1/Perspectives

THE CHALLENGE OF ESKIMO EDUCATION

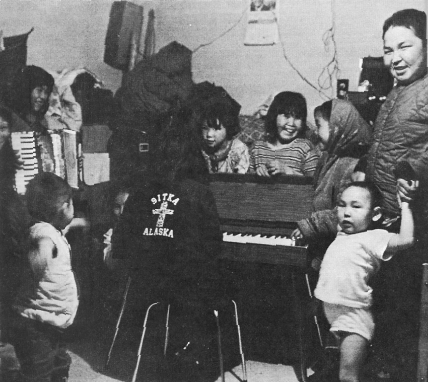

The potential of an Eskimo future.

Education for Indians and Eskimos is part

of a century of effort to place them successfully in the mainstream of

American life. The federal effort to educate Indians was a treaty obligation

born

out of the Indian wars and the Plains Indians’ final defeat at the

massacre of Wounded Knee. It seemed not unreasonable at that time to consider

education

as a terminal experience that would close the history of the Native American.1

But

the Natives have not been assimilated, not have they vanished. Rather,

they have rapidly increased their number and are now a fast growing minority

in the United States. Indians have demonstrated the need to be Indians,

to be themselves, and even today this continues to be a perplexing problem

in

schools and acculturation in general. Too often education has resulted

in conflicts demanding extreme personality change. For this reason, among

others, Indian education has continued to be a negative experience.

Education

for Native Americans is a controversial issue because-despite millions spent

by federal, state, and public schools, and by the churches-Indian students

too often appear less equal than ever before, as personal fulfillment

becomes increasingly difficult in modern society. Generally schooling has

not opened

pathways to equal opportunity, psychologically or economically, for

these culturally different students. Rather, the quality of their education

has placed thousands

of Native Americans on relief and many thousands more in the ghettos

of cities-far too many. In a shocking way, the more they go to school, it

seems,

the less

effective they become as human beings.

How should the White society

educate the Red or Brown American? In search of an answer the U.S. Office

of Education funded a National

Study of American

Indian Education, in an eleventh hour effort to salvage Native American

education and to assist teachers in this task wherever Indians are

in school. The film

study of Eskimo schools was one unit of the National Study.

Under

the direction of Robert J. Havighurst of the University of Chicago, the National

Study conducted an extensive survey, with regional

reams

all over

the United States following the same program of testing instruments

and scheduled interviewing.2 Anthropologist

and educator John Connelly, of San Francisco

State College, was contracted as regional director for the Northwest

Coast and Alaska. Connelly invited me to add a visual dimension

to his evaluation

by film research. It was hoped that this direct observational study

would qualify the more abstract verbalized findings of the formal

analysis.

The fieldwork was carried out in the spring of 1969, largely

in the area of Bethel, an air hub and trading center on the Kuskokwim

River

in West

Central Alaska. Here in the tundra along the winding waterways

of the Kuskokwim the

Eskimos live in many tiny fishing communities, each with its

community elementary school operated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Neat

one village a Moravian

Mission ran a children’s home and their own eight-grade

school. In Bethel itself the consolidated elementary and high

schools were

operated by the State

of Alaska. While Connelly and his assistants, Ray and Carol Barnhardt,

concentrated on the larger schools in Bethel, I began my film

study in the remote river

villages, then moved in to Bethel, and finally to the municipal

public schools of Alaska’s largest city, Anchorage-covering

more than forty educational situations and collecting for analysis

some twenty hours of classroom

film data.

The purpose of the film study was to track the well-being

of Eskimo children through all varieties of school environments

of this region-mission

schools,

BIA schools, state schools, city public schools. In the following

year the film data was systematically analyzed and evaluated

by a team of

four San

Francisco State College students and graduates with training

in both education and visual

anthropology. A final report, combining their judgments, my own

judgments, and my empirical field experience, was submitted to

the U.S. Office

of Education, and the bulk of this material has been incorporated

into this book.

