Every student has ways of making sense out of the world that

surrounds them. It is vital that teachers find new and innovative

ways to instill confidence in their students so that children can

trust their own powers of observation, utilize their own style of

learning, and feel comfortable making rational and logical

connections that expand their knowledge. Developing these skills is

important in learning effective problem solving. Statistically, rural

Alaska students have a poor track record in academic institutions.

Their education has been dominated by a culture that makes little

sense in their immediate experience. There is a serious need to

harmonize traditional ways with western culture if these kids are to

succeed.

Children raised in a rural Alaska village have an intimate

knowledge of winter and snow. What they probably have not come to

realize is how this knowledge has already given them a strong

foundation for such subjects as chemistry, math, and ecology. All of

these children have grown up with a traditional culture interacting

with a modern one, and a network of community members and Elders. Few

have made the connection between complex environmental science and

the knowledge of their grandparents. Faced with huge environmental

challenges, western science is now looking to traditional cultures

for ways of living sustainably on a finite planet. The goal of the

Denali Foundation's snow curriculum is to help make these connections

in the minds of each student. Sound environmental education starts

with a strong understanding of how the natural world functions and an

appreciation of the vast web of interdependencies that we all rely

upon.

Programs that seek to teach scientific methods of environmental

science must realize that there is a strong foundation of traditional

knowledge and a reverence for the natural world. This is a great

setting to teach children the scientific interrelationships of the

natural world. There is a serious need to help students learn not

just good scientific information, but to develop critical thinking,

problem solving, and effective decision-making skills.

The Observing Snow Curriculum of the Denali Foundation

directly targets many of these issues with a strong science program

that employs a wide variety of learning techniques. We also seek to

root the learning experience directly into the local area and to

incorporate traditional native knowledge as an integral part of our

curriculum. Parallel chapters will guide students in an exploration

of snow from scientific and indigenous points of view.

We wish you a pleasant journey as you help school children unravel

the mystery of the winter world as seen through both the eyes of

Native elders and the methods of Physical Science.

for the

Teacher

Cultural Standards:

Educators

A1

Recognize the validity and integrity of the traditional

knowledge system

|

Traditional Knowledge and the

Modern School

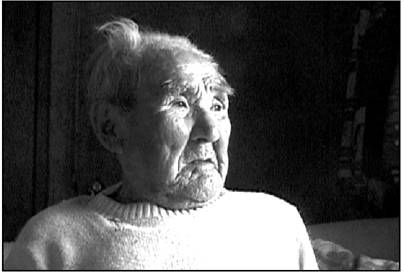

Traditional knowledge is exemplified in this curriculum

by the words of four Elders from Minto, Alaska, whose

comments were recorded in the Fall of 2000. Excerpts from

those conversations indicate the kind of snow-related topics

Elders wish to discuss and the kind of values they choose to

emphasize. Teachers and students will find similar concerns

and knowledge in their own communities, but the specifics

will vary from place to place and from one elder to another.

In addition to conducting the activities suggested in

this curriculum, students are encouraged to pursue related

topics and document what they learn. You may decide to

document the activities of other seasons or to expand the

study of geography based on the mapping exercise and place

names discovered here. Or you may use these exercises as the

start of a student conducted oral history project for your

area.

Alaska Native Elders have much to teach, a lot of

traditional knowledge to pass on, and a strong desire to

assist in the education of the children in their

communities. Working with the Elders can not only improve

the quality and relevance of classroom instruction, but can

also improve a teacher's connections with and understanding

of the communities in which they teach. However, the

establishment of formal schooling in rural Alaska has

profoundly influenced Alaska Native ways of life and

cultural practices, so Elders in your community may be

ambivalent about western schooling. The large amount of time

children spend in school has been disruptive to traditional

forms of education, and the school system has been a major

contributor to the demise of Alaska Native languages. The

Elders may have had unpleasant experiences with the local

school and may not be comfortable there. Nevertheless,

working with Native Elders to bring local knowledge into

your curriculum is highly rewarding, and you will be

surprised by the depth of knowledge they can bring to your

class and the enthusiasm which students will have for

discovering connections between scientific investigations

and Native ways of knowing.

