|

Alaskan Eskimo Education:

A Film Analysis of Cultural

Confrontation in the Schools

2/Eskimos and White men on the Kuskokwim

ESKIMOS

AND THE RUSSIAN FUR TRADERS

My search into the history of the Kuskokwim River

Eskimos has been directed toward understanding the continuity that is so

essential to the development

of any people. In this approach of ethnography and history I share the

view that education is a continuing process-out of the past, through the present

and into the future. Hence lifeways and sequences of acculturation seem

the

place to start in considering education for the Native American.

The nature

of White contact with Eskimos, or other Native people, holds important clues

to education and acculturation. School is a major acculturative

experience

where Native children, or any children, learn to adjust and cope with

the imposing world. For Eskimos, or Indians, Afro-Americans or Puerto Ricans,

wherever an

ethnic minority confronts a significantly different majority, this movement

away from ethnic self is an experience that either can give essential

cultural

perspective or can assimilate the child into ineffectual oblivion. Blindness

to Native history and insensitivity to Native self cut a deep chasm between

the White teacher and his Eskimo students, a space that education too

often fails to cross. This account of White-Eskimo relationships, past and

present,

is a description of this gulf that for two centuries has separated White

men from Eskimos.

I am concerned specifically with the Eskimos living

on the waterways of the Kuskokwim River in West Central Alaska. The material

is based

on my

experiences

on the Kuskokwim in the spring of 1969 and on four books that represent

source accounts of this isolated Eskimo environment. Early history

has been drawn

from Lieutenant Zagoskin’s Travels in Russian America, 1842-1844 and from Wendell H. Oswalt’s analysis of the chronicles of the

Moravians in the region, Mission of Change in Alaska, supplemented

by a missionary’s

personal account, Anna B. Schwalbe’s Dayspring on the Kuskokwim.

For contemporary ethnography I have drawn from Oswalt’s Napaskiak:

An Alaskan Eskimo Community, a detailed study of a Kuskokwim village

distinctly comparable

to those in which I worked. This range of observation-Russian trader,

Moravian missionaries, a modern ethnographer, and finally the contemporary

state,

mission, and BIA school personnel with whom I talked-gives us a view

of Eskimos as seen through White eyes.

Prehistory of the Kuskokwim is

barely known, though archeological surveys show contemporary villages

were lived in before the first exploring

White men. For

hundreds of years Yuk-speaking Eskimo have lived in the tundra of

the Kuskokwim Basin, fishing for salmon, gathering berries, hunting moose,

bear, deer,

and small game for food, sharing both dialect and culture with the

Eskimos in the

southern reaches of the Yukon. Both groups are surprisingly similar

to the traditional maritime Eskimos living northward along the Bering

Sea.

Though

the Yuk dialect would not be understood in Kotzebue and Nome, the

music, drumming, and dancing are essentially the same. Despite centuries in

the Alaskan interior,

the Kuskokwim people are still ocean-oriented, with a strong relation

to the sea a hundred miles westward. Seal oil and meat are still

the “soul

foods,” and

mukluks are made from seal and walrus skins. Until a decade

ago they hunted from traditional walrus skin kayaks, and two decades

ago they

lived in sod

houses similar to dwellings still used along the coast. Their courage,

laughter, and philosophy-and their tenacious skill with outboard

motors and snowmobiles-are

typically Eskimo.

Travelers, explorers, and more recently anthropologists

have consistently admired the resourcefulness and survival intelligence

of the Eskimos.

Their uniqueness

built no great architecture; for most traditional Eskimo housing,

as seen in White men’s eyes, appeared temporary. Building

materials were scarce on the coast and tundra. Though life was

migratory in

the search for food,

with dispersed hunting camps as well as villages, the character

of life was social. The wealth of the Eskimo cannot be found in

material

culture; rather

the richness was represented by courageous and skilled performance,

intense self-respect and self-determination. Accounts of Eskimo

culture throughout

the Arctic all tell of severe limitations of life that we today

call extreme deprivation. Out of severe limitation and struggle

for survival

the Eskimo

personality was cast and a ceremonial culture was created.

The peoples

of the world have always faced ecological challenges of survival-

heat, cold, extremes of moisture and aridity. Out

of such

circumstances

were created lifeways of hunting, gathering, fishing, or farming.

Values of competition

and cooperation, patterns of families and communities, and political,

moral, and religious systems were created. When all these climes

and circumstances

are viewed, it is not clear that men form similar attitudes in

response to similar environments. Writers like Ruth Benedict

in dealing with

personality point out that culture is also arbitrary, a result

of choices of how

to deal

with environmental circumstances. Thus, the Athabascan Indians

a hundred miles further inland faced an environment similar to

that

of the river

Eskimos, but

these two peoples have very distinct life styles and attitudes.

The Kuskokwim people from earliest description have sustained

a communal

village style

of culture. They could have broken down into extended family

groups and lived in smaller bands as did the Athabascans, but they chose

to be together.

From

the earliest observation their life has been village-centered,

social, and family-involved. This characteristic is as true today

as it was

150 years

ago.

What was it like on the Kuskokwim in the 1840s?

And what is it like today? How has White judgment of Eskimo life changed in

the intervening

130

years? The observations of Lieutenant Zagoskin give us a baseline

from which to

work forward (Michael 1967).

Zagoskin observed that the Eskimos

chose a social structure with maximum equality and minimal authority. Though

they may

have

appeared as “children” in

Western eyes, they were recognized as considerate with a

highly socialized sense of individual well-being. Interpersonal

concern

was cited many times

in Zagoskins writings. Overt criticism or ordering other

people to do service was avoided. Oswalt observed instances

of this

nature in the 1950s. So, in

the face of extreme circumstances of limitation and sometimes

starvation, the Kuskokwim people built a culture of remarkable

sensitivity. Among

other primitive” people who are credited with a high

degree of interpersonal refinement, we are reminded of Theodora

Kroeber’s story of Ishi, and

of John Marshall’s films and Elizabeth Marshall Thomas’s

writings on the Kalahari Bushmen.

The center of all ceremony,

communication, and general education in the old days was

the kashgee or kazhim, a spacious earth-covered

structure

which

was the men’s communal house.1 Describing

a twenty-four-day period in an Eskimo community, Zagoskin

starts and finishes

his account in this central

dwelling. The kashgee could be compared to the Southwest

kiva, where in archeological times a whole pueblo

might gather for special ceremony (for example, the Great

Kiva in the ruins at Aztec, New Mexico). In some villages

the kashgee could accommodate 500 people, indeed

all the villagers and guests from other communities.

This

focal point of sociability and ceremony was also a ceremonial

bathhouse for the men. Cleanliness may have been a basic

purpose, but more, the

bath was a time for men to socialize and to test their endurance

for places

of prestige. As if in balance with enduring bitter cold,

the kashgee was a place

to bear

unendurable heat. Men of the village gathered round a snapping

sprucewood bonfire with choking smoke that filled the kashgee before finding

its way out

the smoke hole. The room had tiers of benches, and while

adolescents crouched on the floor, the strongest men suffered

the heat

from the highest tier

where the smoke and heat were intense. Wads of shredded wood

would be held to the

mouth to filter out the smoke, and the endurance bath would

proceed till, one by one, the men would crawl out or be carried

out into

the snow.

