emerging body of scholarly work regarding

the role that local observations and Indigenous

knowledge can play in deepening our understanding

of human and ecological processes, particularly

in reference

to

the experiences

of Indigenous

peoples. Most critical

in that regard for purposes of bringing Indigenous

knowledge out of the shadows in Alaska was

the seminal scholarly

work of Angayuqaq

Oscar

Kawagley,

whose

research revolutionized our understanding

of the role of Indigenous world views and ways

of knowing

and their

relevance

to contemporary

matters

(Kawagley 1995).

As the first Yupiaq to receive a PhD, his

insights opened the door for Indigenous perspectives

to take on new life

as a lens

through

which to

better understand

the world around us. The Alaska Native organizations

and personnel associated with the Alaska

Rural Systemic Initiative,

including

Oscar Kawagley,

played a pivotal role in developing the conceptual

and political underpinnings on which a new

PhD Program in

Indigenous Studies

has been developed

at the University

of Alaska Fairbanks.

The Alaska Federation

of Natives urged the development of advanced

graduate studies

addressing Indigenous

concerns with a formal

resolution adopted

in 2004. Over the next two years we assembled

a list of over

100 Alaska Native

people with master degrees who expressed

an interest in pursuing a PhD. Drawing upon

the

inspiration

and success of the Maori

people in

New Zealand

in preparing

over 500 Maori PhD’s over a five year

period, we acquired planning funds from the

Andrew W. Mellon

Foundation and in the fall of 2007 we brought

together 55 Alaska Natives with PhD aspirations

for an Indigenous

PhD Planning Workshop.

Out of this workshop we were able to identify

the areas of interest around which a new

PhD program

could be built, as well as the support structure

and

delivery system that would be needed to implement

the program. The five areas of emphasis that

were identified were Indigenous education,

languages,

research,

leadership and knowledge systems. The program

makeup was then developed and is now undergoing

review

at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

RESEARCH

AND POLICY STRATEGY

The new PhD Program in

Indigenous Studies will integrate the tools and approaches of

the natural

and social

sciences in

a cross-cultural

and

interdisciplinary framework for analysis

to better understand the emerging dynamic

between

Indigenous knowledge systems, western science

and higher education. We will

focus on the

interface between Indigenous knowledge

and science

on an international scale, with opportunities

for collaboration among Indigenous

peoples from throughout

the circumpolar region. It will also draw

and build upon

past and current initiatives that seek

to utilize Indigenous knowledge

to

strengthen

the curriculum and

pedagogical practices in K-16 education.

With

numerous research initiatives currently in various stages of development

and implementation

around the

circumpolar region, there

is an unprecedented

window of opportunity to open new channels

of communication

between scientists, policy makers and

Indigenous communities, particularly

as they relate

to those research activities that are

of the most consequence to Indigenous peoples

(e.g., effects of climate change, environmental

degradation, contaminants and subsistence

resources,

health and

nutrition, bio/cultural diversity,

Arctic

observation networks, natural resource

management, economic development, resilience

and adaptation,

community viability,

cultural sustainability,

language and

education).

To the extent that there

are competing bodies of knowledge (Indigenous and western)

that

have bearing

on a comprehensive

understanding

of particular research initiatives

associated with Indigenous-related themes, we propose

to offer

opportunities for Indigenous PhD candidates

to be embedded with on-going

research initiatives to contribute

to and learn from the research process.

In addition

to conducting research on the inner

dynamics of Indigenous knowledge systems, the

PhD students

will also be

examining the interplay

between Indigenous

and western knowledge systems, particularly

as it relates to scientific processes

of knowledge construction and utilization.

RELATED

RESOURCES AND INITIATIVES

In January, 2005, the University of

Alaska Fairbanks organized an international

Indigenous Knowledge

Systems Research

Colloquium which

was held at

the University of British Columbia,

bringing

together a representative group

of Indigenous

scholars from the U.S., Canada and

New Zealand “to identify salient

issues and map out a research strategy

and agenda to extend our current

understanding

of the processes that occur within

and at the intersection of diverse

world views and knowledge systems”.

