|

CULTURE, COMMUNITY AND PLACE IN ALASKA NATIVE EDUCATION

by

Ray Barnhardt

University of Alaska Fairbanks

Barnhardt, R. (2005). Culture, Community and Place in Alaska Native

Education. Democracy and Education, 16(2), pg. ? (forthcoming).

Education in one form or another has been an essential ingredient

contributing to the cultural and physical survival of the Indigenous

peoples

of Alaska for millennia. The accumulated knowledge systems,

world views and ways of knowing derived from first-hand engagement

with an oftentimes harsh and inscrutable arctic environment have

been

integrated into the fabric of the Indigenous societies and

passed

on seamlessly from one generation to the next in the course

of everyday life. Education in its traditional forms continues

to

be an integral part of Alaska Native cultures and communities.

With the arrival of the early explorers, traders, missionaries

and teachers, a collision of world views occurred, including the

introduction

of competing ways of learning about and understanding the world

in which people lived, thus disrupting the balance in the traditional

system. Gradually, a new way of educating was introduced in

the form of –schooling,” operating on the assumption that the introduction of western ways through western institutions would transform Native people into citizens of the –modern” world. However, after 100 years this –new” system

has been found wanting on the river banks and ocean shores that

Alaska Native people call home, often marginalizing traditional

practices and providing for neither the cultural nor the academic

well-being of many of the Native students entrusted to its care.

As a result of the many years of continued frustration and broken

promises at the hands of outside educational experts, Native

people themselves are now asserting their own ideas for transforming

schooling

into a more culturally adaptive form of education, and they

are finding ways to improve the quality of education for all students

in the process. The remainder of this article will describe

how

schools throughout Alaska are being refocused by bringing together

the deep traditional knowledge of Alaska Native people with

the Western-based constructs, principles and theories imbedded

in conventional

curricula. The long-standing democratic principle of local

control of education is being brought to bear on schools in rural

Alaska

through the bottom-up educational reform strategy of the Alaska

Rural Systemic Initiative, while at the same time Native communities

are grappling with the top-down pressures of current federal

mandates.

The Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative (AKRSI) was established

in

1994 under the auspices of the Alaska Federation of Natives,

which has served as the institutional home base and support structure

for the AKRSI in cooperation with the University of Alaska,

with

funding from the National Science Foundation. The purpose of

the Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative has been to implement a set

of

initiatives that systematically document the Indigenous knowledge

systems of Alaska Native people and develop pedagogical practices

that appropriately integrate Indigenous knowledge and ways

of knowing into all aspects of the education system. In practical

terms, the

most important intended outcome is an increased recognition

of the complementary nature of Native and western knowledge, so

both

can be effectively utilized as a foundation for the school

curriculum and integrated into a more comprehensive approach to

education

that is grounded in the existing cultural and physical environment

in which students live.

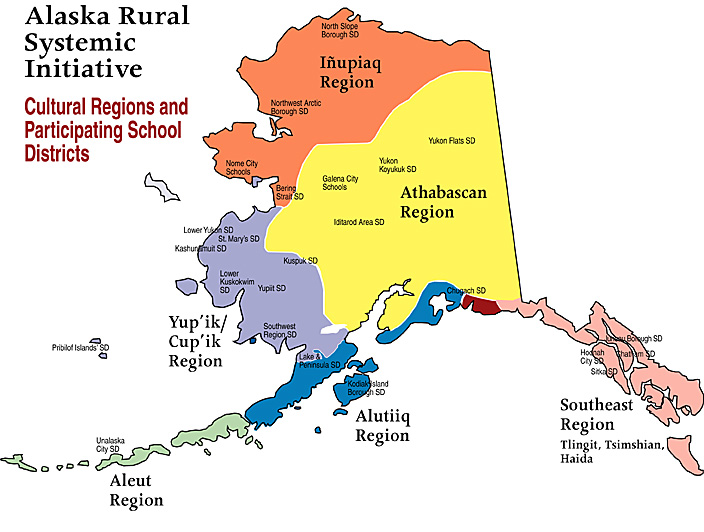

The AKRSI initiatives themselves are implemented on a rotational

cycle organized in reference to the major cultural regions that

make up Alaska,

so that the educational components are tailored to fit the

particular cultural context in which they are situated. The following

map

illustrates the geographic spread of the various Alaska Native

cultural groups, as well as the school districts in each region

that have been participating in the initiatives.

