|

Study of Alaska Rural Systemic Reform Final Report

James W.

Kushman

Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory

Ray Barnhardt

University of Alaska Fairbanks

with contributions

by other case study authors

October 1999

This research was supported by funds from the National Institute

on Education of At-Risk Students, Office of Educational Research

& Improvement, U.S. Department of Education. The opinions and

points of view expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect

the position of the funder and no official endorsement should be

inferred.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research involved the work of a learning community of more

than 30 university and laboratory researchers and community

researchers from seven rural Alaska communities, as listed

below-these different voices and perspectives enriched our case

studies.

Aniak/Kalskag (Kuspuk School District)

Bruce Miller; Senior Researcher, Northwest Regional Educational

Laboratory

Polossa Evans; Teacher Aide/Upriver Secretary, Lower Kalskag

Samantha John; Community Member, Aniak

Stan Lujan; Assistant to the Superintendent, Kuspuk SD

Bertha Passamika; Library Aide, Aniak

Mike Savage; School Board Member, Lower Kalskag

Klawock (Klawock City School District)

Jim Kushman; Senior Researcher, Northwest

Regional Educational Laboratory

Donna Jackson; Community Member, Klawock

Ann James; Teacher, Klawock

Rob Steward; School Counselor, Klawock

Koyukuk (Yukon-Koyukuk School District)

Beth Leonard; Senior Researcher, University of Alaska

Fairbanks

Tim dine; District Office, Yukon-Koyukuk SD

Sarah Dayton; School Staff/Community Member, Koyukuk

Charles Esmailka, District Office, Yukon-Koyukuk SD

Heidi Imhof; Teacher, Koyukuk

New Stuyahok (Southwest Region School District)

Jerry Lipka; Senior Researcher, University of Alaska Fairbanks

Natalia Bond; Secretary, New Stuyahok

Margie Hastings; Teacher, New Stuyahok

Ron Mebius; Principal, New Stuyahok

Quinhagak (Lower Kuskokwim School District)

Carol Barnhardt; Senior Researcher, University of Alaska

Fairbanks

John Mark; Principal, Quinhagak

Susan Murphy; District Office, Lower Kuskokwim SD

Nita Rearden; Language Development Specialist, Bethel

Dora Strunk; Teacher, Quinhagak

Tatitlek (Chugach School District)

Sarah Landis; Senior Researcher, Northwest Regional Educational

Laboratory

Joan Shaughnessy, Senior Researcher, Northwest

Regional Educational Laboratory

Anna Gregorieff; Community Member, Tatitlek

Dennis Moore; Head Teacher, Tatitlek

Roger Sampson; Superintendent Chugach SD

Tuluksak (Yupiit School District)

Oscar Kawagley; Senior Researcher, University of Alaska

Fairbanks

Ray Barnhardt; Senior Researcher, University of Alaska

Fairbanks

Freda Alexie; Bilingual Aide, Tuluksak

Sarah Owen; School Secretary, Tuluksak

John Weise; Superintendent Yupiit SD

We would like to thank Robert E. Blum, Program Director for

NWREL's School Improvement Program, for his support and help as

project director and his relentless pursuit of educational

excellence.

Kelly Tonsmiere and Roxy Kohler of the Alaska Staff Development

Network provided invaluable assistance in organizing events to bring

our community of learners and researchers together to plan and

analyze data. Christine Crooks performed a wonderful job of capturing

the sights and sounds of several case study communities through the

production of several videos.

Sue Mitchell of Inkworks provided the needed editorial assistance

as did members of NWREL's School Improvement Program support team,

including Meg Waters and Linda Gipe. We thank Denise Crabtree and Sue

Mitchell for cover design.

From the National Institute of Education of At-Risk Students, we

are grateful to Beth Fine and Karen Suagee for their help, support,

and personal interest in this study.

Finally, we are forever grateful to the educators and community

members who allowed us access to their communities so that all Alaska

educators can better understand how to create educational success for

rural Alaska students.

Jim Kushman

Ray Barnhardt

C0-Principal Investigators

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Contents

Executive Summary

Chapter 1. A Long Journey Begins at Home

A Brief History of Educational Reform in Rural Alaska

Alaska Case Studies

Participatory Research Methods

Alaska Onward to Excellence

Community Voice

Organization of This Report

Chapter 2. Case Study Executive Summaries

Kuinerrarmiut Elitnaurviat: The School of the People of

Quinhagak

Closing the Gap: Education and Change in New Stuyahok

A Long Journey: Alaska Onward to Excellence in Yupiit Tuluksak

Schools

Community Voice and Educational Change: Aniak and Kalskag

Villages

Creating a Strong, Healthy Community: Ella B. Vemetti School,

Koyukuk

Making School Work in a Changing World: Tatitlek Community

School

It Takes More Than Good Intentions to Build a Partnership: Klawock

City Schools

Chapter 3. Cross-Case Findings and Conclusions

Sustaining Reform

Shared Leadership

Building Relationships and Trust

Enacting New Roles

Creating Coherent Reforms

Creating Healthy Communities

Chapter 4. Recommendations

References

Report Released on Alaska Rural Systemic

Reform in Education

Ray Barnhardt, UAF

Jim Kushman, NWREL

Oscar Kawagley, UAF

Beth Leonard, UAF

Carol Barnhardt, UAF

Jerry Lipka, UAF

Sarah Landis, NWREL

Bruce Miller, NWREL

Seven Community Research Teams

[Following is the "Executive Summary" of

the final report from a three-year study of rural school reform

conducted by the NW Regional Educational Lab and UAF, in cooperation

with seven rural communities and school districts in Alaska. Copies

of the full report may be obtained from the NWREL, or from the Center

for Cross-Cultural Studies at UAF.]

This report presents the results of a three-year

study of educational reform in rural Alaska communities and schools.

The research revolves around seven case studies in villages and

school districts spanning western, central, and southeast Alaska.

These are primarily subsistence communities serving Eskimo and Indian

students. Each community had embarked on a reform process called

Alaska Onward to Excellence (AOTE) that strives to create educational

partnerships between schools and the communities they

serve.

The study examined how educational partnerships

are formed and sustained and how they ultimately benefit Alaska

Native students. Trying to understand the systemic nature of

educational change was a focal point of the study. In rural Alaska,

systemic change means fully integrating the indigenous knowledge

system and the formal education system. For rural school districts,

this means engaging communities deeply in education; fully

integrating Native culture, language, and ways of knowing into the

curriculum; and meeting Alaska's state-driven academic standards and

benchmarks-all at the same time.

Each case study was led by a researcher from the

Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory or University of Alaska

Fairbanks who worked with a small team of school practitioners and

community members who participated fully in the research. The case

studies tell what happened as rural schools embarked on a change

journey through AOTE and other reform activities, paying attention to

important educational accomplishments and setbacks, community voice,

and the experiences and learning of students. The cases include

qualitative and quantitative evidence, although hard data on student

performance was limited and often inappropriate to the educational

goals pursued by communities.

Through a cross-case analysis, six reform themes

and major findings emerged:

- Sustaining reform: It is easy to start

new reforms but difficult to keep up the momentum in order to

bring about deep changes in teaching and learning. Our case

studies show that sustaining serious educational reform over the

long run is a difficult but not impossible task in rural Alaska.

