|

Cross-Cultural Issues in

Alaskan Education

Vol. I

RURAL SECONDARY EDUCATION:

SOME ALTERNATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

by

D.M. Murphy

Cross-cultural Education Development Program

Alaska State Department of Education

Anchorage, Alaska

Introduction

This presentation is a concept paper, not a statistical treatment

of school enrollment figures, costs, and logistics. The intent is to open

consideration

of a different approach to the delivery of secondary education in rural

areas through a process of assessing and identifying existing resources for

secondary

education in the State, developing a community-based and environmentally

oriented curriculum for grades nine and ten, then creating a sequence

throughout the

four-year program which would capitalize on the existing formal resources,

and the community and environment as an educational resource.

Among the

benefits of this approach are the effective utilization of existing facilities,

a substantially decreased cost of the building program, greater

involvement of the community in education, a more humanistic, experiential,

and relevant high school program and a focus on teacher education processes.

All these benefits would concurrently benefit the secondary school students

and even be in the best interests of children at the elementary level.

The

Problem

The pressures for providing secondary schooling on-site, at or near

the home communities of the rural children, is intense from all quarters,

legal, political,

and moral. Among the results of such pressures has been a new regulation1

which calls for the establishment of a secondary program in any community

in which

there is one or more secondary school-age persons and an elementary

school, unless the community opts not to have such a program. But the

new regulation

does not deal with program development processes, or provide insight

into available resources, or alternative systems. Yet it does specify

certain

conventional academic area minimum standards which, fortunately,

can be altered through

outlined procedures.

Also, at this writing, it appears likely that

a large scale high school building program will commence; but a

commitment of funds

for construction

doesn’t

suggest the nature of buildings best suited to fit the secondary

programs which are yet to be developed.

Further, concern for the

socio-economic impact of the new schools upon the communities is

only recently awakening, much less there

being solutions

on

the horizon. Community awareness and focus on the essential need

for creating constructive outlets for adolescent energies during

the majority

of their

waking hours, those spent not in school, may at this stage be of

greater importance

and consequence then the design of the formal school curriculum

itself. Consideration of new small high schools development without

concurrent

consideration

of how they will alter the social fabric of communities and families

risks serious consequences to all.

Resources and Premises

As a beginning, let us examine the secondary school

system from the perspective of educational resources which currently exist,

in order

to compare what

there is with what is needed. The difference will, of course,

imply the magnitude of the problem and will indicate the requirements

necessary to address it.

In order to not confuse the issue, the problem should not be

thought

of in terms of cost in dollars. Personnel, materials, buildings,

equipment, land,

and transportation costs are not of a programmatic nature and

should be

set aside momentarily to enable us to conceptualize and explore

unconventional alternatives.

For clarification, the term ‘rural’ in

the context of this examination means communities which are

isolated from each other and from the urban centers

by a lack of the normal means of surface transportation necessary

to provide for the movement of construction materials, supplies,

equipment, and people

at a cost reasonably near that of non-rural communities served

by highway, rail, or regular enroute marine transportation.

At one end of the rural spectrum

are towns such as Bethel, Nome, Kotzebue, Dillingham, and Metlakatla.

At the other end are villages such as Noorvik, Kongiganak,

Nondalton, Angoon, Chakyitsik,

and Allakaket.

The identification of resources traditionally

seen as being encompassed within an educational facility is a simple matter:

the teachers,

the texts, a gym,

the shops and labs, the libraries, music rooms, instruments,

and so forth. The identification of existing secondary school

facilities

is

the second

step and, again, can be readily done. It is known how many

rural and urban high

schools there are, their size and locations, and whether

they are day schools or boarding schools, local or regional. These

facts

enter into

the consideration

of a rural high school development plan, but should be dealt

with at a later stage since the existence of such schools

is only one

component

of

an

overall plan and must be dealt with in the context of total

needs.

For sake of simplicity, several premises should be

stated:

- The existing rural elementary school facilities are not

being fully or adequately utilized (evenings, summers,

etc.).

- All school age children and youth do not have to attend

school (or go through the educational process) during

the same hours

each day,

days each

week, or

weeks each year.

