FNSBSD Alaska Native Education

(DRAFT)

APPENDIX B

|

the

CARIBOU

in Alaska click on image for a bigger graphic |

|

Alaska Department of Fish and Game

Wildlife Notebook Series

THE CARIBOU (Rangifer tarandus) is

generally associated with the arctic tundra, mountain tundra and

northern forests of North America, Russia and Scandinavia. This

species has been a distinctive part of the Alaskan fauna for

thousands of years and is resident throughout the state except for

the Southeastern Panhandle and most offshore islands.

In Europe caribou are called reindeer, but in Alaska and Canada

only the domestic forms are known by that name. All caribou and

reindeer throughout the world are considered to represent a single

species. Alaska has only the barren-ground subspecies, but east of

the Rocky Mountains, in Canada, barren-ground and woodland caribou

may be found. The barren-ground caribou generally inhabits open

tundra lands near or above timberline while the woodland caribou

prefers the forested lands of southern Canada.

GENERAL DESCRIPTION: Caribou are large, rather stout deer with

large, concave hoofs that spread widely to support the animal in snow

and soft tundra and function well as paddles when it swims. Caribou

are the only members of the deer family in which both sexes grow

antlers. Antlers of adult bulls are large and massive; those of adult

cows are much shorter and are usually more slender and irregular. In

late fall caribou are clove-brown with a white neck, rump and feet

and often have a white flank stripe. The hair of newborn calves is

generally reddish-brown but may range from pale beige to dark brown.

Newborn calves weigh approximately 13 pounds and may double their

weight in 10-15 days. Adult bulls weigh 350-400 pounds. However,

weights of 700 pounds have been recorded in the Aleutian Islands.

Mature females average 175-225 pounds.

LIFE HISTORY: After a summer of grazing on succulent vegetation,

caribou enter the fall in prime condition and mature bulls frequently

have more than three inches of fat on the back and rump. The shedding

of velvet in late August and early September by large bulls marks the

approach of the rutting season. The bulls cease feeding and show

increasing aggressiveness that soon results in combat. Fights between

bulls are seldom violent and injuries are uncommon. The peak of the

breeding period in Alaska varies somewhat between herds, but most

mating occurs in October. Most yearlings are capable of breeding, but

the first breeding usually occurs at an age of 28-29 months. By late

October adult males have exhausted their summer accumulation of fat

and once again begin feeding. Bulls start to shed their antlers after

the rut and most adult males are "bald" by January. Pregnant cows and

young animals retain their antlers until May or June, but

non-pregnant females usually shed their antlers in April.

As the spring migration begins, females and many calves of the

previous year congregate as they move to the calving area. In late

May or early June a single calf is born. Newborn calves can walk

within an hour and after a few days can outrun a man and swim across

lakes and rivers.

FOOD HABITS: Like most herd animals, the caribou must keep moving

to find adequate food. This distributes feeding pressure and tends to

prevent overgrazing. Caribou are not as likely to starve to death as

moose or deer because if food is not available in one area, they move

to another.

In summer, caribou eat a wide variety of plants, apparently

favoring the leaves of willow and dwarf birch, grasses, sedges and

succulent plants. As autumn frost kills off plants and foliage, they

switch to lichens ("reindeer moss") and dried sedges. After a winter

of lichens and dried food, caribou seek out the first new growth of

spring.

MOVEMENTS: The Alaskan caribou is largely a mountain animal,

associated with areas above or near timberline, but its movements are

extensive and unpredictable. Areas known for many years to have great

numbers may suddenly be abandoned as the herd changes its migration

pattern. Such irregularities even today cause privation among the

native people in Alaska and Canada who depend upon caribou for food.

Annual caribou migrations are directional, long distance treks

occurring in spring and early summer as cows and young move to

traditional calving grounds and then to summering areas. The bulls

and some young animals follow far to the rear and scatter widely

during the summer. In midsummer, caribou are often harassed by hordes

of mosquitoes, warble flies and nose flies. Sometimes the animals

will run in a frenzy for long distances, stopping to rest only when

exhausted or when wind offers relief from the insects. In the fall

and early winter, the herd assembles for the rut and then moves to

wintering grounds.

POPULATION DYNAMICS: There are more than 400,000 wild caribou in

Alaska distributed in 13 more or less distinct herds. At present most

herds are healthy and increasing steadily, but the future can only

bring a decrease in numbers. As civilization encroaches and the back

country is developed, more and more valuable caribou habitat will be

lost.

HUNTING: The adult bull caribou is one of the most unique and

impressive trophy animals in the North. Each year several thousand

nonresident hunters travel to Alaska in search of these nomads.

However, the caribou's greatest value has been as a food animal and

more than 10,000 caribou are harvested each year by Indian and Eskimo

hunters. For many native Alaskans, the caribou is still an essential

source of food.

James E. Hemming

1970

click on image for a bigger graphic

|

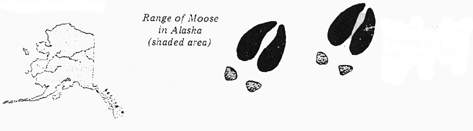

the

MOOSE

in Alaska

click on image for a bigger graphic

|

|

Alaska Department of Fish and Game

Wildlife Notebook Series

THE MOOSE (Alces alces) is

the

largest member of the deer family in the world and the Alaska race

(Alces alces gigas) is the largest of all the moose. Moose are

generally associated with northern forests in North America, Europe

and Russia. In Europe they are called "elk." In Alaska, they occur in

suitable habitat from the Stikine River in the Panhandle to the

Colville River on the arctic slope. They're most abundant in the

second growth birch forests, timberline plateaus and along the major

rivers of South-central and Interior Alaska.

GENERAL DESCRIPTION: Moose are improbable-appearing mammals:

long-legged in the extreme, short-bodied, with a stupendous drooping

nose, a useless "bell" or dewlap under the chin, no apparent tail,

colored a variety of brindle browns, shading from pale yellow to

almost black, depending upon the season and the age of the animal.