There were a variety of scenarios, including communities that

could not successfully launch an AOTE reform effort, those which

had many starts and stops on a long and winding road towards

important community goals, and at least one exceptional community

(Quinhagak) that has been able to create and sustain a Yup'ik

first-language program for more than a decade. The most

significant barrier to sustaining reforms is persistent teacher,

principal, and superintendent turnover. Turnover derails reform

efforts and leads to a cycle of reinventing school every two or

three years. A process like AOTE can help alleviate the turnover

problem by creating leadership within the community, especially

when respected community elders and other leaders are brought into

the process. But to seriously sustain reforms, districts and local

communities need to develop talent from within so that teachers

have strong roots in the communities where they teach.

- Shared leadership: Leadership needs to

be defined as shared decision making with the community

rather than seeking advice from the community. Strong and

consistent superintendent leadership was an important factor in

moving reforms forward in some of these small communities and

districts. However, school leaders must believe and act on the

principle of shared decision making in order to engage the

community through long term educational changes that benefit

students. Shared leadership creates the community ownership

that will move educational changes through frequent staff

turnover. School leaders must view a process like AOTE as a tool

for developing community engagement and leadership rather than a

school program that seeks the community's advice.

- Building relationships and trust:

Personal relationships and trust are at the heart of

successful reform, and processes like AOTE are only effective when

good relationships exist between school personnel and community

members. Strong relationships are based on a mutual caring for

children and cross-cultural understanding rather than a specific

reform agenda. In small communities, personal relationships are

more central than formal decision processes as the way to get

things done. A key teacher, principal, leadership team member,

parent, or elder who is highly respected in the community can

spark the change process. It is these respected people and their

relationships with others that help the whole community develop an

understanding of and connection to the principles of an external

reform model like AOTE. Too much emphasis can be placed on process

and procedure from the outside and not enough on building the

relationships and trust from the inside. Reformers in rural

settings might fare better if they worked to fully understand the

local context and build reforms from the inside out rather than

relying solely on external reform models.

- Enacting new roles: Educators and

community members are often stuck in old roles while educational

partnerships require new behaviors and ways of thinking. While it

is easy to talk about creating partnerships, changing traditional

roles is a learning process for both school personnel and parents.

The mindset that parent and teacher domains are

separate-and should remain so-hampers family

involvement efforts. Our case studies reveal that without a

compelling goal deeply rooted in community values, like preserving

language and cultural knowledge, many parents and community

members are content to leave education to the educators. Yet in

small rural settings, there are many avenues for parents, elders,

and other community members to be involved in school as

volunteers, teacher aides, other paid workers, and leadership team

members. Rural schools need to create a range of parent

involvement strategies appropriate for small communities.

Historical divisions between school personnel and Alaska Native

parents still need to be overcome. A partnership process like AOTE

must strive to rekindle the spirit of a people who feel

marginalized by the education system rather than part of

it.

- Creating coherent reforms: Small rural

communities and school districts need help in sorting through many

ongoing reforms in order to create a more unified approach to

educational and community change. There are many independent

reform activities in these communities with few connections. AOTE

was a positive force in most communities because it helped set a

clear direction and vision for student success and provided

opportunities for school personnel and community members to think

about and talk about how everyone should work together to educate

children in a changing world. AOTE was less successful as a force

for substantially changing teaching and learning. Here there was

often confusion or lethargy about taking action because there were

already so many educational programs in place. How AOTE fit into

this picture was unclear to participants. In rural Alaska, there

is a boom or bust cycle of programs related to curriculum,

instruction, assessment, and technology. Yet some cases showed

more unity of purpose and were able to progress towards reform

goals, make significant changes in educational practice, and see

students improve. These places often exhibited the enabling

characteristics described above including stability of school

leaders and teachers, shared decision making which empowers

communities while expecting improved student results, a climate of

trust and caring, and the ability to find the human and material

resources to achieve goals like bilingualism. Many elements have

to come together for classroom-level changes to occur, not the

least of which are creativity, hard work, and time.

- Creating healthy communities: Schools

in small rural communities cannot achieve their educational goals

in isolation from the well-being of the surrounding community. The

AOTE visioning process brought out the deeper hopes, dreams, and

fears of communities that are trying to preserve their identity

and ways of life in a global and technological world. AOTE

resulted in districts and communities challenging themselves to

simultaneously achieve high cultural standards and high academic

standards as a means to improved community health. People also

expect the education system to help young people respect their

elders, respect themselves, stay sober and drug free, and learn

self-discipline. There was a clear sense that education and

community health are inextricably linked. Education is viewed as

more than achieving specific academic standards and benchmarks.

While the desire is there to integrate Native knowledge and

Western schooling, educators in rural Alaska do not yet have all

the tools and know-how to achieve this end. More resources are

needed to create culturally-appropriate teacher resources.

Proposed funding cuts to Alaska's rural schools could threaten

further progress. Nevertheless, our case studies offer many

positive examples of bicultural and bilingual education that can

create more holistic and healthy communities in rural Alaska, with

the added benefit of improved student achievement.

The following recommendations are offered to

educators and policy makers based on the study. While directed to the

Alaska audience, these recommendations apply in large part to rural

schools and communities anywhere in the country.

- Stabilize professional staff in rural

schools.

- Provide role models and support for creating a

positive self-image to which students can aspire.

- Parent involvement needs to be treated as a

partnership with more shared decision making.

- Implement teacher orientation, mentoring, and

induction programs in rural schools.

- Eliminate testing requirements that interfere

with language immersion programs.

- Strategic planning needs to extend to the next

generation or more (20-plus years) at the state and local

levels.

- Strengthen curriculum support for culturally

responsive, place-based approaches that integrate local and global

academic and practical learning.

- Encourage the development of multiple paths

for students to meet the state standards.

- Extend the cultural standards and Native ways

of knowing and teaching into teacher preparation

programs.

- Sustainable reform needs to be a bottom up

rather than a top down process and has to have a purpose beyond

reform for reform's sake.

- Alaska Onward to Excellence (AOTE) should be

put forward as a means (process) rather than an end in itself

(program).

- Form a coalition of organizations to sponsor

an annual conference on rural education that keeps reform issues

up to date and forward reaching.

These findings and recommendations are discussed

more thoroughly in the body of the report.

CHAPTER 1

A LONG JOURNEY BEGINS AT

HOME

This report presents a study of educational reform in rural Alaska

Native communities. Researchers from the Northwest Regional

Educational Laboratory and the University of Alaska Fairbanks

collaborated on a three-year study of Alaska communities and schools

that were involved in varying reform efforts, including Alaska Onward

to Excellence (AOTE). This final report presents the major study

findings and recommendations. It is intended for educators and

policymakers in Alaska and other regions of the country who serve

rural, indigenous communities. Accompanying this report are the seven

case studies, which provide the qualitative and quantitative database

on which conclusions and recommendations are based.

Rural Alaska Native communities face new educational challenges.