The central focus of the AKRSI reform strategy is the fostering

of connectivity and complementarity between two functionally interdependent

but largely disconnected complex systemsãthe Indigenous knowledge systems

rooted in the Native cultures that inhabit rural Alaska, and the

formal education systems that have been imported to serve the educational

needs of rural Native communities. Within each of these evolving

systems is a rich body of complementary knowledge and skills that,

if properly explicated and leveraged, can serve to strengthen the

quality of educational experiences for students throughout rural

Alaska (Boyer, 2005).

Indigenous Knowledge Systems

The 16 distinct Indigenous cultural and language systems that

continue to survive in rural communities throughout Alaska have

a rich cultural

history that still governs much of everyday life in those communities.

For over six generations, however, Alaska Native people have

been

experiencing recurring negative feedback in their relationships

with the external systems that have been brought to bear

on them, the consequences of which have been extensive marginalization

of

their knowledge systems and continuing dissolution of their

cultural integrity. Though diminished and often in the background,

much

of the Native knowledge systems, ways of knowing and world

views remain intact and in practice, and there is a growing appreciation

of the contributions that Indigenous knowledge can make to

our

contemporary understanding in areas such as medicine, resource

management, meteorology, biology, and in basic human behavior

and educational practices. Through long observation they have become

specialists in understanding the interconnectedness and holism

of all things in the universe (Kawagley, 1995; Barnhardt

and Kawagley,

1999; Barnhardt and Kawagley, 2005).

Among the qualities that are often identified as inherent strengths

of Indigenous knowledge systems are those that have also been identified

as focal

constructs in the study of the dynamics of complex adaptive

systems. These are qualities that focus on the processes of interaction

between the parts of a system, rather than the parts in isolation,

and it is to those interactive processes that the AKRSI educational

reform strategy has been directed. In so doing, however,

attention

has extended beyond the relationships of the parts within

an Indigenous knowledge system and taken into account the relationships

between

the system as a whole and the other external systems with

which it interacts, the most critical and pervasive being the formal

education systems which now impact the lives of every Native

child,

family and community in Alaska.

The Formal Education System

Formal education is still an evolving, emergent system that is

far from equilibrium in rural Alaska, thus leaving it vulnerable

and malleable

in response to a well-crafted strategy of systemic reconstruction.

The advantage

of working with systems that are operating at the edge

of chaos is that they are more receptive and susceptible to innovation

and

change as they seek equilibrium and order in their functioning

(Barnhardt and Kawagley, 2004). Such is the case for many

of the educational systems in rural Alaska, for historical as

well

as

unique contextual reasons. From the time of the arrival

of the Russian fur traders in the late 1700ês up to the early 1900ês, the relationship between most of the Native people of Alaska and education in the form of schooling (which was reserved primarily for the immigrant population at that time) may be characterized as two mutually independent systems with little if any contact, as illustrated by the following diagram:

Prior to the epidemics that wiped out over 60% of the Alaska Native

population in the early part of the 20th century, most Native people

continued to live a traditional self-sufficient lifestyle with

only limited contact with fur traders and missionaries (Napoleon,

1991). The oldest of the Native Elders today grew up in that traditional

cultural environment and still retain the deep knowledge and high

language that they acquired during their early childhood years.

They are also the first generation to have experienced significant

exposure to schooling, many of them having been orphaned as a result

of the epidemics. Schooling, however, was strictly a one-way process

at that time, mostly in distant boarding schools and orphanages

with the main purpose being to assimilate Native people into Western

society, as practiced by the missionaries and school teachers (who

were often one and the same). Given the total disregard (and often

derogatory attitude) toward the Indigenous knowledge and belief

systems in the Native communities, the relationship between the

two systems was limited to a one-way flow of communication and

interaction up through the 1950ês, and thus can be characterized as follows:

Democratic principles were in short supply in these early years,

with virtually all decisions associated with schooling originating

outside the Native communities and cultures. By the early 1960ês, elementary schools had been established in most Native communities, and by the late 1970ês, a class action lawsuit had forced the state to develop high school programs in the villages throughout rural Alaska. At the same time (in 1976), the federal and state-operated education systems were dismantled and in their place over 20 new school districts were created to operate the schools in rural communities. That placed the rural school systems serving Native communities under local control for the first time, and concurrently a new system of secondary education was established that students could access in their home community. These two steps, along with the development of bilingual and bicultural education programs under state and federal funding and the influx of a limited number of Native teachers who began to bridge the cultural divide by incorporating the knowledge base from within the local communities in their teaching, created the potential for schools to become more than one-way conduits for Western ways. This opened the doors for the beginning of two-way interaction between schools and the Native communities they served, as illustrated by the following diagram depicting rural education by 1995 (when the AKRSI was initiated):