- Total time of exposure to formal educative

processes spent by a person does not, within certain limits, relate

directly

to educational

outcomes.

(That

is, there is no magic in 5 hours, 20 minutes per day

for 188 days, or any other figure. The reasons for

these teaching

times

and length

of

school

year are

based on other considerations having little to do with

concern for the student.)

- Increasing expenditures

on traditional educational practices is not likely to improve educational

outcomes

substantially.2

- Research has not identified a varient

of the existing system that is consistently related

to students’ educational

out-comes.3

- Research

tentatively suggests that improvement in student

outcomes, both cognitive and noncognitive,

may require

sweeping changes in

the organization, structure, and conduct of educational

experiences.4

-

Secondary curricula do not have to be composed

of an assemblage of subject of discipline-oriented

units

of instruction

taught

by persons whose knowledge

is limited to one major and one minor subject in

which he or she was schooled. Small high school

programs can ill afford

this approach,

either

financially

(staff size and diversity) or educationally.

-

A thematic, problem-solving, experiential approach,

coupled with an understanding of the processes

for analyzing the

knowledge, wisdom,

values,

and skills

reflected in the community and the educational

environment immediately at hand, should provide

the base for

overall instructional design.

- To understand

the world and the universe, a person must

begin by gaming knowledge of the

system

of things

immediately

accessible

and

central

to his or her life at any stage, at any place.

-

The community and its people, the creatures and the land, the weather,

the language, and

all things

which

together compose the

environment

are immediately accessible to all persons;

this environment, and its relationships

to others

and that of the whole, provides an educational

resource which

transcends that of the formal school; the

school is but one part of this educational

environment,

but from it and within it, can come the help

often needed by children and youth to understand,

and

gain benefit

from, the

broader environment.

- The perspective described

above is either not shared by many educators or, assuming

that it is,

the approach

to education

that it implies

is not generally being carried out because

it demands of the educator a

deep knowledge

of the

environment in which the school is set.

Without this knowledge the environment cannot be

explored with

young people, cannot

be related

to the larger

environment, and cannot form a secure base

from which the educator can influence the

shape of the educational system or argue

substantively for its

improvement.

- Colleges and universities

tend to prepare educators and educational administrators

for schools and

school systems oriented to the

needs of a society just past.

The shift from a reactive role to an

active and more forward looking, predictive role

is crucial

to the

reform and improvement

of (teacher)

education.

- Colleges and universities

tend to not prepare teachers and administrators

for

schools to

meet the needs of

societies, cultures,

and economic

levels different from the norms of

the larger society.

The

thirteen premises are written to espouse a particular perspective

on education. They collectively imply the nature

of a small

school’s secondary program

and system that may be appropriate for rural Alaska, and

probably other rural places as well. Conceptually, they

also apply to elementary level systems but,

since elementary schools, their staffs, and their curricula

are already established, the matter becomes one of intervention

and change, rather than new planning.

Of essence is the

implication that there are few teachers and school administrators

who have been prepared to work

with the

creation

and operation of an educational

system such as would emerge if the premises were accepted

and dealt with in systematic and programmatic terms. It’s

not a matter of wanting to or not wanting to, or a matter

of willingness to improve the schools by risking

demands for change. It’s a matter of knowing how

to go about it. For the future, it’s a matter of

the colleges and universities creating a teacher education

program which focuses on contemporary needs of society

and even projects itself a few years into the future.

Nevertheless,

the resources of the profession are available. To capitalize

on them needs only the commitment and cooperation

of

a few, the educational

leadership, who must be open to change, sensitive to needs

and cooperative in nature-with colleagues and with the

communities. The university/school/community

triad is essential.

The Process and Design

A videotape produced to illustrate a university course

titled “Rural

Community as an Educational Resource” shows under-graduate

students working with elementary children in a rural

Alaska community. Of significance

is that no classroom was needed, either by the university

professor, the teacher trainees, or the children. The

school classroom was, in fact, a base of operation,

but it could have been a community center, a home, or

anywhere that 1 5-20 children could convene and in which

a blackboard or easel could be set up.

