The Arctic Venturer:

The Arctic Venturer:

Preserving the Iñupiaq Values

Sherry Ballot

of Buckland

Mt. Edgecumbe High School

Young Percy, at the age of eight, was watching his

father drive the boat, looking up at him with great admiration, because

his father asked him to hunt Beluga with him for the first time. As they

were

driving down the Buckland River and headed for Elephant Point, which is

in the Kotzebue Sound, Percy was amazed and excited.

He grew more impatient

and it seemed like forever to get to the camp. Finally, as they reached

the camp it began to get dark. So they settled in. But

Percy was still impatient. He kept begging, “Papa, can we go now?”

His

father told him, “Son, we must wait for the tide to go down a little

if we want to get a catch. You rest now so you can stay awake when we

are hunting because it’s going to be a long ride.”

“

Okay,” he replied. As the night went on, Percy woke up still

eager to go on. A few hours later, the waters were ready to ride

and his father

prepared.

Percy jumped in the moving boat and was ready for an adventure

he would never forget. He looked out of the boat, searching for

any site of

a beluga. Meanwhile,

he heard his father shouting at him to look north. There, half

a mile away, he saw a white beluga. Above were seagulls flying in circles.

The boat

raced towards the whale. Then they noticed there were three more

belugas.

In order to catch as many as they could, they needed a

plan. One after the other, they threw their harpoons at the target. Each

of the mammals

got hit.

It was a great day for the hunters!

As they brought home their

trophy, Percy felt courageous. He looked again at his father with pride

and said to himself, “Someday, I’ll

be like my father.”

And, from then on, Percy Ballot has

been a great hunter in our community. From his early childhood,

through his adulthood,

hunting

has always

been a driving force in his life, one that he plans to teach

the younger generation.

Throughout his life, Ballot devoted

himself to everything. He committed his time and effort to gaining an education

at

Mt.

Edgecumbe High

School. Although

he was a quiet student, he strove to make honor roll. He

built his strength as well as his knowledge by participating in basketball.

However,

dedicating his love toward his family bonded them together. Hunting with

his father brought them closer to

each other. Camping

alone with his

wife, June, gave them an opportunity to freshen their relationship.

Being far away from his daughter, who attends Mt. Edgecumbe

High School, gave

him an open friendship with her, and their love grew stronger.

Today,

he gives up his spare time to work for worthy causes. He is on the Regional

Federal Subsistence Board and the

Northwest Arctic

Borough

School Board. He is a local school board member. He was

president of the Indian

Rural Affairs office in his village. He stuck with his

goals and

accomplished them with self-respect.

Learning the basics

of hunting during childhood had an incredible impact on Percy’s life.

Knowledge is the power in a successful hunt. Being cautious in certain

areas, having the survival skills and preventing

accidents makes the hunt more effective.

The Inupiaq

Values influenced young Ballot. Respect for nature is vital because he

needed to learn how

to respect

the land

and animals

before

he was able

to hunt. In order to be allowed to hunt, he had to

work hard. Sharing the carcass of the beluga, caribou

and

other game

with the Elders

is another

value. While he was young, hunting taught him responsibility

Guiding

the younger generation to learn the traditional ways of hunting made Ballot

a stalwart teacher. Through

his insistence,

he begins

teaching his

sons when they are seven. He taught Bruce, the

oldest, and he taught

Richard, who is nine years old. Ballot teaches

them the values first, then he shows

them the basics of hunting.

The students he teaches

are always eager to be there when he tells them to meet him at a certain

place.

They listen

and

pay attention

to every

instruction.

They become anxious when getting ready to hunt.

His own knowledge increases as well as the pupils

while

he is

teaching them.

Ballot believes that hunting affects

the past, present and future. He wants to preserve the

Native values

by giving the young ones

knowledge. His plan

is to keep them out of drugs and into cultural

activities. Through the

education of the young, Percy has become a

valued resource. Ballot understands the values and importance

of hunting

while

growing

up. He is determined

to

keep this tradition in use throughout his life.

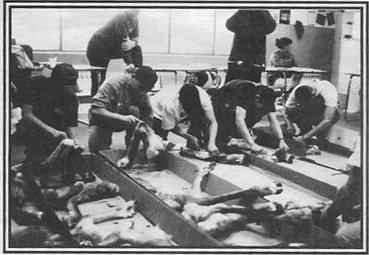

Photo courtesy of Hannah Loon/NANA

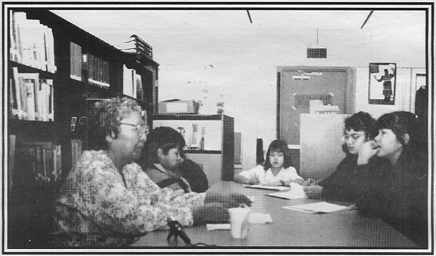

Photo courtesy of Noorvik High School

Responsibility

to Tribe: Education

Berda Wilson

Chukchi News and Information Service

I consider education a precious gift,

especially in rural Alaska, where formal education

historically required

exceptional efforts

to obtain

and where distance

learning at Alaska’s rural university

campuses have allowed me to become an “educated

woman” even at

my age.