Despite the structural and political reforms that took place in

the 70ês and 80ês,

rural schools have continued to produce a dismal performance record by most

any measure, and Native communities continue to experience significant social,

cultural and educational dislocations, with most indicators placing communities

and schools in rural Alaska at the bottom of the scale nationally. While there

has been some limited representation of local cultural elements in the schools

(e.g., basket making, sled building, songs and dances), it has been at a fairly

superficial level with only token consideration given to the significance of

those elements as integral parts of a larger complex adaptive cultural system

that continues to imbue peoples lives with purpose and meaning outside the

school setting. Though there is some minimum level of interaction between the

two systems, functionally they have remained worlds apart, with the professional

staff overwhelmingly non-Native (95% statewide) and with a turnover rate averaging

30-40% annually.

With these considerations in mind, the Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative

has sought to serve as a catalyst to promulgate reforms focusing

on increasing the level

of connectivity and complementarity between the formal education

systems and the Indigenous knowledge systems of the communities

in which they are situated.

In so doing, the AKRSI has sought to bring the two systems together

in a manner that promotes a synergistic relationship such that

the two previously separate

systems can join to form a more comprehensive holistic system that

can better serve all students, not just Alaska Natives, while at

the same time preserving

the essential integrity of each component of the combined over-lapping

system. The new combined, interconnected, interdependent, integrated

system to which

AKRSI has aspired may be depicted as follows:

Forging an Emergent System of Education for Rural Alaska

In May, 1994 the Alaska Natives Commission, a federal/state task

force that had been established two years earlier to conduct a

comprehensive review

of programs and policies impacting Native people, released a report

articulating the need

for all future efforts addressing Alaska Native issues to be initiated

and implemented from within the Native community. The long history

of failure of

external efforts to manage the lives and needs of Native people

made it clear that outside interventions were not the solution

to the problems, and that

Native communities themselves would have to shoulder a major share

of the responsibility for carving out a new future. At the same

time, existing government policies

and programs would need to relinquish control and provide latitude

and support for Native people to address the issues in their own

way, including the opportunity

to learn from their mistakes. It is this two-pronged approach that

is at the heart of the AKRSI educational reform strategyãNative community initiative coupled with a supportive, adaptive, collaborative education system.

One of the most significant initiatives to come from the Native

community was the adoption of a set of –cultural standards” that

were developed by Alaska Native educators and Elders to provide explicit guidelines

for how students, teachers, curriculum, schools and communities could integrate

the local culture and environment into the formal education process so that students

would be able to achieve cultural well-being as a result of their schooling experience

(http://ankn.uaf.edu/publications/standards.html). The focus of these cultural standards has

been on shifting the emphasis in education from teaching about culture to teaching

through the local culture as a foundation for all learning, including the usual

subject matter.

The key agents of change around which the AKRSI educational reform

strategy has been constructed are the Alaska Native educators working

in the formal education

system coupled with the Native Elders who are the culture-bearers

for the Indigenous knowledge system. Together, the Native educators

and Elders have served as catalysts

to reconstitute the way people think about and do education in

rural schools throughout Alaska. The role of the Alaska Rural Systemic

Initiative has been

to guide these agents through an on-going array of locally-generated,

self-organizing activities that produce the organizational change

needed to move toward a new

form of emergent and convergent system of education for rural Alaska.

