SUBSISTENCE AND ECONOMIC

PLANNING

SUBSISTENCE AND ECONOMIC

PLANNING

"Subsistence is not only a cultural activity, the foundation of several of the Native groups in Alaska, without which their cultures would die. It is also the necessary economic base for their very existence."1

Owen Ivan, Bethel, 1973

Historical Perspective

When economic planners set about to tackle the problems of "poverty" in rural Alaska they usually seem unaware of the role that subsistence plays in the rural economy. With good intentions to relieve the poor of their problems, they often lose track of the fact that poverty has only recently been introduced to Native communities. Up until a hundred years ago people were living in a finely balanced economic relationship with the land.

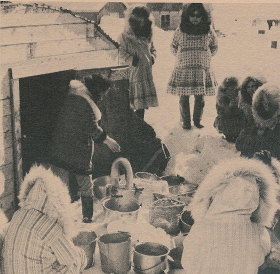

For thousands of years people subsisted from the land and ocean along the west coast of Alaska. In many ways it was a hard life, but it had none of the frustrations and stigmas of poverty, for the people were not poor. Living from the land sustained life and evolved the Yupik culture, a culture in which wealth was the common wealth of the people as provided by the earth. Whether food was plentiful or scarce, it was shared among the people. This sharing created a bond between people that helped insure survival.

The Yupik language has words for being a poor hunter, for being hungry, sick or cold. But there were no words for being rich or poor in the modern sense. These concepts were introduced when white men first came to the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta in the 1830's and 1840's. With the first Russian traders came the idea of wealth and poverty.

These new people added to the process of living the purpose of accumulating. Whether one was accumulating furs, money, land or the souls of converts, lines were drawn between people on the basis of what they had accumulated. Those with more were wealthy, and those with less were poor. The wealthy were better off, and the poor had a problem. These new relationships were reinforced by the new economic system which began replacing food and furs with cash, cooperation with competition, sharing with accumulating either without regard or at the expense of others. The new system had new rules. Accumulating money, "owning" land and other property and knowing how to drive a good bargain were all important in the new system. Native people had to begin learning new ways.

The introduction of new values and concepts in our region has followed the pattern that spread wherever Europeans settled in North America. Searching for the roots of this process of change, D'Arcy McNickle, of the Flathead Tribe of the Pacific Northwest wrote in an article titled, Indian and European that:

"The men who came out of Europe into what they pleased to call the New World were men with a mission. Their mission might be secondary to their immediate needs of security, but it was never wholly absent and at times it was of dominating interest in the actions of individual settlers. The nature of the mission was variously phrased, but essentially it amounted to an unremitting effort to make Europeans out of the New World inhabitants, in social practices and in value concepts."

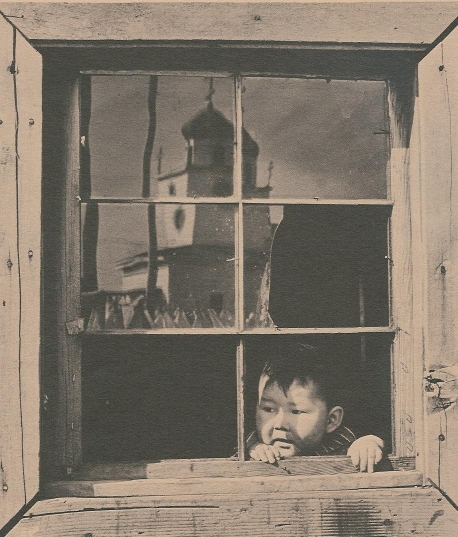

This impact came later to Alaska than elsewhere in North America. In fact, of all the regions within Alaaka the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta is the last to experience the impact of Western civilization. Even though village people in our region remain close to their original way of life, the forces of change are coming rapidly. And they can be devastating.

It is well known how the coming of white men brought diseases like measles and syphilis which killed thousands of our people and physically crippled many more for the rest of their lives. It is not so well known that the economic impact of Western civilization was every bit as devastating to the well being and spirit of the people as the physical illnesses were to their health. Perhaps it is more difficult to see the effects of the Western economic system because the causes are not infections like measles, but are the fundamental and often subtle differences between the Yupik and Western mind and ways of doing things.

"Poverty has only recently been introduced to Native communities."

