Alaska Native in Traditional Times: A Cultural Profile

Project

as of July 2011

Do not quote or copy without permission from Mike

Gaffney or from Ray Barnhardt at

the Alaska Native Knowledge Network, University of Alaska-Fairbanks. For

an overview of the purpose and design of the Cultural Profile Project, see Instructional

Notes for Teachers.

Mike Gaffney

Chapter Five

The Six Parts of Culture

The broad scientific field of anthropology is built on the concept of culture. It figures in

almost everything anthropologists and ethnohistorians do, whether studying ancient human

remains or a society’s social organization or a people’s folklore and oral traditions. Even

political scientists talk about a “civic culture.” This is why we have said that the concept of

culture is has become quite elastic. Indeed, there are almost as many definitions of culture as

there are books on anthropology and ethnohistory. Why? Because each has its own purpose

which requires defining culture in a specific way. Certainly the concept of culture is central to

our work here. To fit our purposes here, we define culture as a distinct way of life and way of

thinking about life that is closely share by a socially organized group of people over an extended

period of time. The remainder of your Cultural Profile Project deals with traditional use and

occupancy of land, social organization, worldview, and cultural products – the very essence of

Native life in those days. So before proceeding, we take a timeout here to break this definition

down into its six essential parts.

Part 1 – Culture is distinctive. Something about a group’s culture — their way of life

and how they think about that life — distinguishes them from other groups. Their cultural

identity is directly tied to their feeling that “unlike other people known to us, we believe and

practice these things.” In turn, other groups acknowledge such differences from their own

cultural perspectives. It can be argued that the word “culture” would not exist if all people

everywhere looked the same, spoke the same language, organized their societies the same way,

and shared the same values, and traditions.

Part 2 – Culture is shared. A distinct

way of life and way of thinking about life, is closely shared by members of

the group. The cultural rules, core values, and cherished traditions

are learned at an early age and understood by all members. This learned cultural

knowledge provides a mental road map for navigating through everyday life.

It is a road map we carry in the

back of our heads. We do not consciously think about these cultural rules,

values, and traditions as we go about our daily lives. We simply do our

culture, mostly without giving it a second thought.1

Anton Chekhov, the great Russian playwright, once observed that “Any idiot can face a

crisis. It is this day-to-day living that wears you out.” Chekhov was talking about daily life

within his own cultural setting. But what about living and working in very different cultural

surroundings where we start out with few clues on how to appropriately act as daily events

unfold? Imagine how exhausting life would be if we had to stop and think about every encounter

we had with a local person and about each word we uttered during the day. Anyone who has

lived for any length of time in a very different cultural setting knows of this experience. Often it

is called “culture shock.” We are not talking about the short, protected experience of a tourist.

We are talking about, for example, the experience of Peace Corps volunteers who spend two

years working in foreign environments, often in remote areas. We are talking about elderly

Native people whose whole life has been in the village of their ancestors but who now must go to

the city to find work or receive specialized medical care. And we are talking about the young

non-Native teacher who accepts a position teaching in an isolated Alaska Native village after

spending his entire life in New York City.

Part 3 – Social organization and cultural rules. If

a way of life – a culture – is

recognized as having distinctive elements closely shared by a group of people, than it must be

considered a living reality. Culture is not simply an abstract idea in some outside observer’s

mind. It is a real thing having real meaning and consequences for members

of the group. And to

have such meaning and consequences, the culture must have a social organization,

an institutional structure which at least meets the basic needs of the

group.

To identify a social institution we ask this question: Is there

a clearly defined category of people who repeatedly come together to accomplish

certain tasks or to regulate certain activities

of their society? In modern American society, for example, we have

religious institutions where various activities of the faithful take place

in churches,

temples, mosques, and synagogues on a

regular basis. Our capitalist economy is largely driven by the institution

of the private corporation. In all of these institutional settings, a clearly

defined category of people repeatedly

come together to accomplish a certain task. In traditional Native societies

we have such examples as the I˝upiaq and Siberian Yupik whaling crews, the potlatch among the Tlingit, and

the men’s house (qasegiq) among the Central Yup’ik. In each case the same category of people –

a whaling crew, a Tlingit clan or house group, Yup’ik men living in the same settlement – come

together on a regular basis to perform specific tasks.

Perhaps the most obvious social institution in any culture is

some form of a family. Within any cultural group we can detect a pattern of

how various

family members are expected

to treat each other as opposed to treating non-family members. This

also includes how to treat members of the larger kinship group such as aunts,

uncles, and cousins who may live in a

different household or even a different settlement. When viewed across

cultures, we can see different kinds of relationships between husband

and wife, between parents and children, or

between grandparents and grandchildren. Sometimes we can even identify

special relationships between aunts and their nieces and between uncles

and their nephews. In some societies there

exist clear cultural expectations of how older children shall care

for

their younger sisters and brothers.