Perhaps I should have gone north with no preconceived

ideas about Native education, but this was not the case with me nor with

most of the members

of the National

Study teams. Though my knowledge of Eskimos was limited, I

had experienced years of interaction with policies of the Bureau

of Indian Affairs

(BIA) and Indian education in other areas. Earlier fieldwork

on the Navajo, and

more

recently a study of Indians relocated in the San Francisco

Bay Area, had already raised in my mind serious questions about education

for

culturally

different

children. This certainly affected my research and directed

my observations, indeed may even have weighted my view. Critically

I was observing

within an anthropological frame of reference and checking on

many circumstances

of education

with which I was already familiar. Further, I had come north

from eight years of seminar experience with college students

working

for teaching

credentials,

so I was bringing to my focus not only problems of Indian education

but the challenge of American education in general. As I filmed,

questioned, and

listened, I was seeking answers for many problems and clarification

for many dilemmas

that have generally confounded education across cultures.

Also,

I came north with the belief that there is success in Indian education,

though it may be less easily defined than

the more

pervasive failure. I was

seeking a fulfilling classroom where positive and additive

learning took place. Such a model could offer teachers a

foundation point

for adapting

learning

for the culturally different. The first and basic question

was: What developments might be needed in Indian education?

I hoped

some fine

teachers would show

me these needs. Beyond what teachers could demonstrate, I

wanted to broaden the focus of the challenge away from conventional

goals and

standards into the emotional and cultural considerations which might lie

far beyond the common expectation of what makes a school effective.

It is native

to our American system to believe that success can be measured in monetary

and technological accomplishment,

and

that dollar-rich

budgets

can relieve the basic problems of deprivation. An equally

spontaneous approach has been to find villains and scapegoats.

For years

critics have pommeled

what they considered “inferior” teachers and

decried the material poverty of Indian schools. What if

our study found the schools

excellently

equipped

by contemporary standards and the teachers both dedicated

and well trained? What if we found that the best equipped

schools and teachers fared no

better or worse than physically drab, ill-equipped schools

with minimally trained

teachers? What would we face then? We were alerted that

the issue might not be the professionality of the education

provided,

but the kind of

education and the kind of practices followed in teaching

the emotionally and intellectually

different Native child.

To appreciate how I filmed and what

I observed in Eskimo schools, we should share together

what I feel is the significant

relationship

between

culture

and learning, for this relationship is the major focus

of this book. An important view I share with many colleagues

is that

there is a

great difference

between schooling and education. As Robert Roessel, first

director of the culturally determined Rough Rock Demonstration

School

on the Navajo,

puts

it, “Education

is everything that takes place in life.” Schooling

is a limited aspect of the learning experience. With this

view, conceivably the larger

and

often the most important education takes place before school,

continuously outside of school, and long after school. A powerful education

can be obtained with no school at all. In a lifetime experience

with Indians in the Southwest,

I

have been impressed by the acuteness and intellectual effectiveness

of unschooled Pueblo and Navajo Indians, who often respond

to complex modern

legalistic challenges with more grasp than school-trained

Indians. Does this suggest that

Indian children can lose intelligence by going to schools?

Or is it simply very difficult to use Indian intelligence

in White programs? Throughout

this study, total education rather than the interlude of

schooling is the large

concern. We want to know how schooling affects education,

additively or subtractively. In the same reference we are

concerned with how schools

affect learning and

the development of intelligence.

California schoolteachers

frequently view their Indian students as unintelligent

or retarded. This impression

may have a

basis of accuracy,

for certainly

many Indian students perform at a low level. The question

the anthropologist must

raise is: Do they enter school retarded, or do they become

retarded through schooling? One of the casualties of acculturation,

moving

from one system

of values to another, is that effective intelligence can be left behind.

An anthropological view of intelligence

is that it is both learned and expressed within a cultural system. Ruth Benedict

(1934)

refers to this

phenomenon

as the “language of culture,” through which

man develops, communicates, and solves his life problems.

The cultural language is the total communication

of group-shared values, beliefs, and verbal and nonverbal

language. The intelligence of the Native child must

be observed in this communication context. Behavior

outside one’s own system can appear unintelligent.

