|

Sharing Our

Pathways

A newsletter of the Alaska Rural Systemic

Initiative

Alaska Federation of Natives / University

of Alaska / National Science Foundation

Volume 7, Issue 4, September/October 2002

In This Issue

WIPCE 2002 Alaska participants

peek out the door of a teepee after dance practice. Top

L to R: Olga Pestrikoff, Lolly Carpluk, Virginia Ned,

Bernice Tetpon, Caroline Tritt-Frank. Bottom L to R:

Florence Newman, Yaayuk Alvanna-Stimpfle, Nita Rearden,

Cecilia Martz, Julie Kangin. |

Who is this child named WIPCE?

by Ac’arralek Lolly Sheppard

Carpluk

Who is this child named WIPCE (pronounced wip-see)?

It is the coming together of the youth, youthless (in-betweens)

and Elders of the world’s indigenous peoples, according to

its founder, Dr. Verna J. Kirkness. The very first World Indigenous

Peoples Conference on Education (WIPCE) was held in North Vancouver,

British Columbia, Canada in 1987. The 1987 conference theme was "Tradition,

Change and Survival." Tradition represented by the past and

the Elders; Change represented by the present and the youthless

and Survival represented by the future and the youth. There were

participants from 17 countries, with a total of 1,500 people attending

the 1987 WIPCE.

Dr. Verna J. Kirkness equated WIPCE to being a child

who was born in Xwmelch’sten, North Vancouver, Canada–a

difficult and laborious birth, she recalls. From there WIPCE was

nurtured and suckled at Turangawaewae Marae, Aotearoa (New Zealand)

in 1990 on its third birthday and then on to Wollongong, Australia

for its sixth birthday in 1993. WIPCE’s ninth birthday was

spent in arid Albuquerque, New Mexico in 1996 and in 1999 WIPCE

was really happy to spend its twelfth birthday in Hilo, Hawai’i.

This year’s host for WIPCE’s fifteenth birthday was the

First Nations Adult and Higher Education Consortium (FNAHEC). The

conference drew 2500 people to the beautiful site of Stoney Park

on the Nakoda Nation Reserve near Morley, Alberta, Canada.

I had no idea what to expect when I attended my first

WIPCE in Albuquerque in 1996. I had no clue that I would share

similar struggles in education with like-minded indigenous peoples

who soon became friends from across the world. Little did I expect

to network with indigenous people who had developed models of education

and a way of thinking that were the beginnings of turning indigenous

education around. Little did I expect to participate in celebrations

of who we are as indigenous peoples with dancing, singing and,

most important of all, the sense of humor that pulls us through

all of life and its challenges. All this happened and more.

The sharing of models and ideas flourished with the

attendance of over 5000 people at the Fifth World Indigenous Peoples

Conference on Education hosted by the Hawaiians in Hilo, Hawaii

in 1999. So, too, the networking and connections continued with

the Sixth World Indigenous Conference on Education in Stoney Park.

The WIPCE 2002 mission statement stated that we would celebrate "the

sharing and promoting of indigenous-based initiatives by featuring

holistic educational efforts to maintain and perpetuate our ways

of knowing and to actualize the positive development of indigenous

communities."

Elder Julie Kangin giving

her presentation at the “virtual teepee”. WIPCE

2002, Stoney Park, Calgary, Alberta. |

The conference objectives supported the mission statement

by providing a means for indigenous nations to honor their cultures

and traditions by recognizing, respecting and taking pride in respective

unique practices. The conference opening and closing ceremonies,

the daily sunrise ceremony, the evening cultural exchanges and

performances and the many workshops provided the means to achieve

these valuable experiences. In addition, the conference provided

a continuation of dialogue and action around educational issues

that indigenous nations face, as well as a forum for international

exchanges and the promotion of experiential teachings that actively

involved all conference participants.

We honored and recognized the teachings of our Elders

by incorporating their experiences in the various workshops and

activities. The conference organizers sought to strengthen and

continue the WIPCE legacy that indigenous peoples gain greater

autonomy over their everyday lives and strive to overcome the effects

of colonialism. Presenters were encouraged to share how they are

implementing the provisions articulated in the Coolongata Statement

on Indigenous Rights in Education that was adopted at the 1999

WIPCE in Hilo.

FNAHEC was founded on the belief that the realization

of cultural identity is essential to the development of the self-actualized

person. So it was their intention that hosting the world conference

would enable them to "bring about greater unity and co-operative

action to make our world the place that our creator intended it

to be." The conference brought educators together from around

the world to provide opportunities for collaborative initiatives.

A challenge in hosting the conference was to make the circle larger

by bringing representatives from countries that had not previously

participated. Thus the conference included people from Central

America and Samiiland.

The WIPCE 2002 logo was drawn by Allen B. Wells from

the Kainai Blood Nation in Alberta. His logo captured the proud

spirit of First Nations heritage and the attainment of education.

The peace pipe stood as a spiritual symbol of our cultural beliefs,

a gift from the Great Spirit. Within the circle was a teepee, the

meeting and learning place from which emanates the knowledge for

living that is passed on from generation to generation. The mountains

in the background represented the spiritual essence of our culture.

They also formed the beautiful backdrop for the chosen venue of

WIPCE 2002–the land of the Nakoda Nation. The feathers represented

the four seasons flowing in perpetual motion–the Circle of

Life. Also, embodied within the meaning of the feathers is the

Great Spirit above whom has blessed us with spiritual, mental,

physical and emotional balance to live in harmony within His creation.

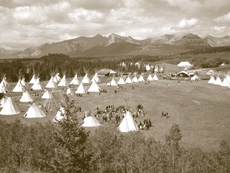

Workshops and presentations

were held in over 60 teepees sprawled out over a field

at WIPCE 2002 in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. |

WIPCE 2002 began on a cold, gray day nestled in a

clearing surrounded by poplar and pine trees, with the majestic

Rocky Mountains in the background and the beginnings of the Bow

River as it flowed from the mountain range out into the prairie

lands that surround Calgary. We, from many international indigenous

nations, huddled together for warmth on bleachers as we listened

to the opening ceremonies. The largest contingencies came from

Hawai’i and Aotearoa, with more than 100 from each nation.

There were about 30 people from Alaska, a majority of whom are

involved with the Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative, either as employees

or memorandum-of-agreement (MOA) partners.

On Monday, Tuesday and Friday, workshops and presentations

were held in over 60 teepees sprawled out over a field that is

also gopher and grasshopper habitat. We either walked or rode on

golf carts from the entrance to our destinations. Most of the teepees

had no electrical outlets which presented a challenge for those

who came with Powerpoint presentations or had planned to use transparencies.

As a result, we truly relied on traditional methods of sharing

through our oral tradition. It made for a startling jolt from the

taken-for-granted modern technology that we have become accustomed

to. But by the end of the week everyone was comfortable with this

type of presenting, because it seemed to encourage more interaction.