Most important, all social institutions are governed by sets

of cultural rules. But what do we mean by cultural rules? We mean

those commonly understood principles and expectations which guide people’s behavior in everyday life. These rules, moreover, make up a large part of

that cultural road map we carry about in the back of our heads as we go about our daily routines.

It matters not whether the task is as routine as food preparation for the family or as dramatic as

preparing for war. Understanding family roles and relationships within a particular culture, for

example, becomes easier once we know the rules for how family members should relate to one

another — the son to the father, the granddaughter to the grandmother,

the husband to his wife. Of course we can reverse this investigative process.

We can try to understand the cultural rules

by observing over time the pattern of behavior that takes place among

family members

Part 4 – Culture persists over time. The

fourth idea helping to define our concept of culture is over time.

A distinct culture closely shared by a socially organized group of

people most likely

arose from adaptations their ancestors made to demands of a particular

natural and

social environment many years ago. As long as these environments

remain reasonably stable down through time, so too should a people’s social

institutions remain stable.

Such cultural stability was the historical condition of Alaska

Native life until the invasions brought sustained contact with powerful, culturally

different outsiders. This, however,

does not mean that pre-invasion Native life was without events

triggering

major social change for many Native communities. Indeed, the more

we learn about pre-contact Native life, the more

action-packed it becomes, filled with tales of hostilities between

Native groups that lasted for years and resulted in the death of many and the

dislocation of entire communities. Nevertheless,

such pre-invasion conflict and change was usually confined to a

region

and affected only several Native groups at any one time. Certainly

there was death and destruction in traditional times. But

it was not the basic social organization and cultural values of

the warring parties that was under attack. Even if beaten in battle or hit

by a natural

catastrophe, the customs and values of the

surviving people continued much as before. With the Russian and

American invasions, however, it was precisely Native social organizations and

cultural values that came under direct attack.

Part 5 – A

distinct speech community. The emphasis

here is on speech community, not

language as such. In both modern and traditional times, the way people

speak a language may be as significant a badge of cultural identity

as speaking

the language itself. A group of people may

speak the same language as other groups inhabiting the same general

culture area. But they speak and use it in ways that distinguishes

them from

these other groups. Consider the famous line

attributed to Winston Churchill, the British prime minister during

World War Two. He remarked that “Great Britain and the United States are two great democracies divided by a common

language.” If he were to use our terms, Churchill would reword his statement to say that Great

Britain and the United States share a common language but are two different speech

communities.

Although, for example, its basic vocabulary and grammar is commonly

shared by other American speech communities, the everyday English spoken by

many African-Americans can be

quite distinctive in its spoken style and vocabulary. In fact, words

and phrases used by many Americans have their origins in the “Black English” speech

community. Here are just a few examples: cat – originally

a jazz musician, now anyone of the male gender; cool – calm,

controlled; dig it – to understand, appreciate, pay attention; bad – really

good. The Head of the African and African-American Studies Department

at Harvard University, Henry Louis Gates Jr.,

makes this point:

“It [black English] becomes part of the mainstream in a minute," the poet Amiri

Baraka told me, referring to the black vernacular. “We hear the rappers say, 'I'm outta

here' - the next thing you know, Clinton's saying, 'I'm outta here.'" And both Senator John

Kerry and President George W. Bush are calling out, "Bring it on," like dueling mike-

masters at a hip-hop slam. Talk about changing places. Even as large numbers of black

children struggle with standard English, hip-hop has become the recreational lingua franca

of white suburban youth...2 [vernacular = everyday spoken language different from formal written

language.]

So, you might ask, what does certain characteristics of the African-American speech

community have to do with Native Alaska? We have known for many years that there is an

increasing shift from Native languages to English. Those who believe that “to lose your language

is to lose your culture” see this language shift as spelling doom for Native cultures. This grim

view of a Native future seems to forget two things. The first is the distinctiveness of Native

village life historically based a subsistence way of life no matter what language is spoken. The

second is the development of various forms of “Alaska Native English.” Consider the following

question: Like African-Americans, is there now emerging in Alaska different Native-English

speech communities? Perhaps we are at a point in Native history when, for example, a person

from an Athabaskan village can say, “Aha, the way that guy speaks and uses English tells me he

is, like me, a Koyukon Athabaskan from the Nulato area!”

We have taken time to discuss the idea of speech community because

it is a key feature of any culture, whether in modern or traditional times.

