|

Lessons Taught, Lessons Learned Vol. I

THE DEVELOPMENT OF AN

INTEGRATED BILINGUAL

AND CROSS-CULTURAL CURRICULUM

IN AN ARCTIC SCHOOL DISTRICT

by

Helen Roberts

Northwest Arctic School District

Kotzebue

This article was originally

presented at the First Congress on Education, of

the Canadian

School Trustees Association, in Toronto, Canada, June 21, 1978.

The reader is asked to keep in mind that the conditions and

processes described in the article were those of the school

district in 1978, and do not necessarily apply today.

If indeed, there is a formula for

developing an integrated bilingual and cross-cultural curriculum,

experience in the Northwest Arctic School District would suggest

the following key elements of the development process:

Basing the curriculum on

the rapidly changing social context, rather than on stereotyped

bicultural (dual society) concepts.

Ensuring local control of

educational policy.

Treating the whole school

curriculum, rather than separating language and cultural

concems off in a fragment of the curriculum.

Being honest, and keeping

curriculum processes clear and simple-developing

simple educational goals and then

achieving them.

Developing school-community

unity by keeping advisory channels open.

The Northwest Arctic School

District operates eleven schools in a 36,000 square mile region

north of the Arctic Circle. It is an Inupiat Eskimo region, but

Inupiaq language has declined in use. The district has set goals

for students in relation to basic skills, life skills and

cross-cultural skills and is pursuing a curriculum development

process which incorporates staff development, community

development and program development.

In this paper, some of the

problems and processes that have occurred in the development of a

community-based curriculum are discussed. An example of the

integrated approach is given, and issues regarding the legal and

funding structures are explored. Finally, some modest guidelines

for the development of an integrated bilingual and cross-cultural

curriculum are offered.

PROBLEMS AND

PROCESSES

School/Community Dissonance: Local

Control

"Long ago when

they built a Council House they built them for a happy

gathering place. They gather together for happy occasions such

as dancing, Eskimo games and feasts. They used the Council

House for teaching Eskimo way of living."

"There were no set

teachers."

"Eskimos are smart. They learn

a person's word of advice."

"We were there in the time when

there was silence ...the time when Eskimo way of living was

like a still water now has become bad like waves

pounding."

"And these young people our

children are living in the white man's way and have become a

part of them. They have become that way and there are no

Council Houses."

"The government is giving the

education to our children today. The information we have told

on the Eskimo culture will be studied by our grandchildren in

the school."

Education in a mass society is

subversive and assimilative, especially in cross-cultural

situations. The strain, or dissonance, between school and rural

communities in the arctic stems in part from the vast differences

between traditional Eskimo learning and "school learning", as

described above by the elders. In traditional Eskimo society

children learned by watching silently, and following the lead of

their elders. Twenty-thousand years of experience in the arctic

environment comprised a sound basis for the cultural content and

educational methods of traditional Eskimo society. But

encroachment of the technological society on rural Alaska has

created an upheaval in Eskimo society, which is characterized in

the schools by a doctrinaire school curriculum unrelated to the

life experience of the people.

Prior to the establishment of

local control of education, the curriculum in rural Alaska was

nothing more than a transplanted program such as could be found in

any school in the lower forty-eight states. The traditions, values

and beliefs of the dominant white middle and upper classes were

those primarily reflected in the school curriculum, and Eskimo

children were discouraged from using their Inupiaq language in the

school. There was no organized course of studies about the State

of Alaska, nor any attention to Native Studies, and three

successive generations of language suppression had all but

eliminated the Inupiaq language. Today, only the older people are

truly fluent, and most entering school children are not speakers

at all.

Local control in rural Alaska has

its roots in the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act which created

regional Native Associations to hold the Native lands and payments

ceded to Native Alaskans in the act. The Northwest Alaska Native

Association (NANA) became the holder of lands in the Northwest

Region, which encompasses the Kobuk, Noatak and Selawik River

Valleys, and the coastal lands between Deering and

Kivalina-traditional lands of the Inupiat people. NANA later

divided into a profit making corporation (NANA Regional

Corporation) and a non-profit association (Mauneluk Association).

Local control of the land stimulated the movement for local

control of education.

Until 1975 most rural

students who wanted to finish high school had to leave their

villages to attend schools operated by the Bureau of Indian

Affairs or the State of Alaska. For Northwest Arctic students,

this meant traveling as far away as Sitka or even the lower

forty-eight. Native Alaskan boarding students rarely got home to

see their families, and had little in common with other students.