The kashgee was chiefly a dwelling place

for men and boys, and here the mystique of the culture was passed on. Here

travelers from afar

were

given lodging,

food, and entertainment. Home was described as elsewhere,

in other smaller earth-covered dwellings. Men might bathe,

visit,

and doze

till past midnight,

and then slip away to join their wives or keep clandestine

rendezvous.

The organizing process of the kashgee continued up to the

proselytizing of the

Moravians, which succeeded finally in undermining its function

forever.

Russian enterprise had begun in the Aleutians and

Kodiak Island in 1741. In the following century Russia established

the fur

trade in

Alaska and

finally as far south as California. The first Russian

explorers, fur traders and

imperialists,

were familiar with the steppes and forested wilderness

of Siberia where standards of life were not so different

from

those of

the Eskimos. For sheer survival

the Russians had to accept many Eskimo standards, foods,

and technology, or perish.

There is little account of

Russian women in the early decades in Alaska, and there was a generous intermingling

and marriage

with

Native women.

By the time

the Russian American Fur Company penetrated the Kuskokwim

in the early 1800s, a large part of the company personnel

was “Creole,” which in the

Alaskan context means Russian mixed with Aleut, Indian,

or Eskimo. The most successful manager was himself

a Creole. Thus, relations with the Eskimos in

this period were far more relaxed for the Russians

than for the Moravian missionaries who came later.

The

Russian traveler, Lieutenant Lavrentiy Alekseyevich

Zagoskin, who came to the Yukon and Kuskokwim on a

tour of inspection

in 1842, found

the Kuskokwim

Eskimos living on the edge of hunger and sometimes

starving, so severe were the long winters. Leaving

marine hunting

grounds, where

some

sea mammals are available year round, may have posed

subsistence problems

for the river

Eskimos. They had come inland because of stable salmon

fishing and had learned

to exist on fish. But salmon fishing techniques were

not so efficient as today.

And what happened if the fishing harvest had been small,

or if for some reason a cache were destroyed, or if

spring were

too

long in

coming? The vast tundra

offered little other food that could support a sedentary

population. Large animals, moose, bear, and caribou

could not be depended

upon; they

ranged

too widely. Caribou herds moved fast and could disappear

in the night, and the

river Eskimos lacked the technology for inland hunting

in winter. Through the long winters and into the spring

when

fish supplies

ran low, there

was hunger

in the river communities. The winter solstice ceremonies

of many northern peoples describe the hardships of

winter hunger.

So

often the legend

is the same, whether

this be the premedieval Santa Lucia ceremony of Sweden

or the winter solstice deer dance of the Pueblo Indians.

The

village

is starving,

the snow too

deep for hunting, stored foods have run low. Then a

miracle saves families from

starvation. In Sweden it is a Viking ship coming across

the waters loaded with food. In Taos Indian pueblo

in New Mexico

it is the

charming of

the deer by

two deer mothers who lure the game to the village.

Much

of Zagoskin’s account is of mutually shared hardship.

The Russian post and the Eskimo villagers together

had difficulty surviving on the limited

game in the area, particularly through the last terrible

weeks of winter, when dried fish supplies were depleted

and travel to hunt for game became ever more

perilous as spring approached and the river ice grew

more rotten. Even today a delayed spring is a lean

time as stores run low. The Kuskokwim posts were

marginal operations, with only limited support from

the Russian American Fur Company whose headquarters

were far off at the mouth of the Yukon. Russian

traders and Eskimos alike had to exist on occasional

birds, rabbits, or other small game, though the Russians

with guns could apparently hunt game that the

Eskimos were unable to bring down either with snares

or bow and arrows. Zagoskin’s

journal describes these days:

April 17th. Murky; occasionally

fine snow; a fresh north by northeast wind until noon;

in the evening

a south

by southeast wind with

light rain squalls.

In the evening one of the returning hunters delighted

us. He and the Tungus

{shamans} had succeeded in shooting two deer and in

capturing three bear cubs; the she-bear had run away.

It is strange

that she decided

to leave

the cubs.

The tundra is almost entirely clear of snow. The dogs

are exhausted and the loaded sled is stuck in an overflowing

draw about 3

miles from the

fort.

The hunter has come for help. Who would refuse a piece

of good meat!

April 18. Murky and a fine snow in the

morning; a gentle west wind. Slightly cloudy in the afternoon,

gentle

north by northeast

wind.

Of the 5 puds {pud, a Russian measure weighing 36.11

pounds} and 35 pounds of deer meat, the men at the

fort were given

2 puds and

12 pounds.

Thus

it came about that we helped those who were supposed

to help us; praise God,

but without a reliable weapon I would have not agreed

to survey the Kuskokwim. . .

In place of fresh fish, which has not been caught since

the 16th, the natives are cooking dressed sealskin

and the bladders,

which

are empty

of fat.

Occasionally someone gets a grouse, someone else a

duck, the lucky ones a goose. All of

this food is given to the children (Michael 1967:257).

There

are accounts of Russian ruthlessness and insensitivity to the

Natives and their ecology. There are stories

of cruelty and

massacres

of Natives

in the Aleutians. But by the time the Russian American

Fur Company penetrated the Kuskokwim, the great wilderness

and

the need of

collaboration with

Indians and Eskimos greatly modified their behavior.

Their dealings with the Kuskokwim

Eskimos were inept but friendly. As stated, they “starved

together” when

hunger stalked the river. The accompanying Orthodox

priests were generally benign and made little inroads

on the ethnic well-being of the Eskimos. Lieutenant

Zagoskin, representing the Czar and the Russian American

Fur Company, laid

down in his report what might be considered the guidelines

of protocol between the traders and the Eskimos.

In

conclusion let me repeat that whether our trade flourishes

or diminishes in this region depends enormously

on the

ability and

good intentions

of the man in charge of the post. The native is very

appreciative of kind

treatment.

He sometimes finds himself in need of certain things

for which he is unable to pay, but no credit is extended.

But

if the

man in charge

handles his

affairs in this way, the take in furs will not cover

his expenses. Similarly his

profit will be small if he plays the gentleman, as

is done, for example, at Fort St.

Michael, and does not allow anyone in his room. Lukin

has always kept

open house; we have often seen a dozen natives in

his little room who will wait

silently for days at a time until he returns from

his work in the woods or at the fish-trap. If guests

arrive

at meal-time,

the piece

of yukola {dried

fish} and the teapot of “colonial” tea

are divided among those present. As he knows

their customs well, he never asks who a visitor

is or

for what purpose he has come (Michael 1967:255).

The

protocol of the Russian American Fur Company was

considerably more formal, but also reflected

the human

necessity for

genuine collaboration with the

Eskimos. The very survival of their enterprise

depended upon this. Zagoskin reports

in his journal the company’s instructions

to Lukin, manager of the post on the Kuskokwim:

In

the four villages nearest to the Khulitna, as

I have designated, inform my friends and acquaintances

that

I wish them to be

toyons {tribal elders,

term brought from Siberia; elders from each village

who were appointed overseers by Russian American

Fur

Company

were

called toyon.} (Michael

1967:332) in

those villages, and to have honor and fame from

God and our beloved Commander-in-Chief. I beg you

to

receive them as

trusted friends,

diligent in the interests

of the Company, with their loyal relations and

close comrades, and to procure medals for them,

and for

them to be loyal

subjects of

our tsar

Nicholas

Pavlovich

(Michael 1967:285).