No concept of culture is complete without

some discussion of linguistics – of a group’s language and its characteristics. It is true that

language shifts and the development of new speech communities were not major issues in

traditional Native times. Bear in mind, however, that even back in those days the particular way

one spoke I˝upiaq or Tlingit or any other Native language would reveal one’s home community

or region to other speakers of same language, perhaps signaling whether that person is friend or

foe.

Part 6 – Worldview is the heart of culture.

This sixth element is absolutely central to any description of a cultural group.

A people’s worldview is the unique way they think of

themselves and make sense of the world they know. It deserves special attention. This is why all

of Chapter Seven is devoted to worldview and its various elements. For a definition of

worldview we go to the work of the late Oscar Kawagley, a Central Yup’ik scholar. In his book,

A Yupiaq Worldview, Dr. Kawagley says:

A worldview consists of the principles we acquire to make sense of the world

around us. Young people learn these principles, including values, traditions, and customs,

from myths, legends, stories, family, community, and examples set by community

leaders...

...Once a worldview has been formed, the people are then

able to identify themselves as a unique people. Thus, the worldview enables

its

possessors to make sense of the world around them, make artifacts [material

things] to fit their world, generate behavior, and interpret their experiences.

As with

many other indigenous groups, the worldviews of the traditional Alaska

Native peoples have worked well for their practitioners for thousands of

years. 3

Worldview is indeed is the heart of our concept of culture. Why? Because it provides a

everyday meaning and legitimacy to a group’s social institutions and cultural identity. It is their

worldview that defines, even celebrates, the group’s best image of itself. It describes and

promotes what is regarded as the proper attitude toward the spiritual world, the social world of

fellow humans, and the natural world and its living creatures.*

As suggested by Professor Kawagley, much of a culture’s worldview is revealed by what

adults insist be taught to the young. Whether modern or traditional, every society down through

time has established institutions to educate the young in all aspects of the group’s worldview.

The long-term survival of any culture and cultural identity ultimately depends on how effectively

a coherent worldview is passed down from generation to generation. In modern society, for

example, we have schools, youth organizations, and children’s television programs like Sesame

Street. In one form or another, these American institutions teach cultural values as well as skills

and information.

In traditional Native societies it was other kinds of institutions

which performed vital educational functions. Among the matrilineal societies

of southern Alaska, for example, there

existed an important educational institution called the avunculate. In

matrilineal kinship systems a person traces genealogical descent through the

mother’s side. In the matrilineal society of the

Tlingit, for example, a person’s most significant kinship ties are with members of the mother’s

clan. Personal benefits such as inheritance, property rights, and social status are tied to clan

membership. In patrilineal societies, on the other hand, a person’s significant kinship ties and

benefits are determined by genealogical descent on the father’s side. European monarchies, for

example, traditionally used patrilineal descent to establish who, male or female, ascended to the

royal throne as king or queen. [Genealogy: tracing one’s family history back to earliest ancestors.]

The avunculate found in matrilineal societies refers to the relationship

between the mother’s brother and her son. In Western terms, it is the relationship between a nephew and his

uncle on the mother’s side. This avuncular relationship is considered an educational institution

because it was the uncle’s responsibility to oversee the education and training of his sister’s son

who, of course, is his nephew. The biological father certainly has parental responsibilities to his

son, and the son had a special connection to his father’s clan. But we should not forget that he

also had avuncular educational responsibilities within his own clan to his sister’s son. In modern

educational terms, the avuncular relationship was like having your own personal instructor in a

home schooling situation. This was a fundamental cultural rule. It was a major way the group’s

values and knowledge were transmitted to the next generation of males.

Summary lesson. Our six-part concept of culture should remind us that Alaska Natives

persisted as culturally organized communities from ancient times. It suggests that this cultural

cohesion could only have happened if the group’s institutions and cultural rules continually met

the essential human needs of its members under demanding environmental conditions.

Review Questions.

How have we defined the concept of culture?

Why do we have “speech community” rather than language

as one of our six parts of culture?

Can you give some examples of cultural rules you follow in

your own daily life without having to constantly thinking

about them?

Why do we consider worldview to be the heart of any

people’s culture?

ENDNOTES

Suggested Readings:

Major Ecosystems of Alaska (Anchorage:

Joint Federal-State Land Use Planning Commission for Alaska, 1973).

Joan Townsend, “Ranked Societies of the Alaskan Pacific Rim,” Senri

Ethnological

Studies, 4, 1979, pp 123–156.

