|

Lessons Taught, Lessons Learned Vol. I

WEAVING CURRICULUM WEBS:

THE STRUCTURE OF

NONLINEAR CURRICULUM

by

Rebecca Corwin

George E. Hein

Diane Levin

Graduate School of

Education

Lesley College

Cambridge, Massachusetts

This article was originally

published in Childhood

Education, March,

1976.

Described in a story by Doris

Lessing is a fabulously fertile African garden, "...rich chocolate

earth studded with emerald green, frothed with the white of

cauliflowers, jeweled with the purple globes of eggplant and the

scarlet wealth of tomatoes. Around the fence grew lemons, pawpaws,

bananas-shapes of gold and yellow in their patterns of

green."* But the garden is a failure for the London woman

who planted it. It does not conform to her sense of what a proper English

garden

should be.

All of us are limited by our

background and experiences; we have difficulty in recognizing the

value of pieces of the world that are unfamiliar to us. The things

we grew up with, what we expect, are understood and appreciated;

the strange new sights-whether a garden full of exotic fruits or a

classroom full of diverse activities-present problems. No matter

how robust and vital the experience, we need to restructure our

thinking and our expectations in order to appreciate new

events.

Traditional descriptions of

curricula are tidy and tended. Usually they are linear: a lesson

consists of presenting an idea, learning about it and summing up

the relevant concepts. But a curriculum need not be familiar in

this way. Consider the following events:

One day Susan, a third-grader,

brings a spider to school and shows it to her classmates during

class meeting. The teacher and children ask many questions: Where

did she find it? How did she catch it? Has she fed it? What does

she plan to do with it? The teacher suggest the children build a

cage for the spider. What does a spider "home" need? Three

children volunteer to go to the school library to get books that

will help them learn more about spiders and how they live.

Meanwhile two children discuss getting food for the spider and two

others consider what the spider should be called. One child

recounts the experience of watching a spider spin a web. Before

the meeting ends, the teacher makes a list of the questions that

have been raised and of some suggested activities. The children

list their names beside the activity on which they plan to begin

work.

A visitor walking into this room

later in the day sees three children sitting near the spider with

a book open, trying to identify what kind of spider it is. They

are discussing its color, number of legs, eyes, body parts and

size. They get a magnifying glass to observe their spider more

carefully. On the basis of their reading, they draw several

conclusions: "This kind lives only in Africa so it can't be that."

"These are poisonous and we know ours is safe." "Ours is too big

to be that kind."

Three children get a box, cut out

one side and cover it with clear plastic to make a spider house.

They discuss how to make air holes so the spider can breathe. One

child says she has a piece of fine screening at home and offers to

bring it to school. She thinks the holes are small enough so the

spider cannot get through, but they will have to check to be sure.

Two other children return from the playground where they have

gotten a few twigs to put in the box so the spider will have a

place to build a web. After a hard search, three others have

managed to catch a few bugs to try feeding the spider. They plan

to watch to see what happens when they put the bugs in with the

spider. The teacher comes over with a homemade book and suggests

recording the results so they will know what to catch tomorrow.

One writes a title, "What Spiders Eat," on the front.

Two weeks later, when the visitor

returns, the spider's home is completed. Matted on construction

paper and carefully displayed are two poems about the web the

spider has spun. A child has "spun" a web, too, by weaving on a

circular loom and has written an account of how difficult it was

to make the weaving as well as the spider did its spinning. Other

children have made "books," which contain stories they have

written and illustrated, including one about a monster" spider.

One book tells about the kinds and quantities of food the spider

ate. A chart shows whose turn it is to find food and feed the

spider. Someone has written about the size of the web and how long

it took to be built. One group has begun collecting ants and has

made an ant farm.

