Alaska Native in Traditional Times: A Cultural Profile

Project

as of July 2011

Do not quote or copy without permission from Mike

Gaffney or from Ray Barnhardt at

the Alaska Native Knowledge Network, University of Alaska-Fairbanks. For

an overview of the purpose and design of the Cultural Profile Project, see Instructional

Notes for Teachers.

Mike Gaffney

Chapter Four

Alaskan Environments and Native Adaptations

Climate – arctic, sub-arctic, maritime, seasonal changes

Physiography – physical features of the area – tundra, rivers, mountains,

valleys, ocean conditions (e.g., sea ice)

Flora – plant life

Fauna – land animals, sea mammals, water fowl, fish

Demographics – Size & distribution of population, settlement patterns

Land use – Mapping uses of lands & waters – location and boundaries,

community security

As shown above, this chapter gets you started on the Cultural Profile of your selected

Native group or groups. It provides you with an instructional guide for profiling elements of the

environment inhabited by your Native group(s) and their use and occupancy of land. These

elements are exactly the same as listed in the Cultural Profile Project Outline on page three. The

chapters to come on Social Organization, Worldview, and Cultural Products offer similar

instructional guidance for completing your project. You will find, however, that this and the

remaining chapters offer much more than a simple guide. As said before, we want to carefully

explain the concepts we use to organize our thinking about Native societies in traditional times.

What exactly do we mean, for example, when we use concepts like environmental adaptation or

land-use patterns or social stratification or governance or shamanism?

The Big Picture

South vs. North. Here we emphasize

the idea that elements of the environment set the parameters, the outer

limits, of what environmental adaptations were possible for subsistence-

based Native societies occupying a particular region. Again, the amount and

kind of subsistence and material resources available in the environment

largely determined what that Native society

looked like demographically, socially, and technologically. The Aleuts (Unagan),

for example, could do things within their maritime island environment that

Interior Athabaskans could not do

within their landlocked sub-Arctic environment. Of course interior Athabaskans

could do things that Aleuts could not.

Now let’s take a moment to paint the broadest possible picture of the

relationship between Alaska’s different environments and the social

organizations of Native groups

inhabiting these areas. Look at a map of Alaska which shows the Alaska Range.

Denali (Mt. McKinley) is the best known topographic feature of this mountain

range which stretches across

most of Alaska from east to west. Now draw or imagine a line along the top

of the Alaska range. South of that line – south of the Alaska Range – we

find very different environments and traditional Native social organizations

from what we find north of the Range. Note that the

Alaska Range does not extend into Southwest Alaska and the Central Yup’ik

homeland. Shortly we discuss this regional environment as a “transitional

zone.”

The South. Easy year-round access

to abundant marine resources in the oceans and rivers south of the

Alaska range supported larger Native populations. It is true that in important

ways the southern Alaskan

regional environments of the Aleut and the Tlingit are different. The

Aleuts lived mainly on barren, windswept islands and the Tlingit in areas

of high mountains, old growth forests, and sheltered bays and coves.

But the important point is that both of these very

different regional environments yielded a steady supply, even surpluses,

of subsistence marine resources.

Not only were southern Native populations

larger but their settlements were more densely populated and more permanent

than those found in the

north. By “densely populated” we mean a

large concentration of people within an given area. There are, for

example, many more people living within each square mile of New York

City than

people living within each square mile of

Fairbanks, Alaska. The southern settlements, moreover, were much more

permanent because they had easy access to their subsistence resources

throughout the year. Unlike many northern

Native societies, people were not forced to move with the seasons or

spend weeks on a hunting or fishing expedition just to meet the basic

dietary needs of their families. To say that their

primary subsistence resources lay just outside their front door is

not much of an exaggeration.

When added together, these factors — large,

permanent, densely populated settlements with abundant resources — led

to the development of a more elaborate social organization to regulate

tribal affairs. Certainly we will find more and larger government departments

and

neighborhood institutions such as churches and schools in New York

than in Fairbanks. Another prominent feature of the more complex southern

Native societies was their hierarchical social

structure. A hierarchical or ranked society exists when there is an

unequal

distribution of wealth, power, and social status among different classes

of people. When we ask about the structure and

distribution of wealth, power, and social status, we are asking about

a society’s social

stratification – its system of social ranking.