This chapter gets you started on the

Cultural Profile of your selected Native group or groups. It provides

you with an instructional

guide for profiling the elements of the environment shown above. They

are exactly the same as listed in the Cultural Profile Project Outline on page

three. The

chapters to come on Land Use and Occupancy, Social Organization, Worldview,

and Cultural Products offer similar instructional guidance for completing

your project. You will find, however, that this and the remaining chapters

offer

much more than a simple guide. As said before, we want to carefully explain

the concepts we use to organize our thinking about Native societies in

traditional

times. What exactly do we mean, for example, when we use concepts like

environmental adaptation or land-use patterns or social stratification or governance

or

shamanism?

Describing elements of a regional environment is

fairly straight forward. The climate, topography and so forth are much the

same today as they

were in traditional

times. It needs mentioning, however, that today’s climate appears

to be undergoing significant change. As climate changes, so also will

topography,

flora, and fauna. It presents new environmental conditions to which

humans must adapt. Retreating arctic sea ice and its impact on Eskimo

whaling

is an example. For purposes of this assignment we assume basic elements

of today’s

regional environments still closely resemble those of traditional times.

The

Big Picture

South vs. North. The first thing to notice at the

beginning of this chapter is the line of arrows ↓↓ pointing

down from Regional Environment

to Land

Use and Occupancy (Chapter 7), Social Organization

(Chapter

8), and

Cultural products

(Chapter 10). The arrows are intended to

emphasize the idea that elements of the environment set the parameters,

the outer limits, of what environmental

adaptations were possible for subsistence-based Native societies

occupying

that region. Again, the amount and kind of subsistence and material

resources available in a particular environment largely determined

what that Native

society

looked like demographically, socially, and technologically. The Aleuts,

for example, could do things within their maritime island environment

that Interior

Athabaskans could not do within their landlocked sub-Arctic environment.

Of course interior Athabaskans could do things that Aleuts could

not.

Now let’s take a moment to paint the broadest

possible picture of the relationship between Alaska’s different environments

and the social organizations of Native groups inhabiting these areas. Look

at any map of Alaska

which shows

the Alaska Range. Denali (Mt. McKinley) is the best known topographic

feature of this mountain range which stretches across Alaska from east to

west. Now

draw or imagine a line along the top of the Alaska range. South

of that line – south

of the Alaska Range – we find very different environments

and traditional Native social organizations from what we find north

of

the Range.

The South. Easy year-round access

to abundant marine resources in the oceans and rivers south of the

Alaska range supported larger

Native

populations. It is true that in important ways the southern Alaskan

regional environments

of

the Aleut and the Tlingit are different. The Aleuts lived mainly

on barren, windswept islands and the Tlingit in areas of high mountains,

old growth

forests, and sheltered bays and coves. But the important point

is

that

both of these

very different regional environments yielded a steady supply, even

surpluses, of subsistence marine resources.

Not only were southern

Native populations larger but their settlements were more densely populated

and more permanent than those found

in the north.

By “densely

populated” we mean a large concentration of people within

an given area. There are, for example, many more people living

within each square

mile of

New York City than people living within each square mile of Fairbanks,

Alaska. Their settlements, moreover, were much more permanent

because they had easy

access to their subsistence resources throughout the year. Unlike

many northern Native societies, people did not have to move with

the seasons or spend weeks

on a hunting or fishing expedition just to meet the basic dietary

needs of their families. To say that their primary subsistence

resources lay just

outside their front door is not much of an exaggeration.

When

added together, these factors — large, permanent, densely

populated settlements with abundant resources — led to

the development of a more elaborate social organization to regulate

tribal affairs. Certainly we will

find more and larger government departments and neighborhood

institutions such as churches and schools in New York than in

Fairbanks. Another prominent feature

of the more complex southern Native societies was their hierarchical

social structure. A hierarchical or ranked society exists when

there is an unequal

distribution of wealth, power, and social status among different

classes of people. When we ask about the structure and distribution

of wealth, power,

and social status, we are asking about a society’s social

stratification – its

system of social ranking.

The social stratification of southern

Native societies was based on the hereditary ranking of families

and clans. This meant that

the social

status of the family

and clan into which a person was born largely determined what

social and economic advantages were available to that person,

both as

a child and

later as an adult.

General speaking, these ranked societies consisted of an aristocracy

of clans at the top of the social pyramid, with commoners occupying

the

middle

and lower

reaches of society. In all southern Native hierarchical societies,

the lowest social rank or class was occupied by slaves obtained

through war

and trade.1

Here is another important point. Because of very

accessible and abundant resources, not everyone had to be involved in

the daily

round of

subsistence activities.

This meant that certain individuals possessing special talents

could devote a major portion of their day to work other than

subsistence hunting, fishing,

and gathering. Consequently there arose occupational specialization

in important areas such as medicine, arts and crafts, spiritual

leadership,

political organization,

and in the conduct of war and commerce. If the knowledge

and skills of

a particularly talented person became highly valued, he or

she could concentrate time and

energy on that specialty while their subsistence needs were

provided for by their household group, their clan, or even

payment for

services by others

within

the larger community.

