“

What would you like to be when you grow up?” he slowly

asked the Eskimo boy. The boy looked at him and giggled,

seeming not to understand the words. The bush pilot tried

again to communicate

his question. This time he used big expansive arm movements

to help convey his meaning.

“

Grow up.” He stood up using his hands to express growth

and pointed to the laughing boy. This time he saw a glimmer

of recognition in the boy’s face.

“

Great whaling captain,” the boy responded as if he

had been asked this question before, and the words had

been rehearsed.

The pilot nodded. But, as he did, he wondered

if “whaling

captain” would exist as a livelihood when the boy

grew up. He had seen many changes in other native villages

over the

last few years, and a inexplicable sadness touched him.

They

sat together for awhile, looking out over the barren ice

flow. Soon the sun began to turn into a glowing ember

as it

set on the curved horizon, orange at the middle, surrounded

by a

burning red. This seemed to be a signal to both of them

to get up from the overturned boat they had been sitting

on and

head

back toward the village.

While they walked, the boy began

to sing a song in his native language. The pilot did

not understand the words,

but it seemed

a plaintive song, perhaps a song of mourning or loss. Or

maybe, he thought hopefully, it was a song of joy sung

slowly and

quietly.

As they arrived at the shack that was the boy’s

home, the warmth of the room mingled with the smell of

seal made this truly

a haven against the cold and hunger lying just a few feet

out the door.

The soft glow of oil lamps lighted the cooking

area and table. A woman stood at a cutting board carving

pieces

of muktuk from

a slab of whale. As she cut, the rocking motion of her

arm was making full use of the ulu. She turned and laughed

when

she saw

her son and the pilot.

“

Tuuvick” she said with a smile spreading over her moon-shaped

face. Tuuvick ran over to his mother and words started to spill

out of his mouth.

“

No, Tuuvick, use your English,” she said, nodding her head

toward the pilot.

“

We were sitting and watching,” Tuuvick said slowly.

“

Watching for what?” asked his mother as she brought over

food to set on the table.

“

For father to return,” he said anxiously, looking

up at his mother.

She laughed and said, “You know,

many more days before your father returns. He is on very

important hunting trip.”

As Tuuvick and his mother

talked, the pilot took off his parka and sat by the oil

stove, warming his hands over

the metal

that encased the source of heat for this house. As he sat

he noticed

in the corner a small pile of furs in many different shades.

The fur was used as a ruff around little carved Eskimo

faces hanging on the wall.

The pilot stood up to examine

the faces closer. It struck him how all the faces were

smiling. He thought they looked

like

perfect replicas of the faces in the village. Even though

he had just arrived the day before, all of the villagers

he had come

in contact with were warm and welcoming.

“

Kasak, who made these faces?” he asked as he turned to

walk over to the table and help himself to some of the food.

“

My aunt made most of them and she taught me, so now I make them

too,” Kasak answered. “They aren’t much, but

the last pilot that was here to drop off supplies paid us one

dollar apiece for them.”

“

I would like to buy as many of these as you have. And I

will give you two dollars apiece for them.”

Laughing,

Kasak replied, “One dollar seems more than enough.

They are made from old scraps that have no other use.”

With

a wave of her hand, she motioned Tuuvick and the pilot

to sit at the table and eat. Some of the food was familiar

to the

pilot as he was the one that brought it to the village.

There before them were canned peaches--a delicacy in the

far north, pilot bread--Kakurrak, and, of course, cans

of Pepsi.

They finished their meal and Kasak began to ask

questions. Did the pilot know any of their families’ relatives

that had moved from the village to what they considered

the big city

--Fairbanks? He said yes, he had met some of her family

at potlucks held at the church. This was not the complete

truth and

Kasak seemed to sense that.

“

I hear stories of drinking and reports that one of our

cousins is in jail?” she asked.

For the first time,

the pilot noticed a frown on Kasak’s

face.

In the five years the pilot had been in Alaska, he

had watched many natives move from the villages to Fairbanks.

Some did

well. Others had a difficult time adjusting to the white

man’s

way of doing things. The drinking problems had given the

natives a bad reputation in Fairbanks. But he didn’t

want to shame Kasak with the details of her family members

drinking

and getting into fights.