It could have been a smaller room since desks and free ‘turf’ were

not needed for the discussion of theory which preceeded

stepping out of the building and into the larger environment.

But the school was there and was

used as it should be-not exclusively. Math theory on

measurement, time, and velocity was placed in a practical

and identifiable context by use of a watch,

measuring tape, snowmachine, and a snowy road. The finding

of field mouse burrows beneath snow covered grasses,

the removal of part of the mouse’s winter

food supply and its preparation for human consumption

dealt with a whole spectrum of man’s relationship

to the environment: conservation, survival, resourcefulness,

food preparation, and history of a people. The university,

school, community relationship was always present5.

This

is but a small example, used to illustrate some of the

multitude of possibilities by which an environmental

curriculum can be

developed in

places where the formal

facilities of the typical modern urban school and its

laboratories

are not feasible.

This is not intended to diminish the

value of modern facilities. It suggests, however, that

proper sequencing of educational

experiences throughout

a rural area is a logical approach to secondary education.

Let

us look at the five existing types of educational environments

which might lend themselves to a rounded

secondary education

experience:

- The rural community and its environs.

- The boarding high schools.

- The urban high school systems (including

Career Centers) as associated with the boarding home program.

- The existing

small area or community high schools.

- The larger rural community secondary

day schools (or day school/boarding school) operations.

The first,

the rural community, is not traditionally used as a formal educational

environment.

The second and third are those which can be capitalized

upon in an effective manner as a specific part of the

sequencing plan but

should

not be considered

as being the whole of the secondary experience.

As pertains

to rural students, the last two are those which come closest to providing

a formal secondary education without the potentially

harmful, or at least interfering, effect on young

persons (and their

families) resulting

from

removing them from

their home environment. Such schools are few in number

and their scarcity is one of the problems which gives

rise to

this examination.

Testimony from rural Native students,6

both informally and at formal hearings on the urban boarding home

program, indicates

conclusively

that a large

majority of ninth and tenth grade age youngsters

are too young to handle their departure

from home and their exposure to the city, its schools,

and the

alien cultural and social systems into which they

are thrust. The negative

manifestations

of this uprooting and new exposure will not be

dealt with here; the history of harm lies in many writings

and testimony

and

the potential

for harm

appears self-evident. However, student testimony

does indicate a positive value to

many of them, born of the resources which the urban

schools and urban society provide, as long as the

students are

mature enough

to handle

the separation-high

school juniors and seniors.7

Each of

the five educational environments has its problems

and its advantages. It’s possible to solve

or diminish the problems of each by utilizing the

advantages of the others.

At the simplest level,

the fundamental problems and advantages can be

shown as follows:

| |

MAJOR PROBLEMS |

MAJOR ADVANTAGES |

| 1. Community Environment |

Not generally accepted as a formal educational resource and thus, not

traditionally capitalized on by teachers: difficult for educators to

deal with if not familiar with the culture of the community; school!

community linkages rarely established; relevance of this environment

to the formal in-school process either unseen, ignored, or not capitalized

upon. |

A broad and deep educational resource; the place for application of

theory and academic knowledge; can make the purpose of education real

to she learner; provides for public involvement in educational processes;

a microcosm of the broader society and structure; an identifiable core

from which broader knowledge and understanding can grow; environment

for affective growth. |

| 2. Boarding High Schools |

Removes children from home at a too early age; and of parental, cultural,

and community influence; shifts responsibility for whole growth of child

to educators alien to the cultures of the students; rigid control necessary

to reduce overall group behavioral problems; isolation from community

which houses the institution; segregated-little exposure to youth of

dominant society; teachers ill-prepared to deal with education of culturally

different youth. |

Exposes youngsters to peers from other cultures and regions;

