|

Sharing Our

Pathways

A newsletter of the Alaska Rural Systemic

Initiative

Alaska Federation of Natives / University

of Alaska / National Science Foundation

Volume 6, Issue 5, November/December 2001

In This Issue:

Documenting Indigenous Knowledge

and Languages: Research Planning & Protocol

by Beth Leonard

Introduction

I have been preparing a research proposal for the

Interdisciplinary Ph.D. program at UAF that focuses on "Athabascan

Oral Traditions: Deg Hit'an1 Narratives and Native Ways of Knowing." Much

of my current research and language learning centers on kinship

and (personal) family histories. Hopefully this research will serve

dual purposes in terms of both academic significance and potential

value to the Deg Hit'an community.

Research by indigenous researchers for the benefit

of indigenous communities also dovetails with political/postmodern

movements of self-determination, autonomy and cultural regenesis.

Maori researcher, Linda Smith (1999) states: "The cultural and

linguistic revitalization movements have tapped into a set of cultural

resources that have recentred the roles of indigenous women, of

Elders, and of groups who had been marginalized through various

colonial practices" (p. 111). Although some Deg Hit'an Elders were

recorded during the Alaska Native Literature Project and more recently

during the development of Deg Xinag Dindlidik: Deg Xinag Literacy

Manual there remain several Elders who have not had a chance to

record traditional stories and/or lend their perspectives to the

history of this area. Deg Hit'an narratives will be valuable as

language maintenance efforts proceed and more emphasis is placed

on integrating Native knowledge and history into the school curriculum

through projects such as the Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative.

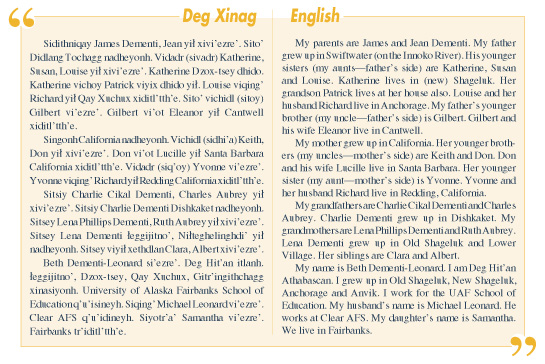

Researcher's Background

I grew up in Shageluk, Alaska, an Athabascan village

on the Innoko River located in the lower-middle Yukon area. I also

spent four years in neighboring Anvik, a village on the Yukon approximately

30 miles from Shageluk. My father is James Dementi of Shageluk,

a multilingual speaker of Deg Xinag and Holikachuk Athabascan and

English. My mother, Jean Dementi, who died in 1988, was a non-Native

woman who came to Alaska from California as an Episcopal nurse-evangelist.

In 1976 she became Alaska's first woman ordained to the priesthood

in the Episcopal church.

Due to a variety of socio-historical influences,

most people of my generation did not learn to speak Athabascan.

Both the early Episcopal church missionaries and the territorial

and Bureau of Indian Affairs schools mandated English and parents

had been told not to teach their children the Athabascan language.

During the time I lived in Shageluk and Anvik, there were no Athabascan

language programs in place in either the school or community. I

do, however, remember the first linguists from the Alaska Native

Language Center (ANLC) who came to the Shageluk area to work with

speakers during the early 1970s. My father and other relatives

often worked as consultants in these early language documentation

and translation efforts. This contradiction in Native language

status, i.e. continuing suppression of local language and culture

by churches and schools versus promotion by prestigious outside

academic interests, conveyed ambiguous and confusing messages to

communities struggling to maintain their local cultures.

Barriers and Challenges in Language

Learning

In my current role as language learner-along with

other language learners from the Deg Hit'an area-I find myself

struggling with the best way to learn the Deg Xinag language and

share the knowledge I have documented. Although many of us as language

learners work directly with linguists, obvious differences between

English and Deg Xinag Athabascan are not articulated and we (the

learners) are forced to stumble along as best we can. I believe

this is due in part to the lack of knowledge of the deeper Athabascan

cultural contexts and constructs and the failure to document language

beyond the lexical and grammatical levels.

I was an undergraduate linguistics student when I

began my study of Deg Xinag. At that time I had no experience in

learning a non-European language and was accustomed to being taught

conversational language by experienced teachers using immersion

methods. I was also used to having an extensive collection of practical

dictionaries and grammars at my disposal to assist in the learning

process. Although there is not a published grammar for Deg Xinag,

there are materials that can be used for language learning. To

date, publications include one set of verb lessons, a language

curriculum for elementary students, one literacy manual, two books

of traditional stories, several short children's stories and a

limited collection of supplemental learning materials. The verb

lessons explain the linguistic structures at an elementary level

for language learners, however, as stated above, significant cultural

constructs and concepts are not addressed.

Through my academic coursework I would often run

across barriers to my own self-confidence in being able to someday

speak Deg Xinag fluently. For instance, there is a whole body of

research on second language acquisition that says if learning begins

after adolescence, the learner cannot expect to become fully fluent

in the second language. In a similar vein, linguists often describe

Athabascan "as one of the most difficult languages in the world

to learn," thereby insinuating that one needs to be of above-average

intelligence to indeed even attempt such a process. As a learner

and student I have been questioned as to the potential for true

authenticity (purity) of Athabascan when learned as a second language

and whether or not I think the "back velars"2 will drop out of

the language.

I began my own language learning by asking for phrases

in the languages and listening to taped narratives and literacy

exercises. I also would sit down with my father and go through

sections of the noun dictionary to find the literal meanings of

words. I found that, although writing and studying written language

is not considered the best way to learn conversational language,

it provided a base for further understanding of the language structure

and helped with learning the sound system. I continue my study

of conversational language through regular interactions with various

members of my immediate and extended family. Sometimes this learning

takes place in more formal environments such as the ANL 121/122

audioconferences or Athabaskan Language Development Institute's

on-campus classes. On most occasions this learning takes place

through informal interaction with speakers through visits or phone

conversations. I still use a variety of learning methodologies,

including writing the language on a regular basis.