It is generally accepted that much of basic intelligence

is formed in early childhood

within a

particular environmental program. Acuteness of mind rests

within the first language, and the initial intelligence

rests upon experiences in the first environment, whether

that be desert, jungle, or Arctic snow. From this is

born

the resourcefulness

and intellectual vigor

that we hope will be the equipment of the child as he

grows. This presents the dilemma that it may be difficult

and

sometimes impossible

to utilize

full intelligence except within the cultural system that

nurtured the child. It

is this challenge that presents crosscultural education

as a

conflict between cultures, deeply involving the personality

and culture

of both teachers

and students.

In this perspective, effective education

could be the degree of harmony between the students’ culturally

and environmentally acquired intelligence, and the learning

opportunities and the intelligence-developing procedures

and goals

of the school. Reasonably, if significant conflict lies

between Eskimo processes and the school, some variety

of educational failure must be expected. Teachers

may be seen reaching ideally with the flow of Native

intelligence, or teaching negatively against the Native

stream of consciousness. Granted, these are subtle

energies, but they are there to be utilized or ignored,

and they may well make the difference between a motivated

or a “turned-off” classroom.

Western life

style and technology have drastically altered the Eskimos’ relation

to the Arctic, as indeed they have altered indigenous

life throughout the world. Realistically then, what should

be the goals of schools in

preparing

Natives

to survive in drastic and rapid change? Can schools offer

needed new skills to cope with modern economic survival

without weakening essential

Native

learning for success in the Arctic environment?

Because

historically education for Native Americans was essentially

the conflict waged to change the Indians

into White men,

I was prepared to see stress

which often places the Native child in conflict with

his own personality-stress resulting

either from failure in mastering the school culture

and hence failure in the teachers eyes, or stress from success

in mastering

White

style. Successful

White education could become the double bind that leaves

the child in a chasm between two worlds.

A significant

question is: What is success in the eyes of the White educators?

Relocation away from the village?

Partial

or complete

rejection of Eskimo

self? Are students often left in the traumatic confusion

which

may be associated with disorganized change? Workers in

the field of Indian

education have long

been concerned over the high dropout rare, among Indian

students, and the later

inability to cope with modern cultural and economic life.

Other ethnic minorities, notably Spanish-American children,

respond

in similar

ways to comparable circumstances. I was equally concerned

about this confusion

of

personality

which seemed to freeze effective development.

Do White

teachers of Eskimos limit further the resources of their students by their

attitudes toward the Eskimo

life style?

White

people in Alaska

are heard to say, “The villages have lost their

economic function. There is no future for a bright

well-educated Eskimo boy in the villages.” Is

the intelligence of the child locked significantly

into the vitality of his village and the Arctic life

style,

so that if we condemn the villages,

we are

also rejecting the emotional well-being of the child,

in school and out? In this light, is White education

a support or an assault upon Eskimo

vitality?

Can we consider well-being in education without considering

the solidarity of Eskimo life in the Arctic? Is there

no place for Eskimo culture in

modern survival education? Where and how could Eskimo

skills be incorporated into

the schools?

White education on the Navajo Reservation,

whether missionary or BIA, has in the past consistently

rejected

Navajo-ness

from the

schools, as if to

say, “Hang

your culture outside, and take a shower before you

come to class!” Even

today the first step in a BIA kindergarten school on

the Navajo is to strip the clothes off the youngsters

and soap them down before they are allowed in

the classroom. However hygenic this may sound, and

however economically practical the White teachers’ dim

view of the Eskimo village may be, both reject symbolically

and conceptually the Native children from the White

education

in the school. Let us be very clear: I am not talking

about any single

kind of school-missionary, BIA, state, or public. We

are simply discussing and observing

what is happening to Native children in White schools.

Ironically, comparable rejections affect many White

children, as well as other ethnic minorities

in American education.

Traveling north my plane left

Seattle and flew over four hours of snowbound wilderness.