Monetary support for rural schools is eroding within Alaska while

reformers everywhere are calling for higher academic standards. Low

test scores, harsh teaching conditions, and poor community health

are, unfortunately, what sticks in many people's minds when they

think of education in the Alaska bush. Certainly there are

educational problems, but the underlying issues are not well

understood. We do know that part of the problem is a dissonance

between two complex systems for educating Alaska Native students: the

indigenous knowledge rooted in Alaska Native culture, language, and

traditions and the formal education system designed by others to

serve rural Alaska (Barnhardt & Kawagley, 1998; Kawagley &

Barnhardt, 1999; Lipka, 1998). Research is needed to help us better

understand how to bridge this gap and create a more congruent

educational system.

A Brief History of Educational Reform in Rural

Alaska

By most indicators, the maturity level of the formal education

system in Alaska is at the adolescent stage. The constantly shifting

array of legislative and regulatory policies impacting schools make

it clear that they are still in an evolving, emergent state that is

far from equilibrium. This is especially true in rural Alaska, where

the chronic disparities in academic performance, ongoing dissonance

between school and community, and yearly turnover of personnel place

the educational systems in a constant state of uncertainty and

reconstruction. Schools are still struggling to form an identity and

role for themselves as they relate to the educational needs of rural

communities.

The continuous search for new personnel, each with their own

externally derived strategy for educational reform, leaves the

educational system vulnerable to a never-ending cycle of buzzword

solutions to complex problems. Each is tried for a year or two

without any cumulative beneficial effect, only to start the process

over again as personnel rotate through the districts, taking the

institutional memory with them. Within the last decade alone, rural

education in one corner of the state or another has been subjected to

variations on mastery learning, Madeline Hunter techniques,

outcome-based education, total quality learning, site-based

management, strategic planning, and many other imported quick fixes

to long-standing endemic problems, right up to the current emphasis

on "standards." The short-term lifespan of these well-intentioned but

poorly thought through and ill-fated responses to rural school

problems has only added more confusion and turmoil to a system that

is already teetering on the edge of chaos.

From a systemic school reform perspective, however, there are

advantages to working with systems that are operating "at the edge of

chaos," in that they are more receptive and susceptible to innovation

and change as they seek equilibrium and order in their functioning

(Waldrop, 1994). Such is the case for many of the educational systems

in rural Alaska, for historical as well as unique contextual reasons,

and it is to understanding the dynamics of systemic reform in such a

context that the rural Alaska case studies are directed.

By most any standards, nearly all of the 586,000 square miles and

245 communities that make up the state of Alaska would be classified

as "rural." Approximately 40% of the 600,000+ people living in Alaska

are spread out in 240 small, isolated communities ranging in size

from 25 to 5,000, with the remaining 60% concentrated in a handful of

"urban" centers. Anchorage, with approximately 50% of the

total population, is the only potential metropolitan area in the

state. Of the rural communities, over 200 are remote, predominantly

Native (Aleut, Eskimo, and Indian)

villages in which 70% of the 90,000 Alaska Natives live. The vast

majority of the Native people in rural Alaska continue to rely on

subsistence hunting and fishing for a significant portion of their

livelihood, coupled with a slowly evolving cash-based economy. Few

permanent jobs exist in most communities. The percentage of people

living in "poverty" in rural communities in Alaska ranges from 15%

to 50%, with the average cash income under $20,000.

From the time of the arrival of the Russian fur traders in the

late 1700s up to the influx of miners in the early 1900s, the

relationship between most of the Native people of Alaska and

education in the form of schooling (which was reserved primarily for

the immigrant population at that time) may be characterized as two

mutually independent systems with little if any contact, as

illustrated by the following diagram:

Before the epidemics that wiped out over 60% of the Alaska

Native population in the early part of the 20th century, most Native

people continued to live a traditional self-sufficient lifestyle with

only limited contact with fur traders and missionaries (Napoleon,

1991). The oldest of the Native elders of today grew up in that

traditional cultural environment, and they still retain the deep

knowledge and high language that they acquired during their early

childhood years. They are also the first generation to have

experienced significant exposure to schooling, many of them having

been orphaned as a result of the epidemics. Schooling, however, was

strictly a one-way process at that time, mostly in distant boarding

schools, with the main purpose being to assimilate Native people into

Western society. The missionaries and school teachers were often one

and the same. Given the total disregard (and often derogatory

attitude) toward the indigenous knowledge and belief systems in the

Native communities, the relationship between the two systems was

limited to a one-way flow of communication and interaction up through

the 1950s, and thus can be characterized as follows:

By the early 1 960s, elementary schools had been established in

most Native communities, administered by either the federal Bureau of

Indian Affairs or the Alaska State-Operated School System, both

centrally administered systems with the primary goal of bringing

Alaska Natives into mainstream society. The history of inadequate

performance by the two school systems, however, coupled with the

ascendant economic and political power of Alaska Natives, led to the

dissolution of the centralized systems in the mid-1970s and the

establishment of 21 locally controlled regional school districts to

take over the responsibility of providing education in rural

communities. That placed the rural school systems serving Native

communities under local political control for the first time, while

concurrently a new system of secondary education was established that

students could access in their home community. A class-action lawsuit

brought against the State of Alaska on behalf of rural Alaska Native

secondary students led to the creation of 126 village high schools to

serve those rural communities where before, high school students had

to leave home to attend boarding schools.

These two steps, along with the development of bilingual and

bicultural education programs under state and federal funding and the

influx of a limited number of Native teachers, opened the doors for

the beginning of two-way interaction between the schools and the

Native communities they served, as illustrated by the following

diagram depicting rural education in the mid-1990s (when the current

round of systemic reform initiatives were initiated):

Although the creation of the regional school districts (along with

several single-site and borough districts) and the village high

schools had provided rural communities with an opportunity to

exercise a greater degree of operational control over the educational

systems operating in rural Alaska, it did not lead to any appreciable

change in what is taught and how it is taught in those systems. The

continuing inability of schools to be effectively integrated into the

fabric of many rural communities after over 20 years of local control

pointed to the critical need for a broad-based systemic approach to

addressing educational conditions in rural Alaska.

Despite the structural and political reforms that took place in

the 1970s and 1980s, rural schools have continued to produce a dismal

performance record by most any measure. Native communities continue

to experience significant social, cultural, and educational problems,

with most indicators placing communities and schools in rural Alaska

at the bottom of the scale nationally. While there has been some

limited representation of local cultural elements in the schools

(e.g., story-telling, basket-making, sled-building, songs and

dances), it has been at a fairly superficial level with only token

consideration given to the significance of those elements as integral

parts of a larger complex adaptive cultural system that continues to

imbue people's lives with purpose and meaning outside the school

setting. Though there has been some minimum level of interaction

between the two systems, functionally they have remained worlds

apart, with the professional staff overwhelmingly non-Native (94%

statewide) and with a turnover rate averaging 30 to 40% annually.