The social stratification of southern Native societies

was based on the hereditary ranking of families and clans. This meant that

the social

status of the family and clan into which a person

was born largely determined what social and economic advantages were

available to that person, both as a child and later as an adult. General

speaking,

these ranked societies consisted of an

aristocracy of clans at the top of the social pyramid, with commoners

occupying the middle and lower reaches of society. In all southern

Native

hierarchical

societies, the lowest social rank or

class was occupied by slaves obtained through war and trade.1 Among

the Tlingit, for example, the most basic social unit at the local level

was

the household group. It consisted of men of the

same matrilineal line and their families living together in very large

wooden plank-and-beam

houses Sometimes these “longhouses” were as large as 40 x

60 feet. (A full-size basketball court measures 50 x 84 feet). Figure

4-1 shows exterior and interior views of a Tlingit longhouse.

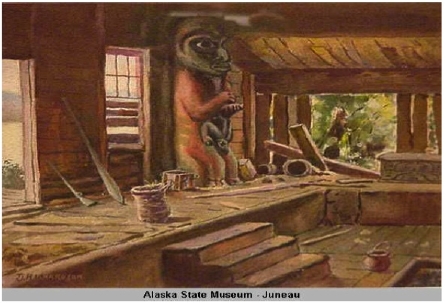

Figure 4-1

Men in ceremonial regalia in front of Klukwan clan house, c. 1880s

Winter and Pond Collection

Watercolor painting by Theodore Richardson, showing interior of Tlingit clan house

(no date)

Because of very accessible and abundant resources, not everyone had to be involved in

the daily round of subsistence activities. This meant that certain individuals possessing special

talents could devote a major portion of their day to work other than hunting, fishing, and

gathering. Consequently there arose occupational specialization in important areas such as

medicine, arts and crafts, spiritual leadership, political organization, and in the conduct of war

and commerce. If the knowledge and skills of a particularly talented person became highly

valued, he or she could concentrate time and energy on that specialty while their subsistence

needs were provided for by their household group or clan. They may even have received

payment for services from others within the larger community. Among the Tlingit, for example,

the elder head of a household group usually did not physically participate in subsistence activities.

He had instead a full time job as the political and ceremonial leader of the household and as their

chief historian and educator. If their skills were especially prized, individuals could gain wealth and

privilege ordinarily reserved for those of a higher hereditary rank. The possibility of upward social

mobility through demonstrated expertise in a valued specialty was certainly important to slaves. It

was one way they could rise above their wretched social rank and avoid a life of despair and the

possibility of being sacrificed at a potlatch. In a word, there existed a more elaborate division of labor

based on occupational specialization than we find in northern Native societies.

The North. With some exceptions,

the often marginal subsistence resources found north of the Alaska Range – particularly

for interior Athabaskans in Winter – meant small, highly

mobile Native populations spread over large areas. In contrast to the south,

there was far less permanence and density of settlements. The exceptions

were some Central Yup’ik areas around

Bristol Bay and in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta. In fact, the Central Yup’ik

region has been described as a transitional zone between north and south.

Without a substantial mountain range

to shield the region from southern exposure, it has environmental features

found in both the north and the south.2 Another

exception was the Point Hope region of Northwest Alaska in the early 1800s.

At that time the area’s subsistence resources, mainly marine mammals

and fish, sustained a large settlement area estimated at 1,000 people. 3

For

the most part, the social stratification of northern Native societies

was more egalitarian in structure. Unlike the social hierarchies of the

south, there was no easily identifiable

ranked social order where power and privilege differed significantly

among classes of people. Normally birth into a particular family was not

the

chief factor determining a person’s

opportunities in life and future adult social standing. The northern

societies offered a more level socio-economic playing field to all members

of the

group. Unlike the southern hierarchical

society, individual effort and merit were more likely to determine a

person’s

social status. The institution of slavery, moreover, did not exist north

of the Alaska Range.

Because everyone was always involved in some part

of the harvesting and preparation of subsistence foods and material products,

less time was available

to develop the kind of

occupational specialization that occurred in the south. This does not

mean there was no development of specialized skills and knowledge in

the north.

Every Native group had to

develop the necessary science and technology to successfully meet the

unique demands of their environments. We should not be surprised that

expertise

in weather forecasting and in animal

behavior are well developed areas of traditional Native science throughout

Alaska. Examples of Native technologies included the construction of

sea worthy hunting craft such as the kayak and

umiak, various hunting tools and weaponry, protective battle vests, weather

resistant housing, dog sleds and snowshoes. We will have a fuller discussion

of Native applied science and

technology when we discuss cultural products in Chapter

Eight.