provides health care; more variety in curriculum and in-school resources. |

| 3. Boarding Home Program for Urban High Schools |

Same as previous one except shifts responsibility to a shared situation

between urban teachers and foster parents; exposure to dominant society

at too early an age without needed preparation and, too often, without

guidance; initiates racist feelings on part of urban whites when Native

students are “academically behind, slow, shy, nonverbal, homesick.” |

Same as previous one; provides an intercultural environment; exposure to urban

systems and institutions. (All of these which may benefit the more mature or

older young person will likely have a negative or harmful effect on the less

mature, rural youth.) |

4. Community or Small Area High School |

Lack of curricular variety, alternatives or depth; expensive to build,

staff, and operate in numbers needed; few teachers trained in interdisciplinary

approach; too rarely capitalize on environment of community; not equipped

to provide indepth concentration in an academic emphasis (college preparatory),

limited labs and shops. |

In or near home community of students; potential for capitalizing

on community as an educational resource; teachers and school accessible

to parents and school board land vice versa.) |

| 5. Larger Rural Community Secondary Day Schools |

Often include facilities for boarding school operation

(dorms, counselors) and have advantages and disadvantages in common with

boarding schools. Since the day schools, or day school sections, serve

only the residents of the community in which they are situated, their

utilization as part of the sequencing proposition as relates to students

from smaller villages cannot be a consideration. |

A cursory synthesis of the disadvantages of each indicates several predominant

problems: (1) the community is too seldom utilized as an educational environment;

(2) young people are removed from home at a too early age; (3) segregation

and isolation is a problem but uncontrolled exposure to the dominant society

and its structures is also a problem, not a solution; and (4) small schools

may not adequately prepare students for continuing (post-secondary) education.

Implicit overall is that educators continue to work within each of the educational

environments (except the community), and are limited by the nature of each

system. The discrete systems are not, and have never been, transcended and

so the disadvantages are never disposed of.

Yet each system has its distinct

advantages. The overriding problem is that of timing. To illustrate: for

the high school junior who has gained a certain level of maturity, security,

and

academic development, the urban high school and urban society could well

provide an academic and social experience of great value; the same high

school and

urban exposure for the freshman and sophomore is likely to be disorienting

and traumatic with disadvantages far outweighing the benefits. Conversely,

for the college-bound junior or senior student, the small high school program

which is adequate for the more average and younger ninth and tenth grade

student is likely a lacking and frustrating experience. But even if it

is not, the

first year at college will surely show the student the lack of preparation

provided by the secondary school, both academically and in his ability

to cope with the urban and university social setting.

Ignoring curriculum

for the moment, consider the positive aspects of each educational environment

in the context of timing or sequence over a four-year

secondary

experience. Broadly it would look like this:

| Yr. |

Aver. Stud. Age |

Locale of School |

Locale of Educational Experience |

Type of Focus of Curriculum |

1 |

14-15 |

Home Community |

School, Community, Field |

Interdisciplinary, Environmental, Emphasis on Communication |

2 |

15-16 |

Home Community |

School Community, Field |

Same, but emphasis on Math/Natural Science/Social Science |

3 |

16-17 |

Regional/Boarding for Some |

Rural Growth Community |

Career/Academic & Pre-Urban |

|

|

Urban Boarding Home for Some |

Urban Center |

Academic/Lab Sciences/Urban Societal/College Preparatory |

|

|

Home Community for Some |

|

Same as level ‘2’ |

4 |

17-18 |

Same as Third Year |

Same as Third Year |

Same as Third Year. (Add students to urban who may be college-bound

after pre-urban transition in Regional environments. |

This implies the need for development of a typology of secondary

students. The one suggested below should, as any other, be considered

in its

most broad or general terms, and not necessarily descriptive of any

particular

individuals:

I. Mature, Motivated, Academically Capable, High Aspirations

For these young

people the experience and resources afforded by the larger urban schools

and moving into the larger society could probably

begin

at the third-year level, following either two years in a small

school or one-year

small school, one-year regional (student/parent option.)

II. The

Average Person in Academic Capability, Maturity, and Motivation

Within

this board category can be found two general types of persons, depending

on the social and cultural situation in which

they

have lived. The potential

of each young person must be actively and objectively

examined, and care must be given to assure that cultural bias is

not a factor in

distinguishing.

- The persons from the ‘deep’ rural

areas, the small villages; limited prior exposure

to even larger rural

communities.

A Native language

is the first language and is predominantly spoken

at home. The third year could be spent at a regional

or area boarding

school for most;

some might remain

in home community until fourth year.