Surely the far

Arctic

is the outpost

of the

American continent.

Here we could observe again the historic contact of

modern White culture with ancient people, the Eskimos.

The wilderness

was

vast beyond any

of my conceptions.

Schools were dots on the tundra; villages, clustered

dots by frozen rivers or coastlines. But when I entered

the

village classrooms, I sensed that

I had not traveled far. Here was the familiar conflict,

the distance that frequently

isolates teacher from students. I was immediately impressed

that there were aspects of the Eskimo classroom that

were shared

with

the inner-city

schools

or the Spanish-American schools in the Southwest. In

greater dimension,

I sensed I was witnessing the conflict involved in

the westernization of ancient

societies,

or of affluent American education’s attempts

to communicate with and ideally to “uplift” students

from poverty’s community. The

Eskimo world has been called the ghetto of the north,

or in the words of Edward Kennedy as reported in the

Anchorage press, “the Appalachia of the Arctic.” How

pervasive is this view? Are teachers able to break

away from this ethnocentricity and educate Eskimos

as Eskimos?

Intrinsically this book is a report of “White

Studies” for

Brown students, and the hardships and frustrations

of administering such a curriculum

laid down by culture-bound White values. I approached

the Eskimo world as an isolated microcosm where the

familiar circumstance of the crosscultural

dilemma

might be observed and its simplicity might offer fresh

insights that would be useful to the Hong Kong Chinese

immigrants in San Francisco

as well

as to the Eskimos and the American Indians.

Our queries

may appear to go beyond the scope of our film data

of Eskimo classrooms. Factually stated, they

certainly

do.

But the drama

in these

classrooms goes

far beyond the teachers’ fulfillment of their

professional roles. To give justice to the efforts

and the generosities of these men and women, I

feel the real challenge of their assignments must be

appreciated. Positive education for Native Americans

has baffled educators for decades. Brilliant

schemes have been introduced and millions of dollars

spent, with small return. I approached my Eskimo classrooms

with this perspective, and all that

has been written is toward appreciating the scope of

the challenge. The landscape of education I am trying

to describe is particularly critical for

Eskimo and Indian students, but the dilemma is shared

with all children who are different-Red, Brown, Yellow,

Black, or White. Basically the challenge

is the right to be one’s own self, whether this

be the personality of a single individual, or the collective

personality of a group. I move forward

in this writing, as I did in the field experience itself,

seeking an educational definition that offers people,

no matter how different from others, a productive

place in the modern world. I write with conviction

that not only are people and peoples inherently unique

but that civilization is enriched and tempered

by this diversified vitality. I see Native education

(and there are Natives everywhere among us) as utilizing

multitudes of cultural energies without which

a free and equal world may never be formed. The pages

to come describe the varied effort of many teachers

to deal with this challenge. The descriptions

of classrooms will share with you questions that remain

unresolved: Why are we educating Eskimo students? Why

do well-trained teachers so often choose

to teach in the lonely school posts of Eskimo villages?

And if Eskimos were genuinely offered equal educational

opportunity, what would be the content

of this experience?

FLIGHT THROUGH TIME AND SPACE

My

winter departure from civilization and modernity of

the “Lower Forty-Eight” was from Seattle-Tacoma

International Airport. Flight northward was toward

the Arctic frontier where symbolically man’s

survival still is within the grip of nature. Flight

into the Arctic winter dusk from Juneau to Anchorage

is surely over

nature’s domain-no track of road, no human sign,

hour after hour of tundra land, icebound shorelines,

and treeless mountain ranges. But this expanse,

north to the Arctic Ocean, is the home of 53,000 Eskimos,

Indians, and Aleuts, scattered over a half million

square miles of tundra and forestland. It was

hard to conceive of modern enterprise emerging out

of this wilderness. It was hard to imagine man’s

living at all in such bleakness!

But in a few minutes

I would be arriving at the city of Anchorage. Mountains

suddenly leveled, and in the

distance

was an impossible

blaze of lights-the

city. The lights fanned out in a maze of brilliance.

