This collection of student work is from Frank Keim's classes. He wants to share these works for others to use as an example of culturally-based curriculum and documentation. These documents have been OCR-scanned and are available for educational use only.

This collection of student work is from Frank Keim's classes. He wants to share these works for others to use as an example of culturally-based curriculum and documentation. These documents have been OCR-scanned and are available for educational use only.Special | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O

P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | ALL

Ravens: Not Easy To Catch - More About Raven:Ravens: Not Easy To

Catch

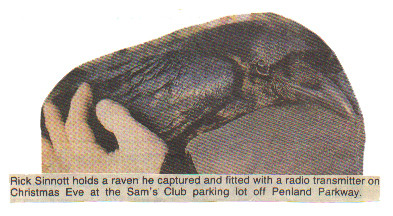

Rick Sinnott slides open the van side door, squats on the floor and lifts the cannon into position. "This is like a drive-by shooting," he says under his breath. Suddenly, there's a blast that sounds like a rifle shot. Four steel cylinders fly outward from the cannon. The cylinders are attached to a 12-foot net, which lands about 25 feet from the van. The target flies to the nearest tree. "Dang it!" Sinnott shouts as he jumps out of the van to collect the net. "Five feet closer we could have gotten it." It's not easy catching a bird as wily as the raven. Sinnott works all day trying to capture ravens. He's been at it more than a month and has grabbed 39 so far. He wants 60 total. When he catches them, he tags them and straps tiny radio transmitters on their backs. Sinnott, a wildlife biologist with the state Department of Fish and Game, is spending $39,000 of U.S. Defense Department money to study the habits of Fort Richardson's ravens. Scientists rarely get funds to study an animal like ravens that aren't endangered or hunted, Sinnott says. So when the Pentagon gave Fort Richardson $69,000 to conduct a board survey of the animal and plant population on post, he urged military officials to spend part of that money on ravens. For years, he's been curious about ravens, which are popular with the public but an enigma to scientists. To his surprise, the military agreed. "We've counted every darn moose on base," says Bill Gossweiler, chief of the natural resources branch at Fort Richardson. "But we don't know much about ravens, other than we have quite a few of them." Sinnott says scientists don't even know the basics about ravens, such as, Where exactly do they sleep at night? Where do they nest? How many are there in the city? Where do they go in the summer? Before you track ravens, though, you've got to catch them. This is no easy task when it comes to ravens, the brains of the bird world. First, Sinnott tried building a huge chicken-wire trap, 25 by 30 feet wide and 7 feet tall. He baited the trap with moose meat for 10 days to get the ravens used to it. Although they weren't flying into the trap, he continued with the scheme. Coached by a visiting raven expert from Maine, Sinnott tied a wire to the metal pole that propped open the trap door. He then waited behind a snowbank 300 feet away. Sinnott hoped to pull his end of the wire and capture maybe 30 ravens at one time. He and the raven expert waited two days, but unlike the ravens in rural Maine, which were easily fooled by this kind of trap, the Anchorage ravens wouldn't go in. One time, when two ravens flew into the trap, Sinnott pulled the wire, but the pole had frozen to the ground and wouldn't budge. By the time Sinnott got the door to close, the ravens had escaped. Sinnott figures that Anchorage ravens are better fed than their Maine cousins and don't take any unnecessary risks. Next, Sinnott tried leg traps, the kind used for small mammals except with edges covered in rubber so they wouldn't break the ravens' legs. He baited the traps with an orange, cheese-flavored food product that ravens find irresistible Cheetos. However, these traps need to be covered with snow, and ravens like hanging out in places without much snow, like parking lots. When Sinnott placed a trap in a parking lot and covered it with snow, the ravens wouldn't touch the bait. Sinnott then threw some Cheetos on the pavement near the parking lot edge, and also sprinkled a few on a snowbank where he had buried the trap. That worked a few times, but the ravens quickly learned to avoid Cheetos near snowbanks. "They know those Cheetos are bad news," he says. "They'll watch them for hours. When they get real suspicious, they all leave the area as soon as I throw Cheetos on the ground." Sinnott also uses peanuts, dog food and french fries for bait. But mindful of the ravens' logical abilities, he tries not to do anything unusual. For example, he won't put Cheetos in front of a McDonald's or french fries in a church parking lot. "It's a real personal thing between them and me," he says. "It's the way they look at me. I can sometimes see the wheels tuming inside their heads. They look at the pile of snow and then look at me, and they're thinking, 'now I don't want to eat those Cheetos right now.' " "Sometimes I get a bigger kick watching them avoid being caught than actually catching them." Sinnott has caught most of the ravens with a net cannon. He shoots from a van because ravens are less afraid of vehicles than people. The transient ravens probably don't stick to Fort Richardson's 60,000 acres, and neither does Sinnott. When he gave up on the idea of catching a whole flock of ravens at one time at Fort Richardson, he decided to nab ravens from all over town. He's caught ravens in the parking areas of the Anchorage International Airport, the Northway Mall and Carrs Huffman. When he's raven hunting, Sinnott wears sound-deadening ear muffs to protect his hearing from the cannon, and thick gloves to protect his fingers from the ravens. When he catches a raven, he and his assistant quickly retrieve the net so none of the other ravens sees it. "The thing is," Sinnott says, "every time you mess with one of these guys, that's just that many more ravens who know what you're up to." Sinnott estimates as many as 2,000 ravens fly to Anchorage every winter to feed on our refuse. He thinks they may summer around Prince William Sound, the Mat-Su valleys, and the Kenai Peninsula. Their long, narrow wings, characteristic of migrating birds, allow them to travel long distances in their search for animal carcasses, their usual food in the wilderness. "They're commuters," Sinnott says. "But where is their bedroom community?" After he catches a raven, he wraps tape around its beak and legs. Then he slips it into a harness that carries a radio transmitter weighing less than an ounce. Finally he pop-rivets a plastic, numbered tag onto the skin of its wing. The whole process takes about 30 minutes. The transmitter will emit a signal for two years. Sinnott plans to fly in an airplane to track the birds. By the end of this winter, he figures he'll know where the ravens sleep at night. Perhaps. But not if the ravens figure out what he's up to first.  | |

|