The hair of newborn calves is generally orange-brown fading to a

lighter rust color within a few weeks. Newborn calves weigh 28 to 35

pounds and grow to over 300 pounds within five months. The few adult

males in prime condition that have been weighed indicate that 1.000

to 1,600 pounds is the usual range; adult females weigh 800 to 1,200

pounds. Only the bulls have antlers. The largest moose antlers in

North America come from Alaska. In Alaska, trophy class bulls are

found throughout the state, but the largest come from the Alaska

Peninsula, lower Susitna Valley and Kenai Peninsula. Moose produce

trophy-size antlers when they are six or seven years old, and may

continue to produce large antlers until they are 13 or 14. In the

wild, moose may live slightly more than 20 years.

LIFE HISTORY: Moose breed in the fall, with the peak of "rut" activities

coming in late September and early October. Cow moose generally first breed

when 16 or 28 months old. They mature at 16

months on good, uncrowded range. Calves are born in late May or early

June after a gestation period of about 240 days. Older cows have

twins 15 to 60 per cent of the time and triplets may occur once in

every 1,000 births. The incidence of twinning is also related to

range conditions. On good range more cows have twins. Most calves are

born in swampy muskeg areas. A cow moose defends her newborn calf

vigorously.

Calves begin taking solid food a few days after birth and

are

weaned in the fall, at the time the mother is breeding again. The

maternal bond is not ruptured until the calves are 12 months old when

the mother forcibly ejects the 400-pound "baby" from her "parturition

pasture" just before she gives birth. Actually, calves three months

old get along fine without their mothers as several transplant herds

have been started with calves released at that age.

Adult males joust during the rut by placing their antlers together

and pushing. The winner takes the female and both bulls may receive a

few punctures or other damage.

By late October adult males have exhausted their summer

accumulation of fat and their desire for feminine company and once

again begin feeding. Antlers are shed in November, December and

January --the majority in late November and early December.

FOOD HABITS: During fall and winter moose consume prodigious

quantities of willow, birch and aspen, and in some areas actually

establish a "hedge" or browse line six to eight feet above the ground

by clipping all the terminal shoots of favored food species. Spring

is the time of grazing, and moose utilize a variety of foodstuffs,

particularly sedges, equisetum (horsetail), pond weeds and grasses.

In some areas they feed on vegetation in shallow ponds all summer. In

other situations forbs and leaves of birch, willow, alder and aspen

are the main summer diet.

MOVEMENTS: Moose are often thought of as sedentary animals. They

may be, but definite seasonal movements, associated with breeding,

parturition and treks to favored forage areas, may cover 20 to 40

miles. A tagged moose is known to have moved 60 miles.

In mountainous areas bulls spend most of the summer and

early fall at or above timberline while cows with calves prefer more dense

cover

at lower elevations. During the "rut" cows move toward timberline and

the bulls meet them halfway. Following the rut, the sexes separate

and groups of 10-20 bulls at or above timberline are not uncommon.

POPULATION DYNAMICS: Moose have a high reproductive potential and

quickly fill a range to capacity. Mother Nature in effect determines

how many moose will persist on a given unit of land. Deep crusted

snow, when combined with tired, overutilized range, can lead to

malnutrition and subsequent death of hundreds of moose and greatly

decrease the survival of the succeeding year's calves.

Moose are eaten by wolves, the only effective predator on adult

moose, and brown bears. Black bears take some calf moose in May and

June. Several parasites may be important population controls when

moose become very abundant.

HUNTING: More people hunt moose than any other of Alaska's big

game species. To many people the best hunting is during September

when the trees and shrubs are in full fall color and just being

outdoors in Alaska is, in itself, a sufficient trophy.

ECONOMIC AND FUTURE STATUS: Because moose range over so much of

Alaska, they have played an important role in the development of the

state. Market hunting was once a way of life for professional hunters

supplying moose meat to mining camps. Historically, moose were an

important source of food, clothing and implements to Athabascan

Indians dwelling along the major rivers. Today some 35,000 Alaskans

and nonresidents annually harvest 9,000 to 10,000 moose --some five

million pounds of meat --from a total population estimated at 130,000

to 160,000. Moose are an important part of the Alaskan landscape and

thousands of tourists annually photograph those animals that feed

contentedly along the highways.

Man's developments in Alaska include many alterations upon the

face of the land. These activities create conflicts between man and

moose, as moose eat crops, stand on airfields, eat young trees,

wander city streets and collide with cars and trains.

Man's removal of mature timber through logging and careless use of

fire has in general been beneficent to moose as new stands of young

timber have created vast areas of high quality moose food. The future

is reasonably bright if man learns to manipulate habitat and does not

overprotect moose so that they can ruin their future food supply.

Robert A. Rausch

Revised and reprinted 1978

click on image for a bigger graphic

|

the

DALL SHEEP

in Alaska

click on image for a bigger graphic |

|

Alaska Department of Fish and Game

Wildlife Notebook Series

DALL SHEEP, Ovis dalli dalli,

inhabit the mountain ranges of Alaska. Dall sheep are found in

relatively dry country and frequent a special combination of open

alpine ridges, meadows, and steep slopes with extremely rugged "escape terrain" in

the immediate vicinity. They use the ridges, meadows, and steep slopes for feeding

and resting. When danger

approaches they flee to the rocks and crags to elude pursuers. They

are high country animals and are seldom found below timberline in

Alaska.

Male Dall sheep are called rams; they have massive curling

horns.

The females are called ewes and have shorter, more slender, slightly

curved horns. Rams resemble ewes until they are about three years

old, after that continued horn growth makes them easily recognizable.

Horns grow steadily during spring, summer, and early fall. In late

fall or winter horn growth slows and eventually ceases, probably

because of changes in body chemistry during the rut, or breeding

season. This yearly stopping of horn growth results in a pattern of

rings or annuli spaced along the length of the horn. These annual

rings can be distinguished from other rough corrugations on the

sheep's horns, and a sheep's age can be accurately determined by

counting these horn rings or annuli (see sketch). Dall rams as old as

16 years have been killed by hunters, and ewes have been known to

reach the age of 19 years, but usually a 12 year-old sheep is

con-sidered very old. As rams mature their horns form a circle when

seen from the side. Ram horns reach half a circle in about two or

three years, 3/4 of a circle in four to five years, and a full circle

or "curl" in seven to eight years.