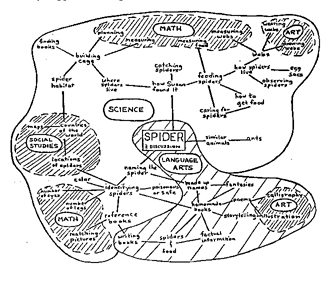

The many activities in this

classroom do not directly relate to our usual notions of

curriculum. How can we keep track of learnings that occur in such

an apparent hodge-podge? One way of recording curriculum

information is called a flow chart or flow tree

. The previously described

spider activities might appear as in Figure 1.

Figure 1

click on image for a

bigger view

A more formal, traditional

approach to a curriculum might, in contrast, present spiders as

part of a science unit in a linear way.

|

SPIDER

|

-CHARACTERISTICS OF

SPIDERS

|

-IDENTIFICATION OF

SPIDERS

|

-KINDS OF

SPIDERS

|

-CLASSIFICATION OF

ANIMALS

|

This more familiar design,

starting with an experience intended to lead to a specific goal,

represents a totally different approach to curriculum and learning

from the detailed example given above. It is helpful to contrast

and compare the two ways of organizing.

In a traditional approach to

knowledge, problems about the coverage of skills areas do not

arise seriously in any theoretical way. The teacher, or curriculum

developer, decides what subjects or concepts the class or group is

to cover and then arranges the information in what is considered

the most appropriate sequence. The experiences illustrate the

concepts but do not determine the curriculum.

Informal or "open education" approaches consider the acquisition of skills

quite differently. Because there is no predetermined order to and coverage

of

material, it is often assumed incorrectly that informal education

advocates have no concern for skills. Such unstructured classrooms

might be a joy for lazy teachers, but they certainly do not

reflect a real sense of open education. Teachers who support open

education would argue that there are indeed skills they want to

impart: they acknowledge the importance of children's learning to

read, to compute and to understand the world. But they believe

that because individual children learn in a variety of ways, with

different children learning different things from the same

experience, a new classroom organization and a less linear

curriculum are required.

When a teacher surrenders the

support of the predetermined structure of knowledge, as reflected

in a formal curriculum, he or she takes on the difficult job of

developing an overall structure in which children's individual

paths can flourish through learning activities. Curriculum

trees or flow charts are not just nice decorations or a rationale

for lack of structure. They are an alternative way of organizing

experiences of the world and provide both a guide and a challenge

for the teacher.

If we accept the idea that

children have individual learning styles and that they go through

horizontal and nonlinear growth periods of different intensity and

duration, then we must also accept the view that we cannot cut up

the day in neat segments and decide what will be learned in each.

We need to encourage and facilitate individual children's

development. We also need to think about the class as a group and

what its needs are, providing for both small- and whole-group

activities.

In this new kind of structure,

then, Sarah and Johnny are not asked to engage in the same

activity minute by minute. Instead, their leamings over periods of

weeks and months are the central concern. An open education

teacher does not see knowledge as cut up into little bits but does

have long-term goals and clear ideas about the child's need to

learn through interaction with the world. The teacher can explain

the learning taking place during different activities by

references to examples of a specific child's work and can also

document the learning that has gone on over a period of

time.

Interactions with the real world

through materials, rather than mediated time chunks, tend

therefore to determine curriculum in informal classrooms. This

quite radical ("back to roots") idea is, indeed, a restructuring

of curricular organization that is different from the "usual." The

affluence of the late sixties encouraged many school systems to

invest heavily in materials and games, and many classrooms are now

equipped with a variety of attractive materials. These materials

usually are used only as a supplement to the traditional program,

however, rather than as a potentially vital experience in

themselves. Often they are employed to entertain the children

while the teacher works with one or another group. A philosophical

shift is needed. When a teacher better understands the central

position of materials in learning and the non-linear nature of

learning, then he or she can act on that understanding by becoming

familiar with materials and by working with the children through

them.