Social stratification: beware of false

dichotomies. We

have said that social stratification refers to the structure of wealth,

power, and social rank in society. We have

discussed two seemingly opposite forms of traditional Native social stratification — the

southern hierarchical societies versus the northern egalitarian societies.

In so doing, however, we must be

careful not to create a false dichotomy by implying that these are two

quite separate and distinct

systems of social stratification. The word “dichotomy” means

the separation of a thing or idea into two opposite parts. A dichotomy

is an either-or proposition — it is either this thing

or that thing. It is either apples or oranges.

So what is the problem? The

problem is that there is no such thing as a purely hierarchical society

or purely egalitarian society, either in modern or traditional times. What

we have are human societies which are more – sometimes much more – hierarchical

than egalitarian and vice versa. And when we talk about the more or less

of things, we are talking about

variables. Variables are not absolute and permanent things. They are

constantly influenced by other factors and therefore always subject to

change. In the real world, social stratification is

very much a variable because any society can have a mix of hierarchical

and egalitarian elements. As much as its members may wish or claim, no

society is completely egalitarian. Some

form of social ranking is always present. Some individuals or families

or groups in society have more power and resources than others.

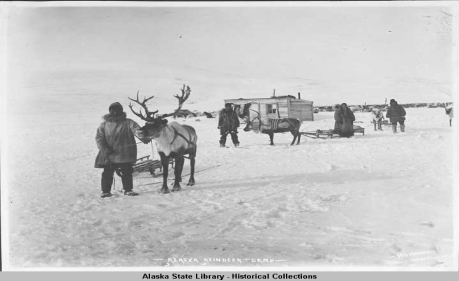

Figure 4-2

Alaska Reindeer Camp, c. 1913

In their study of reindeer herding and social change among the Iñupiaq of the northern

Seward Peninsula, the late Linda Ellanna and her co-author, George Sherrod, emphasize this

important social fact. Their study even includes a chapter entitled “The Myth of the Egalitarian

Society” in which they detail how wealth and power were never distributed evenly. Nor did these

Inupiat expect to live in a purely egalitarian community. There were always some who were

more clever and more ambitious than others. There were always some families who prospered

more than other families and passed these advantages on to later generations. Ellanna and

Sherrod make this interesting observation on control of vital subsistence technologies and key

hunting and fishing sites:

Technologies employed in collective harvesting endeavors included umiat

{skin boat], caribou surrounds, and fish weirs and nets. These items of technology

were not owned by the society nor owned equally by all segments of a large extended

local family. Instead, this technology was associated ... with the eldest productive

male of the group possessing the skills, knowledge, and wealth necessary to supervise

construction, maintenance, and use of these means of production. Additionally, this

individual and his closest kin controlled key geographic sites from which these

technologies were deployed.4

In the South, the occupational specialization

of the Tlingit and Haida hierarchical societies did allow for the egalitarian

element of upward social mobility. No matter the status of

one’s family or clan, an individual could achieve a higher social rank

based on demonstrated merit – on proven ability and accomplishment

in an occupation or skill valued by the society. Moreover, a society’s

social order can be changed by historic events such as internal revolts and

revolutions or by external forces such as invasion and occupation by a foreign

power. In 1886,

for example, a federal court ruled that the 13th amendment of the United

States Constitution prohibiting slavery also applied to Tlingit and other

Native groups regardless of what inherent

tribal sovereignty they may otherwise possess. Obviously this legal ruling

significantly changed Tlingit society by removing a major social and economic

stratum — slaves —from their

traditional hierarchical structure.5

So we must learn to think in terms of more or less hierarchy

or egalitarianism, not in terms of either – or ,

not in terms of either a completely hierarchical or a completely egalitarian

society. Some argue, for example, that despite its ideal values of equality

and the rule of law, the

social stratification of American society falls somewhere between hierarchical

and egalitarian because it has characteristics of both social structures.

Please understand that we use the

dichotomy of hierarchy versus egalitarian only as a starting point, only

as a framework for thinking about the different kinds of social stratification

that may exist. If you are doing a

cultural profile of a northern Native society, do not hesitate to look

hard

for elements of social ranking. Likewise, if you are researching a southern

Native society, look hard for elements of

egalitarianism such as social mobility – the ways individuals could

rise above or fall below the social rank of their birth.