Ahead were the homes of 40,000 White men and an estimated

5,000

Native Alaskans.

The plane

was lowering

fast. The wilderness was scattered. Blinking neon signs,

red and blue, and ribbons of car headlights illuminated

tall buildings

and

windows

of tiny

homes. Suddenly the wilderness that had been majestic

and timeless seemed fragile.

Only a few decades ago Anchorage had been a railroad

construction camp. Now Anchorage was any small American

city that had

grown too fast.

Gaudy bars,

secondhand car lots, and glass-encased, self-consciously

modern buildings, with piles of dirty snow. Sharply

dressed men, girls

in miniskirts

despite the cold, American construction men in boots,

fur caps, and cowboy hats.

Here and there a Native-Eskimo women picking their

way with care in sealskin mukluks,

quiet Indian faces drifting along, bright eyes of a

few Native children, oblivious to the modern pace and

mechanization.

Here was a model

of what American know-how

could do with the Arctic wilderness. As in any American

city,

cars

streamed by, grinding the winter into black asphalt.

Multitudes came in by plane,

but as many more came in cars from California and Oklahoma-campers,

trailers, wagons,

sport cars. The wilderness was broken by the Alaskan

Highway and by the constant air streams flowing to

and from the “Lower Forty-Eight,” Europe,

and Japan.

My second journey through time was from Anchorage

to Bethel, a western trading center on the second largest

river in

Alaska, the

Kuskokwim,

which flows

from the mountainous interior to the Bering Sea. The

city of Bethel-would it be

ablaze like Anchorage? Wien Consolidated Airlines canceled

the morning flight: snow. Nature had intruded!

The flight

to Bethel was into an Arctic wind and flurries of snow. The plane interior

was shabby with use. Freight

was lashed

down

where passenger sears

had been. An all-Eskimo detachment of National Guardsmen

climbed aboard, on their way home to villages after

a training period

near Anchorage.

They were

heavily dressed in snow packs, army parkas, and ear-flap

caps. They filled the plane with gentle laughter

and pressed their

noses against

the windows

as we angled upward in a deafening burst of jet engines.

We

circled for altitude, leveled westward as Anchorage began shrinking, and

finally disappeared in the grandeur

of desolate

white peaks.

The wilderness

closed beneath me again. No trails, no sight of

man. For the next two hours it was incomprehensible that

we would

see man

again;

but we would,

the

miracle would happen, and out of nowhere would

come the small city of Bethel.

When our plane crossed the peaks of the Kilbuck

Range, a hundred miles inland from the sea, we

were over

the tundra lands of

the Kuskokwim. As we descended

to land at Bethel, we came in low over the river

that meandered west in tortuous coils between dark

shorelines

of willow

and spruce. There

were

trails of

men here! Lines of sled and Sno-Go (snowmobile)

trails up

and down the frozen river

to villages near and very far, located on the river

banks or on equally coiled river tributaries. Here

the river

Eskimos have thrived

with

a precarious balance of fish, berries, rabbits,

ducks, caribou, moose, bear, and an

occasional

seal

swimming from the sea. The Eskimo villages were

here when the

first White

man came two centuries ago. How much longer will

they remain? Along with our Eskimo

passengers were Army officers and city-dressed

men with galoshes, overcoats

and attaché cases. Why do they come? What

schemes are in their heads? The very vacuum of

the wilderness seems to draw White men into

the Arctic,

each a messenger, like myself, from the modern

world.

After experiencing Anchorage, the emptiness

of the Arctic seemed deceptive.. How rapidly it

was

overrun

in three

years in the

Gold Rush! And now

oil, minerals, and civil and military aeronautics.

The air highway to Europe

leads over the

North Pole. And every square mile of the wilderness

is contended for as a potential sportsman’s

paradise, which covets every salmon, polar bear,

and moose. Modern men change nature and, of course,

the lives

of

the Native people. Change

them into what?

Wing flaps down for landing. Sno-Go

and sled tracks below us converged on the straggled

river front

settlement of Bethel, a scattered

mass of black

buildings

sending up plumes of steam. Bethel was not like

Anchorage yet.