In 1944, when I was 4, my family

and I were living in the village of Nuuk,

a very

small

fish camp

about 20

miles

east of Nome.

That year,

my dad decided

that my older sister and two older brothers

would attend school in Nome. I wasn’t

old enough to enroll.

Unfortunately, a

devastating diphtheria epidemic erupted

throughout Nome in 1944,

and three

of us children contracted

this dreaded

disease.

My father felt most anxious to

leave Nome for the safety of his own children.

Finally

well

enough

to travel

and considering ourselves

fortunate to be alive, we all moved

back to Nuuk for the winter.

Three years passed before the family

again moved to Nome for school, where

my brother

and I started

first

grade

together. Glen was 9,

I was 7. In

those days, many students attended

school irregularly, especially if,

like our

family, they lived

off the land with a subsistence

way of

life.

My siblings and I started school

at least six weeks late each fall. We

also left

six weeks

early each

spring, if we managed

to attend

at all.

Our family’s

main livelihood was fishing. Survival

meant working constantly not only

to keep our

stomachs full, but to stay warm,

because wood was our fuel for

both heating and cooking.

Life was

hard. I dreamed of a college education,

even as I struggled to

keep up in elementary

school in Nome,

despite

sporadic attendance.

Thankfully, our dad taught us at

home whenever we could not afford

to move

to Nome to attend

school.

Unfortunately, I was just

starting my senior year in 1957 at Nome High

School

when my

college dream

vanished

with

my dad’s death. An old man

at age 72, Dad died of a stroke

complicated by pneumonia. My father

had worked

long and hard during his later

years of life

to raise his young family as

a single parent, even when we children

did not fully appreciate it.

Scholarships

and other financial support for

potential college students

like

me hardly existed

in the

1950s, especially not for Native

women living in

rural Alaska. No one had ever heard

of “audioconference” or “distance

learning” classes. Rural

Alaskans had to be able to move

to Fairbanks, Sitka

or even the Lower 48 to attend

college. Very few, including me,

could

afford such expense.

“ Life was hard. I dreamed of a college education,

even as I struggled to keep up in elementary school in Nome . . . “

In the

1950s and 1960s, a woman in rural Alaska, particularly a Native

woman, was expected to

marry, raise a family

and depend on her husband.

Since educational

opportunities beyond high school

were virtually nonexistent, I

took the “easy” way

out. I married young, even

graduating from high

school as a married woman.

I

worked for many years as a

homemaker, raising a family

of

four boys and

one girl, all the

while keeping

my

dream of attending

college alive.

When Northwest Community College

opened its doors in Nome in

the early 1970s,

I eagerly

began taking

classes.

Unfortunately,

I did

not enjoy

the

support

in my previous marriage that

I have today with my present

husband

to attend the local college

regularly. As a result, not

until the early

1980s, after

I remarried, did I begin to

vigorously pursue college classes

again.

By 1986, I had earned

a Certificate

in Business

from Northwest Community College,

then continued on for an associate’s

degree.

I inched along toward

my two year degree while I

juggled

a full-time

job, family

responsibilities, classes,

homework and

housework.

In January 1989, I became very

ill with an allergic reaction

that caused

my liver

to stop functioning for several

days. My education

dream again faded as

I struggled at first against

death, then

to regain my health.

As I grew

stronger, I thought of college again. I asked myself, “Why

am I doing this? Couldn’t

I be doing something else

that a perhaps would make

me happier,

even just momentarily, than

to attend such grueling

college classes?” As

I thought about it more,

the answer was revealed to

me:

I desperately wanted a college

degree. Sheer persistence

kept me going

until May 1990, when at age

50, I graduated with an Associate

of Applied Science degree

with a major in business.

My

wonderful husband Steven

has proudly attended my graduation

ceremonies.

Without his untiring

support, I would have

failed and probably dropped

out. This man has cooked,

cleaned house and performed

any other

chore, no matter

how menial, to help me achieve

my goal.

I plowed right on

toward a bachelor’s degree in Rural Development.

I cannot let my dream die.

I want the personal satisfaction of earning a bachelor’s degree.

If I can keep up the pace, I will graduate at the end

of Spring semester 1996,

at age 56, along with my 26-year-old daughter,

Melissa, also a candidate

for the same degree. My dream will be realized.

I hope that by fulfilling

it that others will be

motivated to continue

with

their educational

goals

in rural Alaska.

I feel

that education

is the

answer for Alaska Natives

to

meet the challenge of living

in two

worlds. It is also my

sincere hope

that I have

served as

a role

model for my

daughter, who will serve

as a role model in education

for

other

Native

women,

young and old.