From the first contact in the

1700s the Russians were involved in educating Native Americans.

The

White man

with his superior

sophistication

readily

assumes the role of teacher to the Native. Zagoskin

was no exception, and he made some

significant observations on the educational effect

of removing Natives from their environment to

a role in

the larger

Russian posts. Zagoskin

observed

that Creoles growing up in the relatively civilized

atmosphere of the posts were not as effective

as those living in

the bush.

One has to admit that in practical

experience all Creoles living in the outlying division far surpass

their fellows

who have

grown up in

the

principal settlements

of our colonies. This is only natural. From the

time he is small, the Creole in the hinterland

is trained

to work

and

by his native

keenness

of wit

and alertness he develops into a bold hunter

who is resourceful in the emergencies

that frequently arise (Michael 1967:262).

This

observation refers to the Creole, but with Native Eskimos the

principle

remains the same. Zagoskin complained that Native

girls who married into the

settlements learned to dance European steps and

adjusted to a life of relative

leisure, but they gave up their Native skills

and ability to work. The ineptness of Native

girls

gone civilized

in the Russian

settlements

was

so disturbing

that in 1837 a women’s training school was founded under the auspices

of the wife of the

commander-in-chief of the colonies. The goal

of the school was “to provide

well-brought-up and industrious housewives for the growing generation of Creoles,”

who must have represented the expanding population

of Russian America. Zagoskin observed,

At present

each pupil learns to sew and to dress birdskins and to make rain-

parkas, to weave various household articles such

as mats and others of grass and various roots-all

things

highly

useful to women who

intend sharing their

husband’s work in their homeland (Michael

1967:301).

This is a far cry from a Home Economics

class today in Bethel High School. In 1837 the

Russians

were

willing to skip European

academics

and elegance

for education to live in the Arctic ecology.

Zagoskin

as a White teacher was critical of the educational attitude of

some of his Russian colleagues.

Commenting

on company employees

who exploited

the credulity of the Eskimos to represent advanced

technology as magic, Zagoskin

says:

In showing them my watch, the compass

needle, the force of gunpowder, etc., I tried as much

as possible

to

acquaint the native with

the structure and

use of these objects. I explained to them that

this is all

the result of the cleverness

of man, and that they too, if they wished, could

learn to do likewise (Michael 1967:108, 292).

Zagoskin

also observed some of the pathos of the shift from subsistence

to trapping for trade

goods

after

watching Upper

Kuskokwim Eskimos

trade within

an hour 164 beaver pelts, 4 otter, 2 deer, and

2 black bear skins for a handful of trinkets.

Each

one covered his head with a blue cloth cap with red piping, and

laid in a

year’s supply of tobacco, beads, flint, and sealskin thongs

for taking deer. . .

The carefree children of the North dressed themselves

up and started to dance.

We must recall that a

beaver pelt is of no value in the eyes of the native. He kills

the heaver

for its

meat,

but only

uses the

hide

as a last resort

to make socks, or thongs for deer nooses. We

must remember that 10 years ago we

found this native with a stone ax, bone needles,

in a cold beaver-skin parka, starting a fire

by rubbing together

two wooden sticks,

and without any practical

domestic utensils. We must not judge too harshly

the

fact

that he sometimes exchanges what is of no use

to himself for something

which

has little

in our eyes. The northern native needs education

as does a child; his education

depends

on us. At the present time his prosperity on

earth depends on the possession of a gun and

10 rows

of potatoes. This

could be

achieved

with comparative

ease (Michael 1967: 269-270). 2

Here White education

began. What did the Eskimo need then for survival, and what does

the Eskimo

need

now? Can we

say today

with any conviction

that

the problems and the solutions are appreciably

different from those the Russian lieutenant analyzed

130 years

ago?

The Russian influence, ending in 1867,

appeared to have effected little change in Kuskokwim culture

in terms

of subsistence,

technology, or

hygiene. The

stability of the Eskimo life style in this period

is partly explained by the survival

balance of fishing. The Russians introduced firearms,

which broadened the survival base, and they introduced

a trading

economy based

on currency in the form of

beaver pelts. Certainly hunting beaver for trade,

trapping for trade goods

rather than for food, tipped the Eskimo’s

ecological relationships and drastically altered

many associations. But apparently these did not

disturb

the balance of the fishing economy. Salmon was

the reason for the Eskimo’s

presence on the Kuskokwim, and even today salmon

remains the ecological hub of survival. This

is in contrast to the experience of inland Eskimos

in the

Hudson Bay region who died away completely after

the Hudson Bay Company lured them away from caribou

hunting to trap for the company; then when the

fur market

collapsed, these Eskimos were technologically

unable to return to caribou hunting, and in a

short time the group perished.

The Russians were

the Eskimos’ first White teachers. Significantly

they had made the Kuskokwim Eskimos aware of

the surrounding White world with its

exotic wares, concepts of improved living conditions,

and an image of Christianity. The Russian priests

taught the Natives the litany of the Russian

Orthodox religion

and some aspects of Christian morality. They

were permissive teachers; the few demands they

made on the Eskimos were essentially ceremonial-that

they

cross themselves, learn the chants, and attend

to the ornate Orthodox calendar. In a real sense

the Russian Orthodox missions turned ceremony

over to the Eskimos,

for so rarely were priests able to visit the

villages. When the Russian empire withdrew Orthodoxy

remained, mystically absorbed into Eskimo ceremony.

THE

COMING

OF THE MORAVIANS

The sale of Alaska to the United

States only briefly interrupted the fur trade, since an American

receiving

company took

over the crumbling

assets

of the Russian

American Fur Company. But it was almost two decades

before a new and different American influence

entered the area:

missionaries from the

Moravian Church,

an Evangelical Protestant sect which had been

founded in Bethelem, Pennsylvania, in the early

eighteenth

century and which had

long

been active in the

mission field among American Indians.

Sheldon

Jackson, a Presbyterian educator and reformer, first drew the

attention of the Moravians

to the

Kuskokwim as a

new field

worthy of

their zeal.

Traveling in Alaska in the l870s, Jackson became

greatly concerned about conditions

of Eskimo life, by poverty and squalor and what

he considered moral degeneration, which he attributed

to unwholesome

White influences.

He felt that the

encroaching White culture had already destroyed

the

traditional Eskimo culture and

broken down their economy, and that only a major

effort of wholesome White influences,

namely Christian missionaries, could save them

from depravity. It was in direct

response to his lectures in the United States

that the Moravians decided to go to the Kuskokwim

(Oswalt

1963a:16-17).

Yet when we compare Jackson’s

account to that of Zagoskin forty years earlier,

it seems not unlikely that a large part of Jackson’s

reaction was one of extreme culture shock at

many normal elements of Eskimo life style-a

style that White sensibilities still find

upsetting today. The poverty and squalor were

reported

in almost the same terms by Zagoskin. Hunger

has always

stalked man in the Arctic. Housing was primevally

crowded, and practices of hygiene were (and still

are) ecologically restricted.