One of the more popular ways to teach/learn language

involves a method called Total Physical Response (TPR). In English

this would require the use of the imperative mode to give a series

of commands which require some action on the part of the learner,

e.g. come here, open the window, close the door, etc. In Deg Xinag,

however, many of these do not equate to commands but describe instead

what the subject is doing. In the case of "wake up" for instance

(when speaking to a child), a more appropriate way to express this

in Deg Xinag is "Xejedz tr'aningidhit he'?" which translates

to "Are you waking up good?" Examples such as these reflect the

deeper value system, i.e., a gentle way of relating to children

as they awake.

I am continually impressed with the Deg Xinag speakers'

command of English and Athabascan and their strength and resilience

considering the damage that has been done since contact. In the

past there was a great deal of travel and intermarriage between

the Deg Hit'an and Holikachuk areas, so many speakers have command

of at least two Athabascan languages. As multilingual speakers,

they are aware of our difficulties in learning these languages

and are able to provide the context we often ignore. I have observed

that in immersion or partial immersion situations, speakers will

adapt their use of language so as to not totally overwhelm, but

assist learners through individual levels of learning by varying

the complexity of their speech.

Language Learner As Researcher

"Alaska Native worldviews are oriented toward the

synthesis of information gathered from interaction with the natural

and spiritual worlds so as to accommodate and live in harmony with

natural principles and exhibit the values of sharing, cooperation,

and respect" (Kawagley, 11).

Kawagley's observations about Alaska Native worldviews

are reflected in my initial research with the Ingalik Noun Dictionary.

In reviewing this dictionary with my father, I found that the literal

translations were not included. For a beginning language learner,

literal translations provide a great deal of fascinating cultural

information and further impetus for investigation into one's own

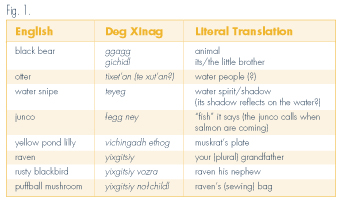

culture. For example, the Deg Xinag words for birds, fish, animals

and plants reflect complex and scientific beliefs and observations

(Fig. 1.)

Culturally Appropriate and Respectful

Ways of Language Learning

Learners, like myself, who do not have latent knowledge

of the language, use a translation approach. Often we inadvertently

ask for words or phrases for concepts that do not exist, or concepts

that are expressed in very different ways in this cultural context.

Learners also tend to provide an incomplete or sometimes total

lack of context when requesting words or phrases. As English speakers,

we nominalize and decontextualize many concepts, without realizing

that Athabascan is a dynamic, verb-based language.

One example of differences between Deg Xinag and

English categorization reflects the way one would say "Where are

you/where is it?" Xidanh is used when referring to people (e.g.

Xidanh si'ot?-Where is my wife?), whereas xiday is used to refer

to an animal or object (Xiday sileg?-Where is my dog? or Xiday

sigizr?-Where are my mittens?) The same is true for counting people,

animals or objects (nijtayh/nijtay). From what Deg Xinag

speakers have said, using these words for "where" and "how many" show

respect toward animals who might be offended if the wrong reference

is used. This reflects a context of care and respect for animal

spirits and other non-human spirits present in the environment,

as well as the power of the spoken word.

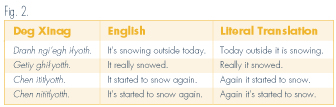

When learners request generic phrases for weather,

for instance, it can be difficult for speakers to provide this

information when not given a particular context. A more holistic

context might provide the following information:

• whether a phenomena is happening now, a

little while ago, yesterday, last week, etc.

• if a phenomena is/was happening for the

first time during the specified time period, or is/was beginning

again

• variations in intensity-a little, very

hot/really windy, etc.

These limited examples gathered by members of the

language class reflect both major and subtle changes in context

(Fig. 2.)

Documenting Oral Sources and Research

Issues

I write down new words and phrases gathered from

speakers in my family during phone or face-to-face conversations

and audioconference classes. I also record speakers (with their

permission) when possible and have several tapes of recorded audioconference

classes as well as phrase lists. In the past, I had not really

thought about the proper way to obtain permission to record information

either in writing or with audiovisual equipment. Often I would

ask if I could record, but assumed the speakers knew I would use

this information for learning purposes. Now I realize that there

are a great many issues to deal with when documenting in writing

or with audio/visual equipment, including:

• Who should have ownership of audio/visual

materials?

• How will the material be used?

• How will the material be cared for?

• Where should materials be stored?

• Who should have access to the materials?

"Just Speak Your Language"

Lately, it seems the endangered languages bandwagon

is a popular vehicle for access to "other," providing many opportunities

for publication through description and analysis of various Native

language revitalization programs. Outside researchers continue

to debate the authenticity and effectiveness of projects and programs

from non-indigenous perspectives. Language revitalization, instead

of being viewed holistically within social and cultural contexts,

is often treated as strictly a linguistic venture, i.e. "just speak

your language." "Just speaking your language" assumes abilities

and resources are available to assist in this process. It involves

learning cultural constructs and concepts often hidden in translation

along with a myriad of other environmental, ideological and personal

factors. Fortunately there are now indigenous educational models

providing examples of contextual/situational learning that can

be applied at a local grass-roots level.

References Cited

Kawagley, A. O. (1995). A Yupiaq Worldview: A Pathway

to Ecology and Spirit. Prospect Heights, Illinois: Waveland Press,

Inc.

Smith, L. T. (1999). Decolonizing Methodologies:

Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed Books Ltd

|

Guidelines for

Strengthening Indigenous Languages

This booklet offers suggestions for Elders,

parents, children and educators to use in strengthing their

heritage language with support from the Native community,

schools, linguists and education agencies. 28 pages, free.

For more information on obtaining coies of

these and other cultural guidelines, call the Alaska Native

Knowledge Network at 907-474-1902 or email dixie.dayo@uaf.edu. |

Guidelines Adopted for Alaska Public

Libraries

by David Ongley

The state of indigenous librarianship is stirring

across regions in Alaska. There is yet a long way to go. Many villages

have no public libraries. For those that do, there is no centralized

planning effort. Village libraries frequently consist of a few

shelves of books in a village council office. Funding for staff

and collections is usually far from adequate. Funds for operations

are almost nonexistent. Staff rarely work full time and usually

have few benefits. Most have little or no training in librarianship

and work in relative isolation.