A South – North summary. We can compose

a brief outline to summarize the contrast between the north and the south.

The symbol↓ means “results in”.

Southern Native societies (south

of the Alaska Range)

Abundant subsistence resources, even

to the point of producing surpluses

↓

Larger, more permanent and more densely settled Native communities

↓

Hierarchical societies with an uneven distribution of power and wealth, with

a more complex division of labor based on occupational specialization

Northern Native societies (north

of the Alaska Range)

With some exceptions, marginal, sometimes

scarce subsistence resources

↓

Smaller, more mobile and sparsely settled Native communities

↓

More egalitarian social organization with much less division of labor based

on occupational specialization.

Interior Athabaskans and Southern Athabaskans. In traditional times the only social

facts the Interior Athabaskan groups north of the Alaska Range had in common with the Tanaina

and Copper River Ahtna Athabaskans of the south was language and ethnicity. On the broad

cultural profile factors of regional environment, land use and occupancy, and social organization,

Tanaina and Copper River Ahtna life more closely resembled the other southern Native societies.

In the North, the life of the Interior Athabaskans more closely resembled other northern Native

societies.

Special features of the regional environment. Some features of the regional

environment may require special attention. These are features which “set up” the significance of

certain elements of Social Organization and Cultural products later in your Cultural Profile. The

fauna [animal life] of any Native group’s region is probably the most obvious set-up element

because people’s lives were almost totally organized around hunting and fishing. A clear

description of the area’s fish and game resources therefore sets up what you later say about how

the group organized its seasonal rounds of hunting, fishing and gathering, and what weapons and

other materials were necessary for success.

But there may be other set up features also requiring

special attention. If you choose to profile the coastal Iñupiaq, for example, you will describe the usual physiographic features of

mountains, valleys, and rivers. Of course you will do this for whatever Native group you are

profiling. But for the coastal Iñupiaq, an equally significant but often overlooked feature of their

environment is sea ice. Think about the relationship between sea

ice and Iñupiaq life. Does not

much of the coastal Iñupiaq subsistence activities – from seal hunting to whaling – depend on sea

ice conditions? If so, then the social and technological adaptations made by the Iñupiaq to

different sea ice conditions were absolutely crucial for establishing a way of life that went

beyond mere survival. Therefore a more detailed picture of sea ice and its seasonal changes is

necessary to set up your later descriptions of coastal Iñupiaq social organization and cultural

products.

Environmental adaptation. Obviously a Native group had to have the right hunting and

fishing technologies to effectively adapt to a particular environment. What may not be so

obvious is that Native groups first had to socially organize themselves in ways that a) maintained

the most effective member participation in harvesting of subsistence resources, and b) most

effectively distributed these resources among its members according to the values and traditions

of the group. Note that already we are discussing different ways Native societies were organized.

Even with the social organization part of the Cultural Profile still several chapters away, we are

already using terms like social stratification, hierarchical societies, egalitarian societies. Why?

Because significant features of social life in traditional times were shaped by the nature of the

environment. It was imperative that Native groups socially organized themselves in ways that

took best advantage of the opportunities of their environment while avoiding the dangers.

Environmental Adaptation is the concept which ties all these elements together. In a moment we

will add a final piece to this organizing concept.

Use and Occupancy of Land

Note: “Occupancy” as used in federal Indian law means the same thing as

the more familiar term “settlement patterns”.

Here we want to know the demographics of our selected

Native group in traditional times. We need some idea of the number of people

living in their tribal homeland at the time of

the invasions. But do not stop with just researching population size – with

just the estimated number of people living within the group’s territory.

Equally important for getting a good picture of what life was like back

in those days is understanding the distribution of people across

your Native group’s territory. This information gives us a picture

of their settlement pattern. Did people occupy more densely populated settlements

like the Tlingits? Or like the Iñupiaq, was

their traditional territory dotted with smaller settlements of various sizes?

Or like Interior Athabaskans with their still smaller and widely distributed

population, did family and local band

units regularly move from one hunting area to another, particularly during

winter months? Right away we see that maps are crucial if we are to construct

a complete picture of Native settlements

and land use in traditional times.