LIFE HISTORY: The young, called lambs, are born in late May or

early June. As lambing approaches, ewes seek solitude and protection

from predators in the most rugged cliffs available on their spring

ranges. Ewes bear a single lamb, and the ewe-lamb pairs remain in the

lambing cliffs a few days until the lambs are strong enough to

travel. Lambs begin feeding on vegetation within a week after birth

and are usually weaned by October. Normally, ewes have their first

lamb at age three and produce a lamb annually. In stressed

populations, ewes frequently begin lambing on their second birthday

and then produce lambs in alternate years. More will be learned about

this difference as research continues.

Sheep have well developed social systems. Adult rams live in bands

which associate with ewe groups only during the mating season in late

November and early December. The horn clashing for which rams are so

well known does not result from fights over possession of ewes, but

is a means of establishing social order. These clashes occur

throughout the year (and also among females) on an occasional basis.

They occur more frequently just before the rut when rams are moving

among the ewes and meeting rams from groups other than their own.

Dall rams can sire offspring at 18 months of age, but normally they

do not participate in breeding or social activities until they

approach dominance rank (at full curl age and size).

FOOD HABITS: The diet of Dall sheep vary from range to range, but

they feed primarily on grasses and sedges. Dur-ing summer, food is

abundant, and a wide variety of plants are consumed. Winter diet is

much more limited and con-sists primarily of dry, frozen grass and

sedge stems available when snow is blown off the winter ranges. Some

popula-tions use significant amounts of lichen and moss during

winter. Most Dall sheep populations visit mineral licks during the

spring and often travel many miles to eat the soil at these unusual

geological formations. Soil eating may be caused by a mineral

deficiency or imbalance that results from the poor quality of winter

food. As several different popula-tions meet at mineral licks, ram

and ewe populations mingle and young rams join the ram band which

happens to be present at the time. This random contribution of young

rams to different ram bands benefits the sheep by maintaining genetic

diversity. Sheep are very loyal to their home ranges; after joining a

social group, sheep are never known to leave it. Mineral licks are

good spots to observe sheep because the animals are so intent on

eating the dirt they pay little attention to humans. However, major

disturbances such as low-flying aircraft or operating machinery

readily drive sheep from the mineral licks.

POPULATIONS:Dall sheep in Alaska are generally in good population

health. The remoteness of their habitat and its unsuitability for

human use protected Dall sheep from most problems in the past.

However, increasing human population and more human use of alpine

areas may cause future problems for Dall sheep. Mountain sheep in

general are extremely susceptible to diseases introduced by domestic

livestock.

If grazing of domestic sheep (or possibly cattle) occurs on their

ranges, mass die-offs from disease can be reasonably expected,

Currently, biologists believe the number of Dall sheep in Alaska is

about 70,000. Thirty thousand of these live in the Brooks Range,

15,000 in the Alaska Range, 16,000 in the Wrangell Mountains, 5,000

on the Kenai Penin-sula and the Chugach Mountains with which it is

connected, and 3,000 in the Talkeetna Mountains. The ancestral

habitat for Dall sheep, the Tanana-Yukon uplands, now contains an

estimated 1,000 Dall sheep.

Sheep typically exist at stable population levels in approximate

equilibrium with their habitat resources. Large popula-tion

fluctuations do occur, however, usually as a result of infrequent

catastrophic weather events. These events are more likely in maritime

climates, and history indicates they can be expected once in about

every 50 years. Low birth rates, predations, primarily by wolves,

coyotes, and eagles, and a difficult environment tend to keep Dall

sheep population growth rates lower than for many other big game

species. However, their adaptation to the unchanging alpine

environment seems to serve them well. They have survived for

thousands of years and are among the more suc-cessful animal groups.

HUNTING: Dall sheep produce excellent meat but are relatively

small in size (usually less than 300 pounds for rams and 150 pounds

for ewes) and it is difficult to retrieve meat from the rugged alpine

areas which they inhabit. These factors have limited sheep hunting to

a relatively few, hardy individuals whose interest is more in the

challenges and satisfactions of mountain hunting and the alpine

experience than in getting food. In some communities of the Brooks

Range, Dall sheep are hunted for subsistence. These hunts commonly

take place during winter when snow machine travel makes it easier to

reach the sheep and retrieve the meat. Recreational hunting is

limited to the taking of mature rams during August and September;

subsistence regulations commonly allow taking of all sex and age

classes of sheep. Population which support subsistence hunting must

be closely watched to assure that populations are not overex-ploited.

Many recreational hunters are very selective and choose not to kill a

ram unless it is unusually attractive, choosing to watch sheep and

share their environment instead. Likewise, viewers and photographers

of Dall sheep are attracted by the animals and their environment.

Photography of Dall sheep is popular for many visitors and residents

of Alaska and is not limited by season.

Wayne E. Heimer

1984

click on image for a bigger graphic

|

the

BLACK BEAR

in Alaska

click on image for a bigger graphic |

|

Alaska Department of Fish and Game

Wildlife Notebook Series

BLACK BEARS, Ursus americanus, are

the most abundant and widely distributed of the three species of

bears in America and have been recorded in all states except Hawaii.

In Alaska, blacks occur over most of the forested areas of the State.

They are not found on the Seward Peninsula or north of the Brooks

Range. They also are absent from some of the large islands of the

Gulf of Alaska, notably Kodiak, Montague, Hinchinbrook and others,

and from the Alaska Peninsula beyond the area of Lake Iliamna. In

Southeastern Alaska, black bears occupy most islands with the

exception of Admiralty, Baranof, Chichagof and Kruzof. These are

inhabited by brown bears. Both species occur on the Southeastern

mainland. They are most often associated with forests, but depending

on the season of the year, they may be found from sea level to alpine

areas.