We were taken to a time where we had to listen with our ears, eyes,

minds, hearts and souls.

The Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative representatives

and MOA partners put on a joint presentation with a delegation

of Native Hawaiians from the Kahuawaiola Teacher Education Program

in Hilo. This presentation was held in a virtual teepee (outdoors

on the ground), and it was appropriate since it accommodated a

large audience. Part of the Alaskan group held a dance practice

in one of the teepees before the joint presentation, as we didn’t

want to be out-done by the Hawaiians with traditional dances. Yaayuk

Alvanna-Stimpfle and Nita Rearden each lead an Iñupiaq and

a Yup’ik dance, respectively. Over the last two years there

has been an intense exchange and networking between the Alaskan

and Hawaiian Native education groups around the development of

cultural standards, which was the theme of our three-hour presentation.

This is a great partnership that is sure to continue with the development

and exchange of models and ideas to improve education.

A group of us attended a workshop presented by Graham

Smith of the University of Auckland in which he shared recent developments

among the Maori in Aotearoa (New Zealand). He discussed at length

a theory of transformative action during which he shared that the

Te Kohanga Reo (language nests) served as a flagship for a new

mindset of indigenous peoples realizing that the movement to integrate

indigenous language and culture was an affirmation of self-determination.

As indigenous peoples we are cognizant that our languages and cultures

are parallel to and on par with those of the colonizers and thus

we do not need external endorsement that our culture is valid and

something we should be proud of. This realization has now reached

to all levels of education and is having an impact on everything

from infant to tertiary (postsecondary) institutions.

Another presentation that we attended was lead by

Pita Sharples of Auckland, Aotearoa. He presented a rationale and

strategy for the development of a Maori Education Authority, where

there would be a Maori education minister with joint responsibility

for the coordination of all Maori education programs. He wanted

feedback from the audience on this concept as a way to exercise

greater self-determination and to increase Maori control over Maori

education.

Virginia Ned and I led a workshop on "Promoting

an Indigenous Perspective in Research." I discussed my personal

journey in becoming an indigenous researcher, with help from the

timely work and publications by Linda Smith of Auckland, Aotearoa

and Marie Battiste of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. I discussed the

benefits of doing a community research assessment and how I would

like to go about it. I believe each Native community is at a different

level in their journey to accepting research from an indigenous

perspective. Virginia presented her preliminary study of research

that has been conducted in the Interior Athabascan region. The

results from her study are extensive and very interesting and should

be shared with Native peoples throughout Alaska. All the participants

were interested in finding out more about further work on indigenous

perspectives in research.

On Wednesday and Thursday, we had the opportunity

to participate in cultural and educational tours. A group of us

went on the Siksika (Blackfoot) Nation tour. We went onto a reserve

that was 20 by 80 miles in size. Our tour was opened with a prayer

before we visited historic sites, including a memorable visit to

the site where Treaty Number 7 was signed. The significance of

the setting was felt spiritually and moved a group of Maori who

were on the same tour to lead a prayer and blessing. We were treated

to a wonderful feast and powwow.

WIPCE 2002 gave birth to a new organization, the

World Indigenous Nations Higher Education Consortium (WINHEC).

The declaration establishing WINHEC states that, "as indigenous

peoples of the world, we recognize and reaffirm the educational

rights of all indigenous peoples, and we share the vision, united

in the collective synergy of self-determination through control

of higher education" (see sidebar at right). The members of

the consortium are also committed to building partnerships to pursue

common goals through higher education. This was a historic moment,

bringing together indigenous higher education representatives from

all the indigenous regions represented at the conference to support

the creation of this new organization.

The concluding comments by the five representatives

of past WIPCE organizing committees gave us a clearer picture of

what WIPCE has been and will continue to be–the rebirth of

indigenous peoples realization that our language and culture will

always define who we are, and it is our right and responsibility

to make sure this is passed on to future generations. Thus it was

appropriate that Dr. Verna Kirkness equated WIPCE with a child,

for the rebirth of indigenous peoples education began with the

infant in the language nest and has grown to nurture the full potential

of our children and their parents as we move through the different

stages of development and grow into those who will become our future

Elders. For that child, it has been a time of celebrating learning,

celebrating cultures, celebrating our ancestors, celebrating who

we are and celebrating our goals and aspirations. As Verna pointed

out, it has also been a time to share our knowledge, a time to

give thanks to the Creator and even a time of romance, not only

among the young but among the old(er) as well.

That child’s image has been molded by each nation

that has hosted the conference, helping us to continually discover

new ways to move beyond being merely guests in someone else’s

educational system. We need to better define who we are and continue

to highlight what is indigenous about WIPCE. As the Elders have

taught us, it is important to take good thoughts with you and leave

the bad thoughts in the snow, so that come springtime they may

be reborn into good thoughts. Dr. Bob Morgan of Australia pointed

out that Elders are our pathway to the past and the youth are the

custodians of the future. As the WIPCE child has grown, there have

been themes of cultural affirmation by performances and ceremonies;

exchange of ideas and materials where we learn from each other

and develop connections between and among nations, strengthening

and reinvigorating ourselves in an open forum, networking and sharing

so that the whole becomes greater than the sum of its parts, celebration

and renewal for all to love being indigenous and thankfulness that

we are going home with full hearts to take the learning and growth

to our families.

In looking to the future of the WIPCE child, Verna

Kirkness encouraged holding youth forums, emphasizing that we need

to do more for our youth so they know that we now have new instruments

by which we can reinvigorate our educational agenda. We can create

a path of harmony for our young people and we can create institutions

that celebrate our advocacy for indigenous education. We are fortunate

to have our Elders who can guide us in our return to our traditional

language, laws, values, beliefs and rituals that will be at the

center of the rebirth, rebuilding and recreating of our institutions

for tomorrow.

As this year’s theme stated, the answers are

going to have to come from within us. Our traditions will show

us how to cleanse our souls and our minds to deal with finding

the answers. Harold Cardinal reminded us that we have to look deep

within ourselves as we revisit our past to create the most successful

institutions for our future, so they will bring harmony to our

nations, as well as to the rest of the world.

The Maori of Aotearoa were selected to host the 2005

WIPCE. There was an eruption of celebrations as this news was shared.

It is appropriate that the WIPCE child return to Aotearoa, since

the Maori have created models of education for the whole child.

We will try our very best to be patient for the year 2005 to arrive,

when we can all join in another open forum of renewal and celebrations.

I would like to thank the Nakoda Nation and FNAHEC,

on behalf of the Alaska contingency, for the wonderful and loving

care you shared with us in hosting WIPCE 2002. As I was leaving

the bus that took a small group of us to the Calgary airport, the

nine year old girl that accompanied her mom (who was the bus driver)

gave me a pin that said, "Make the Circle Stronger." So,

as the WIPCE logo incorporates the Circle of Life, may we continue

to be blessed with spiritual, mental, physical and emotional balance

as we live in harmony with all creation.