During the time they were away at school, they were removed from

village life, and were not learning the traditional skills

important for survival in the arctic. Needless to say, there were

very few high school graduates among Alaska

Natives.

In 1973 a group of rural Alaskan

students (Molly Hootch, et al) brought a class action suit against

the State of Alaska, charging discrimination in the State's

failure to provide a secondary education such that students could

live at home while attending school. The Hootch case was settled

out of court in 1976 (Tobeluk Consent Decree), where it was agreed

that Native boarding high schools were not an equal educational

opportunity compared to the local high schools attended by most

white Alaskans. At the same time, the Alaska Unorganized Borough

Schools (formerly, State Operated School System) was divided into

21 Rural Educational Attendance Areas (REAA's) to operate

elementary and secondary schools in rural regions.

The Northwest Arctic School

District is the REAA which encompasses the Inupiat Eskimo lands of

the Northwest or NANA Region. The District has an eleven member

Regional School Board which is elected at large by the people of

the region and establishes district-wide educational policy. Each

of the eleven village schools in the District has a Community

School Committee which governs local school affairs.

In its first year of operation,

the Northwest Arctic School District brought the two remaining

Bureau of Indian Affairs schools into the District and began

establishing secondary school programs in the villages of the

region. The School District now offers high school education in

all of the villages and education is governed by elected

representatives of the people.

The fortuitous chain of events

which has brought local political and economic, and now

educational control to rural Alaska has done much to eliminate the

dissonance between school and community in the Northwest Arctic.

Where school policy is made by the parents of the school children

a community commitment to education develops. When imposed from

outside, what might have been the same prescription has failed

repeatedly.

Thus, one antecedent to the

reduction of linguistic and cultural barriers in rural school

programs is the recognition that language and culture are but two

of a number of social forees affecting the lives of rural arctic

people. Researchers in culture and education have long been aware

of the systematic disenfranchisement of minority cultural ways in

the educational system of the United States Among all minority

groups, Native Americans have fared the least well in the

traditional educational system, and the Northwest Arctic has been

no exception.

Today, the most distinguishing

feature of life in the Northwest Arctic is not language, culture,

politics or economics, per se, but a combination of all of these

in rapid change. Inupiat people exhibit as many and varied

lifestyles as do people anywhere in America, from completely

traditional to thoroughly modem. In times of rapid change, the

extent to which a group of people can gain control over the

political and economic forces in their lives is the extent to

which the educational system can be adapted to meet their changing

linguistic and cultural needs.

Approach to

Curriculum

In recognition of the

blatant disenfranchisement of Inupiat people under previous school

administrations, the Northwest Arctic School District has been

pursuing a community-based curriculum development process. This

process necessitates a reversal of the former assimilative role of

the schools, making them reflective of the changing social

structure, allowing latitude for diversity of cultural values in

the school curriculum, and, in the case of the Northwest Arctic,

fostering a revival of the Inupiaq language.

A community based curriculum

development process is a whole-system process. This requires a

three faceted approach to curriculum development in which staff

development, community development and program development are all

included in the process. Most educators treat only the school

program (plans, textbooks, learning experiences) in attempting to

solve curriculum problems. In the Northwest Arctic, we assume that

no curricular change can actually take place unless the community

wants it and supports it, and unless the staff has the necessary

motivation and expertise. The diagram below depicts the

relationship between staff, program and community development in

the curriculum development process of the Northwest Arctic School

District.

The Relationship Between

Staff, Program and Community Development

|

Improving

attitudes and communication

Improving

instructional techniques

|

|

Expanding

educational opportunities

Improving

instructional resources

|

Defining

educational goals

Supporting

instructional program

At the same time, the

Northwest Arctic School District has not adopted the

bilingual/bicultural approach to curriculum development, because

of the static view of culture embodied in the approach, and

because the district's students are not bilingual, but rather are

becoming bilingual. In the past, bilingual/bicultural distinctions

have served to aggravate the students' feeling of anomie by

presenting them with the ludicrous choice of becoming a "real

Eskimo such as their grandparents were, or becoming a "white man",

neither of which was available to them in reality. The Northwest

Arctic School District takes the view that there are not two

separate societies (as implied by the bilingual/bicultural

approach), but rather that there is a viable modem-day Inupiat

culture and language which has been ignored in the school

curriculum. Thus, the district is attempting to develop an

integrated curriculum based on the individual and combined needs

of Inupiat students in a rapidly changing social and economic

structure. In this integrated curriculum, Inupiat language and

culture will not be treated separately, but incorporated through

the whole school program, and reflected in staffing patterns and

community relations as well.