GENERAL DESCRIPTION: The black is the smallest of the North

American bears. Adult bears stand about 26 inches at the shoulders

and measure about 60 inches from nose to tail. The tail is about two

inches long. Males are usually larger than females. An "average" adult male in

summer weighs about 180-200 pounds. They are considerably lighter when they emerge

from winter dormancy and may be

twenty percent heavier in the fall when they are fat.

The color of this bear over its entire range varies from jet black

to white. A very rare white or creamy phase occurs on Gribble Island

and vicinity in British Columbia. Three colors are common in Alaska.

Black is the most often encountered color but brown or cinnamon bears

are often seen in Southcentral Alaska. The rare blue or glacier phase

may be seen in the Yakutat area and has been reported from other

areas. Nearly all blacks have a patch of white hair on the fronts of

their chests.

Blacks, even the white color phase, always have brown muzzles.

They are most easily distinguished from brown/grizzlies by their

straight facial profile and their claws which are sharply curved and

seldom over one and one-half inches in length. Positive

identification can be made by measuring the upper rear molar which is

never more than one and one-fourth inches wide in the black bear and

is never less than that in the brown/grizzly bear. The size of black

bears is often overestimated.

Black bears have very poor eyesight but their senses of smell and

hearing are well-developed.

LIFE HISTORY: Mating takes place in June-July. Apart from that

time, blacks are usually solitary, except for sows with cubs. Cubs

are born the following February-March while their mothers are in

their dens. The gestation period is about seven months. The cubs are

blind, nearly hairless and weigh only a few ounces at birth. Upon

emerging from the den in May they weigh about five pounds and are

covered with fine wooly hair. They are able to follow their mothers

quite well. One to four cubs may be born but two is the usual number.

Cubs apparently remain with their mothers through the first winter

follow-ing their birth. Apparently sows breed yearly. Bears become

sexually mature at three to four years of age.

FOOD HABITS: Black bears are creatures of opportunity when it

comes to matters of food. There are, however, certain patterns of

food-seeking which they follow. Upon emergence in the spring, freshly

sprouted green vegetation is the main food item, but blacks will

readily take anything they encounter. Things such as winter-killed

animals are readily eaten, and in some areas black bears have been

found to be effective predators on newborn moose calves. As summer

progresses, feeding shifts to salmon if they are available. In areas

without salmon, bears rely primarily on vegetation throughout the

year. Berries, especially blueberries, are an important late

summer-fall food item. Bears are cannibalistic on occasion.

WINTER DORMANCY: As with brown/grizzly bears, black bears spend

the winter months in a state of semi-hibernation. Their body

temperature drops, their metabolic rate is reduced and they sleep for

long periods. This is not considered true hibernation as they do

occasionally emerge from their dens. Bears enter this dormancy period

in the fall, after most food items become hard to find and emerge

again in the spring, when food is again available. In the northern

part of their range, bears may be dormant for as long as seven to

eight months. Females with cubs usually emerge later than lone bears.

Dens may be found from sea level to alpine areas.

HUMAN UTILIZATION: Over most of Alaska, blacks are hunted as game

animals. At one time they were classified as fur-bearers and were

heavily utilized as such. Now there is a growing appreciation for

them as a trophy animal. Blacks are so common and widely distributed

that they often cause damage at homesteads, construction camps, or

even in towns, and are destroyed as nuisance animals. These

depredation kills can be minimized or eliminated if garbage and other

food items which attract them to camps and residences are eliminated.

In some localities of Alaska, black bears are themselves sought as

food. In the community of Huslia, for instance, hibernating bears are

killed, cooked and eaten by the men and boys of the community in a

traditional dinner.

The best bear hunting areas are probably from the tidal areas in

Prince William Sound southward through the panhandle of Alaska. In

these areas, bears are spotted from boats as they forage on the

beach. Late May through early June is usually the best time for such

hunting. The pelts of spring black bears make beautiful trophies if

taken before they start to shed.

If bear flesh is utilized for human food, it must be well-cooked

as Alaskan bears have been known to have trichinosis. This disease is

transmitted by eating infected meat that is not cooked thoroughly.

DANGER TO HUMANS: Bears are extremely powerful animals and

potentially dangerous to humans. They are usually highly cautious and

secretive, but if they have a food supply, they may defend it against

all intruders. Bears are found in highly urbanized areas every year,

in downtown Anchorage and Fairbanks. Encounters with humans,

especially near garbage dumps, fish drying racks, etc., frequently

occur. However, sows with cubs must always be respected. A rule of

thumb is: never come between or near a mother bear and her young. She

will attack.

Normally, these bears snort in a characteristic way and move off.

They have, however, attacked without apparent provoca-tion. Several

persons have been victims of these unprovoked attacks. People have

been maimed and some have been killed every year as a result of such

an encounter with a black bear. In general, all bears should be

considered as potentially dangerous and should be treated with

respect.

Loyal Johnson

Reprinted 1984

click on image for a bigger graphic

the

BEAVER

in Alaska.

click on image for a bigger graphic

Alaska Department of Fish and Game

Wildlife Notebook Series

THE BEAVER (Castor canadensis) is

North America's largest rodent. It is found throughout most of the

forested portions of the state, including Kodiak Island where it was

transplanted in 1925.

GENERAL DESCRIPTION: Beavers in the wild live about 10 to 12

years. In captivity they have been known to live as long as 19 years.

Throughout their lives they continue to grow and may reach three to

four feet (0.9 to 1.2 m) long, including tail. Although most adult

beavers weigh 40 to 70 pounds (17.1 to 31.7 kg), very old, fat

beavers can weigh up to 100 pounds, or 45 kg.

The beaver's heavy chestnut brown coat over a warm, soft underfur

keeps the animal comfortable in all temperatures. Its large, webbed

feet and broad, black tail (about 10 inches long and six inches wide,

or 25 cm long and 15 cm wide) can be used as a rudder when swimming.

When slapped against the water it serves as a sign of warning, but it

can be used as a signal for other emotions as well. When the beaver

stands up on its hind legs to cut down a tree, the tail is like a

fifth leg used for balance.