WINHEC Formed At WIPCE

by Merritt Helfferich

AIHEC, CANHE/Alaska, New Zealand, Australia and Canada

representatives established the new World Indigenous Nations Higher

Education Consortium (WINHEC) at the World Indigenous Peoples Conference

on Education (WIPCE) in Stoney Park, Alberta. The WINHEC was started

with a pledge of NZ$500,000 for the first year. The W. K. Kellogg

Foundation will consider a grant of $200,000 for the planning and

initial operation activities of WINHEC. The declaration that was

signed by WIPCE delegates to establish WINHEC is as follows:

Declaration On Indigenous

People’s Higher Education

On this day, August 5, 2002, at Kananaskis

Village, Alberta, Canada, we gather as indigenous peoples

of our respective nations recognizing and reaffirming the

educational rights of all indigenous peoples. We share

the vision of indigenous peoples of the world united in

the collective synergy of self determination through control

of higher education. We commit to building partnerships

that restore and retain indigenous spirituality, cultures

and languages, homelands, social systems, economic systems

and self-determination.

We do hereby convene the World Indigenous

Nations Higher Education Consortium. This consortium will

provide an international forum and support for indigenous

peoples to purse common goals through higher education.

By our signatures, we agree to:

- Accelerate the articulation of indigenous

epistemology (ways of knowing, education, philosophy,

and research);

- Protect and enhance indigenous spiritual

beliefs, culture and languages through higher education;

- Advance the social, economical, and political

status of indigenous peoples that contribute to the well-being

of indigenous communities through higher education;

- Create an accreditation body for indigenous

education initiatives and systems that identify common

criteria, practices and principles by which indigenous

peoples live;

- Recognize the significance of indigenous

education;

- Create a global network for sharing knowledge

through exchange forums and state of the art technology

and

- Recognize the educational rights of indigenous

peoples.

In the spirit of ancestors and generations

to come, we hereby affix our signatures below: [signed

by over 100 WIPCE participants] |

The initial signing took place at a ceremony outside

the Delta Lodge in Kananaskis Village, Alberta where signatures

were affixed to the charter document while it lay on the ground

to mark the indigenous peoples interdependence with the earth.

After prayers, members of the interim executive committee named

at the meetings signed the document while about 30 Maori sang songs

in the background. Following the signing, there were additional

prayers and a lot of hugs and cheers!

Draft Guidelines for Cross-Cultural

Orientation Programs Developed

by Ray Barnhardt

Adraft set of guidelines has been developed addressing

issues associated with providing a strong cultural orientation

program for educational personnel new to a particular cultural

region or community.

The guidelines are organized around various areas

of responsibility related to the implementation of cultural orientation

programs, including those of communities, administrators, professional

educators, tribal colleges and universities, statewide policymakers

and sponsors of cultural immersion camps. Native educators from

throughout the state contributed to the development of these guidelines

through a series of workshops and meetings associated with the

Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative.

The guidance offered is intended to encourage schools

to strive to be reflections of their communities by incorporating

and building upon the rich cultural traditions and knowledge of

the people indigenous to the area. It is hoped that these guidelines

will encourage school personnel to more fully engage communities

in the social, emotional, intellectual and spiritual development

of Alaska’s youth. Using these guidelines will expand the

knowledge base and range of insights and expertise available to

help communities nurture healthy, confident, responsible and well-rounded

young adults through a more culturally-responsive educational system.

Along with these guidelines are a set of general

recommendations aimed at stipulating the kind of initiatives that

need to be taken to achieve the goal of more culturally-responsive

schools. State and federal agencies, universities, professional

associations, school districts and Native communities are encouraged

to sponsor cultural orientation programs and to adopt these guidelines

and recommendations to strengthen their cultural responsiveness.

In so doing, the educational development of students throughout

Alaska will be enriched and the future well-being of the communities

being served will be enhanced.

Following is a summary of the eight areas of responsibility

around which the draft Guidelines for Cross-Cultural Orientation

Programs are organized. The details for each area will be finalized

at the statewide Native Educators Conference in February and published

in a booklet form. The complete set of draft guidelines including

indicators is available on the ANKN web site at www.ankn.uaf.edu.

Draft Guidelines for Cross-Cultural

Orientation Programs

- Culturally-responsive communities, tribes and

Native organizations provide a supportive environment to assist

new members in learning about local cultural practices and traditions.

- Culturally-responsive school districts and administrators

provide support for cross-cultural orientation programs for district

staff and for integrating cultural considerations in all aspects

of the educational system.

- Culturally-responsive educators are responsible

for seeking guidance in providing a supportive learning environment

that reinforces the educational well-being of the students in

their care in a manner consistent with local cultural beliefs,

practices and aspirations.

- Culturally-responsive schools must be fully engaged

with the life of the communities they serve and provide ample

encouragement, support and resources for all staff to integrate

the local cultural and physical environment in their work.

- State policymakers and educational agencies should

provide a supportive policy, program and funding environment

that promotes the establishment of cross-cultural orientation

opportunities for all personnel associated with schools.

- Tribal colleges and universities are responsible

for partnering with communities and schools to provide every

educator with the cultural understandings and educational strategies

necessary to nurture all youth to their full intellectual and

cultural potential.

- Cultural immersion camps should provide an authentic

and supportive environment in which participants gain first-hand

experience interacting with local people while learning the cultural

traditions and lifeways of the area.

General Recommendations

The following recommendations are offered to support

the effective implementation of the above guidelines for cross-cultural

orientation programs.

- Regional Native educator associations should pursue

funding to implement an appropriate cultural orientation program

to serve the needs of the school districts (and other organizations)

in their respective region, including a cultural immersion camp

and follow-up activities during the school year.

- The Consortium for Alaska Native Higher Education

should encourage its member institutions to develop an academic

support structure for cross-cultural orientation programs in

each region, including provisions for academic credit and a system

for assessment of cross-cultural expertise.

- The First Alaskans Institute, in collaboration

with CANHE, should sponsor a training program for personnel associated

with planning and implementing cross-cultural orientation programs.

- Local communities and tribal organizations should

sponsor local and regional cultural orientation programs as needed

to prepare all outside personnel to work effectively with people

in ways that are compatible with local cultural ways and respectful

of the local heritage.

- The Alaska Department of Education and Early Development

should provide incentives and secure continued funding for school

districts to incorporate cultural orientation programs into the

annual district inservice schedule.

- School districts should sponsor opportunities

for students and teachers to participate regularly in cultural

immersion camps with parents, Elders and teachers sharing subsistence

activities during each season of the year.