Bethel is principally an airport

center for western Alaska, a defense base left from World War II,

still with the

helterskelter look

of a habitation

of hastily thrown-up buildings and Quonset huts.

Bethel is an

Eskimo city, for

Bethel is the hub of a score of Eskimo villages

located 5 to 80 miles east and west along the

Kuskokwim waterways.

But Bethel

is

also a

bridgehead of

modernity in the tundra. I felt I had stepped

back in history, for Anchorage was such a bridgehead

for White

enterprise

fifty years

ago. But nature still

holds Bethel in her grip! No water system, no

sewage. Water is purchased by the barrel, and human waste

removed by

the

bucketful.

In the schools

in Anchorage

7 percent of the students are Natives, but here

in Bethel the consolidated elementary and high

schools

are dominated

by an

85-percent Eskimo

student body. Bethel is an Eskimo city. Would

the White invasion tip the balance

of this

culture? Soon?

Bethel is an island in the tundra

with barely twenty miles of roads. But cars moved grotesquely

through

its streets,

past Eskimos

on

snowmobiles and

masses

of Natives and Whites walking over frozen roads

to and from the Post Office, the state liquor

store, and three

major

trading posts that

straggled along

the river. Below river pilings teams of sled

dogs were tethered, wailing and barking while

the Eskimo

owners

traded or just

visited

in the metropolis.

Icy

winds blew up and down the river or across

the desolate

tundra, driving against long squirrel and muskrat

skin parkas of

the Eskimo women,

or against the

surplus Air Force high-altitude clothing popular

with so many Eskimo men.

My third journey back

in time was from Bethel to the isolated village of Tuluksak that lay

eighty

miles

eastward up river

on a tributary

of the

Kuskokwim. Seattle

to Anchorage to Bethel and now to journey’s

end, Tuluksak. Air wings had become smaller,

a single-engine bush plane, equipped with

skis and

loaded with parcels and freight. Village

landings would be on river ice.

We gained

very little altitude and flew eastward across

the loops and bends of the Kuskokwim River,

following, as it were, the multitude of sled

trails

with

now and then

the tiny shapes of a dog team coming or going

from Bethel. Twenty minutes later the plane

dropped down even closer. Tuluksak lay ahead,

pointed

out by the

pilot. Tuluksak is a village of the tundra,

another dot on the map of Alaska, a black

design of tiny dwellings, where one hundred

and fifty

Eskimos,

one White VISTA worker, and two White teachers

survived together through

the winter

isolation.

The plane settled down for a ski

landing on the river ice. Log and frame dwellings

flashed

by,

the bright

buildings of the Bureau

of

Indian Affairs

school, the

steeple of the Moravian church. Dark winter-clad

villagers descended the snow banks of the

river to the metal

bird that links the

village to the world.

Mail,

relief checks, newspapers, a hundred pounds

of dog food. And I, the stranger, descended

to the

river

ice; another

White

man had

arrived.

Eskimo children

helped me with my gear, and I entered the

village world amid wild barking of staked-out

sled

dogs.

Journey’s end was this village

along a small frozen river. There was a tiny

Native store, an even smaller post office,

a white and green

painted

Moravian church, and clusters of log and

frame houses that loosely formed a village

square or fronted on meandering pathways

leading along the

high rivet

banks. Aside from the barking sled dogs it

was very quiet. A few figures emerged, disappeared,

or reentered dwellings. A village asleep

in the

Arctic half light.

Further beyond lay the BIA school compound,

discrete from the tiny log houses of the

village.

The village of Kwethluk, twice the

size of Tuluksak, has electric lights,

a brightly

painted BIA school,

a Moravian

church, and

a Russian

Orthodox

church.

Why had I come? Why had the lone

young man VISTA worker come? Why had the BIA

teachers,

man and

wife, come

and remained

teaching in the Arctic

for

twenty

years? White teachers first came to the

Kuskokwim to change Eskimos into Christians.