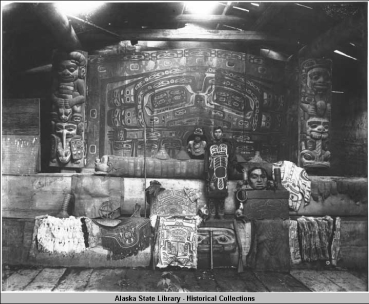

Figure 5-1

Interior of Whale House of Chief Klart-Reech, Klukwan,Alaska. c.

1895.

Among the Tlingit, for example, the most basic social

unit at the local level was the household group. It consisted of men of the

same matrilineal line and their families living together in very large wooden

plank-and-beam houses (See Figure 5-1). Sometimes these “longhouses” were

as large as 40 x 60 feet. (A full-size basketball court measures 50 x 84 feet).

The head of the household group usually did not physically participate in subsistence

activities. He had instead a full time job as the political and ceremonial

leader of the household and as their chief historian and educator.

If their

skills were especially prized, individuals could gain wealth and privilege

ordinarily reserved for those of a higher hereditary rank. The possibility

of upward social mobility through demonstrated expertise in a valued specialty

was certainly important to slaves. It was one way they could rise above their

wretched social rank and avoid a life of despair and the possibility of being

sacrificed at a potlatch. In a word, there existed a more elaborate division

of labor based on occupational specialization than we find in northern Native

societies.

The North. With some exceptions,

the often seasonally marginal subsistence resources found north of the Alaska

Range – particularly

for interior Athabaskans – meant smaller, more mobile Native populations

spread over large areas. In contrast to the south, there was far less permanence

and density

of settlements. The exceptions were some Central Yup’ik areas around

Bristol Bay and in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta. In fact, the Central Yup’ik

region has been described as a “transitional zone” between

north and south because it has environmental features found in both.2 Another

exception

was the Point Hope region of Northwest Alaska in the early 1800s. At that

time the area’s subsistence resources, mainly marine mammals and

fish, sustained a large settlement area estimated at 1,000 people.3

For

the most part, the social stratification of northern Native societies

was more egalitarian in structure. Unlike the social hierarchies of the

south, there was no easily identifiable ranked social order where power

and privilege

differed significantly among classes of people. Normally birth into a

particular family was not the chief factor determining a person’s opportunities

in life and future adult social standing. The northern societies offered

a more level socio-economic playing field to all members of the group.

Unlike

the southern hierarchical society, individual effort and merit were more

likely to determine a person’s social status. The institution of

slavery, moreover, did not exist north of the Alaska Range.

Because everyone

was always involved in some part of the harvesting and preparation of

subsistence foods and material products, less time was

available to develop

the kind of occupational specialization that occurred in the south. This

does not mean there was no specialization or no development of specialized

knowledge

in the north. Every Native group had to develop the necessary science

and technology to successfully meet the unique demands of their environments.

We should not

be surprised that expertise in weather forecasting and in animal behavior

are well developed areas of traditional Native science throughout Alaska.

Examples

of Native technologies included the construction of sea worthy hunting

craft such as the kayak and umiak, various hunting tools and weaponry,

protective

battle vests, weather resistant housing, dog sleds and snowshoes. We

will

have a fuller discussion of Native applied science and technology when

we discuss

cultural products in Chapter Ten.

Social stratification: beware of false

dichotomies. We have said that social stratification refers to the

structure of wealth, power, and social

rank

in society. We have discussed two seemingly opposite forms of traditional

Native

social stratification — the southern hierarchical societies versus

the northern egalitarian societies. In so doing, however, we must be

careful not

to create a false dichotomy by implying that these are two quite separate

and distinct systems of social stratification. The word “dichotomy” means

the separation of a thing or idea into two opposite parts. A dichotomy

is an either-or proposition — it is either this thing

or that thing. It is either apples or oranges.

So what is the problem?

The problem is that there is no such thing

as a purely hierarchical society or purely egalitarian society, either

in

modern

or traditional

times. What we have are human societies which are more – sometimes

much more – hierarchical than egalitarian and vice versa. And

when we talk about the more or less of things, we are talking about

variables. Variables

are not absolute and permanent things. They are constantly influenced

by other factors and therefore always subject to change. In the real

world, social stratification

is very much a variable because any society can have a mix of hierarchical

and egalitarian elements. As much as its members may wish or claim,

no society is completely egalitarian. Some form of social ranking is

always present. Some

individuals or families or groups in society have more power and resources

than others.