The Moravian mission

came to the Arctic a century later than the Russians.

The westward movement

of the United

States

had come much

closer to

Alaska in that century. Alaska was an extension

of the American frontier and

the vigorous

expansion of western progress. The Moravians

came as teachers from the United Stares of the

1880s,

representing

the good

life of technology

and material

achievement. Despite early frontier hardships,

the Moravians were to stay and bring modern White

values

to the Eskimos.

It was a

double drive,

to

bring not

only Protestant Christianity but the material

values, hygiene, and educational fulfillment

of White America

as well.

No doubt the missionaries carried

in their mind’s eye the orderly image

of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, the spiritual home

of their denomination. What had been in the Russians’ image?

The vast wastes of Siberia? The primitive peasant communities

everywhere in eighteenth-century Russia? There was

far less discrepancy in conditions between Alaska

and Russia than between Alaska and the eastern seaboard of the

United States a century later. Reasonably the

expectations of the Moravians were far different

from those of the Russians, who were there to get fur and survive

as best they could. The Moravians came

as teachers and missionaries to bring “the

good life” as well

as “the good news” that the Eskimos

could enter heaven and be freed from their pagan,

poverty-stricken life; they saw it as their calling

to endure

their hardships until American modernity would

come and ease their lot and bring further enlightenment

to the river Eskimos.

As teachers they came as

outlanders and predictably would return where

they came from. The Eskimos

had come in

such a dim past

that they believed

they

had always been there. The message of the missionaries

and other White educators might be stated: “Yes,

you have always been here in this dreadful place,

but through our teachings you will be liberated

to leave.” It is creditable

to the zeal of the Moravians that some of them

did not leave but stayed on till death came by

accident or old age. Nevertheless the Kuskokwim

was a place

to leave, because of the hardships, the isolation,

the intense cold, the summer mosquitoes, and

the often revolting life of the Natives, including

their Christian

converts. This revulsion was no particular fault

of the missionaries. They were as a group generous

and dedicated, but they were White with customs,

values,

and styles that made the aboriginal ways of Eskimos

unacceptable and shocking. And of course, while

many stayed on, others left within a couple of

years for

medical reasons, for culture shock, or for comfort

in their retirement. So despite the continuous

residence of many of the mission’s founders,

the pattern throughout the mission history was

the same as today: to endure with

self-sacrificing zeal, but eventually to go home

again.

Epigramatically, the very ecology

and life style that challenged missionary zeal also quietly

became a measure

of their

fulfillment that ordered

life in the states did not offer. Individually,

I am sure, the Arctic and the

Eskimo

entered the missionaries’ psyche, but their

Christian programming appeared to keep these

involvements out of their teaching. In appreciation

of this

problem, White teachers today on the Kuskokwim

also get deeply involved in the Arctic drama,

but as with the Moravians, the drama that lures

White teachers

to lonely Alaska today only rarely finds its

way into the ordered White classrooms.

This brief

writing cannot fathom the motivations of Christian

missionaries, and members of the

White race

in general,

that send us to the farthest

corners of the world to sell our way of life.

Humanly we seem to be searching for

a challenge our home place does not offer, and

many of us find our fulfillment as outlanders

in strange

places.

The

compulsion

may be

both aggression

and, on the part of religious missionaries, guilt.

Christianity is not the only

creed of civilization, but historically Christianity

has been territorial. By fire and sword the lands

must be wrested

from

the colored infidels

by the

White crusaders. Dr. Albert Schweitzer, certainly

one of the inspired Western missionaries, could

not accept

his

precocious success as

a young professor

at the University of Strasbourg, saying, “It

struck me as incomprehensible that I should be

allowed to lead such a happy life, while I saw

so many people

around me wrestling with care and suffering” (Schweitzer

1949:84). He tried absolving his guilt in various

ways and finally determined to practice

medicine in the most difficult and primitive

locale in the world, in search of his own salvation;

at any rate, Lambarene deeply fulfilled Schweitzer’s

need.

Moravian teachers on the Kuskokwim

today seem equally fulfilled, friendly, warm people.

For

the Moravians,

of course, the

challenge was to save

Eskimo souls in the rigors of the Arctic. With

exemplary ethnocentrism Christians

are prone to feel that other peoples have no

concept of the soul-indeed that the soul is lost

except

through Christian

salvation. This

suggests that they

approach the Eskimo to be converted with the

preconceived image of an empty vessel to be filled.

The student

in the classroom

waiting to learn

is perceived

in the same way. Again, out of appreciation of

the cultural stranger, it is questionable whether

the

White teachers

in

Alaskan schools

today have

an appreciably

greater respect for cultural difference than

did the early pioneer educators of the 1880s.

What

is this

image that

is so significant

to the goals

and content of White education for Eskimos or

Native people most anywhere? We suspect the

image is drawn with the same chalk whether teachers

come to preach Christianity or simply to represent

what they

feel to

be a superior

society.

Moravian writings describe vividly

their first reactions to the Eskimos. Hartmann and

Weinland

were the Moravians

who first

surveyed

the Kuskokwim

area in 1884

for a possible mission sire. Oswalt summarizes

their reports:

They were appalled by what they

saw. They regarded the living conditions as filthy beyond description,

and the

Eskimos

were far more backward

than they

had anticipated. Two things, however, impressed

them beyond all else: the mosquitoes and the

lice (Oswalt

1963a:19).

After being in the field for nearly

two years, Weinland was still very displeased with the Eskimo

behavior:

Taken as a class, the Yuutes are

decidedly phlegmatic in temperament. They are content to take

things

as they come,

be it threatened

starvation or

overabundance, be it intense cold or drenching

rain, all seem to be regarded as so many

phases of life which must necessarily be experienced, & to

try to alleviate which they hardly dream. Life

is to them one prolonged series of sufferings;

such

as but few could endure, & yet suicide is

unheard of among them. They are deeply rooted

in their habits & manner of living, & it

is a difficult matter to get them to adopt even

the most striking & most evidently necessary

changes. White men have been living in their

midst for half a century, and yet today their

mode of living is rude, uncivilized, filthy.

Taken as a class,

the Yuutes are dishonest, thievish, and their

word cannot be trusted. In trade, they will rarely

acknowledge that they are in debt, and it seems

to be their

highest ambition to defraud the traders. They

cannot be called robbers, for they are too cowardly

to steal any large articles. But pilfering of

small articles

under circumstances where detection is difficult,

this is common, & to

be found out appears to be a greater disgrace

than the wrong doing itself (Oswalt 1963a:28).

This

observation is a brilliant summing up of Native

pragmatism on the one hand and the White

man’s ethnocentric concepts of morality

on the other. Weinland reflects his feelings

in detail in a letter describing the indigenous

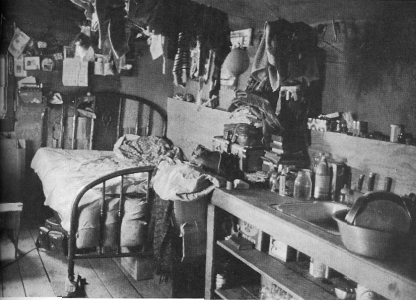

half-submerged sod house called a barabarrah,

that is built with a tunneled

entrance to keep out the cold:

Through this tunnel

I must crawl every time I go to see my two patients.