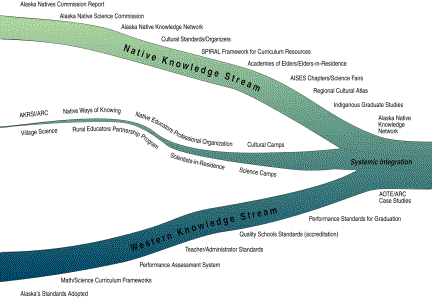

The overall configuration of this emergent system may be characterized

as two interdependent

though previously separate systems being nudged together through

a series of initiatives maintained by a larger system of which

they are constituent parts,

as illustrated in the following diagram:

Each of the AKRSI initiatives serves to guide the streams toward

a mutually compatible and complementary relationship. For example,

the Alaska Native Knowledge Network

assembles and provides easy access to curriculum resources that

support the work underway on behalf of both the Indigenous knowledge

system and the formal education

system (http://www.ankn.uaf.edu). In addition, the ANKN newsletter,

Sharing Our Pathways, provides an avenue for on-going communication

between all elements

of the constituent systems. Concurrently, the AKRSI has been collaborating

with the Alaska Department of Education and school districts in

bringing Native educators

from the margins to the center of educational decision making to

shape policy development in ways that take into consideration the

cultural context in which

students acquire and demonstrate their knowledge, using the cultural

standards as a guide.

Together, these initiatives constitute the core strategy of the

Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative and are intended to generate a

strengthened complex adaptive

system of education for rural Alaska that can effectively integrate

the strengths of the two constituent emergent systems. The exact

form this integrated system

will take remains to be seen as its properties emerge from the

work that is underway. Accepting the open-endedness and unpredictability

associated with such a change

process, and relying on the emergent properties associated with

the adage, –think globally, act locally,” we

are confident that we will know where we are going when we get there.

Cultural Intervention Strategies

The overall structure of the Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative

is organized around the following cross-cutting themes that integrate

the initiatives

within and across each of the major cultural regions:

Alaska Native

Knowledge Network

Indigenous Science Knowledge Base

Multimedia Cultural Atlas Development

Native Ways of Knowing/Pedagogical Practices

Elders, Cultural Camps and Traditional Values

Village Science Applications, Camps and Fairs

Alaska Standards for Culturally Responsive Schools

Native Educator Associations

Academies of Elders

Adopting the emphasis that these initiatives bring to engaging

students in the study of culture, community and place, schools

across the state

have been engaged in common endeavors that unite them, at the same

time that they are concentrating

on particular initiatives in ways that are especially adapted

to the Indigenous knowledge base in their respective cultural region.

Each set of initiatives and

themes have built on each other from year to year and region

to region through a series of statewide events that bring participants

together from across the

regions. These include working groups around various curriculum

themes, Academies of Elders, statewide conferences, the AKRSI staff

meetings and the Alaska Native

Knowledge Network. Following is a brief description of some of

the key AKRSI-sponsored initiatives to illustrate the kind of activities

that have been implemented,

as they relate to the overall educational reform strategy outlined

above.

Alaska Native Knowledge Network - A bi-monthly newsletter,

web site and a culturally-based

curriculum resources database have been established to disseminate

the information and materials that have been developed and accumulated

throughout Alaska (http://www.ankn.uaf.edu).

S.P.I.R.A.L. Curriculum Framework - The ANKN curriculum clearinghouse

has been identifying and cataloging curriculum resources applicable

to

teaching activities revolving around 12 broad cultural themes organized

on a chart that provides

a –Spiral Pathway

for Integrating Rural Alaska Learning.” The themes that make up the S.P.I.R.A.L. framework are family, language/communication, cultural expression, tribe/community, health/wellness, living in place, outdoor survival, subsistence, ANCSA, applied technology, energy/ecology, and exploring horizons. These themes have also been used to formulate whole new curriculum frameworks that have been implemented in several schools and districts. The curriculum resources associated with each of these themes can be accessed through the ANKN web site.

Cultural Documentation/Atlas - Students in rural

schools are interviewing Elders in their communities and researching

available documents

related to the Indigenous knowledge systems associated with their

place, and then assembling the information they have gathered into

a multimedia format for publication as a –cultural atlas.” These

initiatives have focused on themes such as weather prediction,

edible and medicinal plants, geographic place names, flora and

fauna, moon and tides, celestial navigation, fisheries, subsistence

practices, food preservation, outdoor survival and the aurora.

(http://ankn.uaf.edu/NPE/oral.html)

Native Educator Associations - Associations of

Native educators have been formed in each cultural region to provide

an avenue for

sustaining the initiatives that are being implemented in the schools

by the AKRSI. The regional associations sponsor curriculum development

work, organize Academies of Elders and host regional and statewide

conferences as vehicles for disseminating the information that

is accumulated. A new statewide Alaska Native Education Association

has been formed to represent the regional associations at a statewide

level. (http://ankn.uaf.edu/NPE/ANEA/)

Native Ways of Knowing - Each cultural region has been engaged

in an effort to distill core teaching/learning processes from the

traditional forms

of cultural transmission and to develop pedagogical practices in

the schools that incorporate these processes (e.g., learning by

doing/experiential learning, guided practice, detailed observation,

intuitive analysis, cooperative/group learning, listening skills

and trial and error).