In their study of reindeer herding and social change

among the Iñupiaq

of the northern Seward Peninsula, the late Linda Ellanna and her co-author,

George Sherrod, emphasize this important social fact. Their study even

includes a chapter entitled “The Myth of the Egalitarian Society” in

which they detail how wealth and power were never distributed evenly.

Nor did the

Inupiat expect to live in a purely egalitarian community. There were

always some who were more clever and more ambitious than others. There

were always

some families who prospered more than other families and passed these

advantages on to later generations. Ellanna and Sherrod make this interesting

observation

on control of vital subsistence technologies and key hunting and fishing

sites:

Technologies employed in collective harvesting endeavors

included umiat [skin boat], caribou surrounds, and fish weirs and nets. These

items

of technology

were not owned by the society nor owned equally by all segments of

a large extended local family. Instead, this technology was associated … with

the eldest productive male of the group possessing the skills, knowledge,

and wealth necessary to supervise construction, maintenance, and use

of these means

of production. Additionally, this individual and his closest kin controlled

key geographic sites from which these technologies were deployed.4 [Emphasis ours]

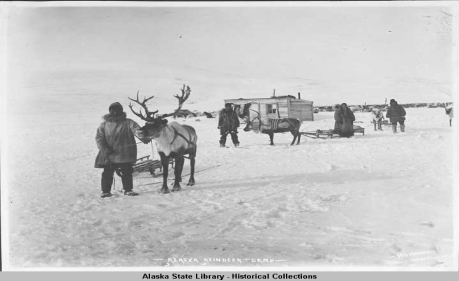

Figure

5-2

Alaska Reindeer Camp, c. 1913

In the South, the occupational specialization of

the Tlingit and Haida hierarchical societies did allow for the egalitarian

element of upward social mobility. No matter the status of one’s family

or clan, an individual could achieve a higher social rank based on demonstrated

merit – on proven ability and accomplishment in an occupation or

skill valued by the society. Moreover, a society’s social order can be

changed by historic events such as internal revolts and revolutions or by external

forces such as invasion and occupation by a foreign power. In 1886, for example,

a federal court ruled that the 13th amendment of the United States Constitution

prohibiting slavery also applied to Tlingit and other Native groups regardless

of what inherent tribal sovereignty they may otherwise possess. Obviously this

legal ruling significantly changed Tlingit society by removing a major social

and economic stratum — slaves —from their traditional hierarchical

structure.5

So we must learn to think in terms of more or

less hierarchy or egalitarianism, not in terms of either – or ,

not in terms of either a completely hierarchical or a completely egalitarian

society. Some argue,

for example, that despite

its ideal values of equality and the rule of law, the social stratification

of American society falls somewhere between hierarchical and egalitarian

because it has characteristics of both social structures. Please understand

that we

use the dichotomy of hierarchy versus egalitarian only as a starting point,

only as a framework for thinking about the different kinds of social stratification

that may exist. If you are doing a cultural profile of a northern Native

society, do not hesitate to look hard for elements of social ranking. Likewise,

if you

are researching a southern Native society, look hard for elements of egalitarianism

such as social mobility – the ways individuals could rise above or

fall below the social rank of their birth.

A false dichotomy in modern Native

times. A good example of a widely held

dichotomy misrepresenting Alaska Native life today is traditional versus

modern. One

harmful example of this unfortunate dichotomy arose in the 1970s when the

Bowhead whale was declared an endangered species and many people in other

parts of

the world said Eskimo whaling should be completely stopped. They argued

that it was no longer a “traditional” subsistence activity because

Umialiks (whaling captains) and their crews use modern hunting gear such

as harpoon

bombs and modern transportation devices such as outboard motors. They further

argued that the nine Alaska Eskimo whaling communities now have many modern

conveniences such as electricity and access to store-brought foods as well

as other consumer goods. Therefore these Iñupiaq and Siberian Yupik

whaling communities lead modern lives and can no longer claim a cultural

or economic need for subsistence whaling.

Of course these outsiders knew

little about the vital role whaling has always played within the subsistence

culture and economy of Eskimo whaling

communities.

What they did not understand or chose to ignore is described by the Inuit

Circumpolar Conference (ICC):

The size of the (bowhead) whale makes it

an important part of the annual subsistence harvest. The taste of the various

parts of the whale makes

it prized as food.

The communal nature of the hunt and the sharing of the whale give it

a central place in the spiritual and physical culture of the region.

The

bowhead provides

life, meaning, and identity to the Eskimo whalers and their communities.