As we should expect, Native communities in traditional

times had to establish their settlements close by fresh water and with the

best possible access

to fish and game. Often these

settlements were in places sheltered from violent weather. Yet many of

these communities still had another factor to consider before settling down – what

location offered the best physical security against potential enemies? For

an example, let’s go to the Aleutians and the research of

Waldemar Jochelson, a Russian anthropologist who did fieldwork among the

Aleuts in the early 1900s. Reporting on the factors determining the location

of Aleut villages, he says:

All the ancient Aleut villages were situated on the sea-shore, not on the high land

above the sea, and usually on land between two bays, so that their skin boats could easily be

carried from one body of water to another at the approach of foes. Thus the usual location of

villages was on narrow isthmuses, on necks of land between two ridges, on promontories, or

narrow sandbanks. An indispensable adjunct to a village was a supply of easily accessible

fresh water – a brook, fall, or lake. River-mouths were never used as permanent dwelling

places, because the topographical conditions were conducive to unexpected attacks. The

underground dwellings of the old Aleut [Aleuts of traditional times]were much like traps; if

an attack were made when the inhabitants were within, they could leave it alive only

through a single opening in the roof. For this reason villages were built on open places,

whence observations could be made far out to sea. Nearly every village had an observatory

on a hill where constant watch was kept... 6

Be sure to look for similar kinds of information on problems of community

security and how it was a factor in determining settlement patterns for your selected

Native group.

Environmental adaptation: a final definition. Now we can complete our definition of

environmental adaptation. The Aleut example of defensive positioning as a factor in village

location makes it clear that we need to include the social world as well as the natural world in

any definition of Alaska Native environmental adaptation. Unless truly isolated over long

periods of time, any social group will have some relationship with other groups. As with

individuals, all human groups must adapt to the larger social environment in which they live. At

any given time this environment can include both friendly and hostile forces. Every Native group

conducted some form of foreign relations and provided for its own defense. Warfare, commerce,

and alliance-building falls within the general meaning of foreign relations. So we need a

definition of environmental adaptation which includes the social as well as the natural

environment. Accordingly, our final and complete definition is:

Environmental adaptation occurred when a Native society socially organized

itself and developed technologies to a) effectively live in and harvest the material

and subsistence resources of its regional environment, and b) to effectively

established secure and beneficial relations with other Native groups within their

larger social environment.

Land use and aboriginal title

“�Its not down on any map; true places never

are.

” – Herman Melville, Moby Dick

Tlingit and Haida Indians of Alaska v. the United States. This historic Indian law case

began way back in 1929 when the Alaska Native Brotherhood (ANB) petitioned Congress to

waive the sovereign immunity of the United States so that ANB could sue the federal

government for not protecting their aboriginal title to lands in Southeast Alaska. In 1935,

Congress agreed with ANB’s aboriginal title argument and said these tribes should have their

day in court. Congress then passed what is known as a “jurisdictional act” authorizing the federal

Court of Claims to begin investigating the Tlingit and Haida complaint according to certain

congressional guidelines. When passing a jurisdictional act, the United States government

consents to being sued, thus waiving its sovereign immunity for that purpose only. Sovereign immunity is a legal principle passed down from old English law proclaiming that “a king can do

no wrong.” The principle has since been restated to say that one cannot sue the sovereign without

the sovereign’s consent. The reasoning is that “sovereignty” would have little meaning if the

sovereign does not have complete legal protection – that is, “immunity” – against all claims that

might be made against it, whether by its own citizens or by foreign powers. If everyone having a

disagreement with governing authorities can sue the state, then the state is without the necessary

power to effectively rule. In the case of the Tlingit and Haida, what followed were years of delay

and much investigation by the Indian Claims Commission, the only judicial body ever

established for the sole purpose of hearing Native American complaints against the federal

government and recommending compensation or other forms of restitution.

We know that in 1959 – also the year of Alaska statehood – the Court of Claims ruled in

the Tlingit and Haida case that the federal government had indeed violated the aboriginal title of

these Southeast Alaska tribes. Therefore these tribes had a right to financial compensation for

lands illegally taken from them. Clearly it set the stage for ANCSA by establishing aboriginal

title in Alaska as valid legal doctrine. Now all Alaska Natives had a persuasive legal argument to

support their land claims petition in Congress. But unlike Native regions and villages under

ANCSA, the Tlingit and Haida retained no land in 1959. It was a landless settlement. They

received instead financial compensation for lands illegally taken from them over the years. Later,

however, Tlingit and Haida villages would recover parcels of land through ANCSA.