We are fortunate on the North Slope to have public

libraries in all of our villages. We only have seven villages outside

of Barrow though. AVCP in Bethel is working to form libraries in

many of the 50 or so villages it serves. I hear of good things

coming from Southeast Alaska as well. Sealaska and the Central

Council of Tlingit & Haida Indian Tribes both recently received

grants for library projects, as did Igiugig Village in the Cook

Inlet area. Haines public library is working on a large project

with the Chilkoot Indian Association. For the most part, however,

very little is being done in larger towns and cities.

Each year, the Alaska State Library hosts a three-day

leadership institute that is fondly referred to as DirLead. Last

October the directors of the 10 largest public libraries in the

state met to learn ways they could better serve Alaska Natives

in their libraries. As this was a significant departure from previous

DirLead institutes, much credit needs to go to Karen Crane, the

director of the State Library and several other key people, who

immediately perceived the value of what was being proposed and

provided firm support for the project.

Father Michael Oleksa spoke for half a day about

communication styles. For the next day and a half, Dr. Lotsee Patterson,

a Comanche professor of library science at the University of Oklahoma,

a preeminent expert on Native libraries across the country, worked

with us to develop a set of guidelines for public libraries. These

guidelines were based on those for schools, communities, teachers

and parents already developed by the Alaska Native Knowledge Network.

Immersion in the subject under Dr. Patterson's tutelage

provided the intellectual stimulus that propelled the formation

of smaller workgroups to consider four aspects of libraries where

guidelines could be developed: the environment in which services

are delivered, the programs and services offered, the collections

that are developed and the staff that is employed in the library.

Reassembling, the smaller groups brought proposed

wording back. Revisions by the larger group were considerable.

Work progressed quickly under Lotsee's direction. Directors took

copies of the document to share with their libraries, communities

and Native educational organizations. Feedback was sporadic and

continued to trickle in through the spring of 2001. The changes

that were suggested were forwarded to the entire group through

their listserv. Almost every suggestion that came in improved the

document and was easily incorporated into the wording. By June

the document was completed to almost everyone's satisfaction. That

document is now on the ANKN Web site at ankn.uaf.edu/standards/library.html.

I believe several basic truths about libraries. I

believe that, while books and libraries may have the appearance

and tradition of a fundamental component of a white, European,

imperialist institution, their equivalents exist in every culture

in some form. I believe that by taking control of libraries and

filling them with appropriate information, they can be transformed

into institutions that serve people in the villages.

In Alaska, we struggle on two fronts: getting libraries

established in the villages and convincing the state legislature

of the need to support them. Convincing a legislature dominated

by representatives from the major urban areas of the importance

of rural libraries is an uphill battle. It will probably remain

a losing battle without the overwhelming support from the villages.

I'm certain that the importance of libraries will eventually prevail

and they will emerge as a force for cultural, linguistic, historic

and economic independence in the future.

On September 21, 2001 at the State Board of Education

meeting, it was moved by board member Roy Nageak of Barrow to endorse

the Culturally Responsive Guidelines for Alaska Public Libraries.

The endorsement was approved unanimously. Those guidelines are

included for use in your community.

Culturally-Responsive Guidelines

For Alaska Public Libraries

Sponsored by the Alaska State Library

with support and guidance from the Alaska Native Knowledge Network.

(c) Alaska State Library 2001

Preface

The Culturally-Responsive Guidelines for Alaska Public

Libraries were developed by a group of Alaskan library directors*

at a workshop facilitated by Dr. Lotsee Patterson and sponsored

by the Alaska State Library. The goal of the workshop was to develop

guidelines to help public librarians examine how they respond to

the specific informational, educational and cultural needs of their

Alaska Native users and communities. These guidelines are predicated

on the belief that culturally appropriate service to indigenous

peoples is a fundamental principle of Alaska public libraries and

that the best professional practices in this regard are associated

with culturally-responsive services, collections, programs, staff

and library environment.

While the impetus for developing the guidelines was

service to the Alaska Native community, as the library directors

worked on the guidelines it became clear that they could be applied

to other cultural groups resident in Alaska. The guidelines are

presented as basic statements in four broad areas. The statements

are not intended to be inclusive, exclusive or conclusive and thus

should be carefully discussed, considered and adapted to accommodate

local circumstances and needs.

The guidelines may be used to:

-

Review mission and vision statements, goals,

objectives and policies to assure the integration of culturally

appropriate practice.

-

Examine the library environment and atmosphere

provided for all library users.

-

Review staff performance as it relates to practicing

culturally specific behavior.

-

Strengthen the commitment to facilitating and

fostering the involvement of members of the indigenous community.

-

Adapt strategies and procedures to include culturally

sensitive library practices.

-

Guide preparation, training and orientation of

library staff to help them address the culturally specific

needs of their indigenous patrons.

-

Serve as a benchmark against which to evaluate

library programs, services and collections.

Library Environment

-

A culturally-responsive library is open and inviting

to all members of the community.

-

A culturally-responsive library utilizes local

expertise to provide culturally appropriate displays of arts,

crafts and other forms of decoration and space design.

-

A culturally-responsive library makes use of

facilities throughout the community to extend the library's

mission beyond the walls of the library.

-

A culturally-responsive library sponsors ongoing

activities and events that observe cultural traditions and

provide opportunities to display and exchange knowledge of

these traditions.

-

A culturally-responsive library involves local

cultural representatives in deliberations and decision making

for policies and programs.

Services And Programs

-

A culturally-responsive library holds regular

formal and informal events to foster and to celebrate local

culture.

-

Culturally responsive programming involves members

from local cultural groups in the planning and presentation

of library programs.

-

Culturally responsive programming and services

are based on the expressed needs of the community.

-

Culturally responsive programming recognizes

and communicates the cultural heritage of the local area.

-

Culturally responsive services reach out and

adapt delivery to meet local needs.

Collections

-

A culturally-sensitive library provides assistance

and leadership in teaching users how to evaluate material about

cultural groups represented in its collections and programs.

-

A culturally-responsive library purchases and

maintains collections that are sensitive to and accurately

reflect Native cultures.

-

A culturally-responsive library seeks out sources

of materials that may be outside the mainstream publishing

and reviewing journals.

-

A culturally-responsive library seeks local community

input and suggestions for purchase.

-

A culturally-responsive library incorporates

unique elements of contemporary life in Native communities

in Alaska such as food gathering activities and the Alaska

Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) into its collection.