Sharing

the whale with the whole community, and with other communities too, is an

old and highly- valued practice. At the butchering site,

the parts

of the

whale are divided among the whaling crews, with some shares reserved

for elders and widows and other parts kept for festivals. At these

festivals,

including

Thanksgiving and Christmas as well as the traditional feasts of Nalukataq

and Qagruvik, the food of the whale is given to everyone who comes

to take part.

In this way, tons of meat find their way throughout the region all

year long.6

Outside pressure on Alaska Eskimo whaling communities

intensified in 1977 when the International Whaling Commission (IWC) imposed

a

complete

ban

on Eskimo

whaling. The IWC ban was in response to scientific reports that the

bowhead whale population

had fallen to a total of 2,000, maybe even as low as 600. Not long

after, the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission (AEWC) was organized.

Its members

were Umialiks

representing the nine whaling villages and they quickly went into action.

They disputed these numbers, arguing that they were much too low, and

that the ban

did considerable harm to the health and culture of their whaling villages.

But they were only successful in getting the IWC to shift from a complete

whaling ban to a small quota of allowable whale strikes. The key term

here is “strikes”.

Obviously “to strike” a whale does not guarantee that you

will ultimately harvest that whale. A whale may survive the strike

and escape, which means you

have used up one of your allotted strikes and achieved no benefit.

If they were to abide by this international rule yet meet their subsistence

needs, Eskimo

whaling crews had but one option — to use the most modern and

effective equipment to ensure that a whale struck was a whale harvested.

This

increased use of modern devices gave still more ammunition to all those

outsiders pressing for a end to all whaling, including that

done

by subsistence-based

indigenous communities throughout the Arctic. Many of these people

were members of large, well organized, and powerful environmental and

animal

rights groups.

So the political pressure was immense and the Eskimo whalers were trapped

in the dilemma of “damned if you do and damned if you don’t.” If

they didn’t use modern equipment, they could not close the strike – harvest

gap. On the other hand, if they did use the latest equipment, then

they were labeled “modern” and judged to have no essential

ties to the cultural traditions and nutritional benefits of whaling.

The

dichotomy is proven false. After a series of confrontations

with federal officials, the AEWC reached an agreement with The National

Oceanic and

Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the federal agency responsible for

managing whale

protection. In 1981, NOAA delegated to the Umialiks of the AEWC management

authority over

Eskimo whaling. This allowed the AEWC to manage the hunt without the

presence of federal agents in whaling communities. Today it is the

Umialiks who

supervise whale hunting in the nine whaling communities and report

to NOAA.

Using traditional Eskimo knowledge of whale behavior

along with modern

scientific technology, there are now much better methods for estimating

the population

of bowheads. As a result, the ICC reported in 1992 that the population

level of

bowheads was increasing and no longer a cause for concern. This has

helped the whalers secure increased quotas based on the subsistence

needs of

the whaling villages. In cooperation with NOAA, a Whaling Weapons Improvement

Program was

organized in an effort to increase the safety and reliability of whaling

weapons and equipment. One example is use of a float equipped with

a radio

transmitter

to find whales in fog and rough water.7

After years of political strife

and cultural distress, it is now understood that thinking based on the traditional – modern

dichotomy greatly distorts the realities of Eskimo whaling cultures. The

dichotomy was also found to be a major

obstacle to resolving the international issue of how to maintain

healthy bowhead whale populations. By using traditional Eskimo knowledge

of whale behavior

along

with modern marine science, this ancient culture of the Arctic and

the whale population on which it depends has a much better chance of survival.

A South – North summary. We

can compose a brief outline to summarize the contrast between the north and

the south. The symbol ↓ means “results

in”.

Southern Native societies (south of the

Alaska Range)

Abundant subsistence resources, even to the point

of producing surpluses

↓

Larger, more permanent and more densely settled Native communities

↓

Hierarchical societies with an uneven distribution of power and wealth,

with a more complex division of labor based on occupational

specialization

Northern Native societies (north of the Alaska

Range)

With some exceptions, marginal, sometimes scarce

subsistence resources

↓

Smaller, more mobile and sparsely settled Native communities

↓

More egalitarian social organization with much less division

of labor based on occupational specialization.

Interior Athabaskans

and Southern Athabaskans. In traditional times the only social

facts the Interior Athabaskan groups north

of the

Alaska Range had

in common with the Tanaina and Copper River Ahtna Athabaskans

of the south was

language and ethnicity. On the broad cultural profile factors

of regional environment, land use and occupancy, and social organization,

Tanaina

and Copper River Ahtna

life more closely resembled the other southern Native societies.

In the

North, the life of the Interior Athabaskans more closely resembled

other northern

Native

societies.