These disparities and discontinuities were evident to the Native

leadership within a few years of having gained local control of their

schools, as indicated by the following observations of Eben Hopson,

mayor of the North Slope Borough, which had taken over its school

system in the early 1970s:

Today, we have control over our educational system. We

must now begin to assess whether or not our school system is truly

becoming an Inupiat school system, reflecting Inupiat educational

philosophies, or, are we in fact only theoretically exercising

"political control" over an educational system that continues to

transmit white urban culture? Political control over our schools

must include "professional control" as well, if our academic

institutions are to become an Inupiat school system able to

transmit our Inupiat traditional values and ideals. (1977)

In 1994, the Alaska Natives Commission, a federal/state task force

that had been established to conduct a comprehensive review of

programs and policies impacting Native people, released a report

calling for Alaska Native people to be more directly involved in all

matters impacting their lives and communities, including education.

The long history of failure of external efforts to manage the lives

and needs of Native people made it clear that outside interventions

were not the solution to the problems and that Native communities

themselves would have to shoulder a major share of the responsibility

for carving out a new future. At the same time, existing government

policies and programs would need to relinquish control and provide

latitude and support for Native people to address the issues in their

own way, including the opportunity to learn from their mistakes

(Alaska Federation of Natives, 1994).

With these considerations in mind, recent rural education reform

initiatives have sought to increase communication and bridge the gap

between the formal education systems and the indigenous communities

in which they are situated. In so doing, current reform initiatives

are seeking to bring the two systems together in a manner that

promotes a synergistic relationship. In such a relationship, the two

previously separate systems join to form a more comprehensive

holistic system that can better serve all students, not just Alaska

Natives, while at the same time preserving the essential integrity of

each component of the larger overlapping system. The new

interconnected, interdependent, integrated system that educational

reformers are seeking to achieve today may be depicted as

follows:

Forging a Renewed System of Education for Rural

Alaska

Manuel Gomez (1977), in his analysis of the notion of systemic

change in education, has indicated that "educational reform is

essentially a cultural transformation process that requires

organizational learning to occur: changing teachers is necessary, but

not sufficient. Changing the organizational culture of the school or

district is also necessary." This statement applies to both the

formal education system and the indigenous knowledge systems in rural

Alaska. To achieve the kind of "systemic integration" outlined above,

the culture of the education system as reflected in rural schools

must undergo radical change to become more accessible to the

community, while at the same time the indigenous knowledge systems

need to be documented, articulated, and validated in new ways if the

local culture is to become a significant part of the school

curriculum (Kawagley & Barnhardt, 1999; Lipka, Mohatt, &

Ciulistet, 1998). The challenge for reform advocates is to identify

the units of change that will produce the most results with the least

effort by targeting the elements of the system that can serve as the

catalysts around which the emergent order of a new system can

coalesce (Peck & Carr, 1997). Once these critical agents of

change have been appropriately identified, a "gentle nudge" in the

right places can produce powerful changes throughout the system

(Jones, 1994).

In response to these challenges, three major systemic reform

efforts are currently underway in rural schools throughout Alaska,

each with the goal of improving educational performance, but each

with strategies that engage the reform process in different ways. The

focus of the case studies that follow is on the evolution and impact

of the first of the three initiatives to be implemented-Alaska Onward

to Excellence (AOTE). The critical catalyst for reform embedded in

the AOTE planning process has been engaging the community as a key

player in shaping and monitoring the direction of the education

system. This is evident from the rationale outlined by Tonsmeire in

the original proposal to implement Onward to Excellence in rural

Alaska:

In this proposal we will outline a comprehensive,

collaborative, integrated effort to use what works to help Alaskan

educators assist rural, at risk children and youth in overcoming

the barriers to high performance. This effort will focus on

strategies to improve student performance in consideration of the

context in which at risk children live and from which they come to

school. Solutions that work for poor, minority children can and

are found not in the school alone, but in the interactions among

the school, the child, and the home. Therefore, we know this

effort must draw upon, not ignore, the social, cultural, and

economic context of home and community. (Tonsmeire, 1991)

From its inception, AOTE has been envisioned as a bottom-up

systemic reform process aimed at building community ownership in what

occurs in the educational system.

The second major systemic reform initiative to have a significant

impact on schooling in rural Alaska -

the Alaska Quality Schools Initiative (AQSI)- had its origins

as an Alaskanized version of a national school reform effort, driven

by the establishment of content standards, coupled with a

legislatively mandated accountability system involving qualifying and

benchmark exams for students, performance standards for professional

staff, and accreditation standards and report cards for schools. The

Alaska version of Goals 2000 has also placed an emphasis on parent,

family, business and community involvement. Although the AQSI started

out through the Alaska Department of Education as a carrot-based

reform strategy with voluntary participation, it soon evolved into a

stick-based approach as the political winds that were generated under

the banner of "accountability" blew across the Alaska educational

landscape. Under the new mandates, the diversity of individual,

community, and cultural needs in rural Alaska tend to have little

room for expression in the push for standardization through "a

results-based system of school accountability" (Alaska Department of

Education, 1998).

While the Alaska Onward to Excellence strategy has been focused on

promoting community participation in defining educational priorities

at the local level, and the Alaska Quality Schools Initiative has

emphasized mandating standards for accountability from the state and

national levels, the third systemic reform initiative

- the Alaska Rural Systemic

Initiative (AKRSI) - has pursued

a strategy of engaging all levels in a coordinated effort aimed at

systemic integration between the formal education system and the

indigenous knowledge system of the community (Kawagley, 1995).

The key catalyst for change around which the ALKRSI educational

reform strategy has been constructed has been the "Alaska Standards

for Culturally Responsive Schools," developed by Alaska Native

educators working in the formal education system coupled with the

Native elders as the culture-bearers for the indigenous knowledge

system (Assembly of Alaska Native Educators, 1998). From these

standards has grown an emphasis on "pedagogy of place," in which

traditional ways of knowing and teaching are used to engage students

in academic learning by building on the surrounding physical and

cultural environment. Included in this process have been initiatives

that engage students in learning through Native science camps and

fairs, cultural atlases, place name maps, family histories, language

immersion programs, subsistence activities, survival training, oral

histories, elders-in-residence, etc. In addition, educators at the

state and local level have been developing curriculum units,

performance standards, and assessment measures that demonstrate the

efficacy of integrating local materials and activities in the

educational process. The role of the Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative

has been to guide these initiatives through an ongoing array of

locally generated, self-organizing activities that produce the

"organizational learning" needed to move toward a new form of

educational system for rural Alaska.

While each of the three systemic reform strategies outlined above

has strengths and limitations, together they reflect a powerful array

of initiatives that cut across all facets of the educational

landscape in rural Alaska, from strategic planning and goalsetting

(AOTE), to curriculum development and teaching practices (AKRSI), to

establishing standards, assessments and incentives for high

performance (AQSI). The case studies that follow, though focused on

Alaska Onward to Excellence, will provide insights on the process of

systemic reform for rural schools in general. It is incumbent on

Alaska educators to look deeply within themselves and the communities

they serve to find ways of creating partnerships to help Alaska

Native students succeed in two worlds. As one participant in the AOTE

process put it as the magnitude of the challenge became evident: "A

long journey begins at home."

Alaska Case Studies

This research involved case studies of seven rural Alaska

communities that have implemented Alaska Onward to Excellence. The

case studies center around several broad research questions:

- Can schools and communities successfully work together to

achieve common goals for rural Alaska Native students? What are

the essential elements of this partnership? What factors promote

the partnership and what barriers stand in the way? What sustains

the partnership over time? How does a process like AOTE contribute

to such partnerships?