A perfectly designed swimmer, the beaver's nose and ear valves

close automatically under water. Beavers' lips are loose so they can

be drawn tightly behind the protruding teeth. In this way a submerged

beaver can cut and chew wood without getting water in its mouth.

LIFE HISTORY: Beavers must be assured of two or three feet (0.6 to

0.9 m) of water year-round. Water serves as a refuge from their

enemies and they build canals to float and transport heavy objects

(food and lumber). Food for winter use must be stored under water as

well.

If the habitat does not have the necessary water level, beavers

construct dams. Each dam is a little different. A beaver works alone

or with family members to build a dam. They pile logs and trees and

secure them with mud, masses of plants, rocks and sticks. Although

the average size used for construction of a dam is four to twelve

inches (10 to 30 cm) across the stump, use of trees up to 150 feet

(45 m) tall and five feet(115 m) across have been recorded. As the

tree snaps, the beaver runs! Very large trees are not moved but the

bark is stripped off and eaten. Smaller trees are cut into movable

pieces, dragged into the water and through their canals, and finally

used for repairing dams and lodges. This work is done mainly in

autumn.

The den is used as a food cache, rearing area and general home.

Dens are for two types depending on water level fluctuations. Some

are simply dug into the stream bank and others are lodges constructed

of sticks and mud.

Where streams are too large or swift to dam but provide ample

water throughout the year, the beavers may burrow into a bank. These

may have several tunnel exits with at least one above high water mark

and another below low water mark. The den itself is a large chamber

averaging two feet wide by three feet long by three feet high (60 cm

by 90 cm by 90 cm).

Stick lodges are the homes for most beavers in Alaska. These

lodges never look alike, but they have two things in common: (1) the

bank dens have one chamber-like room, (2) at least one tunnel exit is

in deep water so it will be free of winter ice. This also provides

quick and easy access for food gathering and emer-gency escape from

predators. Each year beavers will add materials to the lodge whether

or not repairs are necessary. The same lodge is used by a beaver

family year after year so some can be quite large. It is the family's

home year-round.

After mating (which takes place in January or February) the female

prepares for a new litter. One to six kits are born in late April to

June. Their eyes are open at birth and they are covered with soft

fur. They can swim immediately. The young beavers live with their

parents until they are two years old. Then they leave to find their

own homes.

FOOD HABITS AND PREDATORS: Life in a beaver colony depends largely

on food supply. Beavers eat not only tree bark, but also aquatic

plants of all kinds, roots and grasses. As they exhaust the food

supply in the area, the beavers must roam farther from their homes.

This increases the danger from predators. When an area is cleared of

food, the family migrates to a new home. In Alaska wolves, lynx,

wolverine, bears and of course humans are important predators of

beavers.

ECOLOGY AND ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE: As beavers cut down small trees

and clear away brush, they provide places that are ideal food patches

for some animals. Waterfowl might use these spots as feeding and

nesting grounds, and ponds created by beavers often serve as fish

habitat. Occasionally beaver dams may block streams to migrating

anadromous fish like salmon, and at times road culverts may be

blocked or other human developments flooded by this industrious

animal.

In the past beaver pelts were so important they were used as a

trade medium in place of money. Between 1853 and 1877, the Hudson Bay

Company sold almost three million beaver pelts to England. In Alaska

today, trappers still take the furs. They are highly-prized for cold

weather coats and hats.

Peter Shepherd

1978

click on image for a bigger graphic

|

the

MUSKRAT

in Alaska

click on image for a bigger graphic |

|

Alaska Department of Fish and Game

Wildlife Notebook Series

THE MUSKRAT (Ondotra zibethica)

occurs throughout most of Alaska's mainland except some islands of

southeastern Alaska, the Alaska Peninsula west of Ugashik Lakes and

the Arctic Slope north of the Brooks Range. The highest populations

of muskrat are in the broad floodplains and deltas of the major

rivers and in marshy areas dotted with small lakes.

Muskrats are one of Alaska's most visible fur-bearers and rank

first in numbers of animals harvested in Alaska and among the top

five in value. Four-fifths of the muskrats harvested in Alaska are

taken in five areas: the Yukon Flats surrounding Fort Yukon, Minto

Flats, Tetlin Lakes, the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta and the

Selawik-Kobuk-Noatak area. Muskrats are common in ponds and lakes

along the road systems in the Southcentral and interior parts of

Alaska.

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS: Often mistaken at first glance for the

beaver, the muskrat's small size--only two to four pounds--and its

long, scaly rat-like tail are the most immediate identification

marks. They are 10 to 14 inches in length, excluding their 8- to

11-inch tails. Their coats consist of soft, dense under-fur and long,

coarse, shining guard hairs which produce the dominant color of the

upper parts. Coloration ranges from a medium silvery brown to dark

brown with a lighter belly. The feet and tail are dark brown or

black. In open, swampy areas muskrats construct houses of vegetation

piled into mounds two to three feet above the surface of the water

and five to six feet in diameter. They also tunnel into earth banks.

Their nests are well above high water and have tunnels exiting

underwater below the lowest freezing level. Muskrats construct slides

and make fairly well-defined channels through vegetation along banks

of streams and ponds.

LIFE HISTORY: Muskrats have both a high reproductive and

population turnover rate. Mature females usually have two litters per

year and annually give birth to 15 young, or seven to eight per

litter.

Mating begins as soon as there is open water in the spring; in

interior Alaska this date may range from late April to mid-May and

the young resulting from this first mating are born in early to

mid-June. Females mate again three to five days after the birth of

the first litter. Their second litter is born about 25 days later.

Thus there are two peaks in breeding activity separated by about 30

days.

Evidence indicates that male muskrats remain at the same den with

the female for several weeks. The young are weaned at about one month

of age, but may stay with the parents for a while longer. Second

litters often over-winter in the same den with their parents.

Muskrats' sexual maturity is reached at about nine to ten months of

age.