The integrated approach to

curriculum development, then, is characterized by a process of

defining the schooling situation as it is seen from the point of

view of the people of the Northwest Arctic, rather than as defined

by educators and officials elsewhere.

To operationalize this process of

curriculum development based on individual and combined student

needs, the District has initiated a number of concurrent

activities to promote program development, staff development and

community development, with the aim of instituting an integrated

and excellent curriculum in the schools, a curriculum which has

the necessary support of the community and to which can be brought

the professional expertise necessary for success.

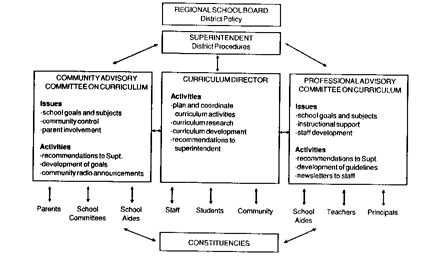

The district maintains two

advisory committees on curriculum and employs a curriculum

director, who coordinates the curriculum development function in

the district. One advisory committee is made up of professional

school staff members (teachers, principals and aides), and the

other is made up of community members (parents, community school

committee members, and school aides). Each advisory group has its

own unique perspective on curriculum development in the district

and different roles have emerged for each group, as shown on the

following diagram.

click on image for a

bigger view

As issues in district-wide

curriculum development surface, their implications for program,

staff and community development are explored. Staff and community

involvement in planning for program changes are elicited through

the advisory committees, as well as through informal and other

organizational networks. Communications are a key to effective

integrated curriculum development, with a constant two-way flow of

information between school staff and community. It is also

important to allow curriculum issues, and thus the curriculum, to

emerge from the community and its needs rather than to be

prescribed by outsiders. Thus, the emerging roles of the community

vis a' vis the school staff in the curriculum development process

are those of goal setting versus implementing education to reach

those goals.

Such a curriculum development

process is time consuming, but ensures the involvement of all

groups who have a vested interest in the education of children in

the Northwest Arctic. The district has held community meetings and

in-service training at each community school for the purpose of

identifying needs for curriculum development. Many schools have

begun the development of a sequenced program of studies which will

result in a planned school curriculum. The superintendent has

reorganized the district office program staff in order to provide

more direct services to students and schools based on identified

needs rather than traditional school roles. Principals have been

assigned to most village schools in order to provide more direct

on-site educational leadership and ensure continuity of program

for students.

As a reward for patience in this

time-consuming community-based curriculum development process, the

district now has a simple statement of goals, on which there is

wide agreement and commitment. The statement was developed and

approved unanimously by the two advisory committees on curriculum.

It reads as follows:

GOALS OF THE NORTHWEST ARCTIC

SCHOOL DISTRICT

The Northwest Arctic Region

is in a process of rapid economic, political and social change.

The main concerns for schools in this region are:

- Educating children for the

many and changing lifestyles they will lead, whether in the

village or in the city.

- Developing leadership in

every aspect of community life.

- Promoting better

cross-cultural understanding and Iñuguliq

kamaksriigalikun ("growing up with respect").

The Northwest Arctic School

District will strive toward the following goals for

students:

- Students will become

proficient in the basic skills required for educational and

societal success.

- Students will acquire

introductory skills and experience in one or more adult-life

roles.

- Students will develop

respect for their cultural heritage and an understanding of

themselves as individuals.

The Northwest Arctic School

District has the following goals for schools:

- Schools will involve the

community in educational planning, instruction, and

evaluation.

- Schools will encourage

community residents to become professional

educators.

- Schools will encourage

teachers to enhance their professional qualifications and

instructional expertise.

- Schools will encourage

students to take pride in the quality of their work and

their personal accomplishments.

These goals were developed through

a combined effort of parents, community leaders, and educators.

They represent the dreams of the parents for their children as

well as a philosophy for educators in the region.

What remains to be done in coming

years includes the development of curriculum and evaluation

guidelines for reaching these goals. The total district plan of

service will probably be built on the foundation of combined

individual student program plans as well as a flexible

district-wide system of learning opportunities accessible to all

students. The age-old rural school problems of high teacher

turnover and small school size should diminish in importance as a

continuous district-wide program of services based on student

needs is implemented.