The teacher's role is crucial in

structuring the nonlinear curriculum. It involves the ability to

respond to children's interests as they arise and to respect their

seriousness of purpose by providing for extensions of the

immediate learning situation. The teacher in the example of the

spider asked specific questions in order to promote discussion

skills, provided a framework of plans and activities for children

to follow, and helped children decide what they wanted to learn

and how to go about it, providing books and materials as needed.

She couldn't plan everything in advance but instead supported

children's interests and skills, making educated guesses about

what would most likely spark children's imagination.

What are the implications of

this type of teacher role? What underlies the teacher's image of

his or her job? To sum up, such a teacher believes that children

learn best:

- Through their individual

interests and strengths.

- Through active, concrete

experiences with materials and ideas.

- By interdisciplinary synthesis

of usual subject areas; not all learning can be broken into

boxes or into sequences.

- By experimentation-watching,

trying, adjusting, exploring ideas until they "jell."

- Via a wide range of horizontal

experiences (those that are at the same competency

level). Repetitive though such experiences may seem, once is

often not enough for mastery. At the same time, however, the

teacher provides vertical

experiences that may move the child onward in terms of

competency level. A balance of these components is

sought.

These notions of the teacher's role

and their relation to views about children's learning are different

from the traditional structure of schools and curriculum. But, like

the succulent fruit of the African garden, they represent the product

of another tradition; they come from a long history of observing

children in action in the real world.

Despite recent talk about "backlash" against open education, thoughtful implementation

of informal

approaches is beginning to occur throughout the United States and

Canada. A number of schools are developing classrooms where slow,

steady examination of curriculum decisions is leading to curriculum

changes for children. To establish a successful classroom of this

kind takes a lot of hard work and also confidence that a different

view of curriculum and knowledge can help children to grow and learn.

To alter curricula is not enough: rather, the entire view of what

things might constitute appropriate support for the nonlinear

curriculum must be adjusted-as happened when a spider went to

school.

*From African

Stories by Doris Lessing.

Foreword

J. Kelly Tonsmiere

Introduction

Ray Barnhardt

Section

I

Some Thoughts on Village

Schooling

"Appropriate

Schools in Rural Alaska"

Todd Bergman, New Stuyahok

"Learning

Through Experience"

Judy Hoeldt, Kaltag

"The

Medium Is The Message For Village

Schools"

Steve Byrd, Wainwright

"Multiple

Intelligences: A Community Learning

Campaign"

Raymond Stein, Sitka

"Obstacles

To A Community-Based Curriculum"

Jim Vait, Eek

"Building

the Dream House"

Mary Moses-Marks, McGrath

"Community

Participation in Rural Education"

George Olana, Shishmaref

"Secondary

Education in Rural Alaska"

Pennee Reinhart, Kiana

"Reflections

on Teaching in the Kuskokwim Delta"

Christine Anderson, Kasigluk

"Some

Thoughts on Curriculum"

Marilyn Harmon, Kotzebue

Section

II

Some Suggestions for the

Curriculum

"Rabbit

Snaring and Language Arts"

Judy Hoeldt, Kaltag

"A Senior

Research Project for Rural High Schools"

Dave Ringle, St. Mary's

"Curriculum

Projects for the Pacific Region,"

Roberta Hogue Davis, College

"Resources

for Exploring Japan's Cultural Heritage"

Raymond Stein, Sitka

"Alaskans

Experience Japanese Culture Through

Music"

Rosemary Branham, Kenai

Section

III

Some Alternative

Perspectives

"The

Axe Handle Academy: A Proposal for a Bioregional, Thematic

Humanities Education"

Ron and Suzanne Scollon

"Culture,

Community and the Curriculum"

Ray Barnhardt

"The

Development of an Integrated Bilingual and Cross-Cultural

Curriculum in an Arctic School District"

Helen Roberts

"Weaving

Curriculum Webs: The Structure of Nonlinear

Curriculum"

Rebecca Corwin, George E. Hem and Diane Levin

Artists'

Credits

|