FOOD HABITS: Muskrats are basically herbivorous and feed

mainly on

aquatic plants such as the roots and stems of cattails, lilies,

sedges and grass. They may occasionally eat some animal life such as

mussels, shrimp and small fish. Vegetation is collected and stored

during the summer for winter use. Throughout the winter muskrats

remained below the ice for great periods of time eating this stored

food and submerged vegetation. They extend their feeding areas by

constructing "pushups" which are piles of vegetation deposited on the

surface of the ice over an opening. Muskrats bring vegetation to

these pushups and eat it there. Continual use keeps the pushups free

of ice.

As the ice increases in thickness during the winter, less and less

area is available for foraging. Muskrats are forced to leave shallow

ponds or spend their time in deeper ponds to search for food. Deep

ponds and channels often have less aquatic vegetation than shallower

ones, thus they can support fewer muskrats. As muskrats compete for

deeper areas, food supplies are depleted rapidly. This may result in

exhaustion of food supplies and consequent fighting, starvation or

emigration of the muskrats. There are seldom any unoccupied living

spaces available and the emigrants may freeze, starve or are killed

by predators.

ECONOMIC USE: The open season for harvesting muskrats in

most of Alaska begins around November 1 and closes between the end of May

and

the 10th of June, though practically all muskrats are taken in the

last month of the season. The fall and winter season was initiated to

encourage the harvest of muskrats before they were lost to "winter

kill," but there is little trapping then. Eighty percent of the

muskrats harvested in Alaska are taken with a .22-caliber rifle. A

small amount of trapping (which is far more time-consuming than

shooting) takes place in the spring before ice breakup. Only a small

proportion of the total muskrat habitat is hunted or trapped.

Transportation during the open season is almost entirely by boat, and

only the larger streams, ponds and lakes that can be reached by short

portages are hunted. Unhunted areas act as natural reservoirs of

muskrat populations which serve to repopulate heavily harvested

areas. Muskrat fur is beautiful and durable and the meat of muskrats

is very tasty and very usable as human food.

OBSERVATION: During the summer, muskrats may be observed going

about their daily activities in just about every roadside pond and

slough where there is suitable vegetation as a food source. Often the

casual observer will hear a big splash and see something swimming

around in the water, giving the impression that the pond is inhabited

by large fish which are jumping and surfacing. Indeed, sometimes

there are large pike in the grassy sloughs feeding on an occasional

muskrat! If the viewer sits quietly by the edge of the pond or

slough, the resident muskrats will soon go about their business,

providing hours of entertainment.

Jean Ernest

1978

click on image for a bigger graphic

|

the

HARE

in Alaska

click on image for a bigger graphic |

|

Alaska Department of Fish and Game

Wildlife Notebook Series

THERE ARE TWO SPECIES of hares in Alaska, both of which turn white

in the winter. THE

SNOWSHOE, or varying

hare (Lepus americanus) is the most common and widespread of

these. It is distributed over the state except for the lower

Kuskokwim Delta, the Alaska Peninsula and the area north of the

Brooks Range. It is sparsely distributed along the Southeastern

mainland except for major river deltas. THE

TUNDRA, or arctic, hare (Lepus 0thus) populates much of

the western coast of Alaska, including the Alaska Peninsula, but has

a spotty distribution along the arctic coast and the north slope of

the Brooks Range.

Hares are often called "rabbits" and both are members of

the

family Leporidae. However, hares are born fully furred and with eyes

open, while newborn rabbits are blind and hairless. Newborn hares are

soon able to hop around and leave the nest, but the helpless baby

rabbits do not even open their eyes for seven to 10 days.

GENERAL DESCRIPTION: Snowshoe hares are somewhat larger

than a

cottontail rabbit (Genus Sylvila-gus). They average around 18 to 20

inches in total length and weigh three to four pounds. In summer the

coat is yellowish to grayish brown with white underparts, and the

tail is brown on top. This coat is shed and replaced by white pelage

in winter, but the hairs are dusky at the base and the underfur is

gray. The ears are dark at the tips. The large hind feet are

well-furred, adapting these animals for the deep snows of the boreal

forests--hence the name "snowshoe."

The arctic hare is larger 22 to 28 inches in length and weighs six

to 12 pounds. The winter coat of this large hare is long and the fur

is white to the base. Edges of the ears are blackish. In summer the

coat is grayish brown above and white below, with a whitish base to

the hairs. The tail is entirely white.

LIFE HISTORY: Snowshoe hares breed at about one year of age, and

have two to three litters per year. The gestation period is 36 to 37

days. First litters are born around the middle of May in Interior

Alaska, and average about four leverets (young hares). The second

litter, in years of increasing abundance, often averages six young,

and occasionally there is a third litter. Females breed immediately

after the birth of a litter.

The leverets are born in an unlined depression or "form." They

weigh about two ounces at birth and can walk by the time their fur is

dry. In a day or two they are wandering about the nest, and in less

than two weeks will be eating green vegetation. They nurse for about

a month. The color pattern of the young snowshoe is similar to the

summer pattern of adults.

Breeding habits of the arctic hare are similar, but the

reproductive season usually begins later and there is probably only

one litter per year. The leverets are darker than the adults, with a

black tinge to their fur.

HABITS: Snowshoe hares are found in mixed spruce forests, wooded

swamps and brushy areas. They feed on a wide variety of plant

material--grasses, buds, twigs and leaves in the summer and spruce

twigs and needles, bark and buds of hardwood such as aspen and willow

in the winter. The arctic hare is generally found on windswept rocky

slopes and upland tundra, often in groups. These big hares usually

avoid low-lands and wooded areas. They feed on willow shoots and

various dwarf arctic plants.

Hares are most active at dusk and dawn. They do not dig burrows or

build nests, but use natural shelters and depressions and-rest under

branches or bushes. The snowshoe hare travels about on

well-established trails or runways which become deeply worn in the

snow or forest floor. It is interesting that the winter trails

through the deep snow follow the summer pathways.