A second gathering of Indigenous

scholars took place in March, 2005

focusing on the theme of “Native

Pedagogy, Power, and Place: Strengthening

Mathematics and Science Education

through Indigenous

Knowledge and Ways of Knowing”.

In Table 2 below is a list of research

topics identified

by the participants in these two

events as warranting further

elucidation as they relate to our

understanding of the role of Indigenous

knowledge systems

in contemporary research and education

contexts.

Table 2: Research Topics

Identified by Indigenous Scholars

from the U.S.,

Canada

and New Zealand

| Native Ways of Knowing |

Indigenous Language Learning |

| Culture, Identity and Cognition |

Ethno-mathematics |

| Place-based Learning/Sense of Place |

Oral Tradition/Story Telling & Metaphor |

| Indigenous Epistemologies |

Disciplinary Structures in Education |

| Indigenizing Research Methods |

Cultural Systems and Complexity Theory |

| Cross-generational Learning |

Ceremonies/Rites of Passage |

| Culturally Responsive Pedagogy |

Technologically Mediated Learning |

| Native Science/Sense Making |

Cultural & Intellectual Property Rights |

Drawing on the seminal work of

the distinguished scholars who

participated

in these meetings,

the research agenda

outlined above is intended

to advance our understanding

of the existing knowledge base associated

with Indigenous

knowledge systems and will contribute

to an emerging international

body of scholarly

work

regarding

the critical role that

local knowledge can

play

in our understanding of global

issues

(Barnhardt and Kawagley 2005).

Alaska Natives have been at the forefront in bringing Indigenous

perspectives

into a variety

of policy

arenas through a

wide range of research and

development initiatives. In the

past few years alone, the U.S.

National

Science Foundation has funded

Alaska projects

incorporating

Indigenous

knowledge in the study of climate

change, the development of Indigenous-based

math curriculum,

a geo-spatial mapping program,

the effects of contaminants on

subsistence

foods,

observations

of the aurora, and alternative

technology for waste disposal.

In addition,

Native

people

have formed

new institutions

of their own

(the Consortium

for Alaska Native Higher Education,

the

Alaska Native Science Commission

and the First Alaskans Institute)

to address

some

of these same issues through

an Indigenous lens. A major limitation

in all these

endeavors, however, has been

the severe lack of Indigenous

people with

advanced degrees

and

research experience

to

bring balance to the Indigenous

knowledge/western science research

enterprise.

One of the long-term

purposes of the current initiative

is

to develop

a

sustainable research infrastructure

that makes

effective

use

of the rich

cultural and

natural environments of Indigenous

peoples

to implement an array of intensive

and comparative research initiatives,

with

partnerships and

collaborations

in Indigenous communities across

the U.S.

and around

the circumpolar world. These

initiatives are intended

to bring together the resources

of Indigenous-serving institutions

and

the communities they

serve to forge new configurations

and

collaborations that

break through the limitations

associated with conventional

paradigms of

scientific research.

Alaska, along

with each of the other

participating Indigenous regions,

provides a natural laboratory

in which Indigenous graduate

students

and

scholars can get first-hand experience

integrating the study of Indigenous

knowledge systems and western

science. The timing of this initiative

is particularly significant as

it

provides a pulse

of activity that capitalizes

on new Indigenous-oriented

academic

offerings

that are emerging in at least

thirty-five institutions around

the

world (Alaska Native Knowledge

Network 2007).

While the University

of Alaska Fairbanks has had a

dismal track

record of

graduating only

four Alaska

Natives with

a PhD over

its entire

90-year history,

there

is now a strong push, due in

large part to the initiative

of Alaska

Native students

and leaders,

to bring resources

to bear

on the

issue. This includes

drawing upon programs and institutions

from

around the world to provide students

with an opportunity

to

access

expertise

from a

variety of

Indigenous settings,

as well as to identify Indigenous

scholars to serve as a member

of their graduate

advisory committee

to help

guide their research

in

ways that

foster cross-disciplinary

collaboration and comparative

analysis.