Academies of Elders - Native educators have been meeting with

Native Elders around a local theme and a deliberative process through

which the Elders

share their traditional knowledge and the Native educators seek

ways to apply that knowledge to teaching various components of

the curriculum. The teachers then field test the curriculum ideas

they have developed, bring that experience back to the Elders for

verification, and then prepare a final set of curriculum units

that are pulled together and shared with other educators.

Cultural Standards ® Alaska Native educators

have developed a set of –Alaska Standards for Culturally Responsive

Schools” that provide explicit guidelines for how students, teachers,

curriculum, schools and communities can integrate the local culture

and environment into the formal education process so that students

are able to achieve cultural well-being as a result of their schooling

experience. In addition, a series of additional –guidelines” have

been prepared around various issues to offer more explicit guidance

in defining what educators and communities need to know and be

able to do to effectively implement the Cultural Standards. (http://ankn.uaf.edu/publications/standards.html)

Village Science Curriculum Applications - Several volumes of village

oriented science and math curriculum resources, including a –Handbook

for Culturally Responsive Science Curriculum” (Stephens,

2000), have been developed in collaboration with rural teachers for use in schools

throughout Alaska. They serve as a supplement to existing curriculum materials

to provide teachers with ideas on how to relate the teaching of basic science

and math concepts to the surrounding environment.

Culturally-based Education and Academic Success are Compatible

In August, 2005, the Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative completed

its final year with a full complement of rural school reform initiatives

in place stimulating a reconstruction of the role and substance

of schooling in rural Alaska. Students

are now spending more time out in the community with

Elders, parents and local experts. School curricula are reflecting

the knowledge, values and practices

that have been a traditional part of life in the local

communities. Teachers are incorporating a more place-based pedagogy

that is engaging students in studies

associated with the surrounding physical and cultural

environment. The Alaska Standards for Culturally Responsive Schools

developed by Alaska Native educators

have been adopted by the State Board of Education side-by-side

with the state subject area standards and have become a part of

the lexicon of education in

schools throughout Alaska.

The beneficial academic effects of putting students in

touch with their own physical environment and cultural traditions

through guided experiences have not gone

unnoticed by school districts and other Native organizations

around the state. One AKRSI school district has urged all of its

schools to start the school year

with a minimum of one week in a camp setting, combining

cultural and academic learning with parents, Elders and teachers

all serving in instructional roles.

One school in the district has built in to their program

a series of camp experiences for the middle school students, with

a well-crafted curriculum addressing the

state content standards as well as the cultural standards.

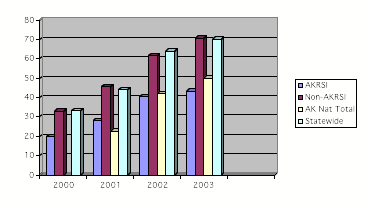

Given the accountability demands of No Child Left Behind, a central

question throughout all these educational

innovations has been, what impact do they have on student

academic achievement.

With the advent of the state standards-based Benchmark tests and

the High School Graduation Qualifying Exam in 2000, we now have

four

years of data on student performance in the 8th and 10th grade

math exams, from which we can make comparisons

between AKRSI-affiliated schools and non-AKRSI schools

for those two grade levels (AKRSI, 2004). Following are two graphs

showing the percentage of students performing

at the –advanced” or –proficient” levels on those exams.

EIGHTH GRADE MATHEMATICS BENCHMARKS ® 2000/2001/2002/2003

% Rural Students as Advanced/Proficient

TENTH GRADE MATHEMATICS HSGQE ® 2000/2001/2002/2003

% Rural Students as Advanced/Proficient

The most notable features of these data are the significant increases

in AKRSI student performance for both grade levels each year between

2000 and 2003. However, while the 8th grade AKRSI students showed

significant progress in closing the achievement gap with their

non-AKRSI counterparts from 20 to 17 percentage points, the 10th

grade students in both groups showed a substantial gain from 2000

to 2003, leaving the achievement gap largely intact at that grade

level.