- Does a partnership between school and community lead to real

benefits for students? Under what conditions do the experiences

and learning of students change for the better?

- What lessons can we learn from these case studies to guide

future improvement efforts in rural Alaska or other similar

communities across the country? What are the larger implications

for Alaska Native and Native American education?

The seven communities we studied span western, central, and

southeast Alaska and range in size from approximately 125 to 750

residents. While all of these communities participated in the AOTE

process, they were quite diverse in demographics, community context,

and history of school reform. The case study summaries in this report

(and the full case studies) provide a richer description of each

community. The seven village or small-town sites are listed below.

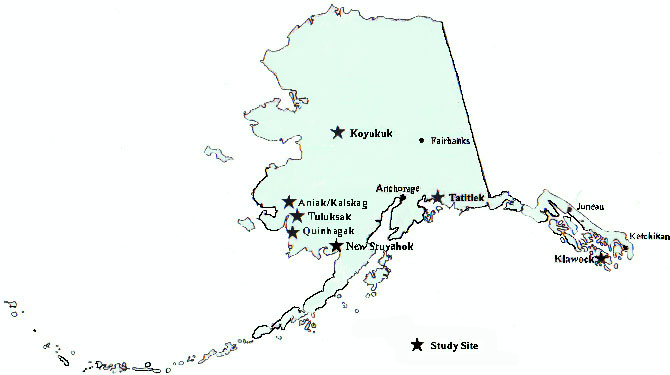

Figure 1 shows their locations.

- Quinhagak in the

Lower Kuskokwim School District, on the Kuskokwim Bay

- New Stuyahok in the Southwest Region School District,

northeast of Bristol Bay and Dillingham.

- Tuluksak in the Yupiit School District, northeast of

Bethel on the Lower Kuskokwim River

- Aniak and Kalskag (treated as a single case

study of neighboring villages) in the Kuspuk School District,

northeast of Bethel

- Koyukuk in the Yukon-Koyukuk School District, well west

of Fairbanks on the Yukon River

- Tat itlek in the Chugach School District, on Prince

William Sound near Valdez

- Klawock, a single-site school district (Klawock City

Schools) on Prince of Wales Island, far southeastern Alaska near

Ketchikan

Figure 1

Case Study Sites

These communities are small isolated villages or towns reached by

small airplane. Their schools, which can serve as few as 20 or as

many as 200 students in grades K-12, come under the supervision of

separate school districts in a system of Regional Educational

Attendance Areas (REAA). Each REAA-some of which are as large as

medium-sized states in the "Lower 48"-has the responsibility of

educating children in their area. While there are state guidelines,

each REAA has its own elected school board and has some latitude in

designing a school system that makes sense for its region.

Superintendents and school boards set policy and procedures, hire

staff, establish budgets, choose curriculum, and make other important

decisions that affect schooling in these small communities.

In rural village schools, students are typically educated in one

or two prefabricated school buildings (including a high school and a

gymnasium) and often in multigrade classrooms. Instruction in the

early years may be in a Native language (such as Yup'ik) and most

schools today try to incorporate at least some Alaska Native cultural

components into the curriculum. While teachers often come from the

outside, community members serve as classroom and bilingual aides

(Bamhardt, 1994).

Sports such as boys basketball and girls volleyball are an

important part of school life, providing students with opportunities

to travel to other villages and to large cities like Anchorage. Field

trips, career fairs, and state academic decathlons are other ways

that educational opportunities are expanded beyond the village. But

most communities are subsistence villages, so that education also

happens around important activities like hunting and fishing trips,

during which time students may leave school for several days or more.

Education also happens around important village events like

potlatches, which feature traditional Native dance and stories. More

and more, elders and other community members can be seen at schools

as teachers of language, culture, and values. In short, efforts are

being made to meld Western education and traditional village

education, but this is often a struggle because of historical

misunderstandings and mistrust between different cultures, languages,

and ways of educating.

We have tried to capitalize on the diversity of the seven sites

through a case study approach. Each case study is an important story

in its own right, documenting both the successes and shortcomings of

ongoing reform efforts, that has meaning to the people of

this community and other similar communities both inside and

outside of Alaska. We also conducted a cross-case analysis to shed

light on the deeper issues of systemic change and identify school

improvement mechanisms and processes that may generalize beyond

individual communities.

Participatory Research Methods

Researchers, school personnel, and community members collaborated

on this study mirroring the very partnership process we were trying

to understand. We used a participatory action research approach that

treats school practitioners and community members as co-researchers

rather than "subjects" of study (Argyris & Schon, 1991). Too

often, research has been conducted on rather than with

Alaska Native people, based on external frameworks and paradigms

that do not recognize the issues, research questions, and worldviews

of those under study. For each community, a senior researcher from

the Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory or University of Alaska

Fairbanks led a small team of three to five school and community

researchers who helped plan each case study, formulate guiding

questions, collect data, and interpret results. A typical team

consisted of a school district practitioner, a village school

practitioner, at least one non-school community member, and in some

cases a high-school student. The teams included both Alaska Natives

and non-Natives who lived in the communities under study. This team

composition resulted in a greater awareness of what happens daily in

schools and communities, access to others who served as key

informants, and a deeper understanding of history, culture, and

relationships present in each community

The teams used traditional case study methods, including document

analysis, participant and researcher observation, and surveys and

interviews. Concept mapping was also used to more fully understand

the many simultaneous reforms happening in these communities. We

followed a pattern of collecting data via site visits and then

meeting in a central Alaska location to share and discuss results.

Each senior researcher spent approximately 10 to 12 days on site

during three or four separate visits across two school years. Most of

the community teams, with guidance from their senior researcher, also

collected some data on their own in the form of participant

observation, formal

surveys, and interviews. We met in Anchorage six times (12 days)

to work in small village teams and as a whole group to discuss and

interpret results, design data collection techniques, and plan the

next data collection steps. Senior researchers met together an

additional four times (8 days) to plan the study and outline and

write up findings. In this way, we refined the research questions and

data collection as we engaged together in constant-comparative

analysis.

Alaska Onward to Excellence

While the seven sites were quite diverse in their make-up and

histories of school reform, what they shared in common was a

district-initiated reform process called Alaska Onward to Excellence.

In AOTE, school districts and village schools work closely with

community stakeholders (parents, elders, other community members, and

students) to establish a mission and student learning outcomes.

Working through multi-stakeholder leadership teams, AOTE attempts to

develop a school-community partnership and action plans to achieve

these outcomes. This educational partnership was a focal point of our

case studies.

Through a foundation grant from the Meyer Memorial Trust, the

Alaska Staff Development Network and the Northwest Regional

Educational Laboratory (NWREL) began designing the Alaska Onward to

Excellence process in 1991. The vision of AOTE was to bring

research-based practices to rural Alaska schools through a process

that deeply involved the whole community in a district and school

improvement process. AOTE, working simultaneously at the district and

community school levels, tries to achieve four reform principles:

- Focus on student learning. AOTE begins with the belief

that all students can learn and strives for equity and excellence

in student learning. To achieve agreement on what students need to

learn, the first step is direction setting, which results in a

mission and student learning goals developed with broad input from

parents, village elders, students, and school staff. A district

mission and goals are developed with village input; village

improvement teams then design action steps to achieve at least one

district goal.