-

A culturally-responsive library encourages the

development and preservation of materials that document and

transmit local cultural knowledge.

-

A culturally-responsive library makes appropriate

use of diverse formats and technologies to gather and make

available traditional cultural knowledge.

-

A culturally-responsive library develops policies

for appropriate handling of culturally sensitive materials.

-

A culturally-responsive library reviews its collections

regularly to insure that existing materials are relevant and

appropriate.

-

A culturally-responsive library collects materials

in the languages used in its community when they are available.

Library Staff

-

The culturally-responsive library reflects the

ethnic diversity of the local community in recruitment of library

boards, administrators, staff and volunteers.

-

A culturally-responsive staff recognizes the

validity and integrity of traditional knowledge systems.

-

Culturally-responsive staff is aware of local

knowledge and cultural practices and incorporates it into their

work. For example, hunting seasons and funeral practices that

may require Native staff and patrons to be elsewhere, or eye

contact with strangers, talkativeness or the discipline of

children.

-

A culturally-responsive staff is knowledgeable

in areas of local history and cultural tradition.

-

A culturally-responsive staff provides opportunities

for patrons to learn in a setting where local cultural knowledge

and skills are naturally relevant.

-

A culturally-responsive staff utilizes the expertise

of Elders and culturally knowledgeable leaders in multiple

ways.

-

A culturally-responsive staff will respect the

cultural and intellectual property rights that pertain to aspects

of local knowledge.

-

Culturally-responsive library staff members participate

in local and regional events and activities in appropriate

and supportive ways.

* These guidelines were developed

by:

Judith Anglin, Ketchikan

Stacy Glaser, Kotzebue

Nancy Gustavson, Sitka

Marly Helm, Homer

Greg Hill, Fairbanks

Ewa Jankowska, Kenai

Tim Lynch, Anchorage

Dan Masoni, Unalaska |

|

Carol McCabe, Juneau

David Ongley, Barrow

Lotsee Patterson, Facilitator

Karen Crane, Director, Alaska State Library

George Smith, Deputy Director, Alaska State

Library

Nina Malyshev, Development Consultant, Alaska

State Library |

Gail Pass Moves On

We have been fortunate throughout the life of the

Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative to have highly talented and dedicated

staff to breath life into the work we are doing. One who has been

with us nearly from the beginning and has provided much of the

glue that holds everything together has been Gail Pass, administrative

assistant at the AFN office of the AKRSI. Gail has provided critical

technical skills essential to keeping track of the many activities

sponsored by the project; she has also been a valuable contributor

to the thinking that has gone into shaping that work. Evidence

of her insightful perspective on the inner workings of the world

in which we live is reflected in a poem found on the back page

of this newsletter, which she has provided as a gift to all of

us on her move to a new position as a financial analyst with Alaska

Communications Systems. The staff of AKRSI want to express our

appreciation to Gail for her faithful service-with-a-smile over

the years and we wish her good fortune as she moves on to new opportunities

in her life. We’ll be calling on you, Gail . . . !

Parenting & Teaching: One and

the Same

by Angayuqaq Oscar Kawagley

Waqaa,

As I begin this article, I am reminded of the Yupiaq

woman who had an irritated skin condition on her hands and was

given a tube of ointment with an applicator. One night when she

was awakened by the irritation, she reached over in the dark to

retrieve the ointment and applied it to her hands. The next morning,

she woke up and looked at her hands. She was astounded and bewildered.

Her hands were completely red. She worried as to what was happening

to her skin. She finally looked at the tube of ointment she had

applied, and then laughed when she saw that it was a red Bingo

dauber!

During the last century or so, we, as parents and

teachers, have been working blindly just as this woman because

of the promises of the American Dream-promises of a quality education,

a good job, a good home, earning top dollars and getting promotions.

We have become Americanized to a high degree. In the process, we

have been losing our Native languages and cultures. A recent newspaper

article suggests that our Native languages are eroding and many

will be gone within a generation. Will we, as parents and teachers,

allow this to happen? Historically the American way has encouraged

the loss of Native languages and cultures. The English language

and its cultures continue to have a very voracious appetite and

will devour our Native languages and cultures if we allow it.

In the past, our children were born in a sod house

or a tent at spring camp or delivered under an overturned skin

boat in an emergency. From the outset the newborn is introduced

to the voices of the family members, the words of the midwife,

the hum of the wind, the sound of falling rain and the call of

the Arctic loon. The newborn is already immersed in nature from

its first moments of life. During the gestation period and after

a given time, the child is talked to, sung to by the mother and

exposed to family members eating, sleeping, doing work and playing.

The child learns of the sounds peculiar to its parents' language,

love and care bringing an indelible sense of belonging. The child

is exposed to and lives within nature all its life. When the mother

walks, the child is placed inside the parka on its mother's back.

The child can then look around and see things from the same level

as its mother and is treated as a beautiful living being.

As the child progresses through its growing stages,

the parents, grandparents and community members assess the talents

and inner strengths the child might have. These are nurtured with

the thinking that the community will become greater with a responsible

and caring member. As the child grows older, the members look for

ideas that the child expresses, skills it shows, its interaction

with others and its respect for everyone and everything.

There are rites of passage that are practiced as

the child grows. The killing of a first mosquito, first pick of

berries and other acts are times of joy by villagers and are reinforced

by giving support and encouragement for continued growth, physically,

intellectually, emotionally and spiritually. Puberty is a time

of ceremony-the becoming of a woman or a man. First menstruation

of a young lady is considered a time of power requiring that the

young lady be housed apart and served only by the mother or grandmother

for its duration. No work is required of her.

As the young person matures, the community members

may ask the youngster: "Have you counted your blessings lately?" In

actuality, they are asking: "Have you counted your inner values,

talents, strengths, important relationships and connectedness?" This

connectedness is spirituality. Knowing this about oneself will

make one beneficial to the community.

With respect to discipline, the home must be a place

of love, care, companionship and cooperation. If these are practiced,

the child is well-behaved. If such ingredients are lacking in the

home, how can the parents expect to discipline the child? If the

home is dysfunctional, then where will the child find the love,

care, attention and companionship they need? It is possible for

a parent to be a teacher, but a teacher cannot really substitute

for a parent, yet this is what we sometimes expect of the school.