- The guidelines outlined above should be made an

integral part of all professional preparation and cross-cultural

orientation programs for educators in Alaska.

- An annotated bibliography of resource materials

that address issues associated with these guidelines will be

maintained on the Alaska Native Knowledge Network web site (www.ankn.uaf.edu).

Comments and suggestions for the improvement of these

draft guidelines are welcome and may be submitted to ANKN at the

web site address listed below. Further information on issues related

to the implementation of these guidelines, as well as copies of

the guidelines when they are completed, may be obtained from the

Alaska Native Knowledge Network, University of Alaska Fairbanks,

Fairbanks, AK 99775 (http://www.ankn.uaf.edu).

Native Leaders/Master Teachers

by Bernice B. Tetpon

Beginning in April 2002, the Native Educator Associations

in the five language/cultural regions collected applications and

selected one lead/master teacher for each region. All of these

highly motivated teachers are curriculum developers and culture

bearers in addition to having reputations as long-standing and

highly respected educators.

We are pleased to have these dynamic Native educators

with the Teacher Leadership Development Project. The Alaska Rural

Systemic Initiative in collaboration with the Department of Education & Early

Development made it possible to provide full-time salaries for

these additions to the staff. The group met August 27—29 in

Juneau to develop action plans for their respective regions with

the major focus on implementing the Alaska Standards for Culturally-Responsive

Schools and related cultural guidelines.

We are happy to have the following lead/master teachers

working with us:

Alutiiq/Unangan region: Olga Pesterikoff

and Teri Schneider (tschneider@kodiak.k12.ak.us)

Athabascan region: Linda Green (linda@ankn.uaf.edu)

Iñupiaq region: B.Yaayuk Alvanna-Stimple

(yalvanna@netscape.net)

Yup’ik region: Esther Ilutsik (fneai@uaf.edu)

Southeast region: Angela Lunda (lundag@gci.net)

We will be providing more information on what each

region is doing through the Teacher Leadership Development Project

in future editions of Sharing Our Pathways.

ANSES Corner (formerly AISES Corner)

by Claudette Engblom Bradley

Elder Elizabeth Fleagle teaches

traditional values and bead sewing to camp participants. |

For the seventh summer Fairbanks Science Camp was

held at Howard Luke’s Gaalee’ya Spirit Camp in July.

Funds for the camp were provided jo

intly by the College of Rural Alaska and the Alaska

Rural Systemic Initiative. The camp had 15 rural middle school

students from Arctic Village, Nulato, Minto, Manley Hot Springs

and Kiana. The students learned traditional skills and crafts from

Elders and Alaska Native teachers. They did science projects and

developed display boards for their projects. They enjoyed many

recreational activities including the daily chores required by

all students in the camp.

The Elders were Howard Luke, Elizabeth Fleagle, Margaret

Tritt, Bertha Moses, Johnson Moses and Kenneth Frank (elder-in-training).

The certified teachers were Judy Madros, eighth-grade teacher in

Nulato; Caroline Tritt-Frank, (K—1) Immersion Program teacher

in Arctic Village; Rita O’Brien, former science teacher in

Ryan Middle School and Fort Yukon; Todd Kelsey, a former chemistry

teacher and a current IBM employee and Claudette Engblom Bradley,

UAF mathematics educator. The camp also had four resident advisors

who lived with the students in their tents, helped them complete

their daily chores and assisted them during recreational experiences

and field trips. The resident advisors were David Palmer, Julie

Parshall, Arlo Veetus and Crystal Frank.

Elizabeth Fleagle from Alatna, Manley Hot Springs

and Fairbanks taught the students values and how to sew beads.

They made scissors holders and medicine bags with beaded neck chains.

Elizabeth’s class is very popular among the students and staff.

Margaret Tritt from Arctic Village and Fairbanks

helped the students clean caribou hides and make babiche. Babiche

is sinew. The students used it to make rabbit snares and braid

ties for their small dog packs. Margaret helped the students set

their snares and sew their dog packs. Dog packs were used to carry

essential camping equipment during long travels across the tundra.

Two camp participants work

hard to create fire without matches! |

Bertha Moses and Caroline Tritt-Frank helped the

student make fish nets with weights and floaters. The students

carved the shuttle and measuring gauge in their session with Kenneth

Frank and Johnson Moses. They carried their shuttle and measuring

gauges to Bertha and Caroline’s session. Johnson and Kenneth

helped the students make the weights and floaters for their nets

as well. The students also learned about carving wood from Johnson

and Kenneth. They sewed small nets in the eight-day sessions and

were able to take their work home when the camp was over.

Kenneth and Johnson had the students make survival

gear. They taught them how to start a fire without a match. The

survival gear was made of caribou bones. The gear included a caribou

bone knife, a caribou bone fish hook and a caribou bone arrowhead.

Rita O’Brien helped the students make birch

bark baskets. She showed them where and how to gather the birch

bark and roots for the basket making.

Todd Kelsey flew to Fairbanks to joins the camp for

a week from IBM in Rochester, Minnesota. Todd made the arrangements

with IBM to donate six laptop computers and one color printer to

the camp. He stayed in the camp to insure the computers are used

appropriately and provided the students with instruction on how

to use the printer and computers along with some lessons in chemistry

and mathematics. This year he co-taught his classes with Judy Madros

from Nulato.

The students will further develop their projects

at their school and enter them in local science fairs this fall.

We look forward to seeing them at the statewide ANSES fair in February.

Revisiting Action-Oriented, Multi-Reality

Research

by Angayuqaq Oscar Kawagley

Alaska Native people have often thought of the white

man as having capabilities that go far beyond our own abilities

as creators and inventors, forgetting to consider some of the long-term

side-effects of our infatuation with the Euro-centric ways. That

feeling of awe and wonder is fast changing as we see our world

deteriorate, driving us to action for a change in consciousness

and returning to our own eco-centric worldview.

For the last several centuries, native/tribal people

have been inundated with the products of a materialistic and techno-mechanistic

society. We have marveled at the power of the rational mind and

ingenuity at producing many and varied gadgets that are getting

more complex and thus more difficult to understand and operate.

The Euro-Americans have used the scientific method, objectivity

and reductionism to produce these wonders. They have made gadgets

galore and produced boundless knowledge of the physical universe.

But we should pay heed to the words of Gregory Peck in the movie,

The Snows of Kilimanjaro, when he said, "Just because the

airplane goes faster than the horse does not mean that we are better

off now than we were then." We now suffer from overpopulation,

erosion of natural resources, violence and a loss of faith and

trust in our clergymen, politicians and other institutional leaders.

The Euro-American scientists are coming to the North

in droves to do research in places that they know little or nothing

about, and often fumble around in the dark, almost blindly. Yet

the indigenous people who have lived on this land for millennia

are left out of the research projects in many instances. These

original people who know the history and how to keep their place

sustainable are ignored and seen as being primitive, having only

anecdotal and place-specific knowledge. Native people are led to

believe that they will find the problem and fix it with some form

of new technology. However, there are seldom technological solutions

to biological, mental or spiritual problems.