Populations of snowshoe hares are subject to cycles of high

abundance and scarcity. The population in an area will build up over

a period of years to a peak of abundance, followed by a sudden

decline to a very low level. During periods of peak abundance there

are as many as 600 animals per square mile of range. The exact cause

or causes for the decline are unknown; some possibilities are shock

disease due to stress, disease, parasites or a combination of these.

ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE: Snowshoe hares are one of the more important

food items of northern furbearers, particularly lynx. They are often

an important source of food for Alaskans. The arctic hare is also

important as a source of food and fur.

In times of great abundance the snowshoes may kill brush

by

overbrowsing. In "high" years they may compete with big game animals

such as moose for forage.

Both species of hares offer a great deal of recreation for the

small game hunter, especially in years of abundance. The arctic hare

provides an unusual trophy and a considerable amount of meat. The

snowshoe is available to more hunters, and can be taken near highway

systems and in such disturbed areas as mine tailing piles. Hares are

best hunted with a shotgun and birdshot, or .22-caliber rifle or

handgun. Early snowfalls will often catch the snowshoe hare still in

its summer coat, making it vulnerable to the hunter. The meat is

quite tasty.

Hunters should be alert for signs of tularemia, a bacterial

disease found in hares and rodents throughout the world. Such signs

include general sluggishness and spots on the liver and spleen.

Normal sanitary precautions should be taken when handling hares and

rubber gloves used when cleaning and dressing them. The meat should

be cooked thoroughly.

Jeannette R. Ernest

1978

click on image for a bigger graphic

|

the

PORCUPINE

in Alaska

click on image for a bigger graphic |

|

Alaska Department of Fish and Game

Wildlife Notebook Series

THE PORCUPINE (Erethizon

dorsatum),

commonly known as "porky," "hedgehog" or "quill pig," is second in

size only to the beaver among the rodents of Alaska. Fossilized

remains of porky and his im-mediate ancestors indicate that he has

been a part of the North American fauna since the late Cenozoic era,

or about 20 to 30 million years.

GENERAL DESCRIPTION: This stout, short-legged animal is 25 to 31

inches long and, except for the foot pads and nose, is covered with

hair and quills of varying length. The hair on the belly is sparse.

The color varies from black to brown. The tips of the long guard

hairs are lighter and give the coat hues of yel-low or white. The

tail is short and thick and heavily covered with quills. The average

weight of an adult porcupine varies between 15 and 18 pounds, but

certain individuals will weigh up to 25 pounds. The peculiar pelage

of the porcupine makes it unique among the mammals of the Western

Hemisphere. The quills are hollow, modified hairs which are well

barbed on as much as two-thirds of the outer end. Quills from

different parts of the body vary in length, flexibility, color, shaft

diameter and scaliness.

LIFE HISTORY: Breeding takes place in November, with a male

usually breeding with only one female. After a gestation period of

about 16 weeks, a single offspring is born. At birth, the young

porcupine weighs between one and two pounds and is about 10 inches

long.

Its eyes are open and its body is covered with long, grayish-black

hairs. Within a matter of hours, the devel-oping quills are dry and

serve as protection. The young porky is then capable of following the

female. The newly born porcupine nurses for a day or two and is then

able to eat vegetation. At the end of the first summer, the young

porcupine weighs about three to three and a half pounds and is about

18 inches long. Porcupines mature at three years of age and then

wander long distances from the home den.

Being an opportunist when it comes to shelter, the porcupine

utilizes any natural cavity which protects it from the elements. Such

shelters are rock or earth dens, cavities under deadfalls, roots,

stumps or hollow logs.

Ordinarily, the porcupine relies largely upon its sense of smell

for most of its activities. Hearing seems to be fairly good but its

sight has been reported as poor. Porcupines sometimes whine and utter

low grunts.

In general, the coat hairs and quills serve as protection against

inclement weather and predators. Depending upon the structure and

location on the body, they also function as touch receptors, sexual

stimulators and support for climbing.

Porcupines are normally nocturnal. However, they can be seen

slowly plodding about at any time of day. Tree climbing is generally

slow and awkward. As it methodically hitches its way up a tree, it

may use the stiff bristles on the undersurface of its tail as a

support. Thus, the lower tail bristles are often considerably worn by

the use of the tail for climbing and balancing.

FOOD: Spruce bark is a major part of the diet and may be

considered the porcupine's primary food in the winter. Birch also is

important. In the summer, a wide variety and abundance of green

leaves, buds and aquatic plants are eaten in preference to bark.

Porcupines are especially fond of the salty taste of perspira-tion on

axe handles, canoe paddles and shovels. They also feed upon discarded

antlers and the bones of dead animals and thus obtain phosphorus and

calcium.

PREDATION AND DEFENSE: Most carnivores would not pass up a good

meal of porcupine. However, an encounter between a young or

inexperienced predator or dog and a porcupine can be a very painful

exper-ience for the predator. Many unfortunate carnivores have

painfully starved to death with a mouthful of quills. Not only is the

skin surface of the animal involved, but the barbed quills also work

their way into the tissues. Predators usually can kill porcupines

only by flipping them on to their backs where the soft, quill-less

belly can be ripped open. The animal is then eaten, leaving an empty,

quill-covered sack. This method of killing porcupines is commonly

practiced by fishers and occasionally by lynx, wolves, coyotes and

wolverine.

When the animal is relaxed, the hair and quills lie flat and point

backward. When startled, the porcupine can draw up the skin of the

back to expose the quills. If touched on the hind quarters, it may

flip its tail, thus adding force to drive quills into its attacker.

Unlike other animals when faced with danger, the porcupine presents

its most formidable bristling back. Thus, the attacker faces a nearly

impenetrable forest of quills. Although a porcupine cannot throw its

quills, loose quills may be dislodged and this could give the

impres-sion that they are being thrown.

ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE: Because of its slow, ploddy movements, the

porcupine can be readily ap-proached and killed with a club. This

trait is detrimental to the individual animal but it has saved the

lives of many starving trappers and prospectors. This in itself is

reason enough to give the animal a certain amount of protection in

case such emergencies arise. Although the meat is not the most

palatable, it is edible and at times is a very welcome addition to

the diet.