When teachers meet with parents, it is important that they encourage

them to be loving, caring and attentive to their child's needs

and then the teacher should reinforce the parents attention.

As educators, we must try to make the classroom an

environment where children can be with and of nature. Take them

outdoors as much as possible. Have the children express their ideas

of what is beautiful that they see in nature; guide them to begin

to see beauty in oneself and in others, in one's village or in

one's neighborhood. The young person will then begin to see the

value of their own Native language and culture. This is an invaluable

asset in one's life. From this, you begin to see that "community/place

is an experience that is created." Quyana

Alutiiq/Unangax Region: Re-establishing

Illuani

by Teri Schneider

Residents of the Kodiak Island area who remember

the oral history magazine Elwani, were delighted to learn about

a new publication that was produced by students through the Kodiak

Island Borough School District. Illuani (same meaning and approximate

pronunciation as the previous title) began to be distributed in

June. Like the previous project, the latest version is a collection

of interviews done of local people by high school students from

our islands' communities. Featured in this latest version are Iver

Malutin, Florence Pestrikoff, Susan Malutin, Ed Opheim, Sr. and

the past coordinator of the project, Dave Kubiak. Students from

Port Lions, Danger Bay, Old Harbor, Akhiok and Karluk completed

the interviews and then worked with their site teachers and project

coordinator, Eric Waltenbaugh, to transcribe the articles and create

introductions. What a success! Not only are students learning writing

skills, they build their skills for listening and communicating

effectively across generations.

A few years ago people began to ask me, "What ever

happened to Elwani? How come we don't see those around anymore?" As

background information was gathered about the first effort, it

became more and more apparent that we could re-establish the project

with a few minor changes. Illuani could become a wonderfully relevant

learning tool while fulfilling the need to document people's knowledge

and experience in our region of the world so that we could continue

to communicate and celebrate the ingenuity and lives of each other.

Like the magazine of the 70s and 80s, the school district is printing

it, but the new one will be done primarily by rural students with

some contributions by interested students in Kodiak.

The night of the first interviews, held at the Alutiiq

Museum in Kodiak, was a marvelous event. The students were nervous

and the invited guests that were to be interviewed were unsure

of their role and of what they might contribute. When the students

went to their designated areas with their tape recorders, note

pads and interviewees, magic happened. The project became a reality

and took on a life of its own. Nobody needed prompting and nobody

needed interventions by teachers. Giggles came from every corner

as each group became engaged in conversation, often times sprinkled

with humor to create a level of comfort for both the students and

adults.

When we gather together with open ears, minds and

hearts we allow ourselves to learn from one another. Perhaps we

learn the value of taking care of your neighbor when we hear someone

tell their story of the '64 earthquake or tidal wave. Maybe we

learn to become more resourceful after hearing a story of how people

used to bake bread on a beach in an oven made of rocks. Or, perhaps

we learn that we never stop learning when we watch an Elder learn

a new skill from a student. When we take the time to visit and

listen we learn that each one of us has something to contribute

to our community. Illuani is an example of students and community

members contributing to each other's lives and in turn sharing

that gift with all of us.

If you are interested in purchasing the new Illuani

magazine you may contact the staff at the KIBSD Central Office

(486-9210). All proceeds will go to supporting the continuation

of the project.

Athabascan Region: Moose Hunting

and More: the Annual Field Trip for the Minto Flats Cultural

Atlas

by Kathryn Swartz, Cultural Heritage

and Education Institute

The

sun was very warm and the sky was clear on the top of COD Hill

on Saturday afternoon, September 22, 2001. A group of Elders and

youth from Minto relaxed on the hill and looked for moose out in

the Minto Flats. From this hill, one could see Denali in the distance

and the ridges where the Nenana and Tolovana Rivers meet the Tanana

River. "Shhhhh . . ." the Elders kept saying, "the animals will

hear you up here." At one point, a raven stalked a juvenile bald

eagle in the air below us. After looking for hours, Susie Charlie

noticed a bull moose off to the east over by a little lake. A small

group went down the hill and up the creek to walk into the area

where the moose had been seen. We heard shots fired-the hunt was

successful! The

sun was very warm and the sky was clear on the top of COD Hill

on Saturday afternoon, September 22, 2001. A group of Elders and

youth from Minto relaxed on the hill and looked for moose out in

the Minto Flats. From this hill, one could see Denali in the distance

and the ridges where the Nenana and Tolovana Rivers meet the Tanana

River. "Shhhhh . . ." the Elders kept saying, "the animals will

hear you up here." At one point, a raven stalked a juvenile bald

eagle in the air below us. After looking for hours, Susie Charlie

noticed a bull moose off to the east over by a little lake. A small

group went down the hill and up the creek to walk into the area

where the moose had been seen. We heard shots fired-the hunt was

successful!

This event was the high point of the annual cultural

atlas field trip with Minto Elders and youth. This year, the field

trip employed seven Elders: Elsie Titus, Lige and Susie Charlie,

Virgil and Vernell Titus, Luke Titus and Gabe Nollner. There were

eleven students from the Minto School (Clinton Watson, Preston

Alexander, Mitchel Alexander, Ezra Gibson, Amber Jimmie, Alanna

Gibson, Carleen Charlie, Janis Frank, Lynnessa Titus, Dolly James

and Justeena Silas), with their teachers Kraig Berg and Ruth Folger

and the participation of Bill Pfisterer (education specialist)

and Kathryn Swartz of the Cultural Heritage and Education Institute.

The Elders were the most important people on the

field trip. They decided where we were going, where we would stay

and coordinated boat space for all the participants and supplies.

They openly shared stories and tales of hunting, fishing, trapping

and growing up in the Minto Flats. The Minto School played a valuable

role in organizing the students, telling them what they needed

to take with them and also supporting the participation of two

teachers. The information gathered on the trip will be incorporated

into the school curriculum as students work on the development

of a cultural atlas for the Minto Flats area (a preliminary version

of the atlas can be viewed online at ankn.uaf.edu/menhti.)

The field trip was held over a weekend and the group

left Minto after school on Friday, September 21, 2001. The group

went in five boats to Virgil Titus' fall camp along Washington

Creek about an hour and a half from Minto. This camp faces to the

east and south and is positioned above the creek in a nice wooded

area. There is a spotting tree and good cranberry patch back in

the woods. The first night everyone gathered around the fire and

the reason for the field trip and the mapping work was explained.