- The persons

from larger rural villages; may have spent time in urban or regional

growth center; English

has

been predominant,

or only, language.

Some could go to urban center (parent/student

option) and others to regional center.

For the latter, this year could be for transition

to urban school or in career

education emphasis program.

III. Less Than Average

Academic Performance, Ambivalent About Life Goals,

Apparent Lack

of Motivation

For these young people, the reasons

for below-average performance or ambition must be determined. The problems

may be born

of historically unreconciled

cultural differences between the individuals, community,

teachers, and school. They

might best be served through continuation of environmental

education focus in the home community by teaching

staff sensitive to the

problem

and able

to convey the worth in pursuing a more indigenous

life style. The fourth year

in a regional high school may be considered, especially

in a career or vocational education program.

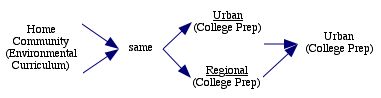

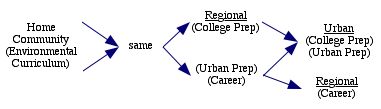

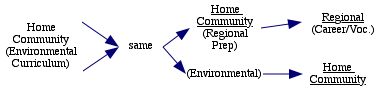

Combining general student type with educational

environment might result in a sequence such as

this:

STUDENT TYPE |

SECONDARY LEVEL

|

I |

|

II |

|

III |

|

Prevailing Throughout the curricula

at all the educational environments should

be the focus

on preparing

young

people to pursue

their lives in whatever

social or cultural milieu they may wish. The

degree of emphasis will vary and will be implicit

in the

curriculum

in each of the

different

settings.

In the

urban setting, the emphasis would be more toward

functioning in the postsecondary institutions

and, ultimately, within

the dominant

society

rather than

toward functioning in the village. Yet the

students should be able to return and

assume leadership positions in villages, regional

centers, and Native Corporations in the fields

of business management,

political

science,

law, medicine,

education, resource development, and others,

as well as to do so within the larger society.

The regional high schools would provide for

a sorting-out

process, a transitional experience, and career

or vocational emphasis to enable students to

take up

positions ranging, for example, from village

to regional to urban entrepeneurship.

The home

community secondary school as envisioned

here is probably the greatest departure from

conventional concepts of educational

systems. However, there

is nothing that substantiates

the idea that the institutions of one society

have usefullness in another. And that idea

is even more

unsupportable if the institutions are created,

peopled, and run almost exclusively

by and for the dominant society. The relative

failure of the educational institutions

in general, and public schools specifically,

to meet the needs of the rural Native Alaskans

(as

well as

other minorities

and

low-income persons

throughout

the nation) illustrates the point. Yet proposed

solutions on the horizon appear to be: an expansion

of the

institutions and

their

edifices and

traditional program and the shift of their

control to representatives of the local

populace.

The latter is a critical moral and political

necessity. However, as pertains to the cultural

minorities,

the institutions remain operated

by the dominant

society, owned by the dominant society, and

represent the ideals and perspectives of the

dominant society

which created

them in

the first

place. When, and

only

when, the institution becomes a functional

part of (not merely involves or serves) the

community,

does

it become

of real use

to that community

and its

citizens. Given this thesis, let us examine

the secondary school as an institution of the

small

community.

A potential system for sequencing

rural secondary students through a four-year

educational program

which utilizes

existing and reasonably

attainable,

resources and facilities has been outlined.

As traditionally understood, small high

schools would have to have several specific

characteristics in order to provide adequate

and equal educational

opportunity for

the rural

youth:

- An edifice containing classrooms,

a gymnasium, equipped laboratories for biology, physics,

chemistry (and electronics),

shops.

- A diverse teaching staff, each

member having been schooled in one or two specialities

in

order to cover

economics,

government, mathematics,

physics,

geology, English, foreign language,

art, music, speech and drama, physical education,

typing,

psychology, home economics, chemistry,

wood and

metal shop, environmental science,

mechanical drawing, geography, history, and

so forth.