These differences, these new ways and systems of doing things can be as disturbing to the life of a person or of a culture as the measles infection is to the life of a body. Fortunately a cure has been found for measles. A cure has not been found for our "poverty." Perhaps the difficulty is in how to approach the problem. The cure for measles involves a vaccination in which a little bit of the infection is introduced so the body can develop the strength to cope with it. For poverty, all the attempted cures have involved ever increased doses of the Western way of life in the hope that the new system will somehow successfully replace the old one. Instead of trying to replace the Yupik way of life, efforts should be directed toward joining the two cultures in meaningful ways.

During this time of great change we are in fact living a combination of two cultures, but at present it is a haphazard and not very satisfactory mixing of two ways of life. Economically, as well as in other ways, we are in an interim period in which, for want of a cure or solution for our "poverty", we are supported by welfare and food stamp programs. We are more or less kept alive while our "problems" are being studied.

"The Yupik language has no words for being rich or poor.

To begin looking for solutions we have to look at the process of change we are caught up in. We have to ask, Where are we? How did we get here?

It may be useful to look at how economist George Rogers has summarized the relationship between Alaska development and the Native Alaskan. He writes:

"Following the first contacts with Western civilization, most of the Native Alaskans were simply by-passed by the course of economic developmentÉ. In the process their aboriginal society and culture were destroyed and their numbers drastically cut down. During the American period the coastal Eskimos suffered death from starvation and strange diseases brought in by the whalers who virtually extinguished the walrus and whale resources upon which the Eskimos depended for survival. The Southwest Indians managed to keep the white invaders at arm's length because of their savage and warlike reputation, but their downfall came near the end of the nineteenth century when commercial fishermen and cannery men from California and the Northwest Coast invaded and overtook their fisheries. The turn of the Arctic and Interior Eskimo and Interior Indians came when Alaska shifted from its colonial to its military period. Finally all were embraced by the coming of the welfare state to Alaska in the 1930's when national programs designed to meet the needs of a twentieth century urban industrial society were uniformly applied to a people still far from that condition.

"The results of these contacts between Native Alaska and the mainstream of Alaska's economic development did bring some benefits and opportunities for participation, but on the whole the story was a contradictory one of unconscious or conscious cruelty and unavoidable or needless human misery. During the Colonial period the Natives were treated as part of the environment in which the exploitation was undertaken. If they could be turned to a use in serving the purpose of getting the resource out as easily and cheaply as possible, they might be enslaved as with the Aleuts, or recruited, as were the Southeast Indian fishermen and their women as a local workforce in the harvest and processing of marine resources. If not, they were ruthlessly pushed aside while their traditional resources were exploited to the point of extinction by seasonally imported work forces as was the case with the coastal Eskimo.

"The impact was, on the whole, destructive to traditional ways and to the Native people themselves, and their economic participation was marginal at best. Whether they participated or not, their very survival required adaptation of their traditional ways to the new conditions imposed by the altered environment."7

"Like strapping bandages on a dying person

Bristol Bay is a good example of this process at work. Originally people subsisted from the land and sea; the tremendous salmon runs provided a reliable source of food. Commercial fishing began with an attitude of get what you can. It was only a matter of time before urban politicians and outside economic interests permitted the salmon runs to be exploited nearly to extinction.

The local people, Native and non-Native alike, were left impoverished. Then the government became concerned. Then fishery research was called for. Limited entry demanded. Then food stamps were passed out to people who used to fish.

Somehow or other Native people were expected to adapt their traditional ways to this Western economic system.

On the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta the changes people have undergone might be considered adaptation. And they have more or less survived. There are nearly 13,000 Native people living in the region, about half the number estimated to have lived here before the coming of white people. Life expectancy is a little more than half that of people living in the lower 48. The day to day health of people and the medical care they receive are among the poorest in the nation. The rate of alcoholism is one of the highest in the country. The average cash income of our people is less than $4,000 per family. But our region has one of the highest birth rates in the United States. Most of our children can speak their Native language, and the land can still provide us with most of our basic needs. The question at this time is: How do we move from survival to well-being?

Economic Evaluation of Subsistence Resources

Economic planners must begin looking at the economic values of subsistence living. This is not easily done. Since subsistence is an entire process of living it can not be readily assessed and analyzed by Western methods of cost-benefit and supply and demand analysis.

Dollar values can not be placed on subsistence resources as they can on board feet of timber or barrels of oil because the use of subsistence resources involves many things which can not be translated into cash.

However, if the people on the Delta did not obtain food from the land and waters, they would have to buy it somewhere. This would cost money which would have to come from somewhere. The amount of cash needed to replace subsistence foods has to be considered.