The Elders said they wanted to bring the kids out to learn the

Athabascan way, to learn what they should bring on this kind of

trip and to learn about the good places to hunt. The Elders shared

some stories and memories about growing up in these areas. After

some coaxing, all the kids finally went to bed. At night, the light

from the radar station on Murphy Dome was visible from the camp

and the Northern Lights shimmered.

The

next morning, after breakfast, Bill Pfisterer showed the kids how

to use two cameras to document the places we would visit-one was

a digital camera, the other a standard film camera. The group set

off in boats to go down Washington Creek and up the Tatalina to

begin the hike up COD Hill. The climb was tough, particularly for

the Elders, but everyone made it. Rope was tied off on certain

trees so you could get extra support and pull yourself up the hillside.

The climb down was even worse with a slippery and dusty trail,

but we were on our way to see the moose so no one seemed to mind

the difficult descent. The moose was taken several bends up COD

creek, back through willows and small birch trees in an open, grassy,

swampy area. The participants witnessed field dressing the moose.

Willows were laid down to hold the best cuts of meat, other parts

were strung over the trees to dry while the work continued. The

Elders shared traditional practices and techniques with the students

and then the meat was packed out either with sticks or people put

on raincoats and slung parts over their shoulders. The meat was

left overnight near the river bank braced up with sticks or slung

between trees. (In case anyone noticed the date, the Cultural Heritage

and Education Institute had arranged for a cultural education permit

to take a moose out of season.) The

next morning, after breakfast, Bill Pfisterer showed the kids how

to use two cameras to document the places we would visit-one was

a digital camera, the other a standard film camera. The group set

off in boats to go down Washington Creek and up the Tatalina to

begin the hike up COD Hill. The climb was tough, particularly for

the Elders, but everyone made it. Rope was tied off on certain

trees so you could get extra support and pull yourself up the hillside.

The climb down was even worse with a slippery and dusty trail,

but we were on our way to see the moose so no one seemed to mind

the difficult descent. The moose was taken several bends up COD

creek, back through willows and small birch trees in an open, grassy,

swampy area. The participants witnessed field dressing the moose.

Willows were laid down to hold the best cuts of meat, other parts

were strung over the trees to dry while the work continued. The

Elders shared traditional practices and techniques with the students

and then the meat was packed out either with sticks or people put

on raincoats and slung parts over their shoulders. The meat was

left overnight near the river bank braced up with sticks or slung

between trees. (In case anyone noticed the date, the Cultural Heritage

and Education Institute had arranged for a cultural education permit

to take a moose out of season.)

Saturday night was a beautiful evening with good

food, more stories from the Elders and good laughs around the campfire.

One of the students made cranberry sauce from freshly picked berries.

That night, the temperature dropped and on Sunday morning as always,

the first ones up, Virgil and Vernell Titus, started the fire and

got warm water and coffee going. After breakfast several Elders

including Lige Charlie and Luke Titus thanked everyone for attending

and for the organization of the field trip. We headed back to retrieve

the moose meat and then made our way back up the winding sloughs,

creeks and rivers to Minto. Ducks gathering for migration were

scared up at every turn. The air was colder than it had been on

Friday and it seemed that winter was now on its way.

This field trip was made possible thanks to support

from the Rural School and Community Trust (Alaska Rural Systemic

Initiative), the Minto School, the Alaska Humanities Forum, the

New Voices Fellowship Program and the Skaggs Foundation.

Alaska Native Education Summit 2001

Alaska Natives will soon have an opportunity to share

their views on how to improve education for our children. The first

Alaska Native Education Summit takes place November 30 and December

1 in Anchorage. It's being sponsored by the ANCSA Education Consortium

and the First Alaskans Foundation.

This gathering of Alaska Native voices is the first

step in looking for new ways to teach our young people the values

and knowledge they must have to do well in their lives.

Unlike other meetings in the past, this one will

focus on Alaska Native issues and begin the process to find Alaska

Native solutions. We're looking for new people at the table who

bring important Native perspectives and are willing to work hard

to come up with fresh ideas that meet the needs of our children.

This summit will draw together Native communities to develop plans

that fit their situation and draw on their experience of what works

and what does not. It will truly be a "grass roots" approach to

providing quality education.

The summit is open to the public and we encourage

all who care about this important issue to come and express their

thoughts and perspectives. For more information contact Joan McCoy

at 907-272-0839 or email

nes@nexusnw.com.

Southeast Region: Opening the Box

of Knowledge

by Andy Hope

Southeast

MOA partners and tribal representatives met in Juneau the week

of September 10, 2001 for a tribal watershed/GIS/cultural atlas

workshop, a Southeast Alaska Tribal College organizational meeting

and the planning meeting for the Southeast Native/Rural Education

Consortium. Southeast

MOA partners and tribal representatives met in Juneau the week

of September 10, 2001 for a tribal watershed/GIS/cultural atlas

workshop, a Southeast Alaska Tribal College organizational meeting

and the planning meeting for the Southeast Native/Rural Education

Consortium.

A number of key presenters were not able to make

it to the watershed workshop because of flight restrictions, so

we will try to get the group together again in mid-November.

The group participated in two teleconferences during

the workshop. The first teleconference was with Jane Langill and

Judith Roche of One Reel in Seattle to discuss the I Am Salmon

curriculum project. Following is a brief description of the project:

I Am Salmon: International Educational

Program

A multidisciplinary, multilingual, multicultural,

multinational educational program for educators and children in

salmon cultures around the North Pacific Rim. Following a challenge

from Dr. Jane Goodall in 1994 and an international writing project

held in 1998 with schools in Seattle and Japan (The Neverending

Salmon Tale), an international team of educators met at Sleeping

Lady Conference Center in 1999 and developed a pilot project for

schools in Alaska, Canada, Oregon, Washington, Japan and Russia.

Schools are creating and sharing work in many disciplines on the

theme of salmon in local culture. The multilingual "I Am Salmon

E-Learning Website" launched September 2001. Details can be obtained

at www.onereel.org/salmon.