The readings presented in Observing Snow are a small

sample of what the Minto Elders have to say about snow. They

have generously agreed to share their words to help kids

begin to explore snow related knowledge in their own

communities. The readings can be done individually or in

class. The Class Discussions are intended to provide

practice in making inferences from oral teachings and should

be used to both discover what students already know about

snow and to highlight concepts which might be useful in

integrating indigenous and scientific perspectives on snow.

|

|

|

" Old Minto is Menhti

Xwghotthit. That's where I grew up. That's where I was

born, down in Old Village. We used to move around. I think

1930 school start down there, and since that time people

start to stay in one place. They quit moving around, 'cause

kids have to go to school. That's after we grow up, after I

get married. I didn't have that kind of opportunity to go to

school. There was no school until 1930. I was happy for

school because I didn't go to school, and I'm for education.

I like the kids to go to school. It's good for them.

- Evelyn Alexander"

|

|

Working with

Elders

Start early. Several weeks prior to starting the

curriculum, ask your students and their parents about who in

the community might be willing to share traditional

knowledge on the topic you are interested in. Talk to the

bilingual program teacher at your school. They probably know

the community well. If the bilingual program teacher is

available and willing to participate in the snow science

curriculum, you'll be much better able to accurately

transcribe the Native language terminology encountered, and

perhaps material from this curriculum can be incorporated

into language instruction.

Identify local experts. Ask community members. A

recommend form for this is: "Who around here knows about

snow and winter survival?" Typically you'll be directed to

Elders, but encourage other community members to

participate. Ask the Elders. They are very aware of who the

experts are on any given topic. You'll probably want to find

3-4 Elders to participate, depending on the size of your

class. A ratio of 3-4 students per Elder is good; 5-6 might

be OK.

Ask politely. Don't be afraid to ask the Elders

for help, but be careful not to pressure them or put them in

a position where it would be uncomfortable to say no. If an

Elder can't help you with this topic, maybe they can help on

a future topic. Don't expect an immediate answer; it may

take folks a little time to decide amongst themselves who is

best able to help with this particular project.

Be clear about the kind of project and amount of

participation you require. The Observing Snow curriculum

consists of a day-long field trip, 2-3 hours of discussion

with students about traditional lifestyles, 1-2 hours of

talking about native snow terms, and an optional 2-3 hours

of participation in the snow shelter and snow pit exercises.

Be patient. Discuss the topic in advance with each

Elder or local expert. Ask general questions and not too

many of them. Listen. Give them time to warm to the topic,

and you'll be impressed with the stories they tell. Assume

that what they tell you is relevant, even if you don't get

it at first.

Find a comfortable context for sharing traditional

knowledge. The workshop begins with a field trip to teach

traditional outdoor skills. This will be the most

comfortable setting for the Elders. It might work best to

find a neutral setting such as the local community center

for the kids and Elders to discuss traditional lifestyles

and snow terminology. You'll probably choose an outdoor

location near your school to conduct the snow shelter and

snow pit exercises, so invite the Elders to observe. After

working with you for a while, the Elders may be comfortable

enough to work effectively in your classroom.

Express thanks to the Elders at the end of the

curriculum. Perhaps the students can report back to the

Elders on what they learned and thank them personally.

|

Cultural Standard:

Curriculum

C4

Views all community members as potential teachers

|

Reading

|

Neal and Geraldine Charlie Talk

About Education

Neal and Geraldine Charlie, along with Evelyn Alexander,

participated in our Snow Science Workshop in the spring of

1999. The following discussion highlights Neal and

Geraldine's feelings about the current educational system

and how native communities and Elders can contribute to the

education of their children and grandchildren. As you read

their words, notice what they have to say about traditional

values, traditional modes of instruction, and how schools

can facilitate the incorporation of traditional knowledge in

the curriculum.

The following discussion was recorded on October 26, 2000

at the Charlies' home in Minto, Alaska. It is edited lightly

for readability while maintaining the feel of an oral

narrative from folks whose use of their second language is

quite expressive. Notice that a transcription of spoken

language is a little different than formal written language.