To provide this for, and throughout,

four years at the various levels of depth necessary

in

a school whose total

student populace

is less

than 100,

is not

only unsupportable but unnecessary. The magnitude

of the problem and cost is so great as viewed

by school

authorities,

the legislature,

and the federal

government that only minimal services are

likely to be made available. The costs of

construction

and

staffing

increase yearly, so no

magic occurrence in the future will make

the financial solution easier.

Predictably,

the

matter

will be addressed in a patchwork manner while

generations of young people grow

out of school age and while postsecondary

institutions struggle with their legal roles

as pertain

to remedial programs of pre-postsecondary

nature.

By contrast, two or three year community

secondary schools, set up at the ninth and

tenth (and

for some cases, eleventh)

grade

level

equivalent, don’t

require the formal lab facilities; these

are available in the regional and urban schools,

accessible at a later time in the sequence.

The same with the

home economics room, physical education facilities,

and even formal music rooms. The variety

of disciplines or areas of study need not

be available at every

level; this is a matter of sequencing. Thus,

the variety of teachers with their specialties

doesn’t have to exist on

the small schools staffs; they are accessible

at other places at other times,

depending on

the various routes

that the different students take. Again,

a matter of sequence.

The history, knowledge,

wisdom, and language of a community and a

culture are available

from the

elders,

the parents,

the hunters,

and council

members of

the community. They have not been brought

into the educational process,

and they must be. Developing an understanding

of the society and social structures

of the community as a slice of the society

as a whole, and how they relate to the larger

society

of region,

state, nation,

and

world

can be a rich

and comprehensive educational enterprise,

augmented by touching the reality of

the learner’s environment. The ecosystems

of the lake, the tidal flats, the streams,

the tundra, the snowfields

and woods are

the richest of all possible

laboratories for the natural sciences, as

are the aurora, winds, and storms and long

cloudless

times of darkness.

It is to the villages,

forests, tundra, and gravel streams that

outside scholars, bureaucrats,

and

advanced students

come to

study anthropology,

geology, meteorology,

history, linguistics, sociology, mythology,

biology, and fisheries, forest and land

management. The

people are studied

so that they

can be taught.

The efforts are also aimed toward adding

to the broad body of knowledge and toward

exploration for purposes of ultimate exploitation.

Yet the young people who live in, and are

a

part of, these

rich environments

are placed

in institutions remote from where it all

is, both physically and intellectually,

to pursue

the education

deemed traditional

and

right for them by those

who follow the paths which their educational

predecessors laid in some past epoch.

It

is necessary, therefore, to create new

curriculum content and processes to fit

within the context

of what is proposed

herein. Granted, it will

require the preparation of a new type

of teacher and educational administrator.

This implies

the need for

new perspectives

by the

postsecondary institutions.

However, as noted, there are a sufficient

number of such educators now who see

things in this

light to enable

progress to begin.

The curriculum developers must come together

with the facilities planners.

The superintendents

must bring selected teachers and parents

and school board members together. The

universities and appropriate

research

institutes

must identify

those

few representatives who can, and will,

commit themselves to an examination of

the

issues and procedures. The parents and

interested lay citizens must be involved

and participating in the shaping of policy

and plans.

The focus of thought and planning

should not be upon the ways in which

the existing

systems

(as

school

buildings, curricula,

teaching

staffs,

administrations)

of the dominant society can best be

transplanted into small

rural community settings. The focus

should be upon questioning the

efficacy of such

ideas and upon finding the solutions

which may lie elsewhere. The community

school

is too often only seen as a place which

the

community can more fully utilize. Rather,

it must be

seen that the

community is the educational

environment

in which the school and staff provide

a convenient and important setting

for the

orderly exploration and examination

of what

the total environment provides.

FOOTNOTES 1. 4AAC 05.01 0-05090, State Board of Education.

2. Averch, Carrol, Donaldson, Diesling and Pincus, How Effective is Schooling,

A Critical Review and Synthesis of Research Findings, Report to the President’s

Commission on School Finance, Rand Corp., 1972.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Grubis, Steve, University of Alaska, X-CED Program, Spring, 1975.

6. Kleinfeld, J., A Long Way From Home, University of Alaska, CNER and ISEGR,

1973.

7. Ibid.

|