From First Fish: One Reel's Wild

Salmon Project

One Reel had scheduled The Icicle River Children's

Summit for September 19-23 in Leavenworth, Washington. Teachers

and children from around the North Pacific Rim (including representatives

from Washington State, British Columbia, Alaska, Japan and Kamchatka)

were to meet for the first time to share materials and knowledge

developed over the last two years. This meeting has been postponed,

possibly until late spring of 2002. The Alaska representatives

will be Inga Hanlon, a fifth grade teacher, and two of her students

from Yakutat City School along with Lani Hotch, a high school teacher,

and nine students from Klukwan School.

In the meantime, I will continue to work with our

Alaska I Am Salmon partners to link with One Reel's new website,

http://iamsalmon.org, to offer access to curriculum resources.

Our second teleconference was with Tom Thornton,

who was stranded in Ontario, Canada on September 11. Tom serves

as the director of the Southeast Alaska Native Place Name Project,

which serves as the foundation for the Cultural Atlas project in

which tribes and school districts work in partnership to develop

multimedia educational resources.

I am encouraged by the commitment of our respective

partner school districts: Chatham School District (Klukwan and

Angoon Schools) Hoonah City Schools, Sitka School District and

Yakutat City Schools. Additionally, our tribal partners (Sitka

Tribe of Alaska, Chilkat Indian village, Angoon Community Association

and Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska)

have immeasurably strengthened our effort. Juneau School District

is a valuable partner that continues to support projects like I

Am Salmon. Our next task will be to schedule a staff development

workshop and a GIS consortium meeting to work on various curriculum

projects. We will also begin building an I Am Salmon listserv in

conjunction with the ANKN.

The events of September 11 overshadowed our meetings.

The Southeast Alaska Tribal College organizational meeting was

rescheduled for October. Though we weren't able to formally organize

SEATC at this time, the people that did make it to Juneau decided

to have a work session to develop recommendations for the SEATC

trustees to consider when they finally do meet. The working group

developed the following draft mission statement:

"The mission of SEATC is to open our ancestors box

of wisdom, knowledge, respect, patience and understanding."

The Box of Knowledge serves as the logo for SEATC

as well as a guiding metaphor. In Tlingit, Yaakoosgé Daakakóogu

means "The box of knowledge that will be opened when people come

to this college." I anticipate ten tribes will be founding members

of the SEATC and representatives of those tribes will elect the

board of trustees

Yup'ik Region: Calista Elders Council

Expands Services

by Mark John, Executive Director,

Calista Elders Council, Inc.

Just recently, I moved my office to Bethel to be

able to work more closely with the Elders and youth in our region.

I have enjoyed visiting with people who have dropped by my office

to see who we are, what we are doing and what we plan to do. There

has been some confusion between Calista Corporation and Calista

Elders Council (CEC), so I would like to provide some background

about CEC.

The Calista Elders Council was incorporated on March

27, 1991. It was formed pursuant to a shareholders mandate during

the 1990 Calista annual meeting held in Kasigluk. The CEC was established

to promote the needs of and serve the special interests and concerns

of the Calista shareholders ages 65 and older.

The Calista Elders Council is a 501c(3) non-profit

organization regulated under state and federal laws. This makes

Calista Elders Council an independent entity with its own articles

of incorporation and by-laws and its own board of directors. The

objectives embodied in the mission statement include:

-

Enhance Elder benefits within the Calista region

by striving to maintain and preserve the cultural, linguistic

and traditional lifestyles of the Natives of the region,

-

Improve the health and welfare of the Elders,

-

Facilitate infrastructure important in providing

for Elder care,

-

Encourage and enhance the participation of Elders

in the political process,

-

Foster and encourage the education of young people

within Calista region.

Our major funding comes from grants. Currently, we

are operating under a number of grants from different sources including

the following:

-

A five-year grant from the National Science Foundation

for $1,087,975 to gather, preserve and share Yup'ik "way of

being."

-

A two-year grant from U.S. Department of Housing

and Urban Development Drug Elimination Program for $695,760

under sub-recipient agreement with Calista Corporation.

-

A one-year Historic Preservation Fund grant in

the amount of $50,000 from the National Park Service, under

sub-recipient agreement with Calista Corporation.

-

A one-year Administration for Native Americans

grant in the amount of $124,909 for Yup'ik Foundation Word

Dictionary.

-

An annual grant of $50,000 from Calista Corporation

for administration and overhead, plus use of office space and

office equipment and supplies in Anchorage.

-

An equipment grant from Rasmuson Foundation in

the amount of $25,000.

Additional funding in various amounts has been received

from the following organizations:

-

Administration for Native Americans

-

Alaska State Council on the Arts

-

Alaska Humanities Forum

-

Coastal Villages Region Fund

-

Exxon

-

Various businesses and village organizations

The primary focus of our efforts has been the documentation

and strengthening of Yup'ik culture. When I went out to do a very

brief survey of activities that are related to our mission in the

winter of 1997 and 1998, culture and history was one area where

there was a clear void. We began to make efforts to fill that void

and make culture and history CEC's niche in the region.

Calista Elders Council has been successful in obtaining

grants to hold three annual Elders and youth conventions, sponsor

culture camps over two summers with a subsistence focus in the

Coastal, Kuskokwim and the Yukon areas of the Calista/AVCP region

and hold topic-specific gatherings of Elders to collect knowledge

on information related to our Yup'ik culture for the past two years.

All of the valuable information gathered from our Elders during

these events are documented, transcribed and translated. In the

very near future, we are looking forward to having publications

available in the form of books and a newsletter.

Throughout the past year, Calista Elders Council

staff has made a number of presentations to different conferences

and conventions related to the preservation of culture and history.

Some of these were the CEC Elders and Youth Convention, Bilingual/Multicultural

Education and Equity Conference, Anchorage, Northern Studies Conference

at Hokkaido University in Japan and the National Science Foundation

Arctic Social Science Planning Workshop in Seattle, Washington.

We feel a sense urgency to focus our work on culture

and history, because many of our Elders that are 65 and older are

passing on. They are the ones with first hand knowledge of our

traditional lifestyle. They were born before Western influence

from the schools and the churches made a big dent in our traditional

way of living. They experienced the ceremonies and spiritual activities,

dances, subsistence practices, our value systems, stories, semi-nomadic

lifestyle, relationships, arts and crafts and everything else that

was associated with our culture. We will continue to work with

them to gather knowledge that is so valuable.