Expanding the definition of Aboriginal

Title. To

prove use and occupancy usually means drawing maps based on the tribe’s

oral history of the area, on the written accounts of early visitors to the

tribe’s territory, and on other available social and scientific information.

Mapping the proof of actual occupancy (the location of Native settlements)

has not presented much of a

problem. On the other hand, mapping proof of all the territory used by

a Native group for subsistence hunting and fishing has resulted in major

land claims controversies, not only in

Alaska but also in the Lower-48 and in Canada.

Now let’s suppose that during a court hearing

on a Native land claim, lawyers for the federal government make the following

argument: Okay,

we acknowledge these specific areas of

the map accurately show where Native people actually resided in traditional

times. And we agree that the tribe should be compensated for the loss

of this and the immediately surrounding land.

But we do not acknowledge the much larger territory they claim to have

used for their yearly round of subsistence activities. We understand

that aboriginal title means both use and

occupancy, but we see no good evidence that the tribe regularly did

subsistence on all of the lands claimed by them. In fact, we don’t

see how they can make such an extensive claim since the area includes steep,

rocky, and barren lands on which no subsistence hunting and fishing

could have taken place.

In fact, the federal government actually put forth

such a “barren

lands” argument in the

Tlingit and Haida case. They asserted that some of the claimed lands,

particularly along the mountainous boundaries to the east, were inaccessible

or useless and should not be included in

any claim based on aboriginal title. The Tlingit and Haida had claimed

aboriginal title to virtually all lands of southeast Alaska, from Klukwan

in the north to Annette Island in the south.

To the west they claimed all islands of the Southeast Archipelago as

well as all of the mainland including the western slopes of the great

mountain ranges to the east. The Court of Claims

responded to the federal government’s argument by asking two questions:

a) did Alaska tribes in fact use and occupy the lands they claimed?

And b) if some of the claimed lands were “barren,

inaccessible, and useless,” did the tribes still exercise dominion

over these lands? Let’s have the

Court speak for itself on this question:

We do not mean to depart in any sense from the rule of long standing that Native

title to lands must be shown by proof of actual use and occupancy from time

immemorial. But it is obvious from a study of the many cases involving proof of Native

title to lands both in this court and at the Native Claims Commission where the Indians

have proved that they used and occupied a definable area of land, the barren,

inaccessible or useless areas encompassed within such overall tract and

controlled and dominated by the owners of that surrounding land, as well as the barren mountain peaks

recognized by all as the borders of the area of land, have not been

eliminated from the areas of total ownership but rather have been assigned

no value in the making of an

award, if any, to the Indians. [Emphases ours]

We have emphasized those parts of the opinion where the Court of Claims expanded the

definition of aboriginal title beyond use and occupancy. It now included lands over which tribes

were traditionally recognized as having dominion, even if not regularly use and occupied by

tribal members. Once this part of the case was concluded and full aboriginal land title had been

established, a second hearing took place. At this hearing the court calculated the compensation

the federal government owed the tribe by determining the value of the land at the time it was

illegally taken. It was during the second hearing that the “barren and inaccessible” lands already

ruled as part of the tribe’s aboriginal title were subtracted from the total compensation amount.

Why? Because they are judged not to have had material value. In 1965, after all the maps were

studied and all the financial calculations were done, the Tlingit and Haida received $7.2 million

compensation for lands taken from them. (Here is an interesting historical note: The United

States purchased Russia’s colonial interests in all of Native Alaska for the same amount, $7.2

million.)

So far we have learned that:

- Aboriginal title is a fundamental principle of federal Indian

law.

- Proving a tribe’s historic occupancy (settlement pattern) of

land has been much easier than proving their use of lands and waters

which could stretch far

beyond the actual settled areas.

- Although not compensated for,

the barren, unusable lands traditionally under a tribe’s dominion

are considered part of their aboriginal title.

- Whether in the Tlingit

and Haida case or in ANCSA, Native land claims based on aboriginal

title should closely match their actual

land use patterns in

traditional times.

ANCSA and mapping land use. You

are required to describe how your selected Native group traditionally used

and occupied their lands and waters. Certainly a complete description

requires mapping their territorial boundaries and settlement pattern. This

mapping exercise raises three interesting questions you should consider

researching.