. .

Emerging from the tunnel, through which you have

squeezed past several dogs, groped in the darkness,

and raised

a curtain of dirty matting,

you find yourself

in the barabarrah, or house proper. It is about

twelve feet square, with matting lying on the

ground around

the four

sides.

When

I entered this

evening, it

was dark, and calling for lights, a sight was

disclosed, which, alas, is but too common. In

this small space,

dirty, filthy,

and filled

with an

indescribable stench, were fifteen persons, men

women and children, besides several dogs.

The space in the centre of the barabarrah is

always occupied by buckets of water, dishes of

food, slop

pails, etc.

(Oswalt 1963a:29).

I sympathize with Weinland’s

reactions. Indeed it was an extreme step from

Pennsylvania to the conditions of the Kuskokwim.

For most of us, Christian

or not, thrown in this same circumstance, our

reactions probably would be the same. Quite aside

from moral considerations, White value judgments

were then

and still are very inflexible toward what we

consider hygiene. Filth, overcrowding, stench,

and darkness are bound to shock our sensibilities.

The culture shock

of the Moravians certainly must have blurred

the Eskimo personality. Culture shock is blinding

and negative and must have made it difficult

for the missionary

teachers to work with the positive elements of

Eskimo life. The missionaries intended to save

the Eskimo from his sufferings and despair, even

though as

Weinland was sensitive enough to note, the conditions

he found shocking were of little importance to

the Eskimos.

Missionary sentiment is expressed

poetically in The Moravian published in June 1895 (Schwalbe

1951:29):

The Cry of the Alaskan Children

Far

from the islands of Bering’s dark sea

Comes the sad cry of the children to me,

Help, in the name of the Father of all;

Give to us, starving in body and soul.

Out of our misery gather us in,

Give us a refuge from suffering and sin.

Mrs. John Kilbuck, one

of the original group of missionaries, wrote to a New Bedford

paper

defending

the value

of the mission work

and inviting

any

doubters

to come and see the results, saying, “It

requires only about six months of proper Christian

influence to change the listless animal-like

expression

into one of intelligence” (Schwalbe 1951:30).

This speaks not only of the academic accomplishment

of the mission school but also of the aptness

of the Eskimo student to be able in only six

months to communicate sensibly

with his Christian teachers in ways that allowed

them to appreciate that the Eskimos were indeed

intelligent and capable of human feelings.

Anna

Buxbaum Schwalbe, missionary from 1909 to 1948

and author of the Moravian chronicle Dayspring

on

the Kuskokwim,

observed

as did

Weinland

that the

misery of the Eskimo was primarily in the eyes

and hearts of the missionaries-which was a major

problem in conversion.

In the earliest years high

moral standards were entirely lacking. The

people seemed to fail to

see the enormity

of it all, saying

that such

were their

customs and that it had never marred their

happiness. Little girls of nine or ten were

made prostitutes by their parents. Polygamy

was practiced. Women thought nothing of leaving their

husbands and

vice versa. Men

travelling from

village to village

exchanged wives. Cruelty was common. Nothing

was thought of the killing off of unwanted

infants, especially girl babies. The

missionaries knew of one old woman believed

to be a

witch or

shaman who was

said

to have

caused

the

death of several children. She was clubbed

to death,

her joints severed, and she was burned in

oil. The dead were

wrapped in

skins or doubled

up into a

rude coffin. Sometimes they were placed on

scaffolds out of the reach of dogs. More often they were

placed on the

tundra where

they were

devoured by the hungry

beasts (Schwalbe 1951:30).

Most of these observations

are ethnographically sound and similar instances

noted by less partisan

reporters.

But

the missionaries

were unable

to see the reasons and the functions of the manners

and morals that so shocked

them, nor

had they the historical perspective to see an

affinity between the witch incident described

above and

the pillorying, burning,

and drowning

of

witches

in their

own not too distant European and New England

Protestant background.

The Russian traders had

to survive by ecological cooperation with the Eskimos. The early

Moravian

missionaries also

had to master

many of

the Eskimos’ skills

and help one another through the long winters.

On many levels life may have been even harder

for them than for the Russians, for the Moravians

came far

less prepared to deal with Arctic life and Native

values. But despite essential survival interaction

with the Eskimos, cultural difference drew the

curtain

so completely over Eskimo personality that even

when circumstance did present the humanism of

the Eskimo, and the missionaries acknowledged

these breakthroughs,

still they were unable to incorporate these insights

into their programming.

A number of missionary

wives bore children iii Bethel, and there was

concern as to whether this

was a good

addition to the missionaries’ work.

Of one

mission family Mrs. Schwalbe writes:

“Christie,” the eldest,

ran in and out of the native cabins, speaking the Eskimo language,

accepting their friendship and rejoicing greatly over

the small boats and the bows and arrows that

the old men carved for him and the little boots and other fur

garments that the grateful mothers and grandmothers

offered in token of their love for the small

Cossayagak (little white boy). More often than not, although

the mothers on the field view with the greatest

concern the possibility of the contaminative

influences, children have to be a very real blessing. “Now

you are really one of us” is the expression

frequently voiced by the native women when

the first-born comes to the missionary mother (Schwalbe 1951:74).

We

see that Eskimos love children after all and pay homage to the

first born, which is in contradiction

to earlier

missionary observations

on the callousness

of Eskimo parents about children.

Equally significant,

as Schwalbe (1951:87) notes, is the fact that “Christie,” born

on the Kuskokwim, in spite of his missionary

parents, “ran in and out

of the native cabins, speaking the Eskimo language,

accepting their friendship. . . ” Apparently Eskimo domestic

life that still shocks White teachers today did

not bother Christie, even as a missionary child.

Death

came to the missionary children too. In 1901 a whooping cough

epidemic carried away many

children,

including

the

infant son of

a missionary.

The natives, full of sorrow and expressing

their grief, came to the Weinlick home. It is

at such times that one comes to realize fully

the sympathetic heart of the Eskimo. Some have

pronounced

them an apathetic,

stoical

race of people.

It

may be that what seems to be a mask of indifference,

merely covers a kind

of timidity, a hesitancy to show a flood of

emotion that once opened could not

be controlled. Certain it is that the heart

is overflowing with love. Death has been such a

frequent visitor,

that, schooling themselves against his

coming, they have learned a calmness that few

of us achieve. They do not say, “We

shall die” but rather “We shall cease

living,” or “We

shall go from this earth” (Schwalbe 1951:87).

This

is an important observation about Eskimo compassion

gathered from a circumstance that

happened in the

early decades of the

Moravian mission.

Reasonably

this describes Eskimos prior to extensive Christian

teaching. Unless we support

the missionary thesis of nigh-instant personality

change experienced by Christian conversion, I

feel this early

record of Eskimo

sentiment offers

a positive

foundation for describing the Eskimo personality

as it was before the Moravians opened their first

boarding

school in

Bethel.

MORAVIAN INVOLVEMENT IN

THE LIFE ON THE ESKIMOS

The missionaries found

the river Eskimos living in organized communities

with

a fulfilling

ceremonial

life expressed

in the

potlatches or

giveaway ceremonies3 and

other communal activities surrounding the kashgee.