This is true for people everywhere. Most of that day's

conversation is included, with gaps indicated by ellipses

(...) and editorial clarifications or comments in

[brackets].

How did you decide what to teach

the Minto kids in the Spring of 1999?

Neal:

I tell you, we lose too much of our native way. We already

lost too much. And it's one of the things we decided, that

we should start teaching our grandchildren things. Right

now, our age. We used to go out there someplace with our dad

or our older brothers, and they teach us what we have to do,

being out there. That's the Indian way, find out things.

Right now we hardly see our kids. Leave eight o'clock in the

morning. Neal:

I tell you, we lose too much of our native way. We already

lost too much. And it's one of the things we decided, that

we should start teaching our grandchildren things. Right

now, our age. We used to go out there someplace with our dad

or our older brothers, and they teach us what we have to do,

being out there. That's the Indian way, find out things.

Right now we hardly see our kids. Leave eight o'clock in the

morning.

Geraldine: They're in school all day, not learning

nothing at home. Most of them don't know nothing about going

out, how to build fire, how to survive.

Neal: And that's the kind of things we're facing

today. That's not only here, it's like that in Fairbanks,

everywhere. I think that there's really a lot of important

things young people learn out in the country, out on the

land. Cause animals themselves are created by God and they

got lots that they can teach, animal. And we were taught to

respect animal, don't laugh at animal. How can you laugh at

something your gonna eat? We see them crazy things, they

make hamburger dance before they eat it, on TV.

Geraldine: He means them commercial [a

television commercial for a fast food restaurant]. Yeah

there's commercial about hamburger jumping around and

talking. And our old Traditional Chief Peter John, he got

mad when he saw that. It's not right, he said.

Neal: We were taught to respect animal. If you

kill him, if you kill him to eat, you make sure you use all

of it. Make sure you use it all. Like if they kill moose, we

use the stomach, we eat the marrow. Just the bones we don't

eat on moose. We use the head, the meat on the head. We use

the moose skin for clothes. So that's the kind of things

that our children should know. So they don't play with

animal or laugh at animal, stuff like that.

Geraldine: We were taught to respect each other,

too. Never put each other down. And we were always taught to

help. If you know your neighbor or friend need help, you

gotta help, don't let it go. It was all these things they

taught us. Never talk back to Elder. If an Elder tell you

something, don't talk back; that Elder know what he's

talking about. Like right now today teenagers get mad at us

if we tell them what's right. They don't know any better. I

find out a lot of kids, right now their mothers and fathers

don't teach them like we used to, long time ago. It's really

hard to get along with that.

|

Neal: Another important thing that they used to tell young

people is, don't laugh at crippled people. Don't laugh at blind

people, or people that can't hear. Or if you see a man walking,

paralyzed one side, don't laugh at them kind of people. They used to

tell young people that kind of thing. Don't pass up old man or old

lady. If you see they need help, you help them right away on what

they're doing. What happen is, maybe that old person might pray for

you so that you'll be in good health or you'll be lucky. That's the

way they advised our young people. They don't only talk about snow,

they talk about life [laughs]. What really life is. And be

careful. Be careful with axe, be careful with knife, be careful with

your gun. Right now kids and people just use guns to hurt each other

and I think that's just plumb wrong, there. Axe and knife and gun is

very good tool when you're out in the woods, and that's what it's

for. I'm just talking about the advice they used to give us. And

today, after we get pretty old, we find out that's right. What they

used to say is true.

.....

Another thing they used to tell our young people about is don't talk

too fast. Don't say things you'll regret. Don't brag in front of your

friends. Right now today we hear kids say "I'll kill you." That's an

awful dirty word there. That's not right to say that. That's plumb

wrong to say that kind of thing, especially when they're just

starting out in life. They should never use that kind of a talk. I

think this world would be a lot better off if we get back to loving

one another. And try to do good to each other. In our language we

call that hwtlani [taboo]. Hwtlani means if you

say "I'll kill you," it might happen that way.

Geraldine: Your words might come true.