At the same time, students

from partner institutions engaged

in related research

will be eligible

to participate in

UAF-sponsored courses

and research initiatives

with a comparable goal of promoting

scholarly cross-fertilization

and synergy. Video

and audio conferencing and Internet-based

technologies

will be utilized

to support an array of course

offerings and

joint seminars on topics of interest

to a cross-institutional audience.

Such shared

course

offerings

linking faculty

and students across multiple

institutions have already been

piloted and the

infrastructure is

in place to

expand to the

program areas

outlined above.

Each partner institution will

bring a unique perspective to

the research

initiatives

that will serve to inform and

expand the

capacity

of the overall effort. Close

attention will also be given

to addressing

issues

associated with

ethical and

responsible conduct in research

across cultures and nations,

employing the ‘Mataatua

Declaration on Cultural and Intellectual

Property Rights of Indigenous

People,” “Principles

for the Conduct of Research in

the Arctic’ and the ‘Guidelines

for Respecting Cultural Knowledge’ (Alaska

Native Knowledge Network 2001).

CIRCUMPOLAR INDIGENOUS PHD NETWORK

The University of the Arctic

(UArctic) is a cooperative

network of universities,

colleges,

and other

organizations committed

to higher

education and research

in the North. Members share

resources, facilities, and expertise to

build postsecondary education

programs that

are relevant

and accessible to

northern students. The

overall goal is “to create

a strong, sustainable circumpolar

region by empowering northerners

and northern communities through

education and shared

knowledge” (Kullerud

2005). Within the framework

of the University

of the Arctic there

exist numerous

networks, programs and services

directed toward this goal,

including three PhD networks

and

the International PhD School

for the Study of Arctic Societies,

whose objectives

are as follows:

- to promote the study of Arctic societies in the fields of history,

culture and language;

- to explore new research trends in those fields and to develop coordinated

and collaborative post-graduate teaching;

- to stimulate international networking and synergy between participating

scientific institutions to foster partnerships between

Arctic societies and participating scientific institutions; and,

- to encourage participation of and knowledge sharing with Arctic communities

in its activities, so as

to bring more students from Arctic societies to register at the Ph.D. level (http://www.hum.ku.dk/ipssas/about.html).

With the UArctic infrastructure already in place

across the circumpolar region,

it will serve as a close collaborator,

particularly as

it relates to support

for Indigenous contributions

to circumpolar education, research

and policy efforts. The potential

of UArctic in this regard was noted

by the Arctic

Human Development Report:

Many

Indigenous organizations see the potential of the

University of the

Arctic as an institution

in

which they

may positively

influence northern research

and education. The opportunity

to shape and develop the

curriculum exists,

as well as

the possibilities

for inclusion

of traditional

knowledge

holders

in teaching. This possibility

would

be a major shift from professionalized

faculty

to a more

open classroom,

which

respects different

forms and authority

of knowing and teaching

(Arctic Council

2004).

The University or

Alaska Fairbanks will help actualize

this potential

through

the formation

of an Indigenous

PhD Thematic

Network under

the auspices

of the UArctic.

The international partnerships

associated with this

endeavor are essential

to its success, particularly

as it relates

to gaining a deeper understanding

of the relationship between

Indigenous knowledge

systems

and western

science. The primary

benefits of such collaboration

on

research related to

Indigenous

knowledge systems are

the opportunities for

scholars

and graduate students

to

engage in

cross-cultural

comparison and analysis

of data from diverse

Indigenous settings to

delineate what is particular

to a given

situation

vs. what

is generalizable

across Indigenous populations

and beyond.