This problem of replacing subsistence foods with store bought food is not unique to our region. Speaking to the problems that a conversion to store food would create on a statewide basis, Roger Lang, President of the Alaska Federation of Natives, has said:

"If we buy the fact that subsistence living is an economic reality along with the traditional, cultural and social use of it, then we must treat it that way. Should you remove it, it's tantamount to removing banks from Anchorage, Safeway stores from Fairbanks. That's the simple fact.

"When you talk about that type of removal, when you talk about the significance of the dollar to replace it, I don't find those dollars anywhere in Alaska or the Federal government or in the region or village corporations. There is no immediate substitute to the consequence of removing subsistence living in any degree. There's not enough dollars."2

On the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta there are not enough dollars to replace even

a small portion of the subsistence food upon which the people rely. With

most village families obtaining over 75 per

cent of their food from the land combined with the average annual cash

incomes which are among the lowest in the United States, subsistence is

an economic necessity. Emphasizing this imperative to the Land Use

Planning Commission, Yupiktak Bista's Director, Harold Napoleon has said:

"The presumption that at this time Native people do not have to subsist is inaccurate. I think they still have to subsist, especially in our area they have to subsist. A young man told me last night that he cannot go a day without eating fish. Now that's true. And this is true of every village. I'm not sure that you'll find one village or one family in that whole area that can go without subsistence hunting. And there is not an economic base right now to support a cash economy type of life. There isn't." I think the average family income on the Delta is something like $3714. You try to live on $3714 and see how far it goes. You have to buy clothing. You have to buy food. You have to keep your house warm. Whatever money they do get is going to be spent on gasoline to do this subsistence hunting. It's going to be spent on stove oil to keep their house warm. It's going to be spent on clothes so their kids can go to school. So, there is going to have to be a great increase in cash in the villages if we're going to expect them to go on the cash economy. Especially in the villages where everything costs nearly two times as much as it does out here. The villager needs twice as much money as the city person to live on the cash economy."2

"The 'worth' of a moose or caribou, or of a fish or duck taken for personal consumption, is a value not currently defined in the market place as it is illegal to sell these commodities. However, this food is still obviously 'worth' a great deal, for if it were not available, the person would have to buy the equivalent in a store. An attempt has to be made to evaluate the gross dollar value of these products in terms of both Anchorage and Bethel service center prices for equivalent items."4

Probably the greatest difficulty in assigning dollar costs to the subsistence food used by a family, village or the entire region is the lack of statistics defining just what quantities of each subsistence food is used. A hunter knows about how much food he needs to get for his family, but he doesn't keep track of how much his neighbor gets, or the whole village, or the other villages in the region. Subsistence resource planning is greatly handicapped by the negligence of the State and Federal government in determining precisely who uses how much of which subsistence foods.

"The question at this time is: How do we move from survival to well-being?"

The limited statistical data available includes the following information which may be useful in setting the rough parameters of the quantities of subsistence foods harvested each year.

Percentage of Dependency on Subsistence |

Number of

Families Akiakchak |

Number of

Families

Mountain Village |

| 100% | 10 |

9 |

|

76 - 99% |

1 |

3 |

| 51 - 75% | 2 |

2 |

| 26 - 50% | 0 |

2 |

|

1 - 25% |

0 |

3 |

|

0% |

4 |

2 |

| Total | 17 |

21 |

Although this information is useful in getting a picture of the quantities of certain species taken it doesn't construct a picture of the per capita, village or regional dollar value of the subsistence foods. To try to obtain at least a rough breakdown of this perspective, several villages cooperated with the Fish and Wildlife Service in 1973 to conduct a village subsistence survey. The village of Tuluksak, along with several others, provided a species breakdown as shown in the accompanying table. To summarize the dollar costs of replacing subsistence foods we find the annual per capita cost at Bethel replacement prices to be:

| 1973 | 1975 (40% increase) | |

| Tuluksak | 2,146 |

$3,004 |

| Kasigluk |

1,800 |

$2,520 |

|

Russian Mission |

1,893 |

$2,050 |

| Emmonak |

656 |

$ 918 |

TULUKSAK

| Species/Food Item | Harvest2 |

(Pounds)