Western science seeks to identify symptoms of problems

and then develop treatments, whether it involves physical, intellectual,

emotional or spiritual phenomena. This is well and good to a limited

extent, but it has a obvious weakness. These generalized inclinations

have thrust insights drawn from the physical world into a world

of abstractions1. The phenomena studied becomes absorbed by the

generalized approach to solving problems. This outmoded notion

of reductionism and objectivity gets in the way of compassion and

cooperation and denies emotional and spiritual connection between

the human, other creatures, plants and elements of Mother Earth.

However, indigenous people can only be understood as part of their

environment, part of their place.

Early in our heritage as we experienced change, our

Elders recognized that this technical world produced much to purportedly

make life easier, but they also warned that there is a danger in

this trend. Too much of the resources are being used and wasted

and the refining and manufacturing processes involved require excessive

use of energy. In extracting minerals and timber, much land is

laid to waste and it takes a long time for it to recover. These

processes do not take into consideration the needs of the seventh

generation. Will our descendants be able to enjoy the resources

in a similar state of abundance and savor the beauty of Mother

Earth as our ancestors did?

Psychologist Carl Jung has written of the "collective

consciousness" and other scientists have used a holographic

metaphor to convey the complexity of our relationship to our past

and to each other. I can readily appreciate this as it lends itself

to explaining our ancestral memory and ways of knowing. During

gestation in the mother’s womb, a chord is struck which resonates

in the universal holographic mind. Early in life, certain notes

in this chord vibrate stronger than others, such as for suckling,

crying when hungry or hurting, smiling to show love and joy and

so forth. As the child gets older these early notes become weaker

as others become stronger, from which emerges an outgoing personality,

a spiritual attitude, a love of music, a mathematical or scientific

interest and so forth. These will continue to grow while others

begin to shrink as we mature.

There is a story of a hunter about to cross a newly

frozen body of water. He remembers his Elders telling him that

he should test the strength of the newly formed ice by dropping

his ice pick. If it penetrates and does not stop, don’t try

crossing because the ice will be too weak. If the pick stops where

the wooden handle and bone point intersect, the hunter can try

to cross. To do so, he has to gather energy by looking at the sky,

the sun, currents, wind, moon and stars from which he gains a feeling

of lightness in his mind. He starts across the ice establishing

a rhythmic gait, and he makes it to the other side. The energy

chord produced from his observations has struck a resonant chord

in the holographic mind bringing his body in rhythm with the surrounding

environment.

It behooves us, as Native researchers, to redesign

research methodologies that go beyond those we have learned in

the Euro-American universities. We must first try to find balance

in our own lives before we attempt to establish a meaningful and

dynamic relationship with those we are seeking to understand. In

some instances we may have to rely on spiritual methods altogether.

This will allow us to truly interpret data that we have gathered

by asking questions, observing and directly participating in an

experience. We, as Native people, thrive on first-hand experience

as the primary source of knowledge.

We have heard stories about tuberculosis being healed

by drinking juice of the spruce needle, or the remission of cancer

by drinking stinkweed juice. These treatments require belief and

faith from one’s own worldview, using the whole mind and body

to try to explain and understand. If no rational explanation is

found, then one has to accept this on belief and faith of something

greater than you and I. In using this method of knowing it presents

a new frontier of research methods using the whole self. The self

is consciousness without knowing. It has been said that mysticism

is a dialectic of feeling, while science is a dialectic of reason.

We must work toward the integration of the intellectual with the

mystical for the healing process to be complete. Albert Einstein

noted that spirituality is the strongest and noblest motive for

scientific research and as such is a philosophical/psychological

prerequisite for research.

Most research methodologies in vogue today require

that we only use a part of our self. However, the modern scientific

method combined with Native ways has the potential to produce a

new breed of scientists and engineers who are able to exercise

all their capabilities with compassion and a sense of greater purpose

as they strive to build a technology kinder to the human, the environment

and the spirit that resides within all of us. These scientists

will work for restoring balance, healing and living a life that

feels just right. This is action-oriented, multi-reality research

which will put Alaska Native people on a pathway to greater control

of our past, present and future.

Southeast

Region: My Turn Southeast

Region: My Turn

by Ted Wright

As our schools start another year I would like to

send a heartfelt thanks to the many faculty, administrators, staff,

parents and students who have worked tirelessly to provide and

take-part in a first-class education. Thank-you or, in the first

language of Southeast Alaska, gunalcheesh.

While I really do appreciate the progress made toward

better schools and smarter students, much work remains to be done,

so I would also ask policymakers and people in positions of influence

over our educational systems to take time to reconsider the process

and product of schooling. If the kind of education we are providing

is adequate, why does the urban-rural gap seem to be growing? And

why do many of our political and financial leaders seem to misunderstand

the plight of Alaska Natives in general and the importance of subsistence

in particular?

Even among Alaska Natives I wonder about an educational

system that produces leaders who haven’t learned to look several

generations ahead to consider if their decisions are sound, but

instead focuses their attention only on earnings and dividends.

I wonder, for example, if any of the Native leaders who are advocates

of unbridled development have asked their most knowledgeable Elders

about the possible long-term impacts on their people’s way

of life.

At what point did we forget that traditional education–knowledge

about who we are and how we live in a particular place–is

at least as important if not more important to our survival than

a mainstream standards-based education? I know when I forgot–it

was when I went away to earn a graduate degree and stopped hearing

the voice of my grandmother and other Elders. It was when I decided

that a credential bestowed by a prestigious institution was more

important than the truth about the world in which I would live.

It was when I decided that what I do is more important than where

I live and who I am.

It has been hard for many of this generation to redefine

ourselves as Alaskans when we are so unaware of even the basic

facts about who we are in relation to the place we live. In this

respect, our education has failed us and we didn’t even know

it. That is the bad news. The good news is that it is not too late

to change the system for our children and grandchildren.

I have a few suggestions. To start, let’s elect

legislators who will recognize the importance of investing in our

schools and have the foresight to mandate that districts statewide

offer classes in Alaska Studies. Let’s allocate funds to pay

Alaska teachers the best salaries in the country, and then train

them to make their methods and curriculum materials place-based

and culturally relevant. If such training is an option, like an

endorsement in reading, then let’s pay teachers who complete

such training more than those who do not. And at the college level,

support for programs and pedagogies infused with a local and regional

worldview is a good first step. I believe it is possible to not

only keep our kids in Alaska after high school, but also to provide

them with an education that helps them make sense of the complex

issues that we all face now and in the years to come.