Quills were utilized for decoration at one time by most of the

Indian tribes of Interior Alaska. They were dyed with locally

obtainable vegetable materials, flattened and then sewn into skin

clothing and other items.

Porcupines can be very injurious to mature forests and

reforestation projects because they feed on the bark and growing

layer during the winter and on the buds, leaves and tender branches

during the summer. When such problems occur, control may be

justified. However, needless killing or eradication should be

discour-aged. Porcupines are an integral part of the Alaskan faunal

scene and should not be thought of as pests merely because they are

not as economically important to man as some other species.

Dennis Bromley

Revised and reprinted 1978

click on image for a bigger graphic

|

the

KING SALMON

in Alaska

click on image for a bigger graphic |

|

Alaska Department of Fish and Game

Wildlife Notebook Series

THE KING SALMON (Oncorhynchus

tshawytscha) is Alaska's state fish and is one of the most important

sport and commercial fish native to the Pacific coast of North

America. It is the largest of all Pacific salmon with weights of

individual fish commonly exceeding 30 pounds. A 126-pound king salmon

taken in a fish trap near Petersburg, Alaska in 1949 is the largest

on record.

The king salmon has numerous local names. In Washington and

Oregon, king salmon are called Chinook, while in British Columbia

they are called spring salmon. Other names are quinnat, tyee, tule

and blackmouth.

RANGE: In North America, king salmon range from the Monterey Bay

area of California to the Chukchi Sea area of Alaska. On the Asian

coast, king salmon occur from the Anadyr River area of Siberia

southward to Hokkaido, Japan.

In Alaska, it is abundant from the Southeastern panhandle to the

Yukon River. Major populations return to the Yukon, Kuskokwim,

Nushagak, Susitna, Kenai, Copper, Alsek, Taku and Stikine rivers.

Important runs also occur in many smaller streams.

GENERAL DESCRIPTION: Adults are distinguished by the black

irregular spotting on the back and dorsal fins and on both lobes of

the caudal or tail fin. King salmon also have a black pigment along

the gum line which gives them the name "blackmouth" in some areas.

In the ocean, the king salmon is a robust, deep-bodied

fish with a bluish-green coloration on the back which fades to a silvery

color on

the sides and white on the belly. Colors of spawning king salmon in

fresh water range from red to copper to almost black, depending on

location and degree of maturation. Males are more deeply colored than

the females and also are distinguished by their "ridgeback" condition

and by their hooked nose or upper jaw. Juveniles in fresh water are

recognized by well-developed parr marks which are bisected by the

lateral line.

LIFE HISTORY: Like all species of Pacific salmon, king salmon are

anadromous. They hatch in fresh water, spend part of their life in

the ocean and then spawn in fresh water. All kings die after

spawning.

King salmon may become sexually mature from their second through

seventh year and as a result, fish in any spawning run may vary

greatly in size. For example, a mature three-year-old will probably

weigh less than four pounds, while a mature seven-year-old may exceed

50 pounds.

Females tend to be older than males at maturity. In many

spawning runs, males outnumber females in all but the six- and seven-year

age

groups. Small kings that mature after spending only one winter in the

ocean are commonly referred to as "jacks" and are usually males.

Alaska streams normally receive a single run of king salmon in the

period from May through July.

King salmon often make extensive freshwater spawning migrations to

reach their home streams in some of the larger river systems. Yukon

River spawners bound for the extreme headwaters in Yukon Territory,

Canada, will travel more than 2,000 river miles during a 60-day

period.

King salmon do not feed during the freshwater spawning migration

so their condition deteriorates gradually during the spawning run as

they utilize stored body materials for energy and for the development

of reproductive products.

Each female deposits from 3,000 to 14,000 eggs in several gravel

nests, or redds, which she excavates in relatively deep, moving

water. In Alaska, the eggs usually hatch in late winter or early

spring, depending on time of spawning and water temperature.

The newly hatched fish, called alevins, live in the gravel for

several weeks until they gradually absorb the food in the attached

yolk sac. These juveniles, called fry, wiggle up through the gravel

by early spring.

In Alaska, most juvenile king salmon remain in fresh water until

the following spring when they migrate to the ocean in their second

year of life. These seaward migrants are called smolts.

Juvenile kings in fresh water first feed on plankton, then later

eat insects. In the ocean, they eat a variety of organisms including

herring, pilchard, sandlance, squid and crustaceans. Salmon grow

rapidly in the ocean and often double their weight during a single

summer season.

COMMERCIAL FISHERY: Worldwide king salmon catches during 1967-71

averaged slightly more than 3.5 million fish per year. The United

States harvested approximately 52 per cent of these fish, while

Canada took 33 per cent; Japan 12 per cent and Russia 3 per cent.

Alaska's annual harvest during this period averaged about 639,000

fish per year, or about 21 per cent of the North American catch. The

majority of the Alaska catch is made in the Southeastern, Bristol Bay

and Arctic-Yukon-Kuskokwim areas. Fish taken commercially average

about 18 pounds. The majority of the catch is made with troll gear

and gill nets.

There is an excellent market for king salmon because of their

large size and excellent table qualities. Recent catches in Alaska

have had first wholesale pack values approaching $6 million and

brought fishermen nearly $4 million per year.

SUBSISTENCE AND SPORT FISHERY: Catches by Eskimo and Indian

subsistence fishermen in the Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers have averaged

about 60,000 king salmon annually in recent years. The king salmon is

perhaps the most highly prized sport fish in Alaska and is

extensively fished by anglers in the Southeastern and Cook Inlet

areas. Trolling with rigged herring is the favored method of angling

in salt water while lures and salmon eggs are used by freshwater

anglers. The sport fishing harvest of king salmon is over 26,000

annually with Cook Inlet and adjacent watersheds contributing over

half of the catch.

Ron Regnart

Stan Kubik

Revised and reprinted 1978

click on image for a bigger graphic

Introduction

ANE Curriculum

Overview

Unit Overview

Athabascan

Art Sampler

OCR SCANNED MATERIAL