The Integrated Approach: An

Example

The most devastating

curriculum problem in the Northwest Arctic School District at this

time is not language barriers, or cultural differences, or high

teacher turnover, or any of the other myriad of issues which come

up in discussions of rural cross-cultural education. The

singularly most critical problem now existing in this district,

and probably in most rural cross-cultural school systems in the

arctic, is a "failure syndrome" typified by a downward cycle of

teacher expectations, student motivation and student

achievement.

The interrelatedness of these

factors is one of the few established relationships in education.

For all practical purposes, it makes no difference which of these

factors may be causative. In fact, the considerable amount of time

spent in trying to place blame on one or another aspect of the

school/community is wasted, and probably contributes to the

downward spiral. The simple fact is that our students are

suffering as a result of this "failure syndrome."

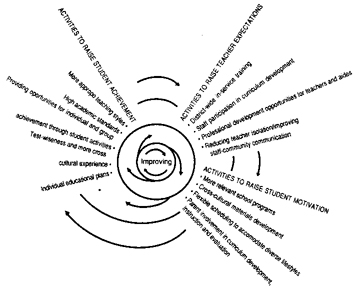

Based on assumptions derived from

educational and organizational research, and on the expressed

wishes of the people, the Northwest Arctic School District is

initiating a coordinated plan of activities designed to address

all of these problematic factors at the same time. The idea is

that no matter how this downward spiral got started, each of the

factors has become problematic and all must be turned around in

order to stop the downward spiral. Further, it is assumed that an

improvement in any one of the factors will contribute to an

improvement in the others. This is the system-wide approach to

curriculum improvement in action. Shown in the following diagram

are the activities that the district is pursuing as remedies in

each of the needed areas of improvement.

click on image for a

bigger view

Elements of program, staff

and community development can all be seen in the activities

designed to remedy the "failure syndrome" in the Northwest Arctic

Schools. If, as the district hopes, the downward spiral of the

"failure syndrome" can be stopped and turned into an upward

spiral, or a "winning syndrome," then the resolution of other

curricular problems will be simplified. When confronted in a

positive atmosphere with a winning spirit, problems oftentimes

find their own solutions.

An apriori assumption of an

integrated curriculum is its basis in the real needs of real

children. Not by legal requirement or court order, but at the

insistence of the community through their local school board, the

Northwest Arctic School District is already moving toward a total

plan of educational services based on the cultural, linguistic,

academic, vocational, and special needs of students. As a result,

in future years, the district hopes to find itself out ahead of

the field in bilingual and cross-cultural curriculum

development.

GUIDELINES FOR DEVELOPING AN

INTEGRATED BILINGUAL AND CROSS-CULTURAL CURRICULUM

To whatever extent the

experience of the Northwest Arctic School District can be of value

in other rural or cross-cultural situations, a summary of the

critical points in the district's curriculum development process

is offered here. These points are raised in the form of

organizational patterns which have evolved in the school district,

and which seem to contribute to a successful curriculum

development effort.

Attend to the Changing Nature of

Society

To a great extent in the

past, schools have had "cultural blind spots" where students are

concerned. Under the guise of treating all students equally,

minority cultural ways have either been absent or highly

stereotyped in the school curriculum.

Local control of education in

rural Alaska has done much to counter the "cultural blind spots," and allow

the present-day (not the stereotyped) needs and desires of the people to emerge.

Necessary in establishing local control

of schools are educational leaders who can enter a cross-cultural

situation with an open mind, allowing people to be who they are

and become what they will.

Treat the Whole

Curriculum

In an adequately integrated

bilingual and cross-cultural curriculum, the school should reflect

the community in every aspect, not just in revised text materials

or special ethnic studies programs. Staff readiness, community

support, and student motivation are keys to any successful

curriculum, regardless of language or culture. Since the Northwest

Arctic is an Iñupiat region, the schools should be

Iñupiat institutions.

A wide vision of what schools do

and can do, attention to the real needs of real children (not

stereotyped children), and a positive attitude, can further the

development on an integrated bilingual and cross-cultural

curriculum.

Be Honest

Centuries of wrongs cannot

be righted overnight. But one of the purposes of working to

develop a cross-cultural curriculum is to resolve the

contradictions, or bridge the gap, between what is said and what

is done.