- Everyone must be committed. Community and schools share

leadership for the improvement process through multi-stakeholder

district and village leadership teams. The expectation is that

parents and other community members are full partners in education

and that schools and communities must work together to achieve

student success. The district role is to support and monitor

school improvement efforts at the community level.

- Everyone will learn together. Improvement equals

learning for both adults and students. Before a mission and goals

are set and before action plans are made, learning takes place so

that decisions are informed by local culture and values as well as

research-based practices.

- Learning success will be measured. Learning is supposed

to be monitored in goal areas. In most goal areas (such as student

fluency in both English and Yup'ik), this requires moving beyond

typical standardized test results.

The AOTE process was first implemented in two rural Alaska

districts in 1992-95 (Phase 1). Implementation was achieved through a

series of on-site workshops led by the two NWREL developers of AOTE

(Robert Blum and Thomas Olson) for district and village leadership

teams. Additional technical assistance was also provided as needed.

In 1995-97 (Phase 2), AOTE was expanded to three new districts

with funds from a Goals 2000 Implementation Grant and a grant from

the U.S. Department of Education Urban and Rural Reform Initiative.

This new phase not only expanded the number of schools, but used a

training-of-facilitators approach: each district and village sent

small facilitator teams to Anchorage for training by the NWREL

developers/trainers. Facilitators, in turn, trained and guided the

work of local district and village leadership teams back in their

districts and villages. In addition to leadership teams, a district

research team was also formed and trained by NWREL to collect data

that would help the leadership teams monitor progress towards their

improvement goals. Finally, the Phase 3 expansion in 1996-98 followed

the same training model as Phase 2, except that cotrainers from the

Alaska Regional Assistance Center worked with the NWREL team to

provide the facilitator and research team workshops and follow-up

technical assistance.

The three phases together resulted in training and implementation

of AOTE in 11 districts and 42 community schools.

The seven case study communities (in seven different districts)

were strategically selected from all three phases of AOTE. Two Phase

1 sites-New Stuyahok in the Southwest Region School District and

Tuluksak in the Yupiit School District-provided a look at

sustainability of AOTE-led reforms over time. Three Phase

2 sites-Quinhagak in the Lower

Kuskokwim School District, Koyukuk in the Yukon-Koyukuk School

District, and Tatitlek in the Chugach School District-provided a look

at the early stages of partnership and how action plans were carried

out. Finally, two Phase 3 sites- Aniak[Kalskag in the Kuspuk

School District and Klawock in the Klawock City School District-were

intended to illustrate how school-community partnerships are formed

during the start up of AOTE.

While AOTE was a focal point for school reform in all of these

communities, it was by no means the only reform. As discussed

earlier, there are currently two other major systemic reform efforts

in Alaska. Many of the sites were also participating in the Alaska

Rural Systemic Initiative, which is attempting to integrate

indigenous knowledge and curriculum into the formal educational

system. Increasingly, all Alaska districts and schools face new

requirements from the state's Alaska Quality Schools Initiative,

which stresses high learning standards and a new high-school

graduation exit exam. Our goal was not to neatly sort out the impact

of AOTE, a nearly impossible task anyway. Rather, we wanted to study

and understand how reform happens, how roles and relationships

change, how partnerships are sustained over time, and how AOTE adds

value to the larger reform process.

Community Voice

In trying to understand reform and AOTEE, our case studies focused

on a key variable we called community voice. Community voice

captures the essence of what we believe to be the important elements

of a productive educational partnership between schools and

communities in remote Alaska villages, whether or not they use AOTE.

Our definition of community voice included four components:

- shared decision making or the extent to which community

members (parents, elders, and others) have greater influence and

decision-making power in educational matters

- integration of culture and language or the extent to

which Native language, culture, ways of knowing, and a community's

sense of place are woven into daily curriculum and

instruction

- parent/community involvement in educating children or

the extent to which parents, elders, and others have a strong

presence and visibility in the school and otherwise participate in

their children's education

- partnership activities or positive examples of the

school and community working together to share responsibility for

student success

What we are really talking about is full community participation

and shared accountability. In our definition, educators need to be

willing to listen to the voice of the community and share some of the

decision-making power. A further validation of the community's voice

means that local heritage, language, culture, and Native ways of

knowing are legitimate parts of formal education and are viewed as

strengths to build a school curriculum on. We would also expect to

see parents and elders routinely involved in their children's

education if there was a true partnership. Finally, we were searching

for positive examples of school-community partnerships that will have

a pervasive impact on students and that other communities might

replicate. In simpler terms, community voice means connections

between schools, families, and communities to promote student

success. This concept is at the heart of AOTE and is likewise an

element of the Alaska Quality Schools Initiative.

Organization of This Report

A challenge in presenting the results of seven case

studies is the sheer volume of descriptive data and how to present it

in a readable manner for busy educators and policymakers. The

full "thick descriptions" are presented elsewhere in a set of

individually bound case studies. Chapter 2 of this report presents

case study executive summaries, each written by the senior researcher

who directed the study with his or her school/community team. Each

summary presents a brief description of the community and research

effort, followed by key findings and lessons learned about systemic

reform. The third chapter presents our major conclusions around six

reform themes. These themes and conclusions resulted from several

meetings with senior researchers and teams in which we all stepped

back from our own community findings and tried to draw out the larger

conclusions and lessons about educational reform in rural Alaska.

Finally, Chapter 4 presents our recommendations for educators and

policymakers, with a primary focus on the Alaska audience. However,

we believe that these recommendations are applicable in other regions

of the country serving similar populations.

CHAPTER 2

CASE STUDY EXECUTIVE

SUMMARIES

Case study executive summaries are presented in this chapter,

including major findings and lessons learned about systemic change.

The sites are presented in geographic order moving from southwestern

Alaska, which has the greatest concentration of sites, to the

interior and finally southeastern Alaska (see Figure 1 for site

location). It is impossible to capture all of the rich detail in

these summaries; readers interested in such detail can obtain the

full case studies.

Kuinerrarmiut Elitnaurviat:

The School of the People of Quinhagak

Carol Barnhardt

University of Alaska

Fairbanks

Quinhagak, a Yup'ik Eskimo community of 550 people, sits on

the southwest coast of Alaska close to where the Kanektok River flows

into the Bering Sea. It is a region of Alaska where Yup'ik people

have lived for thousands of years, and the name of the village,

Quinhagak, is derived from kuingnerraq, which denotes the

ever-changing course of the Kanektok as it regularly forms new

channels, winding its way through the surrounding tundra. Today, the

lifestyle of the people of Quinhagak continues to embody the name of

their community-as is evident in the evolving practices that provide

evidence of their ability to integrate the traditions and beliefs of

their Yup'ik ancestors with the contemporary practices necessary for

success in a rapidly changing modern world. Subsistence activities

that range from hunting seal and caribou to fishing and gathering

wild berries and greens are practiced; the Yup'ik language continues

to be used in home, social, political, and educational contexts; a

few residents continue to go to the river for their drinking water;

and some people use dog sled teams. However, Quinhagak people today

can also purchase all varieties of foods from their local store,

enroll in college coursework delivered to them through computer and

audio/video conferencing, watch television on nine different

channels, travel in and out of their remote village on five regularly

scheduled daily flights, and nearly all residents can communicate in

both Yup'ik and English.