As earlier described,

this communal male

dwelling was a

center where

the whole village could assemble. For the Eskimo

man, day began and ended in

the kashgee. It was the hub of all enterprise.

For the boys it was also the school

and the portal which led into manhood. The missionaries

first witnessed the richness of Eskimo culture

in the kashgee, and it was within

the kashgee that the missionaries first preached

their gospel.

Weinland described a

ceremony he and Kilbuck visited in Napaskiak

in 1886, probably a “Boys Dance.”

On

entering the kashima, we saw the men hard at

work making masks, & finished

masks standing around everywhere. We were greeted

very cordially, different ones inviting us to

their seats on the benches. . . . Before long

four drums

were brought in, & a practice of the real

ekorushka was held. {Ekorushka is

a Russian-derived term under which the Moravians

lumped most of

the Eskimo

ceremonies.} A young man, masked, & holding

a wood chip in each hand, took his seat on the

floor of the kashima. A young man knelt opposite

him, & back

of this one, stood a woman & young girl.

At a given time one of the drummers opened the

performance by beating time on his drum, while

the masked young

man began some peculiar jirations, which were

imitated by the young man opposite to him, & by

the females standing further back. In a few minutes

the other drums joined in, an old man dictated

a song, & the entire company joined

in singing. Following this came an interlude,

during which the singing ceased, while the; drumming & the

corresponding jirations continued. Thus six

parts were gone through with, the entire performance

lasting about fifteen minutes.

. . . The entire performance was not regarded

as anything serious, for the more ridiculous

it could

be made the

better it was

liked . . . (Oswalt

1963a:59-60).

Two days later they returned for

the actual ceremony. This had not yet begun when the missionaries

arrived, but they

were ushered

into

the men’s house

to wait.

He told us to go to the kashima

meanwhile, where we found some of the natives practicing

their

parts. A

large number

of masks

were

hung around

the kashima, & my

first thought when I entered the place was, “This

looks like a fair.” Four

male performers, wearing large masks of most

wonderful designs, and one female performer,

occupied the stage, & were going through

peculiar jirations, keeping time with the beating

of eight drums, four on each side of the stage.

Soon after our arrival an intermission was taken,

during which the women & children

filed out. This gave me an opportunity to count

them, & I found that one

hundred & twenty people had been in the kashima....

Near

the roof of the kashima hung two representations

of birds, the one of an eagle, the other

of a sea-gull. On

the eagle

stood a stuffed

representation

of a male native & on the seagull that

of a female. Upon inquiry I learned that

these represented

the spirits of deceased natives being borne

upward after

death. The kashima was cold and draughty,

and, as I had wet feet, I began to feel very

uncomfortable

(Oswalt l963a:60-61).

On first experience the

missionaries did not equate religious experience

with the kashgee performances

because they

looked “like a fair” and

because “the more ridiculous it could be

made the better it was liked.” In

their Protestant Christian eyes there could be

no mixing of sacred and profane, of religious

ceremony and entertainment, so they were unimpressed

at any possible

religious significance of the performance. It

was not until later that the Moravians realized

the true significance of the kashgee ceremonies.

A

major function of many gatherings was the giving

and receiving of gifts. The gift-giving ceremonies

described

by the Moravians

appeared sincerely

directed to sharing, despite any social recognition

achieved by the host community and

the gift-giving individuals.

They play it in

this way. They ask the presents of each other. First, the women

asked for what

presents

they

wanted of the

men; then the

men of the

women.

The women came together, got a long stick,

tied strings to it at intervals of about an

inch,

then passed

it around to

each

woman,

who tied something,

anything to the end of one of the strings and

named what she wanted. The leader took particular

note

of what she

said and

the string

she tied to.

When all the women had asked for something

the leaders took the stick to the men

and told them what each string called for and

whom it belonged to. Each man then took off

one or more

of the

strings and

got as nearly

as he

could what

was asked for. When all have their presents

ready they meet, and the women also come together.

As soon as

all have arrived

at the

place of meeting

they begin to sing and dance and present their

gifts, with a dish of something to eat along

with it. If

they are able

they

give more

than

was asked of them; if not,

it is never noticed. When all is over, the

men in like manner ask

presents of the women (Oswalt 1963a:61).

Missionary

accounts written in these early years continue

to describe the splendour and generosity

of the ceremonies.

Considering

how

rude and distasteful

the

missionaries considered the physical level of

Eskimo life, no doubt they were baffled and impressed

by what they first

considered

to

be merry

entertainment to make life more tolerable for

the

Eskimos. Weinland. considering his

first impressions of the kashima programs, made

this observation.

We are unanimous in the opinion

that so far as these different performances themselves are concerned,

there is nothing

immoral in them, but that

much immorality is carried on under cover. It

cannot well be otherwise, where

so many uncivilized

people are herded together (promiscuously).4

Weinland

and the succession of missionaries that followed him certainly

expected to find scenes

of primitive

orgies, and

they must have

been surprised and

relieved at finding lifeways among the Eskimos

as well-ordered and civil as they were.

On first

contact missionaries did not feel the Kuskokwim Eskimos had a

religion, or if they

had, it was being

forgotten. Young

people were

unable

to discuss

the supernatural, and only under great pressure

would the old people reveal that they did indeed

have a

religious system. As in many

indigenous societies,

Eskimo religion was rightfully the domain of

the elders and passed on to the people only by

the

old people.

This circumstance

could

have misled

the missionaries

into believing that pagan beliefs were of little

threat to Christianizing the Eskimo. Yet Weinland

found evidence

that

the Eskimos had

very complex beliefs

about the soul, the supernatural, and life after

death. Working through an interpreter, he recorded

what he

felt was the

basis

of Eskimo

religion.

They believed in both a good & an

evil spirit. The good spirit was in the higher

regions where the crow flies, & hence, they

named him “Crow.” They

did not worship the crow itself as an image of

that god, they did not pray to the good deity,

nor did they sacrifice to him. They simply felt

instinctively

that there was a higher being who was creator & preserver

of the world, & they

taught their children “Do not do anything

bad, for He sees you.

The evil spirit existed, but they had no name

for him, & do not seem to

have concerned themselves any further about

him.

They believe that death does not put an end

to existence-that there is something beyond

this

world. The departed

descends to the lower

regions

by several

stages. At their provision houses they have

a ladder with four steps cut out of a log.

A similar stairway with four steps mark the

four daily stages in the journey to the other

world.

On the first

day the departed

gets

as far

as the first

step, where he must wait one day, the second

day he reaches the second stage, & so

on for four days. Ar the bottom of this ladder

are three rivers. Arrived at the first river,

the departed spends one day in cleansing himself

in this river,

the second day he reaches the second river, the

third day he reaches the third river, where he

must remain a long time, cleansing and purifying

himself in

its waters. Finally, his friends who have preceded

him, come to him & examine

him to see whether he is entirely pure. He has

by this time become almost or entirely transparent.

If they find that he is entirely pure from all

earth-stains,

they rake him along to the realms of the happy;

if not, he is allowed to remain or drift down

the stream, & no more notice is taken of

him (Oswalt 1963a:73-74).