Open channels through which people

can be heard are vital to planning as well as to developing

community support for school programs. In the case of the

Northwest Arctic, the two curriculum advisory committees as well

as a number of informal channels are open. Again, regardless of

language or culture, people everywhere want to be treated with

respect. When the Community Advisory Committee on Curriculum was

asked to decide on a name for the district curriculum, they chose

Iñuguliq kamaksriigalikun, which means in English, "growing

up with respect." Iñuguliq kamaksriigalikun has become the

theme of the district's curriculum development efforts.

Being honest means stating things

such that others can understand, weigh the consequences, and

render their own judgments. The curricular implication is that

policies, procedures, guidelines and such should be stated simply

and clearly, and time must be taken to explain new

ideas.

Being honest means not advertising

things that cannot be delivered. In the past, people in rural

cross-cultural schools have been promised much more than they ever

got. The Northwest Arctic School District is attempting to focus

its effort on a small number of clear and attainable educational

goals, which are identified as the most pressing by the people

themselves.

Be United

The only truly bilingual and

cross-cultural curriculum is one in which educators and community

are united in their view of what the schools are doing. Patience

and compromise are keys to developing cross-cultural unity.

Once wide agreement has been

reached on important curricular issues, the combined school staff

and school community will be unbeatable in finding solutions to

curricular problems. In a like manner, when staff and community

stand strong together with a clarity of purpose, interference from

outside the district can be minimized.

A Final Note

So the curriculum developers

in a bilingual cross-cultural situation need to practice the art

of listening; keep an open mind about the curricular imperatives

of language and culture; operationalize the expressed desires of

the people in the form of a clear, continuous, simply stated,

easily understood and workable curriculum; translate and negotiate

the important curricular issues among the different interest

groups; and be ready to learn much more than expected.

The curriculum in the Northwest

Arctic School District is being (and probably should be) developed "from scratch" because

of the unique political, economic, social and cultural changes taking place

in the region. As can be

inferred from this paper, the emphasis is on process and

involvement, with a determination to make the products conform

with the expressed needs of the people. Programs for staff

development, including encouraging Iflupiat teacher-trainees, are

being initiated on a district-wide basis. Program planning and

fiscal planning are being coordinated in order to unify the

diverse district programs toward the end of meeting all students'

needs.

All of these processes are woven with the threads

of staff development, program development, and community development, on

the loom of lñuguliq kamaksriigalikun. Time will tell if the Northwest

Arctic has chosen the right path.

Foreword

J. Kelly Tonsmiere

Introduction

Ray Barnhardt

Section

I

Some Thoughts on Village

Schooling

"Appropriate

Schools in Rural Alaska"

Todd Bergman, New Stuyahok

"Learning

Through Experience"

Judy Hoeldt, Kaltag

"The

Medium Is The Message For Village

Schools"

Steve Byrd, Wainwright

"Multiple

Intelligences: A Community Learning

Campaign"

Raymond Stein, Sitka

"Obstacles

To A Community-Based Curriculum"

Jim Vait, Eek

"Building

the Dream House"

Mary Moses-Marks, McGrath

"Community

Participation in Rural Education"

George Olana, Shishmaref

"Secondary

Education in Rural Alaska"

Pennee Reinhart, Kiana

"Reflections

on Teaching in the Kuskokwim Delta"

Christine Anderson, Kasigluk

"Some

Thoughts on Curriculum"

Marilyn Harmon, Kotzebue

Section

II

Some Suggestions for the

Curriculum

"Rabbit

Snaring and Language Arts"

Judy Hoeldt, Kaltag

"A Senior

Research Project for Rural High Schools"

Dave Ringle, St. Mary's

"Curriculum

Projects for the Pacific Region,"

Roberta Hogue Davis, College

"Resources

for Exploring Japan's Cultural Heritage"

Raymond Stein, Sitka

"Alaskans

Experience Japanese Culture Through

Music"

Rosemary Branham, Kenai

Section

III

Some Alternative

Perspectives

"The

Axe Handle Academy: A Proposal for a Bioregional, Thematic

Humanities Education"

Ron and Suzanne Scollon

"Culture,

Community and the Curriculum"

Ray Barnhardt

"The

Development of an Integrated Bilingual and Cross-Cultural

Curriculum in an Arctic School District"

Helen Roberts

"Weaving

Curriculum Webs: The Structure of Nonlinear

Curriculum"

Rebecca Corwin, George E. Hem and Diane Levin

Artists'

Credits

|