I came

to observe how

White education

affects

the Eskimos. But

we all came,

in our separate ways, because we considered

the Eskimos in deprivation. The missionary

teachers

came because

they believed

the Eskimos

had no concept

of the soul. The BIA had sent teachers

because they found the Eskimos

unhygienic and inept in mastering White

ways. The VISTA worker came because he

believed

the village low in modern skills and

community enterprise. I also came over anxiety about

skills-skills either

not taught in the

White school

or blocked

by the White school by interfering with

Native survival learning of how to live

in the Arctic

ecology. My

concern was whether

education was helping

Eskimos

live in the real world as Eskimos. But

as an observer and an evaluator, I came

as a

White

man like a

hundred others

who

at

one time or

another have

descended

on this tiny dot of a village called

Tuluksak.

How far back in time was this village?

At what point in Eskimo destiny was White

education

attempting to meet the

village’s need? Here

my study of Eskimo education began-in

the most remote village in a two-teacher

school

in a community reputedly involved in

the subsistence survival of the Arctic.

I was dropping in from the skies into

two centuries of aboriginal-White

contact culminating in Eskimo survival

today. Within this history was the BIA

school,

built close on the edge of Tuluksak.

I

was impressed with the human warmth and

skill of the BIA teachers when I

entered

the Tuluksak

classroom.

The

first-,

second-, third-,

and fourth-grade

classroom was a very cheerful room decorated

with bright prints of farm animals and

cutouts of paper

flowers.

The room was

wonderfully clean

and orderly;

the children, cheerful and well-behaved

if a bit sleepy. The teacher moved about

the

room, gently

prodding or

encouraging, speaking

in

a clear and

friendly voice. The school was exceptionally

well-equipped for a rural village of

a 150 people. There were bright toys,

White dolls,

modern trucks,

and a full library of children’s

books. I remembered seeing equally well-equipped

new schools on the Navajo Reservation,

where I had also

worked with some

very dedicated teachers.

For many reasons

this well-run school was a baffling place

to begin observing

educational

processes

that were, in

many eyes,

failing

the needs of Native

students. The teachers, living in their

well-run home in the same building as

the classrooms,

were skilled

in their

style

of life,

but even on

first contact appeared far removed from

the lifeway of even the most modern

Eskimos of this

remote village. All that I could note

down from this first visit was that the

school

compound

was a confrontation

with Eskimo

life. Was

there anything

wrong with this? Isn’t education

generally a confrontation? Certainly

I would have been bewildered if this

mature couple were trying to live

like Eskimos. Instead these teachers

were sincerely being themselves and living

the properly fed and housed White style

that suited their personality

and background.

Two years and several

months later I still feel evaluating

Tuluksak baffling

on an

immediate classroom teacher-to-student

relationship.

It is difficult

to write about this school without

first considering the total context of the

White confrontation

with the Eskimo.

To evaluate

education

for Eskimos,

I find

I must consider the total history and

drive of

White intruders, which include myself,

and more than two

centuries of Western

influence on Native life.

We must weigh the actualities that

have been imposed on Native survival

over the

centuries of White contact. If we can

do this we might conceive of a modern

Eskimo

and the

world

in which

he could survive

now. A distortion

of the educational

dilemma could occur when we lose this

whole view. What the teachers were

giving their

students in Tuluksak was real,

but maybe only

one part of the

real that

Eskimos need to survive now. Before

traveling further we should pause to look at the

history and the

emerging ethnography

of

the Kuskokwim

Eskimos,

or we

may be unable to see the many silent

dimensions of this well-run White school.

1 The word “Indians” includes many distinct cultural

groups; sometimes I will use it to include Eskimos as well, particularly when

speaking of experiences all these groups share.

2 Estelle Fuchs and Dr. Havighurst have just

published a comprehensive report on the study, To Live on This Earth. American

Indian Education, New York: Doubleday. Copies of regional reports and final

reports presented to the U.S. Office of Education are available from ERIC (Educational

Resources Information Center, Bureau of Research, U.S. Office of Education).