Weinland may have projected

his own beliefs into this account; he was working

through the trader

and the

trader’s Russian-speaking interpreter.

If indeed this is an adequate description of

the Eskimo belief system, then the

Eskimo’s psyche does not seem so far removed

from the Christian spirit. The complexity of

Eskimo culture must have baffled the Moravians

and allowed

them at first to take a benign view of the kashgee.

Nevertheless,

their initial tolerance gave way to severe rejection

when they recognized that

the Eskimo

system

of good and evil

and the shamans

who personified

it were standing in the way of the Moravian conversion

process. Weinland, his wife, and their Alaskan

born baby had a great

deal of sickness,

and after two

years on the Kuskokwim they returned to the States.

For a year John and Edith Kilbuck were the only

Moravians in Bethel.

Kilbuck

was

a Delaware

Indian

and, though a third generation Christian, may

have had

more awareness of cultural

realities than the other missionaries. Though

many missionaries worked at it, he was the first

to

master the Yuk dialect.

As Mrs. Schwalbe

puts it:

Then he began to encounter the shamans

who opposed the work of the missionaries. Even as he gained

a deeper knowledge of the

language there came with

it a fuller revelation of the powers of darkness

and the superstition which

held

the people

in its grip (Schwalbe 1951:17).

Kilbuck recognized

realistically that the kashgee programs were indeed

religious ceremonies, and

hence he felt

the kashgee and

all its functions

should be

destroyed. Functionally he saw the kashgee as

a religious center outside the Moravian

power and that the kashgee would have

to be replaced by the Christian church as the

center of all

community life

in order

to bring

the Moravian Christian

faith to the Eskimos. In a letter to Weinland

in 1890 he wrote:

You remember the masquerades.

At the time we could not condemn them, because

we were unacquainted

with their

nature. Now,

however, that

we know that

they are no more than heathen rites, the one

grand

religious ceremony of the year,

we have condemned them, and seek to suppress

them (Oswalt 1963a:76).

From then on the Moravians

took a firm stand against all Eskimo ceremony, recreational or

religious,

and every Eskimo

rite

became an orgy in

their eyes. The Native

dance-dramas, upon which so much of the Eskimo

social life and prestige depended, were anathema

to the

missionaries and forbidden

to their

converts. Mrs. Schwalbe

recounts from a missionary’s diary one

such “dance for the dead” held

in 1898.

The necessity for some form of amusement

is present with people everywhere, and the

Eskimo with his

inherent dramatic

instincts,

his desire to

move across the stage before his fellows, pursued

his creative ability in

an interesting

style of self-expression. But in this he all

too often followed the lust of the flesh and

allowed

himself

to be drawn deeper

and deeper

into the

intemperate practices of superstition. . .

The dancers are usually girls and women in costume,

wearing elaborate head dresses and carrying dancing

fans. The

dancing is actually

genuflections of the knees and a co-ordinated

movement of the body muscles as they

endeavor

to interpret the song in pantomime. It is often

very skillfully done. Several persons occupy

the floor

at once but dancing

alone. The body

may sway,

but the dancer does not move about on the floor.

The muscles of the arms ripple

and then jerk as they manipulate their fans.

When the body sways and bends, then suddenly

comes upright

again,

these

body muscles

seem to

flow along

with

those of the arms. . . . During and after the

dances, the gifts were brought into the kashige,

and one

or more of

the chiefs

made the

distribution, being careful to observe certain

social codes. Such was the kind of

orgy that took

place in the isolated village of Ougavik that

winter.

The Helmichs were perplexed and naturally discouraged.

Mrs. Helmich’s

diary states that during the rime the skies

were dark and lowering, and their hearts were

dark

and heavy too ... (Schwalbe 1951:77-79).

After

the condemning of the kashgee ceremonies,

the missionaries attacked ceremonialism at every

level.

The goal of change

was to substitute

the Moravian church as

the community center, to strip the shaman of

his leadership position, and to replace him with

the

missionary preacher

and later the

Native lay Christian

leader in each village.

Circumstances and cultural

functions may have made this change from kashgee to

church reasonable. A potent force

for change

was of course

the unswerving

conviction of the Moravians that fulfillment

and

salvation could come only through Christian conversion.

Later

we may observe

secular White

teachers

among the Eskimo teaching with the same consistent

zeal that the “good life” can

come only through conversion to White values,

which basically are supported by Christian conventions.

The kashgee as a community center, the

Eskimos’ own

mystical belief in good and bad spirits, their

belief in afterlife, all appeared, at least superficially,

not to be in conflict with Christianity.

One major

difference between the two systems was the position

of women. The kashgee ceremonialism

and Eskimo

mystique

in general reinforced a subordinate position

of

women. The Moravians

on

the

other hand

offered

women an equal

or at least coordinate role in religious ceremony

and sanctions. The Moravian women whether married

or single

women, were

missionaries in

their own right.

A reflection of this can be seen today in the

village churches; women and children often make

up the

backbone of the congregation

and men

may

come

infrequently or only on special occasions of

celebration. So Moravian Christianity, reversing

the situation

of the pagan

kashgee, supported

the women’s role

and criticized the men’s role. This applied

significantly to the separation of the sexes.

The kashgee was essentially the separate

dwelling place of men.

Here they gathered for relaxation and sought

strength and status in the heat baths. The kashgee was

the men’s house, and women entered

only to bring the men food and on invitation

to take part in general ceremonies; the rest

of the time the women stayed in their own dwellings

waiting for the men to come to them. The Moravians

considered this morally wrong. In the eyes of

the

Moravians the family should live together as

a unit and the Eskimo dwelling was not a home

until it contained the Christian family unit

of husband, wife,

and children. Of course anything less than lifetime

marital fidelity was proscribed as sin.

Over the

years the church came to replace the kashgee,

both as a building and as a community

gathering

place; the house

became

a home,

a family

dwelling place; and the heat baths of the kashgee were

replaced by the smaller private steam bath houses,

adopted from the banjas of

the Russian traders. Here parts of the kashgee functions

were carried

on. Men continued

to be avid

bathers,

and the banjas are still a major focus

of sociability; with the changing status

of women achieved through Christian communization,

the banjas today are used by both men

and women.

Within the kashgee the block

to change was the shaman. Despite the division between

male and

female roles,

some of the shamans

were

women. Kilbuck

saw the shamans as frauds, as well as agents

of the devil, because they used

tricks to cteate magic. Shamans frequently claimed

they made trips to the moon, when

actually all they did was sir on top of the kashgee.

Kilbucks attack on them was to unmask them as

frauds, again striking

at the very

heart of

Eskimo

mystique and wisdom.

Priests of many religions-Navajo

singers, Zuni priests, medicine men of many tribes-indulge

in ceremonial

acts technically

involving tricks;

so,

it might

be said, does the Catholic priest conducting

the Mass. What missionaries label as trickery

often

may be acts

of symbolism

by which the

religious needs of

the group may be fulfilled. It is a question

whether the magical tricks of the Eskimo shamans

were not

understood by the Eskimos

themselves as religious

charades and accepted nonetheless as symbolic.

The tricks as observed by the missionaries were

also

ritual, and

ritual

formalizes

the

style of the

culture.