Neal: What you say might happen. If you think bad about

your friend it might happen; that kind of thing. So you try to keep

your mind clear all the time. Try to think about the good thing, that

kind of thing. That's what you call healthy for young people.

Geraldine: There's a lotta lotta more things. You can sit

there all day, all week and you'll pick up a lot of things we use in

our life.

Neal: There's a lot of ways we could talk about in front of

young people. Young people is not seem to be listening the way they

should be listening. The young people are not listening hard enough.

How did your Elders teach?

Neal: The way we're talking.

Geraldine: I remember my grandmother used to tell me,

you're going to that certain person, so just sit down. She'll tell

you a lot of things you need to know. And I used to do that. That's

how I learned to sew, a lot of things. She told us a lot of things,

that old lady. Stories, about how to make a living. Our parents think

we're too tired of listening to them so they send us to somebody

else. (laughs) He'll [the boys] have to go to somebody else's

house and listen to another person tell stories. That's how we

learned.

Neal: We used to gather up in one old man's house. And he

used to tell us stories. He tell us about stuff like that. That's

what you call Indian education. We're talking about stuff here that

young people should know.

.....

It used to be very, very important that we understood our native

languages. They had to teach us that, 'cause they can get across

better to us in our native language. And I think that's one of the

really truthful things we're missing, as Native people. I believe

that we need to get back to our native languages and understand one

another.

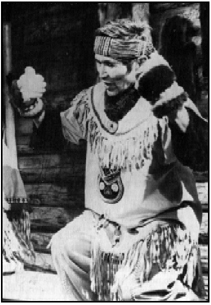

River Times, Fairbanks, Alaska

Neal Charlie, son of Moses and Bessie Charlie, in modern dance

dress.

Photographed possibly at the Eskimo-Indian Olympics,

1970

Did they tell you a lot of traditional

stories?

Geraldine: Yeah, we pick up the good parts of it. Sometimes

when they think we get too bored they tell us funny stories in

between, you know. Make us laugh. It gets pretty interesting when

they do that, you know. Otherwise we just sit there and listen,

listen, listen. But some people will find a little time to tell us

jokes and funny stories. After that we start all over again. Just

like going to school.

Neal: And them old time stories was really interesting

because we understood them. And right now if I tell a story about the

one that died here a long time ago, speaking this language I don't

tell it right. I don't tell it the way it should be. Last night

[at a memorial] them old people they sang some of our old

native songs.

Geraldine: Mourning songs they call it.

Neal: Them songs could get back way back before we seen it,

before our time. It's like they speak to us again. They tell us what

it was like way back then. And today we find out it's just the same

thing. When they sing them it sounds like it's still the same. That's

the way they used to teach us. Stories and songs and advice. They

explain who made the song, who it's after, and the meaning of the

things in the song. That's part of the way we had to learn. There was

no paper and pencil them days.

Where and when did your Elders tell

stories?

Geraldine: In the evenings is when everybody quit working.

Every evening is when we used to go around for story time. Take a

walk to somebody's house. In the daytime everybody's too busy. Until

school start is when everybody just changed the whole thing for us.

They had to go to school and spoil everything for us. Maybe that's

where I learned how to speak English [laughs]. Yeah, I'm

pretty sure if there was no school we would just speak our language.

Neal: Anyway, I think that there's a lot of it that they

had to repeat it over, over, over. They have to repeat it. It's not

just one day thing. They pound it right into us, because nothing is

written down, you have to remember.

...

And that advice, you better listen, cause it's not gonna be written

down. Your gonna have to accept it and try to hold it. Just like old

man Chief Andrew Isaac said. One time I hear him say, lots of advice

old people used to give me. He said lots of it I get a hold of it, I

hold it, remember it, he said. And I think that's one Indian way,

that's Indian way. That's the way they have to learn it. Not to look

at it on a paper all the time. They gotta use their little brains for

something [laughs]. My dad before he died, I don't know how

many times he made that same speech. You young people try to hold

each other together. Try to hold each other together. Try to hold

each other together. He repeated that quite a few times. All good

solid advice. Today right now it's all true, it's all true. It's good

to take care of yourself. That's a short cut way to say it. Take good

care of yourself.