The future of Alaska is its children. I would humbly

suggest that to ensure a bright future, we have got to substantially

change our schools. Not only does this kind of change need to begin

now, but it has to begin with each and everyone of us.

Iñupiaq

Region Iñupiaq

Region

Thirteenth Inuit Studies Conference

by Branson Tungiyan

On July 31, 2002 I traveled from Nome to attend the

13th Inuit Studies Conference that was held at the University of

Alaska Anchorage campus. The conference was organized by the University

of Alaska Fairbanks Department of Alaska Native and Rural Development.

The theme for the conference was "Voices from Indigenous Communities:

Research, Reality & Reconciliation".

The conference kicked off with Dr. Gordon Pullar,

the ISC Chair and Lucille Davis, a Sugpiaq Elder, lighting a traditional

seal oil lamp and offering an opening prayer. The welcoming remarks

were given by Chief Paul Theodore from the Knik tribe; Lee Stephen,

the CEO of the Native Village of Ekutna; Chancellor Marshall Lind

from UAF and Provost James Chapman from UAA. Aqqaluk Lynge, president

of the Inuit Circumpolar Conference, gave the keynote address entitled "Science

For and Together with Indigenous Peoples."

Each of the three days had a keynote speaker who

gave interesting presentations. Jose Kusagak, president of Inuit

Tapiriit Kanatami, Canada, was Friday’s keynote speaker; George

Ahmaogak, mayor of the North Slope Borough, Barrow was Saturday’s

speaker.

We also had luncheon speakers. Thursday’s speaker

was Father Michael Oleksa, dean of St. Innocents Cathedral, Russian

Orthodox Diocese of Alaska. He always gives the best presentations

and made everyone laugh throughout his speech. Friday’s luncheon

speaker was Angayuqaq Oscar Kawagley of UAF.

There were some very interesting sessions throughout

the three day conference. I attended workshops on "Issues

in the Arctic," "Traditional Knowledge," "Language

Policy and Usage," "Memory and History" and "Inuit

Spirituality, Values and Culture" as well as a roundtable

discussion on "Comparative Inuit, Yup’ik and Aleut Linguistics." I

also participated in an AKRSI session on "Integrating Indigenous

Knowledge, Ways of Knowing and World Views into the Educational

System." These were all interesting sessions in which issues

and concerns were discussed on the international level and with

an Inuit perspective. The facilitators and presenters did an outstanding

job with their sessions. The conference reminded me of the Alaska

Federation of Natives conventions that we have in Anchorage, but

on the global Inuit level.

Two Elder’s, Lela Oman of Nome and Lucille Davis

of Kodiak, were fabulous in giving their views of the conference

sessions. I enjoyed the part where Lela Oman said that she knew

how to say "thank you" in 12 languages, but the best

one comes from St. Lawrence Island–Igamsiqanaghhalek! Thank

you Lela, as I am from Gambell on St. Lawrence Island. The final

Elder wrap-up was the most enjoyable as they gave their views in

a wonderful fashion. My only wish is that there could have been

more Elders from various places such as Greenland and Canada.

To me, the interesting part of this conference was

meeting the different Inuit and other indigenous people from Canada,

Greenland, France, Germany and New Zealand. The issues discussed–whether

it be education, language, health, environment, or organizational

structures–were very well presented, though time was too short.

We all seem to have so much in common with many of the same issues

that we are concerned about.

Finally, we couldn’t complain about the weather.

Those were the most beautiful days and helped make the conference

that much more interesting and enjoyable. It was just GREAT! I

appreciate the effort that was made in planning for the 13th Inuit

Studies Conference. The organizers did an outstanding job of making

it a success. I felt honored to have been with the group of Inuit

who were in attendance. Thank You!

[The staff of the Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative

extends our sincere thank you and appreciation to Branson for his

contributions as the Iñupiaq Regional Coordinator over the

past two years. He has decided to move back to St. Lawrence Island

this fall to work with his people, so we will miss his wit and

wisdom at our meetings, but we wish him all the best as he takes

on new challenges in his life. Igamsiqanaghhalek for your commitment

to education Branson!]

Youth Empowerment: Traditional Values & Contemporary

Leadership

by Cathy Rexford

April 17—19, 2002, Barrow Alaska.

The First Annual Youth Leadership Conference.

We lift up a new generation of leaders who are grounded

in our Iñupiaq values. During the three-day event, high

school students from across the North Slope discovered that the

key to success in leadership is Iñupiaqatigiigñiq

(Iñupiaq values). As we focus on cultural identity in leadership,

we raise the status of our Native way of life and further revive

traditional values in contemporary Iñupiaq leadership. The

connection between positive self esteem, cultural respect and leadership

was stressed in the conference theme, "Empowering Our Youth

Through Positive Leadership." The message was strong throughout

the conference: "Know who you are, respect yourself, know

where you come from, respect and remember the Iñupiaq people

you serve. Be strong and proud of your place in our communities."

Elders, experienced community leaders, along with

young up-and-coming leaders shared their knowledge and gave encouragement

to the students. The combination of panel presentations and student

action oriented work sessions gave the students the knowledge they

need to make a difference and a forum to contribute to the health

of their schools and communities. The youth raised their voices,

and what we heard from these young people was a new generation

of Iñupiaq leaders who will look with hope to the future

while learning from the past. These students worked long and hard

hours for three days. Leaving the conference, students were better

able to understand their important roles in school and in their

communities, they learned valuable lessons from our Barrow Elders

and they had a level of excitement and confidence in themselves

that we hope they carry with them for their lifetimes.

Student participant Desiree Kaveolook of Kaktovik

writes:

While I participated in the First Annual 2002 Leadership

Conference, I learned many values a person must have to be a

good leader. One of the senior guest speakers, Kenneth Toovak,

said in order to be a leader, we have to get up early in the

morning to plan for the day. That way the people would get more

work done, and they would feel better about themselves. I also

learned that the cultural values are important to an Iñupiaq

leader. They connect us to our ancestors and land. Commitment,

confidence and communication are also important values to have

for being a leader. I think that a leader who does not have commitment

would not be able to hold a community together. I also don’t

think someone could be a leader without confidence. A person

could not be a leader without communication, because he or she

would not know what the people feel or want. This conference

taught us many things. I am looking forward to next year’s

conference and hope that it is as successful as this one.

Day One featured community panels:

- "Qualities of a Good Leader" with Elders

Martha Aiken, Kenneth Toovak and Lloyd Ahvakana.

- "Qualities and Values of Sound Leadership" with

community leaders Jacob Adams, Margaret Opie and Audrey Saganna.

- "Overcoming Obstacles in Leadership" with

Dennis Packer, Bobbi Quintavell and Jaylene Wheeler.

- Students also watched a film "Capturing Spirit:

An Inuit Journey", a film which focuses on how to make positive

choices to live a healthy life.

