Foreword

ABOUT THE SERIES

This series brings to students the

results of direct observation and participation in educational process, by

anthropologists, in a variety of cultural settings,

including some within the contemporary United States. Each of the books

in this series is selected as an enduring example of educational anthropology.

Classrooms, schools, communities and their schools, cultural transmission

in societies where there are no schools in the Western sense, all ate

represented

in the series. The authors of these studies move beyond formalistic treatments

of institutions to the interaction among the people engaged in educative

events,

their thinking and feeling, and to the educative transactions themselves.

Education

is a cultural process. Every act of teaching and learning is a cultural event.

Education recruits new members into society and maintains

the culture.

Education may also be an instrument for change as new adaptations are

disseminated.

Generalizations

about relationships between schools and communities, education and society,

and education and culture become meaningful when education

is studied as a cultural process. This series is intended for use in

courses in education, and in anthropology and the other social sciences, where

these

relationships

are particularly relevant. They will stimulate thinking and discussion

about education that is not confined by one’s own cultural experience.

The cross-cultural emphasis of the series is particularly significant.

Without

this perspective, our view will be obscured by ethnocentric bias.

ABOUT

THE AUTHOR

John Collier’s qualifications are those of

a fieldworker and an observer of culture. In his role as photographer he has

brought

special sensitivity

to recognition and recording of the field circumstance.

Collier’s

first fieldwork was in the early forties with the Farm Security

Administration photographic team led by Roy F. Stryker. Here, working with

Edwin Rosskam, Arthur Rothstein, John Vachon, Jack Delano, and

Russell Lee, Collier was educated in the social and economic content of the

documentary

visual record. When Stryker moved from government to industry,

much

of his staff moved with him, and Collier spent four roving years

recording the role

of petroleum as an agent of change, from the arctic to the tropics.

This experience brought him to the challenge of cultural significance

in photographic imagery.

In 1946 Collier collaborated with Anibal

Buitron, Ecuadorean anthropologist, in an experimental study to record with

the camera the complexity

of culture and processes of change. The Awakening Valley,

by Collier and

Buitron,

reported on this effort of combining photography and ethnography.

From

this point Collier moved directly into anthropology. For three

years he worked as a research assistant with Dr. Alexander

H. Leighton,

of

Cornell University,

exploring and testing our various photographic methodologies

that could open the door to the nonverbal content of culture.

These

studies included

cross-cultural

fieldwork in the Maritimes of Canada and the Navajo Reservation.

Next Collier worked for a year assembling for Dr. Allan R. Holmberg

a photographic

baseline

of the culture of Vicos against which to evaluate change in the

Peru-Cornell Project. A comprehensive photographic ethnography

was prepared, which

awaits publication.

For the past ten years Collier has devoted

his time to teaching and research in visual anthropology. He has worked consistently

in the

area of acculturation

and the welfare of American Indians and more recently in problems

of Indian education. After his film study of Alaskan Eskimos,

Collier continued this

educational research in the Rough Rock Demonstration School

in Arizona.

Collier has lectured at Stanford University, the

University of California at

Berkeley and Davis, the University of Oregon, and the University

of Washington.

He is now an associate professor in Education and Anthropology

at California State University at San Francisco and also reaches

creative

photography

at the San

Francisco Art Institute.

About the Book

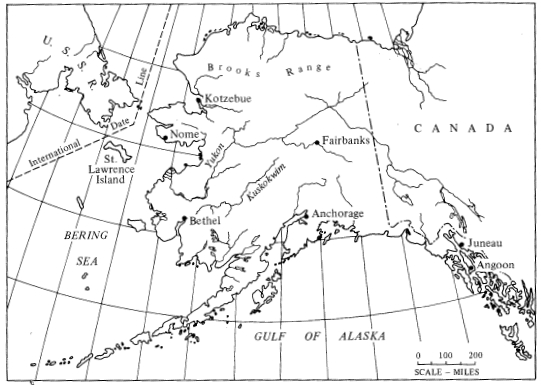

This is a study of the

educational process where the teacher and the student represent

different communities. The settings

for the

study

range from

schools in isolated Alaskan villages attended only by Eskimos

to schools in Anchorage

where only 7 percent of the student body are Eskimo, Indian,

and Aleutian. The research is unique not only because it was

done on

a wide range

of communities but because it was carried our by an anthropologist

using film and tape as his major data collecting devices. The

procedures used and explained by

John Collier in this case study enabled him in a comparatively

short period of time and with twenty hours of film as data

to produce a substantial and

very insightful analysis of education.

Perhaps because of his use of motion

picture photography as a research technique, his analysis calls

attention to the elemental

rhythms

of interaction and

movement within the classroom. The teacher who moves into and

becomes a part of the

circle of children, the teacher who talks to the empty seats

in the classroom at a great distance, the teacher who is oriented

to the

individual tasks

of individual children, and the children themselves, involved

and

spontaneous or bored and sleepy, come through in a way that

is

rare in the literature

of

schooling and education.

The insights into educational process

to be gained from this case study are not limited in their

application to Eskimo or

Indian

education alone. The

teacher in every school in every classroom is in some measure

separated culturally from his or her students. The separation

and insulation

of the teacher is

more

severe in the cases described by John Collier than in many

schools in the United Stares, but the elements of interaction

and communication

are perceivable

and

held in common in all schools. Conversely, the elements of

effective teaching and productive learning are identifiable

and applicable

to

all

schools.

In this case study it is clear that education is a transaction

dependent upon

interaction and empathy.

The case study also raises questions

about the relevance of what is taught. It is not merely a question

of whether

Eskimo

children

should

he taught

about the culture and technology of the Whiteman in, say,

Seattle, Washington, but rather one of how the knowledge

about Seattle

shall be joined with

an

understanding

of the environment in which the Eskimo child is living.

If the teacher is sealed off from this environment both physically

and

psychologically,

the

probability

that a viable joining will occur is remote. This generalization

applies to any school any place.

George and Louise Spindler

General Editors

STANFORD, CALIFORNIA