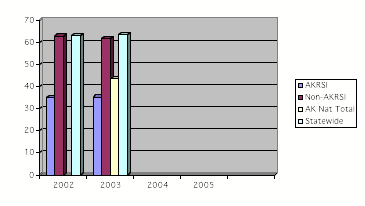

NINTH GRADE MATHEMATICS TERRA NOVA/CAT-6 ® 2002/2003

% Rural Students Scoring in Third and Fourth Quartiles

In addition to the state benchmark data, we also have norm-referenced

test results for 9th grade students who have been taking the Terra

Nova/CAT-6 since 2002. Though the differentials for each group

between 2002 and 2003 remain small, the AKRSI students do show

a slight increase in performance, while the non-AKRSI students

reflect a small decrease in their performance over the two years.

The consistent improvement in academic performance of students

in AKRSI-affiliated schools over each of the past four years leads

us to conclude that

the cumulative effect of utilizing the Alaska Standards for Culturally

Responsive Schools to increase the connections between what students

experience in school and what they experience outside school

appears to have a significant impact on their academic performance. Summary

The initiatives outlined above have demonstrated the viability

of introducing strategically placed innovations that can serve

as –catalysts” around which a new, self-organizing, integrated educational system can emerge which shows signs of producing the quality of learning opportunity that has eluded schools in Native communities for over a century. The substantial realignments that are already evident in the increased interest and involvement of Native people in education in rural communities throughout Alaska point to the efficacy of tapping into the cultural strengths of local communities in shaping reform in educational systems.

We are mindful of the responsibilities associated with taking

on long-standing, intractable problems that have plagued schools

in Indigenous settings throughout the world for most of the past

century, and we have made an effort to be cautious about raising

community expectations beyond what we can realistically expect

to accomplish. Our experience over the past ten years has been

such however, that we are confident in the route we chose to initiate

substantive reform in rural schools serving Alaskaês

Native communities, and while we have encountered plenty of problems

and challenges along the way, we have been able to capitalize on a broadly

supportive climate

to implement changes that have benefited not only rural schools

serving Native

students, but have been instructive for all schools and students.

We intend to continue to explore these ideas and find ways to strengthen the

connection

between

school and community in the educational systems serving all segments

of our

society. REFERENCES

[Most of the references cited in this article can be found on

the Alaska Native Knowledge Network web site at http://www.ankn.uaf.edu]

Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative

2004 Annual Report. Fairbanks: Alaska

Native

Knowledge Network (http://ankn.uaf.edu/arsi.html), University

of Alaska Fairbanks.

Barnhardt, Ray and A. Oscar Kawagley

2005 Indigenous Knowledge Systems

and Alaska Native Ways of Knowing. Anthropology and Education

Quarterly 36(1):

8-23. (http://ankn.uaf.edu/Curriculum/Articles/BarnhardtKawagley/Indigenous_Knowledge.html)

Barnhardt, Ray and A. Oscar Kawagley

2004 Culture, Chaos and Complexity:

Catalysts for Change in Indigenous Education. Cultural

Survival Quarterly 27(4): 59-64. (http://ankn.uaf.edu/Curriculum/Articles/BarnhardtKawagley/ccc.html)

Barnhardt, Ray and A. Oscar Kawagley

1999 Education Indigenous to Place:

Western Science Meets Indigenous Reality. In Ecological

Education in

Action. Gregory Smith and Dilafruz

Williams, eds.

Pp. 117-140. New York: State University

of

New York Press. (http://ankn.uaf.edu/Curriculum/Articles/BarnhardtKawagley/EIP.html)

Boyer, Paul

2005 Alaska: Rebuilding Native

Knowledge. In Building Community: Reforming Math and Science

Education in Rural Schools. Paul Boyer. Washington,

D.C.:

National Science Foundation.

Kawagley, A. Oscar

1995 A Yupiaq World View:

A Pathway to Ecology and Spirit. Prospect

Heights, IL: Waveland Press.

Napoleon, Harold

1991 Yuuyaraq: The Way of

the Human

Being. Fairbanks: Center for Cross-Cultural Studies,

University of Alaska

Fairbanks.

Stephens, Sidney

2000 Handbook for Culturally

Responsive Science Curriculum. Fairbanks: Alaska Native Knowledge

Network(http://ankn.uaf.edu/handbook/), University

of Alaska

Fairbanks.

|