Medicine men, shamans, religious leaders in general,

are usually intellectual

leaders among their people with keen mystical

and psychological insights invaluable to the

group

and with practical

functions as well, such

as keeping track of

the seasons and predicting the weather. Hence

attacking the shamans as frauds also insulted

the intellectual

integrity of village

leaders, possibly

leading

to significant deterioration in the effectiveness

of Native leadership.

The Moravians, though strangers

to the life and death balance of the Arctic environment,

figuratively

took

over the role

of the

shaman. The question

that must be answered in terms of the modern

well-being of the Eskimos is: Have

the Christian ministers realistically been able

to lead the Eskimos into a fruitful harmonious

existence

with

their ecology

as did

the Native

spiritual leaders? As significantly we must also

question whether the

White schoolhouse

has adequately replaced the kashgee as

a school for a fulfilled survival in

the Arctic village and ecology. Moravian White

education offered the Eskimos survival by technologically

mastering

nature and

environment whereas the

Native shaman offered survival by achieving an

equilibrium with the forces of nature.

Hence White schools are oppositional to Eskimo

mystical as well as technological relationship

to his environment.

The

school

has replaced

the kashgee,

but does not offer Eskimos a life center that

this communal gathering place offered the traditional

village.

Certainly the missionaries were dedicated

teachers, willing to risk their lives to bring

their conception

of enlightenment

to

the Eskimos.

John

Kilbuck, by

kayak and dog sled, visited the most remote villages.

His generosity, friendliness, and also practical

medical skills

made him welcome

wherever he went. Yet

the missionaries’ progress was discouragingly

slow, in part because the Moravians did not consider

conversion an easy process. Where the Russian

Orthodox had

been content with immediate baptism, the Moravians

required of the communicants a high degree of

conscientious instruction in Christian precepts

and commitment.

In the third year eight Eskimos were admitted

into full membership in the church. All of these

had been baptized earlier in the Orthodox church,

yet Kilbuck

held them off for a year after they had first

asked for membership, testing their consciences

and preparing them for this important step. Kilbuck

wanted

complete conversion and complete rejection of

pagan Eskimo self and also “a

profession of faith in the Triune God,” for

interpretation of the doctrine of the trinity

was a major point of theological difference between

Orthodox

and European Protestant beliefs (Oswalt 1963a:75).

The

Moravians appeared as disturbed by some aspects

of Russian Orthodoxy and Catholicism as they

were of outright

paganism.

In the eyes of

the mission they

may have looked the same, and understandably

so. Eskimo paganism was deeply rooted in animism,

mystery,

and

the forces of

nature. Russian

Orthodoxy

built irs strength on pageantry and mystery and

was able to align itself harmoniously

with the nature worship of the Eskimos. This

has its counterpart in the Catholic missions

in the

American Southwest that

have also related

peacefully

across

the mysteries of Pueblo Indian nature-oriented

worship. The Moravian’s

insistence on total surrender of Eskimo self

slowed the conversion of the Eskimos, for the

Eskimo personality was inexplicably bound up

with their total relationship

to their natural surroundings.

The Kilbucks must

have felt the cultural wall between the missionaries

and the Native self.

The Eskimos

came to the

mission friendly

and grateful, accepted

Christian kindness, and then retreated into the

pagan darkness of the villages. How could the

Gospel carry

across this

gulf? One method

was

the initiation

of the “helper” program, enlisting

the dedication of converted Eskimos to carry

Christianity into their own villages. The first

two helpers

were consecrated by the Moravian bishop on his

visit to the mission field in 1891. Several villages

had been singled out for intensive proselytizing,

and

to each of these a helper was appointed. These

men aided in the church services and influenced

fellow villagers to accept the Christian teachings.

They became

the eyes and the ears of the missionaries, reporting

every strength and weakness, who was ready for

conversion, and who was slipping away. The missionaries

would

then make personal visits to these members. The

helpers worked right alongside Kilbuck in his

preaching, supporting the lesson of the sermon

wherever his

command of the Eskimo language broke down. This

innovation greatly accelerated Christian education

and opened the door to sweeping changes within

the villages.

For example, the village of Kwethluk, under the

pressure of a vigorous religious helper, was

persuaded to burn all their ceremonial masks.

The Moravians would

indeed have been slow in reaching the Eskimo

heart without the aid of the religious helpers.

Several Eskimos were ordained as ministers in

the early years. Today

Native assistants who are called lay pastors

are still the core of church strength in the

villages.

A high point of success came when

the son of a famous shaman, trained to follow in

his father’s power, joined the helper program.

Helper Neck appeared to be an exceptional example

of a Native who did move from a leader role in

Eskimo culture to leadership and responsibility

within the Christian value

system without losing the integrity and effectiveness

of his Eskimo personality. He retained his special

position of insight and influence and dedicated

himself

to overthrowing the shamans’ power, fighting

fire with fire. The missionaries referred to

him as “the Apostle to the Eskimo.” Helper

Neck devised his own intricate system of writing

to present Christian teachings in the Eskimo

language and taught the system to his co-workers.

He was the earliest and probably the most outstanding

Native teacher among the Kuskokwim Eskimos.

The

Moravians seized upon the value of Native teachers

to spread the Gospel, but they did not

reason from

there that

Natives

could also

be instructors

in their White schools as well. We have no record

of Natives being used in the

classroom in the effective way that the Eskimo

helpers were used to carry out grassroots Christian

education

in the villages.

We appreciate that

from the

beginning schooling centered around teaching

English as a means of reading and writing, and

Eskimos

would have

had

to master

English before

they

could function as English teachers. But if the

Moravians had appreciated that

Eskimo teachers teaching in Eskimo could have

been as persuasive and effective as

Helper Neck in presenting concepts, they might

have summoned the patience to train educational

collaborators

as well.

SHIFTING

ECONOMIC

CURRENTS

We

cannot consider the human effect of the American

take-over of

Alaska without a careful

look at where the Eskimos appeared to be in 1884

when the first Moravian

missionaries

arrived on the Kuskokwim. Earlier reports make

it appear the Eskimos changed very little under

Russian influence. Weinland

and Hartman,

like Sheldon

Jackson before them, were shocked at the “plight” of

the Eskimos, probably a shared response of culture

shock at the severe life style of the Eskimos.

Some eighty years later Edward Kennedy stood

on the banks of the Kuskokwim and expressed the

same shock at the simplicity of the Eskimo village.

In sincerity he too saw Eskimo life style as

poverty.

There is little evidence that the

spiritual and social structure of the river Eskimos had

changed

or decayed

appreciably. The kashgee described

by Zagoskin

and the kashgee described by Weinland

forty years later were

the same, except that the giving away ceremonies

had been enriched by new trade

items. Within

the twenty-year period between the departure

of the Russians and

the arrival of the Moravians, the general economy

of the Kuskokwim had

begun

a process

of economic and commercial change that has continued

accelerating into the still unresolved conflict

of contemporary Eskimo

life in Alaska.

To discuss the changes that began

with the American purchase of Alaska we must

trace through economic

variables and

speculate on

the effectiveness

of missionary

education to equip the Eskimos to meet the invasion

of American commercial values into their lives

then and

now. Certainly

the Russian American

Fur Company began this invasion, but within a

different cycle of history and

by a different