Day Two featured:

- "Leadership Shadow" experience. One

student was paired with one community leader on the job to learn

and witness the skills needed to be a successful leader on the

North Slope.

- General session meetings to discuss their experiences.

- Students also worked on revisions to the districts

own "Student Rights and Responsibilities" section of

the Student-Parent Handbook.

Day Three featured more community leader panels:

- "How to use Media to Effectuate Change" with

Rachel Edwardson.

- "Making a Difference Through Teaching" with

Innuraq Edwardson.

- "How the Board Makes School Policy" with

Rick Luthi and Susan Hope.

- "How the North Slope Borough Assembly Adopts

Ordinances" with Molly Pederson and Bertha Panigeo.

- "Serving on the NSB Assembly or School Board" with

Mike Aamodt and Tina Wolgemuth.

- The students wrapped up the conference with

an examination of the following issues and developed strategies

for initiating positive change:

- Drugs and alcohol

- Violence and suicide

- Community in school

- Jobs and teaching

"I learned that if you’re trying to become

a leader, don’t give up at what you are doing! Do your best

at it!" —Donald Taleak

For more conference information please contact Cathy

Rexford at: Cathy.Rexford@nsbsd.org.

Athabascan

Region Athabascan

Region

2002 Alaska Indigenous People’s

Academy

by Linda Evans

The week-long Arctic Village Elders Academy, sponsored

by Project AIPA, was held on the East Fork of the Chandalar River

at a traditional campsite that has been used by the Gwich’in

people for thousands of years. The mountains of the Brooks Range

surrounded the camp and the quiet waters of the river flowed by

peacefully. What an awesome learning environment!

Our teachers were Trimble Gilbert, Maggie Roberts,

Florence Newman and Elder-in-training, Kenneth Frank. They were

natural teachers in their traditional environment. Each has so

much traditional knowledge and they were happy to share. The theme

for the camp was caribou. We learned about the caribou and traditional

subsistence living in this area. Some of the topics covered included:

caribou skins, dry meat bags, dog packs, babiche, tools made from

the lower leg of the caribou, games made from the caribou knuckles

and hooves, snowshoe lacing using babiche, building a fish trap

with willows, fishing with a net, cutting and drying whitefish,

sucker, pike, and lush, traditional cooking over the campfire,

some Gwich’in games, setting snares made with babiche, traditional

uses of plants and roots in the area and some traditional stories

told by the Elders. The participants made a list of the learning

activities the group participated in and came up with a total of

fifty-nine different activities in that short period of time. Besides

working on caribou skins, the only other part of the caribou we

worked with was the lower leg, including the hoof. All the tools

and games we made came from that one part of the caribou. It was

amazing how much knowledge the Elders have. Imagine what we could

have done with a whole caribou if our camp lasted two or three

weeks!

During the time we spent at camp learning from the

Elders, some of the traditional values taught were:

- take care of yourself

- use the resources wisely

- don’t be wasteful

- share with others

- work cooperatively with others–teamwork

- humor

Staying at camp and working with the Elders helped

me realize how intelligent our ancestors were to use the natural

resources of the land to survive. Now I am a part of that learning

process and have the responsibility to pass my knowledge on to

our young people.

Part of the process of attending the Elders’ Academy

is to develop curriculum units from the indigenous knowledge learned

from the Elders. I am proud of the teachers and their hard work.

Project AIPA will have eight curriculum units to implement in the

schools by the end of October:

- Living in the Chandalar Countryby Kathleen Meckel

(language arts and social studies unit for level 2, grades 3—5)

- Huslia Plant Project by Gertie Esmailka (integrated

unit on local plants for level 2,grades 3—5)

- Caribouby Twila Strom(integrated unit on caribou

for level 2, grades 3—5)

- We are the Gwich’in by Debra VanDyke (language

arts and social studies unit for level 4, grades 9—12)

- Gwich’in Games by Cora Maguire (language

arts and social studies unit on games for level 3, grades 6—8)

- Subsistence Fishing on the Chandalar by Linda

Evans (integrated unit using a traditional story for level 1,

grades K—2)

The resource materials developed from the camp experience

will include:

- a resource book with pictures of the Arctic Village

Camp by Carol Lee Gho,

- a handbook for setting up a cultural camp by Linda

Green and Virginia Ned,

- a poster showing the uses of caribou and

- a poster showing the seasonal activities in the

Gwich’in area.

I encourage school districts, administrators, school

boards and local schools to get involved in making a camp experience

available for your students and teachers. The experience will enhance

your educational program immensely and make education fun for everyone

involved.

AIPA Culture Camp

by Linda Green

On June 2, 2002 I attended the Project AIPA Culture

Camp in Arctic Village. The seven-day camp was located 45 minutes

by boat from Arctic Village. Nine teachers from the Yukon Flats,

Fairbanks NSBSD and Yukon-Koyukuk and myself arrived at the camp

in three boats. The Elders from Arctic Village were Trimble Gilbert,

Maggie Roberts and Florence Newman. Our camp cook, Margaret Tritt,

soon became part of the Elders teaching teachers. Other camp personnel

included a video cameramen and three camp helpers, which were 14-year-old

boys from Arctic Village.

We arrived on Sunday and began setting up the tents

that would be our homes for the week. As we finished, we got acquainted

with each other. The camp theme was "Caribou". Monday

morning started with breakfast and a gathering led with a prayer

from one of the Elders, followed by a review of the agenda. After

that we took three caribou skins to the lake, about an eighth of

a mile away from the camp, to be soaked for approximately 24 hours

before working on them. As we did this the Elders went over each

part of the caribou. Then we started working with the leggings.

Under the direction of the Elders, we made two different toys and

a tanning tool. As the teachers finished their projects they went

to another area and started cutting white fish that were caught

in the net that day. After dinner we were very tired from working

all day so we all slept very nicely.

Tuesday began with breakfast and a prayer and the

Elders started telling stories about how the Gwich’in people

were totally dependent on the caribou herd. There were always camps

around the herd. There were no nets, so people built fish traps

and used spears made from willows. Bows were made from caribou

skin and arrows were made from the antlers. Flints were used to

make the arrowhead. It wasn’t important to have a clock because

each day was filled with trying to survive. People walked more,

because that was the only mode of transportation. We went over

uses of the caribou skin, stomach and bones. Each use was intertwined

with a traditional value. In the evening the teachers went over

different strategies to use in integrating what we were learning

into school curriculum and standards.

Wednesday we rose and had breakfast and a prayer.

Then we started working on the skins that we had put into the water

on Monday. It was 80 degrees out when we hung the skins on a tree

and started cutting the hair off with sharp knives. Others were

scraping the skins that had the hair already removed. After dinner

we made babiche from previously prepared skin, as well as fish

hooks from the bones. We also playing string games the Elders showed

us.