How do you feel about Elders teaching at

school?

Geraldine: I believe that, like he said, if we had our own

place we'd be more open, more free to talk the way we want to talk.

But up there [the school] we gotta watch the time. Hurry up,

hurry up, hurry up. Twenty minutes or ten minutes is all the time

they give us.. They do make time, but you can't teach nobody in 20

minutes.

Neal: Like we said before the way they learn is they had to

sing these songs in between. And then after that they get to advise

the kids about things. And we can't do that up there, we can't do

that in that school building. Another thing is that we're pressed for

time for telling stories. If we're gonna tell a story it might take

quite a while to do that, that kind of thing. If we have our own

place where we feel like we could just do it, we might have a better

chance at it. You really want to get down to brass tack of things,

the only way you really could do it is put a camp out there and stay

in that camp for a while. To show the young people how if they need

to build a sled or snowshoes you have to look for certain kind of

birch. And teach them that kind of thing. And teach them how to hunt

bear den, teach them how to set snare for rabbits, Indian way. We use

sinew. They catch rabbits and ptarmigan in them, them snares I'm

talking about. The only thing is, rabbits you gotta set different

from the way you set for ptarmigan. You make it so it'll spring up

and that rabbit will hang down, so he doesn't chew that sinew off.

That's what I've been saying. You really want to get down to it you

gotta take it out there, where it's at, out in the country. Get them

out there where the action is, then they'll learn.

Discussion:

- How were Neal and Geraldine taught by their Elders?

- What are the important things they feel young people should

learn?

- What values do they emphasize? Can you think of other

traditional values in your community?

Activity: Field Skills with

Elders

Ask

Elders and Local Experts to teach you traditional

winter skills in the field.

Time: 6-8 hours

Materials: Tools and Equipment appropriate to the

activities

recommended by your Elders and Local Experts

This activity is a good way to introduce the snow science

curriculum by giving Elders a chance to teach what they know

best in an environment in which they are comfortable. Topics

related to the winter environment are chosen by the Elders

depending upon their particular areas of expertise. Examples

include, emergency skills such as fire making, shelter, and

making meltwater. General technical skills might include

snowshoe technique, tying snowshoe bindings, trail breaking,

and tracking.

Making tea from snow water is fun and involves

relevant skills and observations.

Arrange for a field trip. Small groups of student with

each Elder is preferable.

Have students document what they learn and check their

conclusions with their Elder instructors. Later they'll make

connections between the practical skills and observations

from the field trip and the scientific concepts they learn

about snow.

|

Cultural Standard:

Schools

B2

encourage experimentally oriented approaches

|

|

Cultural Standard:

Educators

provide opportunities for students to learn through

observation

|

Discussion

- What skills do Elders choose to teach? Why do you think they

chose those topics?

- Are traditional skills important to us today?

- What do local experts know about snow? How do snow conditions

affect traditional activities?

Traditional Education is based on observation, practice, and the

oral transmission of knowledge. Despite the relatively rapid pace of

cultural change that has taken place in Alaska during the past

century, a great deal of traditional knowledge is being practiced in

Native communities today, and Native Elders, having spent a lifetime

learning their culture, are ready and able to pass it on. Schools can

contribute to the success of their students and well-being of their

communities by incorporating native knowledge in their curricula.

|

" To make your luck better

you gotta take care of yourself. Neat, nice and clean.

Xo'iltanh, they say.

Xo'iltanh means try to stay nice and clean,

don't do anything wrong. If you do something wrong, bad luck

will turn against you. Xo'iltanh. My dad

give me a lot of advice every morning before he go out,

before he go hunting. Just like going to school. He talk all

Indian, too, he don't talk no English. When you're going out

in the woods or anyplace like that, any place where you're

gonna travel. We say k'onaniltayh.

K'onaniltayhmeans be careful yourself, be

careful of danger.

- Wilson Titus"

|

Observing Snow

Introduction

The Four Corners of Life

Water: the Stuff that Makes Snowflakes

Snow on the Ground Changes Through Time

Exploring Native Snow Terms

Glacier Investigations

Open Note Review

Conclusion

Bibliography & Resources