Although this might appear to be a community of contradictions, it

is in fact a community where many residents are in the process of

finding a satisfying and workable balance between old and new,

traditional and contemporary, Western and non-Western ways of knowing

and living. It is a community that has continued to place a high

value and priority on the Yup'ik language, despite decades of

English-only influences. It is a community that is exercising its

tribal rights by assuming responsibilities previously delegated to

state and federal authorities. It is a community where people have

maintained their membership and participation in the Moravian church

while continuing to practice and follow many Yup'ik beliefs and

traditions. It is a community in which the daily lives of its

residents make it evident that they have been successful in finding

ways to integrate beliefs and practices that many people believe are

incompatible.

Kuinerrarmiut Elitnaurviat is the Yup'ik name of the school in

Quinhagak-a name chosen by the community in 1980. Roughly translated,

it means "the school of the people of Quinhagak." The name reflects

the community's belief in the importance of local ownership and

genuine involvement in the schooling process of its own children. In

the past few years, Quinhagak people have made a concerted effort to

initiate a range of programs in their 140-student, K-12 multigraded

school that will provide their children with the tools and resources

necessary to meaningfully integrate Yup'ik language, values, and

beliefs into school practices and policies. This will provide them

with the ability to be successful in meeting Yup'ik "life standards"

as well as preparing them to meet the academic standards of the state

of Alaska. The focus of the Quinhagak case study is on the efforts to

integrate community and school practices and policies, with a

description of the role that the Alaska Onward to Excellence (AOTE)

process has played in this reform effort.

Influences of the Past

For nearly 100 years, the modus operandi of federal and

state educational systems in Alaska was to ignore the history,

culture, and language of Alaska Native people, and it is clear that

even today the historical factors that helped to shape the social,

political, and educational context of Quinhagak continue to exert a

very direct influence. Although there has been a public elementary

school in Quinhagak since 1903, many people were not able to complete

more than a few years of schooling because of family responsibilities

or because there was no local schooling opportunity beyond sixth

grade. The first teachers in the Quinhagak School were associated

with either the Moravian Church or the Bureau of Indian Affairs

(BIA). Like most villages in this region, Quinhagak's school was

managed by the BIA until the extensive and far-reaching

decentralization, of Alaska's rural schools by the state legislature

in 1976. Following the decentralization Quinhagak became formally

associated with the Lower Kuskokwim School District (LKSD)- the

largest of the 24 newly established rural school districts in the

state of Alaska.

Research Methods

Members of the Quinhagak case study team included John Mark, a

member of the Quinhagak community and principal of Kuinerrarmiut

Elitnaurviat School; Dora Strunk, a member of the Quinhagak community

and elementary teacher at Kuinerrarmiut Elitnaurviat School; Nita

Rearden, a Yup'ik language coordinator in the Bilingual and

Curriculum Department of the Lower Kuskokwim School District; Susan

Murphy, Assistant to the Superintendent of the Lower Kuskokwim School

District; and myself. I served as a representative of the University

of Alaska Fairbanks and had the responsibility of preparing the case

study. Our team examined and reviewed community, school, and district

materials for the case study gathered during: my three visits to

Quinhagak; two visits to Bethel to meet with district personnel; and

five whole-team meetings in Anchorage. I also met formally and

informally with students, teachers, teachers aides and community

members during my Quinhagak visits, observed in all the

classrooms, and attended events that occurred during my visits

(e.g., a community-wide graduation ceremony for students in

kindergarten, eighth grade and twelfth grade- conducted almost

entirely in Yup'ik). Some of the team members communicated regularly

via e-mail. Three members were able to participate in state and

national conference presentations. All but one of the Alaska Native

certified teachers at Kuinerrarmiut Elitnaurviat received their

bachelor's degrees from UAF (and I had served as academic advisor for

four of these seven teachers). Two of the team members were enrolled

in UAF graduate courses during the project.

Major Findings

Connecting school and community is a primary goal of the Alaska

Onward to Excellence (AOTE) process, and because of the centrality of

this goal, the AOTE process found fertile ground when it was

initiated in Quinhagak in 1995. Based on our case study team's

initial review and then formal documentation of reform efforts in

Quinhagak, it quickly became evident that most of the significant

changes in the school in recent years were attempts to recognize and

meaningfully integrate what is important and valued in the life of

the community with the teaching and learning that occurs in school.

The educational goals of the community, as identified by past

practices and by the community-constructed AOTE plan and student

learning goal (i.e., "students will learn to communicate more

effectively in Yup'ik") advocate the use of what children already

know, value, and are interested in. This knowledge base should serve

as a solid foundation for academic growth and learning in all ten

Alaska academic content areas including reading and writing, math,

science, world languages, history, geography, government and

citizenship, technology, arts, and skills for a healthy life. In

Quinhagak the AOTE process reinforced and provided additional support

for long-established beliefs and practices about the importance of

merging school and community. The statements below provide evidence,

documented in the case study, that the school and the community are

merging in significant and multiple ways.

Evidence of Shared School/Community Values and

Priorities

in the Sights and Sounds of Kuinerrarmiut

Elitnaurviat

When one enters the front door of Kuinerrarmiut Elitnaurviat, the

sights and sounds make it immediately evident that this is not a

school like one in downtown Anchorage or in rural Arkansas. A large

banner high on the wall tells people "Ikayuqluta Elitnaulta"

(Let's Learn Together), a bulletin board has materials written in

Yup'ik and English, and there are photos of village elders in the

hallways. A display of photos of teachers and other staff members in

the school lets everyone know that the large majority of people who

work in this school, including nearly half of the certified teaching

staff, are Yup'ik people from the community. The principal, John

Mark, is a lifelong member of the Quinhagak community. The Daily

Bulletin, with all school news and information, is posted not

only on the school's bulletin board, but also in several community

locations because it is faxed daily to the IRA tribal office, the

clinic, and the store in an effort to keep community members aware of

school events and activities. The school library has large paintings

on the walls with scenes of the Quinhagak area, and an "Alaska and

Yup'ik Collection" that includes nearly every book that has been

published in the Yup'ik language.

Evidence of Shared School/Community Values and

Priorities in Curriculum and Pedagogy

Several of the most significant and pervasive responses to the

goals of melding school and community priorities, increasing student

learning, and communicating more effectively in Yup'ik are evident in

the implementation of new or modified Kuinerrarmiut Elitnaurviat

curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment, as summarized below:

- Daily interaction in the school is in both Yup'ik and English.

The language of instruction in kindergarten through third/fourth

grade is Yup'ik, and report cards for students in grades K through

4 are printed in Yup'ik. Students in upper grades receive daily

oral and written instruction in Yup'ik from the school's Yup'ik

Language Leader.