Average

Utilizable

Weight

|

Average

Current $ Value of Skin |

$

Value per Animal

|

Total $ Value |

||||

Anchorage |

Bethel |

Anchorage |

Bethel |

Anchorage |

Bethel |

||||

|

Big

Game |

|||||||||

|

10 |

700 |

$1.35 |

$1.85 |

Not Determined |

$945.00 |

$1295.00 |

$9,450.00 |

$12,950.00 |

Black Bear |

5 |

150 |

1.35 |

1.85 |

Not Determined |

202.50 |

277.50 |

1,013.00 |

1,388.00 |

Brown Bear |

1 |

225 |

1.35 |

1.85 |

Not Determined |

303.75 |

416.25 |

304.00 |

416.00 |

Total Lbs.—Big Game |

7975 lbs. |

||||||||

| Furbearers | |||||||||

Beaver |

500 |

20 |

.69 |

1.25 |

32.00 |

45.80 |

57.00 |

22,900.00 |

28,500.00 |

Muskrat |

2000 |

2 |

.69 |

1.25 |

1.25 |

2.63 |

3.75 |

5,260.00 |

7,500.00 |

Mink |

65 |

40.00 |

40.00 |

40.00 |

2,600.00 |

2,600.00 |

|||

|

30 |

43.00 |

45.00 |

45.00 |

1,350.00 |

1,350.00 |

|||

|

10 |

45.00 |

45.00 |

45.00 |

450.00 |

450.00 |

|||

Lynx |

65 |

80.00 |

80.00 |

80.00 |

5,200.00 |

5,200.00 |

|||

Marten |

1 |

25.00 |

25.00 |

25.00 |

25.00 |

25.00 |

|||

Weasel |

30 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

30.00 |

30.00 |

|||

|

5 |

.5 |

.69 |

1.25 |

.65 |

1.10 |

1.28 |

6.00 |

6.00 |

Hare |

165 |

3 |

.69 |

1.25 |

- |

2.07 |

3.75 |

342.00 |

619.00 |

Wolverine |

3 |

70.00 |

70.00 |

70.00 |

210.00 |

210.00 |

|||

Wolf |

5 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

500.00 |

500.00 |

|||

Total Lbs. - Furbearers |

14498 lbs. |

||||||||

Porcupine

|

3 |

10 |

.69 |

1.25 |

Not Determined | 6.90 |

12.50 |

21.00 |

38.00 |

|

30 lbs. |

||||||||

Waterfowl & Birds

|

|||||||||

Ducks |

1150 |

1 |

$.69 |

$1.25 |

Not Determined |

$.69 |

$1.25 |

$794.00 |

$1,438.00 |

Geese |

990 |

3 |

.69 |

1.25 |

Not Determined |

2.07 |

3.75 |

2,049.00 |

3,713.00 |

Swans |

165 |

10 |

.69 |

1.25 |

Not Determined |

6.90 |

12.50 |

1,139.00 |

2,063.00 |

Cranes |

5 |

4 |

.69 |

1.25 |

Not Determined |

2.76 |

5.00 |

14.00 |

25.00 |

Loons |

10 |

2 |

.69 |

1.25 |

Not Determined |

1.38 |

2.50 |

14.00 |

25.00 |

Ptarmigan |

3000 |

1 |

.69 |

1.25 |

Not Determined |

.69 |

1.25 |

2,070.00 |

3,150.00 |

Grouse |

20 |

1 |

.69 |

1.25 |

Not Determined |

.69 |

1.25 |

14.00 |

25.00 |

Total Lbs. — Waterfowl & Birds |

8830 lbs. |

||||||||

| Fish | |||||||||

Whitefish |

16550 |

1.5 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

- |

1.50 |

1.50 |

24,750.00 |

24,750.00 |

Pike |

6600 |

6 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

- |

6.00 |

6.00 |

39,600.00 |

39,600.00 |

Lush |

30000 |

4 |

.69 |

1.00 |

- |

2.76 |

4.00 |

82,800.00 |

120,000.00 |

Shecfish |

660 |

9 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

- |

9.00 |

9.00 |

5,940.00 |

5,940.00 |

Blackfish |

200 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

- |

200.00 |

200.00 |

|||

Smelt |

3300 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

- |

3,300.00 |

3,300.00 |

|||

Grayling |

300 |

1 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

- |

1.00 |

1.00 |

300.00 |

300.00 |

Rainbow Trout |

165 |

2 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

- |

2.00 |

2.00 |

330.00 |

330.00 |

King Salmon |

1400 |

15 |

1.43 |

2.50 |

- |

21.45 |

37.50 |

30,030.00 |

52,500.00 |

Other Salmon |

7000 |

4.3 |

1.09 |

1.654 |

- |

4.69 |

7.09 |

32,830.00 |

49,630.00 |

Total Lbs. - Fish |

245520 lbs. |

||||||||

| Berries | 5000 lbs. |

.87 |

1.304 |

4,350.00 |

6,500.00 |

||||

| Rosehips | 50 lbs. |

.49 |

.744 |

25.00 |

37.00 |

||||

| Rhubarb | 3000 lbs. |

$.39 |

$.594 |

$1,170.00 |

$1,770.00 |

||||

Total Lbs. and Dollars |

284903 lbs. |

$281,380.00 |

$377,678.00 |

||||||

Lbs. and Dollars per Capita |

1619 lbs. |

$1,599.00 |

$2,146.00 |

||||||