Subsistence was the main focus of our camps. This

summer Calista Elders Council ran four ten-day culture camps in

the region. The first one was at Umkumute on Nelson Island from

June 3 to June 13 for the coastal villages; the second was from

June 17 to June 27 near Akiak for Lower Kuskokwim villages; the

third was near Kalskag from July 1 to July 10 and the fourth was

held July 15 to July 25 between Pilot Station and Marshall for

Yukon villages. We requested participation by a boy and a girl

from each of the 48 occupied villages in the region. We had an

Elder as an instructor for every five students in each camp, along

with staff to document cultural information and provide camp support.

The camps incorporated two age groups: Village Elders

who served as the camps' teachers and mentors and sixth- and seventh-grade

youth who were attending the camps to learn Yup'ik/Cup'ik cultural

skills, history and values. Subsistence hunting, fishing and harvesting

activities appropriate to each camp location were the focus of

the camps, providing the Elders an opportunity to pass down traditional

skills and values.

This summer Chris Dock from Kipnuk ran the summer

camps. He did an excellent job and worked very well with the Elders,

youth and staff as well as communities that were involved. Chris

stated that he enjoyed the experience and he was very grateful

for the help that the Elders and the camp staff provided. Congratulations

to Chris and all who were involved for a successful camp season

and a big quyana from all of us.

This fall, we are going to continue to document traditional

knowledge. We plan to have a topic-specific gathering in November

with selected Elders, the culture coordinators and the drug elimination

project staff from the villages.

The CEC board decided to schedule the annual meeting

and convention in Akiachak in March of 2002 rather than in November

when it has previously been held. The reasons cited were bad weather

and poor travel conditions normally experienced in the fall. The

past conventions were held at Kasigluk in 1998, St. Mary's in 1999

and in Toksook Bay in 2000.

Calista Elders Council board and staff are very proud

of the progress we have been able to make in a short time and we

plan to continue to make efforts to expand our work in the area

of culture and history. In the future we plan to provide more services

to the Elderly and the youth and collaborate with other organizations

with similar activities whenever possible.

Calista Elders Council has made Bethel the base of

our operations. We are expanding our staff in Bethel. We will continue

to have an office in Anchorage and employees that will work out

of their homes in the Anchorage area. We will also hire culture

coordinators that will be located in the villages to work with

clusters of communities within the region. We are aware that CEC

has an excellent potential for growth and we will strive to continue

that growth to provide cultural activities as well as services

that are needed for our Elderly and youth.

I would like to say quyana to our board, who have

contributed valuable knowledge and wisdom. They are Paul Kiunya,

Sr., chairman; Bob Aloysius, vice-chair; John A. Phillip, Sr.,

secretary; Peter F. Elachik, treasurer and Nick Andrew, Sr., Winifred

Beans, Irvin C. Brink, Sr., Peter Jacobs, Sr., Paul John, Fred

K. Phillip, Andrew J. Guy and Myron P. Naneng, Sr. as board members.

I also would like to extend a very big thank you

to both our Anchorage and Bethel based staff. They are Nicholas "Bob" Charles,

Jr., program manager; Alice Rearden, transcriber/translator; Dr.

Ann Fienup-Riordan, consultant; Monica Sheldon, oral historian;

Chris Dock, camp coordinator and Elena Chief, gaming. Without their

support, we would not be where we are. Quyana caqneq!

We wish all of you good health and success in your

subsistence activities. We can be contacted at P.O. Box 2345, Bethel,

Alaska 99559 or at 301 Calista Court, Suite A, Anchorage, Alaska

99518. Our contact numbers are 907-543-1541 in Bethel or 1-800-277-5516

in Anchorage.

One Among Others

by Gail Pass

See yourself as one among others,

See children, fathers and mothers.

Acceptance of who you are in a crowd

in amongst us, not above on a cloud.

The difference of one in a crowd can make,

little bits of change, opportunities to take.

Learn from me as I learn from you,

allow lessons in life to change you.

|

|

Individualize all, humble your

heart,

You generalize a nation, hatred you start.

This hatred you breathe, fear and detest,

born from the compounds of vanity at best.

Tolerate us, a nation of all flavors,

respect family, friends and neighbors.

See yourself as one among others,

See children, fathers and mothers. |

Alaska RSI Contacts

Co-Directors

Ray Barnhardt

University of Alaska Fairbanks

ANKN/ARSI

PO Box 756730

Fairbanks, AK 99775-6730

(907) 474-1902 phone

(907) 474-5208 fax

email: ffrjb@uaf.edu

Oscar Kawagley

University of Alaska Fairbanks

ANKN/ARSI

PO Box 756730

Fairbanks, AK 99775-6730

(907) 474-5403 phone

(907) 474-5208 fax

email: rfok@uaf.edu

Frank W. Hill

Alaska Federation of Natives

1577 C Street, Suite 300

Anchorage, AK 99501

(907) 263-9876 phone

(907) 263-9869 fax

email: fnfwh@uad.edu |

Regional Coordinators

Andy Hope

Southeast Regional Coordinator

8128 Pinewood Drive

Juneau, Alaska 99801

907-790-4406

E-mail: andy@ankn.uaf.edu

Branson Tungiyan

Iñupiaq Regional Coordinator

PO Box 1796

Nome, AK 99762

907-443-4386

E-mail: branson@kawarak.org

Teri Schneider

Aleutians Regional Coordinator

Kodiak Island Borough School District

722 Mill Bay Road, North Star

Kodiak, Alaska 99615

907-486-9276

E-mail: tschneider@kodiak.k12.ak.us

John Angaiak

Yup’ik Regional Coordinator

AVCP

PO Box 219

Bethel, AK 99559

E-mail: john_angaiak@avcp.org

907-543 7423

907-543-2776 fax |

Sharing Our Pathways is a publication

of the Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative, funded by the National

Science Foundation Division of Educational Systemic Reform

in agreement with the Alaska Federation of Natives and the

University of Alaska.

We welcome your comments and suggestions and encourage

you to submit them to:

The Alaska Native Knowledge Network

Old University Park School, Room 158

University of Alaska Fairbanks

P.O. Box 756730

Fairbanks, AK 99775-6730

(907) 474-1902 phone

(907) 474-1957 fax

Newsletter Editor: Dixie

Dayo

Layout & Design: Paula

Elmes

Up

to the contents Up

to the contents

|