- The Lower Kuskokwim School District provides summer institutes

that support Yup'ik educators in preparing and producing of a wide

range of curriculum materials in the Yup'ik language. Many

materials are written and illustrated by Yup'ik educators.

- One of the primary considerations in selecting the new

comprehensive, balanced reading/literacy program by LKSD in the

1998 school year was the desire to adopt a program and approach

that would be appropriate for children who are striving for

proficiency in both Yup'ik and English literacy.

- An extensive effort to integrate Yup'ik ways of knowing and

Yup'ik belief systems across the K-12 curriculum and throughout

the entire district was initiated through the development and use

of Yup'ik thematic units that cover the entire academic school

year. This curriculum provides students with the opportunity to

gain knowledge and skills related to Yup'ik values, beliefs,

language, and lifestyles in grades K-12.

- In addition to enrolling in courses that meet all Alaska

high-school requirements (e.g., English, math, science, social

studies, physical education), high-school students in Quinhagak

also participate in courses in computer/journalism, workplace

basics, and wood I or II. In addition, each student is required by

the local Quinhagak Advisory School Board to enroll in the Yup'ik

Life Skills class (Kuingnerarmiut Yugtaat Elitnaurarkait) for two

years. This class includes Yup'ik language and culture, Yup'ik

orthography, and Yup'ik life skills.

Evidence of Shared School/Community Values in Choices

Made for Assessment Policies and Practices

The Lower Kuskokwim School District, recognizing the complexity

and challenge of valid assessment in schools that serve children from

bilingual backgrounds, has been one of the most aggressive in its

efforts to develop and use multiple types of assessments. The

district has supported Quinhagak and other sites in their efforts to

increase, and integrate within the curriculum, the use of assessments

that are authentic and performance-based and that allow for more than

one correct response.

As one of the pioneers in the state's effort to implement the

Writing Process, the Lower Kuskokwim School District developed a

Student Literacy Assessment Portfolio process that is directly

related to the state student academic content standards in English

and Language Arts. This process also supports the Yup'ik Language

Program. All students in Kuinerrarmiut Elitnaurviat have a literacy

portfolio, and most student's portfolios include papers and projects

in both Yup'ik and English.

There has been a steady increase in the norm-referenced

standardized test scores of students in rural Alaska school districts

over the past 10 years, including those in LKSD. In the past few

years, it has been determined that the CAT5 and Degrees of Reading

Power scores of 11th and 12th grade students in LKSD who have

attended Yup'ik First Language schools are-on the average-higher than

students who did not attend a YFL school.

Extracurricular academic assessment activities that Quinhagak

students participate in include school and district-wide speech

contests, and students can choose to compete in either Yup'ik or

English. A more diverse group of people (including school board

members, elders, AOTE team members and parents) is now becoming more

directly involved in the assessment process in Quinhagak and some

other LKSD sites, to help determine if students are reaching the

goals set by the community, the school, the district, and the

state.

Evidence of Increasing Opportunities for Family and

Community Participation

and Meaningful Involvement in the School

In addition to changing curriculum, pedagogy and assessment goals

and practices, Quinhagak is developing more incentives and

opportunities for increased family and community participation in the

education of their children.

- Many parents in Quinhagak are now directly involved in their

school because they are serving as the school's teachers, aides,

cooks, custodians-and principal.

- Several community members serve their school in other

positions. Those on the Advisory School Board deal with matters

ranging from setting the school calendar to approving changes in

the school's bilingual program and AOTE goals, helping establish

budget priorities, to annual approval of the school's principal.

The AOTE process also requires volunteer involvement of community

members on leadership teams, and AOTE provides the opportunity for

broader participation through its community-wide meetings and

potlucks. Other venues for direct participation include the

Village Wellness Committee Team and the Kuinerrarmiut Elitnaurviat

Discipline Committee.

- The Kuinerranniut Elitnaurviat Discipline Plan was drafted in

1997 by a discipline committee that included representatives of

the community, staff, and school. The proposed plan was reviewed

and approved by the Quinhagak Advisory School Board after a review

by school staff, parents, and students.

- Some family members participate in less formal ways through

volunteer work in their children's classroom or as chaperones on

trips. Others contribute through efforts in their own homes (e.g.,

providing a quiet place for children to study, reading with and to

children, reviewing homework assignments with them). In 1997, the

school identified 15 initiatives designed to promote increased

parent, family and community involvement and participation in the

school. There were 119 different volunteers and 1,500 hours of

volunteer service in 1997-98.

- School policies related to the use of the school building also

support a community and school partnership. The gymnasium often

serves as a central gathering place for several different types of

community functions (e.g., hosting a community potlatch, holding

local and regional basketball events, for proms and other dances,

and for celebrating students' graduation).

Summary Comments

This section provides observations and summary comments regarding

(a) factors that have contributed to the community of Quinhagak

making the choices it has for its school; (b) factors that have

enabled Kuinerrarmiut Elitnaurviat to implement new and

self-determined educational priorities; (c) challenges that people of

Quinhagak face in their efforts to narrow the gap between school and

community and to increase student academic achievement.

Factors that have contributed to Quinhagak's decision to use

Yup 'k as the language of instruction, develop and require a Yup'ik

Life Skills curriculum for high-school students, and provide

increased opportunities for parents and other community members to

participate in teaching and learning activities:

- The people of Quinhagak strongly believe in the importance of

their young people learning through and about Yup'ik values and

beliefs, as is evident in the mission statement in their AOTE

plan. The people of Quinhagak continue to use the Yup'ik language

as their primary language for communication.

- The people of Quinhagak have demonstrated an ability to assume

leadership positions at a local level. There is strong

confirmation of the community's commitment to self governance and

an interest and willingness to assume responsibility and control

in their village, as evidenced through their new tribal government

initiatives as well as in matters directly related to schooling

and to education.

- The people of Quinhagak have sufficient numbers of

Yup'ik-speaking certified teachers to implement their

community-set goals in their school.

- The opportunity to use and integrate their Yup'ik language and

culture is supported by their school district. LKSD is the only

district in the state that provides its local sites with the

option to choose what type of bilingual program it desires for its

children.

Factors that have enabled Kuinerrarmiut Elitnaurviat to

implement new, self-determined educational priorities:

- Quinhagak is one of only a few rural communities in the state

that has such a high percent of local, college-graduated,

certified teachers who speak the language of the community, and a

principal who is a member of the community.

- The AOTE process was initiated at a time when the community

was receptive and ready for a grassroots effort that allowed for

input and participation from a wider range of people than other

previous efforts. AOTE in Quinhagak was shaped by a larger and

more diverse group of people than some of the previous educational

plans, and it was a bottom-up effort, rather than a top-down

mandate.

- Kuinerrarmiut Elitnaurviat has been supported in its efforts

by the Lower Kuskokwim School District (through bilingual program

options, bilingual training for teachers and aides, preparation of

Yup'ik materials and Yup'ik-based theme curriculum, summer

institutions for Yup'ik curriculum development, hiring processes

that give priority to Yup'ik teachers when other qualifications

are equal, and strong and consistent career ladder development

programs).

- There are a now a number of current statewide systemic reform

efforts that complement and support many of Kuinerrarmiut