These values of subsistence foods to the region are generally supported by the first phase of a Nunam Kitlutsisti study to document subsistence use in all villages within the region. In this study a subsistence calendar was distributed to the head of virtually every household within the region. Day by day, the amounts and types of subsistence foods harvested were recorded and returned to Nunam Kitlutsisti. Dollar values were not calculated at the higher cost of commercial replacement foods but at the values these foods were known to have sold for within the region. For the months of January and February, which may be the lowest subsistence harvest months of the year, the following results were obtained.

"Virtually all subsistence foods have a high nutritional value, whereas many commercial foods may be tasty but are low in nutrition."

More Than Cash

First, inflation affects commercial foods which must be purchased with cash. Each year the cost of commercial foods will rise and the amount of effort a village person will have to expend to obtain the needed cash is likely to increase.

Second, the importation of food into a rural area is subject to a variety of factors which can affect the availability and cost of commercial foods. Both shortages of 2 certain food products on the general market and regional transportation problems can cause high prices and unavailability of commercial food items.

Third, the quality of a subsistence diet is probably a great deal higher than the average diet of commercial food for people who have barely enough money to buy food from a store. Although there has not yet been a thorough study of the relative nutritional values of commercial and subsistence foods, there are apparently a number of nutritional advantages to subsistence foods. In a sense, all subsistence foods are "organically" produced; they contain none of the pesticides and chemical additives that most commercial foods contain. Also, virtually all subsistence foods have a high nutritional value, whereas many commercial foods may be tasty but are low in nutrition and some, such as sugar and soda pop, may have an overall harmful effect.

Fourth, fresh food that is not subsistence food can be very hard, if not impossible, to get, no matter what the cost. Village stores carry very little, if any fresh food, and even Bethel does not have a good selection of fresh food. Of course, people with freezers can store some fresh food— both subsistence and non-subsistence. But it is almost impossible to keep fresh produce for any length of time, even if one can pay the high cost of having it flown in. In winter even flying it in presents problems, because it often freezes and spoils during the transportation process.

"The economic value of subsistence food when there are no fresh-food alternatives is so high it cannot be quantified. In this economic sense, subsistence food cannot be replaced with dollars."8

"It is important that the equating of dollar cost or dollar equivalent not be interpreted as representing equal value. For example, suppose that a pound of meat at the store costs the purchaser $2.00; then the dollar cost of moose would also be $2.00 per pound of meat. However, the value is the same only if the satisfaction from consuming the pound of store meat is the same as the satisfaction derived from consuming a pound of moose meat. If the moose meat is preferred over store meat, then the substitute value is underestimated by using only the dollar equivalent."8

For many people in our region there simply are no substitutes or replacements for the fish, seal, birds and other subsistence foods. Margaret Nick Cooke is an example of a person who still needs subsistence foods even though she is away from her village and could afford to buy from the store. She has testified that she is opposed to any legislation,

"...that would tell me and many others that we can no longer have seal meat and seal oil which I have been eating since I was my baby's age.. . Our immediate area does not have seals that is why we buy seal meat and seal oil from the coast. And believe me, my body must have seal oil. I eat it almost daily. It is necessary for us like you people have to have salad oil in your salad... I have never been in jail or arrested in my life, but if this bill passes in its present form—I will become a criminal. My body is used to seal oil and must have seal oil, I will continue to buy seal oil no matter what."5

Or as Guy Mann of Hooper Bay described his use of seal oil:

"We Eskimos use seal oil like this. In spring we hunt seals. Then skin dry up. When dry we put oil in seal skins. Then save it for winter. Then after season we fishing. The fish dry. Then smoked. After smoked we put dry fish into the seal skin with seal oil and we save it for winter. And all summer we not seal hunt. And in September we start seal hunt again. Then we seal hunt all winter because we Eskimo like to eat all kind of oil from ocean. Every time when we eat we take a seal oil. Please, please help us. We need help. We don't want to stop seal hunt. And when we eat something without seal oil, our stomachs kind of sick."5

So it is that subsistence continues to be both economically necessary and culturally valuable. This implies that economic development projects that propose to create new jobs, more village cash flow or great regional wealth should be planned and coordinated with the existing subsistence economy and lifestyle of the people. The following are ways in which coordination between the subsistence economy and the cash economy can be approached.

"Agencies and private enterprises in the region should try to arrange their work programs to allow people to take a leave of absence when they have to hunt and fish at certain times of the year."

Energy Use

"We need the assistance of others in the matter of

energy, particularly in developing an independent research program that

concentrates on the problems of rural Alaska."

"We need the assistance of others in the matter of

energy, particularly in developing an independent research program that

concentrates on the problems of rural Alaska."Behind David Friday's call for assistance lies a problem that could by itself jeopardize subsistence and any other way of living in the villages. Energy problems that may cause inconvenience elsewhere in the United States can cause severe hardships in the rural areas of Alaska.

Energy problems have already been experienced in our region, as David Friday summarized for the Federal Energy Administration.

"In our region, the fifty-seven member villages have doubled their oil and gasoline consumption since 1969. Our people in the past normally relied on wood, peat, and local coal deposits for heating their sub-surface dwellings. Framed houses, poor insulation, large public buildings, and the internal combustion engine have turned our traditional subsistence villages dependent on local heating sources toward heating and electricity generated from oil.

" When the highly publicized oil shortage occurred in the nation, our villages had already lived with the situation. In 1973, 26 of our villages ran out of oil and gasoline before summer re-supply. In 1974, 34 villages suffered some form of rationing or complete exhaustion of their oils."

To begin minimizing the impact of energy use problems in the villages the following considerations are recommended:

"As energy prices rise, where will people get the extra money that will be needed? Will they be forced to leave the villages to look for better employment opportunities?"

The development of energy resources within the region could cause some extremely serious problems for subsistence resources. Development of oil and gas on the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta can be expected from three directions:

Severe impact on subsistence resources could easily come from each of these sources and taken together their combined impact could be disasterous. The most serious impact on the subsistence of life-style will result from:

To protect subsistence values several considerations must be made by the State and Federal governments and Calista:

Welfare

Or can various forms of public assistance be a complimentary part of the subsistence way of living?

Such questions arise as various public assistance programs are used more extensively in our region. In recent years, three types of income assistance programs have been available to people in the villages: BIA welfare payments; food stamps; and State welfare payments which include Aid to the Blind, Old Age Assistance, Aid to the Disabled, and Aid to Dependent Children.

The extent to which these programs have been utilized has been summarized in a Department of Interior impact statement.

Judging from recent statistics (available only for the month of October 1972) about 35 percent of the households on the Delta currently receive welfare payments from the State of Alaska. The number of households receiving B.I.A. welfare payments ranged from 20 to 40 percent in recent years. Food stamp records, kept by month, show that an average of about 42 percent of the population was receiving food stamps in 1971, and about 31 percent in 1972. The extent to which these three types of income assistance each serves the same group is unknown. Average annual household income from State welfare payments, judging from October 1972, is about $2,500. Average annual income from food stamps in 1972 was about $1,800 per household, $324 per capita.

The degree to which these programs are used reflects the extent of poverty conditions in the villages. And they illustrate how such assistance has become an important part of the basic livelihood of many families.

However, the flow of public assistance funds into villages does not begin to replace the need to use subsistence resources. It must be kept in mind that welfare payments in the villages buy only about two-thirds of what they would buy in Anchorage and other places where prices are substantially lower. Even if public assistance were doubled or tripled it would not meet all the basic needs now being met with subsistence activities, let alone replace the cultural values of subsistence living.

The funds from the various assistance programs are in most instances meeting real and acute needs. Without them, many people would be in distress—unable to survive solely from subsistence hunting and fishing and finding no opportunities for employment in the region.

Without exploring all the pros and cons of the various assistance programs, the following considerations might be helpful in coordinating these programs with the general subsistence patterns of this region.

Return to Does One Way of Life Have to Die So Another Can Live?