There are

also considerable economies

of scale and synergistic

benefits to be gained

from such collaborations,

since

many

of the Indigenous

populations are relatively

small in number

and thus

are seldom able to engage

in

large-scale research

endeavors on their own.

CONCLUSION

The success of this endeavor

will be determined

by the extent to

which Indigenous

people

continue to

provide leadership

and guidance such

that we can forge

a reciprocal relationship

that has relevance

and meaning in

the local

Indigenous contexts,

as well

as in the

broader

social,

political and educational

arenas involved.

By focusing on an

agenda lead by Indigenous

students and

scholars, with interdisciplinary,

cross-institutional

and cross-cultural research

endeavors, the Indigenous

Studies PhD Program

is well

positioned

to ensure

that the

community,

institutional participants

and the infrastructure

supporting them will

move forward on

a pathway to becoming

self-sufficient and

sustainable well

into the future.

REFERENCES

Alaska Native Knowledge Network (2001) ‘Guidelines for Respecting

Cultural Knowledge’ <http://www.ankn.uaf.edu/standards/knowledge.html> (accessed

24 May 2008)

Alaska Native Knowledge Network (2007) ‘Indigenous Higher Education’ <http://www.ankn.uaf.edu/IEW/ihe.html> (accessed

24 May 2008).

Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative (2005) AKRSI Annual Report (Fairbanks,

AK: Alaska Native Knowledge Network, University of Alaska Fairbanks).

Arctic Council (2004) Arctic Human Development Report (Copenhagen: Arctic

Council).

Barnhardt, R. and Kawagley, A.O. (2005) ‘Indigenous Knowledge Systems

and Alaska Native Ways of Knowing’, Anthropology and Education

Quarterly 36, no.1: 8-23.

Barnhardt, R. (2002) ‘Domestication of the Ivory Tower: Institutional

Adaptation to Cultural Distance’, Anthropology and Education

Quarterly 33, no. 2: 238-249.

Barnhardt, R. and Kawagley, A.O. (1999) ‘Education Indigenous to

Place: Western Science Meets Indigenous Reality’, in G. Smith and

D. Williams (eds) Ecological Education in Action, New York: SUNY Press.

Battiste, M. (2002) ‘Indigenous Knowledge and Pedagogy in First Nations

Education: A Literature Review with Recommendations’, Ottawa: Indian

and Northern Affairs Canada.

Gutierrez, K. D. and Rogoff, B. (2003) ‘Cultural Ways of Learning: Individual

Traits or Repertoires of Practice’, Educational Researcher 32, no. 5:

19-25.

Helander-Renvall, E. (2005) ‘Composite Report on Status and Trends

Regarding the Knowledge, Innovations and Practices of Indigenoius and Local

Communities:

Arctic Region’, Geneva: United Nations Environment Program.

James, K. (ed) (2001) ‘Science and Native American Communities’,

Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Kawagley, A. O., Norris-Tull, D. and Norris-Tull, R. (1998) ‘The Indigenous

Worldview of Yupiaq Culture: It's Scientific Nature and Relevance to the Practice

and Teaching of Science’, Journal of Research in Science Teaching 35,

no. 2: 133-144.

Kawagley, O. (1995) ‘A Yupiaq World View: A Pathway to Ecology and Spirit’,

Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press.

Kullerud, L. (2005) ‘UArctic Strategic Plan’, Copenhagen: University

of the Arctic.

Krupnik, I. and Jolly, D. (eds.) (2001) ‘The Earth is Faster

Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change’, Fairbanks, AK: Arctic Research

Consortium of the U.S..

Pfirman, S., Bell, R., Turrin, M., & Mare, P. (2004) ‘Bridging

the Poles: Education Linked with Research’, Washington, D.C.: National Science

Foundation, Office of Polar Programs.

Stephens, S. (2000) ‘Handbook for Culturally Responsive Science

Curriculum’,

Fairbanks, AK: Alaska Native Knowledge Network, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

|