Special features of the regional environment. Some

features of the regional environment require special attention. These

are

features which “set up” the

significance of certain elements of Social Organization and Cultural

products later in your Cultural Profile. The fauna [animal

life]

of any Native group’s

region is probably the most obvious set-up element because people’s

lives were almost totally organized around hunting and fishing.

A clear description

of the area’s fish and game resources therefore sets

up what you later say about how the group organized

its hunting and gathering, what were their

primary and secondary subsistence resources, and what hunting

and fishing materials were necessary for success.

But there may

be other set up features also requiring special attention. If

you choose to profile the coastal Iñupiaq, for example,

you will describe the usual topographical features of mountains,

valleys, and rivers. Of course

you will do this for whatever Native group you are profiling.

But for the coastal Iñupiaq, an equally significant but

often overlooked topographical feature of their environment is

sea ice. Think about the relationship between sea ice

and Iñupiaq life. Does not much of the coastal Iñupiaq

subsistence activities – from seal hunting to whaling – depend

on sea ice conditions? If so, then the social and technological

adaptations made by the Iñupiaq

to different sea ice conditions were absolutely crucial for establishing

a way of life that went beyond mere survival. Therefore a more

detailed picture of

sea ice and its seasonal changes is necessary to set up your

later descriptions of coastal Iñupiaq social organization

and cultural products.

Environmental adaptation: a summary. The

first thing your Cultural Profile must do is describe the regional

environment to which

your selected Native

group had

to make adaptations over time. In later chapters you will go

below the line of arrows to land use, social Organization and

cultural

products and describe

how the Native group made these necessary adaptations.

Environmental adaptation is the concept tying together all

these elements.

And again, we mean

by this concept

the process by which a Native society socially organized itself

and developed

the technology and knowledge to effectively harvest the resources

of its region. Obviously a Native group had to have the right

hunting and fishing

technologies

to survive within a particular environment. What may not be

so obvious is that Native groups first had to socially organize

themselves in

ways that

a) maintained

the most effective member participation in harvesting of subsistence

resources, and b) most effectively distributed these resources

among its members according

to the values and traditions of the group.

Note, finally, that

already we are discussing different ways Native societies

were organized. Even with the social organization

part

of the Cultural

Profile still several chapters away, we are already using

terms like social stratification,

hierarchical societies, egalitarian societies. Why? Because

significant features of social life in traditional times

were shaped by the

nature of the environment.

It was imperative that Native groups socially organized themselves

in ways that took best advantage of the opportunities of

their environment while

avoiding the dangers.

Review Questions.

Can you define environmental adaptation and explain

how this process works?

Can you explain the major differences between Northern

Native societies and

Southern Native societies and the way different environments shaped

the nature of these societies?

Why do we say beware of false dichotomies when

studying Alaska Native life in traditional as well as in modern times?

Why have we been forced to look at aspects of traditional

Native social life long before we get to the chapter on Social Organization?

* Professor Kawagley employs the appellation Yupiaq when referring

to Central Yup’ik people. In his Native People of Alaska, Steve

Langdon favors Yupiit.4 To be consistent throughout our project, we

stick with the Alaska Native Language Center’s appellation of Central

Yup’ik. [Appellation: the name by which someone or some group is

known.]

ENDNOTES

-

The idea that cultural knowledge largely consists of mundane, taken

for granted, often invisible rules governing social interactions in everyday

life is well explained in the works of James Spradley and David McCurdy.

See their: The Cultural Perspective. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press.

1989. Also see: Susan Philips The Invisible Culture: Communication

in Classroom and Community on the Warm Springs Indian Reservation (Long

Grove, Ill:Waveland Press,1992).

-

Henry Louis Gates Jr. ”Axing a Few Questions About Black

Vernacular,” New

York Times, October 2004.

-

Oscar Kawagley, A Yupiaq Worldview (Prospect

Heights, IL: Waveland Press. 1995) pp. 7-8.

-

Steve Langdon, Native

People of Alaska (Anchorage: Greatland Graphics, 5th edition,

2002).

Table of Contents | Chapter

6

The

University of Alaska Fairbanks is an Affirmative

Action/Equal Opportunity employer, educational

institution, and provider is a part of the University of Alaska

system. Learn more about UA's notice of nondiscrimination. The

University of Alaska Fairbanks is an Affirmative

Action/Equal Opportunity employer, educational

institution, and provider is a part of the University of Alaska

system. Learn more about UA's notice of nondiscrimination.

Alaska Native Knowledge

Network

University of Alaska Fairbanks

PO Box 756730

Fairbanks AK 99775-6730

Phone (907) 474.1902

Fax (907) 474.1957 |

Questions or comments?

Contact ANKN |

|

Last

modified

July 6, 2011

|

|