“

Yes, there is some drinking going on downtown, but for

the most part everybody gets on pretty well,” he

tried to explain. “It’s

just that there is not much to do during the winter months

and sometimes people just go stir crazy.”

He tried

to keep a light conversational tone to his voice. However,

he knew the problem went deeper than just a few

people occasionally

drinking.

Again, Kasak frowned at these words. The winters

had always been long. This was a time to visit and tell

stories while

drinking

tea, a time to sew and repair parkas and mukluks.

“

Don’t they have any work to do in Fairbanks?” Kasak

asked as she stood up to clear the table.

“

There is work, but most of it requires training,” explained

the pilot. “Some of the villagers are working as

construction workers, but during the winter there is no

building going on.”

At that moment they heard the

dogs outside barking and the door burst open. There stood

a group of smiling and

laughing

women

and children. Most of the men were out on the hunt and

the women of the village had heard that Kasak was entertaining

the

pilot.

While the pilot taxied down the frozen runway, he

thought of the last words he had with Kasak this morning

on the

tarmac

before takeoff.

“

Take these , for no money,” Kasak said, as she handed him

a bag filled with the Eskimo faces he had so admired. He started

to protest, but she waved his words away. “Give some of

them to our family in Fairbanks. Tell them they are from our

village,” she added.

“

I’ll do that,” he said as he took the bag, and looked

at Kasak.

“

I know.” She held his eyes for a moment, then walked

away to join the others who had gathered around to see

the pilot go.

As he climbed toward the Arctic sun, he looked

down to

see the villagers gathered around waving good-bye. Many

colors

of parkas

with laughing faces turned up to the sky stood by the

runway. Disappearing into the dawn, he looked beside

him at the

bag of smiling faces that were his friends.

Fathers

Jan Westlake

Kiana

7th grade

Fathers show us how to hold our gun

when we are just young boys.

How to hold the ax to cut

the wood we use.

His hands so strong

sets a trap to catch a wolverine.

Our little hands are shown the way

by dad’s touch.

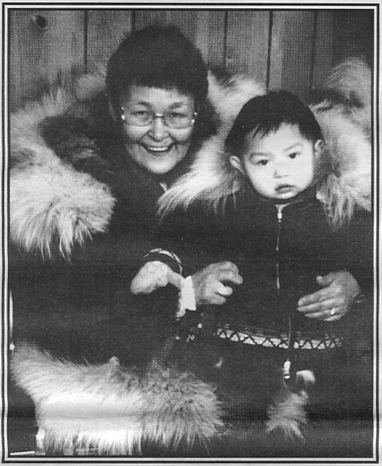

Photo courtesy of Christine Aklalook

Bert Flood Jr.

Kiana

7th grade

Mother cooks the soup so warm and delicious.

Dad saws the wood that heats the house.

Auntie helps clean the house no dirty houses.

I fish for the long

winter season.

Family Roles

Micheline Baldwin

Kiana

8th grade

Family Roles is an important value for the Ińupiaq

people. Starting with the grandmothers, she looks after

the extended family. She needs to know where everyone

is and make sure they are alright.

The grandmothers, also

known as “Aana,” usually

go out to visit their friends or just stays in and

sews or knits.

Grandfathers, “Taata,” are

also very important. They give advice on survival for

hunting and camping

trips.

Mothers have a lot of work to do. They have to

process meat, dry fish, tan skins and wash the clothes

and

dishes. But the mother’s most important role

is to be responsible for their children, both physically

and emotionally.

They usually sew to relax when they are done with their

daily work.

Fathers have a lot to do. They do the hunting,

gather wood and mostly outside activities. They also

have

to give advice

on hunting and safety tips to the boys.

The daughters

to a lot of work around the house. They clean and help

their mothers and grandmothers

with

their chores,

like hanging fish and more. The boys help their

fathers by doing subsistence hunting and fishing. They

also

chop the wood and bring it in the house.

The Aunts

usually help around the house and make caps and other

clothing. The uncles help the other

men in

the family

by hunting and other outside jobs.

Nowawdays,

the roles of the Inupiaq people are not always practiced.

Because of this, there

have been

a lot of suicides

and drug and alcohol abuse. That is why it

is important to pass on the Inupiaq values, so they

will help

people know what their responsibilities are.