First, does your map of traditional land-use correspond to the lands your

Native group or groups actually claimed by right of aboriginal title? One

place to begin your investigation is with

a 1968 study conducted by the Federal Field Committee on Development Planning

in Alaska. In order to have reliable information for judging various Native

land claims, the Senate Committee

on Interior and Insular Affairs asked the Field Committee to undertake a

comprehensive research project. Among other things, the Field Committee

researched Native patterns of settlement and

land use in traditional times. The Committee’s findings were compiled

in a major document entitled Alaska Natives and the Land published

early in 1969. Their research clearly indicates that the Native claims to

most Alaska lands based on aboriginal use and occupancy were valid.7

The second interesting question is: To what extent

does your map or the maps in Alaska

Natives and the Land correspond to a map of ANCSA lands your Native

group actually retained in 1971? Do the boundaries lines match? Did your

Native group retain more land or less land or

about the same amount of land they originally claimed? The Native corporations

in your region should have this information. They may even have the maps

you need. In fact, the Field

Committee suggested that a fair settlement would be for Alaska Natives

to retain 60 million acres. But as we know, the final settlement had Natives

retaining only 44 million acres.

And thirdly, there is the ongoing issue of whether

Natives have some sort of aboriginal title to hunting and fishing rights

on the Outer Continental

Shelf (OCS) beyond Alaska’s three

mile jurisdiction. These are federal waters and the courts could decide

that ANCSA extinguishment of aboriginal title only applied to Alaska state

lands and waters.8 If you are

profiling a coastal Native group, two further research questions arise:

Did they hunt and fish beyond the three mile limit? If so, can a map be

drawn showing the area of the OCS where this

subsistence activity took place in traditional times?

Review Questions.

Can you define environmental adaptation and explain how this process

works?

Can you explain the major differences between Northern Native

societies and Southern Native societies and the way different

environments shaped the nature of these societies?

Why do we say beware of false dichotomies when studying Alaska

Native societies?

Why have we been forced to look at aspects of traditional Native social

life even before we get to the chapter on Social Organization?

Why is it important to add a social dimension to our definition of

environmental adaptation?

Why is it easier to prove traditional settlement patterns than

traditional land use?

How did the Court of Claims expand the definition of aboriginal

title in the Tlingit and Haida case?

Some Alaska Native tribes may still have a claim of aboriginal

title on the Outer Continental Self. Explain.

ENDNOTES

-

The basic framework for illustrating differences between

northern and southern Alaska Native societies is found in Joan Townsend’s “Ranked

Societies of the Alaskan Pacific Rim,” Senri Ethnological Studies,4,

1979, pp 123–156.

-

Alaska Natives and the Land, Robert Arnold et

al., Federal Field Committee for Development Planning in Alaska (Anchorage,

1968).

Online at: http://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED055719.pdf

-

Burch Jr., Ernest, The Traditional Eskimo

Hunters of Point Hope, Alaska, 1800–1875. Barrow, Alaska:

The North Slope Borough, 1981

-

Ellanna, Linda J. and Sherrod,

George K., From Hunters to Herders:The Transformation

of Earth, Society, and Heaven Among the

Iñupiaq of Beringia, Department of Anthropology, University

of Alaska – Fairbanks, August, 2004, p. 135.

-

In re Sah

Quah, 1 Alaska. Fed. Rpts. 136 (1886).

-

Margaret Lantis,

(Ed.), Ethnohistory in Southwestern and the Southern

Yukon: Method and Content. The University Press of Kentucky,

1970, pp. 179-180.

-

Alaska Natives and the Land, Chapter 3, “Land

and Ethnic Relationships.” (See the bibliographic reference

for a full citation and the document’s online location.)

-

See: David Case and David Voluck, Alaska Natives and

American Laws (Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Press, 2002) pp.

306-307 .

Table of Contents | Chapter

5

The

University of Alaska Fairbanks is an Affirmative

Action/Equal Opportunity employer, educational

institution, and provider is a part of the University of Alaska

system. Learn more about UA's notice of nondiscrimination. The

University of Alaska Fairbanks is an Affirmative

Action/Equal Opportunity employer, educational

institution, and provider is a part of the University of Alaska

system. Learn more about UA's notice of nondiscrimination.

Alaska Native Knowledge

Network

University of Alaska Fairbanks

PO Box 756730

Fairbanks AK 99775-6730

Phone (907) 474.1902

Fax (907) 474.1957 |

Questions or comments?

Contact ANKN |

|

Last

modified

July 6, 2011

|

|