Thursday we continued fleshing and cutting hair off

of the eight skins we had. That evening we discussed values students

should know–things such as who they are and where they came

from. Each morning should be started with a prayer for strength.

Teachers also talked about the units they would write, how each

would be different from the standard curriculum, the importance

of teaching from a traditional perspective and how this learning

could be brought into the classroom. Units should be started with

a story by an Elder and last a minimum of two weeks. Another idea

was to start a unit explaining the seasons. We ended with Joel

Tritt, second tribal chief of Arctic Village, talking to the group

about learning and how it is important for students to learn about

the old ways in order to survive.

Friday we began to cut the caribou skin for a sack.

Patterns were made and the skin was sewn with sinew from the caribou.

Since some were finished before others, so they went to the fish

cutting table or made more things from the caribou hooves. We also

included a field trip five miles up the river to an ancient caribou

fence. Most of the group went, though some stayed behind and spent

the day making snowshoes with the babiche from the caribou. Upon

their return, the group expressed a deep spiritual experience in

walking around and looking at the remains of the old caribou fence

and the slaughter house. They talked about how clean the environment

was and that very little was disturbed. They also talked about

the way the fence was made so that caribou would go in and because

of the mountain on one side, they would be trapped.

Saturday we finished our projects and started packing

up the camp. We left on Sunday and spent the night in Arctic Village

in order to catch the mail plane to Fairbanks Monday. The teachers

spent two days in Fairbanks writing and working on the units that

they developed in camp, which needed to be completed by July 31

so they could be showcased at the AINE conference that weekend.

I brought eight draft copies of the units made from

the camp to present in a workshop at the Sixth World Indigenous

Peoples Conference on Education that was held near Calgary, Alberta,

Canada on the Nakoda Nation Reserve from August 3—10. I also

displayed videos made from the culture camps, along with camp booklets

with lots of digital photos. Florence Newman, an Elder at the Arctic

Village camp, also attended the conference. Her presentation, along

with the booklets and videos, gave the workshop participants a

strong, positive feeling about the culture camps sponsored by the

Alaska Indigenous Peoples Academy and the Association of Interior

Native Educators. Further information and curriculum resources

are available on the AINE and ANKN web sites.

Fall Course Offerings for Educators

in Rural Alaska

by Ray Barnhardt

Just as the new school year brings new learning opportunities

to students, it also bring new learning opportunities for teachers

and those seeking to become teachers. This fall rural teachers

and aspiring teachers will have a variety of distance education

courses to choose from as they seek ways to upgrade their skills,

renew their teaching license, pursue graduate studies or meet the

state’s Alaska Studies and Multicultural Education requirements.

All Alaskan teachers holding a provisional teaching

license are required to complete a three-credit course in Alaska

Studies and a three-credit course in Multicultural Education within

the first two years of teaching to qualify for a standard Type

A certificate. Following is a list of some of the courses available

through the Center for Distance Education that may be of interest

to rural educators.

Alaska Studies: ANTH 242, Native Cultures of Alaska;

GEOG 302, Geography of Alaska; HIST 115, Alaska, Land and Its People;

HIST 461, History of Alaska.

Multicultural Education: CCS/ED 610, Education and

Cultural Processes; CCS/ED 611, Culture, Cognition and Knowledge

Acquisition; ED 616, Education and Socio-Economic Change; ED 631,

Small School Curriculum Design; ED 660, Educational Administration

in Cultural Perspective.

Cross-Cultural Studies: CCS 601, Documenting Indigenous

Knowledge Systems; CCS 608, Indigenous Knowledge Systems.

Enrollment in the above courses may be arranged through

the nearest UAF rural campus or by contacting the Center for Distance

Education at 474-5353 or distance@uaf.edu or by going to the CDE

web site at http://www.dist-ed.uaf.edu. Those rural residents who

are interested in pursuing a program to earn a teaching credential

or a B.A. should contact the rural education faculty member at

the nearest rural campus, or the Rural Educator Preparation Partnership

office at 474-5589. Teacher education programs and courses are

available for students with or without a baccalaureate degree.

Anyone interested in pursuing a graduate degree by distance education

should contact the Center for Cross-Cultural Studies at 474-1902

or ffrjb@uaf.edu.

Welcome to the 2002—2003 school year!

Alaska RSI Contacts

Co-Directors

Ray Barnhardt

University of Alaska Fairbanks

ANKN/ARSI

PO Box 756730

Fairbanks, AK 99775-6730

(907) 474-1902 phone

(907) 474-5208 fax

email: ffrjb@uaf.edu

Oscar Kawagley

University of Alaska Fairbanks

ANKN/ARSI

PO Box 756730

Fairbanks, AK 99775-6730

(907) 474-5403 phone

(907) 474-5208 fax

email: rfok@uaf.edu

Frank W. Hill

Alaska Federation of Natives

1577 C Street, Suite 300

Anchorage, AK 99501

(907) 263-9876 phone

(907) 263-9869 fax

email: fnfwh@uad.edu |

Regional Coordinators

Alutiiq/Unangax Region

Olga Pestrikoff, Moses Dirks &

Teri Schneider

Kodiak Island Borough School District

722 Mill Bay Road

Kodiak, Alaska 99615

907-486-9276

E-mail: tschneider@kodiak.k12.ak.us

Athabascan Region

pending at Tanana Chiefs Conference

Iñupiaq Region

pending at Kawerak

Southeast Region

Andy Hope

8128 Pinewood Drive

Juneau, Alaska 99801

907-790-4406

E-mail: andy@ankn.uaf.edu

Yup’ik Region

John Angaiak

AVCP

PO Box 219

Bethel, AK 99559

E-mail: john_angaiak@avcp.org

907-543 7423

907-543-2776 fax |

Lead Teachers

Southeast

Angela Lunda

lundag@gci.net

Alutiiq/Unangax

Teri Schneider/Olga Pestrikoff/Moses Dirks

tschneider@kodiak.k12.ak.us

Yup'ik/Cup'ik

Esther Ilutsik

fneai@uaf.edu

Iñupiaq

Bernadette Yaayuk Alvanna-Stimpfle

yalvanna@netscape.net

Interior/Athabascan

Linda Green

linda@ankn.uaf.edu |

is a publication of the Alaska Rural Systemic

Initiative, funded by the National Science Foundation Division

of Educational Systemic Reform in agreement with the Alaska

Federation of Natives and the University of Alaska.

This material is based upon work supported

by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0086194.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations

expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and

do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science

Foundation.

We welcome your comments and suggestions and encourage

you to submit them to:

The Alaska Native Knowledge Network

Old University Park School, Room 158

University of Alaska Fairbanks

P.O. Box 756730

Fairbanks, AK 99775-6730

(907) 474-1902 phone

(907) 474-1957 fax

Newsletter Editor

Layout & Design: Paula

Elmes

Up

to the contents Up

to the contents

|